Article Thebes in the First Millennium 2014 Musso-Petacchi

-

Upload

simone-musso -

Category

Documents

-

view

48 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Article Thebes in the First Millennium 2014 Musso-Petacchi

Thebes in the First Millennium BC,

Edited by Elena Pischikova, Julia Budka and Kenneth Griffin

This book first published 2014

Cambridge Scholars Publishing

12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Copyright © 2014 by Elena Pischikova, Julia Budka, Kenneth Griffin and contributors

All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

ISBN (10): 1-4438-5404-2, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5404-7

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword …………………………………………………………………xi Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………...xv Part A: Historical Background Chapter One ……………………………………………………………....3 The Coming of the Kushites and the Identity of Osorkon IV Aidan Dodson Part B: Royal Burials: Thebes and Abydos Chapter Two ……………………………………………………………..15 Royal Burials at Thebes during the First Millennium BC David A. Aston Chapter Three …………………………………………………………....61 Kushites at Abydos: The Royal Family and Beyond Anthony Leahy Part C: Elite Tombs of the Theban Necropolis

Section 1: Preservation and Development of the Theban Necropolis

Chapter Four ………..………………………………………………….101 Lost Tombs of Qurna: Development and Preservation of the Middle Area of the Theban Necropolis Ramadan Ahmed Ali Chapter Five ……………………………………………………………111 New Tombs of the North Asasif Fathy Yaseen Abd el Karim

vi Table of Contents

Section 2: Archaeology and Conservation Chapter Six ……………………………………………………………..121 Kushite Tombs of the South Asasif Necropolis: Conservation, Reconstruction, and Research Elena Pischikova Chapter Seven ………………………………………………………….161 Reconstruction and Conservation of the Tomb of Karakhamun (TT 223) Abdelrazk Mohamed Ali Chapter Eight …………………………………………………………..173 The Forgotten Tomb of Ramose (TT 132) Christian Greco Chapter Nine …………………………………………………………...201 The Tomb of Montuemhat (TT 34) in the Theban Necropolis: A New Approach Louise Gestermann and Farouk Gomaà Chapter Ten ………………………………………………………….....205 The “Funeral Palace” of Padiamenope (TT 33): Tomb, Place of Pilgrimage, and Library. Current research Claude Traunecker Chapter Eleven …………………………………………………………235 Kushite and Saite Period Burials on el-Khokha Gábor Schreiber

Section 3: Religious Texts: Tradition and Innovation Chapter Twelve ………………………………………………………...251 The Book of the Dead from the Western Wall of the Second Pillared Hall in the Tomb of Karakhamun (TT 223) Kenneth Griffin Chapter Thirteen ……………………………………………………….269 The Broad Hall of the Two Maats: Spell BD 125 in Karakhamun’s Main Burial Chamber Miguel Angel Molinero Polo

Table of Contents vii

Chapter Fourteen ……………………………………………………….295 Report on the Work on the Fragments of the “Stundenritual” (Ritual of the Hours of the Day) in TT 223 Erhart Graefe Chapter Fifteen …………………………………………………...…….307 The Amduat and the Book of the Gates in the Tomb of Padiamenope (TT 33): A Work in Progress Isabelle Régen Section 4: Interconnections, Transmission of Patterns and Concepts, and Archaism: Thebes and Beyond Chapter Sixteen ………………………………………………...………323 Between South and North Asasif: The Tomb of Harwa (TT 37) as a “Transitional Monument” Silvia Einaudi Chapter Seventeen ………………………………………………...……343 The So-called “Lichthof” Once More: On the Transmission of Concepts between Tomb and Temple Filip Coppens Chapter Eighteen ……………………………………...………………..357 Some Observations about the Representation of the Neck-sash in Twenty-sixth Dynasty Thebes Aleksandra Hallmann Chapter Nineteen ……………………………………………………….379 All in the Detail: Some Further Observations on “Archaism” and Style in Libyan-Kushite-Saite Egypt Robert G. Morkot Chapter Twenty …………………………………………...……………397 Usurpation and the Erasure of Names during the Twenty-sixth Dynasty Carola Koch

viii Table of Contents Part D: Burial Assemblages and Other Finds in Elite Tombs

Section 1: Coffins Chapter Twenty-one ………………………………………...………….419 The Significance of a Ritual Scene on the Floor Board of Some Coffin Cases in the Twenty-first Dynasty Eltayeb Abbas Chapter Twenty-two …………………………………………….……..439 The Inner Coffin of Tameramun: A Unique Masterpiece of Kushite Iconography from Thebes Simone Musso and Simone Petacchi Chapter Twenty-three ……………………………………………….…453 Sokar-Osiris and the Goddesses: Some Twenty-fifth–Twenty-sixth Dynasty Coffins from Thebes Cynthia May Sheikholeslami Chapter Twenty-four …………………………………………………...483 The Vatican Coffin Project Alessia Amenta

Section 2: Other Finds Chapter Twenty-five ……………………………………………...……503 Kushite Pottery from the Tomb of Karakhamun: Towards a Reconstruc-tion of the Use of Pottery in Twenty-fifth Dynasty Temple Tombs Julia Budka Chapter Twenty-six ……………………………………………….……521 A Collection of Cows: Brief Remarks on the Faunal Material from the South Asasif Conservation Project Salima Ikram Chapter Twenty-seven …………………………………………………529 Three Burial Assemblages of the Saite Period from Saqqara Kate Gosford

Table of Contents ix

Part E: Karnak Chapter Twenty-eight ………………………………………….………549 A Major Development Project of the Northern Area of the Amun-Re Precinct at Karnak during the Reign of Shabaqo Nadia Licitra, Christophe Thiers, and Pierre Zignani Chapter Twenty-nine …………………………………………………...565 The Quarter of the Divine Adoratrices at Karnak (Naga Malgata) during the Twenty-sixth Dynasty: Some Hitherto Unpublished Epigraphic Material Laurent Coulon Chapter Thirty …………………………………………………….……587 Offering Magazines on the Southern Bank of the Sacred Lake in Karnak: The Oriental Complex of the Twenty-fifth–Twenty-sixth Dynasty Aurélia Masson Chapter Thirty-one ………………………………………………..……603 Ceramic Production in the Theban Area from the Late Period: New Discoveries in Karnak Stéphanie Boulet and Catherine Defernez Chapter Thirty-two ……………………………………………..………625 Applications of Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) in the Study of Temple Graffiti Elizabeth Frood and Kathryn Howley Abbreviations …………………………………………………………..639 Contributors ……………………………………………………………645 Indices …………….……………………………………………..……..647

FOREWORD

“Egypt in the First Millennium BC” is a collection of articles, most of which are based on the talks given at the conference of the same name organised by the team of the South Asasif Conservation Project (SACP), an Egyptian-American Mission working under the auspices of the Ministry of State for Antiquities (MSA), Egypt in Luxor in 2012. The organisers of the conference Elena Pischikova, Julia Budka, and Kenneth Griffin in-tended to bring together a group of speakers who would share the results of their recent field research in the tombs and temples of the Twenty-fifth and Twenty-sixth Dynasties in Thebes and other archaeological sites, as well as addressing a variety of issues relevant to different aspects of Egyptian monuments of this period.

Papers based on the talks of the participants of the conference form the bulk of this volume. However, we found it possible to include the papers of a few scholars who could not attend the conference, but whose contri-butions are pertinent to the main themes of the conference and could en-rich the content of the present volume. Therefore, this volume covers a much wider range of sites, monuments, and issues as well as a broader chronological span. Discussions of the monuments of Abydos and Saqqara, along with the Libyan tradition, enrich the argument on intercon-nections, derivations, innovations, and archaism. The diversity of topics cover the areas of history, archaeology, epigraphy, art, and burial assem-blages of the period.

Aidan Dodson deliberates on chronological issues of the early Kushite state by re-examining the identity of Osorkon IV and related monuments. His paper gives a historical and cultural introduction to the Kushite Period and the whole volume.

The papers of the General Director of the Middle Area of the West Bank Fathy Yaseen Abd el Karim, and Chief Inspector of the Middle Area Ramadan Ahmed Ali, open a large section in the volume dedicated to different aspects of research and fieldwork in the Theban necropolis. They concern the preservation and development of the necropolis, an incredibly important matter which assumed a new dimension after the demolition of the Qurna villages and clearing of the area being undertaken by the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE) teams. Numerous tombs found under the houses need immediate safety measures to be applied as well as archaeological and research attention. The conservation, preservation, and recording of the elite tombs in the area are amongst the most relevant issues in the Theban necropolis today.

xii Foreword

David Aston and Anthony Leahy examine the royal burials of Thebes and Abydos. Both papers present a remarkably large number of burials related to the royal families of the First Millennium BC. This time period in the Theban necropolis is traditionally associated with elite tombs, with the royal monuments often neglected. Research on the royal aspect of these sites provides a deeper perspective to the study of the elite tombs of the period.

The papers on the elite tombs of the Theban necropolis address a vari-ety of aspects of work in this group of monuments such as archaeology, conservation, epigraphy, and burial assemblages, as well as relevant issues as archaism and innovations of the decoration and interconnections be-tween the tombs of different parts of the necropolis. The areas of archae-ology and conservation of the necropolis are presented by the papers of the Director of the SACP Elena Pischikova, and its leading conservator Abdelrazk Mohamed Ali. These papers give a summary of the re-discovery, excavation, conservation, reconstruction, and mapping work done in the tombs of Karakhamun (TT 223) and Karabasken (TT 391) over a period of eight years, with emphasis on the 2012 and 2013 seasons. This section is complemented by a paper on the fieldwork in another “forgotten” tomb of the South Asasif necropolis, Ramose (TT 132), by Christian Greco. The archaeological work in the South Asasif necropolis has resulted in the uncovering and reconstruction of a large amount of new architectural, epigraphic, and artistic information, some of which is presented in this volume for the first time.

The new project in the tomb of Montuemhat (TT 34), undertaken by Louise Gestermann and Farouk Gomaà, is another invaluable piece of information which, together with the work of Greco in the tomb of Ramose, and Molinero Polo in the tomb of Karakhamun, modifies our understanding of Kushite and early Saite burial compartments and their semantics within the tomb complex. The paper on the Twenty-fifth to Twenty-sixth Dynasty tombs of el-Khokha by Gábor Schreiber widens our perception of the geographic disbursement of Kushite tombs in the Theban necropolis. The amount of intrusive Twenty-fifth Dynasty burials within the primarily New Kingdom site of el-Khokha gives confidence that we may expect similar results from the numerous Qurna missions. Special attention paid to such intrusive burials in different areas may build a solid basis for our better understanding of Kushite presence and activities in Thebes in the future.

The epigraphical studies of Kenneth Griffin, Miguel Molinero Polo, and Erhart Graefe within the tomb of Karakhamun, and Isabelle Régen in the tomb of Padiamenope, concern the reflection of tradition and innova-

Foreword xiii

tions in the texts of the Book of the Dead, the Amduat, the Book of the Gates, and the Ritual of the Hours of the Day, as well as their new archi-tectural and contextual environment. The comparative research of these texts in different tombs will eventually lead to a better understanding of the reasons for selections of certain traditional texts, reasons for their ad-justments, as well as their interpretations in the new contexts of temple tombs of the period.

Although Kushite and Saite tombs demonstrate a rich variety of archi-tectural, textual, and decorative material they are all interconnected by certain aspects and concepts. The next group of papers by Silvia Einaudi, Filip Coppens, Robert Morkot, Aleksandra Hallmann, and Carola Koch concern such aspects, relevant to most of the monuments. Silvia Einaudi raises the incredibly important question of interconnections and inter-influences between the tombs of the Theban necropolis, origins of certain patterns and traditions within the necropolis, and their transmissions from tomb to tomb. Filip Coppens and Aleksandra Hallmann concentrate on smaller elements of the tomb complexes, such as a piece of garment or a single architectural feature, to track it within a group of monuments. Thus, Coppens traces similarities and differences in the Sun Court decoration in different tombs, its connection with the temple concept, and discusses its symbolic and ritual meaning in temple tombs. Robert Morkot discusses the sources and chronological developments of archaism in royal and elite monuments. Carola Koch addresses the Saite approach to Kushite monu-ments by re-examining the phenomenon of the erasure of Kushite names during the Twenty-sixth Dynasty.

A large group of papers on the burial assemblages and other finds in elite tombs enrich and expend the discussion of the burial complexes of the First Millennium BC. Eltayeb Abbas, Simone Musso and Simone Petacchi, Cynthia Sheikholeslami, and Alessia Amenta discuss the issues of construction techniques, workshops, and iconography of coffin decora-tion and its ritual meaning. Julia Budka and Salima Ikram discuss finds in the tomb of Karakhamun. Budka analyses Kushite pottery found in the burial compartment and its usage in a Twenty-fifth Dynasty temple tomb, while Ikram remarks on the faunal material from the First Pillared Hall. Kate Gosford broadens the boundaries of the discussion with some burial assemblages from Saqqara.

The last section of the volume is dedicated to the new archaeological research at Karnak presented by Nadia Licitra, Christophe Thiers, Pierre Zignani, Laurent Coulon, Aurélia Masson, Stéphanie Boulet, and Catherine Defernez. Their papers concern different areas of the temple complex such as the temple of Ptah, the Treasury of Shabaqo, the “palace”

xiv Foreword of the God’s Wife Ankhnesneferibre in Naga Malgata, and offering maga-zines as well as the new evidence of ceramic production at Karnak in the chapel of Osiris Wennefer. Another Karnak paper introduces a new tech-nology, with Elizabeth Frood and Kathryn Howley describing the use of Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) as a means of studying graffiti at the site.

Most of the information included into this volume is being published for the first time. We feel that the research presented here brings together a range of current studies on royal and elite monuments of the period, put-ting them into a wider context and filling some gaps in First Millennium BC scholarship. This time period is still one of the least researched and published area of study in Egyptology despite the numerous recent devel-opments in field exploration and research. The present volume offers a discussion of the First Millennium BC monuments and sites in all their complexity. Such aspects of research as tomb and temple architecture, epigraphy, artistic styles, iconography, palaeography, local workshops, and burial assemblages collected in this publication give a new perspective to the future exploration of these aspects and topics. We hope that the present volume will inspire new comparative studies on the topics dis-cussed and bring First Millennium BC scholarship to a new level. .

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank the Minister of Antiquities Mohamed Ibrahim and the Ministry of State for Antiquities for their support in organising the conference “Thebes in the First Millennium BC” in Luxor in October 2012 and permission to work in the South Asasif necropolis. We are grateful for the support our Egyptian-American team, the South Asasif Conservation Project, has received over the years from Dr. Mohamed Ismail Khaled, Director of the Department of Foreign Missions MSA, Dr. Mansour Boraik, Director General of Luxor Antiquities until 2013; Ibrahim Soliman, Director of Luxor Antiquities; Dr. Mohamed Abd el Aziz, Gen-eral Director for the West Bank of Luxor; Fathy Yassen Abd el Kerim, Director of the Middle Area; Ramadan Ahmed Ali, Chief Inspector of the Middle Area; Ahmed Ali Hussein Ali, SCA Chief Conservator and Director of the Conservation Department of Upper Egypt; Afaf Fathalla, General Director of the Conservation Department of Upper Egypt; the MSA conservation team; and all our team members and volunteers. We are very grateful to our sponsors, IKG Cultural Resources, directed by Anthony Browder (USA), and the South Asasif Conservation Trust, di-rected by John Billman (UK). Without all this help and support we would not have been able to accomplish the field work and research included in the present volume.

Special thanks to the participants of the conference, particularly to our Luxor colleagues Nadia Licitra, Christophe Thiers, Pierre Zignani, Laurent Coulon, Claude Traunecker, Isabelle Régen, Louise Gestermann, and Farouk Gomaà who showed their sites to the participants.

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

THE INNER COFFIN OF TAMERAMUN: A UNIQUE MASTERPIECE OF KUSHITE

ICONOGRAPHY FROM THEBES

SIMONE MUSSO & SIMONE PETACCHI* Consultant curators for the Egyptian collection,

Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan

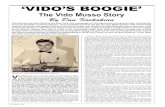

Abstract: The anthropoid inner wooden coffin of the lady Tameramun, “Singer of the Inner of Amun” in Thebes during the Kushite Period, is stored in Pogliaghi’s villa at the Sacro Monte di Varese (Italy). It was given scholarly attention in the 1970s, but has not been studied since. In this article, the coffin has been re-examined with regards to stylistic, iconographical, and textual criteria providing images of the coffin that have never been published before. The coffin under discussion in this paper belongs to a small collection of Egyptian antiquities owned by an important sculptor and professor of arts at the Academy of Brera (Milan), Ludovico Pogliaghi, who lived between the end of late nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth cen-tury. He is remembered mainly for being responsible for commissioning the bronze gateway of the Saint Ambrogio cathedral in Milan. Pogliaghi spent a large part of his life in his villa at Sacro Monte of Varese, a vast estate located on the peak of the mountain. He used to live and work in his studio apartments where he assembled antiquities of different time periods, ethnographic items, in addition to an innumerable amount of sketches, models, and art works of his own creation.

One of the relevant pharaonic items of the villa is the anthropoid coffin of a lady named Tameramun, now in the possession of the Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan (fig. 22-1). According to a recent cata-logue made by the authors, her coffin has the inventory number CEP10 (=

* We would like to express our gratitude for the permission to study this coffin and for the technical assistance in Milan and in Varese to all the members of the “Collegio dei dottori” of the Ambrosiana, in particular to Dr. A. Rocca and his collaborators, Drs. E. Fontana and E. Mantia.

440 Chapter Twenty-two Collezione egizia Pogliaghi). It consists of an anthropoid, inner wooden case and lid,1 intended to contain the mummy of the deceased lady to whom it belonged. The Varese piece was made from sycamore and rests on a quadrangular wooden platform to which it has been fixed by an iron casing provided with hinges added in modern times—likely an addition by Pogliaghi in order to assist with the opening of the coffin lid.

Fig. 22-1: Tameramun’s inner coffin, front view (photo by the authors).

Both lid and case are largely complete and are in a fairly good state of

preservation. A part of the nose is missing and there is a long lateral break on both the long sides of the coffin, neither of which affects the general reading of the artefact (fig. 22-2). The lid and case were richly decorated with friezes and figured registers on the external surface while the inner

1 Length: 164cm, width: 24.5cm, height of face: 14.5cm.

The Inner Coffin of Tameramun 441

part is only covered with white plaster without decoration. However, traces of a black substance have been recorded on the interior surface of the case.2

Fig. 22-2: Tameramun’s face with her broken nose (photo by the authors). Tameramun’s face was elegantly sculptured and rendered with a rose

coated colour, in a natural way, with large eyes that have been slightly incised and painted in black ink. An elaborate tripartite wig surrounds the face, exposing only the ears. A vulture headdress covers the top of the head and part of the forehead, extending over the lateral tails.

The scenes from the coffin have been divided up into registers, each of which have been given a corresponding letter for easy identification (fig. 22-3).

The shoulders and neck are adorned with a coloured wesekh-collar, consisting of floral motifs. The first register begins at the base of the neck (A), with a figured pectoral cavetto cornice structure depicting Maat with the sun-disc between a djed-pillar and tyet-symbol (fig. 22-4). Below, on the centre of the breast, the ubiquitous scene of a winged ram headed

2 A few samples have been sent to chemical laboratories of the University of Pisa for analysis, not yet available at the time of publication.

442 Chapter Twenty-two figure, a solar image with sun-disc, uraeus, and corkscrew horns. On top of the uraeus a second solar-disc is located between the Hathoric horns. The falcon body is represented in a protective act with wings outstretched. As usual, the claws grasp shen-rings to enforce the regenerating power of the circuit of the sun, giving life to all creatures, and in this case guaranteeing the resurrection of Tameramun (fig. 22-5). At each side of the ram-headed falcon wings, a line of hieroglyphs is painted on a yellow background. The inscription is framed by the rishi-friezes in red, green, and blue components and reads as follows: BHdt(y) nTr aA nb pt “Horus of Behdet, the Great God, Lord of Heaven”.

Fig. 22-3: The figured and inscribed registers of the coffin

(drawing by the authors).

The Inner Coffin of Tameramun 443

Fig. 22-4: Register A (photo by the authors).

Fig. 22-5: The ram headed winged god on the breast (photo by the authors).

Beneath the rishi-friezes, within both the parallel lateral registers (B1

and B2), Osiris is followed by two of the sons of Horus. All are repre-sented standing, looking towards the inner part of the coffin, and facing a uraeus who wears the white crown (B1) and the red crown (B2). The most prominent and striking feature of this iconography is the unique and personal rendering of the four sons of Horus in a female appearance (fig. 22-6). It is clear that Tameramun identified herself with all these

444 Chapter Twenty-two characters, particularly as the canopic gods are all represented as females. They are shown with green bodies, wearing a long and tight red robe that exposes only the breast, in addition to a cone atop their heads. The only character who differs from the others on these registers is the one repre-senting Tameramun, with a rose skin rather than a green one. In addition, the likely identification of Tameramun with these funerary genii is con-firmed by the presence of her name on the top of B1 and B2—where in the case of other figures the names of the funerary divinities appear.

Fig. 22-6: Registers B1 and B2 (photos and drawings by the authors).

Immediately below the ram-headed sun-god is another representation

of a falcon in the same attitude of the previous winged god, this time in the guise of Re-Horakhty. The Htp-di-nswt formula, addressed to Osiris Wennefer on behalf of Tameramun, is located beneath the wings of Re-Horakhty, between two horizontal rishi-bands (fig. 22-7). Beneath this is the Abydos fetish, the reliquary containing the head of Osiris, which is surmounted by a crown with double feathers, solar-disc, and uraeus.

On the right side of the Abydos fetish (C2) is another frieze of images depicting Anubis standing with his hand on the crown in a protective act. He is followed by Osiris, who is shown with green skin and wearing the

The Inner Coffin of Tameramun 445

dress of the living in contrast to the upper registers where he was repre-sented mummiform. Osiris leads Tameramun by the hand, with the de-ceased wearing a long white robe, pleated in red lines, covering arms and legs. Additionally, she has a cone on the head, with a lotus flower, while she has her left hand raised in adoration.

Fig. 22-7: Re-Horakhty between registers B1–B2 and C1–C2

(photo by the authors).

446 Chapter Twenty-two

The left side (C1) is similar to the previous, this time with Horus, wearing the double crown, followed by Thoth, who plays the role of chap-erone to the deceased. Directly above these two scenes are two horizontal bands of hieroglyphs, surrounded by a rishi-frieze, which are to be read from right to left. The text reads as: Dd mdw <i>n Ra-¡r-Axty Hry nTrw pri m Axt di=f Htp DfA.w Hs<t> &A-mr-Imn mAa<t>-xrw, “Words spoken by Re-Horakhty, Lord of the Gods, the one who comes forth from the horizon, in order that he might give food provisions for the Singer Tameramun, true of voice”.

Beneath the Abydos fetish there is a column of text finishing at the level of the foot. Here, the inscription represents another Htp-di-nswt formula with a few important additions concerning the role of Tameramun. She is identified as the Hs<t> Xnw <n> Imn.3 Furthermore, two registers framed on the top and bottom by rishi-friezes are also present beneath the fetish. On both sides, (D1 and D2), Re is represented as a falcon, resting on the nwb-sign and with a solar disc on his head. In both cases, his wings surround a wAs-sign, in addition to a wedjat-eye resting on a nwb-sign. The opened wings face the Abydos fetish with the name of the god, Re, written in short columns above his head.

Between the lower rishi-band and the central inscription, the scribe added a protection formula made by Wepwawet of the north for Tameramun. On the foot of the coffin, flanking this protection formula, there are two representations of Wepwawet of the west and the east respectively (E1 and E2), crouching upon on a shrine, with a sekhem-sceptre in front of the god and a winged uraeus with a sun disc projecting from the front (fig. 22-8).

Concerning the outer case, at the level of the shoulders there are two protective funerary genii who are depicted kneeling, each grasping a knife and looking towards the inner part of the coffin (F1 and F2, fig. 22-9). The figure on the right has a serpent shaped head with a false beard and two high feathers on top of the head. The other figure is damaged and therefore lacking a large section of his head and chest. The names of either figure are not present although it seems likely that they represent the knife-bearing guardian gods.

Two blue horizontal lines separate the guardians and a large central motif that occupies the remainder of the coffin (G). Here, a large djed-pillar, representing the god Osiris, is depicted above a nwb-sign. The pillar has human hands, which grasp nekhakha-sceptres, while the top is crowned with the tjeni-crown. Furthermore, the figure is flanked on both

3 Yoyotte 1961, 45; Teeter and Johnson 2009, 25–29.

The Inner Coffin of Tameramun 447

sides with a pair of wedjat-eyes at the head and two cobras with solar disc protruding from the waist area.

Fig. 22-8: The western and eastern Wepwawet on the foot of the lid,

registers E1 and E2 (photo by the authors). The personification of the djed-pillar is a rare and important element

that corresponds to “Type III” of Amann’s classification, i. e. semi-anthropomorphic representations of this Osirian emblem, a typical sym-bolic element used during the Twenty-second–Twenty-fifth Dynasties (fig. 22-3, right side).4 The dating of the coffin therefore depends on stylistic 4 Amann 1983, 52–56.

448 Chapter Twenty-two features of the images painted on the coffin, thus making it likely that it dates to the Twenty-fifth Dynasty category of Theban style coffins, but with an unusual mix of elements, both from the beginning and its late phase. In fact, according to the classification of Taylor, developed over the past decade, the general layout and division of Tameramun’s lid can be assigned to “design 3”,5 generally in use from the Twenty-second to early Twenty-fifth Dynasties. This includes a higher ram-headed winged sun-god on the breast, supplemented in this case by another winged figure just below, the Abydos fetish in the central part with an inscribed band running to the foot of the coffin, and symmetrical compartments painted and written on the lateral sides.

Fig. 22-9: The genii on the right and left shoulders of the case, registers F1

and F2 (photos by the authors). The originality of the decoration of the frontal case has no parallel in

the iconography of examples dating to either earlier or later periods.6 Tameramun’s lid is the only evidence so far known to demonstrate a personal emphasis of the canopic deities as a representation of the deceased. For this reason, they have been depicted in a living dress and with the same attitude as the singer. Thus, there is nothing strange in the 5 Taylor 2003, 109. 6 This theory was confirmed by John Taylor after a preliminary examination of the coffin. Personal communication.

The Inner Coffin of Tameramun 449

choice of the artist to substitute the only son of Horus with all the human traits, Imsety, with a real portrait of the deceased Tameramun. Even if their style is innovative, the shape of the unguent cone corresponds to Taylor’s “type 2”, in which a vegetal green matter flanks an irregular shaped cone.7

On the frontal surface of Tameramun’s coffin, the lady wears two different types of dresses: on the upper left register (B1, fig. 22-6) she is in a tight fitting red robe with only one strap, a typical but later Twenty-fifth Dynasty attire that corresponds to “type 9” of Taylor’s classification,8 even if it represents a variant because of the lack of the second strap. Below, on the lower registers (C1 and C2, figs. 22-7 and 22-10), the deceased wears another long transparent and pleated robe, which fits into “type 10” of the same classification (Twenty-fifth and Twenty-sixth Dynasties).9 Moreover, the presence of Osiris wearing a dress of the living (C2, fig. 22-10) is also uncommon. The closest parallel to this iconography can be found on the coffin of Padiashaikhet from the Nicholson Museum in Sydney (inventory number R28) but in this case, Osiris is depicted alone.10

Fig. 22-10. Register C2: Tameramun accompanied by Osiris in a living dress

(photo by the authors).

7 Taylor 2003, 101–102. 8 Taylor 2003, 100. 9 Taylor 2003, 100. 10 Taylor 2006, pl. 49d.

450 Chapter Twenty-two

In addition, the position of the two guardians gods holding a knife on the left and right shoulders of the outer case of the coffin is, however, quite unusual although it does confirm the general freedom of the artist(s) in rendering stereotypical figures and motifs. In fact, these deities are generally depicted either on the inner case or on its lateral sides.

In brief, the coffin is only apparently standard: the layout of the regis-ters, early in date, does not match with the other stylistic elements (dresses, unguent cones), rather later; however, its uniqueness is well con-firmed by other uncommon features (the female appearance of the four sons of Horus, the position of the guardian gods on the shoulders of the outer case), which can probably explain an archaising and experimental solution of the artist(s).

The inscriptions on the coffin are largely uninformative, providing only the name of the owner and her title “Singer of the Inner of Amun”. At present, Tameramun is unknown from any other monuments or funerary equipment. However, the only character with this personal name and title is attested during the same period and geographical context as noted by Ranke.11 Here, a lady named Dimutshepenankh, whose outer and medium coffins are stored in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (CG 41060 and CG 41061), is given the “good name” of Tameramun (fig. 22-11). Furthermore, she also bears the same title of “Singer of the Inner of Amun”.12 This woman, who was buried at Deir el-Bahari, was the daughter of a High Priest of Montu Nesnebnetjerw. Her mummy and the inner coffin are believed lost, with no mention of them being made by Gauthier.

In comparing the dimensions of the medium coffin in Cairo with the one from Varese, it is clear that the latter could easily fit within the case of the former. For this reason, we can suppose that the Varese specimen may in fact be the inner coffin of the Cairo set belonging to Dimutshepenankh, thus confirming a later Kushite dating. Unfortunately the Pogliaghi’s ar-chives, now stored at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, do not provide any de-tails as to how or when the inner coffin arrived in his collection or to any connection between the three coffins now housed in Cairo and Varese.

The second phase of our research, which we aim to achieve in the next few years, consists of a restoration project that could allow for a scientific evaluation of the general state of the coffin. This will include a thorough cleaning of the surfaces, a chemical analysis of the black samples taken

11 PN I, 357. 12 Gauthier 1913, II, 363–381.

The Inner Coffin of Tameramun 451

from the interior of the case, and a reconstruction of the lost parts of the coffin with the aim of providing a new and valuing display.

Fig. 22-11. Dimutshepenankh, whose “good name” is Tameramun. Cairo

CG 41060 (after Gauthier 1913 II, pl. XXVI).

452 Chapter Twenty-two Bibliography Amann, Anne-Marie. 1983. “Zur anthropomorphisierten Vorstellung des

Djed-Pfeilers als Form des Osiris.” WeltOr 14: 46–62. Gauthier, Henri. 1913. Cercueils anthropoïdes des prêtres de Montou (CG

41042–41072). 2 vols. CGC. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

Taylor, John H. 2003. “Theban Coffins from the Twenty-second to the Twenty-sixth Dynasty: Dating and Synthesis of Development.” In The Theban Necropolis. Past, Present and Future, eds. Nigel C. Strudwick, and John H. Taylor, 95–121. London: British Museum Press.

———. 2006. “The Coffin of Padiashaikhet.” In Egyptian Art in the Ni-cholson Museum, Sydney, eds. Karin N. Sowada, and Boyo G. Ock-inga, 263‒291. Sydney: Meditarch.

Teeter, Emily, and Janet H. Johnson. eds. 2009. The Life of Meresamun. A Temple Singer in Ancient Egypt. Oriental Institute Museum Publica-tions 29. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Yoyotte, Jean. 1961. “Les vierges consacrées d’Amon thébain.” CRAIBL 105, 1: 43–52.