Another Look at Toyota Product Development

-

Upload

casarrubiasv -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

Transcript of Another Look at Toyota Product Development

8/10/2019 Another Look at Toyota Product Development

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/another-look-at-toyota-product-development 1/12

Another Look at How Toyota

Integrates Product Developmentby Durward K. Sobek, II, Jeffrey K. Liker, and Allen C. Ward

Harvard Business Review Reprint 98409

8/10/2019 Another Look at Toyota Product Development

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/another-look-at-toyota-product-development 2/12

8/10/2019 Another Look at Toyota Product Development

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/another-look-at-toyota-product-development 3/12

Copyright © 1998 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. 3

I D E A S A T W O R K

A great many companies attackedthe issue head on. Typical solutionswere such product-developmenttools as quality function deploy-ment and Taguchi methods. Compa-nies also introduced organizationalsolutions; those solutions rangedfrom keeping the basic functionalorganization intact and assigningpeople to temporary project teams to

disbanding the functional organiza-tion altogether in favor of organizingaround products, as Chrysler did inthe early 1990s. (Here we use the term

function broadly to mean the vari-ous groups of specialized expertiserequired to make new models work –including the engineering special-

ties within the design process, suchas electrical, body, or test engineer-ing, as well as other business func-tions, such as manufacturing andmarketing.)

The new solutions have broughtsubstantial improvements to thecompanies and dramatic results inthe marketplace. But they havealso created problems of their own.

Cross-functional coordination hasimproved, but at the cost of depth ofknowledge within functions, be-cause people are spending less timewithin their functions. Organiza-tional learning across projects hasalso dropped as people rotate rapidlythrough positions. Standardization

across products has suffered becauseproduct teams have become auton-omous. In organizations that combinefunctional and project-based struc-tures, engineers are often torn be-tween the orders of their functionalbosses on the one hand and the de-mands of project leaders on the other.As these new problems take theirtoll, U.S. companies are beginning

to see the effectiveness of their prod-uct-development systems plateau.More important, that effectivenessseems to have leveled off far short ofthe best Japanese companies.

This article explores how one ofthose companies, Toyota, managesits vehicle-development process. We

8/10/2019 Another Look at Toyota Product Development

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/another-look-at-toyota-product-development 4/12

studied Toyota’s process for fiveyears through in-depth interviews atall levels of management. Interest-ingly, we found that in many waysthe company does not resemblewhat is often considered the modelof Japanese product development– it

has maintained a functionally basedorganization while achieving its im-pressive degree of integration, andmany of its practices are actuallysimilar to those that U.S. companiesemployed during their manufactur-ing prime earlier in this century.

We can group Toyota’s managerialpractices into six organizationalmechanisms. Three of them are pri-marily social processes: mutual ad-justment, close supervision, and in-tegrative leadership from productheads. The other three are forms of

standardization: standard skills,standard work processes, and designstandards. Alone, each mechanismwould accomplish little, but everypiece has its own role and at thesame time reinforces the others, un-like many of the sophisticated toolsand practices at companies in theUnited States, which tend to be im-plemented independently.

Together, the mechanisms giveToyota a tightly linked product-development system that achievescross-functional coordination while

still building functional expertise.This balance allows the company to

achieve integration across projects

and over time, as well as withinprojects. U.S. companies have con-centrated on bringing the functionstogether within projects, but a single-minded focus on that goal can actu-ally undermine attempts to shareinformation across projects. Cross-functional teams, for example, workwell within individual projects, butthe temporary, personal nature ofthese teams makes it hard for them

to transmit information to teams onother projects.

Toyota, by contrast, seems to go tothe opposite organizational extreme.It relies on highly formalized rulesand standards, and puts limits on theuse of cross-functional teams. Such

rigid policies can have enormousdrawbacks. To avoid those draw-backs, Toyota has added a number oftwists to ensure that each projecthas the flexibility it needs and stillbenefits from what other projectshave learned. The result is a deftlymanaged process that rivals thecompany’s famous production sys-tem, lean manufacturing, in effec-tiveness.

Coordination Based onWriting

One of the most powerful ways tocoordinate one’s efforts with thoseof people in other functions is to talkto them face to face. In this manner,each party gets the other’s point ofview and can quickly make adjust-ments to find common ground. Thismutual adjustment often takes theform of a meeting: a product designerand a manufacturing engineer, forexample, get together to discuss theeffects that a proposed design for aparticular car body would have onthe cost of production.

Direct contact between the mem-bers of different functions is cer-

tainly important – somesay it is the essential in-gredient in getting func-tional groups that havetraditionally been at oddsto work together. Indeed,many observers, manag-ers, and engineers claimthat face-to-face interac-tion is the richest, mostappropriate form of com-

munication for product develop-

ment. Numerous companies nowcolocate functional experts so thatinteraction can occur with muchgreater ease and frequency. Oftenthese companies have done awaywith written forms of communica-tion because, as some claim, writtenreports and memos do not have therichness of information or interac-tive qualities needed for productdevelopment.

Meetings, however, are costly interms of time and efficiency, andmeeting time increases with coloca-tion. Meetings usually involve lim-ited value-added work per person,and they easily lose focus and dragon longer than necessary. Engineers

in companies we’ve visited oftencomplain of not having enough timeto get their engineering work donebecause of all the meetings in theirschedule.

Toyota, by contrast, does not co-locate engineers or assign them todedicated project teams. Most peo-ple reside within functional areasand are simply assigned to work onprojects – often more than one at atime– led by project leaders. By root-ing engineers in a function, the com-pany ensures that the functions de-

velop deep specialized knowledgeand experience.

In lieu of regularly scheduledmeetings, the company emphasizeswritten communication. When anissue surfaces that requires cross-functional coordination, the proto-col is first to write a report that pre-sents the diagnosis of the problem,key information, and recommenda-tions, and then to distribute thisdocument to the concerned parties.Usually, the report is accompaniedby either a phone call or a short

meeting to highlight the key pointsand emphasize the importance ofthe information. The recipient is ex-pected to read and study the docu-ment and to offer feedback, some-times in the form of a separatewritten report. One or two iterationscommunicate a great deal of infor-mation, and participants typicallyarrive at an agreement on most, ifnot all, items. If there are outstand-ing disagreements, then it’s time tohold a meeting to hammer out a de-cision face to face.

In such problem-solving meet-ings, participants already under-stand the key issues, are all workingfrom a common set of data, and havethought about and prepared propos-als and responses. The meeting canfocus on solving the specific prob-lem without wasting time bringingpeople up to speed. By contrast, atmany U.S. companies, attendeesoften arrive at meetings having done

4 harvard business review July–August 1998

how toyota integrates product developmentI D E A S A T W O R K

Toyota combines a highly

formalized system with twists

to ensure that each project

is flexible and benefits from

other projects.

8/10/2019 Another Look at Toyota Product Development

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/another-look-at-toyota-product-development 5/12

little or no preparation. They canspend the first half of the meetingjust defining the issue, and responsesare shoot-from-the-hip reactions toa problem that people have had littletime to think about.

Toyota takes its focused style of

meeting quite seriously. One engi-neer we talked to showed us hisschedule for the day, which includedtwo meetings at separate times withthe same group of people. Whenasked why he would schedule sepa-rate meetings with this group, heexplained that they needed twomeetings to discuss two distinctproblems. It was important not toconfuse the issues by combiningthem into one meeting.

Once the writer of the originalreport has consulted with all inter-

ested parties, he or she writes a finalversion of the report that presents allsides of the question. The overallreporting process therefore has twobenefits. First, it documents andsummarizes analysis and decisionmaking in a convenient form for therest of the organization. Second, andmore important, it forces engineersin every function to gather opinionsfrom other functions regarding theramifications of the changes they areproposing.

Twist: Although Toyota often re-

lies on written communication asthe first line of attack in solvingproblems, it does not suffer from thevoluminous paperwork we associatewith bureaucracy. In most cases, en-gineers write short, crisp reports onone side of size A3 paper (roughly11 ´ 17, the largest faxable size). Thereports all follow the same format sothat everyone knows where to findthe definition of the problem, the re-sponsible engineer and department,the results of the analysis, and therecommendations. The standard for-

mat also helps engineers make surethey have covered the important an-gles. The result is a clear statementof a problem and solutions that isaccessible not only to people withina particular project but also to thoseworking on other projects.

Writing these reports is a difficultbut useful skill, so the companygives its engineers formal training inhow to boil down what they want to

communicate. Supervisors see to itthat engineers do the appropriategroundwork to ensure that all perti-nent views are taken into considera-tion. Toyota has also created a cul-ture in which reading these reportsis highly valued and essential to do-

ing one’s job well. Indeed, we heardabout a certain Toyota executive whorefused to read any report longer thantwo pages.

Mentoring SupervisorsIn product development, supervi-sion traditionally took place withinindividual functions. Electrical engi-neers, for example, were supervisedby other electrical engineers becauseonly they fully understood the workinvolved. Recently, some U.S. com-panies have experimented with

cross-functional team-based organi-zations in order to force engineersto think beyond the needsof their own function.Chrysler, for example, isorganized around productplatforms rather thanfunctions, and the plat-form team leader heads allproduct engineering inthe platform.

Toyota, however, has not forgot-ten the value of instructive supervi-sion within functions. Supervisors

and higher-level managers aredeeply involved in the details of en-gineering design. In fact, young engi-neers (anyone with less than tenyears’ experience) must usually getapproval from their functional su-pervisors not only for the designsthey propose but also for each stepinvolved in the process of arriving atthe final design.

The company depends on supervi-sors to build deep functional exper-tise in its new hires– expertise thatthen facilitates coordination across

functions. But functional supervi-sors also teach engineers how towrite reports, whom to send the re-ports to, how to interpret reportsfrom other functions, and how toprepare for meetings. Direct supervi-sion thus works in concert with mu-tual adjustment in order to promotecoordination.

Twist: To American eyes, such in-tensive supervision would seem to

be a kind of meddling that stifles thecreativity and learning of new engi-neers and other specialists. U.S.companies are moving in the oppo-site direction as they preach em-powerment, with superiors acting asfacilitators rather than bosses. But

Toyota has succeeded in keeping itssupervision fresh and engaging, intwo ways. Like Toyota’s supervisorson the factory floor, managers inproduct development are workingengineers. Instead of merely manag-ing the engineering process, theyhone their engineering skills, stayabreast of new technology, maintaintheir contacts and develop new ones,and remain involved in the creativeprocess itself. Functional engineersare not frustrated by the experienceof working under someone less

skilled than they are. In many U.S.companies, by contrast, engineers

who rise through the ranks becomemanagers who stop doing engineer-ing work.

Perhaps more important, Toyota’s

managers seem to avoid making de-cisions for their subordinates. Theyrarely tell subordinates what to doand instead answer questions withquestions. They force engineers tothink about and understand theproblem before pursuing an alterna-tive, even if the managers alreadyknow the correct answer. It’s not aboss-subordinate or even a coach-athlete relationship, but a student-mentor relationship.

Integrative Leaders

Perhaps the most powerful way tointegrate the work of people fromdiverse specialties is to have a leaderwith a broad overview of the whole.Many U.S. companies have recentlybeen moving toward a heavyweight-

pr oj ec t- ma na ge me nt structure.Heavyweight project managers coor-dinate all the specialists from func-tional departments around a com-mon project with a common set of

Supervisors are deeply

involved in their subordinates’

work, without giving orders.

how toyota integrates product development I D E A S A T W O R K

harvard business review July–August 1998 5

8/10/2019 Another Look at Toyota Product Development

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/another-look-at-toyota-product-development 6/12

goals. Their authority in these ma-trix organizations comes from theircomplete control over their particu-lar project rather than from any di-rect supervisory authority over theindividual functions.

Toyota’s equivalent is the chief

engineer. Each chief engineer, basedin one of Toyota’s three vehicle-development centers (which overseelong-term planning across projects),maintains full responsibility for asingle vehicle program but wields nodirect power over the functions.

Indeed, Toyota’s chief engineerscome close to matching what othershave described as the prototypicalheavyweight project manager. Be-fore attaining their position, theymust demonstrate both exemplarytechnical expertise and fluency in

synthesizing technical knowledgeinto clever, innovative designs. Toy-ota’s managers feel strongly that

only a good designer can evaluatethe quality of someone else’s design.Chief engineers also need to be able

to conceptualize whole systems. Itis one thing to understand the me-chanics of a brake system and an-other to apply that knowledge to-ward an actual brake system design;but it is quite another thing to beable to conceptualize a brake systemand visualize how it can be integratedwith the rest of the vehicle. By con-trast, a number of companies withheavyweight product managers donot have such stringent technical re-quirements.

All chief engineers have a small

staff of 5 to 15 engineers to assistthem in managing the developmentprocess and in coordinating thework of the functional specialties.The hundreds of other engineers onthe project report only through thefunctional chain of command. Thechief engineer has no formal author-ity over them, so he must “per-suade” them to help him realize hisvision for the vehicle. One former

chief engineer described the positionas being the “president of the vehi-cle”: just as the U.S. president headsthe country but has no direct author-ity over legislation (beyond vetoes),so a chief engineer cannot dictatewhat functional engineers do. But

his extensive technical expertisewins him tremendous respect, evenadmiration, from functional engi-neers– a key source of his enormousinformal authority.

The limits on the chief engineers’power, despite their prestige, arereal, and the engineering expertiseand equal rank of the general man-agers in charge of the functionalareas can keep chief engineers frommaking potentially dangerous mis-takes. For example, in designing anew model of the Celica sports car

several years ago, the styling depart-ment suggested a longer front-quarter panel. The change would

have increased the panel’sextension into the top ofthe front door, allowingthe door to curve back atthe top, thereby creatingan angular and more ex-citing look. The manufac-turing engineer assigned

to door panels, however, opposed thechange because the altered panelwould be difficult to produce.

After assessing both sides, thechief engineer for the vehicle fa-vored the altered front panel. Never-theless, the manufacturing engineerfelt strongly that the change was un-wise. If Toyota had organized aroundprojects rather than functions,styling would likely have gotten itsway, and the car might well havesuffered production problems. Butbecause the chief engineer’s author-ity was only informal, the manufac-turing engineer was able to raise theissue to the level of the general man-

ager of manufacturing, who stronglychallenged the chief engineer. Aftersubstantial argument, the two sidesreached an innovative compromisethat achieved the cutaway look thatstyling wanted with a satisfactorylevel of manufacturability.

Such incidents explain why oneToyota engineer, when asked whatmakes a good car, replied,“Lots of con-flict.” Conflict occurs when people

6 harvard business review July–August 1998

how toyota integrates product developmentI D E A S A T W O R K

A chief engineer is less the

manager of and more the

lead designer on a project.

from different functional areasclearly represent the issues fromtheir perspective. Its absence im-plies that some functional areas arebeing too accommodating – to thedetriment of the project as a whole.Still, when managers resolve con-

flicts through organizational influ-ence, horse trading, or executivefiat, the results are often poor. It isthe ability of chief engineers to seethe broad picture clearly – and theability of functional managers tocontain the chief engineer’s enthu-siasm– that leads to highly integrat-ed designs. And while the chief en-gineers keep individual projects ontrack, the autonomous functional

8/10/2019 Another Look at Toyota Product Development

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/another-look-at-toyota-product-development 7/12

decisions. His authority over designdecisions stems from the fact thatthe vehicle is quite clearly “his car.”He is therefore less the manager ofand more the lead designer on theoverall project.

As lead designer, chief engineers

design (and subsequently manage)the entire process of developing theproduct, and they personally articu-late the vehicle concept that be-comes the blueprint for the entireprogram. That concept includes themajor dimensions of the vehicle; de-cisions on such major systems as thetransmission; the variety of modelsto be offered; the characteristics ofthe target customer; sales projec-tions; and targets on weight, cost,and fuel economy. Chief engineersintegrate the work of the functions

by planning how all the parts willwork together as a cohesive whole,soliciting input from the various en-gineering, manufacturing, and mar-keting functions, of course. Once achief engineer has designed the over-all approach for a car, the differentfunctions fill in the technical detailsthat are required to realize the vehi-cle concept.

Some of the remaining integrationproblems at U.S. companies may infact stem from a lack of preciselythis kind of system design. Even

companies with able heavyweightproduct managers tend to jump di-rectly from product concept to thetechnical details of engineering de-sign. They bypass, without goingthrough, the very difficult but im-portant task of designing the overallvehicle system: planning how all theparts will work together as a cohe-sive whole before sweating the finedetails. At Toyota, the chief engi-neer provides the glue that binds thewhole process together.

Standard SkillsEvery company depends on highlyskilled engineers, designers, andtechnicians to bring a product tomarket. Organizations can coordi-nate their activities by giving eachperson within a specialty the sameset of skills to accomplish his orher tasks. When we know what toexpect of others because they aretrained in a certain way, we can re-

quest specific services with relativelylittle effort in coordination. In engi-neering, most U.S. companies relyheavily on universities or special-ized training companies to providetheir people with the skills neededto do their jobs.

Toyota, by contrast, relies primar-ily on training within the company.It views training as a key compe-tency, worth developing internallyrather than outsourcing. Engineersreceive most of their training throughthe intensive mentoring involved indirect supervision, although thecompany also runs a training centerwith instructors who are experi-enced Toyota engineers. The processnot only develops excellent engi-neers but also teaches new hiresToyota’s distinct approach to devel-

oping the body, chassis, or other sys-tems in a vehicle.

Additionally, Toyota rotates mostof its engineers within only onefunction, unlike U.S. companies,which tend to rotate their peopleamong functions. Body engineers,for example, will work on differentauto-body subsystems (for example,door hardware or outer panels) formost, if not all, of their careers. Be-cause most engineers rotate primar-ily within their engineering func-tion, they gain the experience that

encourages standard work, makingthe outputs of each functional grouppredictable to other functions. Inaddition, rotations generally occurat longer intervals than the typicalproduct cycle so that engineers cansee and learn from the results oftheir work.

That consistency over time meansthat the company’s engineers in themanufacturing division, for exam-ple, need to spend less time and en-ergy communicating and coordinat-ing with their counterparts in design

because they learn what to expectfrom them. Indeed, Toyota firmlybelieves that deep expertise in engi-neering specialties is essential to itsproduct-development system. Weoften heard such comments as, “Ittakes ten years to make a body engi-neer” in our conversations with thecompany’s managers. In short, thewidely held notion that Japanesecompanies rotate their personnel

harvard business review July–August 1998 7

how toyota integrates product development I D E A S A T W O R K

engineers and managers ensure thatknowledge and experience fromother projects are not forgotten inthe current one.

Twist: Chief engineers do differ inone important respect from even thebest heavyweight project managers.

The latter typically delegate deci-sion making to functional teams,while retaining authority over theteam’s decisions and taking respon-sibility for implementing those deci-sions throughout the developmentprocess. If a heavyweight projectmanager doesn’t like a decision, heor she can veto it. By contrast, a chiefengineer takes the initiative bypersonally making key vehiclewide

8/10/2019 Another Look at Toyota Product Development

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/another-look-at-toyota-product-development 8/12

broadly and frequently simply doesnot apply to Toyota.

Twist #1: Rotating locally andbuilding functional expertise wouldseem to create rigid functionalboundaries, or chimneys, in whichengineers work only to be the best

in their function. An electrical engi-neer, for example, might aim to de-velop the most elaborate electricaldesign possible, without thinkingabout how that design will workwith the rest of the vehicle. But wehave found that the so-called chim-ney effect is not the result of youngengineers being too loyal to theirfunctions or too narrow-mindedabout what cars need. Rather, it isusually the result of experienced en-gineers and managers hoarding theirknowledge, which becomes the ba-

sis of their power in an organizationrooted in functions.

To avoid such political conflict,Toyota takes care to rotate most of

its senior people broadly. Engineersat the bucho level – which usuallymeans the head of a functional divi-sion (for example, power-train engi-neering for front-wheel-drive pas-senger cars) with at least 20 years’experience– typically rotate widelyacross the company to areas outsidetheir expertise. Such moves forcebuchos to rely heavily on the expertsin their new area, building broad net-works of mutual obligation. At thesame time, buchos bring their own

experience, expertise, and networkof contacts that they can use to facil-itate integration.

Twist #2: Buchos (and chief engi-neers) encourage their people to seethe needs of the product as a whole,but Toyota also keeps design engi-neers aware of the ramifications oftheir decisions throughout the de-velopment process. These engineersretain responsibility for their parts

of the car from the concept stage tothe start of full production. A door-systems engineer, for example,works with stylists to determine theconcept of the door and then devel-ops the detailed design by workingwith production engineers and out-

side suppliers. The engineer alsogoes to the factory to be part of thelaunch team as the vehicle ramps upto full production.

Flexible Work StandardsThe stereotypical bureaucratic wayof coordinating work processes is tospecify in detail the content of eachstep in the process. Tasks are prepro-grammed so that one group knowswhat to expect from another andwhen to expect it, with little or nocommunication required. Factories

use this kind of coordination exten-sively, standardizing the tasks ateach workstation to ensure that thework is done consistently and in a

set amount of time. Allthe workstations can thenbe easily coordinated by aschedule.

Many U.S. companieshave tried to apply thisconcept to product devel-opment, notably GeneralMotors with its fo ur-

phase process. A special

team at GM defines theprocess in great detail, telling eachdepartment what it needs to dowhen, whom to send results to, whatformat the information should take,and so on. The plan for the stylingfunction alone covers the length ofone wall in a sizable conferenceroom. The four-phase process is al-most never followed as its authorsenvisioned, however, because theprocess is so detailed that every ve-hicle program has exceptions thatforce designers to deviate from the

prescribed process – the real worldresists such intensive planning. Inaddition, a separate group developsand maintains the details of thestandard process; as a result, the peo-ple who must follow the process donot have ownership of it, and theprescribed processes are not likely tobe truly representative of the actualone. Indeed, the four-phase processseems to do little to shorten cycle

times or to bring other benefits thatsuch thorough planning aims to pro-duce. Companies such as GeneralMotors face a dilemma: the morethey attempt to define the process ofproduct development, the less theorganization is able to carry out that

process properly.Toyota, by contrast, has success-

fully standardized much of its devel-opment process. Product-engineer-ing departments follow highlyconsistent processes for developingsubsystems within a vehicle. Rou-tine work procedures– such as designblueprints, A3 reports, and feedbackforms for design reviews – are alsohighly standardized. The overallprocess of developing a vehicle fol-lows regular milestones. Indeed, thesuppliers we visited in Japan could

describe from memory Toyota’s ve-hicle-development process becauseit is so consistent from model tomodel. Every model has a concept,styling approval, one or two proto-type vehicles, two trial productionruns, and finally a launch; and sup-pliers know the approximate timingof each event. (For more on how Toy-ota uses standards to coordinate itswork with suppliers, see “A SecondLook at Japanese Product Develop-ment,” by Rajan R. Kamath andJeffrey K. Liker, HBR November–

December 1994.)Twist #1: How does Toyota avoid

the pitfalls that other companieshave experienced with work stan-dards? When you talk specifics withToyota engineers – such as howmany prototypes are built and tested,when designs are finalized, or howlong a particular phase takes – the re-sponse is typically that it varies caseby case. The actual standardizedwork plans are kept to a minimum;they often fit on a single sheet ofpaper. The basic process in the eyes

of the participants is very consistentfrom model to model, but the imple-mentation of the concept is indi-vidually designed for each vehicleprogram. Intense socialization of en-gineers through on-the-job trainingcreates a deep understanding ofevery step, as well as a broad under-standing of the expectations at mile-stones and final deadlines. Thesimplified plans allow flexibility,

8 harvard business review July–August 1998

how toyota integrates product developmentI D E A S A T W O R K

To prevent the chimney effect ’s

political conflicts, engineers

at the bucho level are regularly

rotated to areas outside their

expertise.

8/10/2019 Another Look at Toyota Product Development

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/another-look-at-toyota-product-development 9/12

8/10/2019 Another Look at Toyota Product Development

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/another-look-at-toyota-product-development 10/12

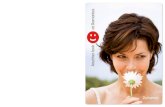

How the Coordinating MechanismsWork Together

C o n t i n u o u s, o

v e r l a p p i n g p r o

d u c t c y c l e sS t ab l e , l o n g - t e r m e m p l o y m e n t

keep standards fresh. The company

launches new vehicles on a regularbasis, several times every year. It al-so has annual product renewals, anda major model change every three tofour years, unlike other companiesthat stretch out their product cycles.Accordingly, standards are revisitedevery couple of months (as opposedto being used once and then putaway for a couple of years); they nev-er become outdated. The frequent

changes to the checklists also give

engineers continual opportunities todevelop and hone their skills.

Managing ProductDevelopment as a SystemTogether, these six mechanismsmake up a whole system, each partsupporting the others. Mentoringsupervision serves mainly to buildfunctional expertise, but it alsoteaches young engineers how to

write and interpret reports, work

with chief engineers, and under-stand and use standards. The chiefengineer’s prestige reinforces theimportance of expertise while it alsobalances out the functional bent ofthe other engineers. The chief engi-neer also promotes mutual adjust-ment by providing the working in-structions for each vehicle programand by resolving cross-functionaldisagreements.

10 harvard business review July–August 1998

how toyota integrates product developmentI D E A S A T W O R K

Stability and Power

The functional organization, with its intensive mentoring,

trains and socializes engineers in ways that foster in-depthtechnical knowledge and efficient communication.

Three types of standards interact and support one another

to improve the speed of development while allowingflexibility and building the company’s base of knowledge.

Levels of StandardizationIntegrative Social Processes

Standard Skills

intensive mentorship

local rotation

broad rotation athigher levels

StandardizedWork Processes

consistent butminimal processes

standards maintainedby departments

Design Standards

voluminouschecklists

livingdocuments

Integrative Leadership

chief engineer aslead designer

Mutual Adjustment

mix of writtencommunication and

meetings

long-term socializationand development

Direct Supervision

working engineers

mentoringsupervisors

Customer Focus

8/10/2019 Another Look at Toyota Product Development

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/another-look-at-toyota-product-development 11/12

For their part, the three types ofstandards interact and support oneanother to boost the pace of develop-ment; at the same time, they allowflexibility and build Toyota’s base ofknowledge. Without the othermechanisms providing reinforce-ment, each mechanism would notbe nearly as effective. (See the exhibit“How the Coordinating Mecha-

nisms Work Together.”)Indeed, the two halves of Toyota’s

system – social processes and stan-dards – interact in powerful ways.The functional organization, withits intensive mentoring, trains andsocializes engineers in ways that fos-ter in-depth technical knowledgeand efficient communication. With-out deep tacit knowledge about how

to develop products, standardizationwould become a bureaucratic night-mare. In turn, the common use ofthe different standards makes allfunctions automatically aware ofthe constraints imposed by interfac-ing groups and gives focus to reports

and meetings. Toyota shows thatcompanies do not need to choose be-tween functional depth and cross-functional coordination – each canfacilitate the other within the rightenvironment.

Toyota’s balanced approach alsobenefits from basic company poli-cies that provide a foundation for thewhole system. With a stable andlong-term workforce, the companycan afford to invest heavily in train-ing and socializing its engineers; itknows that the investment will pay

off for many years. The companyalso places great emphasis on satis-fying customers. Most of its engi-neers in Japan, for example, are re-quired to sell cars door to door for afew weeks in their first year of hire.Both factors help discourage thefunctional loyalties that might other-wise afflict a company with Toyota’sstructure.

These synergistic interactionsgive Toyota’s system its stabilityand power. They enable the auto-maker to integrate across projects as

well as within them. Design stan-dards, for example, facilitate integra-tion across functions while promot-ing the use of common componentsin simultaneous projects, and pro-vide a ready base of knowledge forthe next generation of products.

Implications for OtherCompaniesToyota’s mix of practices may not beright for other industries, or even forother companies in the auto indus-try. Different environments, differ-

ent corporate cultures, and differentcircumstances mean that a com-pany’s product-development systemmust be uniquely designed to suit itsdistinct needs. Indeed, Toyota’s sys-tem is not necessarily perfect evenfor Toyota. Although the companyhas succeeded mightily with its newproducts in mass-market sedans andluxury cars – two well-defined seg-ments of the marketplace– it has re-

harvard business review July–August 1998 11

how toyota integrates product development I D E A S A T W O R K

Little face-to-face

contact.

Predominantly

written

communication.

Close supervision

of engineers by

managers.

Large barriers

between functions.

No system design

leader.

No rotation of

engineers.

New development

process with everyvehicle.

Complex forms

and bureaucratic

procedures.

Obsolete, rigid

design standards.

Reliance on meetings

to accomplish tasks.

Predominantly oral

communication.

Little supervision

of engineers.

Weak functional

expertise.

System design

dispersed among

team members.

Rotation at rapid

and broad intervals.

Lengthy, detailed,

rigid developmentschedules.

Making up

procedures on

each project.

No design standards.

Succinct written reports for

most communication.

Meetings for intensive problem

solving.

Technically astute functional

supervisors who mentor, train,

and develop their engineers.

Strong functions that are

evaluated based on overall

system performance.

Project leader as system

designer, with limitations on

authority.

Rotation on intervals that are

longer than the typical product

cycle, and only to positions that

complement the engineers’

expertise.

Standard milestones–project

leader decides timing, functionsfill in details.

Standard forms and procedures

that are simple, devised by the

people who use them, and

updated as needed.

Standards that are maintained

by the people doing the work

and that keep pace with current

company capabilities.

How Toyota Avoids Extremes

Mutual Adjustment

Design Standards

Standard Work Processes

Direct Supervision

Integrative Leadership

Standard Skills

CHIMNEY EXTREME TOYOTA BALANCE COMMITTEE EXTREME

8/10/2019 Another Look at Toyota Product Development

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/another-look-at-toyota-product-development 12/12

are not panaceas, and they do havesignificant drawbacks. One mustweigh the benefits and drawbacks ofa particular practice, including howit contributes to all aspects of inte-gration (including integration acrossprojects) and how it affects other

parts of the system.Finally, the success of Toyota’s

system rides squarely on the shoul-ders of its people. Successful productdevelopment requires highly compe-tent, highly skilled people with a lotof hands-on experience, deep techni-cal knowledge, and an eye for theoverall system. When we look at allthe things that Toyota does well, wefind two foundations of its product-development system: chief engi-neers using their expertise to gainleadership, and functional engineers

using their expertise to reduce theamount of communication, supervi-sion, trial and error, and confusion inthe process. All the other coordinat-ing mechanisms and practices serveto help highly skilled designers dotheir job effectively. By contrast,many other companies seem to as-pire to develop systems “designed bygeniuses to be run by idiots.” Toyotaprefers to develop and rely on theskill of its personnel, and it shapesits product-development processaround this central idea: people, not

systems, design cars.

Reprint 98409

To place an order, call 1-800-988-0886.

acted late to the recent major shiftsin consumer demand: first to mini-vans and then to sport-utility vehi-cles. So design standards and inter-nal socialization, for example, maymake for nimble and innovativeproduct development, but perhaps at

the cost of discouraging some bigleaps in thinking.

Nevertheless, we believe thatToyota’s system has important im-plications for other companies. First,integrated product-developmentprocesses should be developed andimplemented as coherent systems.Individual best practices and toolsare helpful, but their potential canbe fully realized only if they are inte-grated into and reinforce the overallsystem. Toyota was fortunate in thatit was able to develop its system

over decades through an incremen-tal, almost unconscious, process oftaking good ideas and adapting themto the existing structure. Other com-panies that conclude they are goingdown the wrong track and need amajor overhaul of their product-development systems do not havethe luxury of developing their sys-tem gradually over time. They willneed to be much more conscious ofdesigning a coherent system.

Second, well-designed systemsshould balance the demands of func-

tional expertise and cross-functionalcoordination. The chart “How Toy-ota Avoids Extremes” describes fea-tures of the two opposing sides: thechimney extreme, characterized by

strong functional divisions, and thecommittee extreme, characterizedby broad-based decision making andweak functional expertise. Toyota,for example, uses both written formsof communication and face-to-facecontact to the extent that each is

useful and efficient.Achieving the proper balance,

however, is no easy task. Many ofToyota’s current practices– such asan emphasis on written communica-tion, design standards, and the chiefengineer – seem to have been stan-dard practice in the United States inthe 1950s and earlier. But in the1960s and 1970s, as U.S. automakersneglected their developmentprocesses, systems that were oncesound and innovative gave way tobureaucracy, internal distrust, and

other distractions that brought thecompanies close to the chimney ex-treme. In reaction, those companiesseem to have swung toward the otherend of the spectrum. Results in theshort term have been encouraging,but the deficiencies of the commit-tee extreme may well appear soon.Some companies are discoveringthem already.

The key is to strike the appropri-ate balance for one’s situation. Itmay be perfectly appropriate insome circumstances to rely almost

solely on meetings for communica-tion and problem solving or to aban-don standard procedures completely.But such practices are not good forall organizations at all times. They

12 harvard business review July–August 1998

how toyota integrates product developmentI D E A S A T W O R K