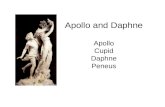

Apollo and Daphne

description

Transcript of Apollo and Daphne

Apollo and DaphneOvid, Metamorphoses I.452-567

Sarah ElleryFinal Teaching Project

UGA Summer Institute, 2013

Apollo and Daphne, Bernini, 1622-25; Galleria Borghese, RomeCredit: galleriaborghese.it

PUBLIUS OVIDIUS NASO (43 B.C. – A.D. 17/18)

• 43 BC Born 20 March at Sulmo (modern Sulmona).

• c.31 Ovid and his elder brother (by exactly one year) taken or sent to Rome to continue their education; they are granted by Augustus the rank of equites.

• c.27 Ovid assumes the toga virilis. He marries.

• c.25 Ovid’s patron is now Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus (64 BC-AD 8). He gives his first public reading. End of his formal education in rhetoric, and of his first marriage.

• 24 Death of Ovid’s brother.

• c.24-22 Ovid travels in Greece, Asia Minor, and Sicily, with the poet Macer as tutor.

Statue of Ovid in Sulmona

PUBLIUS OVIDIUS NASO (43 B.C. – A.D. 17/18)

• c.22 Trains in public administration and law.• c.21-c.16 Sits on various boards, including the tresviri and the decemviri

stlitibus iudicandis. He is close friends with the poet Propertius.• c.15 Publishes Amores. Marries for the second time, and has a daughter.

The marriage is brief, possibly owing to the death of his wife.• c.14-c.1 Writes Ars Amatoria, Remedia Amoris, Heroides, and

Medicamine Faciei Feminae, dividing his time between Rome and his country villa a few miles outside the city.

• 1 Publishes first two books of Ars Amatoria. c.1 Death of Ovid’s father, aged 90.

PUBLIUS OVIDIUS NASO (43 B.C. – A.D. 17/18)

PUBLIUS OVIDIUS NASO (43 B.C. – A.D. 17/18)

• AD c.1 Ovid’s third marriage. His wife, who is well connected and may have been in her early 20s, already has a daughter by her first husband.

• c.1-8 Writes Metamorphoses. Begins Fasti.

• 8 Banished by Augustus to Tomi.

• 9-17 In exile, completes Fasti, of which only six books survive, and writes Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto.

• 17/18 Dies during the winter, in his 60th year, and is buried on the shore of the Black Sea.

(Source: www.the-romans.co.uk/timelines/ovid.htm)

PUBLIUS OVIDIUS NASO (43 B.C. – A.D. 17/18)

Ovid’s Metamorphoses• Epic in 15 books• Bound by the theme of change:

In nova fert animus mūtātās dīcere formāscorpora: dī, coeptīs (nam vōs mūtāstis et illa)adspīrāte meīs prīmāque ab orīgine mundīad mea perpetuum dēdūcite tempora carmen. Metamorphoses I.1-4

My mind compels me to tell of forms changed into new bodies. Gods, favor my undertakings—for you have changed them, as well—and spin out a continuous poem, from the first origin of the world to my own day.

Structure of Book I• Prologue• Creation• The Four Ages• The Giants• Lycaon• The Flood• Deucalion and Pyrrha• Python• DAPHNE• Io

– Interlude: Pan and Syrinx• Phaethon

Click here to read Book I in

translation

“Apollo and Daphne”

• First “metAMORphosis” in the first book of the epic– Apollo as elegiac lover

• Reminiscent of Amores I.1– subject: Cupid and Apollo– verbal echoes– playful tone– see further discussion after section IV, “What Woman Could Resist?”

• Etiological – reward for Pythian Games

A Few Notes on Ovid’s Style• Poetic grammatical forms:

– -ēre for -ērunt– “poetic” plural– preference for -que over et– -īs for -ēs

• Vivacious, free flowing narrative – Vivid present– Metrically swift, few elisions

• Compact sense units– couplets (cf. elegy)– close relationship between the verb / participle and the noun-adjective group– caesura employed to clarify narrative rather than to create an emphatic break

• Vocabulary– Look for the ways Ovid repeats and repurposes vocabulary among and within his

stories. His word choice can provide the reader a thread with which to follow the labyrinth of interconnected themes, motifs, etc. throughout the whole work.

I. Two Archers

455

460

Prīmus amor Phoebī Daphnē Pēnēia: quem nōn fors ignāra dedit, sed saeva Cupīdinis īra. Dēlius hunc nūper victō serpente superbus, vīderat adductō flectentem cornua nervō “Quid” que ‘tibi, lascīve puer, cum fortibus armīs?” Dīxerat, “Ista decent umerōs gestāmina nostrōs, quī dare certa ferae, dare vulnera possumus hostī, quī modo pestiferō tot iūgera ventre prementem strāvimus innumerīs tumidum Pȳthōna sagittīs. Tū face nesciō quōs estō contentus amōrēs inrītāre tuā, nec laudēs adsere nostrās.”

alliteration

juxtaposition

nostrōs: “royal” we

synchesis

estō: future imperative

epithet

Pȳthōna: Greek acc.

I. Two Archers

465

470

Fīlius huic Veneris “Fīgat tuus omnia, Phoebe, tē meus arcus” ait, “quantōque animālia cēdunt cūncta deō, tantō minor est tua glōria nostrā.” Dīxit et ēlīsō percussīs āēre pennīs inpiger umbrōsā Parnāsī cōnstitit arce ēque sagittiferā prōmpsit duo tēla pharetrā dīversōrum operum: fugat hoc, facit illud amōrem; quod facit, aurātum est et cuspide fulget acūtā, quod fugat, obtūsum est et habet sub harundine plumbum.

epithet

synchesisalliteration

word picture

prodelision

KNOW THYSELF

According to the ancient travel writer Pausanias, this ancient Greek aphorism was inscribed on the pronaos (forecourt) of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. Pictured left is Apollo’s temple at Delphi, which is situated on Mt. Parnassus in central Greece. At the right is the Omphalos, or navel of the world, from the sanctuary at Delphi.

Credits: Livius.org (left); Wikimedia Commons (right)

* Does Apollo heed this

advice in this story?

Silver Drachm of Seleukos IV

OBVERSE: Seleukos IV REVERSE: Apollo, seated on

the omphalos with bow and arrow

Antioch mint, ca. 187 - 175 BCE

Credit: Wesleyan.edu (Dahl Coin Collection)

Apollo as Archer(Apollo Saettante) Roman, 100 B.C.–before A.D. 79.Discovered in Pompeii in A.D. 1817-18.

Credit: blogs.getty.edu

Apollo, Attic Red Figure kraterca. 475-425 B.C.Musée du Louvre, Paris

Apollo is pictured drawing his bow, about to kill the Niobides. Note the laurel crown and the pharetra hanging at his side.

Credit: theoi.com

II. The Arrows Fly

475

480

Hoc deus in nymphā Pēnēide fīxit, at illō laesit Apollineās trāiecta per ossa medullās: prōtinus alter amat, fugit altera nōmen amantis silvārum latebrīs captīvārumque ferārum exuviīs gaudēns innūptaeque aemula Phoebēs; vitta coercēbat positōs sine lēge capillōs. Multī illam petiēre, illa āversāta petentēs inpatiēns expersque virī nemora āvia lustrat nec, quid Hymēn, quid Amor, quid sint cōnūbia cūrat.

patronymic

anaphora, tricolon

Girl wearing the vitta, or headband. From William Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities.Credit: LacusCurtius.org

synchesis

Apollineās: neologism

synchesis

485

Saepe pater dīxit “Generum mihi, fīlia, dēbēs”, saepe pater dīxit “dēbēs mihi, nāta, nepōtēs”: illa velut crīmen taedās exōsa iugālēs pulchra verēcundō suffūderat ōra rubōre inque patris blandīs haerēns cervīce lacertīs, “Dā mihi perpetuā, genitor cārissime,” dīxit “virginitāte fruī: dedit hoc pater ante Diānae.” Ille quidem obsequitur; sed tē decor iste, quod optās, esse vetat, vōtōque tuō tua forma repugnat.

II. The Arrows Fly

“golden line”

word picture

anaphora, synchesis, 2x chiasmus

alliteration

polyptoton: the repetition of a word or root in different grammatical forms within the

same sentence.

If the Verse does consist of two Adjectives, two Substantives and a Verb only, the first Adjective agreeing with the first Substantive, the second with the second, and the Verb placed in the midst, it is called a Golden Verse: as, a b V A BLurida terribiles miscent aconita novercae (Ovid, Metamorphoses 1.147) “murderous stepmothers mixed deadly aconite”

a b V A B

“Golden Line”

aurea purpuream subnectit fibula vestem "a golden clasp bound her purple cloak”

(Virgil, Aeneid 4.139)

The golden line is variously defined, but most uses of the term conform to the oldest known definition from Burles' Latin grammar of 1652:

Here the adjectives (a, b) are placed at the beginning of the line, and the nouns (A, B) at the end. Note that in each case the synchesis is purposeful, emphasizing the meaning of the line (mixing poison and binding a cloak).

• The term "golden line" did not exist in antiquity. • Winbolt, the most thorough commentator on the golden line,

described the golden line as a combination of poetic tendencies in Latin hexameter– the preference for placing adjectives near the beginning of the line and nouns emphatically near the end.

• The golden line is a form of hyperbaton, or the deviation from normal or logical word order for poetic effect.

• Some scholars also consider lines with a chiastic pattern to be “golden” (a-b-V-B-A), but others instead call this a “silver line”.

“Golden Line”

“Golden Line”

K. Mayer, "The Golden Line: Ancient and Medieval Lists of Special Hexameters and Modern Scholarship," in C. Lanham, ed., Latin Grammar and Rhetoric: Classical Theory and Modern Practice, Continuum Press, 2002, pp. 139-179.

490 Phoebus amat vīsaeque cupit cōnūbia Daphnēs, quodque cupit, spērat, suaque illum ōrācula fallunt; utque levēs stipulae dēmptīs adolentur aristīs, ut facibus saepēs ardent, quās forte viātor vel nimis admōvit vel iam sub lūce relīquit, sīc deus in flammās abiit, sīc pectore tōtō ūritur et sterilem spērandō nūtrit amōrem. Spectat inōrnātōs collō pendēre capillōs et “Quid, sī cōmantur?” ait;

III. Apollo in Love

495

irony

epic simile

Daphnēs: Gk. gen.

500

videt igne micantēs

sīderibus similēs oculōs, videt ōscula, quae nōn est vīdisse satis; laudat digitōsque manūsque bracchiaque et nūdōs mediā plūs parte lacertōs: sīqua latent, meliōra putat. Fugit ōcior aurā illa levī neque ad haec revocantis verba resistit: “Nympha, precor, Pēnēi, manē! Nōn īnsequor hostis; nympha, manē! Sīc agna lupum, sīc cerva leōnem, sīc aquilam pennā fugiunt trepidante columbae, hostēs quaeque suōs; amor est mihi causa sequendī.

III. Apollo in Love

505

simile, anaphora, alliterationlitotes, polysyndeton

Note the placement of videt, laudat, and fugit at the beginning of their clauses. What is the effect?

synchesis

anaphora, synchesis, simile, tricolon

Pēnēi: Gk. voc. (not a dipthong)

metaphor

chiasmus

EKPHRASIS: description in literary works, often used in epic

• Often highly visual– What visual cues does Ovid give in this story?

• Gives the reader a “gaze”, often through an internal viewer– cf. Temple of Juno in Bk. I of the Aeneid

– Through whose gaze do we “see” Daphne?

510

“Mē miserum! Nē prōna cadās, indignave laedī crūra notent sentēs, et sim tibi causa dolōris. Aspera, quā properās, loca sunt: moderātius, orō, curre fugamque inhibē: moderātius īnsequar ipse. Cui placeās, inquīre tamen; nōn incola montis, nōn ego sum pāstor, nōn hīc armenta gregēsque horridus observō. Nescīs, temerāria, nescīs, quem fugiās, ideōque fugis. Mihi Delphica tellūs et Claros et Tenedos Patarēaque rēgia servit;

IV. What Woman Could Resist?

515

Nē: take with cadās (2nd person jussive = imperative), notent, sim

tricolon

tricolon, anaphora

anaphora

polysyndeton

polyptoton

epizeuxis

epizeuxis- repetition of words or phrases with few or no words betweene.g. “Please Please Me” –The Beatles

520

Iūppiter est genitor. Per mē, quod eritque fuitque estque, patet; per mē concordant carmina nervīs. Certa quidem nostra est, nostrā tamen ūna sagitta certior, in vacuō quae vulnera pectore fēcit. Inventum medicīna meum est, opiferque per orbem dīcor, et herbārum subiecta potentia nōbīs: ei mihi, quod nūllīs amor est sānābilis herbīs, nec prōsunt dominō, quae prōsunt omnibus, artēs!”

IV. What Woman Could Resist?

Review: Look again at Apollo’s speech, and find examples of caesura and diaeresis. Why might there be so many breaks in these lines compared to the narration?

anaphoraalliterationprodelisionenjambment, polyptoton

prodelision

irony

nōbīs: dat. w/ subiecta

How did Apollo come to have the lyre?

• Hermes, the herald of the Olympian gods, is the son of Zeus and the nymph Maia, daughter of Atlas and one of the Pleiades. Hermes is the god of shepherds, land travel, merchants, weights and measures, oratory, literature, athletics and thieves, and known for his cunning and shrewdness. Most importantly, he is the messenger of the gods. Besides that he was also a minor patron of poetry. He was worshiped throughout Greece -- especially in Arcadia -- and festivals in his honor were called Hermoea.

• According to legend, Hermes was born in a cave on Mount Cyllene in Arcadia. Zeus had impregnated Maia at the dead of night while all other gods slept. When dawn broke amazingly he was born. Maia wrapped him in swaddling bands, then, resting herself, fell fast asleep. Hermes, however, squirmed free and ran off to Thessaly. This is where Apollo, his brother, grazed his cattle. Hermes stole a number of the herd and drove them back to Greece. He hid them in a small grotto near to the city of Pylos and covered their tracks.

• Before returning to the cave he caught a tortoise, killed it and removed its entrails. Using the intestines from a cow stolen from Apollo and the hollow tortoise shell, he made the first lyre. When he reached the cave he wrapped himself back into the swaddling bands.

• When Apollo realized he had been robbed he protested to Maia that it had been Hermes who had taken his cattle. Maia looked to Hermes and said it could not be, as he is still wrapped in swaddling bands. Zeus the all-powerful intervened saying he had been watching and Hermes should return the cattle to Apollo. As the argument went on, Hermes began to play his lyre. The sweet music enchanted Apollo, and he offered Hermes to keep the cattle in exchange for the lyre.

• Apollo later became the grand master of the instrument, and it also became one of his symbols. Later while Hermes watched over his herd he invented the pipes known as a syrinx (pan-pipes), which he made from reeds. Hermes was also credited with inventing the flute. Apollo also desired this instrument, so Hermes bartered with Apollo and received his golden wand, which Hermes later used as his heralds staff. (In other versions Zeus gave Hermes his heralds staff).

Source: Ron Leadbetter, pantheon.org

HERMES APOLLO HERAKLES

Attic Red Figure Kylix, ca. 500 B.C.; Antikenmuseen, Berlin, Germany

Elegiac Poetry• elegiac couplet (hexameter / pentameter)

- u u | - u u | - u u | - u u | - u u | - - - u u | - u u | - || - u u | - u u | -

• Greek origins• most popular type of poetry in Ovid’s Rome

– Catullus, Propertius, Tibullus• love is common theme

– Paraclausithyron, exclusus amator

Read Amores I.1(click for link)

This is sort of what Daphne must have felt like… (click for video)

525 Plūra locūtūrum timidō Pēnēia cursū fūgit cumque ipsō verba inperfecta relīquit, tum quoque vīsa decēns; nūdābant corpora ventī, obviaque adversās vibrābant flāmina vestēs, et levis inpulsōs retrō dabat aura capillōs, auctaque forma fugā est. Sed enim nōn sustinet ultrā perdere blanditiās iuvenis deus, utque monēbat ipse amor, admissō sequitur vestīgia passū.

V. The Pace Quickens

530

golden line!

locūtūrum (eum)

prodelision

amor (or Amor!)

alliteration

535

Ut canis in vacuō leporem cum Gallicus arvō vīdit, et hic praedam pedibus petit, ille salūtem (alter inhaesūrō similis iam iamque tenēre spērat et extentō stringit vestīgia rostrō, alter in ambiguō est, an sit conprēnsus, et ipsīs morsibus ēripitur tangentiaque ōra relinquit): sīc deus et virgō; est hic spē celer, illa timōre.

V. The Pace Quickens

word picture

enjambment, synchesis

epizeuxis

an: introduces a deliberative subjunctiveēripitur: middle voice

epic simile

subject performs AND receives the reflexive pronounaction of the verb

What is the Greek middle voice? What does Latin use instead?

synchesis 2x

540 Quī tamen īnsequitur, pennīs adiūtus amōris, ōcior est requiemque negat tergōque fugācis inminet et crīnem sparsum cervīcibus adflat. Vīribus absūmptīs expalluit illa citaeque victa labōre fugae “Tellūs,” ait, “hīsce vel istam, [victa labōre fugae spectāns Pēnēidās undās] quae facit ut laedar, mutandō perde figūram!

VI. Daphne’s Last Request

544a 545

polysyndetonenjambment

istam (figuram)

547a

Fer, pater,” inquit “opem, sī flūmina nūmen habētis! quā nimium placuī, mutandō perde figūram!” [quā nimium placuī, Tellūs, ait, hīsce vel istam] Vix prece fīnītā torpor gravis occupat artūs: mollia cinguntur tenuī praecordia librō, in frondem crīnēs, in rāmōs bracchia crēscunt; pēs modo tam vēlōx pigrīs rādīcibus haeret, ōra cacūmen habet: remanet nitor ūnus in illā.

VI. Daphne’s Last Request

550

quā (figuram)

scan

synchesis

antithesis

* Note that Daphne’s prayer, like Apollo’s to her, has many caesurae and diaereses. Why?

internal rhyme

Credit:nga.gov

• Antonio del Pollaiuolo, late 15th century; oil on wood; The National Gallery, London

• Renaissance: classicizing, allegory

• What aspects of this portrayal are similar to or different from the Ovidian version?

• What are the limitations in portraying this myth visually?

Pollaiuolo: Apollo and Daphne

Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne

• Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1622-25; Rome, Galleria Borghese

• Baroque: reaction against the pure, straight lines of the Classical period

Click to view the sculpture in the round (narration in Italian)

Credit: Cavetocanvas.com

Credit: www.mcah.columbia.e

du

Credits: www.mcah.columbia.edu

Apollo Belvedere

• Roman copy of a Greek original by Leochares, ca. 120-140 (Hadrianic); Rome, Vatican Museum.

• Compare this Apollo’s staid posture and classical lines with his portrayal by Bernini.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini

(1598-1680)

Self portrait, ca. 1623Rome: Galleria Borghese

Baroque Architecture: Baldacino, St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome

Baroque Architecture: Bernini, Fontana dei Quattro Fiume,

Piazza Navona, Rome

Baroque Architecture: Trevi Fountain, Rome

1685-1750

Baroque Music:

555

Hanc quoque Phoebus amat positāque in stīpite dextrā sentit adhūc trepidāre novō sub cortice pectus conplexusque suīs ramos, ut membra, lacertīs ōscula dat lignō: refugit tamen ōscula lignum. Cui deus “At quoniam coniūnx mea nōn potes esse, arbor eris certē” dīxit “mea. Semper habēbunt tē coma, tē citharae, tē nostrae, laure, pharetrae;

VII. Apollo’s Eternal Love

word pictures…

note the placement of the anatomical words

chiasmus, synchesis, polypton, epizeuxisalliteration

anaphora

www.theoi.com

560 tū ducibus Latiīs aderis, cum laeta triumphum vōx canet et vīsent longās Capitōlia pompās. Postibus Augustīs eadem fīdissima custōs ante forēs stābis mediamque tuēbere quercum, utque meum intōnsīs caput est iuvenāle capillīs, tū quoque perpetuōs semper gere frondis honōrēs.” Fīnierat Paeān: factīs modo laurea rāmīs adnuit utque caput vīsa est agitāsse cacūmen.

VII. Apollo’s Eternal Love

565

transferred epithet

personification

mediam: word picture

simile, chiasmus

epithet

enjambment

The Laurel• Laurus nobilis

– evergreen, aromatic• Uses

– cooking and ornamental herb– medicinal (salve for wounds, folk

remedy for ear/headaches, high blood pressure, cough, poison ivy/oak and stinging nettle, arthritis)

• Ancient symbolism– healing– prophecy

• Pythia– victory

• Pythian Games• cf. Baccalaureate, “rest on laurels”

– poet’s calling• cf. poet laureate

– Bible: resurrection and eternal life

Credit: Theoi.com

Attic Red-figure. Themis (Pythia) - Aegeus Consults the Pythia Seated on a Tripod. By the Kodros Painter, c. 440-430 B.C. Antiken-sammlung, Berlin, Germany. Credit: Ancienthistory.about.com.

The Pythia, Apollo’s priestess at Delphi, was preeminent among ancient oracles. Celibate for life, she gave prophecies on a single day for nine months of the year. She sat on the tripod where hallucinogenic vapors may have put her in an altered state. Her utterances came forth in hexameters (the “Pythian meter”).

In this image, the Pythia holds the laurel (symbol of Apollo) in her right hand and stares intently into the phiale dish as she prophecies to Aegeus.

The Laurel: Mythic Sources

The Laurel: Mythic SourcesFrom Theoi.com:• Ovid places the aetion in the Valley of Tempe in

Thessaly, which is where the river Peneios flows into the Aegean sea. In the valley was a sacred laurel tree, the fronds of which were used to crown the victors of the Pythian games. The contests were originally musical, but athletic events were added in 585 B.C.

• In a festival at Delphi, a branch of a sacred laurel tree was fetched from the Thessalian vale of Tempe. This rite would suggest that the Thessalian version of the Daphne myth was the older than the one told by Ovid as an aetion.

• There was also a Delphic myth about Daphnis, an oreiad nymph who was Gaia's prophetic priestess at Delphoi before Apollo took control of the oracle.

Valley of Tempe and the Peneus River

The Laurel: Mythic Sources

Mosaic from Antioch, House of Menander; ca. 2nd - 3rd century A.D.

Antakya Museum, Antakya, Turkey

The Laurel: Mythic SourcesFrom Theoi.com:• Pausanias, Description of Greece 10. 7. 8 (trans. Jones) (Greek travelogue

C2nd A.D.) : "The reason why a crown of laurel is the prize for a Pythian victory is in my opinion simply and solely because the prevailing tradition has it that Apollo fell in love with the daughter of Ladon [Daphne].”

• Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana 1. 16 (trans. Conybeare) (Greek biography C1st to 2nd A.D.) : "[In Antiokhos (Antioch) in Asia Minor is] the temple of Apollo Daphnaios, to which the Assyrians attach the legend of Arkadia. For they say that Daphne, the daughter of Ladon, there underwent her metamorphosis, and they have a riving flowing there, the Ladon, and a laurel tree is worshipped by them which they say was substituted for the maiden.”

• Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 203 (trans. Grant) (Roman mythographer C2nd A.D.) : "When Apollo was pursuing the virgin Daphne, daughter of the river Peneus, she begged for protection from Terra [Gaia the Earth], who received her, and changed her into a laurel tree. Apollo broke a branch from it and placed it on his head."

The Laurel: Mythic SourcesFrom Theoi.com:• Nonnus, Dionysiaca 33. 210 ff (trans. Rouse) (Greek epic C5th A.D.) :

"She told how the knees of that unwedded Nymphe [Daphne] fled swift on the breeze, how she ran once from Phoibos quick as the north wind, how she planted her maiden foot by the flood of a long-winding river, by the quick stream of Orontes, when the Earth (Gaia) opened beside the wide mouth of a marsh and received the hunted girl into her compassionate bosom . . . the god never caught Daphne when she was pursued, Apollo never ravished her . . . and [he] always blamed Gaia (earth) for swallowing the girl before she knew marriage.”

• Nonnus, Dionysiaca 42. 386 ff :"How the daughter of Ladon [Daphne], that celebrated river, hated the works of marriage and the Nymphe became a tree with inspired whispers, she escaped the bed of Phoibos but she crowned his hair with prophetic clusters."

Discussion

• Reactions?• What metamorphoses occur in this tale?

– What is the impetus of these changes?– How has Ovid prepared us for these metamorphoses before they occur? – Are they in any way contrary to our expectations?

• How do Apollo and Daphne react to these transformations?– Who is sympathetic? With whom do we identify?

• How does Ovid “paint” this story? What visual cues does he give?• How does Ovid directly reference Augustus in this story? How does

he indirectly reference him? – Are they favorable comparisons? Why or why not?

The decoration of coins was a practical method of conveying propaganda throughout the empire, and Augustus made frequent use of the laurel as a symbol of victory in his coinage. Coin a shows the House of Augustus, flanked by two laurel trees with the oak wreath above the doors (aureus from Rome, 12 B.C.). Coins b and c (both aurei from Spain and Gaul, both 19/18 B.C.) again depict the two laurels , and on coin c, laurels grow on either side of the clipeus virtutis.

What do the laurels on the front of Augustus’s house symbolize?Why was this such an important symbol for him?

Credit: Paul Zanker

Res Gestae Divi AugustiIn consulatu sexto et septimo, postquam bella civilia exstinxeram, per consensum universorum potitus rerum omnium, rem publicam ex meā potestate in senatūs populique Romani arbitrium transtuli. Quo pro merito meo senatūs consulto Augustus appellatus sum et laureis postes aedium mearum vestiti publice coronaque civica super ianuam meam fixa est et clupeus aureus in curia Iulia positus, quem mihi senatum populumque Romanum dare virtutis clementiaeque et iustitiae et pietatis causa testatum est per eius clupei inscriptionem. Post id tempus auctoritate omnibus praestiti, potestatis autem nihilo amplius habui quam ceteri qui mihi quoque in magistratu conlegae fuerunt.

--Augustus, Res Gestae 34

In my sixth and seventh consulships, when I had extinguished the flames of civil war, after receiving by universal consent the absolute control of affairs, I transferred the republic from my own control to the will of the senate and the Roman people. For this service I was named Augustus by decree of the Senate. The doorposts of my house were officially decked out with young laurel trees, the corona civica was placed over the door, and in the Curia Iulia was displayed the golden shield (clipeus virtutis), which the Senate and the people granted me on account of my bravery, clemency, justice, and piety (virtus, clementia, iustitia, pietas), as is inscribed on the shield itself. After that time I took precedence of all in rank, but of power I possessed no more than those who were my colleagues in any magistracy.

Clipeus Virtutis

Replica of the honorary shield of Augustus, awarded to him by the Senate in 27 B.C. and displayed in the Curia; Museum of Arles.

Credit: Livius.org

Mausoleum of Augustus

Credit: The Online Database of Ancient Art

Click here for more information about the reconstruction of the mausoleum.

Another reconstruction:

Upper right: The Mausoleum of Augustus today. Lower right: Google Earth view of the mausoleum. Below: The Ara Pacis, located in the mausoleum complex with the Horologium.

Credit: LacusCurtius.org

Ovid’s Nachleben(“Survival” or “afterlife”)

And now the work is done, that Jupiter’s anger, fire or sword cannot erase, nor the gnawing tooth of time. Let that day, that only has power over my body, end, when it will, my uncertain span of years: yet the best part of me will be borne, immortal, beyond the distant stars. Wherever Rome’s influence extends, over the lands it has civilised, I will be spoken, on people’s lips: and, famous through all the ages, if there is truth in poet’s prophecies, –vivam - I shall live. (Trans. A.S. Kline)

Iamque opus exegi, quod nec Iovis ira nec ignisnec poterit ferrum nec edax abolere vetustas.cum volet, illa dies, quae nil nisi corporis huiusius habet, incerti spatium mihi finiat aevi:parte tamen meliore mei super alta perennis 875astra ferar, nomenque erit indelebile nostrum,quaque patet domitis Romana potentia terris,ore legar populi, perque omnia saecula fama,siquid habent veri vatum praesagia, vivam.

In the final lines of the Metamorphoses, Ovid points to the future of his work:

Ovid’s NachlebenMetamorphosing the Metamorphoses

• Manuscript tradition • Ancient admirers and imitators• Middle Ages

– new cultural preeminence in 12th – 13th centuries (“Aetas Ovidiana”)– courtly love; Chretien de Troyes– moralizing trend (Ovide Moralise)– Chaucer, Boccaccio, Dante

• Renaissance– Arthur Golding translation– Milton, Spenser, Shakespeare– Opera (Dafne, 1598); painting and sculpture

• Modern period• 17th - 18th centuries: Dryden, Pope, Goethe, Keats • Romanticism: low point in Ovidian studies• 20th century: James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, Franz Kafka; psychology

• Contemporary revival

Credits: goodreads.com

WATCH A TRAILER(click here)

Zimmerman finished the play in 1998, and it opened on Broadway

in 2002

Landscape with the Fall of IcarusBreugel, ca. 1558

Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Belgium

“Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” --William Carlos WilliamsAccording to Brueghelwhen Icarus fellit was spring

a farmer was ploughinghis fieldthe whole pageantry

of the year wasawake tinglingwith itself

sweating in the sunthat meltedthe wings' wax

unsignificantlyoff the coastthere was

a splash quite unnoticedthis wasIcarus drowning

“Musee des Beaux Arts” --W. H. Auden

About suffering they were never wrong,The old Masters: how well they understoodIts human position: how it takes placeWhile someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waitingFor the miraculous birth, there always must beChildren who did not specially want it to happen, skatingOn a pond at the edge of the wood:They never forgotThat even the dreadful martyrdom must run its courseAnyhow in a corner, some untidy spotWhere the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer's horseScratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns awayQuite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman mayHave heard the splash, the forsaken cry,But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shoneAs it had to on the white legs disappearing into the greenWater, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seenSomething amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

“The Tree” – Ezra Pound, 1921-24

I stood still and was a tree amid the wood,Knowing the truth of things unseen before;Of Daphne and the laurel bowAnd that god-feasting couple oldthat grew elm-oak amid the wold.'Twas not until the gods had beenKindly entreated, and been brought withinUnto the hearth of their heart's homeThat they might do this wonder thing;Nathless I have been a tree amid the woodAnd many a new thing understoodThat was rank folly to my head before.

“Where I Live in the Honorable House of the Laurel Tree” – Anne Sexton, 1960I live in my wooden legs and O

my green green hands.Too lateto wish that I had not run from you, Apollo,blood moves still in my bark bound veins,I, who ran nymph foot to root in flight,have only this late desire to arm thetrees I lie within. The measure that I have lostsilks my pulse. Each century, the trickeriesof need pain me everywhere.Frost taps my skin and I stay glossedin honor, for you are gone in time. The airrings for you, for that astonishing riteof my breathing tent undone with your light.I only know how this untimely lust has tossedflesh at the wind forever and moved my fearstoward the intimate Rome of the myth we crossed.I am a fist of my uneaseas I spill toward the stars in the empty years.I build the air with the crown of honor; it keysmy out of time and luckless appetite.You gave me honor too soon, Apollo.There is no one left who understandshow I waithere in my wooden legs and Omy green green hands.

“Ovid in the Third Reich” -- Geoffrey Hill, 1968

non peccat, quaecumque potest peccasse negare, solaque famosam culpa professa facit.

-- Amores, III, xiv

I love my work and my children. God Is distant, difficult. Things happen. Too near the ancient troughs of blood Innocence is no earthly weapon.

I have learned one thing: not to look down So much upon the damned. They, in their sphere, Harmonize strangely with the divine Love. I, in mine, celebrate the love-choir.

“Daphne” – Alicia E. Stallings, 1999 Poet, Singer, Necromancer—I cease to run. I halt you here,Pursuer, with an answer: Do what you will.What blood you've set to music ICan change to chlorophyll, And root myself, and with my toesWind to subterranean streams.Through solid rock my strength now grows. Such now am I, I cease to eat,But feed on flashes from your eyes;Light, to my new cells, is meat. Find then, when you seize my armThat xylem thickens in my skinAnd there are splinters in my charm. I may give in; I do not lose.Your hot stare cannot stop my shivering,With delight, if I so choose.

Unless otherwise specified, all images are from Wikimedia Commons.

• A.S. Kline, “Ovid’s Metamorphoses”: http://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Ovhome.htm#askline

• Mythology and images: www.theoi.com

•Res Gestae text and translation: www.LacusCurtius.org

• Zanker, Paul. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1988.

• Poems by William Carlos Williams and W.H. Auden:http://english.emory.edu/classes/paintings&poems/auden.html

• Poem by Geoffrey Rich: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/178125

• Poems by Ezra Pound and Anne Sexton: www.poemhunter.com

• Poem by A.E. Stallings: www.poemtree.com

Sources