APIF Ev' - Auburn University

Transcript of APIF Ev' - Auburn University

' APIF Ev'

I

~ 4%

Greenleaf Tabasco,

a New Tobacco Etch

Virus Resistant

Tabasco Pepper Variety

( Ca psicum [rutescens L.)

A G RI CU LTUJR AL F=X P FRI M EN T S T ATIO NE. V. Smith, Director AUBU RN U N IV I RSITY Auburn, Alabama

SUMMARY

A new tobacco etch virus (TEV) re-sistant Tabasco pepper variety (Cap-sicum frutescens L.) named GreenleafTabasco (Tabasco G) has been devel-oped at the Auburn University Agricul-tural Experiment Station. TEV, which iswidely distributed in the South on sola-naceous host plants and transmitted byaphids, causes a serious wilt disease ofthe commercial Tabasco variety, threat-

ening its survival and consequently thatof the Tabasco hot sauce industry. Thenew variety removes this threat from theindustry. In addition, the new varietyhas resistance to ripe rot, a more con-centrated fruit set, a darker red maturefruit color, a brighter yellow immaturefruit color, and a higher pungency.

Two Indian pepper introductions of C.chinense Jacquin from Peru, P.I. 152225and P.L 159236, were the sources ofthese improvements.

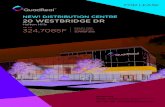

ON THE COVERPlant at top is the tobacco etch virus (TEV) resistant Greenleaf Tabasco. Center left

is P. I. 152225 with orange red fruit. Center right is P. I. 159236 with glossy, darkchocolate colored fruit. Note that up to three fruits are set per axil in Capsicum chinenseand up to two in Capsicum frutescens. Bottom left shows fruit of the TEV resistant Green-leaf Tabasco, at right is fruit of the TEV susceptible commercial Tabasco variety showingthe typical ripe rot symptom on the third fruit from the right.

FIRST PRINTING 3M, DECEMBER 1970

Greenleaf Tabasco, a New Tobacco Etch VirusResistant Tabasco Pepper Variety

(Capsicum [rutescens L.)

W. H. GREENLEAF, J. A. MARTIN, J. G. LEASE,E. T. SIMS and L. O. VAN BLARICOM 2

,3

A CCOuNTS of the McIlhenny Companyof Avery Island, Louisiana (7) and ofthe Trappey and Sons Company of NewIberia, Louisiana (15), indicate thatseeds of a fiery hot Indian pepper wereintroduced into Louisiana, probably-fromthe State of Tabasco in Mexico, about1848.

The fine qualities of this pepper formaking a vinegar extract, used as a con-diment and as an aid to digestion, weresoon recognized, around New Orleans.The pepper itself was named Tabasco forthe state from whence it came. How-ever, it was not until after the Civil Warthat Edmund Mcllhenny, a New Orleansbanker and gourmet, perfected a super-ior hot sauce made from the fermentedmash of red ripe Tabasco peppers. Heobtained a patent for the process in1870.

McIlhenny's Tabasco sauce, which ismade on the family plantation on Avery

' The senior author acknowledges grantsupport from the McIlhenny Company,Avery Island, Louisiana.

' Respectively, Professor, Department ofHorticulture, Auburn University; AssociateProfessor of Horticulture; Nutrition Asso-ciate, Food Science and Biochemistry; As-sociate Professor of Horticulture; and Pro-fessor of Horticulture, all of Clemson Uni-versity. Dr. J. G. Lease is currently Pro-fessor of Foods and Nutrition, School of

Island, soon became internationally fa-mous. This salt dome island providesnot only the Tabasco peppers but alsothe large quantity of salt needed for thefermentation process by which this sauceis made. The pepper mash with saltadded is packed into 50-gallon Kentuckywhite oak barrels, covered with a layerof salt, and allowed to ferment for 3years. The mash is then filtered, homo-genized, diluted 1:3 with vinegar, andbottled (9, 10). Since 1946, the name"Tabasco" has been the permanent trade-mark for the hot sauce of the McIlhennyCompany (8).

In addition to its culinary history, theTabasco pepper has an interesting"virus" history that began at the GeorgiaAgricultural Experiment Station, Experi-ment, Georgia in 1945. There the Ta-basco variety was included in a collec-tion of peppers being screened by Green-leaf for resistance to the bacterial leafspot disease for breeding a resistant

Home Economics, Montana State Univer-sity, Bozeman, Montana.

SThis publication is a cooperative effortof the Departments of Horticulture of Au-burn University and of Clemson University.Greenleaf developed the new GreenleafTabasco pepper variety; Martin made thechemical pungency tests; Lease made quali-tative and quantitative determinations ofthe various fruit pigments; Sims determinedjuice yields; and Van Blaricomb determinedfruit color.

[3]

pimiento. The Tabasco plants, however,died from an unknown wilt disease earlyin July, just as they were beginning tofruit. Of the many peppers in the collec-tion, only Tabasco was thus affected. In1946, the disease reappeared, killing allplants except the two which had beencovered with insect-proof cloth cages.In 1947, Greenleaf moved to the Agri-cultural Experiment Station at Auburn,where the disease was also observed inthe field. Prior to 1947, Weimer, formerlyUSDA plant pathologist at Experiment,Georgia, had suggested that the diseasehad the characteristics typical of a virusdisease, thus focusing attention on thispossibility.

In 1949, Perry (1) succeeded in trans-mitting the disease to two of four healthyTabasco plants by leaf inoculation withextract from a wilted Tabasco plant with-out the use of carborundum. However,it was Holmes (4,5), of the RockefellerInstitute for Medical Research, who firstidentified the causal agent as tobaccoetch virus (TEV). He obtained the virusfrom Alabama pepper samples sent himby Greenleaf (1) in 1950. In the fieldthe virus is spread by aphids which ac-counts for the high percentage of in-fected plants. The unique wilt reactionof Tabasco has since proved to be diag-nostic for TEV (3).

Meanwhile, Younkin of the CampbellSoup Company, Riverton, N.J. reportedin personal correspondence that P. I.152225 from Peru, a variety of Capsicumchinense Jacquin, had remained free ofsymptoms following inoculation withTEV. Greenleaf (2) subsequentlyshowed that this was not immunity buta high level of resistance. This wasproved by a slow rate of virus increasein inoculated plants and by their toler-ance of the virus. The "etch" wilt reac-tion of Tabasco was dominant in the F 1hybrid (P.I. 152225 x Tabasco) and re-sistance was inherited as a monogenicrecessive trait (2).

Holmes originally prompted the breed-ing effort by Greenleaf to develop a

TEV resistant Tabasco pepper. He an-ticipated that the disease would becomeimportant to the Tabasco industry inLouisiana, a prediction that has sincecome true. Joseph Montelaro, LouisianaState University Extension Service, wrotein May, 1959: "We are having a lot oftrouble with the Tabasco variety. I knowthat the growers in the St. Martin areatell me that if something is not donethat they will have to discontinue pro-ducing Tabasco pepper. You know thatthis is a big business in Louisiana." Bythis time, Greenleaf had begun to breedTEV resistant Tabasco type peppers atAuburn, but they were not yet commer-cially acceptable for fruit type. Now ahighly desirable TEV resistant Tabascovariety, illustrated on Page 1, has beendeveloped and is ready for release to theindustry.

ORIGIN OF GREENLEAF TABASCO

Tabasco is probably the only commer-cially important pepper variety of thespecies Capsicum frutescens L. in theU.S. trade. Most other varieties are ofC. annuum L. (12). In the breeding ofTabasco G, two strains of the Tabascovariety were used. In the first crossesa strain of the Reuter Seed Company ofNew Orleans was used and later oneof the McIlhenny Company. Two TEVand ripe rot resistant Indian peppercultivars from Peru, P.I. 152225 andP.I. 159236, both of C. chinense Jacquin(see illustration) contributed not onlyTEV and ripe rot resistance to the newTabasco, but also improved fruit char-acteristics. This was possible becauseC. chinense crosses readily with C. fru-tescens, and no serious sterility barrierwas encountered (13). Up to four back-crosses to Tabasco were made, withalternating selfed generations beingscreened for "etch" resistance after eachbackcross. Interline crosses were alsomade at the third backcross level toconcentrate the genes for other desirableplant and fruit characteristics. The pedi-

[4]

PEDIGREE OF GREENLEAF TABASCO

o 950 C. chinense C. frutescens C. chinensePI. 152225 var. Tabasco PI-159236

o F F2BC3 Interline crosses F

o TEV F2

1F3 (ii Fl 61139 141 148 151 FBD

11956 F1B BLl

TEV F Double crossC2

o F3 14 FBC3

RC2 F, iI ~FtTEV F Tabasco

O 196o FiBC3 1967 R BC4 F4BC3ITE

V FtI@ TVF2F2 1F6

0 1970 TEV F3 TEV FtBulked l ines 70-1 70-516-1717A

(F4 seed) (F2 seed)

Abbreviations N

PI,P27P3 =Parents

R to F6 = Filial generations TABASCO

BDt to BC4= Back crosses

TEV= TEV screened generations

@0 Number of generations

gree offigure.

Tabasco G is presented in the

CHARACTERISTICS AND PERFORMANCE

Plant Habit and Productivity. Twodistinct growth habit types, based onthe kind of branching, occur in the orig-inal, Tabasco variety. The more desir-able type produces plants with a fiat

top, bearing erect fruits well exposed forpicking. The other type bears fruit's inracemes with drooping branches. Plantsof the first type are usually taller, andwhen in full fruit present a stunning ap-pearance. The fiat top habit seems dif-ficult to stabilize genetically. TabascoC, like the original variety, is a mixtureof both plant types.

[5]

TABLE 1. COMPARATIVE PRODUCTIVITY OF SINGLE PLANT SELECTIONS OF TABASCOAND TABASCO G IN 1969

Variety and line Total Total fruit Per cent Av. fruitfruit weight fruit weight ripe fruit weight

No. G. No. G. Pct. G.Tabasco 69-13 500 508 1.0060

69-18 840 860 1.028869-13 1,712 1,606 852 740 46.1 0.9381

Tabasco G------------ 69-2 2,041 1,910 1.006069-11 2,10831 2,142 1,328 1,438 67.1 1.0185

SBest single plant selections of each variety in the field.

Several observers independently agreedthat Tabasco G seemed more produc-tive than the original variety. This wasverified by counting and weighing thefruit of several of the better plants ofeach. In 1969, the best Tabasco G se-lection had 23 per cent more fruits thanthe best Tabasco selection and 33 percent more fruit weight, Table 1. Theheavier fruit set of Tabasco G is prob-ably a result of a greater fruit densityper unit length of stem.

Fruit Abscission. Easy abscission ofthe fruit is a characteristic of economicimportance because it facilitates picking.This trait is genetically dominant overhard abscission (11) but various inter-mediate degrees occur in the originalTabasco variety. Despite rigorous selec-tion for this trait, Tabasco G is stillvariable in abscission but probably nomore so than Tabasco itself. Ease ofabscission improves with fruit maturityand comparisons between plants or varie-

ties must be made with fruits of com-parable maturity.

Fruit Size, Weight, and Shape. Thetwo varieties are similar in fruit sizeand weight, Table 2. In three years'

comparisons there was little difference infruit length, but Tabasco G fruits weresignificantly broader, Table 2. Over theyears Tabasco G was selected for abroadly conical fruit shape with arounded, smooth stylar tip in preferenceto slender fruits with sharper tips thatwould tend to catch on processingscreens.

Maturity. Tabasco and Tabasco Gare late maturing varieties that areadapted only to areas having a longgrowing season. When sown in peatpots early in February and transplantedto the field in the middle of April, har-vesting of ripe fruit can begin in themiddle of August. Harvest of immaturefruit in the yellow-green stage couldstart 2-3 weeks earlier. The plants con-

TABLE 2. COMPARATIVE SIZE AND WEIGHT OF MATURE FRUITS OF TABASCO

AND OF TABASCo G

Variety and year Fruit Av. fruit Av. fruitFut length width

mm80.42 b30.09 b81.76 a80.46 b29.46 b29.57 b

mm-

7.88 b8.14b8.22 b9.03 a8.66 a8.82 a

Fruit

No.1,484

Av. fruitweight

0.8430

500 1.2080886 1.0963

1,500 1.1955

,2 Comparisons should be by years. Values followed by different letters differ significantlyat P < 0.01.

SFigures are meas are means of bulk weights. A larger fruited strain of Tabasco was used in1968 and 1969 than in in 1967.

[6]

TabascoTabascoTabascoTabasco GTabasco GTabasco G

196719681969196719681969

No.150107100200108200 v v

TABLE 3. FRUIT COLOR, JUICE COLOR, AND SOLUBLE SOLIDS OF TABASCOAND OF TABASCO G IN 1969

Variety and line Fruit colora Juice colorb Soluble solidsPct.

Tabasco 69-13 Blood Red Capsicum Red 12.0No. 820 No. 715/2

Tabasco G--------- 69-3 Currant Red Dutch Vermilion 10.6No. 821 No. 717/1

Tabasco G--------- 69-11 Currant Red Dutch Vermilion 10.0No. 821 No. 717/1

a,b Colors are from the British Horticultural Color Chart. The fruit and juice colors ofTabasco were a considerably lighter red than those of Tabasco G.

tinue to fruit until killed by frost in latefall.

Fruit and Juice Color. Immature fruitsof Tabasco G are a brighter yellow thanthose of Tabasco. This should im-prove the appearance of the whole-pack product known as vinegar sauce.Ripe fruit of Tabasco G are dark redand glossy as if waxed. They rangein color from Currant Red No. 821 toCardinal Red No. 822 in the BritishHorticultural Color Chart (6). Fruit ofTabasco lack this high gloss. Theircolor matches Blood Red No. 820, aconsiderably lighter shade of red, Ta-ble 3.

The juice colors of both varieties wereof a lighter tone than the external fruitcolors, but corresponded to the latter intheir relative intensity. Juice of TabascoG matched Dutch Vermilion No. 717/1

and Tabasco juice Capsicum Red No.715/2, Table 3. Lease found that Ta-basco G fruits had 39 per cent more ex-tractable red pigments (capsanthin, cap-sorubin, and zeaxanthin) than did Ta-basco fruits. Colorimetric values deter-mined by Van Blaricom confirmed thedarker red color of Tabasco G fruits,Table 4.

Percentage Dry Matter and JuiceYield. In the immature yellow-greenstage fruits of Tabasco and of TabascoG are firm and fibrous when crushed be-tween the fingers, yielding little juice.However, as the fruit matures it gradu-ally turns into a bag of juice. It is thisproperty that makes Tabasco so uniquelysuitable for hot sauce. Paradoxically theyellow-green fruit have a lower drymatter content than red ripe fruit, whileorange fruit are intermediate in this re-

TABLE 4. MATURE FRUIT COLOR OF TABASCO AND TABASCO G

Colorimetric values with Gardner color difference meter1

Variety and year RI a b a/b Color2

No.Tabasco 1967 8.03 46.7 15.5 2.69 Blood red 820

1969 9.30 34.7 19.3 1.80 Blood red 820Tabasco G 1967 4.63 36.8 12.6 2.91 Cardinal red 822

1969 8.00 38.2 17.5 2.18 Cardinal red 8221969 6.80 39.3 16.8 2.34 Cardinal red 822

' Color of fresh pepper, measured by a Gardner color difference meter with the followingstandard plate values: RI - 7.9; 'a' - 61.0; 'b' 20.4.

RI indicates luminous reflectance. A lower reflectance index indicates a deeper, moreintense color. Higher 'a' values indicate more redness. Higher 'b' values indicate moreyellowness. A higher a/b ratio indicates a more attractive red color.

2 Color names and numbers are from the British Horticultural Color Chart pp. 166, 168.Cardinal Red is a darker red color than Blood Red.

SComparisons should be by years.[7]

TABLE 5. PERCENTAGE DRY MATTER OF BULK SAMPLES OF TABASCO AND TABASCO GFRUITS AT 3 STAGES OF MATURITY

Fruit colorDry matter DifferenceTabasco Tabasco G

Pct. Pct. Pct.Dried in forced air oven at 52 C-Auburn '67

Red 31.0 22.9 26.0Orange ---------------- ---- 27.3 21.0 23.1Yellow-green 18.9 17.8 5.6

Dried in vacuum oven at 69 C-Auburn '67Red 28.9 21.3 26.3Orange----------------------- 27.9 21.3 23.7Yellow-green 20.9 16.4 21.5

Dried in vacuum oven at 52 C-Clemson '67Red 34.4 23.5 31.7

spect. The water in the immature fruitappears to be physically bound whereasit is relatively free in the mature fruit.Mature fruit of Tabasco G had 26 percent less dry matter than those of Ta-basco, Table 5. The expected increasein juice yield from Tabasco G was not,however, realized in Sims' tests. Thiswas probably because of the inabilityof the Carver press to extract as muchjuice as anticipated at the pressures used.This can be seen by the difference ob-tained when two pressures were used.For example, at 10,000 psi the juice yieldfrom Tabasco was 58.5 per cent of thefresh fruit weight, whereas it was only23.8 per cent at 5,000 psi. Neverthe-less, the highest juice yield, 55 per cent,was from a Tabasco G sample, Table 6.

Soluble Solids and Pungency. In 1968,soluble solids measurements were madewith a hand refractometer on the juiceof 30 individual ripe fruits of Tabascoand on 42 fruits of Tabasco G. Themean soluble solids of both varieties was10.5 per cent, Table 6. In 1969, twobulk samples of Tabasco G had 10.6per cent and 10.0 per cent soluble solids,respectively, and one bulk sample ofTabasco, 12.0 per cent. The differencein soluble solids between the two varie-ties probably has little practical sig-nificance, but the higher pungency ofTabasco G fruit shown in both the 1967and 1969 tests by Martin, Table 6, hasobvious economic importance for a hotsauce manufacturer (14,16).

TABLE 6. JUICE YIELD, SOLUBLE SOLIDS, AND PUNGENCY OF TABASCO AND TABASCO G FUITS

Variety Fruit Juice yielda Soluble PungencybVariety maturity 1967 1969 solids 1967 1969

Pct. Pct. Pct.Tabasco Red 23.8 53.5 10.5 7.5 7

Orange 26.6Yellow-green 26.7

Tabasco G -- ............. Red 44.0 8Red 23.8 55.0 10.5 9.0 8

Orange 26.2Yellow-green 22.7

a A Carver laboratory press was used. In 1967, samples of 73.5 g were pressed at 5,000psi. In 1969, samples of 100.0 g were pressed at 10,000 psi.

b Chemical color test by Ting and Barron's methods. The color scale ranges from 1mildest to 10 = hottest.

[8]

Seed Weights. Seed weights of twoTabasco G lines were compared withthose of two Tabasco strains. One ofthe latter was small fruited, the otherlarge. Five 200-seed samples of eachwere weighed and the mean weight of100 seeds of each calculated. The twoTabasco G seed lots weighed 0.7720 and0.7760 g/100 seeds, respectively, aver-aging 58,603 seeds/lb. The Tabascoseeds were significantly heavier, weigh-ing 0.8880 g and 0.9030 g/100 seeds forthe smaller and larger fruited strain, re-spectively, and averaging 50,602 seeds/lb. Fruit size in Tabasco was thus in-dependent of seed weight.

DISCUSSION

TEV Resistance. To maintain theTEV resistance of Tabasco G, this va-riety must be grown in isolation fromthe commercial Tabasco, as any out-crosses with the latter will be as highlysusceptible to the "etch" wilt diseaseas Tabasco itself. Tabasco G breedstrue for resistance to the disease. Fieldtrials and controlled inoculation withTEV over the past 20 years have dem-onstrated the stability of this resistance.The fear of a virus buildup in the newvariety that could threaten other moresusceptible pepper varieties in the fieldhas proved unfounded. Because Ta-basco G has a lower rate of TEV multi-plication in its tissues than do susceptiblepepper varieties that respond to infec-tion with the typical leaf mottling symp-tom (2), there would actually be lessvirus buildup in it. Furthermore, TEVis not seed transmitted. In the field mostTabasco G plants are vigorous and ap-pear to be healthy and free from TEVmottling symptoms. The development inthe field of heavily TEV inoculatedseedling transplants into bushes bearingsatisfactory crops supports this infer-ence. The evidence is that the TEVresistance of Tabasco G is permanentand horizontal as defined by Van derPlank (17).

Ripe Rot Resistance. Ripe fruits of Ta-

basco are subject to a fruit rot thatfirst shows as an orange discoloration onthe red fruit, resembling sunscald, seefigure. The causal organisms have notbeen identified. The fruit eventuallyshrivels into a dry shell varying from astraw color to a very dark red. Infectedfruits could spoil the pepper mash, orin any case reduce its quality. TabascoG derives its considerable resistance toripe rot from its two C. chinense parentsshown in figure.

Higher Pungency of Tabasco G. Thehigher pungency of Tabasco G fruits vs.Tabasco fruits was a bonus of inter-specific hybridization. This result wasmost unexpected because the Tabascovariety itself was already known to beone of the most pungent of peppers andbecause the pungency of the two C.chinense parent cultivars was an unknownquantity.

and in plant type is moderate, but nogreater than is commercially acceptableand genetically desirable to maintain thevigor and broad adaptability of the newvariety.

LITERATURE CITED

(1) GREENLEAF, W. H. 1953. Effectsof Tobacco-Etch Virus on Peppers(Capsicum sp.). Phytopathology43:564-570.

(2) GREENLEAF, W. H. 1956. Inheri-tance of Resistance to Tobacco-EtchVirus in Capsicum frutescens andin Capsicum annuum. Phytopatho-logy 46:371-375.

(3) GREENLEAF, W. H. 1967. A WiltDisease of Tabasco Pepper Causedby Tobacco-Etch Virus. ExerciseNo. 90, pp. 128-129. In A. Kelman(ed.) Sourcebook of LaboratoryExercises in Plant Pathology. W. H.Freeman and Co., San Franciscoand London.

(4) HOLMES, F. O. 1942. QuantitativeMeasurements of a Strain of Tobac-

[9]

co-Etch Virus. Phytopathology 32:1058-1067.

(5) HOLMES, F O. 1948. The Filter-able Viruses. Supplement No. 2,Bergey's Manual of DeterminativeBacteriology, 6th ed. pp. 1127-1286plus Index. The Williams andWilkins Co., Baltimore, Md.

(6) Horticultural Color Chart Issued bythe British Colour Council in Col-laboration with the Royal Horti-cultural Society. Copyright - Rob-ert F. Wilson, 1938. Printed inGreat Britain by Henry Stone andSon Ltd., Banbury.

(7) McIlhenny Company. 1958. Ta-basco, its Romantic History, itsWonderful Way with Foods and75 Recipes from the Famous Ta-basco Collection. Pamphlet, Copy-right - Mcllhenny Company, AveryIsland, La.

(8) Mcllhenny Company. 1968. The100 Year History of Tabasco and10 Recipes that Helped Make itFamous. Commemorative Bro-chure, Copyright - McIlhennyCompany, Avery Island, La.

(9) MEAD, C. R. 1962. Hot PepperHaven. The Furrow, November-December, pp. 2-3.

(10) SHALETT, SIDNEY. 1956. Hot Pep-per Island. Sat. Eve. Post 228:43,59,60,62.

(11) SMITH, PAUL G. 1951. DeciduousRipe Fruit Character in Peppers.Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 47:343-344.

(12) SMITH, PAUL G. AND CHARLES B.HEISER, JR. 1951. Taxonomic andGenetic Studies on the CultivatedPeppers Capsicum annuam and C.frutescens. Amer. Jour. Bot. 38:362-368.

(13) SMITH, PAUL G. AND CHARLES B.HEISER, JR. 1957. Breeding Be-havior of Cultivated Peppers. Proc.Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 70:286-290.

(14) TING, S. V. AND KEITH C. BARRONS.

1942. A Chemical Test for Pun-gency in Peppers. Proc. Amer. Soc.Hort. Sci. 40:504-508.

(15) TRAPPEY, B. F. AND SONS, INC. TheSecret of Creole Cooking. Un-dated Pamphlet, New Iberia, La.

(16) VAN BLARICOM, L. O. AND J. A.

MARTIN. 1947. Permanent Stand-ards for Chemical Test for Pun-gency in Peppers. Proc. Amer. Soc.Hort. Sci. 50:297.

(17) VAN DER PLANK, J. E. 1968. Dis-ease Resistance in Plants. AcademicPress, Inc., New York.

[10 ]