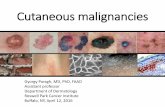

Appearance of cutaneous malignancies of the head and neck

Transcript of Appearance of cutaneous malignancies of the head and neck

m

Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology (2013) 24, 2-8

Appearance of cutaneous malignancies of the headand neck

Genevieve Andrews, MD, Bryan Anderson, MD, Rogerio Neves, MD

From the Division of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, Penn State Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, Pennsylvania

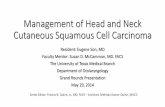

The spectrum of cutaneous malignancies of the head and neck ranges from tumors that are fairly wellbehaved, such as the majority of basal cell carcinomas, to very aggressive cancers with a high metastaticrate, such as Merkel cell carcinoma. Most forms of cutaneous malignancy have characteristic clinicalpresentations, which assist in their clinical diagnosis. The goal of this article is to review theappearances and clinical presentations of common nonmelanoma skin cancers (basal and squamous cellcarcinomas), uncommon nonmelanoma skin cancers (Merkel cell carcinoma and dermatofibrosarcomaprotuberans), and the various subtypes of cutaneous melanoma.© 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

KEYWORDS:Skin cancer appearance;Melanoma presentation

vadshddhosm

mpi

The majority of cutaneous malignancies affect sun-ex-posed areas of the body; therefore, head and neck surgeonswill commonly encounter patients with skin malignancies.The goal of this article is to review the appearances andclinical presentations of common nonmelanoma skin can-cers (basal and squamous cell carcinoma [SCC]), uncom-mon nonmelanoma skin cancers (Merkel cell carcinoma[MCC] and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans [DFSP]), andthe various types of cutaneous melanoma. For each cancer,the clinical appearance, demographics, etiologic and riskfactors, common body locations, and risk of regional lymphnode involvement will be discussed.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which is the most commonform of skin cancer, is thought to arise from the basalkeratinocytes in the epidermis and around adnexal struc-tures. It occurs in men more often than women and usuallyoccurs in those older than 40 years. Ultraviolet radiation,especially prolonged sun exposure, induces mutations intumor suppressor genes, which leads to uncontrolled prolif-eration of basal cells.1,2 Fair-skinned individuals are much

ore likely to develop BCCs than are darker-skinned indi-

Address reprint requests and correspondence: Genevieve Andrews,MD, Division of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, Penn StateHershey Melanoma Center, Head & Neck Oncologic Surgery, Penn StateHershey Medical Center, 500 University Drive, Mail Code H091, Hershey,PA 17033-0850

E-mail address: [email protected].

1043-1810/$ -see front matter © 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.otot.2012.12.002

iduals. Patients with a history of radiotherapy to the headnd neck, as well as arsenic ingestion, are also at risk forevelopment of multiple BCCs. Although most BCCs areporadic, presentation with multiple BCCs might suggest aereditary disease. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid BCC syn-rome), Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome, Rombo syn-rome, Oley syndrome, and xeroderma pigmentosum areereditary tumor syndromes associated with the formationf multiple BCCs.3 There have also been reports of non-yndromic hereditary disease in patients presenting withultiple BCCs in the absence of other syndromic features.4

More than 90% of BCCs occur on the face. BCC rarelyspreads to lymph nodes, and very rarely metastasizes dis-tantly.2 There are several types of BCC including nodular,

icronodular, infiltrative, pigmented, morpheaform, and su-erficial BCC, with the micronodular, morpheaform, andnfiltrative types being the more aggressive.5

Nodular BCC is the most common type of BCC, andappears as a pearly white or pink dome-shaped papule(Figure 1), with or without ulceration. Telangiectatic vesselson the surface of the lesion become obvious as the lesionenlarges, and the center frequently ulcerates and bleeds.These tumors often have associated blood-tinged crust.Nodular BCCs usually first extend peripherally, and thenafter a time will penetrate deeply into the subcutaneoustissues. However, as with all tumors, the growth pattern can

be irregular.1,2

amd

3Andrews et al Cutaneous Malignancies of the Head and Neck

The morpheaform, or sclerosing, type of BCC is a tumorthat has innocuous surface characteristics (Figure 2). Thelesion is firm. However, it is waxy, flat or slightly raised,white or yellow, borders are indistinct and blend with nor-mal skin, and can have broad extension beyond the apparentborders. These tumors can mimic the appearance of a scar.Follicular dropout, loss of hair follicle structures, within thearea affected is one clue to the diagnosis. The averagesubclinical extension beyond the apparent borders of mor-pheaform BCC in one study was 7.2 mm.6 Owing to thedifficulty distinguishing this lesion from normal surround-

Figure 1 Nodular basal cell carcinoma. These lesions appear aspearly white or pink dome-shaped papules with telangiectaticvessels on the surface.

Figure 2 Morpheaform basal cell carcinoma. This lesion iswaxy, flat or slightly raised, or white or yellow, and has indistinct

borders that blend with normal skin surrounding the lesion.ing tissue, Mohs surgery is critical for excision of thesetumors with negative margins.1,2

Micronodular and infiltrative BCC (not shown here), incombination with the morpheaform subtype, make up agroup of high-risk histologic subtypes of BCC.5 They have

higher metastatic and recurrence rate, and they invadeore widely, deeply, and rapidly, with a lower rate of early

etection compared with the other subtypes.7 In general,Mohs surgery should be used for these subtypes to ensurethat negative margins are achieved given the frequent in-nocuous appearance clinically.

Pigmented BCC is a BCC that contains melanin thatimparts blue, brown, or black color to the lesion (Figure 3).Pigmented basal cells can mimic the appearance of mela-noma, and in some cases, one cannot clinically distinguishthe two with 100% certainty. The tumor most often still hasthe pearly translucent border more characteristic of BCC,which is a helpful distinguishing factor. The histologicpattern most associated with pigmented BCC is the nodularpattern. The superficial type of BCC is the least locallyaggressive of the BCC subtypes because it spreads periph-erally first, and invades the subcutaneous tissue late. Itappears as a well-circumscribed, round-to-oval, red, scalingpatch that can resemble eczema, tinea, or psoriasis. However,careful inspection of edges of the lesion can reveal the thin,raised, pearly white border characteristic of BCC (Figure 4). Itmost commonly occurs on the trunk or extremities but mayoccur on the face.1,2

Cutaneous SCC (cSCC) is a malignancy of keratinocytesthat arises from the epidermis of the skin. It occurs in menmore than women, and usually in those older than 55 years.Ultraviolet radiation exposure is the most frequent etiologicfactor for the development of cSCC. However, human pap-

Figure 3 Pigmented basal cell carcinoma. This lesion can be anyof the subtypes of basal cell carcinomas with the added characteristicthat the tumor contains melanin that imparts a blue, brown, or blackcolor to the lesion.

illomavirus infection, immunosuppression, chronic inflam-

ms0

mi

ae

suc

4 Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology, Vol 24, No 1, March 2013

mation, industrial carcinogens, and arsenic ingestion arealso associated risk factors. SCCs are commonly located onsun-exposed areas of the body.1,2 These skin cancers are

ore likely than BCCs to regionally and distantly metasta-ize, with reported overall rate of metastasis ranging from.1% to 9.9%.8 SCCs of the skin can be divided into well-

differentiated or poorly differentiated types, with the poorlydifferentiated tumors exhibiting a more aggressive biology.

Differentiated SCC often feels hard and hyperkeratotic,and appears as an indurated papule, plaque, or nodule withelevated margins (Figure 5). This lesion may ulcerate andaccumulate crust in its center, and a keratotic horn mayappear to extend from the margin or center of the lesion.1,2

Poorly or undifferentiated cSCC is usually soft, fleshy, orpapillomatous with no to minimal hyperkeratosis (Figure 6).

Figure 4 Superficial basal cell carcinoma. This lesion appears aswell-circumscribed, round-to-oval, red, scaling plaque, with the

dges of the lesion exhibiting a thin, raised, pearly white border.

Figure 5 Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. This le-ion appears as a hyperkeratotic indurated papule, plaque, or nod-le with elevated margins, which often ulcerates and accumulates

rusts in its center.It often ulcerates, and can bleed easily.1,2 The rate of localrecurrence and metastases of poorly differentiated SCCs isdouble to triple the rates of well-differentiated tumors.9

Keratoacanthoma is a variant of SCC that presents as adome-shaped nodule with a central keratotic plug. Theyoften present as a firm, round, primarily skin-colored nodulewith slight red or brown hues. Keratoacanthomas usuallyoccur in patients older than 50 years. The main risk factorsassociated with this disease is ultraviolet radiation exposure.As a result, this lesion has a predilection for sun-exposedsites of the body. Human papillomavirus infection andchemical carcinogens are also thought to be associated withthis lesion. Keratoacanthoma exhibits rapid growth and cancause cosmetic disfigurement. There are clinical variants ofkeratoacanthomas, including multiple synchronic tumors,and a giant variant termed keratoacantoma cetifugum mar-ginatum. However, most spontaneously regress in 2-6months or sometimes after 1 year. Rarely, keratoacantho-mas metastasize to lymph nodes and viscera.1,2

Melanoma is a malignancy of melanocytes, the pigment-producing cells, that mainly occurs in the skin; however, itcan also arise in mucous membranes, retina, and leptome-ninges. The reported incidence of melanoma has been in-creasing over the past 50 years.1 The Surveillance Epide-

iology and End Results data on melanoma reveal anncidence of 21 per 100,000 persons.10 Importantly, mela-

noma is the most deadly skin cancer, as it is responsible for75% of the skin cancer deaths in the United States.1 Thereare four major subtypes of melanoma, including superficialspreading, nodular, acral lentiginous, and lentigo maligna mel-anoma (LMM), which are discussed herein. The rate of re-

Figure 6 Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Thislesion appears as a soft, fleshy, friable, papillomatous mass with nohyperkeratosis.

gional lymph node metastasis ranges from 2% to 40% depend-

oeaco

5Andrews et al Cutaneous Malignancies of the Head and Neck

ing on the depth of invasion of the melanoma.11-13

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM), which is also discussed later inthe text, is an uncommon type of melanoma, which deservesspecific mention owing to the unique behavior of this entitycompared with all other types of cutaneous melanoma.1

Superficial spreading melanoma (SSM) is the most com-mon type of melanoma that usually presents as a change ina previously existing pigmented lesion such as a dysplasticnevus. Patients will often describe a gradually darkenedmole, or change in shape and variation in coloration, orelevation in one of their nevi (Figure 7). SSM displays colormixtures of brown, black, red, and white, with blue and graybeing more specific for SSM.1,2 The usual age of onset forSSM is 30-50 years. SSM is more common in women, and70% occur in Caucasians. Typically, there are no symptomsassociated with these tumors, but on occasion, patients willcomplain of new-onset itching at the site. Risk factors forthe development of SSM include the presence of precursorlesions, such as dysplastic nevi or large congenitalnevomelanocytic nevi, a history of melanoma in first-degreerelatives, fair skin color, and severe childhood sunburns.This tumor usually occurs as an isolated solitary lesion ofthe anterior trunk, back, and legs. This is the most commontype of melanoma, representing 70% of all melanomas.2

Nodular melanoma is the second most common type ofmelanoma that presents as a thick plaque or an exophytic,dome-shaped, or “blueberry-like” nodule (Figure 8). It mayulcerate or exhibit a smooth or crusted surface, and usuallyhas sharply defined borders.1,2 Nodular melanoma usuallyccurs in middle life (40-50 years of age), and occursqually in men and women. This melanoma type representslarger percentage of all melanomas in Japanese people

ompared with other races. In the United States, 15%-30%f all melanomas are the nodular type.2

LMM is a type of melanoma that always starts as alentigo maligna (LM), a macular intraepidermal neoplasm,

Figure 7 Superficial spreading melanoma. This lesion usuallypresents as a change in a previously existing pigmented lesion, suchas from a dysplastic nevus. It displays color mixtures of brown, black,

red, white, blue, and gray.which by definition is a melanoma in situ. Focal papular andnodular areas within an LM signal a switch from radial tovertical growth, and thus invasion into the dermis, convert-ing the LM to LMM (Figure 9).1,2 The median age ofdevelopment of LMM is 65 years and occurs equally in menand women. Chronic ultraviolet radiation exposure is the riskfactor for LMM. This lesion occurs on sun-exposed areas such

Figure 8 Nodular melanoma. This lesion appears as a thickplaque or an exophytic, dome-shaped, or “blueberry-like” nodulethat is well circumscribed.

Figure 9 Lentigo maligna melanoma. This lesion presents as achange in a previously existing lentigo maligna lesion, with thechange being most commonly new focal papular and nodular

areas.

mts

m

6 Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology, Vol 24, No 1, March 2013

as the face, neck, dorsa of the forearms, and hands. Patientswith LMM have associated solar damage to surrounding skin.LMM represents 4%-15% of all melanomas.1,2

Acral lentiginous melanoma is a type of melanoma thatdevelops on the hands or feet, with a specific subtype,subungual melanoma, occurring under fingernails or toe-nails. This type of melanoma makes up 7%-9% of all mel-anomas. By definition, this type of melanoma does notoccur on the head and neck. Thus, acral lentiginous mela-noma will not be discussed in detail here.1,2

Amelanotic melanoma is a descriptive term for a melanomathat does not have the characteristic dark pigment marker(Figure 10). All types of melanoma can be amelanotic, al-though it occurs more commonly in the desmoplastic andsubungual acral lentiginous types, with 1.8%-8.1% of all mel-anomas being amelanotic (Figure 10).14 Owing to the lack ofpigmentation of these tumors, clinical diagnosis of amelanoticmelanoma often occurs at a later stage than melanomas withthe typical dark pigmentation. It is also seen as the primaryform of melanoma in patients with albinism.

DM is a rare type of melanoma that presents as irregularsclerotic plaques with little or no pigmentation (Figure 11).DM makes up 1%-4% of all melanomas. Histopathologi-cally, DM displays extensive dermal fibrosis, with two de-scribed histologic subtypes, pure and mixed. Pure DM isusually defined as melanoma in which �90% of the inva-sive component of the tumor is desmoplastic, characterizedby low cellularity and a fibrotic appearance histologically.Mixed DM also has desmoplasia, but it is not as prominentand contains a variable component of solid spindle cellmelanoma.15 DM more commonly occurs in men, with a

ean age at diagnosis of 60 years.16 Ultraviolet radiation ishe primary risk factor for the development of DM, and asuch, it usually occurs on sun-exposed areas of the body.2

Although DM is diagnosed at higher Breslow thickness andClark level compared with other types of melanoma, lymph

Figure 10 Amelanotic melanoma. This lesion can be any type ofmelanoma that does not have the characteristic dark pigment

marker.node and organ metastases are rare, and prognosis is morefavorable compared with other Breslow depth–matchedforms of melanoma.15 The reported rates of lymph node

etastasis are 1% for pure DM and 18% for mixed DM.17,18

The lower incidence of lymph node metastases is intuitivegiven the sarcoma-like nature of this type of melanoma. Ofnote, local recurrence rates for DM are higher than for othertypes of melanoma, with reports documenting rates rangingfrom 14% to 56%, thus justifying resecting these tumorswith generous margins when possible.15,16,19

MCC is a rare cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor thatpresents as a cutaneous to subcutaneous papule or dome-shaped nodule (usually 0.5-5 cm) that is pink, red to violet,or reddish brown (Figure 12). MCC usually occurs as asolitary lesion that grows rapidly and may ulcerate when

Figure 11 Desmoplastic melanoma. This lesion presents as anirregular sclerotic plaque with little or no pigmentation.

Figure 12 Merkel cell carcinoma. This lesion appears as acutaneous to subcutaneous papule or dome-shaped nodule that is

pink, red to violet, or reddish brown.

ydsaain

pticDb

toir

dwcsgtmigp

tddd

7Andrews et al Cutaneous Malignancies of the Head and Neck

large.1,2 MCC usually occurs in Caucasians older than 50ears, with a slight male predominance.20 Risk factors forevelopment of MCC include ultraviolet radiation expo-ure, Merkel cell polyomavirus infection, advancing age,nd immunosuppression. It most often occurs on the headnd extremities as solitary or multiple lesions. MCC exhib-ts a remarkably high rate of spread to regional lymphodes, with a 32% rate of occult nodal disease.21

DFSP is a rare, slow-growing, locally aggressive tumorthat is initially clinically indolent because it appears like ascar (Figure 13). This lesion presents as a firm induratedplaque that can develop exophytic nodules. They are typi-cally skin-colored to red or brown.2 DFSP usually occurs inatients aged 30-50 years, with equal distribution except inhe greater-than-70-year-old group, in which DFSP predom-nates in men. Contrary to all other types of skin malignan-ies, DFSP is more common in darker-skinned individuals.evelopment of DFSP or the acceleration of its growth haseen associated with trauma, as well as pregnancy.22-24 It

has been found that 90% of DFSPs have chromosomalrearrangements that lead to excess platelet-derived growthfactor beta expression. Targeting the platelet-derivedgrowth factor receptor in DFSP with imatinib, a selectivetyrosine kinase inhibitor, has been approved by the Foodand Drug Administration for use in unresectable, recurrent,or metastatic DFSPs.25 Although predominantly located onhe trunk (42%) and extremities (34%), DFSPs may alsoccur on the head and neck (15%), and in these locations, its associated with a greater risk of morbidity and localecurrence.4,26-28

As demonstrated by the myriad of tumors and theirclinical presentations described earlier in the text, the spec-trum of cutaneous malignancies of the head and neck rangesfrom tumors that are fairly well behaved, such as the ma-jority of BCCs, to very aggressive cancers with a highmetastatic rate, such as MCC. Each type of cutaneous ma-lignancy has characteristic presentations, which can help inthe clinical diagnosis of these lesions. However, there areseveral skin malignancies, such as amelanotic melanoma,

Figure 13 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. This tumorlooks like a scar, presenting as a firm indurated plaque withexophytic nodules that is skin-colored to red or brown.

DM, and DFSP, that present late and are difficult to clini-

cally diagnose owing to their lack of pigmentation or subtlesubcutaneous spread. Thus, head and neck surgeons, whocommonly encounter cutaneous malignancies, need to befamiliar with the various presentations of skin cancers sothat these lesions can be identified, and subsequently patho-logically evaluated and treated in an appropriate manner.For instance, for lesions that appear concerning for mela-noma on clinical presentation, appropriate biopsy with anexcisional or incisional full-thickness biopsy technique isimportant in obtaining the correct pathologic diagnosis todirect further evaluation and stage the patient. Shave biop-sies, although often adequate for BCCs and cSCCs, areoften inadequate for the biopsy of lesions suspicious formelanoma. Apart from using the gross appearance of theselesions, patient demographics, risk factors, and the presenceor absence of regional or distant disease to clue one into thediagnosis, dermatoscopy can be used to further characterizethe microscopic appearance of the lesion before biopsy.Dermatoscopy is the use of a nonpolarized or polarized lightmicroscope that allows visualization of skin structures fromthe epidermis to the superficial papillary dermis that are notvisible to the naked eye.29 Dermatoscopes can capture aigital image of the magnified appearance of the lesion,hich can be used to help decide which lesions are suspi-

ious for malignancy and which need biopsy.30 Dermato-copy has been shown to improve the accuracy of dermatolo-ists in diagnosing nonmelanoma skin cancers, melanoma, andhe elusive amelanotic melanoma.31-33 Disadvantages of der-

atoscopy are the significant amount of training needed in thenterpretation of the dermatoscopic images. Most dermatolo-ists have had training in this technique and use it in theirractice.34 However, dermatoscopy is not part of the typical

residency or fellowship training for otolaryngology—headand neck surgeons. One prospective study showed thatprimary care physicians trained in dermatoscopy signifi-cantly improved their accuracy of legitimate referrals to adermatologist for a suspected skin cancer, thus suggestingthat nondermatologists can effectively learn this tech-nique.35 Perhaps with the projected continued increase inhe incidence of cutaneous malignancies, there will be aemand in the future for head and neck surgeons to useermatoscopy in addition to history and examination toecide which skin lesions require biopsy.

References

1. Habif TP: Clinical Dermatology. (ed 4). Philadelphia, PA, Mosby,2004

2. Wolff K, Johnson RA. FitzPatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis ofClinical Dermatology (ed 6). New York, NY, McGraw-Hill, 2009

3. Parren LJ, Frank J: Hereditary tumour syndromes featuring basal cellcarcinomas. Br J Dermatol 165:30-34, 2011

4. Happle R: Nonsyndromic type of hereditary multiple basal cell carci-noma. Am J Med Genet 95:161-163, 2000

5. Hendrix JD, Jr, Parlette HL: Micronodular basal cell carcinoma: adeceptive histiologic subtype with frequently clinically undetected

tumor extension. Arch Dermatol 132:295-298, 1996

8 Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology, Vol 24, No 1, March 2013

6. Salasche SJ, Amonette RA: Morpheaform basal cell epitheliomas: astudy of subclinical extensions in a series of 51 cases. J Dermatol SurgOncol 7:387-394, 1981

7. Lang PG, Maize JC: Basal cell carcinoma, in Freidman RJ, et al (eds):Cancer of the Skin (ed 1). Philadelphia, PA, W. B. Saunders Co., 1991,pp 51-53

8. Weinberg AS, Ogle CA, Shim EK: Metastatic cutaneous squamouscell carcinoma: an update. Dermatol Surg 33:885-899, 2007

9. Dinehart SM, Pollack SV: Metastases from squamous cell carcinomaof skin and lip: an analysis of 27 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 21:241-248, 1989

10. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al (eds): SEER CancerStatistics Review, 1975-2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations). Bethesda,MD, National Cancer Institute. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/, based on November 2011 SEER data submis-sion, posted to the SEER web site, April 2012

11. Thompson JF, Shaw HM: Sentinel node mapping for melanoma:results of trials and current applications. Surg Oncol Clin N Am16:35-54, 2007

12. Ferrone CR, Panageas KS, Busam K, et al: Multivariate prognosticmodel for patients with thick cutaneous melanoma: importance ofsentinel lymph node status. Ann Surg Oncol 9:637-645, 2002

13. Gershenwald JE, Mansfield PF, Lee JE, et al: Role for lymphaticmapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thick (� or� 4 mm) primary melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol 7:160-165, 2000

14. Koch SE, Lange JR: Amelanotic melanoma: the great masquerader.J Am Acad Dermatol 42:731-734, 2000

15. Mohebati A, Ganly I, Busam KJ, et al: The role of sentinel lymph nodebiopsy in the management of head and neck desmoplastic melanoma.Ann Surg Oncol (in press)

16. Quinn MJ, Crotty KA, Thompson JF, et al: Desmoplastic and desmo-plastic neurotropic melanoma: experience with 280 patients. Cancer83:1128-1135, 1998

17. Pawlik TM, Ross MI, Prieto VG, et al: Assessment of the role ofsentinel lymph node biopsy for primary cutaneous desmoplastic mel-anoma. Cancer 106:900-906, 2006

18. Hawkins WG, Busam KJ, Ben-Porat L, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma:a pathologically and clinically distinct form of cutaneous melanoma.Ann Surg Oncol 12:207-213, 2005

19. Anstey A, McKee P, Jones EW: Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: aclinicopathological study of 25 cases. Br J Dermatol 129:359-371,1993

20. American Joint Committee on Cancer: AJCC Staging Manual (ed 7).

New York, NY, Springer, 201021. Gupta SG, Wang LC, Penas PF, et al: Sentinel lymph node biopsy forevaluation and treatment of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma:Farber, Dana experience and meta-analysis of the literature. ArchDermatol 142:685-690, 2006

22. Elgart GW, Hanly A, Busso M, et al: Bednar tumor (pigmenteddermatofibrosarcoma protuberans) occurring in a site of prior immu-nization: immunochemical findings and therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol40:315-317, 1999

23. Parlette LE, Smith CK, Germain LM, et al: Accelerated growth ofdermatofibrosarcoma protuberans during pregnancy. J Am Acad Der-matol 41:778-783, 1999

24. Har-Shai Y, Govrin-Yehudain J, Ullmann Y, et al: Dermatofibrosar-coma protuberans appearing during pregnancy. Ann Plast Surg 31:91-93, 1993

25. Johnson-Jahangir H, Ratner D: Advances in management of dermato-fibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin 29:191-200, 2011

26. Gloster HM, Jr: Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Am Acad Der-matol 35:355-374, 1996; quiz: 375-376

27. Weinstein JM, Drolet BA, Esterly NB, et al: Congenital dermatofi-brosarcoma protuberans: variability in presentation. Arch Dermatol139:207-211, 2003

28. Maire G, Fraitag S, Galmiche L, et al: A clinical, histologic, andmolecular study of 9 cases of congenital dermatofibrosarcoma protu-berans. Arch Dermatol 143:203-210, 2007

29. Rao BK, Ahn CS: Dermatoscopy for melanoma and pigmented le-sions. Dermatol Clin 30:413-434, 2012

30. Argenziano G, Soyer HP, Chimenti S, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmentedskin lesions: results of a consensus meeting via the Internet. J AmAcad Dermatol 48:679-93, 2003

31. De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Rossari S, et al: Adding dermatoscopy tonaked eye examination of equivocal melanocytic skin lesions: effecton intention to excise by general dermatologists. Clin Exp Dermatol36:255-259, 2011

32. Rosendahl C, Tschandl P, Cameron A, et al: Diagnostic accuracy ofdermatoscopy for melanocytic and nonmelanocytic pigmented lesions.J Am Acad Dermatol 64:1068-1073, 2011

33. Menzies SW, Kreusch J, Byth K, et al: Dermoscopic evaluation ofamelanotic and hypomelanotic melanoma. Arch Dermatol 144:1120-1127, 2008

34. Noor O, 2nd, Nanda A, Rao BK: A dermoscopy survey to assess whois using it and why it is or is not being used. Int J Dermatol 48:951-952, 2009

35. Argenziano G, Puig S, Zalaudek I, et al. Dermoscopy improves accu-racy of primary care physicians to triage lesions suggestive of skin

cancer. J Clin Oncol 24:1877-1882, 2006