annsurg01228-0005

Transcript of annsurg01228-0005

ANNALS OF SURGERYOctober 1958

Inguinal and Femoral Hernioplasty *The Evaluation of a Basic Concept

C. B. MCVAY, M.D., PH.D.,** JoHN D. CHAPP, M.D., M.S.f

IntroductionTHIs woRK began as a study of the nor-

mal anatomy of the inguino-femoral regionbecause of conflicting descriptions of thetransversalis fascia, the falx inguinalis andother structures in this region. Originallythere was no thought of the hernia problembut as the study continued over a four yearperiod and the examination of over 500inguino-femoral regions, the implicationsbecame obvious. This original work, be-tween the years 1934 and 1938, was carriedout by the senior author under the direc-tion of, and in association with, Doctor B.J. Anson, Professor of Anatomy, Northwest-ern University Medical School.The detailed results of these studies have

been recorded 1, 2, 25, 26 and only such fea-tures will be outlined here as are necessaryto orient the reader of this paper. Thetransversalis fascia is simply the innermostmuscle fascia of the transversus abdominismuscle. Where the layer is muscular, as atthe abdominal inguinal ring, it is easily'

* Presented before the American Surgical Asso-ciation, New York, N. Y., April 16-18, 1958.

** Clinical Prof. of Surgery and Assoc. Prof.of Anatomy, Univ. of South Dakota School ofMedical Sciences. Surgeon, The Yankton Clinic.

f Senior Resident in Surgery, University ofKansas Medical Center. Formerly Resident in Sur-gery, Yankton Clinic and Univ. of South DakotaSchool of Medical Sciences.

separable as a definite layer; but where itis aponeurotic, the fascia becomes fusedwith the aponeurotic fibers to form a singlelayer. In the inguinal region and behindthe spermatic cord we refer to this layer asthe posterior inguinal wall (Fig. 1). It isupon the variable strength and distributionof this layer that direct ingunial and fem-oral hernias are dependent for their devel-opment. The patient in whom the aponeu-rotic fibers are sparse is the one likely todevelop a direct inguinal hernia becausethe posterior inguinal wall is weak. Thepatient with a narrow insertion of the pos-terior inguinal wall into Cooper's ligamentis the one likely to develop a femoral herniabecause this leaves a broadened femoralring.

Since the posterior inguinal wall insertsinto Cooper's ligament (ligamentum pub-bicum superius) and has only a contiguousrelationship to the inguinal ligament, wehave always maintained that the repair ofthe groin hernias that compromise the pos-terior inguinal wall (large indirect, directand femoral hernias) should use Cooper'sligament in the hernia repair and not theinguinal ligament. The details of our "Re-construction of the Posterior Inguinal Wallrare readily available 27-32 and wiU not berepeated in this paper since this is a statis-tical evaluation of the method. However,

499

Vol. 148 No. 4

McVAY AND CHAPP Annals of SurgeryOctober 1958

MNobl.int.Apon.xni.transv. abd.

|'

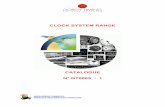

FIG. 1. The anatomy of the transversus abdominis muscle and aponeurosis in theinguinal region. Note that the anterior femoral sheath is a continuation of the trans-versalis fascia; also, that the excised inguinal ligament is not part of the all importantposterior inguinal wall (transversus abdominis aponeurosis). (From McVay andAnson: Anat. Rec., 76:213, 1940.25)

for ready reference, the completed "Recon-struction of the Posterior Inguinal Wall" isshown in (Fig. 2).The development of the small indirect

inguinal hernia, congenital in origin, is de-pendent upon the protrusion of a viscusinto a persistent processus vaginalis. Thecrux of the small indirect inguinal herniaproblem is the size of the abdominal in-guinal ring and not the length or size ofthe peritoneal sac. Most of these herniasneed no more than high ligation and exci-sion of the hernial sac with a closure of thefascial abdominal inguinal ring to normalsize. The closure of the abdominal inguinal

ring may take one or several sutures, de-pending upon the size to which it has beendilated by the hernia. The closure, our

"Abdominal Ring Repair," is accomplishedmedial to the cord structures by suturingthe transversalis fascia above to the anteriorlayer of the femoral sheath below (Fig. 3).Again, the inguinal ligament is not utilizedbecause it is a more superficial structureand not part of the normal continuity ofthis layer. The lateral part of the inguinalregion, in which the abdominal inguinalring is located, lies over the external iliacvessels; and distally where the muscularfibers of the transversus abdominis termi-

500

INGUINAL AND FEMORAL HERNIOPLASTY

raidlalis M.

~~~~Aq\W~~~~~~V¾~~

FIG. 2. Reconstruction of the posterior inguinal wall. 1. Rectus sheath sutured toCooper's ligament. 2. Transition suture. 3. Transversalis fascia sutured to anteriorfemoral sheath. (From Hernia, by C. B. McVay, Courtesy of Charles C Thomas,Publisher, Springfield, Illinois.)

nate, the transversalis fascia continues intothe thigh as the anterior layer of the fem-oral sheath (Fig. 1). It is the re-establish-ment of this fascial continuity to make asnug abdominal inguinal ring that consti-tutes the repair of the small indirect in-guinal hernia and nothing more.31' 32

In this series of 580 hernioplasties, theinguinal (Poupart's) ligament was not usedin a single instance. In all of them thespermatic cord was replaced in its normalposition and the external oblique aponeuro-sis closed over the cord so that a snug sub-cutaneous inguinal ring was formed in thenormal position, just lateral to the pubictubercle. The inguinal ligament thus re-

tains its sole purpose, that of a sling andsupport for the contents of the inguinalcanal. Many years ago, Gallaudet 1 t stated,"The inguinal ligament is a free margin"and this simple anatomic fact can be dem-onstrated at the operating table by a mo-ment of gentle dissection with the handleof the knife. The medial end of the inguinal

ligament, known as the lacunar (Gimber-naut's) ligament, also attaches to Cooper'sligament. The lateral one-fourth of the in-guinal ligament is not free by virtue ofsome of the fibers of the external obliqueaponeurosis passing caudally into the fascialata. However, in the region of hernia re-

pair, the inguinal ligament is indeed a freemargin as stated by Gallaudet. The in-guinal ligament has a slightly convex infe-rior margin and is held in this position bythe fascial layer in which it is imbedded-the fascia lata. The fascial coverings of theexternal oblique aponeurosis (innominatefascia of Gallaudet) are continuous withthe fascia lata.

Finally, we consider the femoral herniato be simply a third variety of inguinalhernia. Irrespective of the femoral locationof the hernial sac, the origin of this herniais as truly inguinal as the other two groinhernias. No matter what one considers theinitial etiology of the femoral hernia to be,the end result is a wide femoral ring and a

Volume 148Number 4 501

I

502 McVAY AND CHAPP

FIG. 3. Abdominal inguinal ring repair. (FromHernia, by C. B. McVay, Courtesy of Charles CThomas, Publisher, Springfield, Illinois.)

narrowed insertion of the posterior inguinalwall into Cooper's ligament. The proper

approach to the repair of this hernia is

through the inguinal region and consistsvery simply (after disposing of the hernialsac) of broadening the posterior wall at-tachment into Cooper's ligament so thatthe femoral ring is obliterated.I1 32

For the purpose of emphasis it is worth-while to restate the premises upon whichwe base our repairs of the groin hernias.For the small to medium size indirect in-guinal hernias we do nothing more thanexcise the hernial sac and tighten the ab-dominal inguinal ring to normal by sutur-ing the transversalis fascia to the anteriorlayer of the femoral sheath, medial to thecord (Fig. 3). For large indirect inguinal,direct inguinal, and femoral hernias we re-

construct a new posterior inguinal wall.Briefly, this consists of excising all atten-uated aponeurotico-fascial structures, therelaxing incision, and a "slide" of the rectussheath into the position of a new posterioringuinal wall. This new posterior wall issutured to Cooper's ligament as far laterallyas the femoral vein and after the transitionsuture,31 ,32 the transversalis fascia is su-

tured to the anterior layer of the femoralsheath far enough laterally to make a snug

abdominal inguinal ring (Fig. 2). In bothrepairs the spermatic cord is replaced in itsnormal position and the external obliqueaponeurosis closed to make a snug sub-

Annals of SurgeryOctober 1958

cutaneous inguinal ring in the normal posi-tion.

In previous publications we have ac-knowledged the many significant contribu-tions to the subject of groin hernioplastyand so this lengthy subject will be omittedin this paper. However, we would be re-miss not to again acknowledge the paperof Lotheissen,23 who first used Cooper'sligament in inguinal and femoral hernio-plasty, and Dickson,7 who used Cooper'sligament for femoral hernioplasty.

Hernia RecurrencesThe repoited incidence of recurrence in

many series of hernia operations forms abulky contribution to the medical litera-ture of the past half century. Although thestated incidence of recurrence shows con-siderable variation through the years, mostauthors are agreed that it is the direct in-guinal and the large indirect inguinal her-nias that form the bulk of the recurrences.Some reports also show a high rate of re-currence following femoral hernioplasty.Because many of the earlier series lumpedall inguinal hernias together, it was difficultto arrive at the true picture of the recur-rence rate. Since in all series, the small in-direct inguinal hernia comprises roughly60 per cent of the total and since successattends almost any operation for this sim-plest of the groin hernias, a very favorablerecurrence rate in this group may concealan appalling recurrence rate for the directand the large indirect inguinal hernias.This grouping of the indirect and direct in-guinal hernias is not surprising since inmany series essentially the same operationis used, irrespective of the type of hernia,although more elaborate re-enforcementmethods may be used such as imbricationof layers, or the use of fascial sutures andgrafts.The many articles dealing with recur-

rence rates are difficult to compare. In gen-eral, most surgeons report very favorableresults in the small indirect inguinal hernia,irrespective of the operation used; andmost agree that the direct inguinal hernia

INGUINAL AND FEMORAL HERNIOPLASTY

carries the highest recurrence rate. In thelatter group the opinion varies from that ofAndrews and Bissel 3 to this present report.Andrews and Bissel felt that the recurrencerate was so high in the direct inguinal her-nia that operation should not be attempted.A fair average of the reported series wouldbe a figure of 20 per cent recurrence foroperations on direct inguinal hernia. Somereports list recurrence after femoral hernio-plasty to be just as high. A recent articleby Telle 40 divides the hernias into theirrespective categories in considering the re-currence rates. Table 2 in this article byTelle demonstrates the high recurrence ratein the direct inguinal hernia using technicsthat do not utilize Cooper's ligament. Inrecent years it would appear that there hasbeen a general change to the use of Coop-er's ligament in the repair of the difficultgroin hernias.Koontz 22 analyzed a questionnaire sent

to 286 eminent surgeons and while most ofthem reported that they still use an inguinalligament type of hernioplasty for the aver-age inguinal hernia, there were a significantnumber who used Cooper's ligament in thedifficult hernias. This is in sharp contrast tothe opinion prior to 1940. The reported re-sults of Burton,4 Clark and Hashimoto,5Farris,'" Ferguson,'2 Harkins,'6-19 Hollo-way,20 Matson,24 McVay,27-30 Rice andStrickler,35 Sanderson and Rice,38 Telle,40and others would appear to more thanjustify the adoption of this very fundamen-tal anatomic technic in all groin herniasthat compromise the posterior inguinalwall.

Fallis,8 Telle,40 and Clear 6 emphasizethe importance of a long term follow up,and in this we certainly concur. When the

TABLE 1. All Groin Hernias, 1946-1956

Type of Hernia Number Per cent

Indirect inguinal, all sizes,including combined hernias 467 80

Direct inguinal 74 14Femoral 39 6

Total 580 100

TABLE 2. Single, Recurrent and Combined Hernias

Primary single hernias 498Recurrent hernias 45Indirect-direct hernias 21Indirect-femoral hernias 9Indirect-direct-femoral hernias 7

Total hernias 580

recurrence is as a direct inguinal herniafollowing the repair of a small indirect in-guinal hernia, it may not become apparentfor many years. On the other hand, whenthe recurrence is due to a missed hernia,the recurrence time is short (Table 5).From the published reports, including thematerial in this paper, it would appear thata ten year follow up should be the stand-ard. Any longer period would probably notbe practical since death and the gradualdecrease of follow up percentages wouldoffset the value of a longer period.

This paper is essentially the report oftwo series since we have maintained, alongwith Potts 34 and others,"1 37, 41 that in thesimple small indirect inguinal hernia, littlemore need be done than to adequately re-

move the hernial sac. However, even in in-fants we suture the transversalis fascia tothe anterior layer of the femoral sheath,medial to the cord, so as to snuggly closethe abdominal inguinal ring. In the indirectinguinal hernia that has enlarged the ab-dominal inguinal ring medially beyond thesagittal position of the medial margin ofthe femoral ring, we change to the opera-

tion of "Reconstruction of a New PosteriorInguinal Wall," in the same manner thatwe repair a direct inguinal hernia. There-fore, in reporting this series of 580 hernio-plasties, 344 are "Abdominal Ring Repair"for small indirect inguinal hernias and 236are "Reconstruction of the Posterior In-guinal Wall" for the larger indirect in-ginal, direct inguinal and femoral hernias(Table 3).This group of 580 hernias were operated

upon on the senior author's service duringthe 11 year period from 1946 to 1956 in-clusive. While the majority of these hernio-

Volume 148Number 4 503

504 McVAY AND CHAPP

plasties were performed by two staff men,all interns and residents rotating throughthe service did a good share of the herniaoperations after careful supervision in theirearlier cases. It is interesting that all butfour of the recurrences were in cases oper-ated upon by the senior author. It is anatural consequence of our long interestin this subject that we never let the internor new resident perform his first hernia op-eration until he is thoroughly conversantwith the normal anatomy; and he is thensupervised as mentioned above. This is insharp contrast to the practice in years goneby where a hernia operation was consid-ered to be such a simple problem that itwas the first operation that an intern per-formed with very little instruction or super-vision. We have found that the properevaluation of the hernia problem at the op-erating table takes considerable judgmentand experience and, as will be seen shortly,it is the error in judgment that accounts formost of our recurrences. Furthermore, notall hernia operations are easy or technicallysimple. Obesity usually makes a hernia op-eration difficult; and most recurrent herniasare difficult and time consuming operationsbecause of the cicatricial fusion of all layers.The follow up in this series is 91 per cent

with the examination period varying fromone to eleven years after operation. Table 1shows the numbers and percentages of thethree grion hernias repaired and Table 2

TABLE 3. Operations for Groin Hernias

Type of Type of No. of % ofOperation Hernia Cases Total

Abdominal ring Small to medium 344 59.3repair indirect

inguinal hernia

Reconstruction Large indirect 123posterior (includinginguinal wall combined(Cooper's liga- hernias)ment)

Direct 74Femoral 39

236 40.7

Annals of SurgeryOctober 1958

TABLE 4. Recurrences. 580 Hernioplasties

No. of Recur- PerHernias rences Cent

Total hernioplasties 580 13 2.24(1946-1956)

Abdominal ring repair 344 11 3.2Reconstruction posterioringuinal wall(Cooper's ligament) 236 2 0.85

No recurrences in 39 reconstructions of posterioringuinal wall for femoral hemia.

shows the number of primary, recurrentand combined hernias repaired. A weak-ness or slight bulging of the posterior in-guinal wall discovered at the time of opera-tion for an indirect inguinal hernia was afairly common occurrence and, althoughthe posterior inguinal wall was recon-structed, these have not been listed as com-bined or pantaloom hernias in this series.The 21 hernias listed as indirect-direct inTable 2 were true double sac hernias. Like-wise, direct inguinal hernias with an in-cidentally discovered small indirect sac arelisted only as direct hernias.

Table 3 shows the types of hernias, theirnumbers and the per cent of the total seriesrepaired by "Abdominal Ring Repair" and"Reconstruction of the Posterior InguinalWall." Thus, in well over one-half of the580 hernioplasties performed in this series,nothing more was done than high ligationof the indirect hernial sac and tightening ofthe abdominal inguinal ring. A specialpoint is made of this since the seniorauthor has been quoted frequently as do-ing a "Cooper's Ligament" repair on allhernias. In spite of the fact that 11 of our13 recurrences have been in this group ofsimple repairs, we do not feel that the morelengthy and difficult Reconstruction Opera-tion should be done on all hernias. Al-though one might infer from our results,Table 4, that this should be done, we haveadhered to strict criteria for doing the "Re-construction" operation.28 30 Rather, wewould emphasize the importance of thejudgment necessary to properly evaluatethe indications at the operating table.31

Volume 148Number 4 505INGUINAL AND FEMORAL HERNIOPLASTY

TABLE 5. Details of Recurrences. 91% Follow up. 1-11 Years

YearsType of ] Follow up

Age, Hernia Type of Recurred Time of Cause of Second WithoutCase Sex Years Type Repair as Recurrence Recurrence Repair Recurrence

1 M 19 I A.R. I 6 years Technic A.R. 3 years2 M 76 I A.R. I 3 years Technic A.R. 2 years3 M 32 I A.R. I 3 years Technic A.R. 2 years4 M 60 I A.R. I 32 months Technic R.P.W. 8 years5 M 54 D &I R.P.W. D 4 years Technic R.P.W. 2 years6 M 57 I A.R. D &I 6.5 years Technic and R.P.W. 4 years

judgment7 M 55 I A.R. D 7 years Judgment R.P.W. 2 years8 M 18 I A.R. D 6 years Judgment Not yet operated upon9 M 62 D R.P.W. D & I 9 months Infection R.P.W. 9 years10 F 41 I A.R. F 6 months Missed R.P.W. 4 years11} MB 1.5 I A.R. F 9 months Missed R.P.W. 6 years12J Bilateral l I A.R. F 16 months Missed R.P.W. 4 years13 F 41 I A.R. F 3 weeks Missed R.P.W. 6 years

Legend: I-Indirect. D-Direct. A.R.-Abdominalinguinal wall.

Table 5 is a statistical evaluation of ourrecurrences and is largely self-explanatoryalthough some elaboration is pertinent.When an identical hernia recurred this isreferred to as an error in technic, e.g.cases 1-6 were essentially recurrences ofthe original hernia. In four instances, cases1, 2, 3 and 4, the small indirect inguinalhernia recurred as a small indirect inguinalhernia. In two instances, no exact causecould be determined except that the ab-dominal inguinal ring must not have beentightly enough closed. In the other twocases, one right and the other left, bowelmust have been caught in the closure ofthe hernial sac. The left-sided recurrencehad an epiploic appendage of the sigmoidcolon as the entering wedge of the hernialsac. On the right, the small sac was prin-cipally a sliding hernia of the cecum andwe presume that the cecum must have beencaught and fixed in the closure of the ab-dominal ring.

Cases 6, 7 and 8 are listed as errors injudgment since a small indirect inguinalhernia recurred as a direct inguinal hernia.In other words the posterior inguinal wallgave out in time and this weakness shouldpossibly have been recognized at the timeof the first operation. It is significant that in

ring repair. R.P.W.-Reconstruction of the posterior

this group it took six years or more for therecurrence to become manifest. In re-read-ing the operative notes on these three casesthere was no mention of suggestive weak-ness of the posterior inguinal wall. On theother hand it is not uncommon to see atranslucent posterior wall in an elderly in-dividual with an indirect inguinal herniawho has not developed a direct inguinalhernia. Therefore, it is probably inevitablethat there will always be some of thesecases in every series.Case 9 represents a massive wound infec-

tion and the recurrence was evident in lessthan a year. There was one other seriouswound infection in a reconstruction of theposterior inguinal wall that has not devel-oped a recurrence to-date but only one andone-half years have elapsed. Minor sub-cutaneous wound infections have occurredin two per cent of this series. While case9 is listed as a second reconstruction of theposterior inguinal wall this is not strictlythe case. There were two discrete apertures1 cm. in diameter. The direct aperture wasjust above and lateral to the pubic tuberclein an otherwise intact and densely scarredposterior wall and was closed transverselywith four 32 gauge stainless steel wire su-tures. The other sac in this case was an in-

506 McVAY A

direct one and after excision of the sac, thescarred margins of the slightly dilated ab-dominal inguinal ring were approximatedmedial to the cord with wire sutures. It isnow over nine years since the secondaryoperation and there is no sign of recur-rence.

Cases 10-13 are listed as missed herniassince the femoral hernia appeared ratherpromptly after the repair of a simple smallindirect inguinal hernia. One cannot escapethe fact that the femoral hernia must havebeen present all the time and was simplynot recognized at the time of the originaloperation. During the reconstruction of theposterior inguinal wall for direct or largeindirect inguinal hernias, we have occa-sionally observed a protrusion of the pre-peritoneal fat through a slightly dilatedfemoral ring and without any suggestionof a peritoneal sac. It is likely that all fem-oral hernias begin with this entering wedgeof fat and this incipient phase should besearched for carefully. It should be notedthat cases 11 and 12 represent bilateral in-direct and femoral hernias in a male infant.Of further interest, we have subsequentlyrepaired a femoral hernia in this child'sthree year old sister and another sister nowage five has a femoral hernia. Had we beenastute enough to recognize the femoral her-nias in this one case our recurrence recordwould have been substantially better. Whilesome recurrences are inevitable, the missedhernia is a blunder and it does not takemany such mistakes to be catastrophic inany carefully guarded hernia series.Case 5, mentioned above as a technical

failure, is an interesting recurrence. A re-construction of the posterior inguinal wallhad been done for a direct-indirect in-guinal hernia. The recurrence was a diver-ticular type of direct inguinal hernia witha 12 mm. defect 1 cm. above and lateral tothe pubic tubercle. There was no peritonealsac but a protrusion of the urinary bladder,with surrounding preperitoneal fat, thatprotruded through the subcutaneous in-

D CHAPP Annals of SurgeryOctober 1958

guinal ring for a distance of 3 cm. Since theremainder of the posterior wall was strong,the defect was simply closed with inter-rupted silk sutures. The cause of this recur-rence is, of course, speculative but prob-ably represents injury to the posterior wallat the time of the original operation. An-other possibility is a missed defect. Wehave occasionally found a tiny protrusionof preperitoneal fat between the aponeu-rotic fibers of an otherwise intact andstrong posterior inguinal wall. Excision ofthe fatty protrusion after ligation of itspedicle and closure of the 1 or 2 mm. de-fect with a silk suture or two has sufficed.At least to date there have been no recur-rences in these cases.

Discussion

Since this presentation is the evaluationof the author's methods, comparative tableswith other studied series of recurrencesusing similar or other methods have notbeen presented. These are readily availablein the medical literature and, furthermore,it is difficult to compare the various series.Time is an important element in the in-cidence of recurrence and unless two com-parable series each had all their cases fol-lowed for the same length of time, they arenot comparable. We are aware that ourstatistics will change from time to time andthat if all of our cases had been followedfor 11 years we would undoubtedly showa higher recurrence rate in all categories.If we had omitted our four cases of missedfemoral hernias, the recurrence rate in theabdominal inguinal ring repair group wouldhave been 2 per cent instead of 3.2 percent. Some would argue that a direct in-guinal hernia that appears years after therepair of a simple indirect inguinal herniais a brand new hernia and not a recurrence.While this may be theoretically true, wefeel that these should be listed as recurrenthernias. In other words, a secondary or sub-sequent groin hernia must be listed as a re-

kN

INGUINAL AND FEMORAL HERNIOPLASTY

currence or any comparison of methods isimpossible.

Excellent results have been reported inthe small indirect hernia group with noth-ing more than high ligation of the peri-toneal sac 34 but we feel that any dilatationof the fascial abdominal inguinal ringshould be corrected, even in infants. Theprotrusion of preperitoneal fat through thedilated abdominal ring in the postoperativeperiod must surely be a basis for the de-velopment of a recurrent indirect inguinalhernia. It only takes a moment to place a

suture or two medial to the cord, approx-

imating the transversalis fascia to the ante-rior femoral sheath, and this restoration ofthe abdominal inguinal ring would seem tous to be a rational procedure. Koontz hasalso expressed this opinion in a discussionof the paper by Potts.34Following our experience with a bilateral

recurrence as femoral hernias in an infant(Table 5, cases 11 and 12) some seven

years ago we abandoned the very simpleapproach to the repair of the small indirecthernia in the infant and child as recom-

mended by Potts and others. We have sincetreated these more like adult hernias, al-though we do not disturb the cord beyondthe subcutaneous inguinal ring. In the in-fant it is not possible to insert a finger intothe peritoneal cavity for palpation of theinguinal region, we therefore rely entirelyupon inspection. The speramtic cord or

round ligament with attached cremastermuscle is carefully elevated from its bedby incising the very delicate cremaster fas-cia where internal oblique and cremastermuscle fibers join. This allows inspectionof the area of direct inguinal hernia and bygently retracting the inguinal ligament dis-tally, the base of the femoral canal can beadequately evaluated for the presence ofa femoral hernia. If this is carefully done,the posterior inguinal wall is not injuredand it only adds a few minutes to the op-

erating time. We have not found anotherfemoral hernia in an infant whom we have

operated upon for indirect inguinal herniabut we have found two cases of concomit-ant direct inguinal hernia. One might pointout that these are isolated instances, andthis is true, but it does not take many mis-takes to drastically affect one's recurrence

rate. In this series of 580 hernioplasties,sixty-two were in infants and all have beenfollowed. The two femoral hernias missed,make a recurrence rate of 3.2 per cent forthe infants. Had we missed the two withconcomitant direct inguinal hernias thenumber would be four and a recurrencerate of over 6 per cent, which would hardlybe acceptable.

In the two years prior to our change inpolicy for the evaluation of the infant her-nia, we were occasionally exploring the op-

posite side as recommended by Muellerand Rader.33 Since we started the moretime consuming exploration of the inguinalcanal in the infant we have abandoned the

simultaneous exploration of the oppositeside. While it is true that bilateral persist-ence of the processus vaginalis is common,many of these sacs are small and never re-

ceive a viscus to become a detectable her-nia. In a personal communication, DoctorAnson informs me that in 100 consecutivecadavers examined, 20 per cent had a rem-

nant of the processus vaginalis but no her-nia. In our entire series, 12 per cent hadbilateral hernias repaired. Additive to thiswere 6 per cent who had had a previous her-nia operation on the opposite side, or whosubsequently returned to have a hernia re-

pair on the opposite side. This makes a totalover-all incidence of bilaterality of 18 per

cent. It is possible that many of the in-cipient sacs discovered by exploring theopposite side in infants and children wouldnever develop into a true hernia.Our results of reconstruction of the pos-

terior inguinal wall in the difficult hernias(large indirect, direct and femoral) speakfor themselves and need not be commentedupon further except to say that we considerthis operation a restoration of normal in-

Volume 148Number 4 507

508 McVAY AND CHAPP

guinal anatomy. With the exception offemoral hernioplasty, all reconstructions ofthe posterior inguinal wall must include therelaxing incision (Haisted 14) to permit the"slide" (Tanner 39 ). The importance of arelaxing incision and the use of the rectussheath has also been recognized by Fallis,9Rienhoff 36 and Farris.10 The relaxing inci-sion permits the shift of rectus sheath intothe position of a new posterior inguinalwall and the suture of this wall to Cooper'sligament without tension. We also believein replacing the cord in its normal positionso that the obliquity of the inguinal canalis restored. In all but three of our re-current hernias, with the original herniaoperation performed elsewhere, we foundthe cord in the subcutaneous or Halsted Iposition.We have not seen a hernia or even a

weakness develop in the rectus sheath de-fect left by the relaxing incision. The rectusand pyramidalis muscles with their invest-ing fascia, which is a medial continuationof the transversalis fascia, plus the overly-ing external oblique aponeurosis, wouldappear to be a very adequate bulwarkagainst herniation.We have never used fascial sutures, fas-

cial grafts or skin as a patch in the repairof a groin hernia. On four occasions whenthe relaxing incision and slide would notwork because of anatomic anomalies, wehave used stainless steel wire mesh as partof the repair in a manner similar to thatdescribed by Koontz.2' In all primary her-nias and most recurrent hernias, the rectussheath in the vicinity of the relaxing inci-sion is virgin territory and the slide is ac-complished with ease. It is for this reasonthat we feel that prostheses are unneces-sary in the great majority of inguinal herniaoperations.We have been able to follow all of our

cases in whom we have repaired a recur-rent hernia and none of these has had asubsequent recurrence. Of the 45 recurrenthernias repaired, 30 were a first recurrence,

Annals of SurgeryOctober 1958

ten had a second recurrence, four had athird recurrence and one had had four re-currences.

In the entire group, one had been in-jected with paraffin years before and, inaddition to his hernia, had enormous paraf-finomas. Twelve cases in the whole serieshad previously had a sclerosing solution in-jected. For the uninitiated it is worth men-tioning that the patient who has previouslyhad the injection treatment may present amost difficult problem. The dense fusion ofall layers, including the elements of thespermatic cord, makes for a time consum-ing, bloody and difficult hernia repair.The mortality in this series of 580 hernio-

plasties was 0.5 per cent. Two of the threecases were due to pulmonary embolism:one, age 70, in 1947 and the other, age 65,in 1948. The third death w\vas in a moribund87-year-old man, in 1952, with an incarcer-ated femoral hernia. He survived the op-eration under local anesthesia nicely butsuccumbed on the fourth postoperative dayfrom uremia and congestive heart failure.When indicated we have not refused a

patient a hernia operation because ofchronologic age, and many of our patientshave been elderly and operated upon underlocal anesthesia. A hernia operation canbe performed under local infiltration andregional block anesthesia comfortably andwith very minimal risk. This is certainlypreferable to procrastination when the her-nia is incapacitating or there is a history ofincarceration.

Summary

(1) A one to 11-year-follow up on 580hernioplasties utilizing the methods previ-ously described by the senior author hasbeen presented. The recurrences have beenitemized and analyzed. The follow up is 91per cent.

(2) The results in 236 reconstructions ofthe posterior inguinal wall for difficult her-nias are significant. A recurrence rate of0.85 per cent.

Volume 148 INGUINAL AND FEMORAL HERNIOPLASTY 509

Number 450(3) The less dramatic results in 344 ab-

domianl inguinal ring repairs for the simpleindirect inguinal hernia (recurrence rate of3.2%) point out the importance of highligation of the sac with tight closure of theabdominal inguinal ring; the experienceand judgment necessary to properly evalu-ate the posterior inguinal wall; and the sig-nificance of the missed femoral hernia.

(4) The inguinal ligament was not usedin any of the hernioplasties in this series.

(5) The relaxing incision should alwaysbe used in reconstruction of the posterioringuinal wall, femoral hernioplasties usu-ally excepted.

Bibliography1. Anson, B. J. and C. B. McVay: The Anatomy

of the Inguinal and Hypogastric Regionsof the Abdominal Wall. Anat. Rec., 70:211,1938.

2. Idem: The Anatomy of the Inguinal Region.Surg., Gynec. & Obst., 66:186, 1938.

3. Andrews, E. and A. D. Bissel: Direct Hernia:A Record of Surgical Failures. Surg., Gynec.& Obst., 58:753, 1934.

4. Burton, C. C.: The Critical Point of Cooper'sLigament Hernia Repair. Am. J. Surg., 91:215, 1956.

5. Clark, J. H. and E. I. Hashimoto: Utilizationof Henle's Ligament, Iliopubic Tract, Apo-neurosis Transversus Abdominis and Coop-er's Ligament in Inguinal Herniorrhaphy.Surg., Gynec. & Obst., 82:480, 1946.

6. Clear, J. J.: Ten Year Statistical Study of In-guinal Hernias. Arch. Surg., 62:70, 1951.

7. Dickson, A. R.: Femoral Hernia. Surg., Gynec.& Obst., 63:665, 1936.

8. Fallis, L. S.: Inguinal Hernia: A Report of1,600 Operations. Ann. Surg., 104:403, 1936.

9. Idem: Direct Inguinal Hernia. Ann. Surg.,107:572, 1938.

10. Farris, J. M., J. Eittinger and J. A. Weinberg:Hernia Problem with Reference to Modifica-tion of the McVay Technique. Surgery, 24:293, 1948.

11. Ferguson, A. H.: Oblique Inguinal Hernia:Typic Operation for Its Radical Cure. J. A.M. A., 33:6, 1899.

12. Ferguson, D. J.: Recurrence Following In-guinal and Femoral Hernia Operations.Minn. Med., 32:697, 1949.

13. Gallaudet, B. B.: A Description of the Planesof Fascia of the Human Body. New York,Columbia Univ. Press, 1931.

14. Halsted, W. S.: The Cure of the More Difficultas Well as the Simpler Inguinal Ruptures.Bull. Johns Hopkins Hosp., 14:208, 1903.

15. Harkins, H. N.: A Cooper's Ligament Herniot-omy: Clinical Experience in 322 ConsecutiveCases. Surg. Clin. North Am., 23:1279, 1943.

16. Idem: The Repair of Groin Hernias: Progressin the Past Decade. Surg. Clin. North Am.,29:1457, 1949.

17. Idem: Recent Advances in the Treatment ofHernia. Ann. West. Med. & Surg., 6:221,1952.

18. Harkins, H. N., D. E. Szilagyi, B. E. Brushand F. R. Williams: Clinical Experienceswith the McVay Herniotomy. Surgery, 12:364, 1942.

19. Harkins, H. N. and R. H. Schug: Hernial Re-pair Using Cooper's Ligament: Follow-upStudies on 367 Operations. Arch. Surg., 55:689, 1947.

20. Holloway, J. K. and R. J. Johnson: Some Ob-servations on the Causes and Methods ofRepair of Direct and Recurring InguinalHernias. West. J. of Surg., Obst. & Gynec.,56:473, 1948.

21. Koontz, A. R.: The Use of Tantalum Mesh inInguinal Hernia Repair. Surg., Gynec. &Obst., 92:101, 1951.

22. Idem: Views on the Choice of Operation forInguinal Hernia Repair. Ann. Surg., 143:868,1956.

23. Lotheissen, G.: Zur Radikaloperation derSchenkelhernien. Centrabl. f. Chir., 25:548,1898.

24. Mattson, H.: Use of Rectus Sheath and Supe-rior Pubic Ligament in Direct and RecurrentHernia. Surgery, 19:498, 1946.

25. McVay, C. B. and B. J. Anson: Aponeuroticand Fascial Continuities in the Abdomen,Pelvis and Thigh. Anat. Rec., 76:213, 1940.

26. Idem: Composition of the Rectus Sheath.Anat. Rec., 77:213, 1940.

27. Idem: A Fundamental Error in Current Meth-ods of Inguinal Herniorrhaphy. Surg., Gynec.& Obst., 74:746, 1942.

28. Idem: Inguinal and Femoral Hernioplasty.Surg., Gynec. & Obst., 88:473, 1949.

29. McVay, C. B.: A Fundamental Error in theBassini Operation for Direct Inguinal Hernia.Univ. Hosp. Bull., Ann Arbor, 5:14, 1939.

30. Idem: Inguinal and Femoral Hernioplasty:Anatomic Repair. Arch. Surg., 57:524, 1948.

McVAY AND CHAPP Annals of Surgery510 October 1958

31. Idem: The Pathologic Anatomy of the MoreCommon Hernias and Their Anatomic Re-pair. Springfield, Charles C Thomas, 1954.

32. Idem, Chapter 19: Hernia. Davis-Christopher'sTextbook of Surgery, Sixth Edition. Phil-adelphia, W. B. Saunders Co., 1956.

33. Mueller, C. B. and G. Rader: Inguinal Herniain Children. Arch. Surg., 73:595, 1956.

34. Potts, W. J., W. L. Riker and J. E. Lewis:The Treatment of Inguinal Hernia in Infantsand Children. Ann. Surg., 132:556, 1950.

35. Rice, C. 0. and J. H. Strickler: The Repair ofHernia: With Special Application of thePrinciples Evolved by Bassini, McArthur andMcVay. Surg., Gynec. & Obst., 86:169, 1948.

36. Rienhoff, W. F.: The Use of the Rectus Fasciafor Closure of the Lower or Critical Angle

of the Wound in the Repair of Inguinal Her-nia. Surgery, 8:326, 1940.

37. Russel, R. H.: Inguinal Hernia and OperativeProcedure. Surg., Gynec. & Obst., 41:605,1925.

38. Sanderson, D. and C. 0. Rice: The MoreCommon Methods of Inguinal Hernia Re-pair. A Comparison of the Recurrence Rates.Minn. Med., 31:485, 1948.

39. Tanner, N. A.: "Slide" Operation for Inguinaland Femoral Hernia. Brit. J. Surg., 29:285,1942.

40. Telle, L. D.: Inguinal and Femoral Hernia: AReview of 1,694 Cases. Am. J. Surg., 93:433,1957.

41. Turner, P.: The Radical Cure of Inguinal Her-nia in Children. Proc. Roy. Soc. Med., 5:133, 1912.

DISCUSSION

DR. HENRY HARKINS: Dr. Gilchrist, Membersand Guests: Eighteen years ago this month, I hadthe privilege of hearing a young assistant residenton Dr. Coller's service talk in Detroit on the sub-ject of hernia-not an unnecessary operation eventhen, in 1940. Like St. Paul on the road toDamascus, I saw the light, and have used histechnic ever since. That young assistant residentwas Dr. Chester B. McVay. Dr. McVay deservescredit for having taken his ideas to the laboratory,but even more for not having left them there. Hispractical contributions to the subject of hernia, inmy opinion, rank with the best of our members,past and present-Andrews, Halsted, Koontz, etc.

In brief, my ideas relating to groin hernia arevery similar to those of Dr. McVay. He and I areof the same religion, right or wrong, so to speak.I will comment briefly on only four aspects of histalk:

First, regarding the "missed" femoral hemia, Iwill agree that it is much more common than gen-erally realized. The femoral region should be ex-plored from within through the open indirect sac.

In three successive recurrent femoral hernias, myoperation was the 4th, 7th and 3rd, respectively.There was no evidence the femoral hernias them-selves had ever been touched in the 11 previousoperation for these unfortunate 3 patients. The"missed" femoral hernia syndrome is more com-mon in women, in my experience.

Second, I formerly did not utilize "transitionsutures" as described by Dr. McVay, for the areabetween the internal ring laterally and the Coop-er's ligament sutures medially. Now I do.

Third, we agree with Dr. McVay as to thegreat importance of narrowing the internal ring.

Fourth, we agree as to the need of classifyinghernias into degrees of difficulty, making 4 cate-gories, as shown below.

Only in Grade IV (most direct hernias, femoralhernias, recurrent hernias, large, indirect hernias)do we use the Cooper's ligament repair, in agree-ment with Dr. McVay.

Finally, to indicate one new approach to thesubject, we are trying out the use of the Cheatle-Henry transabdominal preperitoneal approach for

Foutr Grades of Hernia Repair Cheatle-Henry Repair

Fascial NumberInternal Closure, Cooper's Type of Hernia of CasesRing Hessel- Liga-

Sac Tight- bach's ment Indirect inguinal 44Grade Ligation ening Triangle Sutures Direct inguinal 29

Femoral 36I. Infant **-II. Simple * * Sliding 2

III. Interme-diate * * * Total 111 hernias

IV. Radical * * * * (84 patients)