Adventuresome Aussie dance company Lucy Guerin Inc. explores info

Applying the Clinical Pathways Concept to Diabetes Care ...€¦ · Richard G Stefanacci, DO, MGH,...

Transcript of Applying the Clinical Pathways Concept to Diabetes Care ...€¦ · Richard G Stefanacci, DO, MGH,...

Issue Highlights

S5. EDITORIALExploring the Potential of Clinical Pathways for DiabetesWinston Wong, PharmD

S7. SPECIAL ARTICLEDiabetes Clinical Pathways: Going Beyond Treatment DecisionsRichard G Stefanacci, DO, MGH, MBA, AGSF, CMD; Scott Guerin, PhD

S10. SPECIAL ARTICLEThe Solution to More Effective Diabetes Management: Better Products or Better Programs? Larry Blandford, PharmD

www.jcponline.comLLC

, ™

December 2016 Vol 2, Suppl 1

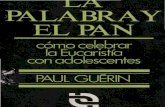

Applying the Clinical Pathways Concept to Diabetes Care: Challenges and Future Directions

1216_JCP_DiabetesSupp_Cover.indd 1 12/2/16 4:40 PM

Are you ready to shape the future of

healthcare?

The Journal of Clinical Pathways is currently accepting articles presenting data,

research, insight, and perspectives on approaches to care that deliver the greatest

clinical benefit, the least toxicity and the highest level of value.

Contribute to the conversation.Submit your article at jcponline.com.

JCPADs.indd 7 4/19/16 11:55 AM

www.jcponline.com December 2016 • Journal of Clinical Pathways S1

EDITORIAL STAFF ASSOCIATE EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Kara A Rosania, MS

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Cameron Kelsall, MA

ASSISTANT WEB EDITOR Zachary Bessette

BUSINESS STAFF VICE PRESIDENT, GROUP PUBLISHER Christopher Ciraulo [email protected]

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR, NATIONAL ACCOUNTS, MANAGED MARKETS Jeff Hennessy, Jr. [email protected]

NATIONAL ACCOUNTS MANAGER Sai Niyogi [email protected]

CLASSIFIED ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE Joseph Miller [email protected]

CIRCULATION MANAGER Bonnie Shannon [email protected]

HMP COMMUNICATIONS, LLC PRESIDENT Bill Norton

SENIOR DIRECTOR OF MEDICAL COMMUNICATIONS Lisa A Tomaszewski, PhD

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Vic Geanopulos

DESIGNER Alicia Indico

PRODUCTION/CIRCULATION DIRECTOR Kathy Murphy

AUDIENCE DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Bill Malriat

HMP COMMUNICATIONS HOLDINGS, LLC CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Jeff Hennessy

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Mitch Codkind

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT OF SHARED SERVICES Anthony Mancini

CONTROLLER Meredith Cymbor-Jones

SENIOR DIRECTOR OF MARKETING Kelly Koczak McCurdy

DIRECTOR OF E-MEDIA AND IT Tim Shaw

SENIOR MANAGER, IT Ken Roberts

© 2016, HMP Communications, LLC, (HMP). All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part prohibited. Opinions expressed by authors, contributors, and advertisers are their own and not necessarily those of HMP Communications, the ed-itorial staff, or any member of the editorial advisory board. HMP Communications is not responsible for accuracy of dosages giv-en in articles printed herein. The appearance of advertisements in this journal is not a warranty, endorsement, or approval of the products or services advertised or of their effectiveness, quality, or safety. HMP Communications disclaims responsibility for any injury to persons or property resulting from any ideas or prod-ucts referred to in the articles or advertisements. Content may not be reproduced in any form without written permission. For information on rights, permission, reprint, and translation, visit www.hmpcommunications.com.

Features

S5 EDITORIALExploring the Potential of Clinical Pathways for DiabetesWinston Wong, PharmDAs the prevalence of diabetes in the United States grows, and as people with diabetes live longer with the disease, there is a need for improved health services to better man-age the disease as well as to control its associated costs. This effort primarily consists of improved education and support for diabetes self-management as well as greater standardization of diagnostic and treatment practices for diabetes. While these initia-tives are currently being supported by programs and guidelines developed by leading diabetes associations, clinical pathways provide an opportunity to aid the implementa-tion of evidence-based practices for patients with diabetes in order to improve control of the disease, reduce the incidence of complications, and contain health care costs.

S7 SPECIAL ARTICLEDiabetes Clinical Pathways: Going Beyond Treatment Decisions Richard G Stefanacci, DO, MGH, MBA, AGSF, CMD; Scott Guerin, PhDAs a result of new value-based systems, quality measures are finding greater prominence in the development of diabetes guidelines. Efficiency gaps in prevention and care con-tribute to poor reimbursement in the management of chronic conditions such as diabe-tes. It is for this reason that clinical pathways may be utilized in diabetes care, building on the foundation of the recognized guidelines while taking into consideration the cultural landscape of the individual patient, which may perpetuate low health literacy. Innovative tools and products may help patients in their struggle to achieve optimal disease management.

S10 SPECIAL ARTICLEThe Solution to More Effective Diabetes Management: Better Products or Better Programs?Larry Blandford, PharmDThe need for effective strategies in the management of diabetes continues to increase in urgency as costs swell and a path to successful management remains elusive. These facts have all contributed to a deluge of products being developed in the diabetes care space. Although more products offer new management approaches and a greater pos-sibility for individualized care, these options do not guarantee improved quality of care if they are not incorporated properly into an individual’s care strategy. This piece focuses on the breadth of the diabetes market as well as the opportunities available for real advancement in diabetes care.

CONTENTSDecember 2016; Volume 2, Supplement 1

jcp1216_Diabetes_TOC.indd 1 12/5/16 5:06 PM

Supplements to Journal of Clinical Pathways adhere to the International Council of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) Recommendations for the Conduct, Re-porting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals. Supple-ments, theme issues, or special series published as a separate issue of the journal or as part of a regular issue are collections of papers intended to highlight specific issues or topics related to the journal’s editorial mission and scope. Because these may be funded by sources other than the journal’s publisher, supplements to Journal of Clinical Pathways adhere to the following principles:

• The journal editor takes full responsibility for the policies, practices, and content of supplements, including complete control of the decision to select authors, peer reviewers, and content for the supplement. Editing by external funding organizations is not permitted.

• The journal editor retains the authority to send supplement manuscripts for external peer review and to reject manuscripts submitted for the supple-ment with or without external review.

• Any external sources of the idea for the supplement, sources of funding for the supplement’s research and publication, or products of the funding source related to content considered in the supplement will be clearly stated in the introductory material.

• Advertising in supplements follow the same policies as those of the primary journal.

• Journal and supplement editors must not accept personal favors or direct remuneration from sponsors of supplements.

• Secondary publication in supplements (republication of papers published elsewhere) will be clearly identified by the citation of the original paper and by the title.

• The same principles of authorship and disclosure of potential conflicts of interest that apply to the primary journal are applied to supplements.

supplement policy statement

S2 Journal of Clinical Pathways • December 2016 www.jcponline.com

STANDARDS FOR SUPPLEMENTS TO JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PATHWAYS

EDITORIAL CORRESPONDENCE should be addressed to Kara A. Rosania, Journal of Clinical Pathways®, HMP Communications, 70 E. Swedesford Road, Suite 100, Mal-vern, PA 19355. Telephone: (800) 237-7285 or (610) 560-0500, ext. 4104. Fax: (866) 800-4236. E-mail: [email protected]

ADVERTISING QUERIES should be ad-dressed to Sai Niyogi, Associate Nation-al Accounts Manager, Journal of Clinical Pathways®, HMP Communications, 70 E. Swedesford Road, Suite 100, Malvern, PA 19355. Telephone: (610) 560-0500, ext. 4126. Fax: (610) 560-4146. E-mail: [email protected]

SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION The Journal of Clinical Pathways® is sent with-out charge to qualified clinical pathways professionals in the U.S. All other subscrip-tion rates are as follows: United States: $570.00 annual, $95.00 single issue. Call 1-800-237-7285, ext. 4246 or Email: [email protected].

DISPLAY AND CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING: Joseph Miller, Classified Account Execu-tive, HMP Communications, 70 E. Swedes-ford Road, Suite 100, Malvern, PA 19355, Telephone: (800) 237-7285 or (610) 560-0500, ext. 4308. Fax: (610) 560-0501. E-mail: [email protected]

Journal of Clinical Pathways: The Foundation of Value-Based Care® (ISSN 2380-9604) is published ten times per year by HMP Communications, 70 E. Swedesford Road, Suite 100, Malvern, PA 19355. Telephone: (800) 237-7285, Fax: (610) 560-0501.

HMP Communications LLC (HMP) is the authoritative source for comprehen-sive information and education servicing healthcare professionals. HMP’s prod-ucts include peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed medical journals, nation-al tradeshows and conferences, online programs, and customized clinical pro-grams. HMP is a wholly owned subsid-iary of HMP Communications Holdings LLC. Discover more about HMP’s prod-ucts and services at: www.hmpcommu-nications.com.

For information on obtaining copies, re-prints, and permission to use any of our articles or information contained therein, please visit www.jcponline.com.

LLCan HMP Communications Holdings Company

,™

1216SupplementPolicy.indd 2 12/5/16 5:07 PM

www.jcponline.com December 2016 • Journal of Clinical Pathways S3

Brian D Bastean, PharmDDirector, Value Based Cancer CareJanssen Scientific Affairs, LLCHorsham, PA

Alex W Bastian, MBAVice President, GfK Market AccessStrategic Advisor, ASCO Value In Cancer Task ForceSan Francisco, CA

Larry Blandford, PharmDExecutive VP and Managing PartnerPrecision AdvisorsGladstone, NJ

Terry A Cronan, PhDProfessor of PsychologyPsychology Department, San Diego State UniversitySan Diego, CA

Aymen Elfiky, MD, MPH, MScAttending Physician, Medical OncologyDana Farber Cancer InstituteBrigham and Women’s HospitalHarvard Medical SchoolBoston, MA

Bruce A Feinberg, DOVice President/Clinical Affairs Chief Medical Officer Cardinal Health Specialty SolutionsDublin, OH

Willard Harms, MD, MBAVice President of Medical AffairsBlue Cross Blue ShieldColumbia, SC

Dwight Heron, MD, FACRO, FACRVice Chairman of Clinical Affairs, UPMCMedical Director, Via OncologyPittsburg, PA

David Hughes, BSNAssociate Director, Clinical PathwaysSeattle Cancer Care AllianceSeattle, WA

Swapna Karkare, MSSenior Consultant, Health Economics and Outcomes ResearchReal-World Evidence SolutionsIMS HealthDeerfield, IL

Edward Li, PharmD, MPH, BCOPAssociate Professor, Pharmacy PracticeUniversity of New England College of PharmacyPortland, ME

Maria Lopes, MD, MSChief Medical OfficerMagellan Rx ManagementNewport, RI

Gary Owens, MDPresident, Gary Owens AssociatesGlen Mills, PA

Patti Peeples, RPH, PhDCEO, HealthEconomics.comPrinciple Researcher, HE InstitutePonte Vedra Beach, FL

Margaret B Rausa, PharmDVice President, Medical Oncology and Specialty Drug ManagementeviCore HealthcareBluffton, SC

Edward J Stepanski, PhDChief Operating Officer, Vector OncologyProfessor of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine,University of Tennessee Health Sciences CenterMemphis, TN

EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD

editor-in-chiefWinston Wong, PharmD

PresidentW-Squared GroupLongboat Key, FL

jcp1216EditBoard.indd 3 12/6/16 12:49 PM

The pathway for staying informed.

Visit jcponline.com. Sign up for enews.

JCPADs.indd 11 4/19/16 12:05 PM

editorial

www.jcponline.com December 2016 • Journal of Clinical Pathways S5

As the prevalence of diabetes in the United States grows, and as people with diabetes live longer with the disease, there is a need to improve education and support for diabetes self-management as well as standardization of diagnostic and treatment practices for diabetes. While these initiatives are currently being supported by pro-grams and guidelines developed by leading diabetes as-sociations, clinical pathways provide an opportunity to aid the implementation of evidence-based practices for patients with diabetes in order to improve control of the disease, reduce the incidence of complications, and contain health care costs.

Approximately 1.4 million Americans are diagnosed with diabetes every year, according to the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention.1 As of 2012, the prevalence of diabetes in the United States was estimated at more than 29 million, or 9.3% of the population. Diabetes is particularly common among aging Americans; more than one-quarter of those aged 65 years and older has diabetes. At the same time, prediabetes is becoming more common: from 2010 to 2012, the number of Americans aged 20 and older with prediabetes grew from 79 million to 86 million. If current trends continue, the prevalence of diabetes is projected to double for all US adults by 2050.1

Type 2 diabetes is the most common form of diabetes, ac-counting for 90% to 95% of diagnosed cases in US adults.1 In addition to the core symptom of insulin resistance, diabetes can lead to health complications including heart disease, stroke, kid-ney disease, blindness, and amputation. As people with type 2 diabetes live longer, there is a need for improved health services to better manage the disease as well as to control its associated costs, which have been estimated as totaling $176 billion.1

a place for clinical pathwaysDiabetes management has become a multifaceted treatment pro-cess, with the common goal of controlling serum glucose levels and preventing secondary complications. Interventions consist of behavior modifications, patient engagement, and medications. Environmental and behavioral risk factors play an important role in determining the most effective interventions. For example, medication selection is far beyond simply just choosing a rep-

resentative medication from a therapeutic class at random, but rather choosing the most appropriate medication based upon the patient’s risk factors. Clinical pathways firmly have a place in diabetes care by: (1) assisting to systematically evaluate the patient’s clinical presentation and risk factors; (2) choosing the most appropriate behavioral and medication interventions; and (3) providing a timeline for patient follow-up and monitoring. In short, clinical pathways will assist in the coordination of care and follow-up.

successful diabetes management programsDiabetes management requires a multidisciplinary approach, which includes medication to reduce glucose levels—insulin, oral medication, or a combination of both—as well as health-ful eating, regular physical activity, and management of cormor-bid conditions.1 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) has published Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes in order to provide primary care providers with current, evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with all forms of diabetes.2 Recommended initial care consists of Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support, medi-cal nutrition therapy (MNT), physical activity education, smok-ing cessation counseling, guidance on routine immunizations, psychosocial care, patient self-monitoring of blood glucose, and regular hemoglobin A

1c (HbA

1c) testing.

Due to the risks associated with hypoglycemia, medication adherence, and glucose monitoring, there is a large focus on im-proving patients’ self-management of their disease. The ADA, in conjunction with the American Association of Diabetes Educa-tors, have published National Standards for Diabetes Self-Man-agement Education and Support, which are designed to define quality diabetes self-management. This clarification assists diabe-tes educators in providing evidence-based education and self-management support.3 The Standards are intended to emphasize that the person with diabetes bears the primary responsibility for managing their condition on a day-to-day basis.

One example of a diabetes management program recognized by the ADA as a quality diabetes self-management education program that meets the National Standards for Diabetes Self-Management Education is at University Medical Center of Princeton.4 The program consists of a multidisciplinary team of

Exploring the Potential of Clinical Pathways for DiabetesWinston Wong, PharmD

affiliations: W-Squared Group, Longboat Key, FL

disclosures: The author reports no relevant financial relationships.

jcp1216_Diabetes_Wong.indd 5 12/6/16 1:35 PM

editorial

S6 Journal of Clinical Pathways • December 2016 www.jcponline.com

diabetes specialists, includes a staff of Certified Diabetes Educa-tors, who work closely with patients, their primary care physi-cians, and other health care providers. Services include individual and group education sessions by registered nurses and dietitians, medication management, blood glucose monitoring instruction, insulin pump training, community outreach programs, diabetes care and management for pre-pregnancy/conception and dur-ing pregnancy, MNT/nutrition education and meal planning, weight management, stress management and wellness programs, and professionally facilitated monthly support groups.

When a patient is hospitalized at University Medical Cen-ter of Princeton, the Certified Diabetes Educators collaborate with the admitting physician and inpatient health care team to ensure optimum care. Upon discharge, a patient is referred to the comprehensive outpatient Self-Management Education Program for additional instruction, and health care providers from the program continue to follow up with the patient to inquire about their progress and any ongoing needs, encourag-ing patients to make annual follow-up visits to the program.

A growing arena in diabetes management is telemedicine services, which can range from simple reminder messaging to more comprehensive monitoring where patients can upload their glucose levels measured with a home meter, as well as other monitoring metrics such as medications, dietary habits, activ-ity level, and medical history. Providers can review the data and provide feedback regarding medication adjustments and lifestyle modifications. In a recent review of over 3600 citations of the use of telemedicine in diabetes care, it was concluded that tele-medicine maybe be a useful supplement to the usual clinical care, using the HbA

1c as the indicator of clinical impact.5 The

authors also concluded that telemedicine interventions appeared to be most effective when they were able to engage the patients using a more interactive interface.

guidelines for diabetes treatmentIn addition to self-management, the fast-paced growth of avail-able medication options for diabetes warrants improved guid-ance for physicians in their decisions regarding pharmacological therapy. The 2016 ADA Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes provide a comprehensive list of available glucose-lowering agents to guide individualized treatment choices. Metformin is consid-ered the preferred initial pharmacological agent for patients for whom it is tolerated and not contraindicated. Further treatment with a secondary agent—sulfonylurea, thiazolidinedione, dipep-tidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 in-hibitor, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, or insulin—is based on whether patients are symptomatic and whether they are able to achieve glycemic goals. The guidelines recommend taking a “patient-centered approach” to dual therapy selection based on considerations including efficacy, hypoglycemia risk, weight, potential side effects, and costs.2 An algorithm for treat-ment selection based on these considerations, as well as for selec-tion of triple therapy or combined injectable therapy regimens, is also provided in the form of a flow chart.2

Another approach that has been taken to guiding treatment decisions for patients with type 2 diabetes has been developed by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) together with the American College of Endocrinology (ACE). The AACE/ACE Diabetes Management Algorithm includes guidance on lifestyle therapy, management of complications, glycemic control, insulin dosing, consideration of risk factors, and potential adverse events associated with antidiabetic medica-tions.6 Similar to the ADA guidelines, the AACE/ACE Diabetes Management Algorithm also includes recommendations for the selection of glucose-lowering agents. However, the Algorithm goes further by ranking different types of agents for monother-apy, dual therapy, and triple therapy on the basis of the evidence to support each type of drug. Thus, the AACE/ACE approach is more similar to clinical pathways than the ADA, which offers more straightforward clinical practice guidelines.

Additional models for clinical pathways for diabetes have been developed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).7 Major changes to the routine manage-ment of diabetes have been noted since 2004. In response, NICE updated several pathways in 2016, recommending ag-gressive HbA

1c targets.7 The guidance stresses a patient-cen-

tered approach, including behavior and medication interven-tions, steps for evaluation, and treatment decisions based upon the findings. It is the intent of the guidance to reduce the im-pact of secondary complications.7

conclusionAs we consider the expanding role of clinical pathways beyond that of medication treatment options, representing a true mul-tidisciplinary approach, the link of clinical pathways to diabe-tes management become clear. All facets of diabetes manage-ment can become integrated into a clinical pathway, including clinical presentation and evaluation, treatment intervention and patient engagement, and monitoring and follow-up. The pathway becomes a tool to systematically treat the patient so that processes become standardized and consistent, enabling us to achieve better outcomes and control care costs.

References1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014 National Diabetes Statistics Report.

CDC website. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/2014statisticsreport.html. May 15, 2015. Accessed November 23, 2016.

2. American Diabetes Association Position Statement: Standard of Medicare Care in Diabe-tes—2016. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(suppl 1):S1-112.

3. Haas L, Maryniuk M, Beck J, et al. National Standards for Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(suppl 1):S144-S153.

4. University Medical Center of Princeton. Diabetes Management Program. http://www.princetonhcs.org/phcs-home/what-we-do/university-medical-center-of-princeton-at-plainsboro/what-we-do/additional-clinical-care--services/diabetes-management-pro-gram.aspx. Accessed November 23, 2016.

5. Faruque LI, Wiebe N, Ehteshami-Afshar A, et al. Effect of telemedicine on glycated he-moglobin in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials [pub-lished online October 31, 2016]. CMAJ. doi:10.1503/cmaj.150885.

6. Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the Comprehensive Type 2 Diabetes Management Algorithm—2016. Executive Summary. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(1):84-113.

7. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE pathways—diabetes overview. http://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/diabetes. Updated November 22, 2016. Ac-cessed November 23, 2016.

jcp1216_Diabetes_Wong.indd 6 12/6/16 12:38 PM

special article

www.jcponline.com December 2016 • Journal of Clinical Pathways S7

Diabetes guidelines increasingly go beyond treatment recommendations to take into account quality measures for diabetes care that exist within new value-based sys-tems, addressing the roles and responsibilities of diabetes clinical stakeholders and incorporating the use of in-novative patient engagement tools. Because gaps in dia-betes prevention and care relate to poor reimbursement for managing chronic conditions, clinical pathways for diabetes could build on diabetes care guidelines by ad-dressing cultural differences and low health literacy of patients and the need for innovative tools and products to help patients overcome barriers to managing their diabetes.

Diabetes guidelines today involve much more than simply identification of the “right” treatment. Instead, today’s dia-

betes guidelines are required to take into account the increas-ing quality measures, roles and responsibilities of diabetes clinical stakeholders, and the use of innovative patient engagement tools that all exist within new value-based systems. These systems in-clude accountable care organizations (ACOs), patient-centered medical homes, and comprehensive practice care, in addition to new alternative payment systems that may be developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

Many of the quality measures for diabetes are derived from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of Care, which started with general practice recommendations and defi-nitions about quality and expanded to develop specific clinical goals related to blood glucose, blood pressure, and lipid manage-ment. This produced care measures established through a collab-oration of quality-based organizations which eventually became known as the Comprehensive Diabetes Care measure used in Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS).

Stakeholder organizations continue to refine approaches to diabetes care. For example, the National Diabetes Quality Im-provement Alliance makes recommendations to the National Quality Forum regarding improvements in diabetes measures that are incorporated into many pay-for-performance quality programs.1

HEDIS data show that diabetes care is improving over time, but slowly. Currently, 21 million Americans have the disease, but almost half of them do not keep their blood glucose under control.2 The National Committee for Quality Assurance sug-gests that gaps in diabetes prevention and care relate to poor reimbursement for managing chronic conditions. Also, many physicians simply do not have the time or skills to teach patients behavioral strategies. There’s also a lack of programs that address cultural differences and low health literacy of patients, not to mention a need for innovative tools and products to help pa-tients overcome barriers to managing their diabetes. As a result, diabetic guidelines require much more than direction on the right treatments.3

goals of therapyWhile the goals of therapy for all diabetic patients are essentially the same, namely to avoid the consequences from both over and under treatment, the specific target can be very different for each patient. For older adults, those goals are mainly focused on avoiding hypoglycemic events which requires less aggressive glycemic control (Table 1).

The American Geriatrics Society recently recommended to avoid using medications to achieve hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) < 7.5% in most adults aged 65 years and older; moderate con-trol is generally better.4 This recommendation was based on the fact that there is no evidence that using medications to achieve tight glycemic control in older adults with type 2 diabetes is beneficial. Among nonolder adults, except for long-term reduc-tions in myocardial infarction and mortality with metformin, using medications to achieve glycated hemoglobin levels < 7% is associated with harms, including higher mortality rates. Tight control has been consistently shown to produce higher rates of hypoglycemia in older adults.4

Given the long timeframe to achieve theorized microvascular benefits of tight control, glycemic targets should reflect patient goals, health status, and life expectancy. Reasonable glycemic tar-gets would be 7.0% to 7.5% in healthy older adults with long life expectancy, 7.5% to 8.0% in those with moderate comorbidity and a life expectancy <10 years, and 8.0% to 9.0% in those with

Diabetes Clinical Pathways: Going Beyond Treatment DecisionsRichard G Stefanacci, DO, MGH, MBA, AGSF, CMD; Scott Guerin, PhD

affiliations: The Access Group, Berkeley Heights, NJ.

disclosures: Dr Stefanacci is the chief medical officer for The Access Group, a professional services firm focusing on managed markets in the pharmaceutical industry. He has received speaking fees from Allergan and Pfizer; serves on advisory boards for AbbVie, the ASCP Foundation, and the AMDA Foundation; and has provided consult-ing services to AstraZeneca, Baxter, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Leo Pharma.

Dr Guerin is the senior director for Government Policy System and Analytics for The Access Group.

jcp1216_Diabetes_Stefanacci.indd 7 12/5/16 5:11 PM

special article

S8 Journal of Clinical Pathways • December 2016 www.jcponline.com

multiple morbidities and shorter life expectancy. The setting of more appropriate targets can go a long way in reducing hypo-glycemic events.4

As a corollary to medication treatment for diabetes, many facilities are still using modified diets and dietary restrictions for their diabetic residents. Nutrition has consistently been ranked as highly important to residents in the long-term care contin-uum. The American Dietetic Association published a position paper in 2010 on liberalization of diets in long-term care, stating: “There is no evidence to support prescribing diets such as no concentrated sweets or no sugar added for older adults living in health care communities, and these restricted diets are no longer considered appropriate.”5 Most experts agree that using medica-tion rather than dietary changes can enhance the joy of eating and reduce the risk of malnutrition for older adults in health care communities. For many older adults residing in health care communities, the benefits of less-restrictive diets outweigh the risks. The use of a more liberalized approach produces several benefits, including better intake, lower incidence of unintended weight loss, more consistent blood glucose levels, and, perhaps most important, quality of life for residents. These individual-ized goals of therapy developed by these associations need to be incorporated into diabetes care guidelines.

population-based careIn a study of 23,000 diabetic patients, most of the quality and pay-for-performance programs they were participating in centered on poorly controlled patients with HbA1c ≥ 9%. However, this analysis showed that the typically targeted high-risk population was highly dynamic, had sizable turn-over and—importantly—was a relatively small subpopulation of patients.6

Two other studies showed that increased interactions with a clinical pharmacist; regular primary care visits; and screenings for blood glucose, cholesterol levels, kidney function, and eye exams that include some incentives can significantly affect dia-betes management in patient populations. In turn, this can lower health risks and reduce related health care costs.7,8

As the management of diabetes care improves due to con-tinuing efforts to refine quality measures, implementation of pay-for-performance programs, and the development of inno-

vative products, additional advancements can be made by simply expanding the scope of the target populations, increasing dis-cussions with diabetic patients, and implementing appropriate screening. Together, these are a leap forward for disease manage-ment into true population health.

value-based diabetes programsBecause of the prevalence of uncontrolled diabetes and related health care costs, several value-based programs seek to monitor and manage key factors of the disease. For example, the Medi-care Advantage Five Star Rating program provides bonuses to Medicare Advantage plans for several therapeutic areas, with four measures related to diabetes being evaluated: eye exam, kidney disease monitoring, blood sugar control, and adherence to dia-betes medications.9

Medicare ACO models provide bonuses or penalties based on performance on quality measures and cost controls. These quality measures include HbA1c control, eye exams, in addition to an all-cause unplanned admission rating for patients with dia-betes.10 An interesting point pertaining only to Medicare ACOs is the quality and costs assessments do not include the cost of Medicare Part D drugs; these are not included in the total cost of care. This means that prescribers in these ACOs can simply prescribe the best treatments purely from a clinical standpoint. Commercial ACOs, like those offered by Aetna and Cigna, pro-vide bonus and shared savings programs using diabetes-related measures as well.11

Also, the new Medicare Access and Children’s Health Insur-ance Program Reauthorization Act’s Quality Payment Program scheduled to begin on January 1, 2017, is a significant piece of legislation providing significant bonuses and penalties for Medi-care physicians. The program mandates penalties and payments associated with most health care specialty areas. For diabetes, physicians are measured on several of the standard diabetes mea-sures (eg, HbA1c, eye exam, foot exam) in addition to practice improvement activities such as on-site diabetes educators, pa-tient self-management training, and group visits with patients with diabetes.12,13

It is important to note that CMS-managed programs may experience significant changes as the new US Presidential ad-ministration takes control in 2017.

Table 1. Glycemic Targets for Older Adults With Diabetes

GuidelinesFasting Plasma Glucose (mg/dL)

Random Blood Glucose (mg/dL) HbA1c (%)

AMDA – Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Society 140 < 8.0

American Geriatric Society < 7.5a

American Diabetes Association (2016) ≥ 126 (7.0 mmol/L) < 8.5

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/ American Diabetes Association (2009)

< 140 < 180

Abbreviation: HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c.aGoals based on life expectancy, frailty, presence of comorbidities, cognitive impairment, and functional disability.

jcp1216_Diabetes_Stefanacci.indd 8 12/5/16 5:11 PM

special article

www.jcponline.com December 2016 • Journal of Clinical Pathways S9

treating diabetes in assisted livingOlder adults come to assisted living (AL) facilities for assistance, and an increasing number are coming specifically for diabetes management help. More than 25% of Americans aged 65 years and older have type 2 diabetes, and another 50% have a condi-tion known as prediabetes (blood glucose levels that are higher than normal but not yet high enough to be diagnosed as dia-betes). The number of AL residents with diabetes is significant and growing. By 2050, as many as 30% of adults in the United States could have diabetes if current trends hold, compared with 10% currently, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC estimates are based on increased odds of developing type 2 diabetes with age, increasing obe-sity, population growth of high risk minority groups, and people with diabetes living longer.14

In addition to the increased numbers of older diabetic pa-tients, their care needs are significant as well. Older people with diabetes have higher rates of amputation, heart attack, vi-sual impairment, and kidney disease. They seek emergency care for blood-sugar crises at twice the rate of the general diabetes population. These consequences of poor management are often immediate and costly, often forcing transfer out of the home into the AL community. This can occur from either blood sugars being too low or too high. In the case of hyperglycemia there are several symptoms which could force an AL resident with diabetes outside of their home in the AL to a nursing home because of worsening of their health requiring increased care needs. These issues from hyperglycemia could include blurred vision, new or increased confusion, lethargy, weight loss and/or worsening incontinence.14

Conversely, the relationship between hypoglycemic events and dementia may be bidirectional, as shown in a recent study of older adults with diabetes mellitus (DM).14 Hypoglycemia com-monly occurs in patients with DM and may negatively influ-ence cognitive performance; in turn, cognitive impairment can compromise DM management and lead to hypoglycemia.15 This is consistent with a growing body of evidence that DM may

increase the risk for developing cognitive impairment, including Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia, and there is research interest in whether DM treatment can prevent cognitive decline. When blood glucose declines to low levels, cognitive function is impaired and severe hypoglycemia may cause neuronal damage. Research on the potential association between hypoglycemia and cognitive impairment has produced conflicting results.15

conclusionThe pervasive nature of diabetes demands monitoring and man-agement and control from several stakeholder perspectives in order to improve quality care and reduce costs. Practice guide-lines that include patient education, system-wide monitoring, and provider incentives and penalties are a few of the controls our health care system provides to achieve better care. As prac-tice guidelines evolve to be more effective within the changing health care environment, so too will the management of this disease.

References1. Clark NG. A word about quality of care in diabetes. National Committee of Quality

Assurance website. http://www.ncqa.org/PublicationsProducts/OtherProducts/Quali-tyProfiles/FocusonDiabetes/AWordAboutQualityofCareinDiabetes.aspx. Accessed November 6, 2016.

2. Ali MK, McKeever Bullard K, Saaddine JB, Cowie CC, Imperatore G, Gregg EW. Achieve-ment of goals in U.S. diabetes care, 1999–2010. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1613-1624.

3. National Committee of Quality Assurance. Addressing the quality gaps in diabetes prevention and care. http://www.ncqa.org/PublicationsProducts/OtherProducts/Quali-tyProfiles/FocusonDiabetes/AddressingtheQualityGaps.aspx. Accessed November 6, 2016.

4. American Geriatrics Society. Five things physicians and patients should question. The American Geriatrics Society. http://www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/Five_Things_Physicians_and_Patients_Should_Question.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2016.

5. American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: liberaliza-tion of the diet prescription improves quality of life for older adults in long-term care. J Am Diet Assoc. December 2005;105(12):1955-1965. www.andjrnl.org/article/S0002-8223(05)01742-6/pdf. Accessed November 8, 2016.

6. Courtemanche T, Mansueto G, Hodach R, Handmaker K. Population health approach for diabetic patients with poor A1C control. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):465-472.

7. Choe HM, Mitrovich S, Dubay D, Hayward RA, Krein SL, Vijan S. Proactive case man-agement of high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus by a clinical pharmacist: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(14):253-260.

8. Study: UnitedHealthcare’s diabetes health plan can lead to improved health, more effective disease management, better cost control [press release]. Minneapolis, MN: UnitedHealth Group; January 10, 2013. http://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/news-room/ articles/news/unitedhealthcare/2013/0110uhcstudydiabetes.aspx. Accessed March 3, 2016.

9. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Part C and D performance data. cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/Performance-Data.html. Accessed November, 7, 2016.

10. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Accountable Care Organization 2016 pro-gram quality measure narrative specifications. January 13, 2016.

11. Lewis VA, Colla CH, Schpero WL, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. ACO contracting with private and public payers: a baseline comparative analysis. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(12):1008-1014.

12. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/Final-MDP.pdf. Accessed August 3, 2016.

13. Administration takes first step to implement legislation modernizing how Medicare pays physicians for quality [news release]. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; April 27, 2016. http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2016/04/27/administration-takes-first-step-implement-legislation-modernizing-how-medicare-pays-physicians.html. Access August 9, 2016.

14. Stefanacci RG, Haimowitz D. Assisting for better diabetes management. Geriatr Nurs. 2013;34(5):418-420.

15. Yaffe K, Falvey CM, Hamilton N, et al. Association between hypoglycemia and demen-tia in a biracial cohort of older adults with diabetes mellitus. JAMA Intern Med. 2013; 173(14):1300-1306.

Given the long timeframe to achieve theorized

microvascular benefits of tight control, glycemic

targets should reflect patient goals, health status, and life

expectancy.

jcp1216_Diabetes_Stefanacci.indd 9 12/5/16 5:11 PM

special article

S10 Journal of Clinical Pathways • December 2016 www.jcponline.com

Despite the high incidence of diabetes, disease man-agement remains elusive and the per patient costs have continued to escalate—all factors that have targeted diabetes as an open field for new drug development and new management strategies. But new approaches do not necessarily improve the quality of care if they are not effectively implemented. What needs to hap-pen to see real advances in diabetes care?

The incidence of diabetes in the United States has more than doubled over the past 35 years, according to Cen-

ters for Disease Control and Prevention estimates.1 During that same period, diabetes control remained elusive due to the progressive nature of the disease and the substantial con-tribution of lifestyle issues—primarily a diet high in sugars and carbohydrates, and lack of exercise.

All of this results in a growing population failing to achieve and maintain glucose control, putting them at risk for many complications ranging from kidney disease, neu-ropathies and blindness to heart attacks and strokes.

So it is no surprise that diabetes has become one of the major targets for new therapies. The number of new diabetes

The Solution to More Effective Diabetes Management: Better Products or Better Programs?Larry Blandford, PharmD

affiliations: Precision For Value, Boston, MA

disclosures: Dr Blandford is executive vice president and managing partner of Integrated Market Access for Precision for Value.

Table 1. FDA-Approved Insulin and Diabetes Drugs, 2013-20162,a

Brand Name Generic Name Approval Date

Soliqua insulin glargine and lixisenatide November 21, 2016

Xultophy insulin degludec and liraglutide November 21, 2016

Invokana canagliflozin March 29, 2016

Nesina alogliptin January 25, 2016

Basaglar insulin glargine injection December 16, 2015

Tresiba insulin degludec injection September 25, 2015

Ryzodeg insulin degludec and insulin aspart injection September 25, 2015

Toujeo insulin glargine injection February 25, 2015

Glyxambi empagliflozin and linagliptin January, 2015

Trulicity dulaglutide September 18, 2014

Invokamet canagliflozin and metformin HCl August 8, 2014

Jardiance empagliflozin August 1, 2014

Afrezza insulin human inhalation powder June 27, 2014

Tanzeum abliglutide May 2014

Farxiga dapagliflozin January 2014

Duetact pioglitazone HCl and glimepiride January 2013

aAdapted from FDA.gov. Table includes all drugs approved for the treatment of diabetes.Abbreviation: HCl, hydrochloride.

jcp1216_Diabetes_Blandford.indd 10 12/6/16 12:45 PM

special article

www.jcponline.com December 2016 • Journal of Clinical Pathways S11

products to come to market over the past 15 years has ex-ploded—21 drugs approved between 2000 and 2012 com-pared with 10 over the previous decade (1999-2000), with 16 more approved between 2013 and 2016 (Tables 1 and 2).2

the high costs of treatmentThe costs of diabetes treatments are extremely high from a care standpoint, as diabetes is part of a compendium of met-abolic disorders that lead to generally poor health and the increasing need for interventions. Estimates from various sources have indicated that the average diabetes patient spends between $1000 and $6000 per year for medications, test ma-terials, and needles.3-5 Due to the high incidence of comorbid conditions in these patients (an average of 2.6 per patient), they spend another $1.05 on other medications and $0.70 on nondiabetes equipment for every $1 spent on diabetes medi-cations.4 Insurers and employers also experience these high costs with diabetes medications ranked as the costliest non-

specialty medication class for 5 years running, according to one source.6

Additionally, a number of new and evolving nonmedi-cation care interventions for improving care have demon-strated improvements in diabetes care. From monitoring technology (pumps/pods) to medical homes7 to community programs8 to mobile apps,9 care interventions present new opportunities to achieve better outcomes. Each of these brings varying levels of direct and indirect costs into the health care system.

Yet, given the extensive amount of money spent on and resources provided for diabetes management, the question becomes: are better products or better programs the solu-tion to more effective diabetes care?

getting to better diabetes careThe pathophysiology of diabetes suggests that comparison of cost per hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) reduction for products

Table 2. FDA-Approved Insulin and Diabetes Drugs, 2000-20122,a

Brand Name Generic Name Approval Date

Janumet XR sitagliptin and metformin HCl extended-release February 2012

Jentadueto linagliptin plus metformin HCl February 2012

Bydureon exenatide extended-release January 2012

Juvisync sitagliptin and simvastatin October 2011

Tradjenta linagliptin May 2011

Kombiglyze XR saxagliptin/metformin HCl extended-release November 2010

Victoza liraglutide January 2010

Onglyza saxagliptin July 2009

PrandiMet repaglinide/metformin HCl June 2008

Janumet sitagliptin/metformin HCl March 2007

Januvia sitagliptin October 2006

ACTOplus met pioglitazone HCl and metformin HCl August 2005

Levemir insulin detemir June 2005

Byetta exenatide April 2005

Symlin pramlintide March 2005

Apidra insulin glulisine February 2004

Metaglip glipizide/metformin HCl October 2002

Avandamet rosiglitazone maleate and metformin HCl October 2002

Lantus insulin glargine April 2000

NovoLog Insulin aspart November 2001

NovoLog 70/30 70% insulin aspart protamine and 30% insulin aspart November 2001

aAdapted from FDA.gov. Table includes all drugs approved for the treatment of diabetes.Abbreviation: HCl, hydrochloride.

jcp1216_Diabetes_Blandford.indd 11 12/6/16 12:45 PM

special article

S12 Journal of Clinical Pathways • December 2016 www.jcponline.com

and care programs is too simplistic a target and that simply adding to a patient’s treatment plan may not achieve the best results. Products perform better for patients when the care guides dosing titration to maximize glucose control while minimizing side effects—and programs perform bet-ter when the medication selection and use are optimized. Management approaches in diabetes still need to integrate the products available into individualized treatment plans that are supported by effective care programs, if they are to succeed.

Most often, the best combination of products and care programs results from combined patient/clinician/payer decisions that can vary according to local health system dy-namics (integration of primary and specialty care); popula-tion characteristics (ethnicity and access to services); and organizational structures (profit status and service area). Each entity must enhance its assessment of the value of

medications and care initiatives based on these variables in order to achieve further advances in the management of diabetes at the levels of both the individual patient and the entire diabetes community.

Reaching the goal of effective diabetes management for all patients will require significant research to identify which combinations of products and programs are most likely to benefit individual patients. Multiple stakeholders must con-tribute to this research, including providers, payers, pharma-ceutical companies, care management programs, technology solutions, and, certainly, patients. The level of engagement and cooperation will determine the ultimate outcome of achieving more effective diabetes management.

References1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Crude and age-adjusted incidence of

diagnosed diabetes per 1,000 population aged 18-79 years, United States, 1980-2014. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/incidence/fig2.htm. Accessed No-vember 9, 2016.

2. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA-approved diabetes medicines. http://www.fda.gov/ForPatients/Illness/Diabetes/ucm408682.htm. Accessed November 9, 2016.

3. Consumer Reports. Get help with the high cost of managing diabetes. http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/2013/01/get-help-with-the-high-cost-of-managing-diabe-tes/index.htm. Accessed November 9, 2016.

4. American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes care in the US in 2007. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(3):596-615.

5. Raloff J. The high cost of diabetes. Sci News. August 16, 2010. https://www.scien cenews.org/blog/science-public/high-cost-diabetes. Accessed November 9, 2016.

6. Express Scripts. Diabetes: 5 Rx trends to explore ahead of ADA ’16. https://lab.express-scripts.com/lab/insights/industry-updates/diabetes-five-rx-trends-to-ex-plore-ahead-of-ada-16. Published June 7, 2016. Accessed November 9, 2016.

7. Bojadzievski T, Gabbay RA. Patient-centered medical home and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(4):1047-1053.

8. Cranor CW, Bunting BA, Christensen DB. The Asheville Project: long-term clinical and economic outcomes of a community pharmacy diabetes care program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43(2):173-184.

9. Quinn CC, Sareh PL, Shardell ML. Mobile diabetes intervention for glycemic control: impact on physician prescribing. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2014;8:362-370.

Estimates from various sources have indicated that the average

diabetes patient spends between $1000 and $6000

per year for medications, test materials, and needles.

jcp1216_Diabetes_Blandford.indd 12 12/6/16 12:45 PM

Health care is now more connected than ever.

Why should your news be any different?

Managed Health Care Connect provides a single platform for access

to the latest information from Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care

and Aging, Pharmacy Learning Network, and First Report Managed

Care. It’s your digital home for managed care news.

See what’s in it for you.managedhealthcareconnect.com

Managed

PHARMACY LEARNING NETWORKpln

MHCC_Ad.indd 2 7/26/16 11:14 AM

We invite you to visit www.intarcia.com to learn more.

Across chronic diseases, medication non-adherence can compromise clinical outcomes and drive excess cost to the healthcare system. Intarcia is working to address this problem through innovative technologies.

TIME DISRUPTTM

2

© 2016 Intarcia Therapeutics, Inc. All rights reserved. 10/16

Intarcia_Time2Disrupt_1216.indd 1 11/8/16 9:37 AM