Artículo Stockhausen

-

Upload

sofia-infante-souto -

Category

Documents

-

view

24 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Artículo Stockhausen

-

88 Computer Music Journal

[Editors note: Selected reviews are posted on the Web. In some cases, they are either unpublished in the Journal itself or published in an ab-breviated form in the Journal. Visit www.mitpressjournals.org / loi / comj and, under Inside the Journal at the left, click on CMJs Web site. Then click on Reviews at the top.]

Events

Karlheinz Stockhausen: Cosmic Pulses

German premiere: 13 July 2007, Stockhausen Courses 2007, Krten, Germany.

Reviewed by Nick CollinsBrighton, Sussex, UK

[Editors Note: Karlheinz Stock-hausen passed away on December 5th, 2007. What this means for the future of the summer school itself is uncer-tain; but this review stands as a testament to undiminished critical interest in his work and life.]

The 10th Stockhausen Courses took place in the gentle setting of the town of Krten, near Cologne, Germany, 715 July 2007. Approximately 130 instrumentalists, musicologists, and composers attended to pay homage to the living legend Karlheinz Stock-hausen, to study with his clique of approved interpreters, to get access to the archives of his work, and simply to listen and bask. The ten- day festi-val was tightly organized, held on the grounds of a local school, whose acoustically impressive gymnasium housed each nights concerts. A typical day might involve early morn-ing gesture classes, an open rehearsal for that evenings concert, a musico-

1974) for orchestra and mimes was conducted with a tape substituting for the orchestra. Perhaps most interesting to the electronic music community, though, were the many solo tape works presented, with all lights off but for a single spotlight high up. As Mr. Stockhausen ex-plained, he had received so many comments from people uncomfort-able with total darkness that he provided the moon, but he preferred that listeners close their eyes and occasionally move their heads to track spatial movement and scene.

He diffused (or sound- projected, as he termed it) over a rig of two layers of loudspeakers, adaptable to the eight- speaker cube of Oktophonie (19901991, 69 min) or the eight- track spatial projection of Choirs of Monday (1987, 69 min) and Mittwochs- Abschied (1996, 44 min). These large- scale works, extracted from acts of the Licht opera cycle, presented listeners with an exhilarat-ing and draining acousmatic listening experience. The Choirs work is founded on recorded massed voices, spatialized in the auditorium, but the other two large- scale compositions use stock synthesized sounds. At various points during the week, especially with the presentation of works for tape and performer such as Komet (19941999) for percussion, the timbral presetsuncritically selected from commercial synthesiz-ersunderlying much of Mr. Stock-hausens output since the 1980s were apparent. A current of the primacy of pitch and space often overrides tim-bral adventure, intricate processing, and even time structures, in a way that can be disappointing to those more familiar with the fresh and invigorating sound worlds of Mr. Stockhausens great works of the 1950s and 1960s. This contrast was made evident by the performances of Gesang der Jnglinge (19551956) at

logical lecture from Richard Toop, interpreters classes in the afternoon with the faculty, an analysis lecture from Mr. Stockhausen himself, a bratwurst and beer in the local bikers bistro, the evening concert itself, and post- concert drinks and ice cream in an Italian restaurant up a hill in the plaza next to Krtens town church.

Mr. Stockhausen himself was at the time a sprightly 78- year- old (he turned 79 on 22 August, a month or so after the end of the summer courses); his 80th birthday year would have been 2008. He was undiminished by age in his energies for composi-tion, rehearsal, and self- promotion; his habits of hard work and an innate sense of purpose seem to have kept him eternally young and even fi ery (or I hesitate to think how much of a dynamo he was as a younger man; I prefer to imagine the magnetic accumulation of years of experience). The course participants seemed to bask in the glow of a living legend, occasionally a little too uncritically. Indeed, access to Mr. Stockhausen was controlled by careful scheduling of the weeks events.

At the concerts, instrumental works were interleaved with tape pieces (run from a Tascam DA- 88 digital eight- track unit), which seemed to hold equal status. Mr. Stockhausen sat at the mixing con-sole in the center of the audience for every concert, regulating the micro-phones he uses as a standard to amplify all acoustic instrumentalists and make their every whisper audible to the back row. There was a bias toward works from the 1970s on, including multiple arrangements of works for solo performer, as most readily provided by the expert inter-preters on hand, and naturally con-tinued at the three student concerts deriving from the interpretation classes. Lacking any larger ensem-bles, the performance of Inori (1973

Reviews

-

Reviews 89

from low to high frequency and corresponding slow to fast rotation on the spatial paths, entering one by one from the (s)lowest and leaving in reverse. In the central portion of the 32- min work, all layers are present, and the density of information pro-vides the aforementioned challenge. In psychological terms, it is challeng-ing with anything more than four layers at once, and the overall sum-mation of layers can become the aggregate impression, with attention fl ickering between layers as they are emphasized and perturbed following complex charts of parameter enve-lopes. The source timbre for indi-vidual lines is a rather cheap electric piano sound, which is quickly sub-sumed into the granular storm as the layers gather and tempi increase.

not made up his mind concerning it. The reaction at the world premiere in Italy had seen him signing autographs for one and a half hours after an enthusiastic response from a younger crowd. The work had been commis-sioned for the Dissonanze Electronic Music Festival, an event mainly focused on electronica.

Cosmic Pulses (2007) is arranged for eight tracks, with 241 different trajectories in space (program notes). The work utilizes 24 layers of sound, each with its own associated central pitch, tempo, and spatial motions, each enlivened by manual regula-tion of the accelerandi and ritardandi around the respective tempo, and by quite narrow glissandi upwards and downwards around the original melo-dies (ibid). The layers are ordered

the opening address, and Kontakte (19581960, in the version for percus-sion, piano, and tape) played by stu-dent performers on the last day. Although some splendors were found in the long Licht pieces, they lacked uniform quality; there were also coarse edges in studio production, from poor layering and fades to awk-ward transitions.

A great deal of excitement, how-ever, had grown around one particu-lar new work, Cosmic Pulses, which received its German premiere at the Friday night concert on 13 July. Originally unveiled in Rome not long before, on 7 May 2007, Mr. Stock-hausen had warned the participants earlier in the week that this work would provide a challenge to the listener, and that he himself had still

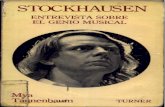

Production in March 2007 of Cosmic Pulses at the White House of the Stockhausen Foundation; from left to right: Joachim Haas and Gregorio Kar-man, collaborators of the Experimentalstudio fr

akustische Kunste e.V., Freiburg, behind them Antonio Prez Abelln, and at the right Karlheinz Stockhausen. Photo: Kathinka Pasveer.

-

90 Computer Music Journal

hear the spatialized version, and one would hope that any future Stockhausen- Verlag release would be in a multi- channel format; played 10 decibels louder, Cosmic Pulses could even make a terrifi c entrant into the spatial noise scene!

Discussing the work in the semi-nar session on the following day, and also bringing in general comments made during the week, Mr. Stock-hausen admitted that the work might be viewed as not music, just sound, and that it might be best to just take it as a natural phenomena and not think of composition. It is hard to tell how disingenuous he is concern-ing infl uences; rumor would have it that he listens to little or no contem-porary music (especially not electroa-coustic, and I would imagine no Merzbow), and so the noise- music aspects of Cosmic Pulses are not fully appreciated by him. Concerning new electronic music made by the current generation, he spoke rather disparag-ingly of just scratching, old radios, any kind of so called electronic device for making noise, and also added that I detest everything now based on sampling. His lifework has been motivated by seeking variety, though it is hard to support his claim that I have no style, I dont want a style, and the full implications of his assertion against people who are the result of habits or fashion . . . my music is not! Mr. Stockhausen him-self caricatured his critics: most colleague composers will say that old Stockhausen is still a serialist com-poser. And yet, he is one who ad-mits serial composition is not easy to listen to, and has a lifetime of experience in the practical and psy-chological compromises of effective musical work.

When I went up after the Cosmic Pulses performance to congratulate him, and to mention I would be reviewing the concert for CMJ, Mr.

throes? Bass keeps recurring, not loud enough! Fader riding, bigger gliss near end, modula-tion slowing, running cosmic patches, Siriusly exhausting, a few roars near the end, pitter patter of spatial space electron-ics, drove someone away [an audience member leaves at this point], one layer becomes domi-nant then falls back, slowing to fewer layers, more controlled gurglings, selective, relaxing into less layers, closing down, suddenly gentle, cathartic, re-turning to sanity, makes sense, sudden awkward end . . .

After the work fi nished, the longest applause of the conference was heard; Mr. Stockhausen received a partial standing ovation (and also a yell of derision and a few boos). Cosmic Pulses certainly stirred up the audience!

In the post- mortem discussions among attendees, the consensus seemed to be of a thrilling ride, but of the overload lasting too long in the middle; those who had heard more recent electroacoustic music were slightly perturbed by the bad timbre at the start for the source sound. In defense of the length, it might be a necessary compositional device to offset the beauty of the closedown, when normal information processing levels are re- entered. The whole piece offers an alternative listening experi-ence where there is no chance to follow all events. It might cautiously be claimed that Mr. Stockhausen achieved a controversial success, and created a work that has reinvigorated his electronic music. For the reader immediately curious about the sound, the YouTube video from Dissonanze seems unfortunately to have been taken down at the time of writing. If there are public perfor-mances coming up, it is essential to

As I listened to the work, I noted a tumult of impressions in real time, writing maniacally in the dark, a number of which I now list in the order of their original writing. They give, I hope, some idea of the speed with which the complexity builds, and the impressions of being caught in a maelstrom:

. . . violent spasms of space, serial recurrences, a Copernican asylum, over- literal crashes, rushing more and more beyond sense, like being inside Stock-hausens mind as he composes, a battle of enraged keyboardists in a tempo war, granular roars, bass pedals and clatters, gurgling granules accelerate, pushing the boundary of information, tapes spooling mercilessly, a labyrinth of tone pulses, a multiplicity of collisions in an organ factory, even poor synthesis cant ruin this controlled chaos, wider and wider dynamics and layering, building to the synchronies of planets, raging layers, raging presets in a keyboard shop war, a fi ght at an audio convention, the natural conclusion of serial overload / overlord, the end of bathtime in the lair of the space emperor, spending uncomfort-ably long in the synth dungeon, dribbling on an electroacoustic conference from above, layers rage and sear in unadulterated pleasure, higher layers reveal then a return to more chaos. Staggering down, staggering up, push push push!!! Underground serial movement, new serialism in the court of king computer music, a tumultuous tempest of temperamental tantrums, only Stockhausen could demand such literal length, either terrible or extremely good depending on your mood, entering the fi nal

-

Reviews 91

Having attended the last few ICMC gatherings, I realized that there was no way I could attend all the concerts, listen to the paper presentations that interested me, as well as present my own two papers, and leave the event with any coher-ent memory. As such, I made a rather bold decision to only attend the concerts that presented live electron-ics, my specifi c interest. I realize that I missed some great music; however, in order to do justice to those works I did hear, I felt this was necessary.

A local club, Huset, hosted the late night concerts. For several years now, ICMC has presented an alternative venue for music events, sometimes called off- ICMC, in which music closer to club culture (rather than the concert hall) has been presented. Performers interested in improvisa-tion, loops, clear pulses, and longer time frames have had an opportunity to present their music in a more informal setting. Unfortunately, many delegates do not attend these events, most often due to their late hours (usually 10 or 11 p.m.) rather than considerations of musical aesthetics. Due to a wicked case of jet lag, I was able to attend, and, perhaps more importantly, appreci-ate, most of these late- night events.

A curious decision was made at ICMC 2007, perhaps inadvertently, to place almost all works that involved live electronics onto late night concerts. The result was up to three concerts per night (10 p.m., 11 p.m., and midnight) occurring each night, sometimes with three or four works per hour. (I remember the days when a single live electroacoustic show took all afternoon to set up, and only rarely succeeded on a technical level, whereas these concerts all came off smoothly. Kudos not only to the technical staff, but also to the composers and performers who had the nerve to set up in under 10 min-

Music Association and Aalborg University Esbjerg, the International Computer Music Conference (ICMC) 2007 took place 2731 August in the picturesque Danish city of Copenha-gen. Organizing chairs Kristoffer Jensen, Lars Graugaard (music), and Stefania Serafi n (papers) did an admirable job of bringing together researchers and composers and presenting a very successful event.

Rather than having all events hosted at a single location, the entire conference was spread throughout the city, with paper sessions and a daytime concert at the Danish School of Architecture, afternoon concerts at various locations in the town center, and late night concerts in a local club. Although this certainly pre-sented unique listening experiences in the various venues, it also pre-sented some logistical complications. For example, the installations, only active during the daytime, were located at the same venue as the late night concerts, several kilometers from the paper sessions; therefore, one had to make the decision to leave the paper sessions for at least an hour in order to view any of the installations.

As is usual for ICMC, there were several concerts spread throughout the day. Perhaps more unusual was the clear division in theme be-tween them. The daytime concerts took place at the same location as the paper sessions, and were limited to eight- channel fi xed media works. The late- afternoon concerts alter-nated between the PLEX music theater, in which mixed chamber works with and without live elec-tronics were presented, and the DGI- Byen, a conference center whose swimming pool area hosted several water concerts. The impressive Black Diamond concert hall hosted the larger ensemble works, and video works were performed at the Tycho Brahe Planetarium.

Stockhausen animatedly exclaimed Aha, I will tell you how to review it! I havent followed his instructions, but its good to know that he still cared so deeply about rules. It was probably a joke, his personal assis-tant, Sabine Schulz, informed me.

Information on the annual Stockhausen Courses is available from the Stockhausen Web site (www.stockhausen.org / ). The courses pro-vide an outlet for, and festival of, Pro-fessor Stockhausens music in his home town, and although the rela-tively closed clique of family and performers, and the reverent atmo-sphere and exclusion of any other composer, might be wearing to some, the overall benefi t is a period of unin-terrupted study of his output. Per-formers have the chance of lessons with the faculty members (this year primarily covering voice, percussion, piano, fl ute, clarinet, and trumpet, though other instruments can be sup-ported through alternative versions of some scores), and there are prizes for those selected to perform in par-ticipants concerts, and a new prize for the best musicological contribu-tion in the previous year. There are, however, currently no conference sessions or composition lessons as such. There is only one composer at the Stockhausen Courses.

International Computer Music Conference 2007: Live Electronics

Re:NewForum for Digital Arts, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2731 August 2007.

Reviewed by Arne EigenfeldtVancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Presented as a joint initiative be-tween the International Computer

-

92 Computer Music Journal

included the composer on an eight- string fi ddle, the works bright har-monies and continual pulse were refl ective of the works Scandinavian fi ddle- band originsfi tting, consider-ing the location of the festival itself.

Tommaso Peregos Incastro di Mondo featured the composer on a wireless gamepad controller, facing the musiciansfl ute, bass clarinet, and violinand thereby giving the impression of playing them. The extreme digital processing of the mu-sicians sound was nearly continual, enforcing the post- postmodern noise aesthetic. Unlike many of the works in the festival, the work was shorter than it needed to be.

Most of the music featured at the Black Diamond concert hall was for large ensembles and fi xed media, although two works incorporated live computers. Joshua Parmenters Organon Sostenuto, for fl ute, bassoon, cello, contrabass, and interactive electronics, deserves mention, not only for its use of live computer processing, but for the sophistication of the composition itself. The computer provided a harmonic and textural web derived from the live performers; however, the resulting relationships were much more than a simple delay line. The responses were more orches-tral than singular solo lines, the result of the clearly thought- out use of a live computer and its potential role. For example, the multi- channel spatialization was saved for later in the piece, an effective choice. I liked the shimmering extended chords that were often created, and I found them more effective than the one- to- one delay section (which occurred only once). Of particular note was the feeling that the computer voice was clearly an integral part of the overall composition, rather than impro-vised effect overlaid in performance.

The fi nal evening concert at the

Misra, and Perry Cook) was per-formed to an appreciative audience, and more in keeping with what I expected from one of computer musics grandfathers. This new work was one of the most effective live works of the festival. The com-poser achieved an admirable and fl uid relationship between performer and accompaniment, incorporating one- to- one relationships, but not relying upon them (as other gestures contin-ued independently). In one case, the soprano sang an extended melody, accompanied by busy high frequen-cies; the last note of the phrase triggered a low frequency tone that cut off the synthetic gestures, result-ing in a magical interaction and con-fl uence. Curiously, the FM sounds did not appear dated: the composer created a wide variety of sounds that remained unifi ed in timbre.

Sami Klemolas Fragile demon-strated one of the pitfalls of live electronics: the audience wondering what is the computer onstage do-ing? Fragile was a modernis gestural work for three strings, two winds, piano, and onstage computer in which occasional instrumental notes were amplifi ed, but not necessarily pro-cessed, through the loudspeakers. The electroacoustic elements to this piece were subtle and didnt seem integral to the work, other than the last two minutes. Is that a criticism? It is when the work is on a program entitled Ensemble Electronics.

Dan Truemans Lasso and Corral: Variations on an Ill- Formed Meter proved to be a clever work in which the four onstage computers served as audible metronomes to the four musicians (and audience). The au-dible click could possibly have been replaced with a conductor; however, it added a whimsical nature to the work, at times hiding the complexity of the music itself. Impressively performed by the quartet, which

utes in many cases.) Most of the works presented in these late- night concerts were not what I would nor-mally associate with the club atmo-sphere; many should have been presented in more formal listening events because they required active listening by an audience not dis-tracted by beer and loud conversation.

Some works that incorporated live electronics did occur in venues out-side of the club environment. The PLEX was an intimate space, but I found that the wide loudspeaker placement separated the original sound source from the signal process-ing in a rather dramatic way; this was especially evident in Robert Rowes Moon on one side, Sun on the other for harp and interactive electronics. Mr. Rowe is one of the masters of interactive computer music, and he displayed his ability in this fi ne work. Moon exhibited a great deal of interesting and unexpected pro-cessing that clearly explored a variety of relationships between harp and electronics; sometimes subtle shad-ings, at other times stark opposition. Like any good interactive work, the processing was clearly related to the live performance, without being obvious. Mr. Rowe was also able to precede gestures in the live part with prerecorded material. Because I read the program notes beforehand, I exerted some effort in trying to fi gure out what was live, what was pro-cessed, and what was soundfi le play-back; this was eventually forgotten (and unnecessary), given the quality of the piece.

John Chownings Voices, a work for soprano Maureen Chowning and interactive electronics (the program notes stated Max / MSP), caught me by surprise. Earlier in the concert, a reconstructed version (by Kevin Dahan) of Mr. Chownings classic Stria, with new visuals by the Prince-ton Sound Lab (Ge Wang, Ananya

-

Reviews 93

piece one would expect to hear. The audience seemed to recognize this, and remained relatively quiet for the performance. The work demon-strated some of the slow extended gestures of improvised music, while also providing some quick sectional changes of pre- scored compositions.

Perhaps it was Michael Youngs slight free jazz stylings on electronic piano at the start of his piano_proth-esis that suggested to the audience an informal environment that invited them to resume their conversations. For those that did, they missed a truly inspired interactive work that showed the potential of real- time neural networks in interactive music. The composers system refl ected, interacted, expanded, and developed his live improvisations on the piano in a way that was both unpredictable and musical. The complexity of interaction between human and software went well beyond the capture / manipulate / regurgitate aesthetic of much live computer improvisation; the neural network showed its usefulness through its quick adaptations to Mr. Youngs playing, recognizing situations, and seemingly anticipating them. The performance would have done well in a concert environment, rather than the noisy late- night club.

Unlike Michael Youngs work, klipp av (Nick Collins and Fredrik Olofsson) were completely at home in the club atmosphere. Beginning with a light tonal harmonic pattern and black- and- white visuals, their collaboration quickly evolved into darker textures with the entrance of percussive sounds. Mr. Olofssons live video, using a handheld video recorder, teased us with blurry two- bit images of his face (and later a rubber duck), and it seemed that we would be in for an interesting, but perhaps predictable, electronica- plus- visuals performance. Catching

Dubois and Lesley Flanigans Biolu-minescene was a work that one would expect from a late night ICMC: computer processing of a live singer with generous amounts of feedback delay, resulting in long gestures that take extended periods to evolve and change. The difference here is that the collaborators have obviously performed together, as Ms. Flanigans vocal improvisations were clearly created with full knowledge of the potential processing. Mr. Duboiss background textures, complete with the requisite low frequency drones, high frequency noises, and subtle beats constructed from timbral pro-cessing rather than more direct per-cussion sounds, were (almost) always in control: to his credit, the feedback got away from him only once.

Ajay Kapur, known for his work in robotics and sensor work, chose to leave his drum robot at home for Digital Sankirna, instead focusing upon his sitar to create a high en-ergy electroOrganic tribal experience. If that means dance music with an electroacoustic twist, he certainly succeeded. Playing his modifi ed sitar and controlling Ableton Live soft-ware, the composer used the sensing capabilities of his sitar to infl uence the live processing along with more obvious interactions with drum loops. The audience seemed to appreciate the results: on one hand a driving corporeal rhythm that suited the environment, but at the same time, careful manipulation of timbral elements that could be appreciated if one chose to listen closely.

Silvia Matheuss Crossings fea-tured Morten Carlsen on trogat (a single- reed wind instrument that resembles a wooden soprano saxo-phone) and Roberto Morales on fl ute and interactive electronics (complete with a Wii strapped to his arm). A curious piece for the venue, not the typical electronica- infl uenced noise

Black Diamond featured Calliope Tsoupakis Mal di Luna, a work for Frances- Marie Uitti on electric cello, amplifi ed chamber ensemble, and live electronics. Featuring a superstar performer on the fi nal mainstage concert raised my expectations, particularly because it was a live electronic work. This was only reinforced when Ms. Uitti appeared on a raised platform, playing her fi ve- string electric cello. The work began effectively with the solo cellos artifi cial harmonics coupled with subtle delay processing, creating a shimmering texture evocative of the title. The extended solo progressed to a dynamic divergence between shim-mering stasis and violent gestures, dramatically diffused in multiple channels. The orchestra was a colorful combination: guitar, mando-lin, harp, percussion, bass clarinet, and piano. It also included a synthe-sizer which, unfortunately, produced a number of uninteresting drones. The sound mix was at times confus-ing, as Ms. Uittis live sound occa-sionally disappeared among the amplifi ed orchestra. One section featured what appeared to be play-back of the soloists earlier material, but it was unclear why it was occur-ring at that point, as Ms. Uitti wasnt herself playing. At times, the piece seemed to forget it was electroacous-tic. When it did explore electroacous-tic elements, the occasional duets between soloist and computer were most effective when the processing remained subtle and effective, something harder to achieve within an ensemble of ten instruments. Although it was an evocative work that featured some dramatic playing by Ms. Uitti, the live electronics seemed to be trendy and, unfortu-nately, superfl uous additions.

The remaining works that I heard that incorporated live electronics were presented at Huset. R. Luke

-

94 Computer Music Journal

mance, including one section that feature voice- like chatter.

Gil Weinbergs performance was highly anticipated, allowing the audience to hear fi rsthand his unique robot performer, Halle, in Svobod, for robot, MIDI piano, and saxophone. His program notes stated that Halle was designed to listen like a human, play like a machine; perhaps the latter part was stated since Halle was playing two xylophones, not expres-sive instruments in themselves. Once one got over the fact that a robot was joining in on an improvisa-tion, it came across as a bit of a gimmick, much to my disappoint-ment. Compared to other systems that listen and respond (i.e., Michael Youngs), the fi nal musical result was less than stirring, seemingly inca-pable of subtle phrasing. Playing with a free jazz ensemble has already been done many times, albeit not by a robot; this musical decision, coupled with the choice of having Halle play xylophones, was, perhaps, not the best environment to feature Halles potential. The robot did know when to end, though.

Despite having most works that featured live electronics at ICMC 2007 ostracized to the late-night con-certs, I felt that the level of musical-ity demonstrated in the compositions had reached a maturity missing only a few years ago. Most of these works were no longer experimentalthe technology was clearly under control, and used for the benefi t of creating some exceptional musicnor were they suited to the club atmosphere: their subtlety was often lost in the ongoing chatter. As a genre, live electronics has grown up, and de-serves to be placed alongside fi xed media, chamber music, and large ensemble works on the main stages that allow for more concentrated listening.

I missed most of Thursdays events, my jet lag catching up to me; how-ever, I recovered the next evening to hear Hugi Gudmundssons Wind-bells, a work for small ensemble and interactive electronics that utilized simple delay lines (both forward and backward), which were effective in relation to the instrumental writing. The computer was an active part in the work, creating separate and unique layers, offering counterpoint and commentary. Despite the con-ductor making an announcement requesting the audience to be quiet, it did seem like dinner theater at times.

Cort Lippe chose to run the com-puter for his Music for Cello and Computer from the rear sound booth, leaving the performer alone on stage. This resulted in the audience perhaps not realizing the work was not for cello and fi xed media, but a thor-oughly integrated work for performer and live electronics. The interaction between performer and computer was well thought- out and controlled, ranging from subversive processing to pushing along predetermined soundfi les. The complexity of the processing, combined with the intricate interaction, resulted in a thoroughly mature and sophisticated piece of music.

Roberto Morales offered what at fi rst appeared to be a typical live work in Viento Sereno, improvising on fl uteusing the requisite ex-tended playing techniquesand Tibetan prayer bowls, while the software processed the audio in real time, extending, expanding, and altering his playing. The most un-usual aspect of the performance was his curious dancing, as he manipu-lated the Wii controller strapped to his arm. The sections where he didnt play fl ute proved more interesting, as the computer accompaniment was less directly related to the live perfor-

us somewhat offguard, two people strode casually onto the stage and gradually began an extended contact improvisation that demonstrated that the two were clearly acrobats as well as dancers. Although this may sound somewhat distracting from the already dense music and visuals being created, it resulted in an unbelievable confl uence of energy. Mr. Collinss breakbeats were synced to the quick video edits of the live movement, creating a synchronicity that had the audience on their feet. Beyond being hugely entertaining, it was equally satisfying artistically, and possibly my highlight of the conference.

Wednesday night at Huset, I was stuck in the back by the bar, and many of the more subtle and delicate transformations of the live instru-ment in Andreas Weixler and Se- Lien Chuangs The Colours of a Wooden Flute were lost. From what I could see and hear, it seemed like an effective combination and dialogue, in which the live processing formed an integral part of the works success. The processing had consistency, yet managed to create enough variations to prove dynamic.

Richard Dudass Prelude for Clarinet and Computer was particu-larly hampered by the venue. The work was a sophisticated composi-tion for a scored clarinet and evi-dently pre- scored live processing, in which the processing perfectly augmented the clarinet writing. It came off so seamlessly that the audience seemed to miss the techni-cal achievement of the work, one that ten years ago would have been almost groundbreaking, whereas now is considered virtually commonplace. However, the work was defi nitely not simply a study in technical matters: the musicality of the work is what I remember most.

-

Publications 95

music, SuperCollider, pure data, and many other development environ-ments freely available to anyone in-terested. It could so easily have been different.

Jean- Claude Risset, a similarly generous soul, contributes a lengthy article to this volume (as he did for the volume on John Chowning, reviewed in CMJ 30:1), placing Maxs work into historical context and outlining his own research as it has interfaced with his mentor (begin-ning with his fi rst exposure to early publications on digital synthesis and his subsequent decision to pursue research into timbre at BTL from 1964). This is a detailed accounting of chronology and research, and in fact forms the bulk of the book (30 pages of the 100 or so of the volume). I found one item especially fascinat-ing: a description of a graphic inter-face for sound synthesis implemented in 1966 on the IBM 7090 computer. Apparently, Iannis Xenakis and his

elements of the Max phenomenon is that it is still possible to bump into him at the International Computer Music Conference (he was the key-note speaker at the 2006 conference in New Orleans) or other such gather-ings. He is perhaps the most critical core of what is an increasingly di-verse and fractured computer music community. As becomes apparent in this volume, in case it wasnt already, he has supported or facilitated many of the important fi gures and institu-tion of computer music. This publi-cation tells the story, and fi lls in many details that are not covered in broader histories of the fi eld.

As with each of the other books in the Portraits Polychromes series, editor velyne Gayou presents a lengthy interview with the featured person. It should be noted that Max is the fi rst non- composer to be included in this series, again underscoring his importance to the fi eld (and some would call him a composer anyway, even while his modesty compels him to deny it). This is a wide- ranging discussion over 18 pages, covering Maxs background, his work at BTL, his research, his career, his love of music, etc. We get some insight into the open research environment at BTL, and while many of Maxs tech-nological innovations are already well known, we also gain insight into his deep generosity and willingness to collaborate (including his devotion to chamber music, which he carries on as a violinist to this day). Surely it is this aspect of his character that has infl uenced the computer music com-munity as much as his pioneering work in developing software for music programming or hybrid digital performance systems (e.g., GROOVE) or the Radio Baton. Music program-ming software remains largely a communal, freeware world, with Csound, Cmusic, Cmix, common

Publications

Institut National de lAudiovisuel: Portraits Polychromes: Max Mathews

Softcover, 2007, ISBN 978- 2- 86938- 206- 0, 108 pages, Portraits Poly-chromes No. 12, 9; available from GRM Institut National de lAudio-visuel, Maison de Radio France, 116 avenue du Prsident Kennedy, 75220 Paris cedex 16, France; telephone (+33) 1- 56- 40- 29- 88; electronic mail [email protected]; Web www.ina.fr / .

Reviewed by James HarleyGuelph, Ontario, Canada

The infl uence Max Mathews has had on computer music cannot possibly be overstated, except perhaps to call him the Great Grandfather of Techno (as is humorously noted in the vol-ume here under review). I think it is reasonable to assume that the digital revolution in music would have somehow happened without Max (as he is called by pretty much everyone, and as he is eponymously honored by the most popular music program-ming software on the market today), but its form would have been quite dif ferent, and progress may well have proceeded at a slower pace. Max turned 80 years old in November 2006, and his work was celebrated with a MaxFest at the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) in April 2007. This publication (fi rst released in French as Volume 11 of the Portraits Polychromes series) was intended to support that event, also underscoring the 50 years since Maxs fi rst com-puter music results at Bell Telephone Laboratories (BTL) in 1957.

Perhaps one of the most striking

-

96 Computer Music Journal

rigorous attention to such biblio-graphic listings). Max himself con-tributes an annotated catalog of musical compositions (again taking pains to note: Im not a composer. Im not a musician, but Im an inventor of computer- based new instruments (p. 101).

This volume is fi lled out with a science fi ction short story penned by Max in the early 1970s (and fi rst published in Creative Computing in 1977). The story offers a futuristic view of digital music technology, written at a time when digital music was very much an obscure practice by specialists who had trouble fi tting into university music departments, let alone into the consciousness of the general public (Stanley Kubricks citation in 2001: A Space Odyssey of Maxs computer version of Bicycle Built for Two aside).

In conclusion, this is an extremely useful publication for any student of computer music history and commu-nity. The details and references will be valuable, and the story told through the various authors ac-counts is engaging, refl ecting the vitality and energy Max has carried forward in his work and in his sup-port of the activities of many others over the past 50 years. I have not had a chance to compare the French ver-sion of this volume with the English. There are a number of errors in the English edition, pointing to perhaps a rushed translation and editing pro-cess. None of them are particularly serious, just a bit distracting. In addi-tion, there are numerous duplications of facts and anecdotes across the dif-ferent articles that get a bit tiresome as one reads through the book. There may be no way to avoid these, and the duplications will provide useful information for researchers who are perhaps directed to just one of the articles in the book.

contribute an article highlighting Maxs connection to CCRMA, which really began with Mr. Chownings fi rst visit to BTL in 1964 (having read the very same article on computer music in Science that had so capti-vated Mr. Risset). When Max retired from BTL in 1987, he moved to Stan-ford to take up a research position at CCRMA (his longtime friend and colleague John Pierce had already moved there to take up a similar such position). As noted in the article, Maxs activities at CCRMA have covered a wide scope: electronic instruments, synthesis algorithms, music making, publication, and teaching (p. 74). To be more specifi c, the article lists his work on the Radio Baton, an electronic violin pick- up, well- behaved high- Q fi lters, and scanned synthesis. Max has also con-tributed to a number of publications and archives, including the Interna-tional Digital Electro Acoustic Music Archives (IDEAMA) and the Musical Acoustics Research Library (MARL).

Jon Appleton, also a central fi gure in the computer music community, contributes a short article, Maxs importance to the fi eld of electroa-coustic music. His relationship with Max began in 1970, and has contin-ued, more recently as a collaborating composer on the Radio Baton project.

Marc Battier, a pre- eminent histo-rian of electroacoustic / computer music, contributes an annotated catalog of Maxs writings, providing important work sorting out key citations from mere abstracts, and sorting out references that had appeared in bibliographies but which had disappeared from Maxs own listings (modesty being one reason references had been dropped). This is important work, and Mr. Battiers meticulousness is to be commended (other volumes of the Portraits Polychromes could use similarly

computer engineer colleague Fran-ois Genuys had visited Max and seen this novel technology (which was not carried forward beyond the life of that particular computer). Xenakis and his team developed a similar graphic music computer system in France, launching the UPIC in 1978. (Oddly, I do not recall Xenakis ever mentioning this visit to Murray Hill, New Jersey, nor giving credit to Max for the idea.)

Gerald Bennett, Swiss composer and computer musician, was one of the central fi gures of IRCAM as it was established (he left in 1981). He was Director of the Diagonal Depart-ment, meaning that he was to coor-dinate the various collaborations between departments of the institute (between research and music perfor-mance, for example). Max, who had fi rst met with Pierre Boulez in 1970, was engaged as Scientifi c Advisor (he left in 1980), and spent several months there each year through the 1970s. He and Mr. Bennett established a close relationship, one that contin-ued beyond their tenure at IRCAM. Here, Mr. Bennett contributes an article about their cooperation on various research projects at IRCAM. He laments how little infl uence Max (and John Pierce, Maxs colleague / supervisor at BTL, who also pursued research at IRCAM during that period) had on subsequent research there: The relatively small infl uence the originality of two such remark-able scientists as John Pierce and Max had on IRCAMs work is indica-tive of the degree to which IRCAM ultimately failed to become a center of important scientifi c research (p. 60). Max himself is less critical of the institution, and cites among other work Miller Puckettes graphic pro-gramming language (that came to be known as Max).

Chris Chafe and John Chowning

-

Recordings 97

as the boundary between the sonic results of the two realms blurs to the point of erasure. Pieces like Ambos Mundos and Shadow Quartet are fi ne examples of how artists can think across technologies and marshal them for principled explorations.

The album also offers a few note-worthy shortcomings from which we may learn. Gate Beats and The Real Thief of Baghdad are outliers in an otherwise strong set. From the stand-point of my private listening experi-ence, the formers stagnant, stacking development and the latters vague, unconsidered political rhetoric make these more vernacular, more conven-tionally sample- based electronic beat pieces potentially successful in a lounge or open mic situation but certainly disappointing in the com-pany of more formally ambitious works of instrumental composition and the absence of a responsive audience. Perhaps these pieces might fi nd good company among others of the composers like them on a sepa-rate disc, with documentation to provide a clearer context for their creation and performance.

Speaking of formal ambition, a more subtle drawback of the set is that the large shapes of the composi-tions have much in common, which can be cheapening after repeated

specifi c experiences that inspired the music. His music is even funny, a virtue to be lauded in correlation to its current paucity in electronic music. This is especially so in Body Work for Joan La Barbara, for which the composer set to music a list of student questions collected over ten years by University of Portland biol-ogy professor Terry Favero. A whim-sical paean to the mysteries of our own bodies, Mr. Rolnick offers no answers to a cornucopia of zany but mundane inquiries such as: Are boobs just mostly fat?, Why do babies drool?, and the popularly meditated, I saw this Clint East-wood movie where this bad guy took this good guy and laid him out in the sun and sewed his eyelids open; what would happen to the guys eyeballs?

The composers use of computer technology to sample, augment, and manipulate acoustic timbres in these recordings is exemplary, although the performance of these works in a live concert setting might be differently effective. Sonic color is a pillar of Mr. Rolnicks music, and the composer has developed commendable strate-gies for the integration of acoustic and electronic timbres that might be of interest to artists who are similarly interested in an expanded but cohe-sive palette. For example, in Ambos Mundos, the acoustic sounds of a woodwind quartet are heard fi rst in a series of hocketed, punctuating staccatos, each sound rippling in a stereo delay. Shortly after this, an electronic timbre enters, modulating in synchrony with the delay previ-ously heard on the acoustic instru-ments. Specifi cs of unfolding aside, the net effect is a sonic environment in which all sounds naturally exist together. These pieces for acoustic instruments and electronic sound are not usefully considered through the traditional acoustic- electronic binary,

Ive wondered before (in reference to the volume of this series devoted to John Chowning), and must yet again: why has a volume such as this never been published before, in the country of Maxs roots? (To be fair, this volume has been published with the assistance of Stanford Univer-sity.) It probably doesnt much mat-ter, as we are certainly glad that the Institut National de lAudiovisuel in France has seem the importance of undertaking this historical research.

Recordings

Neil Rolnick: Shadow Quartet

Compact disc, innova 631, 2005; available from innova Recordings, 332 Minnesota Street #E- 145, St. Paul, Minnesota 55101, USA; telephone (+1) 651- 251- 2823; fax (+1) 651- 291- 7978; electronic mail [email protected]; Web www.innova.mu / .

Reviewed by Jeffrey TrevioSan Diego, California, USA

This potpourri collection of six pieces has convinced me that Neil Rolnick is my kind of composer. He knows how to make technology part of his music, not his music part of the technology, and he seamlessly and convincingly integrates electron-ically processed acoustic sounds with acoustic ensembles as traditional as string quartet and woodwind quintet. He doesnt have scruples about letting his life experiences into his work; the fi rst selection on the disc is a touching memorial for his departed father, accompanied in the liner notes by an intimate account of the

-

98 Computer Music Journal

Fennesz and Oval. Each component is precisely layered, generating a counterpoint that sustains itself throughout the album.

Focused listening reveals two main components. The fi rst, a wide river of ambient dronethe sum of many noisy tributariesfl ows regally across an arid backdrop of open- mic silence. The harmonies created out of this, amid the detritus of the sur-rounding landscape lend a sense of stately grandeur. This is counteracted by what sounds like a glitch freeway, crossing the ambience at right angles, to create almost the opposite effect. The dusty, scratchy fl ak fl ies across the soundfi eld at tremendous speed, rendering a powerful dynamic that touches the extremes of glitch. Each individual pop highlights the stark contrast both within its own cohort and of the collective ambient drone that underpins the album, as if part of a lively microcosm.

Each track can be broadly de-scribed in these terms, yet each also evokes a separate character of its own. The titles seem to come from Aphex Twins imaginary language school of nomenclature, implying self- conscious obscuritantism. Yemdatem is mechanical and sys-temic, as if a machine working against an encroaching natural force.

Pimmon: Electronic Tax Return

Compact disc, Tigerbeat6 meow016, 2004; available from Tigerbeat6, 2722 19th Avenue, Oakland, California 94606, USA; electronic mail [email protected]; Web www.tigerbeat6.com / .

Pimmon: Secret Sleeping Birds

Compact disc, SIRR sirr0005, 2002; available from SIRR, Rua Cidade Nova Lisboa 220, 5A, 1800 Lisbon, Portugal; electronic mail sirr- ecords@sirr- ecords.com; Web www.sirr- ecords.com / .

Reviewed by Andrew FletcherNewcastle Upon Tyne, UK

Pimmon, a.k.a. Paul Gough, makes music that evokes very physical objects, often sounding like a once- functional machine abandoned to nature. Imagine a hybrid of an electri-cal, mechanical, and chemical appa-ratus that you might fi nd in an old university basement, clunking into life, not quite sure of its purpose anymore, but with power in its veins. Some of its circuits burn out immedi-ately, whereas others vacillate be-tween off and on, having not quite decided if they are awake or not. Set this against the dusty, half- light of a long- forgotten laboratory and you have a typical Pimmon soundscape.

The two albums reviewed here both evoke this eerie imagery, but there are also dialogues with other genres, quirky character traits, and plenty of spirit.

Electronic Tax Return is a live recording taken from an Australian music festival, The Big Day Out, in 2001. First impressions indicate a dominance in the crackle and ambi-ent fi elds. Indeed, the sounds here bring to mind the likes of Christian

listenings. One crutch the composer relies on is to begin with the kind of beguiling timbral hocket just de-scribed, followed closely by a bloom into a plaintive melody. This is refreshing at fi rst, a proposed recon-ciliation between mathematically structured abstraction and intuitive singing. But this listener fi nds the reconciliation unconvincing, al-though honest and well- intentioned. Perhaps it is my Sputnik modernist values, but there is something emotionally exploitative about the kind of sliding, blues- tinged melodies deployed in these pieces against their less conventionally expressive alphabets of rhythm and timbre. The transition between the two can be effective, as it is at fi rst in Ambos Mundos, but even just slightly later in this piece the affect begins to resemble Hans Zimmers soundtrack for the fi lm Driving Miss Daisy. This is the usual modernist accusation of decadent sentimentality, and Mr. Rolnick, to his credit, lays his own values out clearly in his liner notes to Fiddle Faddle for violin and live electronics:

Fiddle Faddle in my cookbook is described as: butter toffee with almonds over popcorn . . . My dictionary describes it as trivial nonsense. In either case, its sweet and enjoyable. Not neces-sarily nourishing or profound, but not too bad for you. What more could you ask of a piece which allows you to show off your violin chops while engag-ing in some pretty intimate interaction with a computer? (CD liner notes)

I understand and appreciate this outlook, especially given much of computer musics suffocating gravity, but sometimes, Mr. Rolnick, you should ask more.

-

Recordings 99

Feather Prophet, although this fi ts harmoniously with the conceit of not taking things too seriously and, given the overall quality of the textures and transformations throughout, leavens the album.

The composer never gives much away in his inlays and this is no exception. Most of the tracks bear some reference to birds and this is refl ected in the lighter than air quality of even the heaviest tracks. This could be put down to clever equalization or mastering, but the music also contains deeper layers of reference, fl uttering and pecking its way through a variety of potentially avian environments. My favorite piece, Amarelo plido, quase branco, evokes distant churches under threat from bulldozers. A lonely sirens call throughout laments the loss of this habitat, whereas the underlying drone hints at the imminent threat. The track itself is ambiguous, but if one thinks of birds while listening to it, its evocation becomes magnifi ed. This theme holds the album together, yet also allows the freedom and space required to demonstrate Pimmons virtuosity. It grates me to say this, but this focus allows the pieces to fl y.

The tracks are exquisitely ordered and mixed, yet seem to cover a lot of ground in not very much time, giving the impression that any concentrated listening is wasted, because by the time the album reaches its end, there has been little time to refl ect on it as an object of study. It is enjoyably elusive. I do not say this to fl atter the artist, rather, this refl ects on the nature of the listener more than any-thing else. There is a lot of informa-tion packed into this albums 53'40", and at times it does not dwell long enough on the more deserving soundscapes. But again, this comes down to subjective interpretation. Some listeners may fi nd it a little lumpy and badly paced, whereas

corners being turned in too short a space of time. Confi rming the al-bums live status, a sickeningly enthusiastic compre blurts over the end: That was Pimmon . . . And while he was doing that, he lodged his tax return electronically. And the good news is: hes getting 86 dollars back. This comes across as a sly wink, bringing listeners rudely back to reality, defying them to get too involved in what is often seen as an erudite and abstracted genre.

Secret Sleeping Birds is a far gentler affair. Where Electronic Tax Return explored variations on the glitch / ambient axis, this album takes a broader view, covering a range of textures and environments. Here, Mr. Gough examines the micro- and macroscopic, simultaneously keeping both perfectly in focus. This yields a kind of tension, a positive energy, which is at fi rst diffi cult to holdlike trying to concentrate on two items at the same timebut ulti-mately drives the album.

Offsetting this, jaunty little loop- based melodies crop up regularly, bursting the tension that seems so perfectly crafted and thus providing the release required for a well- balanced work. This concern for balance appears to be a central theme of the album, which spans a variety of soundscapes, from the darkly organic through celestial and droney and extending into whacked- out, synthesizer- driven craziness. But it is the balance between carefully con-structed environments and fun little interludes that provides Secret Sleeping Birds with its momentum. Pimmons music is never too far from the humorous, though this does not compromise the immersive quality and attention to detail he injects. Again, this comes across as a nod to the surrealist movement. Occasional giveaways poke through, such as a particularly ring- modulated effect in

Beach Party emerges from this initial chaos, but increases in character from the previous track. Again, sys-tems come into play, but with more internal dialogue. Vovul lj has a more ambient base, with sublime defi ni-tion and some of the harshest sounds on the album. The glitch and drone interlock beautifully, demonstrating exactly how this music is designed to work. Hints of melody poke through occasionally, reifying the design ele-ment and calling into question any aleatoric assumptions that may be drawn. Smiggins Whole / loss carries a melodic and haunting refrain, permeating the auto / electrical fore-ground noise against a perpetual backdrop of dissonance. Again, over-grown machinery ceded to nature is the feel here, casting a nod to the surrealist concept of allowing nature to (re)colonize the new.

Ditoko yields distant car horns and bowed cymbals wrangling for control of the soundscape, and in this respect comes close to an electroacoustic composition. The contrast is good, but its not gentle listening. Arc Of Crown And Feather (despite sound-ing like an English pub) gets under the skin in a particularly effective manner; its uncomfortable and itchy, even creeping into psychosomatic territory. The detail is marred slightly by a delay line that hasnt quite been buried fully, betraying the mechanics and eroding the overall ambience. Pulsebuzzkid seals the album with searing, distant sirens, evoking Brian Eno, but offset against precision glitch.

Despite being fi rmly grounded within the microtonal / glitch fi eld, this album puts out tendrils to diverse reference points. The com-poser has developed their music organically, allowing it to ebb and fl ow at their infl uencess whim. It makes for an interesting listen, al-though some may fi nd too many

-

100 Computer Music Journal

holds the album together cerebrally, but also makes itself apparent just often enough to be more or less omnipresent. It is this sense of fun and exploration, as well as an air of wit that really holds this disparate collection of soundscapes together.

Paul Gough is not just a glitch composer. He handles microtonality and electroacoustics along with more conventional loop- based music, plus the obligatory noise, with aplomb and relish. These are mixed beauti-fully and both albums have a distinct identity, whilst also being recogniz-able as the work of Pimmon. If you listen to a lot of ambient / avant- garde / glitch music, this will come as a juicy surprise, providing new colors in an often mundane fi eld.

pensated for by a deftness of touch and a humor rarely achieved on some of the drier output that can be found in this genre.

The contrast between these two albums is palpable. Both bristle with immediacy, yet Electronic Tax Re-turn conveys a more arid style, sug-gesting that the composer may not be completely comfortable playing live. This is conjecture, but the former seems somewhat more conservative and less willing to take risks, al-though it does sound a little more cohesive. It works in its own right, and this observation is only based on a comparison of the two albums. Secret Sleeping Birds on the other hand, showcases Pimmons diversity. Each piece is tied together in certain intangible ways. The bird theme

others will inevitably hear it as an exciting rollercoaster ride through the gamut of this artists sonic arsenal. The variety ensures that there will be something to please everyone, without alienating dedi-cated glitch fans. This constitutes a shining example of a talented artist with itchy feet.

The sounds themselves, though diverse, tend to center on loop- based analog noise, transformed and mangled by some usually quite subtle digital methods. At times, electroa-coustic infl uences can be heard, whereas at others, Pimmon betrays a nod to the likes of Vangelis (from the Bladerunner era) in his more atmo-spheric evocations. The bird theme sometimes becomes lost beneath whimsy, but this is more than com-

/ColorImageDict > /JPEG2000ColorACSImageDict > /JPEG2000ColorImageDict > /AntiAliasGrayImages false /CropGrayImages true /GrayImageMinResolution 300 /GrayImageMinResolutionPolicy /OK /DownsampleGrayImages false /GrayImageDownsampleType /Average /GrayImageResolution 300 /GrayImageDepth -1 /GrayImageMinDownsampleDepth 2 /GrayImageDownsampleThreshold 1.50000 /EncodeGrayImages true /GrayImageFilter /DCTEncode /AutoFilterGrayImages true /GrayImageAutoFilterStrategy /JPEG /GrayACSImageDict > /GrayImageDict > /JPEG2000GrayACSImageDict > /JPEG2000GrayImageDict > /AntiAliasMonoImages false /CropMonoImages true /MonoImageMinResolution 1200 /MonoImageMinResolutionPolicy /OK /DownsampleMonoImages false /MonoImageDownsampleType /Average /MonoImageResolution 1200 /MonoImageDepth -1 /MonoImageDownsampleThreshold 1.50000 /EncodeMonoImages true /MonoImageFilter /CCITTFaxEncode /MonoImageDict > /AllowPSXObjects false /CheckCompliance [ /None ] /PDFX1aCheck false /PDFX3Check false /PDFXCompliantPDFOnly false /PDFXNoTrimBoxError true /PDFXTrimBoxToMediaBoxOffset [ 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 ] /PDFXSetBleedBoxToMediaBox true /PDFXBleedBoxToTrimBoxOffset [ 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 ] /PDFXOutputIntentProfile () /PDFXOutputConditionIdentifier () /PDFXOutputCondition () /PDFXRegistryName () /PDFXTrapped /False

/Description > /Namespace [ (Adobe) (Common) (1.0) ] /OtherNamespaces [ > /FormElements false /GenerateStructure false /IncludeBookmarks false /IncludeHyperlinks false /IncludeInteractive false /IncludeLayers false /IncludeProfiles false /MultimediaHandling /UseObjectSettings /Namespace [ (Adobe) (CreativeSuite) (2.0) ] /PDFXOutputIntentProfileSelector /DocumentCMYK /PreserveEditing true /UntaggedCMYKHandling /LeaveUntagged /UntaggedRGBHandling /UseDocumentProfile /UseDocumentBleed false >> ]>> setdistillerparams> setpagedevice

![Artículo universidad de antioquia[1]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/55b97036bb61ebe8798b4753/articulo-universidad-de-antioquia1.jpg)