Approaches To People Of Colour & Food Bank Use In Toronto, Peel Region & York Region ( A K Tehara ...

-

Upload

colour-of-poverty-colour-of-change -

Category

Education

-

view

25.754 -

download

0

Transcript of Approaches To People Of Colour & Food Bank Use In Toronto, Peel Region & York Region ( A K Tehara ...

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of

Toronto, Peel Region and York Region

Auvniet Kaur Tehara

Masters Program in Planning, University of Toronto

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐1‐

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................... 4

1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 5

2. Racialisation of Poverty in Toronto and Surrounding Areas ................................................ 6

Toronto .......................................................................................................................................... 7

Peel Region .................................................................................................................................. 12

York Region .................................................................................................................................. 14

3. Food Security, Health Inequities and People of Colour ...................................................... 16

4. Racism and the Food System ........................................................................................... 18

White Privilege and the Food System ............................................................................................ 20

The Manifestations of White Privilege in Community Food Organisations ....................................... 22

Food Banks – Human Service Delivery ........................................................................................... 22

5. The Food Bank System..................................................................................................... 24

A Neo‐Liberal History of Food Banks ............................................................................................. 24

How Food Bank Organisations Operate in the Area of Study .......................................................... 26

Analysing the Annual HungerCount Survey – Are People of Colour Important? ............................... 29

6. Research Questions ......................................................................................................... 29

7. Method ............................................................................................................................ 29

Qualitative Research – Interviews and Content Analysis ................................................................ 29

Quantitative Research – Geographic Information Systems ............................................................. 30

8. Limitations ....................................................................................................................... 30

Speaking with Food Bank Users of Colour ...................................................................................... 30

Speaking with Food Bank Agencies ................................................................................................ 31

The Impact on Faith‐Based Organisations Delivering Services ......................................................... 31

9. Key Findings .................................................................................................................... 32

Food Bank Locations .................................................................................................................... 32

People of Colour and Food Bank Use ............................................................................................. 36

Services for People of Colour ......................................................................................................... 36

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐2‐

Culturally Appropriate Food .......................................................................................................... 38

People of Colour Staff and Volunteers ........................................................................................... 39

Anti‐racism Training ..................................................................................................................... 40

Input from Community Organisations of Colour in Strategic Planning and Service Delivery ............. 41

Overall Organisational Assessments ............................................................................................. 41

10. How Food Banks are Complicit in Racist Practices ........................................................ 43

Conflation: Immigrants and People of Colour ................................................................................. 43

Kraft Dinner and Canadian Food ................................................................................................... 44

But We Don’t Look at Colour: The Colour‐blindness Food Bank Staff .............................................. 45

Essentialism: They’re All the Same ................................................................................................ 46

The Discourse of Reverse Racism .................................................................................................. 47

11. Recommendations – Dismantling Structural Racism in Food Bank Organisations ......... 48

Education and Awareness ............................................................................................................. 48

Effective and Meaningful Involvement and Engagement of People of Colour .................................. 49

Building Partnerships to Increase Culturally Appropriate Food ....................................................... 49

Monitoring the Experience of Food Bank Users of Colour ................................................................ 49

Funding Requirements .................................................................................................................. 50

Stakeholder Consultation and Involvement of People of Colour Organisations ............................... 50

12. Conclusion ................................................................................................................... 50

REFERENCES ............................................................................................. 52

APPENDIX A: REGIONAL COMPARISON OF THE PERCENTAGE OF VISIBLE MINORITIES

(2006) AND THE POPULATION BELOW THE LOW INCOME CUT‐OFF (2005) ................ 57

APPENDIX B: FOOD BANK NETWORK ORGANISATIONAL CHART ............................. 59

APPENDIX C: CODE OF ETHICS FOR FOOD BANK COMMUNITY ................................. 60

APPENDIX D: ASSESSING ORGANISATIONAL RACISM ........................................... 61

APPENDIX E: INTERVIEW QUESTIONS .............................................................. 63

APPENDIX F: MEMBER AGENCY FOOD BANKS .................................................... 65

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐3‐

APPENDIX G: FOOD BANKS WALKING DISTANCE FROM TTC SUBWAY STATIONS AND

TORONTO’S PRIORITY NEIGHBOURHOODS ........................................................ 67

LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES

Table 2.1: Income Statistics in Constant (2005) Dollars ........................................................................... 6

Figure 2.2: Percentage of Population Below the Low Income Cut‐Off (2005) ......................................... 9

Figure 2.3: Percentage of Visible Minorities by Census Tract and 13 Priority Neighbourhoods (2006) .. 10

Figure 2.4: Category of Low Income and Percentage of Visible Minorities in Toronto by Census .......... 11

Figure 2.5: Comparison of the Percentage of Visible Minorities (2006) and the Population Below the

Low Income Cut‐Off (2005) in Peel Region............................................................................................ 13

Figure 2.6: Comparison of the Percentage of Visible Minorities (2006) and the Population Below the

Low Income Cut‐Off (2005) in York Region ........................................................................................... 15

Figure 4.1: Racism and the Food Cycle .................................................................................................. 20

Figure 5.1: Food Bank Agency Locations in Toronto, Peel Region and York Region .............................. 28

Figure 9.1: Food Bank Agency Locations and Toronto’s 13 Priority Neighbourhoods (2006) ................ 33

Figure 9.2: Food Bank Agency Locations, Percentage of Population Below the Low Income Cut‐off

(2005), Visible Minority Percentages and Toronto’s 13 Priority Neighbourhoods (2006) ....................... 34

Figure 9.3: Food Bank Agency Locations and Category of Low Income (2005) and Visible Minority

Percentages and Toronto’s 13 Priority Neighbourhoods (2006) ............................................................ 35

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐4‐

Executive Summary

The world does not become raceless or will not become unracialized by assertion. The act of

enforcing racelessness . . . is itself a racial act. (Morrison, 1992)

Food banks have become the primary response to food insecurity in Canada. Little

information is known about the food insecurity issues faced by people of colour. The purpose

of this research paper is to assess how food bank organisations, in the area of study, view

people of colour in their operations. Attention was focused specifically on how the issue of

race and racism are conceptualised at an organisational level.

I conducted nine interviews with executive directors and staff within four food bank

organisations: Daily Bread Food Bank, North York Harvest Food Bank, York Region Food

Network and The Mississauga Food Bank. I conducted an evaluation on the decisions

influencing the location of food bank agencies, the availability of culturally appropriate food,

and special services provided to people of colour within food banks.

I discovered how food banks organisations are complicit in racist practice by not

acknowledging race as a factor in service access and delivery, conflating people of colour and

immigrants thereby linking whiteness to Canadian identity, and through the perceptions of

reverse racism. My findings indicated an array of responses and organisational ideologies

towards race and racism. This included organisations willing to examine race and re‐think

operations along the lines of anti‐racism, to others that do not address or seek to address

linguistic, cultural, and racial barriers within their service delivery.

My recommendations include steps towards organisation change to address

structural racism within food bank organisations. These recommendations include: education

efforts geared at understanding different and unique struggles of people of colour when

accessing food banks; involvement of people of colour in the administration and organisation

of food bank organisations; working with people of colour grocery stores and ethnic media

outlets to change current donation partners, increasing the availability of culturally diverse

food; monitoring of discrimination and racism in food bank organisations’ member agencies

and lastly, making funding contingent to their member agencies upon implementation of anti‐

racist policies and practices for food bank agencies.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐5‐

1. Introduction

Food banks have been the primary response to food insecurity in Canada. As such,

the Ontario Food Bank Network is responsible for delivering large amounts of food across the

province for emergency food relief. Food bank organisations are the collection and distribution

organisations responsible for overseeing numerous food relief programmes including food

bank agencies. The Daily Bread Food Bank, the North York Harvest Food Bank, the

Mississauga Food Bank, and the York Region Food Network are all food bank organisations. A

food bank agency is referred to as the localised individual agencies responsible for delivering

emergency food supplies to food‐insecure households and individuals.

The central research question guiding my work was: how do food bank organisations

contemplate race? People of colour are referred to a group or persons who because of their

physical characteristics are subjected to differential treatment. Their minority status is the

result of a lack of access to power, privilege, and prestige in relation to the majority group

(Henry and Tator, 2005). People of colour can be immigrants however, not all immigrants are

people of colour. The distinction of the two terms is essential within this analysis as often

issues of immigration process and settlement are used to evade the discussion of racism. My

analysis uses critical race theory, including democratic racism and white privilege to explore

how food banks are complicit in racism.

While it is widely acknowledged that food insecurity is strongly linked to low income

households, current data also suggests that a disproportionate number of these households

consist of people of colour. Unfortunately, despite growing evidence of racialised poverty in

Ontario there is currently no comprehensive data on the specific food insecurity problems of

this group and the scant available research has largely focused only on immigrants. For

example, the Daily Bread and North York Harvest affirm that food bank use among immigrants

has increased, but do not measure if this is disproportionately true for people of colour nor

whether it has also increased among people of colour who are not recent immigrants. This is,

in part due to the response to food security in Western developed nations generally being

dominated by white middle‐class individuals who are often unaware of the institutional racism

within their organisations. In response to this gap, my research focuses on examining how

food bank organisations view people of colour within their operations (both staff and users).

My recommendations will offer suggestions on how food bank organisations can address these

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐6‐

issues by incorporating anti‐racist policies and initiatives within their practices in the area of

study1.

2. Racialisation2 of Poverty in Toronto and Surrounding Areas

Poverty rates among people of colour in Canada, particularly recent immigrants of

colour are higher and growing. In 2001 poverty among people of colour was 17% higher than

the rest of the Canadian population (Jackson, 2001). Table 2.1 shows a comparison of median

and average individual income; earnings among people of colour are lower for both categories.

Table 2.1: Income Statistics in Constant (2005) Dollars

Canada Ontario Toronto

Status Visible3

Minority

Not a Visible Minority

Visible Minority

Not a Visible Minority

Visible Minority

Not a Visible Minority

Average Income

2000 27,351 34,226 29,213 38,457 28,946 45,597

2005 27,750 36,847 28,890 40,531 28,640 48,776

Median Income

2000 19,751 25,732 22,048 28,847 22,414 33,489

2005 19,115 26,863 20,052 29,396 20,142 31,985

Data Source: Statistics Canada, 2006 Census of Population, 2006 Census.

Poverty (measured by the low income cut‐off4) increased for all immigrants between 1991 and

1996; this trend was pronounced for immigrants of colour. Immigrants of colour are

significantly more likely than white immigrants to have lower incomes, regardless of their time

in Canada (Palameta, 2004). In Ontario racialised communities are two to four times more

likely than white families to fall below the low‐income cut‐off (Colour of Poverty, 2008).

1 The City of Toronto, York and Peel Region.

2 Racialisation refers to the process by which ethno‐racial groups are categorised, stigmatised, inferiorised, and marginalised as the “others” (Henry and Tator, 2005).

3 Statistics Canada uses the Employment Equity Act that defines visible minorities as 'persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non‐Caucasian in race or non‐white in colour.'

4 Income levels at which families or persons not in economic families spend 20% more than average of their before tax income on food, shelter and clothing.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐7‐

Immigrants of colour experienced the largest increase in poverty levels in the area of study,

from 20.9% in 1991 to 32.5% in 1996; this was higher than both the Ontario and Canadian

averages (Children’s Aid Society, 2008) (Appendix A). These numbers indicate the growing

intersection between class and race. Ornstein (2001) has focused his research on the socio‐

economic polarisation between Toronto’s white and non‐white population.

There has been a great amount of research conducted on the declining socio‐

economic status of people of colour in Canada, Ontario and specifically the Greater Toronto

Area (Ornstein, 2001; Kazemipur, 1997 and United Way, 2004). The research has focused on

the breakdown of the Canadian welfare system, and of immigrant settlement and the

integration process. Issues of structural racism and discrimination are notably absent within

the literature.

Toronto

People of colour account for 47% of Toronto’s population (City of Toronto, 2009).

Scarborough, North York, Etobicoke, York, and East York have all had a combined increase in

higher poverty neighbourhoods, from 15 in 1981 to 92 in 2001 (United Way 2004). Figures 2.1

and 2.2 show areas across Toronto with high concentrations of people of colour and those

living below the low income cut‐off. The maps indicate a similar pattern for both variables.

There is a concentration of people of colour located at the outer edges of the city especially to

the north; the centre of the city has the lowest levels of people of colour. Figure 2.4 shows the

relationship between both variables; with the areas in blue indicating areas with high levels of

the prevalence of low income and concentrations of people of colour. This indicates a

concentration of poverty within the City’s suburban areas, especially in Scarborough. The

majority of Toronto’s 13 Priority Neighbourhoods are comprised of people of colour (Figure

2.3).

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐8‐

0 3 6 9 121.5Kilometers

Figure 2.1: Percentage of Visible Minorities by Census Tracts in Toronto (2006)

Data Source: Statistics Canada, Profile for Census Metropolitan Areas, Tracted Census Agglomerates and Census Tracts, 2006 Census.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐9‐

0 3 6 9 121.5Kilometers

Figure 2.2: Percentage of Population Below the Low Income Cut‐Off (2005)

Data Source: Statistics Canada, Profile for Census Metropolitan Areas, Tracted Census Agglomerates and Census Tracts, 2006 Census.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐10‐

Figure 2.3: Percentage of Visible Minorities by Census Tract and 13 Priority Neighbourhoods (2006)

Data Source: Statistics Canada, Profile for Census Metropolitan Areas, Tracted Census Agglomerates and

Census Tracts, 2006 Census, City of Toronto, Toronto Neighbourhoods (2003), Neighbourhood Services

Department.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐11‐

Figure 2.4: Category of Low Income and Percentage of Visible Minorities in Toronto by Census

Tract5

Data Source: Statistics Canada, Profile for Census Metropolitan Areas, Tracted Census Agglomerates and Census Tracts, 2006 Census.

5 A median value was derived for both the prevalence of low income (low‐income cut‐off) and the percentage of visible minorities for all the census tracts for Toronto. Each individual census tract was compared to the medial value for prevalence of low income and percentage of visible minorities. Each census tract was grouped into the following categories based on if it was above or below the median value for prevalence of low income and the percentage of visible minorities:

Above Low Income Cut‐off Median and Above Percentage of Visible Minorities Median – blue

Above Low Income Cut‐off Median and Below Percentage of Visible Minorities Median – pink

Below Low Income Cut‐off Median and Above Percentage of Visible Minorities Median – orange

Above Low Income Cut‐off Median and Below Percentage of Visible Minorities Median – green

A bivariate correlation reveals that there a statistically significant strong positive relationship between both variables.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐12‐

Peel Region

People of colour account for 50% of Peel Region’s population, with 49.04% in

Mississauga, 7.2% in Caledon and 57.03% in Brampton (Region of Peel, 2009). Peel Region has

one of the highest immigration rates, second to Toronto, in Canada. Individuals living below

the low‐income cut‐off increased from 11.5% in 2001 to 15% in 2006. Immigrants and racialised

communities are among the groups who have experienced an increase in poverty (Peel

Provincial Poverty Reduction Committee, 2009). Figure 2.5 indicates visually the strong

relationship between people of colour and the incidence of low income within the Region; the

pockets of poverty and the concentrations of people of colour are similar in pattern as Toronto

and York Region.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐13‐

0 3 6 9 121.5Kilometers

Figure 2.5: Comparison of the Percentage of Visible Minorities (2006) and the Population Below the Low Income Cut‐Off (2005) in Peel Region

Data Source: Statistics Canada, Profile for Census Metropolitan Areas, Tracted Census Agglomerates and Census Tracts, 2006 Census.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐14‐

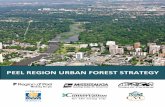

York Region

People of colour account for 30% of York Region’s total population. Municipalities

with the largest concentrations of people of colour include Markham (56%), Richmond Hill

(40%) and Vaughan (19%) (York Region, 2009). There was a 53% increase in the number of

people of colour living within the region between 2001 and 2006; this population is mostly

located in the Southern parts of the Region in Markham and Vaughan. Recent immigrants are

almost three times more likely to fall below the low income cut‐off. Figure 2.6 shows a

comparison of people of colour and incidence of low income revealing a similar pattern of

concentrated poverty among people of colour as in both Toronto and Peel Region.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐15‐

0 3 6 9 121.5Kilometers

Figure 2.6: Comparison of the Percentage of Visible Minorities (2006) and the Population Below the Low Income Cut‐Off (2005) in York Region

Data Source: Statistics Canada, Profile for Census Metropolitan Areas, Tracted Census Agglomerates and Census Tracts, 2006 Census.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐16‐

3. Food Security, Health Inequities and People of Colour

In order to understand the emergence and existence of food banks in the area of

study the issue of food security must be examined. Food insecurity is defined as:

Limited, inadequate, or insecure access of individuals and households to sufficient, safe,

nutritious, and personally acceptable food to meet their dietary requirements for a

productive and healthy life. (Tarasuk, 2005)

There are four main parts of food security described in the literature:

Availability: sufficient supplies of food for all people at all times.

Accessibility: access to food for all at all times.

Acceptability: culturally acceptable and appropriate food and distribution systems.

Adequacy: nutritional quality, safety, and sustainability of available sources and methods

of food supply. (Brink, 2002)

Food‐insecure individuals face problems in their physical and emotional health as well

as social consequences. Potential public health concerns of food insecurity include hunger,

malnutrition, reduced health and quality of life. Risks include low levels of vitamin A, folate,

iron and magnesium intake and numerous other nutrient deficiencies. Children living in food‐

insecure homes have greater levels of absenteeism from school, young children and

adolescents experience more emotional problems and adults face higher rates of depression

and anxiety (Harrison et al., 2007). Individuals in food‐insecure households are more likely to

delay or omit filling prescriptions for needed medicine and follow up on essential medical care

(Harrison et al., 2007).

Harrison et al. (2007) indicate 64% of adults in food‐insecure households were

overweight compared to only 58% of adults in food secure homes. The lack of access to

nutritious food has been linked with poor health including the overeating of available foods

resulting in obesity (Rush et al., 2007). The local food environment has substantial impacts on

racial and socio‐economic disparities in obesity‐related health outcomes including diabetes,

cardiovascular and mental health (Galvez et al., 2007). The American College of Physicians has

indicated that targeted marketing of unhealthy fatty foods, tobacco and alcohol has been a

contributor to the poor health of people of colour (Shavers and Shavers, 2006). These

inequities are the same for different communities; a U.S. study indicates predominantly black

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐17‐

neighbourhoods are less likely to have food stores available compared to the Latin community

(Galvez et al., 2007).

Studies have indicated poorer areas and non‐white areas also have fewer fruit and

vegetable markets, bakeries, specialty stores, and natural food stores (Galvez et al., 2007;

Short et al., 2007). Areas such as these are known as food deserts, “places where the

transportation constraints of carless residents combine with a dearth of supermarkets to force

residents to pay inflated prices for inferior and unhealthy foods at small markets and

convenience stores” (Short et al., 2007). Poppendieck (1998) writes how many of these small

markets end up with damaged and inferior items. A recent report released by the Canadian

Heart and Stroke Foundation reveals Jane and Finch residents pay the highest prices to buy

basic groceries required for a healthy diet in Toronto (Godfrey, 2009). The presence of these

differences along racial lines introduces questions on the existence of structural and

institutional barriers that produce these results. Inequality, discrimination and poor health are

all the symptoms of the manifestation of racism present within all layers of the food system

(See Figure 7.1) (Slocum, 2006).

An examination of the food insecurity issues faced by people of colour was not

conducted in this research. As increasing numbers of people of colour face declining socio‐

economic conditions, studying their food security concerns should be a priority for researchers

and policymakers. Of the studies conducted within this area most have been focused on new

immigrants (Rush et al, 2007). Che and Chen (2001) indicated the level of immigrants reporting

at least one episode of food insecurity in 2000 was not significantly higher than the Canadian‐

born but the patterns of food bank use among immigrants as reported by the Daily Bread and

North York Harvest challenge these findings in Toronto.

There is little data available measuring or studying food insecurity, specifically among

people of colour. The Daily Bread’s (2008) agencies indicate 46% of food bank users in the area

of study are immigrants. North York Harvest has indicated that of its five largest agencies, 72%

of its users were immigrants in 2008. These numbers are a likely an underestimation of users

due to linguistic difficulties, knowledge of food banks and cultural barriers to access. Both

organisations anecdotally and through immigrant‐user rates as a proxy, have affirmed an

increase in people of colour accessing food banks. Considering recent immigration patterns

people of colour comprise a large segment of food bank users.

The most accurate and direct method of measuring household food insecurity is by

examining household income levels (Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk, 2008). Low income is the

greatest predictor of household food insecurity; there is an inextricable link between food

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐18‐

insecurity and income adequacy (Rush et al., 2007). The descriptive variables used to measure

household food security include: household socio‐demographic characteristics: household

type, household income, education and home ownership (Health Canada, 2007).

Largely, the response to food security issues have been focused on food provisioning

and food related behaviour, instead of addressing the income adequacy issues. The Daily

Bread has focused on creating awareness of the latter, stressing “no one is food‐insecure, they

are income insecure”. Within low income households food insecurity is strongly linked with the

flow of household resources and the financial pressures on these resources (Brink, 2002;

Rideout et al., 2006; Tarasuk, 2005). Close to 35% of people in low income households reported

some form of food insecurity in 1998 and 1999, this number had increased to 48.3% in 2004

(Health Canada, 2007). Those who are on social assistance are also at a high risk of food

insecurity (Che and Chen, 2001). In 2004, more than 1.1 million (9.2% households) were food‐

insecure at some point in the year. Overall, 2.7 million Canadians, or 8.8%, lived in food‐

insecure households (Canadian Community Health Survey Cycle 2.2, 2007). As more people of

colour are finding themselves with declining incomes and socio‐economic status, food

insecurity is an issue many will be facing.

4. Racism and the Food System

Race is a social construction, without biological, genetic or fixed characteristics. Race

is a subjective construction that society “invents, manipulates or retires when convenient”

(Delgado, 2001). Race intersects with other characteristics including sex, class, national origin

and sexual orientation. The examination of these variables in relations to each other is referred

to as “intersectionality” (Delgado, 2001).

Racism is manifested in many different ways and can be viewed in the following two

categories:

Individual Racism: A form of racial discrimination that stems from conscious, personal prejudice.

Systemic Racism: Racism that consists of policies and, practices, and procedures of various institutions that result in the exclusion or advancement of specific groups of people. There are two manners in which systemic racism works: 1) institutional racism: racial discrimination that derives from individuals carrying out the dictates of others who are prejudiced or of a prejudiced society; and 2) structural racism: inequalities rooted in the

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐19‐

system‐wide operation of a society that exclude substantial numbers of particular groups from significant participation in major social institutions (Henry and Tator, 2005).

In the context of this research, racism is discussed in an institutional context focusing

on the organisation. Delgado (2001) describes two forms of racism as a “two‐headed hydra”.

The first is outright bigotry – the “oppression on the grounds of who they are.” The second is

subtle and the less easily identifiable, systemic racism. This second form of racism present in

most Western democratic nations is described by Henry and Tator (2005) as democratic racism

but is not completely unconnected from individual racism.

Essed (1991) examines a new approach to the study of racism which connects

structural forces with routine situations that occur through daily practices; this is referred to

“everyday racism”. Everyday racism helps to integrate the macro (structural) racism and micro

(individual) racism as many times they are seen to be completely unconnected, but structural

racism is perpetuated by the everyday actions of individuals. Structural racism often places the

individual outside of the institution but the role of the individual in the replication of racism

cannot be ignored:

Structures of racism do not exist external to their agents – they are made by agents – but

specific practises are by definition racist only when they activate existing structural racial

inequality in the system. (Essed, 1991)

Everyday racism is replicated through daily activities of individuals such as joke telling and

essentialism. “When these racist notions and actions infiltrate everyday life and become part

of the reproduction of the system, the system reproduces racism” (Essed, 1991).

Organisational racism is performed through individual actions; systemic and individual racism

are intertwined. I was interested in examining the individual actions and beliefs of my

interviewees and how this perpetuated systemic racism.

Democratic racism is an ideology that argues, “two conflicting sets of values are

made congruent” (Henry and Tator, 2005). It can be described as the conflict between liberal,

egalitarian values of social justice fairness, with the existence of racist attitudes, perceptions

and assumptions. Democratic racism examines how white privilege materialises through

seemingly benevolent organisations such as food banks.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐20‐

White Privilege and the Food System

Racism exists within the food system in different ways and has historically been

responsible for shaping the entire food system. Slocum (2006) describes how the food system

in North America is built on the foundations of genocide, slavery and layers of racist

institutions and practises, this is demonstrated in the chart below.

Figure 4.1: Racism and the Food Cycle

Native American land theft.

60% of black farms lost since 1910.

75% of farm workers in US born in Mexico.

Half the wages of mining, construction. Highest work-related injuries.

Food processing plants, particularly in rural areas largely employ non-White immigrant labour and Blacks (meat processing and poultry processing in particular).

Average grocery store is two and a half times smaller in poor neighbourhood; study found 67% of products more expensive in smaller stores.

Food insecurity is more prevalent and highly correlated with obesity in communities of colour.

Hog farming, landfills filled with food burden disproportionately communities of colour.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐21‐

Data Source: Centre for Social Inclusion, Structural Racism and Our Food, Understanding the Problems Identifying the Solutions, Centre for Social Inclusion.

White privilege is based on the idea the privileges that whites enjoy are given because

of their whiteness regardless of income and nationality. Many whites do not often perceive this

as a privilege and do not recognise the benefits they enjoy because of their whiteness. The

disadvantages of people of colour are not seen as a direct consequence of their privilege

(Delgado, 2001; Pulido, 2002; Pulido, 2006). This is often a difficult subject and concept for

many whites, as they do not feel that they are part of racist institutions unless they are

personally malicious towards people of colour, but white privilege is not based on individual

bigotry. Delgado (2001) describes how the semantics surrounding whiteness is related to

“good and goodness” whereas blackness is described as “darkness and evil”. Whiteness is the

point of reference, it is the “normal” to which all other groups are compared. This binary

establishes a commonness among non‐whites which is problematic because different groups

are racialised in different ways and face oppression differently.

Economic positions are informed by the racial meanings attached to various groups, as

well as by the needs of capital, the nature of resistance, and the presence of other racially‐

subordinated populations. (Pulido, 2006)

For example, poverty among Torontonians of Vietnamese origin is much greater than it

is among Torontonians of Japanese origin. Kazemipur (1997) indicated in his study that Indians

have one of the highest rates of immigration to Canada but comparatively low levels of

poverty. The most disadvantaged include the Afro‐Caribbean ethno‐racial groups: Ethiopians,

Ghanaians and Somalis.The connection between racism and economic oppression is an

important area of examination within the context of food security. This disparity is evident in

the American literature; households headed by blacks have a 73% higher risk of food insecurity

than do economically similar white households (Bartfeld, 2003).

The link between food insecurity and the white privilege discourse is an important area

of examination. “Effective community change cannot happen unless those who would make

change understand how race and racism function as a barrier to community, self‐

determination and self sufficiency” (Shapiro, 2002). Community food organisations work to

promote fair prices and sustainable practices in farming as well as accessible, affordable, and

culturally appropriate nutritious food for all (Slocum, 2006).“Community food is a white effort”

which in many organisations is servicing mainly non‐white users (Slocum, 2005).

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐22‐

Whiteness is apparent in the idea of and approach to justice promoted by community

food, in its appeal to whites who are able and willing to buy organic or support local farmers

and in the white spaces of farmers markets, coops and Whole Foods. (Slocum, 2006). Slocum

(2006) and Guthman (2008) examine the impact of the white dominated food security

movement on people of colour.

The Manifestations of White Privilege in Community Food Organisations

Two of the manifestations of whiteness in community food initiatives is colour‐

blindness and universalism (Guthman, 2008). Colour‐blindness, or evasiveness contends that

whites insist they do not notice the skin colour of a racial (Frankenburg, 1993; Henry and Tator,

2005; McKinney, 2005). This stems from the fear that the recognition of one’s race will be

deemed racist. Morrison (1992) provides a counterpoint on the impact of colour‐blindness,

“the world does not become raceless or will not become unracialized by assertion. The act of

enforcing racelessness . . . is itself a racial act” (Morrison, 1992). Guthman (2008) indicates that

colour‐blindness erases the privilege that whiteness produces. This refusal to recognise colour

is a way of organisations and individuals to side‐step the racism and obstacles people of colour

face. It allows them to continue to privilege whiteness and ignore issues of systemic racism by

focusing on individual bigotry as isolated, unconnected acts, committed by ignorant

individuals. Universalism is the assumptions held by whites, and are widely accepted by all,

including people of colour. Food banks and the community food response (community

gardens, community kitchens, food banks) to food insecurity are rooted in the structures of

white privilege.

Food Banks – Human Service Delivery

Food banks are a particularly important “human service” to examine, because of the

emotional impacts in accessing emergency food what can be a dehumanising and

depersonalised experience (Poppendieck, 1998). The charitable undertones of the “giver” and

“receiver” binary can be exacerbated by racial undertones of inferiority of the food bank users

of colour (Poppendieck, 1998). Since they were established food banks have been highly

criticised for their rigid requirements, including proof of identity, address, household

composition and the use of means‐testing for eligibility (Poppendieck, 1998). Means‐testing in

social services (public or non‐profit) is one of the ways the individual model functions in the

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐23‐

neo‐liberal economy; that is one’s situation, in this case food insecurity, is a cause of their

personal failings (Walks, 2006).

The greatest barriers that affect human‐service delivery include the

underrepresentation of people of colour in mainstream human‐service organisations (Henry

and Tator, 2005). The differential treatment and marginalisation of people of colour working in

the human service‐delivery is also a challenge. People of colour and those who belong to other

marginalised groups including women, immigrants and seniors, are particularity vulnerable

within these organisations. Although there is a lack of formal statistical information on food

bank use among people, all anecdotal evidence and immigration data suggests that people of

colour comprise a significant portion of all food bank users. Racist ideologies have a profound

effect on the administration and operation of human‐service delivery:

Racial bias may be reflected in the modes of treatment and approaches to problem

resolution, which may ignore the effects of systemic racism on the client, failing to

recognise cultural values and community norms. (Henry and Tator, 2005)

The manifestation of racism within human‐service delivery includes:

The existence of racial and cultural barriers to services.

The reluctance of partners and funders to support additional funding despite the dramatic rise in immigrants and refugees.

The existence of racist assumptions in hiring practices and recognition of foreign credentials.

Barriers to services offered to people of colour in terms of transportation, linguistic services and cultural understanding.

The lack of people of colour in positions of power; people of colour are recruited to serve members of their community as front line staff but have little power or influence over the organisational operations (Henry and Tator, 2005).

Although through my research I was not able to provide empirical data on the

demographics of my interviewees, almost all the executive directors and staff I spoke with

were white, this trend was also observable for most of the board of directors. In her study

investigating community food organisations in the North Eastern United States Slocum (2006)

examined 66 organisations, focusing on 13 organisations with staff between 10 and 35 people.

In her findings she discovered there were no people of colour in the executive director position.

Within the composition of authority positions, only 16% of employees were people of colour.

Her interviews with community food organisations (executive directors and staff) revealed a

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐24‐

willingness to examine and talk about race, but a general lack of previous thought on race

within their organisations and the role of structural racism within their operations (Slocum,

2005).

5. The Food Bank System

A Neo‐Liberal History of Food Banks

Food insecurity became a recognised problem in Canada in the late 1980s. The shift

of the Canadian welfare state away from adequate welfare benefits combined with the

joblessness, low wages and the recession of the 1980s had an adverse impact on the economic

well‐being of many Canadians. Communities began to mobilise to provide temporary food

relief programmes for individuals and families in (Banks, 2002; Poppendieck, 1998; Tarasuk,

2005; Tarasuk & Eakin, 2003). Riches (1986) defines food banks as:

...centralized warehouses or clearing houses registered as non‐profit organizations for

the purposes of collecting, storing and distributing surplus food (donated/shared), free of

charge either directly to hungry people or to front‐line social agencies which provide

supplementary food and meals. (Riches, 1986)

Food bank organisations collect and distribute food to smaller food bank agencies who deliver

emergency food supplies to users.

The institutionalisation of food banks, charitable non‐profit and faith‐based

organisations as a response to food security can be linked to the fundamental shift in social and

economic policies in Canada. In Canada, both the awareness of food insecurity as a domestic

problem and the development of responses to this problem have originated at the community

level as opposed to government action (Tarasuk, 2001).

The response to this reduction in publicly funded programmes for the poor and

underemployed food banks have moved to tend to food insecurity with the donation and

redistribution of surplus food that cannot be sold because of various reasons. Federal and

provincial governments have downloaded their responsibilities in responding to food insecurity

to faith‐based and volunteer organisations. These surplus food redistribution schemes have

also been used in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, France,

Germany, Spain, Italy, Belgium, Poland, Portugal, Greece, Ireland, Czechoslovakia, and

Romania. (Tarasuk and Eakin 2003). Some social policy question arising from the emergence of

food banks include: who is benefitting from food banks? Are food banks a viable solution to

food insecurity?

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐25‐

The first food bank in Canada was set up in Edmonton, Alberta, by Gerard Kennedy in

1981. Food banks were started as a temporary solution 1980s recession. Today, food banks

have become the primary response to food insecurity in Canada (Riches, 2002; Tarasuk, 2005).

This institutionalisation is supported by three key factors. First, the emergence of the Canadian

Association of Food Banks (now Food Banks Canada) a national coalition that coordinates the

donation and transportation of food. Second, the corporatisation of food banks with national

food companies. This includes the creation of a National Food Sharing System6 that uses

shipping containers donated by NYK Line and Montreal Shipping, to transport food donated

by Quaker, Danone, Procter & Gamble, Campbell’s Soups, Kellogg’s and H.J. Heinz on

Canadian Pacific Railway and Canadian National Railway lines for free (Riches, 2002). In 2007,

the Canadian Association of Food Banks moved 8 million pounds of industry donated food

worth to $16 million dollars (Food Banks Canada, 2009). Third, food banks have now become

important players in the Canadian public safety net. The Canadian food bank network has

representation across the ten provinces and in most Canadian cities.

HungerCount 2007, an annual survey conducted by the Food Banks Canada on

emergency food services and food banks reveal that food bank use has increased by 91% since

the first survey was conducted in 1989. There are currently 673 food banks located in Canada

and 2,867 affiliated agencies (Canadian Association of Food Banks, 2008). The majority of food

banks, 75.8%, are located in Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia; there are 294 food banks in

Ontario.

The growth and proliferation of food banks represent the failure of the Canadian

state to provide basic needs for individuals. Income supplementation is agreed to be the best

way to deal with food insecurity, but this is not on the current agenda. “Food banks are the

voluntary back‐up to the failed Canadian social security net” (Riches, 2002).

Food banks were not designed to address the diversity of issues that contribute to

local food insecurity. The current institutionalisation of food bank organisations with corporate

donations as a major contributor of food supplies reflects their rigidity in adapting to changing

demographics and the need for culturally diverse food. Are food banks organisationally

constrained from changing their operations in light of Canada’s increase in diverse ethno‐

cultural communities? More importantly, are food bank organisations willing to change their

6 National Food Sharing System was created to share donations from national food companies among all Food Banks Canada and member food banks.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐26‐

operations to meet these needs? Food banks started off as a temporary solution to what has

now become a large permanent problem in the Greater Toronto Area and across the country.

How Food Bank Organisations Operate in the Area of Study

The food bank system is a network of organisations working towards delivering food

to individuals in need. Appendix B illustrates the organisation structure of food banks in

Canada. Food Banks Canada is responsible for supporting its members by acquiring food,

developing national partnerships, discussing the issue of hunger at a national scale and leading

research on the HungerCount Survey7.

The Ontario Association of Food Bank’s main goal is to acquire and distribute food

across Ontario. The Daily Bread, North York Harvest, York Region Food Network and The

Mississauga Food Bank are all member organisations of the Ontario Association of Food

Banks. All organisations have slightly different mandates and functions, but are responsible for

some degree of planning and overseeing of their member agencies (the individual food bank

agencies). These organisations offer a variety of other food relief programmes including

community kitchens, soup kitchens, school meals and community gardens. The Daily Bread’s

main role is to collect and distribute food to its 160 member agencies – 60 of which are food

banks – across Toronto. Their 60 food bank agencies do not all operate in the same manner

and are encouraged to adapt their services to reflect their users. The Daily Bread stresses their

advocacy for hunger issues, research and public awareness in regards to income insecurity8

(Daily Bread, 2009). It emphasises its role in pushing the government to re‐examine and

address poverty in a more direct way. As the Daily Bread enters into its first strategic planning

phase, it has indicated its desire to encourage its food banks agencies towards a community

development model rather than, the more commonly used charity model.

The North York Harvest is responsible for collecting and distributing food to 60

community programs – of which, 20 agencies function as food banks. Of these, 11 are faith‐

based organisations, 4 are run by colleges or universities and 5 are run by multi‐service

agencies. The North York Harvest is also responsible for advocacy in regards to food bank use

(North York Harvest Food Bank, 2009). The York Region Food Network is responsible for

coordinating regional food drives and functions as a networking agency for the eight food

7 Hunger Count Survey is conducted annually across Canada showing a breakdown of the socio‐economic profile of food bank users.

8 The Daily Bread indicates that they view lack of food as an issue of “income security” as opposed to “food security”.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐27‐

banks and various community gardens operating across York Region. It is not responsible for

the collection and distribution of food to member agencies but oversees their operations and

provides assistance where necessary. The York Region Food Network is involved in delivering a

local perspective and awareness on food security issues, and is also involved in research in

collaboration with the Daily Bread.

The Mississauga Food Bank9 is the largest food bank in Canada. It also acts as a

collector and distributor of food across the Peel Region. It has four member food banks which

serve about 4,000 people a month and about 6,000 people access their in‐house food bank.

The Mississauga Food Bank operates a “fair share” model emphasising the uniformity of

operations and procedures with all its member agencies (Mississauga Food Path, 2009). Figure

5.1. shows all of the food bank agency locations by food bank organisation across Toronto,

York and Peel Regions.

9 The Mississauga Food Bank was formerly known as Mississauga Food Path, its name was changed in early 2009.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐28‐

Figure 5.1: Food Bank Agency Locations in Toronto, Peel Region and York Region

Data Source: Statistics Canada, Profile for Census Metropolitan Areas, Tracted Census Agglomerates and Census Tracts, 2006 Census.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐29‐

Within this system, all four food bank organisations belong under the umbrella of

Food Banks Canada. All member organisations are bound to the Code of Ethics for the Food

Bank Community (Appendix C) and also the Ontario Association of Food Banks – Standards of

Operations. Both of these documents do not explicitly deal with racism or structural

discrimination.

Analysing the Annual HungerCount Survey – Are People of Colour Important?

I conducted an overview of the governing policies, organisational mandates, reports

and statistics of these organisations to gain a better understanding on how racism and race

was being viewed and portrayed by these organisations. None of the policies and regulations

explicitly state a mandate to work towards anti‐racist practices. Food Banks Canada’s main

research and advocacy is conducted through the annual HungerCount Survey. The Survey

collects information on immigrants, but not people of colour. It is used as a tool to gauge

hunger and all four food bank organisations participate in the survey. “If we are to figure out

how to significantly reduce hunger in Canada, we need to understand who is turning to food

banks for help, and why” (Food Banks Canada, 2008). Currently there is no advocacy on the

food security needs of people of colour or immigrants even as this is a growing segment of the

“new poor”.

6. Research Questions

The central question I was interested in addressing through my research was to

examine how food bank organisations, within the area of study contemplate race? I was also

interested to discover where are food bank agencies are located in relation to food‐insecure

people in the area of study.

7. Method

Qualitative Research – Interviews and Content Analysis

The qualitative research consists of nine semi‐structured interviews conducted in

February 2009 with staff and food bank directors (Table 7.1) across the area of study. The

interview questions were formulated by examining the work of the RACE Program at the

Western States Center (2001) (Appendix D). Through background research, four regional

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐30‐

central food collection, distribution and coordinating agencies in the area of study were

identified. I was interested in examining how food banks responded to and dealt with the idea

of race and the importance of anti‐racist practices within their organisations.

I conducted a content analysis of policy documents and research conducted by Food

Banks Canada, the Ontario Association of Food Banks and the Daily Bread and North York

Harvest. I was interested in examining if food insecurity issues faced by people of colour were

presented in their organisational policy statements and reported in their research.

Quantitative Research – Geographic Information Systems

I also used both basic statistical analysis10 and geographic information system to map

out the relationship between people of colour living below the low income cut‐off and the

location of food banks across the area of study11. I collected the information on the location of

food bank agencies from each food bank organisation and created a layer of data with food

bank locations that was mapped against various variables including Toronto’s 13 Priority

Neighbourhoods (2006)12, percentage of visible minorities and those below the low‐income

cut‐off. This analysis was focused on Toronto and not the area of study as a whole because of

the lack of food bank locations in Peel and York Region to provide a meaningful analysis of the

data.

8. Limitations

Speaking with Food Bank Users of Colour

One of the key limitations in this research was my inability to interview food banks

users directly. I feel the personal accounts of food bank users experiences is an important and

valuable addition in developing a greater understanding of the issues faced by people of

colour. I was able to gather second‐hand accounts on the perceived difficulties faced by food

bank users of colour from food bank directors and staff. Most of those interviewed perceived

the struggles faced by people of colour as the same as those faced by immigrants, while others

10 A basic correlation between people of colour and the prevalence for low income in Toronto revealed a significant strong

positive relationship between the two variables.

11 Please see footnote 5 for more information.

12 The 13 priority neighbourhoods identified by the Strong Neighbourhood Task Force have since been designated by the City

of Toronto’s community safety plan as areas that require focused investment to strengthen neighbourhood supports.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐31‐

emphasised that a visit to the food bank was difficult for all persons regardless of colour; most

organisations did not consider racism as a possible obstacle or barrier to food bank access for

people of colour. Further research is needed to better understand the experiences individuals

of colour go through when visiting a food bank.

Speaking with Food Bank Agencies

The member food bank agencies of the food bank organisations were not examined in

this study. Food bank agencies operate through faith‐based institutions, community

organisations or multi‐service agencies13. There is a lack of information on the demographics

of the food bank directors and volunteers of these individual agencies. My research has

indicated that most of these agencies operate in a top‐down approach. The top‐down

approach does not involve consultation or grassroots engagement with food bank users or

other community groups who may be using the services. Many agencies are also not always

representative of the populations they service in terms of their staff, volunteers, directors, and

board of directors. The governing ideologies and service goals are very different from

organisation to organisation. The examination of their relationship to communities of colour in

the services they provide is important in uncovering dimensions of discrimination that may

exist.

The Impact on Faith‐Based Organisations Delivering Services

The impact of the ideological underpinnings of church‐based organisations running

food bank agencies needs to be examined in the context of Toronto’s growing multi‐faith

communities of colour.

13 A multi‐service agency offers a number of services to individuals including prenatal classes, social and recreations

programmes, homework help clubs, community gardens, communal kitchens, nutrition programmes, counselling programmes and various other services.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐32‐

9. Key Findings14

Food Bank Locations

All four organisations indicated the struggles in locating food banks across the region;

these include finding suitable spaces for receiving, storing and distributing food, access by

public transportation, discreet locations to protect user anonymity, and costs. Most food banks

have traditionally been set up by churches and are clustered within the centre of the City (in

Figures 9.1, 9.2 and 9.3) where the food bank movement originated. There is no systematic

method to determine where new food banks will be placed. The location of new food banks is a

“haphazard,” process. The Daily Bread, North York Harvest and York Region Food Network all

indicate that new food banks are not selected on a needs analysis. The Mississauga Food Bank

also has indicated that different faith groups are now emerging and are interested in opening

food banks.

The key determinants of a new food bank agency include community capacity and

the willingness of an organisation (church group, non‐profit agency) to run the food bank

agency. The problem with this dependence on community capacity is that those communities

that are in most need of a food relief programmes often go underserviced as they lack the

initial infrastructure to host a food bank. Those communities without local capacity also have

high incidences of racialised poverty (including Scarborough, indicated by the blue area in

Figure 9.3). Lack of community capacity has been the main obstacle in setting up food bank

agencies in the inner suburbs.

The Daily Bread indicates it looks at Toronto’s 13 priority neighbourhoods when

examining food bank locations but Figures 9.1 and 9.2 indicate a lack of food bank agencies

especially within Dorset Park, Eglington East – Kennedy Park and Scarborough. The Daily

Bread and North York Harvest have acknowledged this service gap in the cities inner suburbs.

Figure 9.3 indicates people of colour with low incomes are more likely to be without a food

bank within their neighbourhoods compared to white people with low incomes.

14 Please see Appendix G for a summary table of my findings.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐33‐

Figure 9.1: Food Bank Agency Locations and Toronto’s 13 Priority Neighbourhoods (2006)

Data Source: Statistics Canada, Profile for Census Metropolitan Areas, Tracted Census Agglomerates and Census Tracts, 2006 Census, City of Toronto, Toronto Neighbourhoods (2003), Neighbourhood Services Department.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐34‐

Figure 9.2: Food Bank Agency Locations, Percentage of Population Below the Low Income Cut‐off (2005), Visible Minority Percentages and Toronto’s 13 Priority Neighbourhoods (2006)

Data Source: Statistics Canada, Profile for Census Metropolitan Areas, Tracted Census Agglomerates and Census Tracts, 2006 Census, City of Toronto, Toronto Neighbourhoods (2003), Neighbourhood Services Department.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐35‐

Figure 9.3: Food Bank Agency Locations and Category of Low Income (2005) and Visible Minority Percentages and Toronto’s 13 Priority Neighbourhoods (2006)

Data Source: Statistics Canada, Profile for Census Metropolitan Areas, Tracted Census Agglomerates and Census Tracts, 2006 Census, City of Toronto, Toronto Neighbourhoods (2003), Neighbourhood Services Department.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐36‐

People of Colour and Food Bank Use

At the moment, none of the food bank organisations studied collects information on

the number of people of colour using their services. The Daily Bread is responsible for the

administration of the HungerCount survey, which is conducted across the area of study. This

survey collects a variety of information including immigrant status. Immigrant status is

considered to be a “good enough” indicator for assessing the number of people of colour

accessing food banks. There is also a general resistance to collecting this information within

their survey because of the difficult position surveyors would be placed in when collecting such

data. More importantly the validity of collecting race‐based statistics was questioned. There

was concern about the relevance of race‐based statistics, potential controversy, and debate

about the usefulness of such data. The Daily Bread indicated concerns that potential partners

and funders would object to collecting this information and that there would be resistance

among member food bank agencies.

Although there are no statistics collected on people of colour, anecdotally all four

organisations can affirm they have seen an increase in the number of food banks users who are

people of colour. One interviewee commented, “Until this recession hit most of our new clients

were new immigrant, generally from South Asia and Latin America”.

Services for People of Colour

In general there is a lack of previous thought given to how food banks can gear

services towards people of colour; this is reflected in the lack of services offered to people of

colour. This is because people of colour are perceived to face all of the same problems as white

food bank users. When asked if people of colour faced any unique barriers in accessing the

food bank it was mainly their immigrant status and cultural difference that were listed as

barriers and not racism, as described by this Executive Director:

I wouldn’t put it down to people of colour, I would call it as newcomers for two reasons.

First of all language is a barrier, people don’t know where to come...Secondly, from a

number of countries there is a large stigma in asking for charity...I feel there are a whole

number of people [immigrants] who need to access our services because they don’t know

about our services and if they did, their pride would not allow them to access.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐37‐

This sentiment was also expressed by another Executive Director:

Firstly it is a cultural barrier [food bank use]. It is not something that they have brought

with them: the idea to go to a food bank. It’s a fairly North American solution to things.

There are two main parts to this assumption, first is the denial of race as an important factor

within their services (colour‐blindness) and second the assumption that immigrants are

culturally averse to food banks. The barriers that people of colour face in accessing food banks

are therefore placed on the individual (their language and their culture) and that the services

they are offering are inappropriate or a deterrent all together. Assertions that people of colour

are not unique in the services they required compared to white food banks users is a way of

evading the issues and racism faced by people of colour.

The Daily Bread, North York Harvest and York Region Food Network all indicate it is

important to offer unique programmes and services to people of colour while the Mississauga

Food Bank did not:

Interviewer: Do you think it is valuable to offer programmes towards people of

colour?

The Mississauga Food Bank: No... it’s not on our strategic radar... I don’t know of an organisation

that says we cater to people of colour.

Providing services geared towards people of colour is not seen as a priority for this interviewee.

As a service provider it is logical protocol to measure, assess, and reflect the demographics

that are being served by one’s organisation. People of colour lack the legitimacy as a

demographic group within food bank organisations. The interviewee’s use of the word “cater”

has the connotations that people of colour are making special demands outside of their rights,

thus, people of colour are equated to a special interest.

There was a great level of confusion in terms of the types of programmes food bank

organisations could offer to people of colour within the food bank context. One interviewee

indicated this confusion by stating, “I think its valuable [but] in this particular sector [food

banks] off the top of my head I cannot think of a value.” Most food bank organisations opposed

to the idea of having food banks geared towards different ethno‐cultural groups. The majority

of the services geared towards people of colour include some culturally diverse food,

translation of materials and some multi‐lingual staff and volunteers. Many times, superficial

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐38‐

cosmetic measures such as providing translation materials, are seen as great achievements

without really working towards addressing the issues of racism at an organisational level and

the experiences of people of colour assessing those services (Henry and Tator, 2005).

Culturally Appropriate Food

The ability to provide culturally appropriate food within food bank agencies was an

important area of my examination. Access to culturally appropriate food is an important

measure of food security (Brink, 2002). Food bank agencies in the region indicate a lack of

resources in their ability to provide culturally appropriate food. The Mississauga Food Bank

offers halal meat at times, and the Daily Bread runs a Staples programme, purchasing food

such as flour, rice, beans, tomato paste, for food bank agencies interested in distributing these

items instead of donated food, but this programme is subject to budgetary constraints.

Culturally appropriate food is seen as a luxury and hassle, as one interviewee explained:

We have a shelter that was dealing entirely with Muslim women and they have a cook and

nutritionist on site who prepares the meals but they won’t eat the food. Unless they have

seen it cooked from start to finish, the women won’t eat it. They have to make sure it’s

been properly handled all the way through the process. Because of that they won’t take

any of the food that we have to offer. Dealing with that client base is expensive.

There is an expectation within the food bank community that clients should adapt to the food

offered at the food bank. One interviewee explained, “We are at the mercy of what food gets

donated to us. At the end of the day we are a food bank and not a cultural grocery store.”

There is a great deal of emphasis placed on the need for individuals using the food bank to

accept the food that is available. This interviewee also emphasised the importance of adapting

to the food in whichever region the food bank users might find themselves:

In [northern Ontario] they eat moose. The Thunder Bay food bank deals in moose meat,

in tractor truck loads, that’s what they eat in that neck of the woods, even if you’ve arrived

from Iraq and you happen to find yourself in [a] Thunder Bay [food bank]...you’re going to

be served moose meat.

Culturally appropriate food is not a high priority for most food bank organisations because of the

perceived obstacles in obtaining it, for example the lack of culturally relevant food being donated.

Therefore culturally appropriate food is viewed as a bonus, as opposed to a necessity.

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐39‐

Through my interview with the one Executive Director there was concern expressed on

the gap between individuals living in poverty in the Region and the number of people acquiring

emergency food through their partner food banks. I suggested the unavailability of culturally

acceptable food may act as a deterrent to food bank access in the Region but this was firmly

discounted as a viable reason by the interviewee who indicated confidently:

I don’t believe for one second that’s why people are not accessing food banks, a loaf of

bread is a loaf of bread and no matter what culture you are, you’ll have a loaf of bread…its

not because you don’t have my kind of food.

Food banks are in the business of distributing food, that is their main service, I found it

interesting that they do not consider how to accommodate user preferences, since almost half

of Daily Bread users are immigrants, many whom are new immigrants. Furthermore almost

three‐quarters of the food bank users of the five largest food bank agencies in North York are

immigrants; these are considerably large numbers which cannot be ignored. Despite these

numbers there remains a strong belief that food‐insecure users should not be placing demands

on the type of food they want to eat, one interviewee commented:

If you’re hungry and starving...I hate to say it but you know, you’re new to this country,

you are refugee, or you’re poor, or you’re in a bad situation, you’re been given donated

food. If you want to eat you’re going to have to adjust.

This resistance to change combined with the lack of initiative on working to provide more

culturally appropriate food intensifies the alienation of food bank users of colour.

People of Colour Staff and Volunteers

The four food bank organisations were varied in their commitment to hiring staff of

colour and recruiting volunteers of colour. In general most food bank agencies showed an

interest in hiring people of colour staff and volunteers. The Daily Bread Food Bank was the only

organisation with an official policy to proactively hire people of colour. North York Harvest is

interested in hiring more people of colour but at the moment does not have any plans or

polices currently in place to pursue this direction.

The Mississauga Food Bank presents a contrast to their partners within the region.

There was a lack of understanding and belief that there was a value to hiring people of colour

staff. One interviewee commented “we don’t hire a visible minority just so we have a visible

minority.” The interviewee in charge of recruiting volunteers emphasised the irrelevancy of

having volunteers of colour:

Approaches to People of Colour and Food Bank Use in the City of Toronto, Peel Region and York Region ‐40‐

I do not go out of my way to recruit diverse volunteers, we post volunteer opportunities,

the process is people apply, they are assessed on many different levels and I can

guarantee you the very last thing I look at is their ethnic background.

Henry and Tator (2005) explain that within human service agencies, the number staff members

that are people of colour demonstrates a commitment to providing better services to people of

colour and a commitment to multiculturalism and anti‐racism.

Anti‐racism Training

The Daily Bread places an importance on anti‐racism training for its own staff.

Information on Daily Bread’s food bank agencies is less clear, as they operate autonomously.