“Blue-ice”: framing climate change and reframing climate ... · framing climate change and...

Transcript of “Blue-ice”: framing climate change and reframing climate ... · framing climate change and...

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found athttp://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tcld20

Climate and Development

ISSN: 1756-5529 (Print) 1756-5537 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tcld20

“Blue-ice”: framing climate change and reframingclimate change adaptation from the indigenouspeoples' perspective in the northern boreal forestof Ontario, Canada

Denise M. Golden, Carol Audet & M. A. (Peggy) Smith

To cite this article: Denise M. Golden, Carol Audet & M. A. (Peggy) Smith (2015) “Blue-ice”:framing climate change and reframing climate change adaptation from the indigenous peoples'perspective in the northern boreal forest of Ontario, Canada, Climate and Development, 7:5,401-413, DOI: 10.1080/17565529.2014.966048

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2014.966048

Published online: 05 Nov 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 475

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Citing articles: 1 View citing articles

RESEARCH ARTICLE

“Blue-ice”: framing climate change and reframing climate change adaptation from the indigenouspeoples’ perspective in the northern boreal forest of Ontario, Canada

Denise M. Goldena*, Carol Audetb and M. A. (Peggy) Smitha

aFaculty of Natural Resource Management, Lakehead University, 955 Oliver Road, Thunder Bay, ON, Canada P7B 5E1; bNishnawbe AskiNation (NAN), Unit 200, 100 Back Street, Thunder Bay, ON, Canada P7 J 1L2

(Received 7 January 2014; final version received 7 July 2014)

The northern boreal forest in Ontario, Canada, in the sub-Arctic above the 51st parallel, is the territorial homeland of the Cree,Ojibwe, and Ojicree Nations. These Nations are represented by the political organization Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN).January 6–March 31, 2011 the researchers and NAN collaborated in a study to record observations of changes in theforest environment attributed to climate change and share and exchange information and perspectives about climatechange. Data were collected from 10 First Nation communities across a geographic area of ∼110,800 km2 (43,000 mi2).We explore climate change impacts through the lens of “blue-ice”, a term embedded in their languages across thefieldwork area and reframe adaptation in the First Nations’ perspective and worldview. Changes in blue-ice on thelandscape are affecting transportation in traditional activities such as hunting and fishing, as well as the delivery ofessential community supplies. The word “adaptation” linked to climate change does not exist in their languages and theterm is associated with European colonization. We propose the term “continuity” to reflect the First Nation worldview.Our recommendation is giving First Nations’ perspectives and knowledge of their territorial landscape a foundational rolein the development of climate change policy for Ontario’s northern boreal forest.

Keywords: adaptation; climate change; cultural continuity; energy security; First Nations; food security; participatory actionresearch; sub-Arctic; traditional activities; worldviews

Introduction

The indigenous peoples1 of the boreal forest north of the51st parallel in Ontario, Canada, are Cree, Ojibwe, andOjicree people who reside in 32 First Nation communities.First Nations are recognized within Canada as “Aboriginalpeoples” having Aboriginal and treaty rights, affirmed bySection 35 of Canada’s Constitution Act, 1982. These 32northern communities, as well as an additional 17 others,are represented by Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN), a Pro-vincial-Territorial Organization. Their homeland coverstwo-thirds of the province of Ontario, spanning approxi-mately 544,000 km2 (∼210,000 mi2) (NAN, 2011).

In 2010, Ontario passed the Far North Act. The Actenables land use planning for resource development (e.g.mining and hydroelectricity) and includes the goal of50% protection of the land base to support biological diver-sity and maintain ecological processes and functions,“including the storage and sequestration of carbon fromthe atmosphere” (OMNR, 2011). The land area coveredby the Act (∼450,000 km2 or ∼174,000 mi2) is landwithin the traditional territory of NAN member FirstNations. While First Nation involvement and approval of

land use plans are enabled by the Act, NAN raised strongobjections to the legislation,2 stating that as worded theAct gives the Minister (in the Ministry of NaturalResources overseeing the Act) the final decision-makingauthority, and as such impedes their rights to decide how,where, and when their lands and natural resources wouldbe developed or conserved.

Policy decisions to address climate that affect NANFirst Nations and are made without their full engagementand input will fail to fully consider their rights, perspec-tives, or values. First Nations within NAN have directties to the land and recognize the importance of addressingclimate change impacts in their territories. The rapidlyoccurring changes related to climate change are influencinghow they interact with, and respond to, a changing environ-ment. Threats from floods and forest fires, and changes onthe land are affecting community safety, food, and energysecurity.

In 2010, NAN and the researchers (hereafter referred toas the research team) developed a research proposal andentered into a research contract defining each party’sroles and responsibilities. The objectives of the research

© 2014 Taylor & Francis

*Corresponding author. Email: [email protected]

Climate and Development, 2015Vol. 7, No. 5, 401–413, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2014.966048

included: (i) documenting community members’ obser-vations of climate-related changes occurring in the forest,(ii) examining First Nation perspectives and engagementin policy development on climate change, and (iii) examin-ing the potential for northern boreal forests to mitigateclimate change. This paper presents the first objectivewith discussion of First Nation observations in changes tothe forest environment, and one aspect in the second objec-tive – their perspectives on adaptation related to theirworldview and relevance in climate change policy.

We begin our discussion with the concepts of adap-tation, resilience, adaptive capacity, and the growing litera-ture on joint scientific and indigenous knowledge researchin climate change. Presented in the discussion is an over-view of the research method – Participatory ActionResearch (PAR) and combining scientific and indigenouspeoples’ worldviews. We continue with a brief descriptionof the geography of the study area and the homeland of theFirst Nations collaborating in the research. Next, we presentfieldwork observations from the First Nation participantson the rapidly occurring and unpredictable changing con-ditions on their land through the lens of “blue-ice”.

Blue-ice is more than “ice”. “Blue-ice” is a termembedded in their indigenous languages. It refers to aspecific environmental condition in its formation that isboth a familiar frame of reference in seasonal cycles andin activities carried out on the land, and constant in itsimportance as an element of life. Our analysis on the disap-pearance of blue-ice observed by First Nations is an indi-cator of warming temperatures on the planet (see Mueller& Vincent, 2003; NASA, n.d.), and is significant to thesepeople affected by its disappearance. Changes in blue-iceare a climate change impact on transportation, whichaffects food security, energy security, and traditional activi-ties. Discussion includes participants’ responses to the term“adaptation” based on their worldview and historicalcontext. We propose the word “continuity” to reflect theFirst Nation view of adapting to the landscape – aprocess that has been perpetual over millennia (notrestricted only to more recent anthropogenic climaticchanges). We recommend giving First Nations perspectivesand ecological knowledge of their changing landscape afoundational role in the development of climate changepolicy for Ontario’s northern boreal forest.

Adaptation, climate change, and indigenous peoples

Impacts from climate change will not be distributed equallyaround the world (Fischlin et al., 2007) and attention is nowshifting from climate change mitigation to climate changeadaptation3 (Folke, Pritchard, Berkes, Colding, & Svedin,2007; Huntjens et al., 2012). Mitigation efforts towardsclimate change intend to reduce the severity of impacts,while adaptation assumes there will be significantchanges and therefore adjustments will be required in

activities, thinking, and decision-making (Kwiatkowski,2011). Adaptation in relation to climate change hasseveral definitions and related concepts found in the aca-demic and grey literature (Levina & Tirpak, 2006). Differ-ent interpretations and definitions of the term have beenadopted by different fields, such as anthropology,biology, and business management, and the more recentsocial development and justice arenas, to align with theirparticular disciplinary foci (Engle, 2011; Walker, Holling,Carpenter, & Kinzig, 2004).

The shift in focus to address climate change from miti-gation to adaptation is reflected in, and connects, twoschools of thought – socio-economic development andsocial-ecological interactions. The sustainability andsocio-economic development literature discusses vulner-ability and risk (Walker et al., 2004), with a focus on chan-ging human activities to prevent or mitigate climate change(Engle, 2011). In the social-ecological system literature,adaption discussions centre on the attributes of a system’sresilience, adaptability, and transformation (Walker et al.,2004). Since Holling’s (1973) seminal paper on theconcept of resilience, refinements of the concept haveemerged (Walker et al., 2004). Holling’s concept was tounderstand the capacity of ecosystems to persist in the orig-inal state subject to “perturbations” (Folke et al., 2010), orsimply put, to understand ecosystem responses to change(Adger et al., 2011). Since then concepts from the resilienceand vulnerability literature have been applied with sustain-able development concepts (Park et al., 2012) to understandthe complex systems of human responses to environmentalchange, particularly adaptation to climate change (Abel,Cumming, & Anderies, 2006; Huntjens et al., 2012; Parket al., 2012). O’Brien, Hayward, and Berkes (2009) arguethat resilience research into the interaction of social andecological subsystems provides insight into complexsystems as a whole. Untangling the complexities todevelop effective policies is viewed as essential to sustain-ability for ecological and socio-economic systems (Liuet al., 2007).

Folke et al. (2007) suggest ecological and humandimensions “are not just linked but truly integrated ... andthe interplay takes place across temporal and spatialscales and institutional and organizational levels insystems that are increasingly being interpreted ascomplex adaptive systems”. Complex adaptive systems(CASs) theory builds upon and differs from traditionalsystems theory in that it incorporates the role of adaptationin the dynamics and responses of complex systems. CASsare characterized as self-organizing, a complex whole inter-acting at a localized scale in non-linear dynamics, andacross temporal and spatial scales (Hartvigsen, Kinzig, &Peterson, 1998). The key element is the influence of adap-tation. There are three fundamental characteristics in theability to adapt that contribute to the overall resilience ofa system: (1) a system’s susceptibility to change while

402 D.M. Golden et al.

still retaining its structure and function, (2) the degree asystem is capable of self-organizing, and (3) adaptivecapacity to learn and adapt (Abel et al., 2006; Carpenter,Walker, Anderies, & Abel, 2001).

Vulnerability is the degree to which a system is likely toexperience harm, as in the extent and occurrence of a dis-turbance from internal and external variables, which canbe from global, regional, and local forces (Liu et al.,2007). Defined by Walker et al. (2004), resilience is theease or difficulty of changing a system – that is, how resist-ant it is to change due to a disturbance, and its ability toretain essentially the same function, structure, identity,and feedback during change. The concept of adaptivecapacity has emerged from the sustainability (focused onvulnerability) and social-ecological (focused on resilience)literature. A key element of adaptive capacity is its creationfrom the production and communication of information andknowledge (Lemos, Boyd, Tompkins, Osbahr, & Liver-man, 2007).

Indigenous knowledge, often referred to as TraditionalEcological Knowledge (TEK), has led to the developmentof elaborate coping strategies and valuable knowledgethat plays a role in adaptation to and mitigation ofclimate change (Macchi et al., 2008). Indigenous knowl-edge is a cumulative body of knowledge and beliefs, evol-ving by adaptive processes and handed down throughgenerations (Davidson-Hunt & Berkes, 2003). Studies onthe knowledge of indigenous peoples in adapting to andmitigating climate change (Devkota, Bajracharya, Mara-seni, Cockfied, & Upashyak, 2011; Macchi et al., 2008),the adaptive capacities of indigenous peoples to climatechange (Galloway McLean, Ramos-Castillo, & Rubis,2011), and the co-production of knowledge on climatechange (Berkes, 2009) have brought indigenous perspec-tives on adaptation and the application of traditional knowl-edge to modern climate change problems (Berkes, Colding,& Folke, 2000; Galloway McLean et al., 2011). As directusers of the natural environment, indigenous peopleshave valuable and experiential knowledge at a regionallevel on ecosystems and the services they provide (seeDavidson et al., 2014). Adger et al. (2011) argue manysources of resilience in the collections of social and insti-tutional memories (i.e. past experiences and successfuladaptions to change) are likely to be challenged byclimate change and are insufficient in managing resilienceunless put to use – at different scales in scope, time hor-izons, and governance (including regionalizing influenceand authority) to frame problems and recombine experi-ences in order to build adaptive capacity.

In Canada, research with indigenous peoples on climatechange has largely focused on the Arctic (Cobb, Kisalioglu,& Berkes, 2005; Cruikshank, 2001; Dowsley, 2009; Henry,Meakin, & Mustonen, 2013; Huntington, Callaghan, Fox, &Krupnik, 2004; Nakashima, 1993; Pearce et al., 2009). Ourdiscussion of adaptation reflects a conversation that brings to

light perspectives from indigenous peoples in 10 commu-nities living across the sub-Arctic in the boreal forest.

Study overview

Research method and data collection

The study is a collaboration between NAN (as an umbrellaorganization and participating communities), the academicresearchers, and individual participants, using PAR. Tra-ditional knowledge is “usually described by Aboriginalpeoples as holistic, involving body, mind, feelings, andspirit” (TCPS-2 Sect. A., 2010). In western science, therestill exists a mindset that it is superior to TEK (Pretty,2011) in that knowledge that includes “feelings and spirit”or “anecdotal” information cannot be measured or quanti-fied, and is therefore not scientific. Moreover, perspectivesfrom oral traditions have too often been utilized as data inscience rather than stand-alone knowledge or theory (Cruik-shank, 2001). However, there is an increasing recognitionthat local and indigenous knowledge, particularly in areasof high environmental priority such as climate change,may provide insight and fill in data gaps on remote orhard-to-access environments (Brook & McLachlan, 2008).Incorporating the depth and breadth of TEK on the historicand current status of the land (e.g. biophysical conditions,flora, and fauna) across large geographic areas of traditionalterritory is invaluable to fill gaps in scientific knowledge andin forming appropriate policies in rapidly changing environ-ments (Dowsley, 2009). Studies have discovered drawing onindigenous knowledge produces a better understanding thanwestern knowledge and scientific methods alone, despite thechallenges with integrating the two knowledge systems(Bohensky & Maru, 2011; Cochran et al., 2008). Moreover,growing literature from indigenous scholars places localexperiences in a broader context and is therefore relevantas a knowledge paradigm parallel with western knowledge(Henry et al., 2013).

This study incorporated the main characteristics ofPAR: (i) educative (for both parties), (ii) dealing with indi-viduals as members of a social group, (iii) problem-focusedwith the intent of taking action, (iv) treating all participantsas inherently part of the process, and (v) a collaborationwhere each party contributes and each party benefits fromthe interaction (Winter & Munn-Giddings, 2001). PARcreated the pathway for two-way knowledge exchanges:building capacity on climate change at the communitylevel (i.e. forest science, climate change science, and politi-cal dialogue) identified at the onset to be a part of and astrength of the research, and recording observations fromcommunity members living in the sub-Arctic borealforest environment related to climate change.

Our discussion is a collection of responses conductedwith careful, systematic audio-recordings during semi-structured interviews with individuals and focus groups,

Climate and Development 403

along with field notes and memoing. Forty-three individ-uals from the visited communities contributed to theresearch data.4 The vast majority of the contributors werekey informants or knowledgeable people within a commu-nity. Huntington (2000) argues that having a communityidentify and introduce key persons to a researcher is thedesired approach to reach individuals having the knowl-edge and information relevant or useful to the research. Afew participants the principal researcher met whilewalking or shopping in a community (“random” partici-pants). The participants represent Council members,Elders, Land Users (hunters, trappers, fishers, and gath-erers), community land use planning members, winterroad staff, and other community members. For thepurpose of our discussion, descriptions for the role of acommunity member are found in Table 1. The informationprovided by these individuals was coded for themes andorganized using QSR NVivo 9 software.

Elders represent the largest community group inter-viewed (30%), Winter road staff made up 16% of the par-ticipants, Land use planning members represented 12%,and seasonal/traditional land users 8% of the participants.It should be noted winter road staff, land use planningmembers, and other community members are usually also“land users”, but their specific role in the communityrelated to their employment is very relevant in the discus-sion of “blue-ice” and therefore noted accordingly.

Research area

From January 6 to March 31, 2011, 10 First Nation com-munities located in northern Ontario, Canada, at latitudesbetween 51° and 54°N, from near the Manitoba border inthe west to the James Bay coast in the east, a geographic

area of approximately 110,800 km2 (43,000 mi2), partici-pated in the research (Figure 1). The communities contri-buting to the data, in order of visits were: Muskrat Dam,Weagamow, Pikangikum, Sandy Lake, Neskantaga, Nibi-namik, Attawapiskat, Fort Albany, Kingfisher Lake, andWunnumin Lake. These communities are in very remotelocations only accessible by aircraft with the exceptionof travel during winter months on winter/ice roads, andfor the two communities along the James Bay coast (Atta-wapiskat and Fort Albany) short-time river barge trans-portation in the summer. These First Nations areintrinsically connected to the climate, landscape, flora,and fauna. Hunting, fishing, and trapping (e.g. moose(Alces alces), walleye (Sander vitreus), and marten(Martes americana)) are part of their culture in traditionalactivities and family gatherings (e.g. seasonal hunts ofsnow goose (Chen caerulescens)), as is gathering fire-wood and wild fruits such as the blueberry (Vacciniummyrtillus).

The study area contains two ecozones: the BorealShield, Canada’s largest ecozone, and the Hudson Plain(or Lowlands).5 Advancing and retreating glaciers etchedthe depressions and shaped the regional landforms creatingthe thousands of lakes, numerous rivers and streams, vastwetlands, and peatbogs (muskeg). Land elevations(within the study area) vary from 360 m in the west tosea level in the east.6 The area, as classified by Köppen,7

has a continental sub-Arctic or boreal climate. The sub-Arctic region experiences the most extreme seasonal temp-erature variations found on the planet, ranging from −40°C(−40°F) in winter to +30°C (86°F) in the summer.Historically, summers are short lasting no more than threemonths and winters are severe lasting five to sevenmonths with snowstorms, strong winds, and bitter cold

Table 1. Community roles of interviewees.

Community role Description

Council member An elected individual by the First Nation community – these individuals can be the Chief, DeputyChief, or Band Council member

Elder An individual recognized in the community for their generational knowledge; not necessarilysomeone who has lived a long time, though usually (i.e. a grandparent or retired person); acommunity advisor and a traditional teacher; lives or has lived a traditional lifestyle

Traditional lifestyle land user An individual who lives off the land using traditional activities – hunting, fishing, trapping, gatheringfuel, and plants (edible and/or medicinal); makes tools and equipment (e.g. snowshoes, nets, andbowls)

Seasonal land user An individual who engages in traditional activities on the land either on weekends (e.g. fishing),when hunting seasons occurs for various species of animals/birds (e.g. moose and goose) orgathering edible and medicinal plants when in season (e.g. blueberries). Seasonal land users areusually employed within the community (e.g. schools, nursing stations, band offices, and airports),employed in an industry near the community, volunteer, or have other roles in the community

Community land use planningteam member

An individual employed by the community to create a land use plan around a community’s reserveland identifying potential development areas (e.g. forestry and mining), traditional and sacredplaces (e.g. trap lines and burial sites), and ecologically important sites (e.g. wetlands andwaterways)

Winter road staff An individual employed by the community to build and maintain the roads during winter roadseasons

404 D.M. Golden et al.

due to continental polar and Arctic air masses. Precipitationoccurs throughout the year in the forms of rain and snow.

Results and discussion

“Blue-ice”: a lens into climate change

Evidence for climate change and its effects on the lives ofmillions of indigenous peoples8 is accumulating in the lit-erature (Downing & Cuerrier, 2011; Galloway McLean

et al., 2011). The changes demonstrate a deviation fromfamiliar conditions outside a culture’s traditional knowl-edge (Sakakibara, 2011). During the course of the field-work, similar findings arose in the repeated descriptionsof changes in seasonal temperatures and precipitation, veg-etation and wildlife, along with comments on the rapid rateand extent of changes observed and experienced, the uncer-tainty as to why these events were occurring, and the unpre-dictability of environmental conditions on the landscape.Crate (2008, p. 527) points out that “in the field, we need

Figure 1. Fieldwork map: Indicated are the northern communities visited and travel hub centres from which travel to the communities waspossible. Flights north originate below the 50th parallel in Sioux Lookout (in the west) and Timmins (in the east); travel in east–west direc-tions to access the northward hubs requires stops in Thunder Bay, Sault Ste. Marie, and Sudbury, ON. Total travel distance to reach thecommunities was nearly 6300 km (3900 mi). In our discussion, we divide the study area into three regions N of the 51st: the west, at longi-tudes between 91° and 94°W, central, at longitudes between 87° and 90°W, and the east, at longitudes between 81° and 83°W.

Climate and Development 405

to understand how our research partners frame the localeffects of global climate change in order to tease out cul-tural implications”.

The reference to kah-oh-shah-whah-skoh-siig mii-koom as pronounced in Ojicree, and written in Ojicree syl-labics as , or “blue-ice”, was a phrase consist-ently used by First Nations to describe a specific andfamiliar environmental condition that is rapidly changing,with significant implications and relevance to communitymembers across the study area. The importance of “blue-ice” formation on lakes and rivers (and in general frozenwaterbodies and the muskeg) cannot be understated withrespect to First Nation recollections and memories, its cul-tural significance in traditional activities, and the currentand future well-being of these communities. The formationand presence of ice influence these First Nation commu-nities throughout the year. Tremblay et al. (2006) hadsimilar findings in their study using traditional knowledgeand local observations as well as scientific knowledge tocharacterize ice conditions relevant to the Aboriginal com-munities involved. “Blue-ice”, though noting a colour (andis blue-greenishwhere fresh water meetsmarine water in themouth of the rivers at James Bay9), is a cultural and commu-nity frame of reference to the conditions and attributes of theland, and the activities connected to them. It is fixed in thepast, present, and future and climate change observed bythese First Nations is discussed through that lens.

Blue-ice in the scientific literature has specific proper-ties and particular meteorological circumstances in its for-mation (see Yu, Liu, Jezek, & Heo, 2012 on blue-ice inthe Antarctic). In the northern boreal, “blue-ice” formsout of water exposed to very cold sub-zero temperaturesover an extended period of several weeks.10 Explained byGudra and Najwer (2011), “supercooled water and lowair temperature are ideal conditions for the formation offrazil ice, small crystals of free-floating ice” (p. 625).Though this may seem to be straightforward, the timingof two environmental conditions must be met in theforming of “blue-ice” – frigid temperatures and theabsence of snow. As explained by an Elder, the arrival ofsnow on open water is beneficial, to quickly chill thewater, but not beneficial after the initial ice forms:

When I was a kid… from September to October it used tobe cold, really cold…when the lake started to freeze andwe used to have blue-ice and this blue-ice lasted like along time before the snow comes ... and when the snowcame we didn’t have a snow that was coming down likea slush, because it was so cold. But now every winter,the snow usually comes first. We have snow on theground first and then we would have slush on the lakesand then ... it freezes up. (Elder, central region)

When snow arrives too soon after the initial layer of iceforms, water underneath the ice is insulated from the coldnorthern air impeding “blue-ice” formation. Snow also hasother influences on ice formation. As explained by a commu-nity member, during ice formation water naturally floodsacross the ice surface from open areas or at ice edges, andwhen water meets snow the formation of slush occurs (aslurry mixture of snow crystals and liquid water). Snow onthe ice surface can also cause melting of the existing icecreating a contact zone of water and snow that results inslush. Slush when it freezes is a white-coloured ice, andreferred to as “slush” by First Nations even in frozen form(due to its mixture of snow and water and not solelywater). Differences in the types of snow are also a factorin ice formation and falling snow is mostly affected by temp-erature (Table 2). In the scientific literature,

there are various types of ice, differentiated depending onthe way it is formed. Snow ice forms when snow falls onwater surfaces at a temperature of about 0°C [32°F] – icedoes not melt. Sudden temperature drop causes snow iceto change into white ice. (Gudra & Najwer, 2011, p. 625)

The major difference in blue-ice and slush is strength.Recorded from interviews in the study area, “blue-ice isthe strong ice that freezes right” (Elder, west region)when “the cold was strong” (Elder, central region). Ice isdiverse by nature and blue-ice is dense (in comparison toslush) and considered twice as strong; therefore, “thereneeds to be twice as much slush ice to equal the strengthof blue-ice” (Winter Road staff member, west region). Inthe scientific literature, there are no established methodsfor measuring ice parameters; the most common examin-ation of ice is measuring layer thickness in a water body

Table 2. Air temperature and snow crystal formation. Adapted from Gudra and Najwer (2011) and participant snow descriptions.

Air temperatureSnow crystal

type Snow crystal characteristics

Below −10°C (14°F) Powder snow Fluffy, light weight, small in size like dust particles; non-sticking separate crystals;easily moved by the wind; and dissolves quickly in open water

Between −10°C and −3°C(14°F and 27°F)

Packed snow Heavier than powder snow; crystals will eventually stick together, forming a dense layeror compacted snow layer on the land; packed snow can be walked on leaving nofootprints

Above −3°C (27°F) Wet snow Heavy snow due to its water content; crystals easily merge together forming a group offlakes or clumps; crystals stick well together creating a water-snow mixture; can bethe consistency of sloppy “mashed potatoes” and difficult to travel across

406 D.M. Golden et al.

(Gudra & Najwer, 2011). The depth of blue-ice describedrepeatedly across the study area was nearly half the depth(or even less) as in the past.

Along with changes in the formation and depth of blue-ice is the duration of ice on the land from its arrival tobreakup. In the past, ice began to form in the fall (Septem-ber/October) and remained until May (or even into June);its presence on the land lasting six to eight months. Inrecent years, blue-ice (slush and ice in general) isforming later and disappearing earlier, by nearly twomonths and even more. Community members rememberthose conditions in these translations:

On the river systems… on the shores of the rivers ... wewere still dragging our boats. A long time ago… thelakes and the river system around June 10 would be thetime that they would open up. (Elder, central region)Now the ice is gone when it is maybe March. (TraditionalLifestyle Land User, central region)For breaking, for the ice to break, sometimes it happens inApril but usually that is in May ... the beginning of May…it happens in the past they say in June ... the ice broke.(Winter Road Maker, east region)

First Nation knowledge on ice formation, strength,thickness, timing, and duration is widespread across thenorthern boreal because the presence of ice is a criticalfactor in the activities carried out on the land. FirstNations are witnessing changes in both snow (the timing

and type) and warmer temperatures in the monthsin which blue-ice historically formed and stayed on theland.

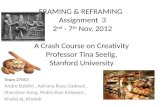

Impacts from changes in Blue-ice

For these First Nations, the significance of disappearingblue-ice is the transportation link to food and energy secur-ity, and continuity with traditional activities. Winter roadaccess is a vital lifeline in these remote communities as itis the only time in which the economical transportation ofgoods and supplies occurs. Each community is responsiblefor building a section of the winter road system to createtransportation corridors from the north to access permanenthighways and urban centres south of the 50th parallel.Transported goods include groceries, and in some casespotable water, fuel (gasoline and diesel), modular housesand building supplies, household items (furniture, appli-ances, computers), equipment and tools (school, medical,electricity generators), and vehicles (cars, trucks, andsnowmobiles). At many times during the fieldwork,winter roads were not open. Instances of road-makingequipment falling through the ice (Figure 2) or rivers begin-ning to flow signalled the temporary halt of transport trucksor the end of the winter road season. At times, even accessfor cars and light trucks was questionable.

Community members in charge of winter road makinghave had to adjust the type and weight of equipment to the

Figure 2. Snowplough fallen through the ice. Photo taken January 2011 between Sachigo Lake and Muskrat Dam, Ontario (west region).The absence and/or decreased depth of “blue-ice” formation are attributed to the reduction in the strength of the ice for winter road trans-portation. Source withheld; printed with permission.

Climate and Development 407

strength-bearing capacity of the ice. In the 1980s, heavysnowploughs in excess of 18 tonnes were standard equip-ment, which changed to 10 tonne equipment 10–12 yearsago, to the current use of lighter and smaller ¾ and 1tonne trucks fitted with ploughing equipment (personalcommunication, Vernon Morris).11 This adjustment reflectsa compounding dilemma with the disappearance of blue-ice. Smaller road-making equipment increases the timeneeded to complete and maintain the winter road, and thetimeline for reliable winter road conditions is becomingshorter. The following observations emphasize thechanges in winter roads across all regions in the study area:

Last winter ... there was hardly any winter. I noticed that. Itdidn’t freeze up.… and then the spring, it comes too fast.The reason why I noticed that ... was the winter road. Wecouldn’t use it after that. It was a really short winter. (Sea-sonal Land User, west region)The winter road didn’t last that long ... I think they finishedit in January [2011] and they are still good… so probablythis is the last week [last week of March] to use it. (Seaso-nal Land User, central region)Last year we were like a month behind schedule because ofall the mild days we had… couldn’t do it [make the road].(Winter Road Maker, east region)

Diminishing winter road access significantly increasesthe prices of goods and decreases availability. Withoutwinter roads, goods (though not large heavy items) arriveby costly air cargo. During the fieldwork it was not uncom-mon to pay ∼CAD 5.00 for a dozen eggs. Gasoline waspriced at CAD 2.45/litre (∼US $9.80/gallon)12 or moreduring times of scarcity, and at times shelves in the stores(particularly perishable foods) and fuel tanks at the gaspumps were exceedingly low or empty. Moreover, thefurther people travel out on the land to obtain traditionalfoods due to changes in animal and bird habitat andmigration, the more expensive it becomes to carry out tra-ditional activities for food. A community memberexplained the situation: “It is not worthwhile to go moosehunting as it is expensive… the ride is very expensive…it comes out about the same as to buy food from the storethan to go hunting.”

With fuel trucks increasingly unable to access commu-nities, not only will cost be an important factor, but also thesupply of fuel will be in jeopardy. Less fuel for vehiclesmay not be as critical as less fuel for electricity.13 NorthernNAN communities rely on diesel-generated electricity withthe exception of the few NAN communities along theJames Bay coast connected to the province’s electricalgrid. Electricity not only powers appliances, but alsoheating and cooling systems in homes, buildings(schools, nursing stations, and band offices), and the com-munity water treatment plant. While many homes are woodheated, many are not. No heat in the winter at sub-zerotemperatures is potentially life threatening. In addition,

access to potable water is an issue in every community. Itis a minor issue when an electrical generator temporarilyfails, shutting down the treatment plant and pumpingstation, but in some communities, access to potable watercan be a major issue when the water quality is so poorthat it has to be delivered whether by transport trucks orair cargo.

Some community members and Elders (still physicallycapable) live off the land in a traditional lifestyle usingskills that have been passed down to the next generationmostly through teaching by doing, but there are changesoccurring:

In the ‘70s I had the opportunity to work the land withElders, people who taught me how to trap, hunt and fishand I appreciate what is out there on the land. We learnedthe language again, and the customs, the way of thoughtand how to care for the land and for the animals andstuff.…All that is changing really fast. (CouncilMember, west region)

Many community members, though employed withinthe community (e.g. schools, band council offices, andwinter road making) and not living off the land, are still“land users” travelling across lakes and rivers to reach tra-ditional hunting, trapping, and fishing areas on weekendsand during seasonal activities (e.g. goose hunts). Landusers are acutely aware of changes in ice conditions affect-ing traditional activities particularly in terms of personalsafety. Changes in ice conditions, sometimes very unpre-dictable on a day-to-day basis, present potentially life-threatening situations:

There was this one area ... it thawed… really fast ... and itwas this area where I fell through the ice. ... It was justwhite ice too; there was no blue-ice. It was just like asnow that had frozen there, no ice. But I was all bymyself and when I first fell into the ice I got scared wonder-ing how I’m going to get out. (Winter Road Maker, westregion)We trap, and we hunt out this way, like out towards [the]east… there is a river that goes all the way to James Bay…we used to go across by dog team or our skidoos [snow-mobiles]. Now we can’t even go across them in someplaces. (Traditional Lifestyle Land User, central region)

Regardless of the changing conditions, First Nations’continuity with the land remains, though how traditionalactivities are conducted or the timing of when some activi-ties occur is changing.

Like I said, the middle-end of April we [the family] wouldgo set up and then do hunting through till the third of weekof May. ... It’s like earlier and earlier that we have to go setup because we have to carry a lot of stuff over. ... I don’twant to take it all by canoe ... when the ice is already allgone; so what we do is we go there prior, set it all up ...leave it there until we go geese hunting. But this year it

408 D.M. Golden et al.

was not even five days after we set up that we werealready back out there hunting geese because they werealready there. (Traditional Lifestyle Land User, westregion)

In every community, “blue-ice”, along with ice, slush,the unfrozen, and melting landscape, was a notable recur-rent topic of discussion in regard to observations ofchanges and activities carried out on the land.

Adaptation and reframing the language

Archaeological evidence suggests that indigenous popu-lations have previously adapted to climate change(Applied History Research Group, 2000, 2001). Recentlyrecognized are “culturally appropriate adaptations”14

devised through community participation, which arenecessary for indigenous communities to adapt to climaticchanges (Downing & Cuerrier, 2011). For researchers tounderstand the impacts and adaptations to climate changeof indigenous peoples requires a different lens. To do so,it is necessary for researchers to reframe their viewpointthrough dialogue and engagement with indigenous commu-nities (Pearce et al., 2009). The collaborative nature of thisstudy between NAN, its communities, individual partici-pants, and the research team created the space to explorethe language and context of climate change adaptationfrom a First Nation’s worldview.

NAN representatives and participants in the studyreacted to the term “adaptation”. In the Cree, Ojibwe, andOjicree languages spoken in NAN territory, the word“adaptation” does not exist. First Nations in this area,prior to European contact, lived a nomadic lifestyle forthousands of years, moving with seasonal resources in tra-ditional activities or into more favourable locations withchanging circumstances on the land and have long under-stood the need to act in accordance with the changing land-scape because their lives and livelihoods depend on it.Adaption was inherent, not a term.

In modern times, “adaptation” must be understood inthe political context between First Nations and the Cana-dian state. It is a term coloured by colonization. Canadianstate policy with First Nations has had an assimilationgoal exercised more clearly at some historical periodsthan others (Tobias, 1976). Legislation passed in 1857,the Gradual Civilization Act,15 captured this intent, as dida proposed amendment to the Indian Act (1867) in 1920,giving the federal government the power to eliminate(enfranchise) First Nations’ legal status as “Indians”(Salem-Wiseman, 1996). For First Nations, adaptationhas meant struggling against assimilation policies to main-tain their identity as peoples. While the state consolidatedits power, First Nations were forced to adapt by losingtheirs. One interviewee captured this sense of loss ofcontrol:

Adapting to change…maybe I misunderstand that becauseadapting to change is changing my thought, my view onlife… to something that is imposed on me. And I reallyhave no power to assist in that process. (Seasonal LandUser, west region)

Adger, Arnell, and Tompkins (2005) point out thatassessing the success of adaptation will involve new andchallenging institutional processes that should be judgedon the criteria of effectiveness, efficiency, equity, and legiti-macy. The last two criteria are particularly relevant to FirstNation communities. Consideration needs to be made forthe social and human rights implications of climatechange (OHCHR, 2009) including the rights to life (foodand water), along with free, prior, and informed consent(FPIC16) in the use of their territories to address climatechange and in decisions to manage and adapt to theimpacts. Dowsley (2009) argues reducing policy barriersthat constrain community level decision-making in turnincreases community options and adaptive capacity thatcan help to cope with rapidly changing environments.

Adaptation needs to be understood not only in the politi-cal context, but also more importantly, in terms of FirstNation values and beliefs about their relationship to theland. The First Nation worldview is rooted in ties to theland with responsibility given to them by the “Creator” tolook after that land (NAN, 1977). That responsibility stilldefines how First Nations see themselves, in spite ofchanges forced upon them, whether it is state policy orclimate change. Indigenous knowledge is interconnected tothe individual as part of all living things, the earth, stars,and planets (Botha, 2011; Chinn, 2007) and described as hol-istic and “different ways of knowing” (Botha, 2011; Pretty,2011). It could be argued that the interconnected indigenousperspective across temporal and spatial scales (see David-son-Hunt & Berkes, 2003) reflects the concepts of CASstheory, and perhaps this perspective has a greater scope inunderstanding a complex issue like climate change. Thiswealth of knowledge has only begun to be understood,accepted, and applied outside indigenous communities.

While adaptation necessitates change, “adjustments” toclimate change should be limited to ecological, social, andeconomic aspects (Smit & Pilifosova, 2001). First Nationsin the study recognize the need to develop anticipatoryreactions to rapid climate change and to evolve activities,but remain the same as a people. Continuity in activitieson the land occurs as noted from this interview:

I pack the snow and then I have to make sure that I driveacross that one certain place the entire winter. That is theonly way. Because if I drive or cross it over [the river] ina different area, it’s not as safe. (Seasonal Land User,west region)

The magnitude of changes and the hazards thesechanges have created (and will continue to create) affecting

Climate and Development 409

First Nations’ subsistence way of life have also providedthe impetus to plan appropriately for a changing environ-ment. First Nations’ engagement and perspectives are criti-cal in the planning and policy processes to address climatechange on territorial land.

Conclusion

First Nations observations about changes occurring on theland and water were strongly similar across the study areaand many discussions and descriptions focused on “blue-ice”. The term is embedded in their languages and is aselementary to life as water (only in a solid state) and is ameasuring stick for people’s activities on the land. Blue-ice ties transportation to food and energy security,whether to access modern goods and services or carry outtraditional activities. Blue-ice (and ice in general) histori-cally formed in the fall and remained until spring or overa period of six to eight months. Today, blue-ice formslater, disappears earlier, and its depth is less (almost byhalf as in the past), reducing both the timeline in frozenlakes and rivers, and its strength-bearing capacity. Travelconditions on frozen waterways and winter roads can beextremely hazardous even during months typically con-sidered the middle of winter (e.g. January).

The concept of “adaptation” found in the climatechange literature is foreign to First Nations in the northernboreal forest of Ontario. Indigenous peoples (and/or localcommunities) have for centuries managed and aligned thebenefits from the environment with human interests(Hawken & Granoff, 2010). Adaptation is not a word orconcept in their culture, yet it is inherent and necessary toliving on the land for these remote First Nations. Theterm adaptation also carries a negative connotation associ-ated with the history and influences from colonization tothese indigenous peoples.

The research team was challenged to use terms inkeeping with the First Nation worldview framed by theirconnection to the land. Comments from Elders on interpret-ing “the sound of the cold” made this relationship remark-ably clear. We transformed the term “adaptation” to“continuity” to reflect the indigenous connection to theland. Consistent with theories in complex adaptivesystems, First Nations’ understanding of, and interactionwith, the landscape takes place across temporal andspatial scales, in generational and first-hand knowledgeover a large geographic area and at a local level concerningblue-ice.

First Nations in the study recognized the need todevelop anticipatory reactions to rapid climate changeand to evolve activities in continuity with the land, whilestill staying the same as a people and retaining their culturalidentity. Changes in blue-ice are requiring adjustments, butthe indigenous worldview remains intact. The importantdistinction we make is that only activities in response to

climate change are applicable to the term adaptation (notFirst Nation people), and that in spite of adaptive changesto climate change, the First Nation worldview has remainedperpetual and resilient. Most important to the indigenouspeoples in this study is recognition of their right to a home-land from which they cannot be displaced and which iscentral to their identity.

Policy and decision-making in response to climatechange, to mitigate the extent of change and the adaptiveundertakings required, are arduous and fraught with uncer-tainty. A major contributing factor to the difficulties withthe decision-making is the integral complexity of ecologi-cal and social systems. The value of indigenous knowledgehanded down through generations in adapting to and miti-gating climate change, the application of traditional knowl-edge to modern climate change problems, and indigenousperspectives on adaptation have been discussed.However, climate change policy in Ontario is being devel-oped without meaningful and comprehensive consultationwith First Nations and does not address the issues high-lighted in this paper. This study illustrates the relevanceand uniqueness of First Nations knowledge about climatechange within their territory in relation to both their per-spective of continuity and to the rapidly changing con-ditions on the land. The importance of First Nations’involvement in climate change policies that will affecttheir territories and communities cannot be overstated,both as a constitutional requirement to protect Aboriginaland treaty rights, and in their knowledge in changes occur-ring in the sub-Arctic.

The absence of indigenous knowledge in the climatechange discourse and policy decisions may have a perverseoutcome. Excluding meaningful and broad participation byindigenous peoples perpetuates the dominant westernapproach to climate change adaptation and may limit theknowledge and information needed to identify key indi-cators in the complications, challenges, or solutions to theimpacts. Rather than non-indigenous people building adap-tation strategies from a western framework, or using tra-ditional knowledge where policy-makers deem itappropriate, space needs to be provided throughout theentire policy-making processes for First Nations’ perspec-tives. The new challenge for indigenous communities andwestern policy-makers is inclusion in the dialogue.

Fundamental to the dialogue is reframing the language,which in this case is from “adaptation” to “continuity”.Reframing the language would create a basis for discus-sions more meaningful to and respectful of First Nations,and facilitate the opportunity for greater understandingamongst policy-makers of the changes occurring in thenorthern boreal forest. It will require formulating strategiesand protocols in which First Nations are actively involvedin the policy process from the onset, and not just the reci-pients of policy decisions made by others. Policy-makersneed to give western and indigenous knowledge mutual

410 D.M. Golden et al.

respect and substantial consideration. First Nations conti-nuity with the land is relevant to addressing climatechange, potentially leading to more effective climatechange policies in Ontario, Canada, and the rest of theworld. It is time to build bridges across the disappearanceof “blue-ice” – kah-oh-shah-whah-skoh-siig mii-koom.

AcknowledgementsThis work was supported by the National Science and Engineer-ing Research Council (NSERC) Northern Internship ResearchProgram awarded to Denise M. Golden, Dr. Steve Colombo,Research Scientist, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources,Dr. R. Harvey Lemelin, Lakehead University Research Chairin Parks and Protected Areas and Nishnawbe Aski Nation(NAN) and the following communities for their contributionsin the research: Muskrat Dam First Nation, Weagamow FirstNation, Sandy Lake First Nation, Pikangikum First Nation,Nibinamik First Nation, Neskantaga First Nation, AttawapiskatFirst Nation, Fort Albany First Nation, Kingfisher Lake FirstNation and Wunnumin Lake First Nation. We also extend ourappreciation to two anonymous reviewers for their commentsand supportive input on previous versions of the manuscript,and to Han van Dijk.

Notes1. We use three different terms to cover indigenous peoples:

“indigenous”, as spelled out in the UN Declaration on theRights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007 (and adopted byCanada in 2010), “Aboriginal”, which is defined inCanada’s Constitution Act, 1982 to include “Indians,Métis, and Inuit”; and “First Nations”, which has no legaldefinition but has become the accepted term for “IndianBands” under the Indian Act (INAC, 2002); the commu-nities that were part of the study are all “First Nations”and consider themselves to be Ojibwe, Cree, and OjicreeNations. We therefore use the term First Nations and indi-genous interchangeably.

2. NAN Launches Anti-Bill 191 Campaign News Release,Tuesday, August 31, 2010, Thunder Bay, ON.

3. Climate change mitigation is the reduction, prevention, andremoval of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, whereasadaptation is planning and preparing for climate changeimpacts to lessen the impact or capitalize on theopportunities.

4. Respectfully acknowledged, unavoidable community cir-cumstances took precedence over the research; manytimes the winter road opened creating an exodus of commu-nity members (both and/or interviewees and translators) toobtain much needed supplies, or sadly a death occurredand all community activities halted, including interviews,except those to mourn.

5. Sub-Arctic geography retrieved from Natural ResourcesCanada, The Atlas of Canada Climatic Regions http://atlas.nrcan.gc.ca/site/english/maps/archives/3rdedition/environment/climate/030.

6. Land elevations were taken from topographical maps TheAtlas of Canada, Natural Resources Canada; Retrievedfrom http://atlas.nrcan.gc.ca/site/english/maps/topo/map.

7. The Köppen Climate Classification information as devel-oped by German geographer Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) continues to be the authoritative map of the world

climates in use today; Retrieved from http://www.elmhurst.edu/~richs/EC/101/KoppenClimateClassification.pdf.

8. The UN Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on IndigenousPeoples (2009) reports 370 million indigenous peoples livewithin 90 countries around the world.

9. Eight of the 10 communities are located inland and situatednext to lakes or rivers; 2 communities are located on theJames Bay Coast at the mouth of major rivers – theAlbany and Attawapiskat.

10. Comments and recollections from community membersincluded ice strong enough to walk across within daysafter temperatures became very cold – the blue-ice trustedfor its strength, lasting for many months.

11. Notes taken during a discussion Muskrat Dam, ON, January19, 2011.

12. Canadian retail gasoline prices in 2011 averaged $1.24/litre;Fuel Focus, 2011 Annual Review, Natural ResourcesCanada. Retrieved from http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/energy/fuel-prices/gasoline-reports/4733.

13. The Globe and Mail Canadian Press. Sunday, December 02,2012. Neighbouring reserve to Attawapiskat narrowlyavoids fuel, housing crisis. Retrieved from http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/neighbouring-reserve-to-attawapiskat-narrowly-avoids-fuel-housing-crisis/article5899087/.

14. One culturally appropriate response would be how FirstNations address changes in hunting areas because of wild-life habitat changes.

15. The Gradual Civilization Act sought to assimilate Aborigi-nal people (Indians) into Canadian settler society byencouraging “enfranchisement”, a legal process for termi-nating a person’s Indian status; Retrieved from http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/?id=1053.

16. FPIC is the principle that indigenous peoples and local com-munities have a right to give or withhold their free, prior,and informed consent to developments or potential effectsby an external initiative or influence outside the community;Retrieved from http://www.recoftc.org/site/resources/FPIC-in-REDD-/.

ReferencesAbel, N., Cumming, D., & Anderies, J. (2006). Collapse and reor-

ganization in social-ecological systems: Questions, someIdeas, and policy implications. Ecology and Society, 11(1),17 [online]. Retrieved from http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss1/art17/

Adger, W.N., Arnell, N.W., & Tompkins, E.L. (2005). Successfuladaptation to climate change across scales. GlobalEnvironmental Change, 15(2), 77–86. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.12.005

Adger, W.N., Brown, K., Nelson, D.R., Berkes, F., Eakin, H.,Folke, C.,… Tompkins, E.L. (2011). Resilience implicationsof policy response to climate change. Climate Change, 2(5),757–766.

Applied History Research Group. (2000, 2001). Canada’s firstnations: Antiquity: Prehistoric periods (Eras of Adaptation).University of Calgary and Red Deer College, Calgary, AB.Retrieved February 22, 2013, from http://www.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tutor/firstnations/

Berkes, F. (2009). Indigenous ways of knowing and the study ofenvironmental change. Journal of Royal Society of NewZealand, 39(4), 151–156.

Climate and Development 411

Berkes, F., Colding, J., & Folke, C. (2000). Rediscovery of tra-ditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management.Ecological Applications, 10(5), 1251–1262.

Bohensky, E.L., & Maru, Y. (2011). Indigenous knowledge,science, and resilience: What have we learned from adecade of international literature on integration? Ecologyand Society, 16(4), 6 [online]. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-04342-160406

Botha, L. (2011). Mixing methods as a process towards indigen-ous methodologies. International Journal of SocialResearch Methodology, 14(4), 313–325.

Brook, R., & McLachlan, S. (2008). Trends and prospects forlocal knowledge in ecological and conservation researchand monitoring. Biodiversity and Conservation, 17(14),3501–3512.

Carpenter, S., Walker, B., Anderies, M., & Abel, N. (2001). Frommetaphor to measurement: Resilience of what to what.Ecosystems, 4, 765–781.

Chinn, P. (2007). Decolonizing methodologies and Indigenousknowledge: The role of culture, place and personal experiencein professional development. Journal of Research in ScienceTeaching, 44(9), 1247–1268.

Cobb, D., Kisalioglu, M., & Berkes, F. (2005). Ecosystem-basedmanagement and marine environmental quality indicators innorthern Canada. In F. Berkes, R. Huebert, H. Fast, M.Manseau, & A. Diduck (Eds.), Breaking ice: Renewableresource and ocean management in the Canadian North(pp. 71–94). Calgary, AB: University of Calgary Press.

Cochran, P.A.L., Marshall, C.A., Garcia-Downing, C., Kendall, E.,Cook, D., McCubbin, L., & Gover, R.M. (2008). Indigenousways of knowing: Implications for participatory research andcommunity. American Journal of Public Health, 98(1), 22–27. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18048800

Constitution Act. (1982). Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982, (U.K.) 1982, c. 11.

Crate, S. (2008). Gone the bull of winter? Grappling with the cul-tural implications of and anthropology’s role(s) in globalclimate change. Current Anthropology, 49(4), 569–595.

Cruikshank, J. (2001). Glaciers and climate change: Perspectivesfrom oral tradition. Arctic, 54(4), 377–393.

Davidson, D., Diffenbaugh, N., Kinney, P., Kirshen, P., Kovacs,P., & Villers-Ruiz, L. (2014). Working Group II to the AR5(WGII AR5), Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation,and Vulnerability. Chapter 26. p. 88.

Davidson-Hunt, I., & Berkes, F. (2003). Learning as you journey:Anishinaabe perception of social-ecological environmentsand adaptive learning. Conservation Ecology, 8(1), 5[online]. Retrieved from http://www.consecol.org/vol8/iss1/art5/

Devkota, R.P., Bajracharya, B., Maraseni, T.N., Cockfied, C., &Upashyak, B.R. (2011). The perception of Nepal’s Tharucommunity in regard to climate change and its impacts ontheir livelihoods. International Journal of EnvironmentalStudies, 68(6), 937–946.

Downing, A., & Cuerrier, A. (2011). A synthesis of the impacts ofclimate change on first nations and Inuit of Canada. IndianJournal of Traditional Knowledge, 10(1), 57–70.

Dowsley, M. (2009). Community clusters in wildlife and environ-mental management: Using TEK and community involve-ment to improve management in an era of rapidenvironmental change. Polar Research, 28, 43–59.

Engle, N.L. (2011). Adaptive capacity and its assessment. GlobalEnvironmental Change, 21(2), 647–656. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.019

Fischlin, A., Midgley, G.F., Price, J.T., Leemans, R., Gopal, B.,Turley, C.,…Velichko, A.A. (2007). Ecosystems, their prop-erties, goods, and services. In M. L. Parry, O. F. Canziani, J. P.Palutikof, P. J. van der Linden, & C. E. Hanson (Eds.),Climate change 2007: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability.Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth AssessmentReport of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change(pp. 211–272). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Folke, C., Carpenter, S.R., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Chapin, T., &Rockström, J. (2010). Resilience thinking: Integrating resili-ence, adaptability and transformability. Ecology and Society,15(4), 20 [online]. Retrieved from http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art20/

Folke, C., Pritchard, L., Berkes, F., Colding, J., & Svedin, U.(2007). The problem of fit between ecosystems and insti-tutions: ten years later. Ecology and Society, 12(1), 30[online]. Retrieved December 3, 2013, from http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol12/iss1/art30/

Galloway McLean, K., Ramos-Castillo, A., & Rubis, J. (2011).Indigenous peoples, marginalized populations and climatechange: Vulnerability, adaptation and traditional knowledgemeeting report. July 19–21, 2011, Mexico City, Mexico.IPMPCC/2011/Mex/Report. Retrieved February 25, 2013,from 2013 http://www.unutki.org/downloads/File/2011_IPMPCC_Mexico_Workshop_Summary_Report_web.pdf

Gudra, T., & Najwer, L. (2011). Ultrasonic investigation ofsnow and ice parameters. Acta Physica Polonica A, 120(4),625–629.

Hartvigsen, G., Kinzig, A., & Peterson, G. (1998). Use and analy-sis of complex adaptive systems in ecosystem science:Overview of special section. Ecosystems, 1(5), 427–430.

Hawken, I.F., & Granoff, I.M.E. (2010). Reimagining park ideals:Toward effective human-inhabited protected areas. Journal ofSustainable Forestry, 29(2), 122–134.

Henry, C., Meakin, S., &Mustonen, T. (2013). Indigenous percep-tions of resilience. Arctic Resilience Interim Report 2013,27–34. Retrieved from http://www.sei-international.org/mediamanager/documents/Publications/ArcticResilienceInterimReport2013-LowRes.pdf

Huntington, H.P. (2000). Using traditional and ecological knowl-edge in science: Methods and applications. EcologicalApplications, 10(5), 1270–1274.

Huntington, H., Callaghan, T., Fox, S., & Krupnik, I. (2004).Matching traditional and scientific observations to detectenvironmental change: A discussion on Arctic terrestrial eco-systems. Ambio Special Report, 13, 18–23.

Huntjens, P., Lebel, L., Pahl-Wostl, C., Camkin, J., Schulze, R., &Kranz, N. (2012). Institutional design propositions for thegovernance of adaptation to climate change in the watersector. Global Environmental Change, 22(1), 67–81. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.09.015

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC). (2002). Words first:An evolving terminology relating to aboriginal peoples inCanada. Retrieved February 26, 2013, from http://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/R2–236–2002E.pdf

Kwiatkowski, R. (2011). Indigenous community based participa-tory research and health impact assessment: A Canadianexample. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 31(4),445–450.

Lemos, M.C., Boyd, E., Tompkins, E.L., Osbahr, H., & Liverman,D. (2007). Developing adaptation and adapting development.Ecology and Society, 12(2), 26. Retrieved February 18, 2013,from http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol12/iss2/art26/

Levina, E., & Tirpak, D. (2006). Adaptation to climate change:Key terms. Organization for Economic Co-operation and

412 D.M. Golden et al.

Development (OECD) and International Energy Agency,Paris, France. Retrieved April 14, 2013, from http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/36/53/36736773.pdf

Liu, J., Dietz, T., Carpenter, S.R., Folke, C., Alberti, M., Redman,C.L.,… Provencher, W. (2007). Coupled human and naturalsystems. Ambio, 36(8), 639–649.

Macchi, M., Oviedo, G., Gotheil, S., Cross, K., Boedhihartono,A., Wolfangel, C., & Howell, M. (2008). Indigenous and tra-ditional peoples and climate change. Issues Paper.International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN),Gland, Switzerland. Retrieved April 15, 2013, from http://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/indigenous_peoples_climate_change.pdf

Mueller, D.R., & Vincent, W.F. (2003). Break-up of the largestArctic ice shelf and associated loss of an Epishelf lake.Geophysical Research Letters, 30(20). doi:10.1029/2003GL017931

Nakashima, D.J. (1993). Astute observers on the sea ice edge: Inuitknowledge as a basis for Arctic co-management.. In J.T. Inglis(Ed.), Traditional ecological knowledge: Concepts and cases(pp. 99–110). Ottawa, ON: International DevelopmentResearch Centre. Retrieved February 14, 2013, from http://web.idrc.ca/panasia/ev-84414–201–1-DO_TOPIC.html

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). (n.d.).Earth observatory global temperatures. Retrieved June 23,2013, from http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/WorldOfChange/decadaltemp.php

Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN). (1977). Declaration of theNishnawbe Aski. Thunder Bay, Canada. Retrieved February22, 2013, from http://www.nan.on.ca/article/a-declaration-of-nishnawbeaski-431.asp

Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN). (2011). About us. RetrievedFebruary 22, 2013, from http://www.nan.on.ca

O’Brien, K., Hayward, B., & Berkes, F. (2009). Rethinking socialcontracts: Building resilience in a changing climate. Ecologyand Society, 14(2), 12. Retrieved April 20, 2014, from http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss2/art12/

Office of the United Nations High Commission on Human Rights(OHCHR). (2009). Report of the Office of the United NationsHigh Commissioner for Human Rights on the Relationshipbetween Climate Change and Human Rights (A/HRC/10/61). Retrieved July 4, 2013, from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/HRAndClimateChange/Pages/Study.aspx

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR). (2011). The farnorth Act, 2010. Retrieved April 10, 2014, from http://www.mnr.gov.on.ca/en/Business/FarNorth/2ColumnSubPage/STDPROD_068663.html

Park, S.E., Marshall, N.A., Jakku, E., Dowd, A.M., Howden, S.M., Medham, E., & Fleming, A. (2012). Informing adaptationresponses to climate change through theories of transform-ation. Global Environmental Change, 22(1), 115–126.

Pearce, T.D., Ford, J.D., Laidler, G.J., Smit, B., Duerden, F., Allarut,M.,…Wandel, J. (2009).Community collaboration and climatechange research in the Canadian Arctic. Polar Research, 28(1),10–27. doi:10.1111/j.1751–8369.2008.00094.x

Pretty, J. (2011). Interdisciplinary progress in approaches toaddress social-ecological and ecocultural systems.Environmental Conservation, 38(2), 127–139.

Sakakibara, C. (2011). Singing for the Whales: Environmentalchange and cultural resilience among the Iñupiat of ArcticAlaska in IPMPCC Workshop Report July 19–21, 2011.Mexico City, Mexico. p. 47. Retrieved February 22, 2013,from http://www.unutki.org/downloads/File/2011_IPMPCC_Mexico_Workshop_Summary_Report_web.pdf

Salem-Wiseman, L. (1996). Verily, the white man’s ways were thebest”: Duncan Campbell Scott, native culture, and assimila-tion. Studies in Canadian Literature, 21(2), 120–142.

Smit, B., & Pilifosova, O. (2001). Adaptation to climate change inthe context of sustainable development and equity.. In J.A.McCarthy, O.F. Canziani, N.A. Leary, D.J. Dokken, & K.S.White (Eds.), Climate change 2001: Impacts, adaptationand vulnerability. International panel on climate changereport (pp. 887–912). Cambridge University Press.Retrieved February 22, 2012, from http://www.ipcc.ch/ipccreports/tar/wg2/pdf/wg2TARchap18.pdf

Tobias, J.L. (1976). Protection, civilization, assimilation: Anoutline history of Canada’s Indian policy. Western CanadianJournal of Anthropology, 6(2), 39–53.

Tremblay, M., Furgal, C., Lafortune, V., Larrivée, C., Savard, J.P.,Barrett, M.,… Etidloie, B. (2006). Communities and ice:Bringing together traditional and scientific knowledge. In R.Riewe & J. Oakes (Eds.), Climate change: Linking traditionaland scientific knowledge (pp. 123–138). Manitoba:Aboriginal Issues Press, University of Manitoba.

Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for ResearchInvolving Humans (TCPS-2): Chapter 9. Research involvingthe first nations, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada. HerMajesty the Queen in Right of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario.Retrieved from http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/eng/policy-politique/initiatives/tcps2-eptc2/chapter9-chapitre9/#toc09–1a

Walker, B., Holling, C.S., Carpenter, S.R., & Kinzig, A. (2004).Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social-eco-logical systems. Ecology and Society, 9(2), 5. RetrievedFebruary 22, 2013, from http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss2/art5

Winter, R., & Munn-Giddings, C. (2001). Handbook for actionresearch in health and social care. London: Routledge.

Yu, J., Liu, H., Jezek, K., & Heo, J. (2012). Blue ice areas andtheir topographical properties in the Lambert glacier, AmeryIceshelf system using Landsat ETM1, ICESat laser altimetryand ASTER GDEM data. Antarctic Science, 24(1), 95–110.

Climate and Development 413