Arnold VoterIgnorance

-

Upload

murilo-guimaraes -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

0

Transcript of Arnold VoterIgnorance

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

1/20

The electoral consequences of voter ignorance

Jason Ross ArnoldPolitical Science Program, L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, Virginia Commonwealth University, 923 W. Franklin Street, Box 842028,Richmond, VA 23284-2028, USA

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:Received 22 July 2011Received in revised form 3 June 2012Accepted 7 June 2012

Keywords:Political knowledgeVoter ignoranceVoting and electionsVoting behaviorLeft-wing parties

a b s t r a c t

A great deal of research has suggested that scholarly and popular concerns about lowlevelsof citizen political knowledge are exaggerated. One implication of that research is thatpolitical history would have unfolded just as it did even if electorates had been morepolitically informed. This paper presents evidence that counters these claims, showing aninfusion of electorally relevant information in twenty-seven democracies would havelikely led to a lot of vote switching , ultimately changing the composition of manygovernments. The paper also directly and systematically examines what we might call the enlightened natural constituency hypothesis, which expects lower-income citizens tovote disproportionately for left parties once armed with more political knowledge. Whilethe basic argument about how political ignorance disproportionately affects the left snatural constituency is not new, the hypothesis has thus far not been tested. The analysisprovides provisional support for the hypothesis.

2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

A half century of evidence shows what democratictheorists long suspected very low levels of citizenknowledge about politics. Survey after survey in the U.S.and beyond illustrates that citizens often do not under-stand what their representatives stand for, or what theyhave done in of ce. These routine failures of citizenmonitoring and selection frustrate representative democ-racy s most basic processes.

Not all theorists conclude from the dismaying survey

evidence that less informed voters have a more dif culttime understanding party differences or making choicesthat re ect their preferences. Some discount voters lack of knowledge and argue voters can do well enough in elec-tions by following cues from trusted, better informedindividuals and groups (e.g. party leaders, interest groups,friends in social networks) (e.g. Lupia, 1994 ). Others arguevoter errors are indeed pervasive, but across populationsthey are random and offsetting, so when viewed as

a collective, electorates behave as if rational ( Page andShapiro, 1992 ).

Ultimately, the question of whether widespread publicignorance imperils representative democracy turns on twocritical empirical questions. First, do very similar individ-uals who differ only in their political knowledge still onaverage vote identically? If information shortcuts (i.e. cues)work as advertised, these differences should be slight.Second, would electorates make different collective choicesif voter ignorance was not as widespread a problem? If lowlevels of political knowledge were simply an exaggerated

concern, as some theorists contend, we would expectpolitical history to unfold as it has even if citizens broughtmore civics knowledge to the polls.

In this paper I address both questions, each of whichtackles the counterfactual question at the heart of thedebate: would voters choose differently if they had moreinformation? I rst evaluate existing research on howpolitical knowledge or the lack thereof affects votingbehavior. Second, I estimate the extent to which voters intwenty-seven democracies would have changed theirminds at the ballot box if they had additional electorallyrelevant political information. Third, I examine the politicalE-mail address: [email protected] .

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Electoral Studies

j ou rna l homepage : www.e l sev ie r. com/ loca te / e l ec t s tud

0261-3794/$

see front matter

2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.06.003

Electoral Studies 31 (2012) 796 815

mailto:[email protected]://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/02613794http://www.elsevier.com/locate/electstudhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.06.003http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.06.003http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.06.003http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.06.003http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.06.003http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.06.003http://www.elsevier.com/locate/electstudhttp://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/02613794mailto:[email protected] -

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

2/20

implications of these information effects, speci callywhether left parties would have enjoyed increased supportif voters were better informed. While the evidence is clearthat relatively poorer citizens for some, left parties natural constituency tend to have lower levels of political knowledge, scholars have only speculated aboutwhether these individuals would increase their support forleft parties if they were better informed.

2. The role of political knowledge in voting behavior

Until recently, the conventional wisdom in democratictheory viewed widespread voter ignorance as generallybadfor democracy. The consequences seemed clear: voters whowent to the polls uninformed about candidates and theirprograms were more likely to make inept choices that is,contrary to their preferences and interests. Voters whowere unaware of elected politicians performance in of cewere also seen as less prepared to sanction waywardrepresentatives. Moreover, politicians who were aware of constituents ignorance had less reason to fear electoralsanctioning, giving them freer rein to stray from electoralmandates and public opinion. Overall, for many democratictheorists, widespread public ignorance indicated a failureof the republican model in contemporary practice (e.g.Schumpeter, 1942; Somin, 1998 ).

Theorists, however, have not been uniformly pessimisticabout low levels of knowledge observed in surveys. Downs(1957) , for instance, presented a model of voting behaviorthat accepted citizens rational ignorance as a naturalconsequence of the relatively high cost of obtaining polit-ical information. Instead of decrying their lack of knowl-edge, Downs claimed that voters rationally rely oninformation shortcuts, namely cues from trusted elitesabout parties policy positions. By using these shortcuts,voters could pass on their information costs to others whocould more ef ciently obtain relevant knowledge. 1

Numerous scholars since Downs have adopted the coun-terintuitive position that voter ignorance is not a problemfor democracy due to the way voters rely on cues frommore knowledgeable elites and discussion partners (e.g.Popkin, 1991; Sniderman et al., 1991 ).2 Other theoristscautioned against making inferences about citizencompetence from surveys, due to well-known, possiblyinsurmountable problems of measurement, reliability, andvalidity. 3 For instance, they questioned whether a series of survey questions (e.g. Who is the Vice-President? ) reallymeasures the extent of citizens political learning andreasoning capabilities. Overall, those following Downs andother early cue-taking theorists (e.g. Berelson et al., 1954 )

conclude voters can make reasonable choices (i.e. votesre ect preferences) without appearing well-informedabout politics on surveys.

There are several reasons to be skeptical about theoptimistic conclusions arising from the concept of lowinformation rationality . First, there is the questionableproposition that individuals at different knowledge levelsuse cues equally well (e.g. Lau and Redlawsk, 2001 ).4

Second, along with the ways individuals pro tably useinformation shortcuts, there are many negative biasesassociated with cue-taking that cause individuals tomake predictable logical mistakes ( Kuklinski and Quirk,2000 ).

Third, aside from notable exceptions (e.g. Lupia, 1994 ),the cue-taking model has little empirical support outsideof laboratory experiments modeled on the American two-party presidential system. 5 For those interested in devel-oping a more widely applicable democratic theory, theexperiments lack external validity. For example, can votersin multi-party systems utilize cues with the same ease andef ciency as voters in two-party systems? While institu-tions associated with multi-party systems do offer citizenssome information advantages ( Gordon and Segura, 1997;Arnold, 2008 ), these party systems also tend to make thevote choice more complicated. High-information voters inthese contexts bene t from the additional choices, butlow-information voters face a more confusing array of options and as a consequence often choose not to vote( Jusko and Shively, 2005 ).6 Thus, while informationshortfalls might be more easily overcome in stable two-party systems, we have reason to believe that navigatingmulti-party systems using cues might be a more dif culttask. Overall, existing research about voter ignoranceunfortunately offers few insights about the extent towhich information matters across the wide range of political institutions and political cultures in the world sdemocracies, not to mention their varied levels of politicaland economic development.

2.1. Should we be optimistic about rational publics ?

Another departure from the more conventional view of public ignorance considers electorates as rational, collec-tive decision-making bodies, akin to Condorcet s jury

1 Though previous scholars had introduced the concept of cue-takingin voting models Berelson et al. (1954) had noted the tendency of less informed voters to follow opinion leaders Downs s more explicitformulation has remained the most prominent.

2 Popkin (1991) , for example, argued that voters use heuristics and gutlevel reasoning (or low information rationality ) based on elite cues andlife experiences to make rational political choices that correctly expresstheir preferences.

3

See Lupia and McCubbins (1998); Rahn et al. (1994); Zaller (1992) ;and Zaller and Feldman (1992) . See also Piazza et al. (1989) .

4 Sniderman has acknowledged this as a problem for the cue-takingmodel ( 2000 : 72). In particular, Lau and Redlawsk (2001) found howeffectively individuals used cues and cognitive heuristics depended ontheir level of political knowledge. Instead of equalizing rational decision-making, cue usage reinforced a population s level of informationinequality. Plus, political knowledge was crucial in using cues effectively;uninformed individuals tended to make more errors in their inferences.

5 One reason non-experimental research has been so scarce is thattraditional methods of analyzing voting behavior do not lend themselveswell to testing the cue-taking hypothesis. For example, individuals onsurveys are not routinely asked where they obtain speci c pieces of information, and if they were, it is doubtful they would remember ( Lodgeet al., 1989; Zaller, 1992 ).

6 On the other hand, voters in two-party systems might have somedif culty distinguishing between two center-leaning parties, both of which are strategically ambiguous about policies during general election

contests. Downs, for example, identi ed politicians

incentives to becloud their policies in a fog of ambiguity .

J.R. Arnold / Electoral Studies 31 (2012) 796 815 797

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

3/20

theorem ( Page and Shapiro, 1992 ).7 This argumentcontends that although many citizens are not wellinformed about politics, an electorate as a group holdsreasonable and relatively stable preferences. 8 Focusingsolely on individuals ignores the emergent properties of polities, and when individuals attitudes are aggregated,individual-level random noise is eliminated through off-setting effects (14 15, 25). 9

However impressive the miracle of aggregation

appears, the assumption of mostly random errors has notsurvived subsequent analysis. Aggregation might cancelout some of the noise, but it does not eliminate systematic variation in political attitudes due to political knowledgeand other individual characteristics ( Althaus, 2003 ; Duchet al., 2000; Duch and Palmer, 2002; Krause, 1997 ). More-over, while the notion of offsetting effects is plausible in anevenly split two-party system like the U.S., where an erroron one side is mirrored by an error on the other, the model sapplicability for multiparty systems, where errors areunlikely as symmetrical, remains in question.

2.2. Political knowledge matters (Not here but there?)

The cue-taking and collective rationality argumentsboth discount the importance of political knowledge forvoting behavior. The discon rming evidence identi edabove (e.g. Lau and Redlawsk, 2001 ), however important,does not provide direct support for theories emphasizingpolitical knowledge. Recent work demonstrating a positiveconnection between information and voting, however, hasbegun to accumulate. What we have learned so far is thatAmerican voters with less political knowledge are lesslikely to recognize a suitable party or candidate given their

preferences ( Delli Carpini and Keeter, 1996 ). Moreover, each additional increment of knowledge tighten[s] theconnection between attitudes and the vote (256). Simi-larly, British voters who have more knowledge of partyplatforms tend to select parties that better re ect theirpolicy preferences ( Andersen et al., 2002, 2005 ).10

We also know that many voters would likely changetheir vote choices if they were better informed. Recall thequestion posed above: do very similar individuals whodiffer only in their measured levels of political knowledgestill on average vote identically? If information shortcuts(i.e. cues) work as theorized, these differences should beslight. Bartels (1996) addressed this question in the context

of American presidential elections and found unambiguousevidence showing voter ignorance signi cantly affectedvoting behavior. Large numbers of American voters inelections from 1972 to 1992 apparently would havechanged their minds had they been better informed.Contrary to predictions that behavioral errors from the lessinformed would cancel out due to offsetting effects (i.e. theerrors are random), the analysis found clear systematicbiases among the less informed (e.g. toward incumbentsand Democrats).

However remarkable the vote swings Bartels found atthe individual level changes ranged from 7.58% (in 1976)to 10.62% (in 1992) aggregate electoral shifts were lesssubstantial (0.35% in 1976 to 5.62 in 1980). 11 While politicalknowledge clearly affected individual vote choice in USpresidential elections, none of the vote swings would havechanged historical outcomes. That is, the netelectoral effectof increased information was smaller than the margin of victory ( Althaus, 2003 : 126). In sum, we are left with anemerging picture that political knowledge does affectvoting behavior; consequently, democratic theorists havereason to push back against writers discounting itsimportance. Still, existing research leaves us with theimpression that voter ignorance might not have any real-world political implications. Would different governmentshave been formed if electorates had been better informed?What kinds of historical patterns would have emerged if voters had the tools to more effectively connect theirpreferences with vote choices? One way to examine thepolitical implications of voter ignorance is to assesswhether any partisan or ideological biases result frominformation inequalities within societies.

3. The political implications of voter ignorance:effects on left voting

Theorists have long suspected that parties of the left areparticularly disadvantaged due to widespread voter igno-rance. Surprisingly, few have attempted to assess the extentto which the suspicion is true. Why would voter ignoranceweaken left parties more than those of the right or center?Why would left parties especially bene t from betterinformed electorates?

The argument many have made is two-fold (e.g.Converse, 1964; Delli Carpini and Keeter, 1996; Luskin,2002 : 298). First, less wealthy voters are left parties

natural constituency . Because left parties tend to offera more generous welfare state and more wealth redistri-bution than parties of the right and center, lower stratavoters would naturally prefer left governments thatpromise to improve their lot. The argument clearly employsa class-based voting model which assumes a voter s salientgroup identity and source of political preferences is orshould be her socioeconomic positions (see below) Thesecond part of the argument rests on reams of empiricalevidence showing income and other measures of

7 Page and Shapiro sum up Condorcet s main point this way (p. 26): if individuals have even a modest tendency to be correct, a collectivedecision by those individuals can have a very high likelihood of beingright. See also Grofman and Feld (1988) .

8 See Althaus (2003 : 30 35) for a review of the concept of collectiverationality.

9 While Page and Shapiro s focus was on policy preferences, there areno reasons why the hypothesized mechanism cannot be applied toelections.

10 Interestingly, voters values appear to interact with their informationlevels. Heath and Tilley (2003) , examining British Election Studies (BES)data from 1983 to 1997, found values signi cantly decreased the inde-pendent effect of information on vote choice. Information did, however,

strengthen the relationship between individuals

values and their votechoices.

11 Tka (2004) estimated these information effects in a wider set of

political contexts, nding clear shifts in voters

intentions, but like Bartels,relatively modest in the aggregate.

J.R. Arnold / Electoral Studies 31 (2012) 796 815798

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

4/20

socioeconomic status to be strong predictors of politicalknowledge (see below).

Taken together, these conjectures imply that lowerstrata voters are less likely to select candidates or partieswho will work on their behalf. Due to their lack of politicalknowledge, these voters cannot as easily discern parties

political orientations or understand their policy platforms,therefore making them less likely to support parties whore ect their preferences. In other words, citizens predis-posed to left voting who remain in the dark about, forexample, parties relative positions are more likely thantheir informed counterparts to mistakenly select a right-wing candidate. 12 If circumstances caused the informationgap to close, we would expect left parties to especiallybene t; that is, an in ux of electorally relevant politicalinformation would ow disproportionately to the left snatural constituency. We can call this the enlightenednatural constituency argument.

3.1. Why are poorer voters less informed?

While studies have repeatedly demonstrated a statisti-cally strong link between levels of income and politicalknowledge, there is no systematic research examining thereasons for the strong connection. Luskin s (1990) in u-ential typology focusing on the numerous factors thatshape citizens capabilities , opportunities , and motivations tolearn about politics remains a useful starting point. Forexample, many economically poor citizens lack the capacityto understand the complexities of the political world orremember key facts, simply due to their relatively disad-vantaged educational backgrounds and other products of a resource-poor upbringing. Features of the macro-political

environment, from the nature of a country s mass mediasystem to its political institutions, also shape citizens

motivations and opportunities to acquire political informa-tion. There is disagreement, as noted above, about theextent to which some institutions (e.g. proportionalrepresentation electoral rules) offer citizens informationaladvantages ( Gordon and Segura, 1997; Jusko and Shively,2005; Arnold, 2008 ).

Marxian political theorists might add to the discussionby pointing out that the poor tend to have jobs with verylow pay, autonomy, and creativity, leading them to frus-tration, fatalism, and apathy. Why bother making efforts tolearn about politics if little can be done to improve the

status quo (or so it might seem)? A related argument wouldemphasize that the poor are typically too busy workingexhausting, often hazardous jobs, just to pay the bills,leaving little time and energy to spare for politics. Anespecially ground-down, fatalistic, distracted group wouldcertainly have fewer capabilities (in this context, time,energy, attention, and/or hope), opportunities, and moti-vations to acquire political information.

A different sort of motivation-based argument mighthighlight the decreasing relevance of explicitly class-

oriented electoral politics at least in party platforms andin national political rhetoric due to the so-called post-materialist turn, leaving many issues the poor might favorincreasingly off the political agenda. That argument, whichone might nd within the debate about the so-called end toclass politics , has limited use here for two reasons. 13 First,the endof class politics debate focuseson electoral changesinpost-industrialized democracies,whilethis paperanalyzesa broader set of cases. Second, the link between income andpolitical knowledge existed before and after the onset of post-materialism (e.g. Converse, 1964; Tichenor et al., 1970;Delli Carpini and Keeter, 1996; Bennett et al., 1996;Grnlund and Milner, 2006 ). Overall, while we have abun-dant over-time evidence linking income to political knowl-edge, and there are many plausible mechanisms linkingrelative poverty and political ignorance, more systematicresearch is needed to examine the connection.

3.2. Why would poorer voters choose left parties?

Once poorer voters became better informed, why wouldthey be more likely to choose left parties? Although leftparties vary within and across countries, they tend to sharethe common goals of increasing social equality, remedyingmarket failures, and promoting (downwardly owing)redistributive policies (see, e.g. Cronin et al., 2011; Levitskyand Roberts, 2011 : 5). These kinds of commitments existeven in cases where center-left parties have embracedelements of neoliberalism. For instance, (New) Labour inthe U.K. and the Democratic Party in the U.S., despite theircentripetal tendencies toward the ideological center, haveremained relatively more supportive of redistribution andsocial safety nets compared with their conservative oppo-nents, even if their equity commitments are increasinglyexpressed in defensive postures that is, defending thewelfare state status quo against right-wing retrenchmentattempts (e.g. U.S. Democrats defense of Social Securityafter President George W. Bush sought partial privatizationin 2005). In these and other cases, well informed voterswould know that it is typically left parties who promise(and sometimes even deliver) policies promoting down-ward redistribution and greater social equality. Very wellinformed voters in the U.S. would know the DemocraticParty is less likely than the Republican Party to cut or gutprograms like Social Security, and more likely to try toincrease unemployment insurance and governmentsupport for health care. In the U.K., well informed voterswould know Labour is less likely than the Conservatives topromote austerity, at least when education, health care, orother welfare programs are targeted. While center-leftparties social equity goals might sometimes be couchedin capitalist language e.g. programs that aim to build human capital the idea still is to promote state-fundedopportunities that, in their best manifestations,

12 There is also of course the false consciousness argument prominent

in Marxist political theory. A more contemporary argument along thesame lines is Frank (2005) . See also Bartels s (2006) critique.

13 Despite con dent claims by analysts about the decline of class-basedvoting, especially in Western Europe, the jury is still out on the matter.For arguments supporting the decline theory, see Franklin et al., (1992);

Nieuwbeerta and de Graaf (1999) . For arguments critical of decline, seeBartels (2006); Elff (2007); Evans (2000); Manza et al. (1995) .

J.R. Arnold / Electoral Studies 31 (2012) 796 815 799

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

5/20

disproportionately bene t the disadvantaged (althougheveryone arguably bene ts, even if indirectly). Left andcenter-left parties greater relative commitment to redistri-bution and social equality also remains in party systemsthat have weathered post-materialist transformations.Kitschelt s (1994) new axis of post-materialist partycompetition in Western Europe, for instance, did not doaway with the older materialist, redistributivist dimension.Left parties surviving and thriving after the transformationhave found niches somewhere on the old left side of histwo-dimensional spectrum, although they have alsoneeded to contend with the new new left dimension.

3.3. Conclusion

While the enlightened natural constituency argument isubiquitous, it has unfortunately not been subjected tomuch systematic analysis. Bartels (1996) did estimate whatAmerican elections might look like with a better informedelectorate and unexpectedly found a shift to the right .While interesting, Bartels s observation does not alonediscon rm the hypot he sis about how voter ignorancedisadvantages the left. 14 It may satisfy Americanists, butcomparativists and democratic theorists require moreevidence before concluding the case is representative of other (or most) democracies.

4. Data and methods

Three questions remain insuf ciently answered: (1)Would individuals especially those with lower incomes

make different vote choices once armed with more elec-torally relevant political information? (2) Would thoseindividuals disproportionately switch toward left orcenter-left parties? (3) Would electorates make differentcollective choices if voter ignorance was not as widespreada problem? That is, would political history change andchange toward the left if electorates were betterinformed?

To address these questions I used a regression-basedsimulation method to estimate how additional electorallyrelevant political information might have affected voting atthe individual and aggregate levels in twenty-sevendemocracies in Asia, Australasia, Europe (East and West),North America, and South America. The most differentsystems design permitted analysis across a variety of political environments ( Przeworski and Teune, 1970 ). Oneadvantage of the design was that it offered insights aboutwhether information effects changes in voting behaviordue to added electorally relevant political knowledge

were likely to occur everywhere, as the theoretical argu-ments suggest, or whether vote changes were more likelyin certain types of democracies (e.g. more proportional,multiparty systems). Moreover, the design lets us observe

whether signi cant (i.e. historically consequential) vote switching is likely to be a general phenomenon, orwhether it is more likely limited to speci c types of politicalsystems.

The multi-step statistical simulation procedure origi-nally developed by Scott Althaus (1998, 2003) for a study of Americans policy preferences used existing survey datato simulate a fully informed sample for counterfactualanalysis. 15 The rst of three steps in the simulation proce-dure involved running a multinomial logit model,regressing vote choices on demographic traits, a politicalknowledge (PK) index, and interactions betwee n all of these traits and the PK index (described below). 16 Esti-mating those statistical relationships provided coef cientsused to simulate vote preferences for the same respondentsunder better information conditions.

The second step involved estimating each respondent svote choice with higher PK scores. This involved pluggingthe coef cient values obtained from step one into eachrespondent s actual demographic characteristics,substituting only the new values of the altered knowledgevariable and interaction terms (Althaus, 2003 : 103). The altered knowledge variable was the highest PK score of the sample for example, 9.79/10 in Australia or 8.5/10 inBrazil which was assigned to all respondents in thesimulation. The altered . interaction terms refers toa re-calculated set of interaction variables that wereneeded because of the inclusion of the new PK scores forexample, in Australia, 9.79 * gender, 9.79 * education, and9.79 * income (etc.). The new values helped generatea predicted probability of a vote choice for each respon-dent under superior information conditions. That is, allindividual respondents obtained a new, simulated votevariable ( VoteSim ) that was comparable with the original,self-reported vote variable from the CSES surveys ( Vote-Orig ). Comparisons of VoteSim with VoteOrig allowed bothindividual-level and aggregate-level analysis. For example,I was able to determine how many individuals switched

their votes in each case (e.g. 26.9% in Australia), and theextent to which switching was more likely among indi-viduals in lower income groups. 17 The two vote variablesalso permitted estimations of the net, aggregate effect of switching in each case. There might have been lots of switching toward the British Labour Party, for example,

14 There is also the voluminous literature on the rise of radical rightparties in Europe, which has found that many less educated, lowerincome workers traditionally the left s natural constituency havesupported populist right-wing parties espousing anti-immigrant, anti-

globalization messages in the last two decades. See, e.g. Norris (2005);Givens (2005) .

15 Professor Althaus generously shared additional details via email onDecember 4, 2006. Althaus s method of simulating preferences exploitsa quirk in SPSS whereby the program automatically generates predictedprobabilities (e.g. voting preference) for all cases that have valid valuesfor the independent variables (IVs) in a regression model, even if dependent variables for those cases are missing . Thus, data les can bebuilt using the original set of cases as well as a manipulated set. Thelatter contains cases with the same values on the independent variablesexcept for: (1) political knowledge and (2) interactions between politicalknowledge and the IVs.

16 One advantage of using logit models in this context is that we canavoid assuming a linear relationship between political knowledge andvote choice ( Althaus, 2003 : 323).

17 By switching or switchers , I am referring to my comparisons of those individuals whose votes in the simulations were different than

their reported votes in the CSES surveys (i.e. their self-reported actualvotes).

J.R. Arnold / Electoral Studies 31 (2012) 796 815800

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

6/20

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

7/20

othercharacteristics. Although Zaller (1985 , cited in Bartels,1996 ) demonstrated this was not a factor in the U.S. in the1980 s, we cannot rule out the possibility of bias in othertimes and places.

The CSES did offer commonly used proxy measures of political knowledge, such as education level and self-reported political interest. While education is indeed animportant determinant of citizen political awareness, it isnot a failsafe proxy. Systematic research (and perhaps ourpersonal experiences) tells us educated people are notnecessarily politically aware. That is one reason why somuch effort has been put into research over many decadeson the determinants of political awareness if our intui-tions that education or political interest equals awarenesswere true, survey researchers would have completed the job long ago. Indeed, scholars have found many otherfactors to be just as or more important. In the absence of better options, proxies like education are useful approxi-mations (e.g. Olken, 2009 ). However, the proxy option wasrejected in favor of the more direct measure describedabove. 24

Another commonly used, and available, possibilitywas an index tapping respondents knowledge of politicalfacts. Among other advantages, factual knowledge indicesavoid potential response biases (e.g. pleasing the inter-viewer), because respondents either know or do notknow the answers to unambiguous questions like Whatis the name of the Vice President? Knowing the extent towhich people know the answers to factual questionsprovides useful information about an individual s polit-ical awareness, especially given the huge variance inlevels of political knowledge across populations docu-mented by scores of studies. As Converse (2006 : 304)pointed out, with even a handful of good questions, wecan conclude:

Persons who get a perfect score will be very differentpolitical animals from those who score at the bottom .The reason that even a few stray information items canbe a very usefully diagnostic is exactly because of a property of political apperception masses . the factthat the variance in the volume of these workingpolitical apperceptions across persons in a modernelectorate is simply huge. And it is elementary quanti-tative inference that you can measure to a given level of reliability with many fewer assays when the naturalvariance of a quantity is high than when it is small. Even

a few pokes at information levels, and the observer is

becoming quite well oriented as to expectations forother probes.

Despite their usefulness, factual knowledge indices dohave their problems. They can be criticized for reifyinga shallow construct of political awareness (e.g. questionslike the one about the Vice President s name), or forignoring gender biases in the selection of questions or the

propensity to guess ( Mondak and Anderson, 2004; Stolleand Gidengil, 2010 ). They also introduce potential reli-ability problems for cross-national analysis. For instance,Germans were asked in their CSES survey to identify theforeign minister, the number of Lnder , and the numberof EU members. New Zealanders, on the other hand, wereasked whether Cabinet Ministers must be MPs ,whether there are 99 members of Parliament , andwhether New Zealand has ever had an upper house in itsparliament. Although, as Converse noted, even the seriesof three questions in each survey can provide usefulinformation about a country s distribution of politicalknowledge, the questions in Germany and New Zealand

(and elsewhere) come from separate domains and are of incomparable dif culty. Getting a 70% score in Germanymight be quite different from a 70% in New Zealand. Thepotential reliability problems become even more seriousonce we add dozens of other cases (twenty-seven in thisstudy). 25

The party knowledge index, compared with the alter-natives, was the most direct and reliable measure of political knowledge about voters available electoralchoices. It is also a generally intuitive measure. It assumes,for example, a voter in the U.S. in 2004 who thought GeorgeW. Bush s Republicans were a liberal/left-wing party and John Kerry s Democrats were a conservative/right-wing

party was less politically aware than her neighbors whoknew the parties absolute and/or relative locations. Inaddition to having more (or better) electorally relevantpolitical knowledge, the better informed neighbor was alsosomeone who could connect abstract concepts like the left-right spectrum with real-world politics ( Gordon andSegura, 1997 ). Overall, the party knowledge index seemedthe best option, given the nature of the data, as well as thepractical and conceptual advantages and disadvantages of the available alternatives.

4.2. Income and other measures

Because of income s centrality to the analysis (i.e. itdrives the enlightened natural constituency argument), Iused multiple imputation to resolve the problem of largenumbers of missing income values. The multiple imputa-tion model for all country surveys, except Sweden and theUK, which contained no missing income values, includededucation, age, gender, marital status, urban/rural location,and occupation. The multiple imputation proceduregenerated ve values for income for each respondent. Icalculated the mean of the ve values to create a single

24 The other common proxy mentioned above uses respondents self-assessments of their own political awareness (or sometimes politicalinterest ). Again, in the absence of better data, respondents self-assessments are probably useful, especially in studies examining citizenapathy and system support. However, this kind of measure probablycomes with hard to control biases, including response bias (i.e. pleasingthe interviewer) or other manifestations of respondents painting them-selves in a more positive light. The positive bias might be universal, butsome populations might be more inaccurate in their self-assessmentsthan others. Americans and Canadians for example, might both in atetheir levels of awareness, but Americans might be even worse. Knowing

how much each sample in ated their self-assessments would be inter-esting, but requires information not available in the CSES.

25

Elff (2009) found serious

equivalence

problems with the CSES

sfactual knowledge questions.

J.R. Arnold / Electoral Studies 31 (2012) 796 815802

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

8/20

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

9/20

conclusions from these numbers. Still, knowing that (e.g.)about 32% of French citizens would likely have switched toleft parties (from the right, center, or abstention) with moreelectorally relevant political information does suggesta pretty severe selection problem in the 2002 Frenchinformational status quo.

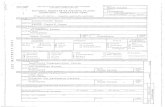

Table 2 aggregates the individual-level results. Inparticular, it shows the magnitude of estimated left andright party gains or losses in the better informed elector-ates. The columns show summations of the changes inparty fates for each ideological party group. 29 For example,in the simulation for France, the Socialist Party gained 1.1%more voters, while the Workers Struggle ( 1.9%), Repub-lican and Civic Movement ( 1.3%), Greens ( 10.6%),Revolutionary Communist League ( 4.9%), FrenchCommunist Party ( 1.9%), and three other small left parties( 0.7) experienced different gains and losses. 30 Altogether,left parties added 10.8% to their vote total in the 2002election. The (virtual) French experience was not unique. In13 of 27 (48%) of the simulated elections, left parties gainedanywhere from 0.6 to 11.5 percentage points, while themean and standard deviation across all 27 cases was 0.25and 8.4, respectively. However, left parties lost out in thesame number of cases, while Japan was the only case wherethe electoral left would have seen no change in vote totals(i.e. the Japanese Communist Party gained 1.4%, while theSocial Democratic Party lost 1.4% in the simulation). All of the estimated changes to party fortunes, as well as parties real ideological locations, as estimated by CSES experts,can be seen in Appendix A .

At this point, the results do not look too favorably upona universally applicable enlightened natural constituencyhypothesis, since left parties as a group lost support in asmany cases as they gained. However, the results areinconclusive for two reasons. First, a more completeunderstanding of the political consequences of these infu-sions of political knowledge would require an equationcombining left and right aggregate changes with changes tocentrist parties, as well as those grouped in the small, non-ideological others category. This is why the values in the

rst two columns of Table 1 are rarely mirror images ( D Leftand D Right). Second, we need to engage in some informedspeculation about government formation after elections.Except for the few places where vote totals translatedirectly into the composition of governments (e.g. clearmajority seat winners in parliamentary systems), knowingthe distribution of votes only gets us halfway to under-standing whether better informed electorates wouldproduce different leaders. The next section uses the simu-lation results to piece together counterfactual electoralhistories in several of the twenty-seven cases to furtherillustrate the political consequences of voter ignorance(space limitations prevented analysis of all).

5.1. Counterfactual electoral histories

Fig. 1 shows the net change in left parties vote totals

that is, left party gains and losses after incorporatingchanges to right, center, and other parties. The estimatedchanges were clearly mixed, with about equal net gains and

Table 2Aggregate changes in voting (left, right, center, other ).

D Left D Right DCenter D Other Net left change

Australia 2.9 7.2 4.4 5.7Brazil 7.9 7.4 15.3Bulgaria 8.2 3.8 13.9 1.9 16.4Canada 10.3 14.5 2.9 1.3 20.6Czech Rep. 23.2 25.4 2.1 46.5

Denmark 5.5 7.8 0.4 12.8 10.9Finland 10.0 6.7 3.5 20.2France 10.8 10.9 21.7Germany 0.2 2.7 3 0.5Hungary 11.6 2.3 11.4 2.5 23.2Iceland 2.5 5.3 7.7 4.9Ireland 0.6 5.2 4.4 1.4Israel 6.1 12.9 8.4 1.6 12.3 Japan 0 2.2 0.7 1.5 0.0Korea 3.8 7.1 3.2 7.7Mexico 7.2 4.1 6.6 3.5 14.3Netherlands 7.3 18.3 3 8.1 14.5New Zealand 11.7 17.9 6.2 23.4Norway 4.7 6.1 0.8 0.6 9.4Poland 6.5 6.9 3.2 2.9 13.1Portugal 0.5 6.5 6.9 13.8 0.9

Spain 3.4 0.2

3.6 6.8Sweden 5.5 1 4.5 11.0Switzerland 11.7 9.4 2.1 23.2Taiwan 9.3 16.8 3.3 4.1 18.7UK 7 7 0.1 13.9USA 3.9 7.6 11.5 7.7

Note: Sometimes totals don t add up to 100 because of rounding.

Fig. 1. Net left change.

29 Chi-square tests con rmed that the differences between actual andsimulated vote totals were statistically signi cant. The Wilcoxon sign testsimilarly con rmed statistically signi cant differences when comparingVoteOrig and VoteSim .

30

The smaller left parties include the Left Radical Party; Citizenship,Action, Participation for the 21st Century; and the Party of the Workers.

J.R. Arnold / Electoral Studies 31 (2012) 796 815804

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

10/20

losses across cases (mean 1.0, standarddeviation 16.9). In some places net gains for left partieswith better informed electorates were quite large, withgains above 10% in Switzerland, France, Finland, Taiwan,Brazil, the Netherlands, Mexico, the U.K., and Israel (the

rst three had gains of about 20% or more). However, netleft losses in several other places were just as substantial,especially in the Czech Republic ( 46.5%!), New Zealand,Hungary, Canada, Bulgaria, Poland, Sweden, and Denmark(all of these cases had net left losses of over 10%). Noticehow hard hit the left would have been in the formerEastern Bloc countries that were once ruled by variousCommunist parties who, deservedly or not, were associatedwith the political left in the region (i.e. instead of mereauthoritarianism masquerading as Communism ).

The likely political consequences (i.e. governmentformation and its aftermath) are probably easier to predictin places with large net left changes than in countries withsmaller net changes (see Appendix A ). Still, some of theformer are worth highlighting, because of the potentially 31

enormous historical consequences that would have fol-lowed. Take, for example, the 2003 Israeli Knesset election.If Israeli voters had been better informed, Ariel Sharon sLikud Party would likely have suffered about a nine pointloss, just enough to put the centrist liberal-secular partyShinui (with 20.7% in the simulation, as opposed to 12.3% inreality), instead of Likud, in the driver s seat (as formateur )for coalition formation. While Shinui might still haveformed a right-leaning cabinet, including Likud, whoformed the government in reality, the process could haveplausibly gone in the other direction, with Shinui puttingtogether a coalition with Labour (15.4%), Meretz (10.5%),and other smaller, secular parties. In any case, Shinui scontrol of the cabinet would have broken open the long-running Likud/Labour alternation of control of thegovernment. 32 It would also have prevented Sharon frombecoming Prime Minister who, among other actions, chosein 2004 to unilaterally disengage from Gaza, whichcreated the political space for Hamas to take control thereafter the 2006 Palestinian election. Sharon also shookthings up by defecting with many supporters from Likud toform the Kadima Party, which, after a later electoral victoryleaving the incumbent Sharon as Prime Minister, led theinvasions of Lebanon and Gaza. Without Sharon s leader-ship, Kadima might never have been formed, and the warsLikud-Kadima initiated might have been avoided, which,among other things, could have perhaps created opportu-nities for post-Oslo Accord peace negotiations.

In the French presidential contest in 2002, better informedvoterswould likelyhave sentLionelJospin (Socialist Party) andNol Mamre (Greens), both left-leaning candidates, into thesecond round, rather than the radical right Jean-Marie Le Pen(National Front) and the incumbent Jacques Chirac (Rally forthe Republic). Chirac s overwhelming second round landslidein the actual election was due to widespread rejection of LePen s extremism. Even left-wing voters who generally

despisedChirac voted forhim.Overall, competitive right-wingpopulist parties in Western Europe and beyond generallysuffered in the counterfactual analyses with better informedelectorates from LePen s NationalFront ( 13%)to theDanishPeople s Party ( 4.5%), List Pim Fortuyn in the Netherlands( 8.4%), the Progress Party in Norway ( 4.1%), and the NewZealand First Party ( 4.4%).

In addition to illustrating just how different politics andpolicy might have been in these counterfactual realities, theIsraeli case from above shows some of the dif culties of interpreting how the new (simulated) results would haveaffected the compositionof governments. Germany providesanother example. In the counterfactual election, the SocialDemocrats (SPD)stillwould have won the most votes, whichwould likely have given them the rst opportunity to forma coalition. However, with a much reduced plurality (31%instead of 38.5%), the SPD would have needed to give theirGreenpartners(Alliance 90/Greens) an even greater stake inthe post-election cabinet, as the Greens improved their(virtual) standing by 4.2%. Joschka Fischer (Greens) probablywould have still taken the Vice Chancellor and ForeignMinistry cabinetseats, butotherGreenswouldhave probablynegotiated for additional key ministries (held by the SPD inreality after 2002). However, Fischer and incumbent Chan-cellor Gerhard Schrder (SPD) would have neededto open upthe cabinet tothe Partyof DemocraticSocialism ( 3.1% in thesimulation) to secure a parliamentary majority. As a result,Schrder s governmentwould likely have hada more distinctleft-wing approach to governance, rather than the ThirdWay approach that garnered him and the SPD so muchcriticism from the German left.

Overall, however, due to the vagaries of coalition bar-gaining after elections in parliamentary systems, we cannotbe certain what might have transpired (i.e. who would haveformed governments) in Germany or other countries,though some parties would surely have improved or wors-ened their bargaining positions. For example, the dramatic2002 election in the Netherlands brought about the end of a long-ruling Labour-led (PvdA) government, which lostpower to an ascendant right-wing coalition led by ChristianDemocratic Appeal (CDA), but propelled to victory by theassassination of the populist right politician Pim Fortuyn,whose death apparently inspired many Dutch voters tosubmit protest votes against the assassin and terrorismmore generally. 33 According to the simulation, however,a well-informed Dutch electorate would have cut theirsupport forFortuyn s party by 8.4%, andcoalition leaderCDAwould have also lost 7%, bringing the coalition s total(including VVD) base of support to 42%, about a third lessthan 2002 s actual total (60.3%). PvdA s incumbent purplecabinet with D 66 and VVD still would not have had theseats to maintain the status quo, but plurality winner PvdA,as the formateur , might have enticed the remaining leftparties, or some smaller parties ( others ), into a new coa-lition. If VVDagreed in this alternatehistory to join a cabinetwith the Green Left and the Socialists both of which faredbetter in the simulation than in reality than the PvdA

31 See below for the reasons why we should treat these results

cautiously.32 Arian (2004 , chapter 5) and Arian and Shamir (2005) .

33

Van Holsteyn and Irwin (2003); Pennings and Keman (2003);Blanger and Aarts (2006) .

J.R. Arnold / Electoral Studies 31 (2012) 796 815 805

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

11/20

would have remained in power, leading an oversized coali-tion with 55.9% of the vote (D 66 s participation actuallywould not have been crucial). Whether or not VVD wouldhave agreed to the deal is impossible to know. However,during that era of Dutch politics, VVD did seem to be moti-vated more by of ce and power considerations than bypolicy concerns, which suggests their participation wouldhave been plausible ( Mller and Strm, 1999 ).

All told, these results present strongly suggestiveevidence that history would likely have unfolded quitedifferently had these electorates been better informedabout the range of political parties from which theyneeded to choose. Of course, the simulations are hypo-thetical re ections of complex reality. Extremely wellinformed populations are unlikely ever to exist, and if they did, electoral politics would already look quitedifferent. Politicians, journalists, and other elite partici-pants in campaigns would likely change their behaviorswhen faced with a well-informed citizenry, and we would

probably observe a very different distribution of politicalparties in each case in the rst place (e.g. some of theparties studied here would not exist, new ones wouldhave emerged). Plus, any counterfactual history arisingfrom the simulations cannot completely grapple with anenormously important factor in government formation:electoral rules that translate votes into seats. We can, forexample, appreciate the insights the simulation providesinto what would have happened in the U.K. with a betterinformed electorate (i.e. Labour and the Liberal Democratswould bene t, and the Conservatives would not).However, given the U.K. s high level of vote/seat dis-proportionality resulting from its single-member districtplurality electoral system, and the Liberal Democrats

geographically concentrated bloc of voting support, thesimulation does not tell us the seat distribution followingthe hypothetical election. A nal caveat comes from thevaried magnitudes of the bootstrapped standard errorsseen in Appendix A (as well as Tables 2 and 3a). The larger

Table 3Vote switching by income quintiles.

Lowest Second Third Fourth Highest Lowest highest Lowest 2 highest 2 a Pattern across income groups

Australia 30.8% 24.4% 26.5% 29.4% 24.7% 6.1% 0.6%

Brazil 67.5% 62.5% 56.3% 60.1% 57.1% 10.4% 6.4%

Bulgaria 51.3% 47.1% 49.3% 55.4% 52.8% 1.5% 4.9%

Canada 57.9% 48.3% 39.0% 49.2% 33.3% 24.6% 11.9%

Czech Rep. 69.0% 73.3% 65.3% 71.9% 61.4% 7.6% 4.5%

Denmark 26.9% 29.4% 27.5% 26.7% 23.4% 3.5% 3.1%

Finland 68.6% 62.5% 56.3% 53.1% 53.5% 15.1% 12.3%

France 71.2% 73.4% 71.4% 67.2% 61.3% 9.9% 8.0%

Germany 47.6% 44.3% 45.8% 44.6% 37.0% 10.6% 5.2%

Hungary 72.1% 59.2% 56.2% 48.8% 39.1% 33.0% 21.7%

Iceland 45.5% 54.8% 45.4% 43.4% 34.9% 10.6% 11.0%

Ireland 48.1% 54.0% 49.4% 47.4% 53.8% 5.7% 0.4%

Israel 50.0% 48.7% 44.8% 53.3% 43.7% 6.3% 0.9%

Japan 54.0% 49.6% 49.0% 47.0% 43.9% 10.1% 6.4%

Korea 68.1% 62.1% 61.9% 53.6% 30.0% 38.1% 23.3%

Mexico 67.9% 68.7% 74.1% 70.8% 66.1% 1.8% 0.1%

Netherlands 50.3% 47.0% 48.7% 41.5% 43.7% 6.6% 6.1%

New Zealand 44.9% 56.1% 54.8% 51.2% 58.1% 13.2% 4.2%

Norway 48.1% 41.3% 36.4% 30.3% 27.3% 20.8% 15.9%

Poland 77.4% 72.8% 75.9% 63.9% 61.7% 15.7% 12.3%

Portugal 59.0% 56.4% 53.8% 50.0% 38.6% 20.4% 13.4%

Spain 42.4% 45.9% 50.4% 34.7% 46.7% 4.3% 3.5%

J.R. Arnold / Electoral Studies 31 (2012) 796 815806

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

12/20

bootstrapped standard errors observed with (e.g.) Aus-tralia s simulation, compared with Brazil s, suggests weshould attach more uncertainty to any conclusionsreached for the former.

Despite these limits, the exercise does begin to addressthe counterfactual questions at the heart of the voterignorance debate: would individuals with more politicalinformation change their votes? Would enough individ-uals switch their votes in ways that would alter politicalhistory? And would critical masses of newly informedvoters disproportionately move towards the left, as theENC argument predicts? While the counterfactual histo-ries show political histories would surely be different inmany of the cases, and the individual-level analysis of thesimulation results show very large number of voterswould switch with more information, we are still left witha mixed body of evidence with which to evaluate the ENCargument. The aggregate results show many cases withlarge net left gains, but at the same time, there are just as

many cases with large net losses. Plus, we cannot explainaway the latter with reference to the disproportionatepresence of post-Communist Eastern European democra-cies all in the early 2000 s still stuck with the legaciesand tarnished reputations (fairly or not) of the left atthe bottom of Fig. 1. New Zealand, Canada, and Swedenare all in the same ballpark (though not of the CzechRepublic, which is clearly an outlier). Furthermore, wehave yet to investigate whether the estimated voteswitching in the simulations occurred across all incomegroups, or whether, as (a modi ed version of) the ENCsuggests, lower income groups are more likely to switch,and switch left.

5.2. Income level and vote switching

Because the relatively poor are disproportionatelypolitically ignorant, we would expect an infusion of elec-torally relevant political information into a polity to cause

Table 3 (continued )

Lowest Second Third Fourth Highest Lowest highest Lowest 2 highest 2 a Pattern across income groups

Sweden 39.3% 43.4% 38.5% 31.9% 23.1% 16.2% 13.9%

Switzerland 69.1% 67.2% 65.3% 57.3% 58.3% 10.8% 10.4%

Taiwan 81.8% 83.1% 83.4% 83.8% 79.5% 2.3% 0.8%

UK 45.9% 42.1% 40.0% 35.0% 32.5% 13.4% 10.3%

USA 63.6% 46.1% 28.7% 28.9% 18.5% 45.1% 31.2%

MEAN 56.2% 54.2% 51.6% 49.3% 44.6% 11.6% 8.3%

Table 3a. Bootstrapped standard errors (for Table 3 )

Lowest Second Third Fourth Highest

Australia 2.4 2.1 2.4 2.7 2.5Brazil 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1Bulgaria 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1Canada 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1Czech Rep. 3.9 3.3 3.4 3.2 4.6Denmark 2.4 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.2Finland 3.8 2.9 3.2 3.3 4

France 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.2Germany 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1Hungary 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1Iceland 3.3 3 3.1 2.7 3.5Ireland 0 0 0 0 0Israel 3.9 3.3 3 3.3 4.4 Japan 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1Korea 4.4 3.1 2.3 3.9 15.3Mexico 0 0 0 0 0Netherlands 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1New Zealand 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1Norway 2.5 2.4 2.2 2.6 2.3Poland 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1Portugal 4.1 2 1.9 2.9 4.3Spain 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.4Sweden 4 3.9 2.8 3 3.3

Switzerland 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1Taiwan 1.7 1.8 2 2.3 2.5UK 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1USA 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1

Note: Values are the percentage of each income group members who switched.Note: Standard errors were computed with a non-parametric bootstrap, based on 1000 resamplings from the data.

a Averages were used for lowest and highest two groups.

J.R. Arnold / Electoral Studies 31 (2012) 796 815 807

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

13/20

more vote switching in lower compared with higherincomegroups. The simulation results in Table 3 indicate the rela-tively poor are indeed more likely to switch ( Table 3 a pres-ents the bootstrapped standard errors). In 23 of 27 cases(85%), individuals fromthe lower income quintilesswitchedmore frequently than those in the highest income quintiles.In Australia, for example, 30.8% of the poorest votersswitched, compared with 24.7% of the richest. In the U.S., itwas 63.6% versus 18.5% a difference of 45.1%,the largest of the set of cases. Across all of the cases, 56.2% of the poorestswitched on average, compared with 44.6% of the richest.The average difference between the two groups the meanpercent of low income switchers minus high incomeswitchers was 11.6%. Broadening the analysis to compareswitching within the two lowest and two highest incomegroups reveals a similar pattern. In 24 of 27 cases (89%), thepoorer two groups were more likely to switch than theirricher counterparts, with an average difference of 8.3%.

Clearly, differences across groups varied cross-nationally. The magnitude of switching varied, as diddifferences between the lower and higher groups. Somecases Bulgaria, Ireland, New Zealand, and Spain buckedthe general trend. In those simulations, voters from higherincome groups were more likely to switch once politicalknowledge was widespread and equal. In Mexico, themiddle and upper-middle income groups were more likelyto switch than the other groups. Nevertheless, a rough(virtual) downward sloping line from lowest to highestincome groups was evident in most of the cases. Theaverage sloping pattern across all 27 cases clearly showsthe expected pattern, even if near-perfect linearity is

evident only in a smaller number of cases (Finland,Hungary, Japan, Korea, Norway, Portugal, Switzerland, theU.K., and the U.S.).

While lower income voters in the simulations were byand large more likely to switch, the counterfactual analysisdid not show a consistent pattern with regard to switchingto the left , in line with the ENC hypothesis. Table 4 shows,for each case, the percentage of switchers from the twolowest income groups who switched either to left or rightparties (e.g. left switchers divided by total switchers foreach group). In 12 of the 27 cases (44.4%), switchers fromthe lowest income group were more likely to switch leftthan right. 34 Of course, that means the poorest voters weremore likely to switch right than left in most (15, or 55.6%) of the cases analyzed here. Moreover, these results mightoverstate switchers left-leaning tendencies, because (realand simulated) voters in Brazil did not even have anopportunity to vote for or switch to a right-wing party. It ispossible that more of Brazil s poorest switchers in 2002would still have switched left than right, but we have noway of knowing.

Overall, the counterfactual analysis produced mixedevidence on the question of whether the poorest switcherswere more likely to switch left than right. Broadening theanalysis to include the two lowest income groups (i.e. not

Table 4Ideological direction of low income switchers.

Lowest incomegroup to left

Lowestto right

Lowest twoto left

Lowest twoto right

Left right(lowest)

Left right(two lowest)

Australia 17.6% 13.5% 23.2% 13.4% 4.2% 9.8%Brazil a 59.2% 55.9% 59.2% 55.9%Bulgaria 4.9% 67.1% 3.7% 61.0% 62.2% 57.3%Canada 20.1% 49.5% 20.4% 48.6% 29.4% 28.3%

Czech Rep 10.0% 66.0% 12.2% 58.1% 56.0% 45.9%Denmark 13.8% 12.8% 15.5% 11.7% 1.0% 3.9%Finland 53.8% 28.3% 54.0% 30.9% 25.5% 23.0%France 43.2% 33.8% 48.6% 28.3% 9.5% 20.3%Germany 33.1% 22.1% 31.3% 21.7% 11.1% 9.5%Hungary 10.3% 35.2% 11.1% 26.2% 24.8% 15.1%Iceland 28.3% 29.3% 26.5% 30.0% 1.0% 3.5%Ireland 20.4% 29.6% 17.1% 30.4% 9.2% 13.3%Israel 8.3% 21.4% 14.7% 22.2% 13.1% 7.6% Japan 17.8% 38.2% 22.5% 37.9% 20.4% 15.4%Korea 42.9% 6.5% 45.2% 23.7% 36.4% 21.5%Mexico 29.5% 13.3% 32.9% 17.0% 16.2% 15.8%Neth. 22.5% 9.4% 25.9% 11.0% 13.1% 14.9%New Zeal. 21.0% 45.1% 17.7% 40.0% 24.1% 22.3%Norway 29.2% 43.7% 26.3% 41.7% 14.6% 15.3%Poland 26.5% 50.4% 31.3% 43.9% 23.9% 12.6%

Portugal 5.9% 29.4% 7.9% 28.5% 23.5% 20.6%Spain 17.9% 46.4% 19.5% 45.2% 28.6% 25.8%Sweden 22.0% 25.4% 25.2% 20.6% 3.4% 4.6%Switz. 34.6% 33.3% 38.8% 28.6% 1.3% 10.2%Taiwan 35.5% 39.8% 33.2% 38.5% 4.3% 5.3%UK 41.1% 17.9% 45.6% 15.9% 23.2% 29.8%USA 42.5% 11.6% 42.1% 21.6% 30.9% 20.5%MEAN 26.4% 31.5% 27.7% 30.6% 4.0% 1.8%a Brazil s 2002 election had no right parties with at least 3% of the vote.

34 Note that the numbers for all cases do not include switchers whomoved from one left party to another left party, one right party to

another, or those who switched to the center (and, as noted above, thosewho stayed put).

J.R. Arnold / Electoral Studies 31 (2012) 796 815808

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

14/20

just the lowest) yielded similar, mixed results: the rela-tively poor were more likely to switch left versus right inonly 13 out of 27 cases (48%). Table 5 adds more detail,showing the percentage of each income groups switchers

that switched left, as well as a ve-point sloping line acrossgroups. Altogether, we have little here with which tosupport the ENC argument, or at least a version withuniversal scope.

Table 5Percentage of switchers who switched left.

Lowest Second Third Fourth Highest Trend

Australia 17.6% 29.5% 27.2% 40.5% 42.7%

Brazil * 59.2% 52.9% 57.0% 48.1% 32.3%

Bulgaria 4.9% 2.6% 2.6% 0.7% 1.8%

Canada 20.1% 20.7% 18.9% 30.0% 21.7%

Czech Rep. 10.0% 14.0% 14.6% 18.5% 24.3%

Denmark 13.8% 17.0% 6.8% 15.0% 15.3%

Finland 53.8% 54.1% 46.5% 42.9% 27.4%

France 43.2% 54.7% 44.0% 44.3% 39.3%

Germany 33.1% 29.3% 21.9% 18.1% 29.7%

Hungary 10.3% 11.9% 16.9% 16.5% 21.0%

Iceland 28.3% 25.3% 37.0% 33.1% 36.4%

Ireland 20.4% 13.5% 23.5% 26.7% 19.8%

Israel 8.3% 19.3% 22.3% 21.7% 30.9%

Japan 17.8% 27.7% 22.8% 20.5% 5.1%

Korea 42.9% 46.4% 44.4% 47.8% 33.3%

Mexico 29.5% 35.3% 26.1% 27.8% 22.9%

Netherlands 22.5% 29.5% 24.3% 25.7% 26.4%

New Zealand 21.0% 16.4% 18.3% 15.0% 21.6%

Norway 29.1% 23.1% 20.0% 13.3% 20.8%

Poland 26.5% 35.4% 35.6% 34.9% 31.9%

Portugal 5.9% 8.3% 12.2% 16.4% 19.6%

Spain 17.9% 19.7% 16.3% 16.3% 0.0%

Sweden 22.0% 27.8% 28.1% 21.5% 17.9%

Switzerland 34.6% 41.6% 35.2% 36.8% 36.7%

Taiwan 35.5% 30.7% 34.7% 35.8% 30.2%

UK 41.1% 47.8% 45.2% 42.8% 40.7%

USA 42.5% 41.6% 27.8% 35.4% 45.2%

MEAN 26.4% 28.7% 27.0% 27.6% 25.7%

J.R. Arnold / Electoral Studies 31 (2012) 796 815 809

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

15/20

6. Conclusion

The preceding analysis adds several important empir-ical advances to the theoretical debate about the politicalimplications of voter ignorance. First, the analysis gives usreason to be skeptical of theorists optimism in the face of widespread voter ignorance, due to the alleged effective-ness of cues and other information shortcuts. The coun-terfactual analysis showed large numbers of voters intwenty-seven democracies (from about 27% to 82%across cases) would likely have switched their votes if theyhad more electorally relevant political information. Thiswidespread switching does not make much sense from theperspective of cue-taking theories that predict voterswould generally make similar decisions no matter howwell informed they appear in surveys. In other words, if shortcuts worked as advertised, then we would not likelysee as much vote switching under better informationconditions.

Second, the analysis directly and systematically exam-ined the enlightened natural constituency hypothesis forthe rst time, despite the argument s long duration inacademic and popular circles. Without recounting thehypothesis in full here (see above), we can say theempirical expectation was that left parties would enjoygreater levels of support if electorates had greater politicalawareness, and much of this extra support would comefrom the left s so-called natural constituency individ-uals in lower socioeconomic strata. In line with theexpectation, the counterfactual analysis showed that thepoorest voters with more information were more likely toswitch votes on average than individuals from otherincome groups. In 23 of 27 cases (85%), individuals fromthe lower income quintiles switched more frequently thanthose in the highest income quintiles. In 24 of 27 cases(89%), the poorest two groups were more likely to switchthan their richer counterparts. This means lower incomevoters probably made more decision errors when they casttheir ballots in the actual elections, given their prefer-ences. Overall, income proved to be a very strong predictorof switching.

While the results supported the theoretical predictionswith regard to vote switching in general, when we exam-ined the political direction of switching, and especially

lower income switching, what emerged was a murkier setof outcomes. Although there were very large numbers of relatively poor voters who switched left in the simulations,switchers from the lowest income groups were more likelyto switch left only in 12 of 27 cases. Including the twolowest income groups in the analysis only increased thatproportion of cases to 13 of 27.

The aggregate-level analysis also found inconsistentcross-national patterns (see again Table 2 and Fig. 1).After accounting for changes to right, center, and, other

(small) party fortunes, we estimated positive net leftchanges in only 12 of 27 cases. Some of these changeswere quite large ( > 10% in Brazil, France, Finland, Israel,Mexico, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Taiwan, and theU.K.), yet negative net changes were also large in aboutas many cases (Bulgaria, Canada, Czech Republic,Denmark, Hungary, New Zealand, Poland, and Sweden).Overall, we found no signi cant statistical relationshipsbetween these observed net changes from the simula-tions and the aggregate political and economic charac-teristics of the cases, including their political andelectoral institutions, their level of economic develop-ment (GDP per capita), and their years of democraticexperience (years of Polity2 score of six or higher)(Marshall and Jaggers, 2010 ).

Perhaps most important, and most interesting, thestudy demonstrates that the composition of severalgovernments, and the course of political history, probablywould have changed if voter ignorance was not as wide-spread. Previous research estimating the voting behavior of well-informed electorates also found signi cant voteswitching at the individual level, but obtained historicallyinsigni cant results (i.e. nothing would have changed).Theorists who denied the real political consequences of voter ignorance likely found succor in earlier work. Thisstudy changes the debate by illustrating much differentcounterfactual histories under different informationconditions in the highlighted cases (e.g. France, Germany,Israel, and the Netherlands). The party-level results, inAppendix A , allow curious readers to ponder whetherdifferent governments would have been formed in theother twenty-three cases.

Appendix 1. Results by party and country

Actual Vote % Sim. Vote % Change SE (Boots.) Ideology

Australia, 2004Liberal Party of Australia 40.8 38.6 2.2 1.35 RightAustralian Labor Party 37.6 32.1 5.5 1.25 LeftAustralian Greens 7.2 15.6 8.4 0.99 LeftNational Party of Australia 5.9 0.9 5.0 0.25 RightOthers 8.5 12.8 4.3 0.89

Brazil, 2002Worker s Party (PT) 46.4 47.7 1.3 0.03 LeftBrazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB) 23.2 15.8 7.4 0.03 CenterBrazilian Socialist Party (PSB) 17.9 16.5 1.4 0.02 LeftSocialist Popular Party (PPS) 12 20 8 0.03 Center-Left

J.R. Arnold / Electoral Studies 31 (2012) 796 815810

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

16/20

Appendix 1 (continued )

Actual Vote % Sim. Vote % Change SE (Boots.) Ideology

Bulgaria, 2001Socialists/Coalition for Bulgaria 17.1 8.9 8.2 0.023 LeftUDF/ODS 18.2 8.5 9.7 0.024 RightMovement for Rights & Freedoms 7.5 0 7.5 CenterNational Movement

Simeon II Simeon II Coalition46.1 52 5.9 0.04 Center-Right

St George

s Day/InternalMacedonian Revol. Org. (IMRO) 3.6 25 21.4 0.036 Center

Others 7.5 5.6 1.9

Canada, 2004Liberal 36.7 33.8 2.9 0.039 CenterConservative 29.6 44.1 14.5 0.042 RightBloc Qubcois 12.4 9.2 3.2 0.024 LeftNew Democratic 15.7 10.2 5.5 0.025 LeftGreen 4.3 2.7 1.6 0.013 LeftOthers 1.3 0 1.3

Czech Republic, 2002Czech Social Democratic Party 30.2 14 16.2 1.169 LeftODS Civic Democratic Party 24.5 34.1 9.6 1.684 RightCommunists 18.5 11.5 7 1.073 LeftCoalition: US-DEU/KDU-CSL 14.3 30.1 15.8 1.587 RightOthers 12.5 10.4 2.1 1.063

Denmark, 2001Liberal Party 31.2 28.7 2.5 1.05 RightSocial Democrats 29.1 22.7 6.4 0.98 Center-LeftDanish People s Party (DPP) 12 7.5 4.5 0.604 RightConservative People s Party 9.1 8.3 0.8 0.642 Center-RightSocialist People s Party (SPP) 6.4 7.3 0.9 0.593 LeftRadical Left/Social Liberal 5.2 5.6 0.4 0.548 CenterOthers 7.1 19.9 12.8 0.912

Finland, 2003Social Democratic Party 24.5 21 3.5 1.274 Center-LeftCenter Party 24.7 17.2 7.5 1.18 Center-RightNational Coalition Party 18.6 17.7 0.9 1.155 RightLeft Alliance 9.9 15.2 5.3 1.104 LeftGreen League 8.0 16.2 8.2 1.113 Center-LeftChristian Democrats 5.3 11.6 6.3 1.003 Center-RightSwedish People s Party 4.6 0 4.6 Right

Others 4.4 0.9 3.5 0.297 France, 2002RPR 19.9 14 5.9 0.044 RightNational Front 16.9 3.9 13.0 0.025 RightSocialist Party 16.2 17.3 1.1 0.049 Center-LeftUnion for French Dem. 6.8 6.6 0.2 0.033 Center-RightWorkers Struggle 5.7 3.9 1.8 0.025 LeftRepublican and Civic Movement

(Citizens Movement)5.3 4 1.3 0.025 Left

Greens 5.3 15.8 10.6 0.048 LeftRevolutionary Communist League 4.3 9.1 4.9 0.037 LeftLiberal Democracy 3.9 7.4 3.5 0.033 RightCommunist Party 3.4 1.5 1.9 0.016 LeftOther right 7.8 12.5 4.7 0.042 RightOther left 4.7 4 0.7 0.026 LeftGermany, 2002

Social Democratic Party 38.5 31 7.5 0.033 Center-LeftAlliance 90/The Greens 8.6 12.8 4.2 0.024 LeftCDU/CSU 38.5 29.6 8.9 0.034 RightFree Democratic Party 7.4 13.6 6.2 0.025 Center-RightParty of Democratic Socialism 4 7.1 3.1 0.017 LeftOthers 3 6 3 0.017

Hungary, 2002Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) 42.1 30.5 11.6 0.044 LeftFidesz Coalition a 41.1 27.6 13.5 0.042 RightAlliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ) 5.6 7.7 2.1 0.025 CenterHungarian Justice & Life Party 4.37 15.5 11.1 0.035 RightCenter Party 3.9 13.2 9.3 0.032 CenterOther 3 5.5 2.5 0.022

Iceland, 2003Independence Party 36.6 29.4 7.2 1.285 RightSocial Alliance Party 26.8 32.8 6 1.317 Center-Left

(continued on next page )

J.R. Arnold / Electoral Studies 31 (2012) 796 815 811

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

17/20

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

18/20

-

8/12/2019 Arnold VoterIgnorance

19/20

Bennett, S.E., Flickinger, R.S., Baker, J.R., Rhine, S.L., Bennett, L.M., 1996.Citizens knowledge of foreign affairs. The Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 1, 10 29.

Berelson, B.R., Lazarsfeld, P.F., McPhee, W.N., 1954. Voting: a Study of Opinion Formation in a Presidential Campaign. University of ChicagoPress, Chicago.

Bourdieu, P., 1993. Sociology in Question. Sage Publications, ThousandOaks, CA.

Converse, P.E., 1964. The nature of belief systems in mass publics.In: Apter, D.E. (Ed.), Ideology and Discontent. Free Press, New

York.Converse, P., 2006. Democratic theory and electoral reality. Critical

Review 18, 297 329.Cronin, J., Ross, G., Shoch, J., 2011. What s Left of the Left: Democrats and

Social Democrats in Challenging Times. Duke University Press,Durham, NC.

Delli Carpini, M., Keeter, S., 1996. What Americans Know about Politicsand Why It Matters. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Downs, A., 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. Harper and Row,New York.

Duch, R.M., Palmer, H.D., Anderson, C.J., 2000. Heterogeneity in percep-tions of national economic conditions. American Journal of PoliticalScience 44, 635 652.

Duch, R.M., Palmer, H.D., 2002. Heterogeneous perceptions of economicconditions in cross-national perspective. In: Dorussen, H., Taylor, M.(Eds.), Economic Voting. Routledge, London.

Elff, M., 2007. Social structure and electoral behavior in comparative

perspective: the decline of social cleavages in Western Europerevisited. Perspectives on Politics 5, 277 294.

Elff, M., April 2-5, 2009. Political Knowledge in Comparative Perspective:the Problem of Cross-national Equivalence of Measurement. Preparedfor Delivery at the Midwest Political Science Association AnnualConference, Chicago, Illinois.

Evans, G., 2000. The continued signi cance of class voting. Annual Reviewof Political Science 3, 401 417.

Frank, T., 2005. What s the Matter with Kansas? How Conservatives Wonthe Heart of America. Macmillan, New York.

Franklin, M.N., Mackie, T.T., Valen, H. (Eds.), 1992. Electoral Change:Responses to Evolving Social and Attitudinal Structures in WesternCountries. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Geys, B., 2006. Explaining voter turnout: a review of aggregate-levelresearch. Electoral Studies 25, 1 27.

Givens, T.E., 2005. Voting Radical Right in Western Europe. CambridgeUniversity Press, Cambridge.

Gordon, S.B., Segura, G.M., 1997. Cross-national variation in the politicalsophistication of individuals: capability or choice? Journal of Politics59, 126 147.

Grofman, B., Feld, S.L., 1988. Rousseau s general will: a con-dorcetian perspective. American Political Science Review 82,567 576.

Grnlund, K., Milner, H., 2006. The determinants of political knowl-edge in comparative perspective. Scandinavian Political Studies 29,386 406.

Heath, A., Tilley, J.R., 2003. Political Knowledge and Values in Britain,1983 1997. Working Paper Number 102. Centre for Research intoElections and Social Trends, Oxford.

Jusko, K.L., Shively, W.P., 2005. Applying a two-step strategy to theanalysis of cross-national public opinion data. Political Analysis 13,327 344.

Kerbo, H.R., 2007. Social strati cation. In: Bryant, C.D., Peck, D.K. (Eds.),21st Century Sociology: a Reference Handbook. Sage Publications,

Thousand Oaks, CA.Kitschelt, H., 1994. The Transformation of European Social Democracy.Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Krause, G.A., 1997. Voters, information heterogeneity, and the dynamics of aggregate economic expectations. American Journal of PoliticalScience 41, 1170 1200.

Kuklinski, J., Quirk, P., 2000. Reconsidering the rational public: cogni-tion, heuristics, and mass opinion. In: Lupia, A., McCubbins, M.,Popkin, S. (Eds.), Elements of Reason. Cambridge University Press,Cambridge.

Lau, R.R., Redlawsk, D.P., 2001. Advantages and disadvantages of cognitiveheuristics in political decision making. American Journal of PoliticalScience 45, 951 971.

Levitsky, S., Roberts, K., 2011. Introduction: Latin America s left turn :a framework for analysis. In: Levitsky, Roberts (Eds.), The Resur-gence of the Latin American Left. Johns Hopkins University Press,Baltimore.

Lodge, M., McGraw, K.M., Stroh, P., 1989. An impression-driven model of candidate evaluation. American Political Science Review 83, 399 419.

Lupia, A., 1994. Shortcuts versus encyclopedias: information and votingbehavior in California insurance reform elections. American PoliticalScience Review 88, 63 76.

Lupia, A., McCubbins, M.D., 1998. The Democratic Dilemma: Can CitizensLearn What They Need to Know? Cambridge University Press,Cambridge.

Luskin, R.C., 1990. Explaining political sophistication. Political Behavior

12, 331 361.Luskin, R.C., 2002. From denial to extenuation (and nally beyond):

political sophistication and citizen performance. In: Kuklinski, J.H.(Ed.), Thinking about Political Psychology. Cambridge UniversityPress, Cambridge.

Luskin, R.C., Bullock, J.G., 2005. Don t Know Means don t Know .Working paper. Stanford Univ.

Manza, J., Hout, M., Brooks, C., 1995. Class voting in capitalist democraciessince World War II: dealignment, realignment, or trendless uctua-tion? Annual Review of Sociology 21, 137 162.

Marshall, M.G., Jaggers, K., 2010. Polity IV project: Political regime char-acteristics and transitions, 1800 2010. Version p4v2010 [ComputerFile]. College Park, MD: Center for Systemic Peace. URL: http://www.systemicpeace.org/ .

Mondak, J.J., 1999. Reconsidering the measurement of political knowl-edge. Political Analysis, 57 82.

Mondak, J.J., Anderson, M.R., 2004. The knowledge gap: a reexamination

of gender-based differences in political knowledge. Journal of Politics66, 492 512.

Mller, W.C., Strm, K. (Eds.), 1999. Policy, Of ce, or Votes? How PoliticalParties in Western Europe Make Hard Decisions. Cambridge Univer-sity Press, Cambridge.

Niemi, R.G., Weisberg, H.F., 2001. What determines the vote? In: Niemi,Weisberg (Eds.), Controversies in Voting Behavior. CongressionalQuarterly Press, Washington.

Nieuwbeerta, P., de Graaf, N.D., 1999. Traditional class voting in twentypostwar societies. In: Evans, G. (Ed.), The End of Class Politics? ClassVoting in Comparative Context. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Norris, P., 2005. Radical Right: Voters and Parties in the Electoral Market.Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Olken, B.A., 2009. Corruption perceptions vs. corruption reality. Journal of Public Economics 93, 950 964.

Page, B.I., Shapiro, R.Y., 1992. The Rational Public: Fifty Years of Trends inAmericans Policy Preferences. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Pennings, P., Keman, H., 2003. The Dutch parliamentary elections in 2002and 2003: the rise and decline of the Fortuyn movement. Acta Politica38, 51 68.

Piazza, T., Sniderman, P.M., Tetlock, P., 1989. Analysis of the dynamics of political reasoning: a general-purpose computer-assisted method-ology. Political Analysis 1, 99 119.

Popkin, S.L., 1991. The Reasoning Voter: Communication and Persuasionin Presidential Campaigns. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Przeworski, A., Teune, H., 1970. The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry.Wiley, New York.

Rahn, W.M., Krosnick, J.A., Breuning, M., 1994. Rationalization and deri-vation processes in survey studies of political candidate evaluation.American Journal of Political Science 38, 582 600.

Schumpeter, J.A., 1942. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. Harper,New York.

Sekhon, J.S., 2004. Quality meets quantity: case studies, condi-tional probability, and counterfactuals. Perspectives on Politics

2, 281

293.Sniderman, P.M., 2000. Taking sides: a xed choice theory of politicalreasoning. In: Lupia, A., McCubbins, M., Popkin, S. (Eds.), Elements of Reason. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.