Article About Schostakovich Sonata

description

Transcript of Article About Schostakovich Sonata

Sonata No. 1 for Piano, Op. 12 by D. ShostakovichReview by: I. K.Music & Letters, Vol. 29, No. 3 (Jul., 1948), pp. 319-320Published by: Oxford University PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/729610 .Accessed: 14/09/2012 15:47

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Music &Letters.

http://www.jstor.org

REVIEWS OF MUSIC REVIEWS OF MUSIC REVIEWS OF MUSIC REVIEWS OF MUSIC REVIEWS OF MUSIC

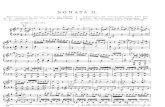

And so on, with never a hint that we could or should do anything about it. The words are set with the utmost efficiency and ruthlessness; the studied angularity leaves nothing lacking from this point of view. Neither is there a trace of tenderness in the very difficult ' Ballade'. It shows a formidable technique of construction, but what else can one say ? To play it at speed would take months of patient work and one doubts whether even its composer was capable of aurally imagining its sound at the speed at which he has marked it. Both works probably needed "getting off one's chest ", much as petulant rude letters get written-but not posted. I. K.

Searle, Humphrey, Concerto in D minor for Piano and Orchestra. (Lengnick, London.) Score for 2 Pianos, 6s.

The romantic bravura writing of Liszt seems to have haunted the composer in this work, at any rate in the first movement, which is never- theless entirely acceptable as a piece in its own right. The second move- ment is a chaconne proving the composer's ability in dealing with a problem of form. But it is the last movement, at first disconcerting because of the seeming conflict of styles, that is really the most interesting. Here, in the fugal episodes, a new spirit breaks through, and one is aware of a certain vigour and wildness admirably controlled and suggesting a much more individual personality. This Concerto is clearly a work of transition, not only showing the composer's allegiances but hinting, in the finale, at where he is going and what may be confidently expected of him. E. L.

Searle, Humphrey, Night Music for Chamber Orchestra, Op. 2. (Joseph Williams, London.) Full Score, Ios.

Mr. Searle has obviously been tempted in this youthful work to emulate some of the Schoenbergian processes of orchestration. The violin solo answered by the trombone followed by a horn solo and leading then to two isolated pzzzicato notes on the viola is an example of this kind of wilful disintegration of the orchestra. Much of the writing is contrapuntal, with canons and inversions galore. All of which is an indication of the musical school to which the composer has elected to belong and where he is attempting to hammer out a style of his own.

E. L.

Seiber, Matyis, Four Greek Folk Songs for Voice and Piano. (English Words by Peter Carroll.) (Boosey & Hawkes, London.) 5s.

Mr. Seiber is discreet, serviceable and artistic in the accompaniments he provides for these folksongs. Keeping to their spirit, he adds the minimum of embellishments. These tastefully thought-out accompani- ments show how folksongs may be satisfactorily harmonized without either pandering to their naivety or distorting them beyond recognition.

E. L.

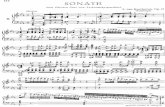

Shostakovich, D., Sonata Xo. i for Piano, Op. I2. (Anglo-Soviet Music Press, London.) 5s.

One comes away from a session with this work guiltily echoing recent pronouncements from the U.S.S.R. on its composers. This work, if its opus number is reliable, was written shortly after the delightful first

And so on, with never a hint that we could or should do anything about it. The words are set with the utmost efficiency and ruthlessness; the studied angularity leaves nothing lacking from this point of view. Neither is there a trace of tenderness in the very difficult ' Ballade'. It shows a formidable technique of construction, but what else can one say ? To play it at speed would take months of patient work and one doubts whether even its composer was capable of aurally imagining its sound at the speed at which he has marked it. Both works probably needed "getting off one's chest ", much as petulant rude letters get written-but not posted. I. K.

Searle, Humphrey, Concerto in D minor for Piano and Orchestra. (Lengnick, London.) Score for 2 Pianos, 6s.

The romantic bravura writing of Liszt seems to have haunted the composer in this work, at any rate in the first movement, which is never- theless entirely acceptable as a piece in its own right. The second move- ment is a chaconne proving the composer's ability in dealing with a problem of form. But it is the last movement, at first disconcerting because of the seeming conflict of styles, that is really the most interesting. Here, in the fugal episodes, a new spirit breaks through, and one is aware of a certain vigour and wildness admirably controlled and suggesting a much more individual personality. This Concerto is clearly a work of transition, not only showing the composer's allegiances but hinting, in the finale, at where he is going and what may be confidently expected of him. E. L.

Searle, Humphrey, Night Music for Chamber Orchestra, Op. 2. (Joseph Williams, London.) Full Score, Ios.

Mr. Searle has obviously been tempted in this youthful work to emulate some of the Schoenbergian processes of orchestration. The violin solo answered by the trombone followed by a horn solo and leading then to two isolated pzzzicato notes on the viola is an example of this kind of wilful disintegration of the orchestra. Much of the writing is contrapuntal, with canons and inversions galore. All of which is an indication of the musical school to which the composer has elected to belong and where he is attempting to hammer out a style of his own.

E. L.

Seiber, Matyis, Four Greek Folk Songs for Voice and Piano. (English Words by Peter Carroll.) (Boosey & Hawkes, London.) 5s.

Mr. Seiber is discreet, serviceable and artistic in the accompaniments he provides for these folksongs. Keeping to their spirit, he adds the minimum of embellishments. These tastefully thought-out accompani- ments show how folksongs may be satisfactorily harmonized without either pandering to their naivety or distorting them beyond recognition.

E. L.

Shostakovich, D., Sonata Xo. i for Piano, Op. I2. (Anglo-Soviet Music Press, London.) 5s.

One comes away from a session with this work guiltily echoing recent pronouncements from the U.S.S.R. on its composers. This work, if its opus number is reliable, was written shortly after the delightful first

And so on, with never a hint that we could or should do anything about it. The words are set with the utmost efficiency and ruthlessness; the studied angularity leaves nothing lacking from this point of view. Neither is there a trace of tenderness in the very difficult ' Ballade'. It shows a formidable technique of construction, but what else can one say ? To play it at speed would take months of patient work and one doubts whether even its composer was capable of aurally imagining its sound at the speed at which he has marked it. Both works probably needed "getting off one's chest ", much as petulant rude letters get written-but not posted. I. K.

Searle, Humphrey, Concerto in D minor for Piano and Orchestra. (Lengnick, London.) Score for 2 Pianos, 6s.

The romantic bravura writing of Liszt seems to have haunted the composer in this work, at any rate in the first movement, which is never- theless entirely acceptable as a piece in its own right. The second move- ment is a chaconne proving the composer's ability in dealing with a problem of form. But it is the last movement, at first disconcerting because of the seeming conflict of styles, that is really the most interesting. Here, in the fugal episodes, a new spirit breaks through, and one is aware of a certain vigour and wildness admirably controlled and suggesting a much more individual personality. This Concerto is clearly a work of transition, not only showing the composer's allegiances but hinting, in the finale, at where he is going and what may be confidently expected of him. E. L.

Searle, Humphrey, Night Music for Chamber Orchestra, Op. 2. (Joseph Williams, London.) Full Score, Ios.

Mr. Searle has obviously been tempted in this youthful work to emulate some of the Schoenbergian processes of orchestration. The violin solo answered by the trombone followed by a horn solo and leading then to two isolated pzzzicato notes on the viola is an example of this kind of wilful disintegration of the orchestra. Much of the writing is contrapuntal, with canons and inversions galore. All of which is an indication of the musical school to which the composer has elected to belong and where he is attempting to hammer out a style of his own.

E. L.

Seiber, Matyis, Four Greek Folk Songs for Voice and Piano. (English Words by Peter Carroll.) (Boosey & Hawkes, London.) 5s.

Mr. Seiber is discreet, serviceable and artistic in the accompaniments he provides for these folksongs. Keeping to their spirit, he adds the minimum of embellishments. These tastefully thought-out accompani- ments show how folksongs may be satisfactorily harmonized without either pandering to their naivety or distorting them beyond recognition.

E. L.

Shostakovich, D., Sonata Xo. i for Piano, Op. I2. (Anglo-Soviet Music Press, London.) 5s.

One comes away from a session with this work guiltily echoing recent pronouncements from the U.S.S.R. on its composers. This work, if its opus number is reliable, was written shortly after the delightful first

And so on, with never a hint that we could or should do anything about it. The words are set with the utmost efficiency and ruthlessness; the studied angularity leaves nothing lacking from this point of view. Neither is there a trace of tenderness in the very difficult ' Ballade'. It shows a formidable technique of construction, but what else can one say ? To play it at speed would take months of patient work and one doubts whether even its composer was capable of aurally imagining its sound at the speed at which he has marked it. Both works probably needed "getting off one's chest ", much as petulant rude letters get written-but not posted. I. K.

Searle, Humphrey, Concerto in D minor for Piano and Orchestra. (Lengnick, London.) Score for 2 Pianos, 6s.

The romantic bravura writing of Liszt seems to have haunted the composer in this work, at any rate in the first movement, which is never- theless entirely acceptable as a piece in its own right. The second move- ment is a chaconne proving the composer's ability in dealing with a problem of form. But it is the last movement, at first disconcerting because of the seeming conflict of styles, that is really the most interesting. Here, in the fugal episodes, a new spirit breaks through, and one is aware of a certain vigour and wildness admirably controlled and suggesting a much more individual personality. This Concerto is clearly a work of transition, not only showing the composer's allegiances but hinting, in the finale, at where he is going and what may be confidently expected of him. E. L.

Searle, Humphrey, Night Music for Chamber Orchestra, Op. 2. (Joseph Williams, London.) Full Score, Ios.

Mr. Searle has obviously been tempted in this youthful work to emulate some of the Schoenbergian processes of orchestration. The violin solo answered by the trombone followed by a horn solo and leading then to two isolated pzzzicato notes on the viola is an example of this kind of wilful disintegration of the orchestra. Much of the writing is contrapuntal, with canons and inversions galore. All of which is an indication of the musical school to which the composer has elected to belong and where he is attempting to hammer out a style of his own.

E. L.

Seiber, Matyis, Four Greek Folk Songs for Voice and Piano. (English Words by Peter Carroll.) (Boosey & Hawkes, London.) 5s.

Mr. Seiber is discreet, serviceable and artistic in the accompaniments he provides for these folksongs. Keeping to their spirit, he adds the minimum of embellishments. These tastefully thought-out accompani- ments show how folksongs may be satisfactorily harmonized without either pandering to their naivety or distorting them beyond recognition.

E. L.

Shostakovich, D., Sonata Xo. i for Piano, Op. I2. (Anglo-Soviet Music Press, London.) 5s.

One comes away from a session with this work guiltily echoing recent pronouncements from the U.S.S.R. on its composers. This work, if its opus number is reliable, was written shortly after the delightful first

And so on, with never a hint that we could or should do anything about it. The words are set with the utmost efficiency and ruthlessness; the studied angularity leaves nothing lacking from this point of view. Neither is there a trace of tenderness in the very difficult ' Ballade'. It shows a formidable technique of construction, but what else can one say ? To play it at speed would take months of patient work and one doubts whether even its composer was capable of aurally imagining its sound at the speed at which he has marked it. Both works probably needed "getting off one's chest ", much as petulant rude letters get written-but not posted. I. K.

Searle, Humphrey, Concerto in D minor for Piano and Orchestra. (Lengnick, London.) Score for 2 Pianos, 6s.

The romantic bravura writing of Liszt seems to have haunted the composer in this work, at any rate in the first movement, which is never- theless entirely acceptable as a piece in its own right. The second move- ment is a chaconne proving the composer's ability in dealing with a problem of form. But it is the last movement, at first disconcerting because of the seeming conflict of styles, that is really the most interesting. Here, in the fugal episodes, a new spirit breaks through, and one is aware of a certain vigour and wildness admirably controlled and suggesting a much more individual personality. This Concerto is clearly a work of transition, not only showing the composer's allegiances but hinting, in the finale, at where he is going and what may be confidently expected of him. E. L.

Searle, Humphrey, Night Music for Chamber Orchestra, Op. 2. (Joseph Williams, London.) Full Score, Ios.

Mr. Searle has obviously been tempted in this youthful work to emulate some of the Schoenbergian processes of orchestration. The violin solo answered by the trombone followed by a horn solo and leading then to two isolated pzzzicato notes on the viola is an example of this kind of wilful disintegration of the orchestra. Much of the writing is contrapuntal, with canons and inversions galore. All of which is an indication of the musical school to which the composer has elected to belong and where he is attempting to hammer out a style of his own.

E. L.

Seiber, Matyis, Four Greek Folk Songs for Voice and Piano. (English Words by Peter Carroll.) (Boosey & Hawkes, London.) 5s.

Mr. Seiber is discreet, serviceable and artistic in the accompaniments he provides for these folksongs. Keeping to their spirit, he adds the minimum of embellishments. These tastefully thought-out accompani- ments show how folksongs may be satisfactorily harmonized without either pandering to their naivety or distorting them beyond recognition.

E. L.

Shostakovich, D., Sonata Xo. i for Piano, Op. I2. (Anglo-Soviet Music Press, London.) 5s.

One comes away from a session with this work guiltily echoing recent pronouncements from the U.S.S.R. on its composers. This work, if its opus number is reliable, was written shortly after the delightful first

319 319 319 319 319

MUSIC AND LETTERS MUSIC AND LETTERS MUSIC AND LETTERS MUSIC AND LETTERS MUSIC AND LETTERS

Symphony, in comparison with which it is poverty-stricken not only in its invention but in its treatment of the medium. It is common know- ledge that the piano is initially a percussion instrument, but all the great composers and interpreters have had a fair success at disguising this for some time now. Of the twenty-one pages of this single-movement Sonata no less than seventeen require martellato or at least semi-staccato playing of unrelenting dissonance. The music is built up by mechanical development of short ideas which, shorn of trimming, are commonplace if not vulgar. The work is considerably more difficult than Beethoven's Op. Io6. I. K.

Stevens, Bernard, Ricercar for String Orchestra. (Lengnick, London.) Full Score, 4s.

Grove (I908) calls Ricercare "an Italian term of the I7th century, signifying a fugue of the closest and most learned description ". This work has every right to such a definition, badly though it fits its purpose in the Dictionary. In its twelve minutes it introduces three subjects in succession, each worked in strictest fugue with two counter-subjects and each treated with the utmost resource of contrapuntal device, with a combination of all three as the splendidly sonorous and inevitable climax. Although the utmost freedom of modulation is used, there are no loose ends of unresolved or illogical progression.

All the foregoing is in a sense a description of the piece, and one hastens to pay tribute to a real contrapuntal technique which shows up the slipshod methods of the nothing-barred school. But such praise might be a positive disservice to the composer, did one not insist that the work is deeply felt and musically moving and convincing. The string writing is resourceful, but not difficult. I. K.

Szervansky, Endre, Sonatina for Piano. (Cserepfalvi, Budapest.) This short work, composed in I94I, is a delightful example of clear

piano-writing making use of the kind of Slav themes which have become familiar to us through the work of Kodaly and Bart6k. The composer has given us a Sonatina that has none of the technical difficulty of, say, Bart6k's work, while fulfilling the spirit of it. In short, it is to be recom- mended both on its own merits and as a charming introduction to the Central-European folk-music composers. K. A.

Tate, Phyllis, The Quiet Mind for Voice and Piano. (Words ascribed to Sir Edward Dyer.) (Oxford University Press.) 3s.

Miss Tate has a poetic sense of humour. Her way of reflecting the poem's tranquil sense of resignation is entirely appropriate. She has been able to add point to the amusing lines sometimes by an unexpected rhythm, but generally by finding a beautiful vocal equivalent of the verbal inflections. A charming fancy of a song that a singer will love to have by him. E. L.

Tate, Phyllis, Epitaph for Voice and Piano (Sir Walter Raleigh). (Oxford University Press.) 3s.

The slowly moving harmonies of the -piano's chords pass like a pro- cession beneath an expressive declamatory vocal line. There is a fine climax to a simple and wholly successful short song. I. K.

Symphony, in comparison with which it is poverty-stricken not only in its invention but in its treatment of the medium. It is common know- ledge that the piano is initially a percussion instrument, but all the great composers and interpreters have had a fair success at disguising this for some time now. Of the twenty-one pages of this single-movement Sonata no less than seventeen require martellato or at least semi-staccato playing of unrelenting dissonance. The music is built up by mechanical development of short ideas which, shorn of trimming, are commonplace if not vulgar. The work is considerably more difficult than Beethoven's Op. Io6. I. K.

Stevens, Bernard, Ricercar for String Orchestra. (Lengnick, London.) Full Score, 4s.

Grove (I908) calls Ricercare "an Italian term of the I7th century, signifying a fugue of the closest and most learned description ". This work has every right to such a definition, badly though it fits its purpose in the Dictionary. In its twelve minutes it introduces three subjects in succession, each worked in strictest fugue with two counter-subjects and each treated with the utmost resource of contrapuntal device, with a combination of all three as the splendidly sonorous and inevitable climax. Although the utmost freedom of modulation is used, there are no loose ends of unresolved or illogical progression.

All the foregoing is in a sense a description of the piece, and one hastens to pay tribute to a real contrapuntal technique which shows up the slipshod methods of the nothing-barred school. But such praise might be a positive disservice to the composer, did one not insist that the work is deeply felt and musically moving and convincing. The string writing is resourceful, but not difficult. I. K.

Szervansky, Endre, Sonatina for Piano. (Cserepfalvi, Budapest.) This short work, composed in I94I, is a delightful example of clear

piano-writing making use of the kind of Slav themes which have become familiar to us through the work of Kodaly and Bart6k. The composer has given us a Sonatina that has none of the technical difficulty of, say, Bart6k's work, while fulfilling the spirit of it. In short, it is to be recom- mended both on its own merits and as a charming introduction to the Central-European folk-music composers. K. A.

Tate, Phyllis, The Quiet Mind for Voice and Piano. (Words ascribed to Sir Edward Dyer.) (Oxford University Press.) 3s.

Miss Tate has a poetic sense of humour. Her way of reflecting the poem's tranquil sense of resignation is entirely appropriate. She has been able to add point to the amusing lines sometimes by an unexpected rhythm, but generally by finding a beautiful vocal equivalent of the verbal inflections. A charming fancy of a song that a singer will love to have by him. E. L.

Tate, Phyllis, Epitaph for Voice and Piano (Sir Walter Raleigh). (Oxford University Press.) 3s.

The slowly moving harmonies of the -piano's chords pass like a pro- cession beneath an expressive declamatory vocal line. There is a fine climax to a simple and wholly successful short song. I. K.

Symphony, in comparison with which it is poverty-stricken not only in its invention but in its treatment of the medium. It is common know- ledge that the piano is initially a percussion instrument, but all the great composers and interpreters have had a fair success at disguising this for some time now. Of the twenty-one pages of this single-movement Sonata no less than seventeen require martellato or at least semi-staccato playing of unrelenting dissonance. The music is built up by mechanical development of short ideas which, shorn of trimming, are commonplace if not vulgar. The work is considerably more difficult than Beethoven's Op. Io6. I. K.

Stevens, Bernard, Ricercar for String Orchestra. (Lengnick, London.) Full Score, 4s.

Grove (I908) calls Ricercare "an Italian term of the I7th century, signifying a fugue of the closest and most learned description ". This work has every right to such a definition, badly though it fits its purpose in the Dictionary. In its twelve minutes it introduces three subjects in succession, each worked in strictest fugue with two counter-subjects and each treated with the utmost resource of contrapuntal device, with a combination of all three as the splendidly sonorous and inevitable climax. Although the utmost freedom of modulation is used, there are no loose ends of unresolved or illogical progression.

All the foregoing is in a sense a description of the piece, and one hastens to pay tribute to a real contrapuntal technique which shows up the slipshod methods of the nothing-barred school. But such praise might be a positive disservice to the composer, did one not insist that the work is deeply felt and musically moving and convincing. The string writing is resourceful, but not difficult. I. K.

Szervansky, Endre, Sonatina for Piano. (Cserepfalvi, Budapest.) This short work, composed in I94I, is a delightful example of clear

piano-writing making use of the kind of Slav themes which have become familiar to us through the work of Kodaly and Bart6k. The composer has given us a Sonatina that has none of the technical difficulty of, say, Bart6k's work, while fulfilling the spirit of it. In short, it is to be recom- mended both on its own merits and as a charming introduction to the Central-European folk-music composers. K. A.

Tate, Phyllis, The Quiet Mind for Voice and Piano. (Words ascribed to Sir Edward Dyer.) (Oxford University Press.) 3s.

Miss Tate has a poetic sense of humour. Her way of reflecting the poem's tranquil sense of resignation is entirely appropriate. She has been able to add point to the amusing lines sometimes by an unexpected rhythm, but generally by finding a beautiful vocal equivalent of the verbal inflections. A charming fancy of a song that a singer will love to have by him. E. L.

Tate, Phyllis, Epitaph for Voice and Piano (Sir Walter Raleigh). (Oxford University Press.) 3s.

The slowly moving harmonies of the -piano's chords pass like a pro- cession beneath an expressive declamatory vocal line. There is a fine climax to a simple and wholly successful short song. I. K.

Symphony, in comparison with which it is poverty-stricken not only in its invention but in its treatment of the medium. It is common know- ledge that the piano is initially a percussion instrument, but all the great composers and interpreters have had a fair success at disguising this for some time now. Of the twenty-one pages of this single-movement Sonata no less than seventeen require martellato or at least semi-staccato playing of unrelenting dissonance. The music is built up by mechanical development of short ideas which, shorn of trimming, are commonplace if not vulgar. The work is considerably more difficult than Beethoven's Op. Io6. I. K.

Stevens, Bernard, Ricercar for String Orchestra. (Lengnick, London.) Full Score, 4s.

Grove (I908) calls Ricercare "an Italian term of the I7th century, signifying a fugue of the closest and most learned description ". This work has every right to such a definition, badly though it fits its purpose in the Dictionary. In its twelve minutes it introduces three subjects in succession, each worked in strictest fugue with two counter-subjects and each treated with the utmost resource of contrapuntal device, with a combination of all three as the splendidly sonorous and inevitable climax. Although the utmost freedom of modulation is used, there are no loose ends of unresolved or illogical progression.

All the foregoing is in a sense a description of the piece, and one hastens to pay tribute to a real contrapuntal technique which shows up the slipshod methods of the nothing-barred school. But such praise might be a positive disservice to the composer, did one not insist that the work is deeply felt and musically moving and convincing. The string writing is resourceful, but not difficult. I. K.

Szervansky, Endre, Sonatina for Piano. (Cserepfalvi, Budapest.) This short work, composed in I94I, is a delightful example of clear

piano-writing making use of the kind of Slav themes which have become familiar to us through the work of Kodaly and Bart6k. The composer has given us a Sonatina that has none of the technical difficulty of, say, Bart6k's work, while fulfilling the spirit of it. In short, it is to be recom- mended both on its own merits and as a charming introduction to the Central-European folk-music composers. K. A.

Tate, Phyllis, The Quiet Mind for Voice and Piano. (Words ascribed to Sir Edward Dyer.) (Oxford University Press.) 3s.

Miss Tate has a poetic sense of humour. Her way of reflecting the poem's tranquil sense of resignation is entirely appropriate. She has been able to add point to the amusing lines sometimes by an unexpected rhythm, but generally by finding a beautiful vocal equivalent of the verbal inflections. A charming fancy of a song that a singer will love to have by him. E. L.

Tate, Phyllis, Epitaph for Voice and Piano (Sir Walter Raleigh). (Oxford University Press.) 3s.

The slowly moving harmonies of the -piano's chords pass like a pro- cession beneath an expressive declamatory vocal line. There is a fine climax to a simple and wholly successful short song. I. K.

Symphony, in comparison with which it is poverty-stricken not only in its invention but in its treatment of the medium. It is common know- ledge that the piano is initially a percussion instrument, but all the great composers and interpreters have had a fair success at disguising this for some time now. Of the twenty-one pages of this single-movement Sonata no less than seventeen require martellato or at least semi-staccato playing of unrelenting dissonance. The music is built up by mechanical development of short ideas which, shorn of trimming, are commonplace if not vulgar. The work is considerably more difficult than Beethoven's Op. Io6. I. K.

Stevens, Bernard, Ricercar for String Orchestra. (Lengnick, London.) Full Score, 4s.

Grove (I908) calls Ricercare "an Italian term of the I7th century, signifying a fugue of the closest and most learned description ". This work has every right to such a definition, badly though it fits its purpose in the Dictionary. In its twelve minutes it introduces three subjects in succession, each worked in strictest fugue with two counter-subjects and each treated with the utmost resource of contrapuntal device, with a combination of all three as the splendidly sonorous and inevitable climax. Although the utmost freedom of modulation is used, there are no loose ends of unresolved or illogical progression.

All the foregoing is in a sense a description of the piece, and one hastens to pay tribute to a real contrapuntal technique which shows up the slipshod methods of the nothing-barred school. But such praise might be a positive disservice to the composer, did one not insist that the work is deeply felt and musically moving and convincing. The string writing is resourceful, but not difficult. I. K.

Szervansky, Endre, Sonatina for Piano. (Cserepfalvi, Budapest.) This short work, composed in I94I, is a delightful example of clear

piano-writing making use of the kind of Slav themes which have become familiar to us through the work of Kodaly and Bart6k. The composer has given us a Sonatina that has none of the technical difficulty of, say, Bart6k's work, while fulfilling the spirit of it. In short, it is to be recom- mended both on its own merits and as a charming introduction to the Central-European folk-music composers. K. A.

Tate, Phyllis, The Quiet Mind for Voice and Piano. (Words ascribed to Sir Edward Dyer.) (Oxford University Press.) 3s.

Miss Tate has a poetic sense of humour. Her way of reflecting the poem's tranquil sense of resignation is entirely appropriate. She has been able to add point to the amusing lines sometimes by an unexpected rhythm, but generally by finding a beautiful vocal equivalent of the verbal inflections. A charming fancy of a song that a singer will love to have by him. E. L.

Tate, Phyllis, Epitaph for Voice and Piano (Sir Walter Raleigh). (Oxford University Press.) 3s.

The slowly moving harmonies of the -piano's chords pass like a pro- cession beneath an expressive declamatory vocal line. There is a fine climax to a simple and wholly successful short song. I. K.

320 320 320 320 320