Road culvert flow measurement - Flowmeters | Flow Metering Technology

An Introduction to Wet-Gas Flow Metering

-

Upload

catalin-tutuianu -

Category

Documents

-

view

108 -

download

12

description

Transcript of An Introduction to Wet-Gas Flow Metering

GOOD PRACTICE GUIDE

AN INTRODUCTIONTO WET-GAS FLOW METERING

www.tuvnel.com

Contents

Foreword 2

1. What is a wet gas? 3

1.1 Steam flows 4

1.2 Hydrocarbon flows 4

2 Wet gas flow patterns 5

2.1 Horizontal flow patterns 5

2.2 Vertical flow patterns 6

3 Measuring wet-gas flows 6

3.1 Single phase metering options 7

3.2 Two and three-phase metering options 7

4 Differential pressure meters 7

4.1 Different types of differential pressure meters 8

4.2 Correcting the response of the meter 9

4.3 Commonly used corrections 11

for differential pressure meters

4.4 How to calculate the gas flow rate using 12

a differential pressure meter

4.5 Practical considerations 13

4.5.1 Installations and effects 13

4.5.2 Pressure tappings 14

5 Non-differential pressure flow meters 15

6 Measurement of liquid content 17

6.1 Test separator 17

6.2 Sampling 18

6.3 Tracer method 18

6.4 Microwave technology 18

6.5 Pressure loss ratio method 18

using differential pressure meters

6.6 Advanced signal processing 20

7 Two and three-phase wet-gas meters 20

8 Issues and challenges with wet-gas metering 22

9 Summary 23

10 References 24

Annex 1: Understanding the terminology used in 24

wet-gas flow measurement

Annex 2: Nomenclature and definitions 26

This guide provides an introduction to wet-gas metering which is aimed at people who have little experience in this area. It covers the basic concepts of characterisation and flow regimes before progressing onto the various metering options available to measure the gas and liquid components. This includes single-, two- and three-phase metering, measurement of liquid content, metering challenges and terminology used by industry.

Good Practice Guide

1

Foreword

This good practise guide is aimed at people who are inexperienced in the flow measurement of wet gases but who would

like to advance their knowledge and understanding.

For those not familiar with wet gases it can be rather daunting to first approach the subject because much of the

available literature is normally aimed at people with some experience. Wet-gas flow measurement can be more difficult to

comprehend due to the complexities of a combined flow of a compressible fluid (gas) and a non-compressible fluid (liquid).

This makes the subject slightly more difficult to grasp than the measurement of single phase flows of just liquid or gas.

The guide provides initial direction and help on what you need to consider and where to start when first faced with

the prospect of wet-gas metering. It should enable the reader to be more confident and equipped to understand the

terminology used along with the metering principles that are commonly encountered, before moving on to more advanced

information.

Common examples of wet-gas flows that are metered are in the extraction of natural gas (in the oil and gas industry)

and saturated steam lines - which are commonly encountered in a wide variety of industries. It is important to be able to

measure wet-gas flows to quantify products, reduce costs and optimise the management of systems and resources. An

understanding of wet-gas metering principles can help enable this.

Reading this guide should enable the reader to:

• understandtheterminologyusedinthearea

• understandsomeofthewet-gasmeteringprinciples

• identifywhatmeteringtechnologyisneededfortheirapplication

• makeinformeddecisionsonwet-gasmetering

• dealwithsuppliersofwet-gasmeteringtechnology

Although the document is written for those who have some basic understanding and experience with flow metering, this

is not totally necessary as this document links in with other introductory guides to flow metering to cover the necessary

background.

As this is an introductory guide some of the more complex terminology used in wet-gas flow measurement has not been

fully covered. However, for reference a section has been included at the end of this guide which contains explanations and

definitions of the terminology commonly encountered in this area. The reader should feel more comfortable and equipped

to move on to more in-depth information on wet-gas flows after reading this document, while the reference section

provided will be beneficial to understand more advanced information.

An Introduction to Wet Gas Flow Metering

2

1. What is a wet gas?

This at first may seem a straight forward question but in fact there has been some debate as to its actual definition [1].

In simple terms it can be described as a gas with a small amount of liquid present. In most cases people are mainly

interested in knowing the amount of gas flowing rather than liquid. This depends though on the potential monetary value

represented by the type of liquid present, e.g. gas condensate.

There is no quantitative definition of a wet gas flow that is universally accepted. People have interpreted the definition

ranging from a “humid gas” (i.e. gas saturated with liquid vapour) to multiphase flows with a gas volume fraction (volume

of gas to the total volume of gas+liquid) of 90% or higher.

However, since the gas volume fraction is based on the volumetric flow rates of the liquid and gas phases at actual

conditions, no account has been made of the gas and liquid densities. Liquids are considered as incompressible fluids and

so the density does not tend to change with a change in pressure. Gas on the other hand is a compressible fluid and the

density changes significantly with pressure. If the pressure of a system increases, the gas density increases but the liquid

density will not change. The fluid densities are an important consideration in flow measurement as they relate to the actual

mass quantities of the fluids present.

To account for both the flow rates and densities of the liquid and gas phases it is common practice to define the wetness or

liquid loading of the gas using the Lockhart-Martinelli parameter, referred to as X. This parameter can be calculated from

the mass or volumetric flow rates and the density of the fluids as follows [1]:

Good Practice Guide

3

1. What is a wet gas? cont.

The Lockhart-Martinelli parameter can also be expressed in terms of the gas and liquid densiometric Froude number; this is

a dimensionless number used to express the liquid or gas phase velocity. It is common (and sometimes confusing) to find

different expressions of the Lockhart-Martinelli parameter in different publications. Care should be taken as some older

publications use different definitions for the Lockhart-Martinelli parameter. Reference [1] provides information on the

definitions for wet-gas flow.

The Lockhart-Martinelli parameter is used to define a wet-gas flow with the value of X between zero (i.e. completely dry

gas) and about 0.3. Flows with a Lockhart-Martinelli parameter above 0.3 are usually referred to as multiphase flows.

1.1 Steam flows

Steam, when it is saturated and has water present as a liquid, can be defined as a wet

gas. In this case the gas component is steam and the liquid is very hot water.

Huge amounts of steam are routinely produced by industry in general and it has been

estimated that approximately 50% of the energy consumed by industry is for the

generation of steam. Therefore, the ability to accurately measure the amount of steam

can be extremely important to account for costs. For this reason a comprehensive review

of steam flow metering technology has been conducted separately and is available from

TUV NEL.

1.2 Hydrocarbon flows

Within the oil and gas industry wet-gas flows are commonly encountered, for example, when gas is extracted from

reservoirs where it can contain some liquid, or when extracted dry gas undergoes a change in pressure and temperature,

say across a choke valve, and liquid subsequently condenses out. This is only one example but there are many other

situations where the measurement of wet gas is important.

Within this industry the liquid component can be any combination of water and liquid hydrocarbon. The liquid fraction of

the total hydrocarbon flow is typically a low molecular weight hydrocarbon referred to as the gas condensate.

An Introduction to Wet Gas Flow Metering

2 SI after the French le Systēm International d’Unitės, or the International System. A system based on a particular choice of metric units from which all others can be derived. 4

1.2 Hydrocarbon flows cont.

The hydrocarbon present in the liquid phase depends on the local temperature and pressure conditions. The system

conditions could either change or be such as to enable condensation of liquid from its vapour hydrocarbon form. As

the temperature and/or the pressure changes, then liquid may form from the gas phase. The presence of the liquid can

cause problems and errors in the ability to accurately meter the gas phase flow rate. Changes in the system conditions are

common, for example, when a gas is transported from a reservoir at high temperature and pressure to where it is brought

ashore.

It is common practice to define the amount of water in the liquid phase as a percentage known as the ‘water cut’. This

liquid phase may have a water cut anywhere between 0% and 100%.

2. Gas flow pattern

To accurately meter wet-gas flows, it is advisable to understand how the liquid and gas phases are distributed within a pipe

as this can affect the response of the measuring equipment. For example, the liquid can be flowing along the bottom of

the pipe or be dispersed as droplets in the gas phase. The distribution of the liquid and gas phases within a system are

classified by so-called “flow patterns”; these are illustrated below.

2.1 Horizontal flow patterns

In horizontal pipes several flow patterns are observed:

Stratified flow – here the liquid flows

along the bottom of the pipe and the less

dense gas occupies the upper part of

the pipe.

Stratified-Wavy – this is basically stratified

flow with a wavy gas-liquid interface as

shown below.

Transitional – this is the flow pattern observed when the gas velocity increases and begins to lift liquid from the stratified

layer into the gas stream. This pattern occurs as a transition between the stratified-wavy flow and annular flow pattern,

which is described below.

Annular - the liquid flows as a film on the

pipe walls with the gas flowing inside the

liquid forming a central core. In horizontal

pipes, the effect of gravity will tend to ensure

that more liquid is at the bottom of the pipe

than at the top.

Good Practice Guide

5

2.1 Horizontal flow patterns cont.

Annular-mist – this pattern occurs as the gas velocity increases and picks up some of the liquid into the gas core as

droplets or mist.

2.2 Vertical flow patterns

In vertical pipes the main flow patterns observed are annular flow and

annular-mist flow for wet-gas conditions.

3. Measuring wet-gas flows

Knowing what measurements you want will help dictate the type of

metering technology that is required.

Gas flow rate only?

What measurements are Gas + liquid flow rate?

needed or important? Gas + liquid hydrocarbon + water flow rates?

Single-phase meter

Wet gas metering options Two-phase meter Which one?

Three-phase meter

An Introduction to Wet Gas Flow Metering

Flow direction

}

6

3.1 Single-phase metering options

This option allows for the measurement of the gas flow rate only, but the effect of the liquid on the meter response should

be accounted for. The required uncertainty of measurement can be a significant factor when determining whether or not to

correct for the liquid presence.

It may be that the low liquid content and/or low financial value of the liquid means that only the gas measurement is

important.

Single-phase meters can generally be divided into those using differential pressure techniques and non-differential pressure

techniques.

3.2 Two- and three-phase metering options

Two- and three-phase meters provide information on the gas and total liquid flow rates or the gas, liquid hydrocarbon and

water flow rates. The metering principles of these types of meters are covered in Section 7.

4. Differential pressure (DP) meters

Differential pressure (DP) meters are one of the most commonly used single-phase meter types available for wet-gas flow

measurement. If you are unfamiliar with differential pressure meters then it may be advisable to first read the introductory

guide to differential pressure meters so that you can fully understand their use in single-phase conditions. This guide is

available from TUV NEL.

When a differential pressure flowmeter is used in wet-gas conditions the meter tends to ‘over-read’ the amount of gas

passing through it. This means that the estimated quantity of gas determined by the flow meter is higher than the actual

amount passing through it. Therefore the meter response must be ‘corrected’ to provide the actual gas mass flow rate.

The over-reading is defined as the uncorrected gas mass flow rate measured in wet-gas conditions, divided by the actual

gas mass flow rate that would be obtained if the gas flowed alone in the pipe.

gas mass flowrate measured in wet -gas conditions

gas mass flowrate measured in dry -gas conditionsOver-reading =

When using the equation to calculate the gas mass flow rate the over-reading simplifies down to approximately the root of

the differential pressure measured in wet-gas conditions divided by that measured in dry-gas conditions.

Good Practice Guide

7

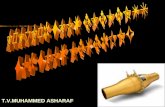

4.1 Different types of differential pressure meters

Meters commonly used are:

• Venturitubes

• V-conesorcone-typemeters

• Orificeplates

Information on using differential pressure meters is available from the introductory guide to differential pressure meters by

TUV NEL.

Venturi tube

V-cone meter

Orificeplatefittedinto pipe

An Introduction to Wet Gas Flow Metering

8

4.1 Different types of differential-pressure meters cont.

The amount of liquid present can have a different effect on the over-reading response of different differential-pressure

meters; for example the over-reading response for a V-cone may be different to that for a Venturi meter with the same

amount of liquid present at identical flow conditions.

4.2 Correcting the response of the meter

The response of each meter must be ‘corrected’ for the presence of the liquid otherwise significant errors in the

measurement of the gas flow rate can occur. For example, errors of up to 60% and more can occur in the gas flow rate

depending on the meter type used, local flow conditions and liquid content. Serious mis-measurement issues can result

from inadequate corrections for the presence of liquids.

The response of differential-pressure meters are usually presented as a graph showing the over-reading as a function of

the liquid content expressed as the Lockhart-Martinelli parameter, X. The graph below shows what the over-reading for

a differential-pressure meter could look like. It can be seen that the meter over-reading increases with increasing liquid

content.

Illustration of the over-reading response for a

differential pressure meter in wet-gas conditions,

the liquid content is expressed by the

Lockhart-Martinelli parameter.

It should be noted that the shape of the response can be non-linear and is generally different for each type of meter.

The over-reading response of a flow meter is dependent on the wet-gas flow conditions and can be affected by the:

• gasvelocity(viathegasdensiometricFroudenumber)

• flowmeterdiameterratioorbetavalue1

• gasdensity

• gas-liquiddensityratio

• liquidphaseproperties(e.g.density,interfacialtensionandviscosity)

Good Practice Guide

1 The diameter ratio (sometimes called beta or beta ratio) is the ratio between the minimum cross section at the restriction, d, and the pipe diameter, D..9

4.2 Correcting the response of the meter cont.

As an example the graph below shows the actual over-reading response for a Venturi tube of beta 0.4. In this example

the over-reading decreases with an increase in the gas pressure from 15 bar gauge up to 60 bar gauge. It is worth

remembering that the gas density is directly related to the pressure, therefore as the pressure increases then the gas density

is also increased.

Venturi meter (β = 0.4) over-reading as a function of the Lockhart-Martinelli parameter (expresses the liquid

fraction) at gas pressures of 15, 30 and 60 barg.

This example illustrates the effect that the flow conditions can have on the response of the meter. For example, if the

response of the meter (i.e. the differential pressure measurement) is not corrected to account for the presence of the liquid

this can cause an error in the gas flow measurement of ~60% at a pressure of 15 bar and Lockhart-Martinelli parameter of

approximately 0.3. This highlights the importance of correcting for the presence of the liquid.

The reader should be aware that the measurements from differential pressure meters can be affected by a number of

parameters such as:

• Geometry

• Gasvelocity

• Flowpattern

• Pressure

• Temperature

• Liquidviscosity(gasviscositynotthatimportant)

• Liquidsurfacetension

An Introduction to Wet Gas Flow Metering

OR vs X (HP)

1

1.1

1.2

1.3

1.4

1.5

1.6

1.7

1.8

0 0.05 0.1 0.15 0.2 0.25 0.3 0.35

Lockhart-Martinelli Parameter (-)

Ven

turi

Mete

r O

ver-

Read

ing

(-)

60 barg

30 barg

15 barg

10

4.3 Commonly used corrections for differential pressure meters

Corrections or correlations that account for the presence of liquid for Venturi tubes and orifice plates are widely available.

The correlations are used to determine the meter over-reading (via knowledge of X) and then determine the actual gas

mass flow rate. The corrections that have been commonly used by industry are:

Murdockequation[2,3] Orificeplates

Chisholm equation [4]

de Leeuw correlation (modified Chisholm correlation) [5] Venturi tubes

Correlations have been published and are available for V-cone meters but as these were proprietary flow meters there has

been less independent research performed and no standards are available as to their use, even in single phase conditions.

In general the over-reading response of V-cones in wet-gas conditions is usually less than that observed for Venturi tubes;

because of this property V-cone meters have proved very popular for wet-gas metering.

Previous research performed on the effect of Venturi tubes and V-cones in wet gas conditions are available from TUV NEL.

A report titled “The evaluation of dry gas meters in wet gas conditions” provides in-depth information on the performance

of these meters.

Care should always be taken when using a correlation. If it is applied outside the range over which it was obtained then

large measurement errors can occur. For example, the de Leeuw correlation was derived from data using a 4-inch Venturi

tube with a beta of 0.4, however it is now known that beta affects the over-reading in wet gas conditions [6]. Errors of up

to 12% in the gas mass flow rate are known to occur if applying this correlation to larger beta ratios [7].

However, even knowing this there may have been no other choice available to industry but to use the available correlations

and increase the uncertainty of the value of the gas mass flow rate. TUV NEL have recently derived a new correlation for

Venturi tubes that takes into account a greater range of parameters than have been available up to now [7].

This new correlation covers the following:

• nominalpipediametersfrom2-inchto10-inch(50mmto250mm)

• beta0.4to0.75

• gasphasesof

o steam

o hydrocarbon

• liquidphasesof

o hydrocarbon

o water

o very hot water, i.e. from steam (different surface tension from cold water – this appears to have an effect

on the meter response)

Wet-gas correlations used to correct the gas flow to account for the error induced by the presence of liquid provide an

uncertainty of approximately ± 2% for the gas flow using orifices plates and approximately ± 3% for the gas flow using a

Venturi tube. A modified Chisholm correlation is available for orifice plates in wet gas flows [8].

Good Practice Guide

}

11

4.4 How to calculate the gas flow rate using a differential pressure meter

Onceyouhaveyourdifferentialpressuremeasurementtakeninwet-gasflowconditionsyouwillthenneedameasurement

of the liquid flow rate. Techniques to measure the liquid flow rate are summarised in Section 6.

First, calculate the Lockhart-Martinelli parameter, this requires information on the:

• gasflowrate(canestimateatfirstfromthewet-gasdifferentialpressuremeasurement)

• liquidflowrate

• liquiddensity

• gasdensity

Then use an appropriate wet-gas correlation to relate the Lockhart-Martinelli parameter to the over-reading in the

differential pressure. The over-reading is used to calculate the mass flow of the gas as if it was dry. An estimated value of

the dry gas flow rate is first used and then an iterative calculation procedure is applied until the ‘estimated’ input value of

the dry gas flow rate (used to calculate the Lockhart-Martinelli parameter) is within an acceptable convergence range with

the output value. Usually the computation method is programmed into a flow computer to automatically calculate the

actual dry-gas flow rate. The liquid flow rate, gas and liquid densities are usually entered into the computer. Gas and liquid

densities can be determined from sampling the flows and subsequent analysis of the fluids.

Iterative procedure to calculate the actual gas flow rate in wet-gas conditions

An Introduction to Wet Gas Flow Metering

12

4.5 Practical considerations to wet-gas metering using differential pressure devices

Venturi tubes are commonly selected instead of orifice plates to meter wet-gas flows as they are considered to be

much more durable, more resistant to erosion and can withstand higher differential pressures without incurring

damage to the device.

Orificeplates,whenusedforwet-gasflowmeasurement,shouldideallybeeasilyaccessibleandcheckedregularly

fordamageorerosionasthisaffectstheaccuracyoftheflowmeasurement.Orificeplatesaremainlyusedfor

topside metering applications.

Upstream face of orifice plate Downstream face of orifice plate

Orificeplatescanbedamagedbyslugsofliquidimpactingontheirsurfaceandbendingtheplate,andthiscan

affect the flow measurement.

It should be noted that the use of thicker orifice plates can withstand higher differential pressures and the impact

forcefromliquidslugs.ThemaximumplatethicknesspermittedbythestandardISO5167-22 is 0.05 times the

pipe diameter, this is a plate thickness of 5 mm for a nominal four-inch pipe. For pipe diameters between 50 mm

and 64 mm a plate thickness of up to 3.2 mm is allowed.

4.5.1 Installation effects

It is recommended to install Venturi tubes and orifice plates in a horizontal position as any liquids which collect in the

impulse lines from Verturi tubes installed in a vertical orientation can affect the flow measurement.

Good Practice Guide

2ISO5167-1to4istheinternationalstandardcoveringthe‘Measurementoffluidflowbymeansofpressuredifferentialdevicesinsertedincircularcross-sectionconduitsrunningfull’.Thisdocumentprovidesinformation on how the flow in full pipes should be measured to ensure measurement consistency across industries. It includes information on orifice plates and Venturi tubes to meter single phase flows of

liquid and gas, such as equations to calculate the flow, tolerance of manufacture of the meter, uncertainty of flow measurement and installation requirement etc.13

4.5.1 Installation effects cont.

The straight pipe length upstream of the meter is recommended to be as long as possible to minimise the flow

measurement uncertainty. For more information on installation effects in single-phase metering please refer to the

introductory guide on installation effects (available from TUV NEL).

The reduced pipe lengths that have been recommended for dry gases are not recommended for wet gas conditions. This is

to ensure the fluids have ‘settled’ into their ‘natural’ flow regime at the meter. Correlations to correct for the meter over-

reading have assumed no flow disturbances upstream of the meter to change the flow regime.

4.5.2 Pressure tappings

The pressure tappings are the holes machined through the pipe wall, flange or meter that allow the pressure to be

measured by a suitable sensor (see the diagram below). The tube connecting the pressure tapping to the pressure sensor is

referred to as the impulse line. A report on impulse lines for differential pressure flowmeters is available from TUV NEL.

Pressure tapping and impulse line connection

to a pressure sensor to measure the pressure

within the pipe

Some general guidance and good practice on how to obtain differential pressure measurements in wet-gas conditions

are summarised below. The quality of your flow measurement is very much dependent on the quality of the differential

pressure measurement.

Natural gas flows

• Thepressuretappingsshouldbeatthetopofthepipetoensurethatliquidstrappedintheimpulselinecandrain

back into the pipe.

• Thetemperatureofthegaswilltendtowardsambientonceitleavesthemainpipe–thedropintemperaturecan

cause condensation of the gas to liquid.

• Theimpulselinesshouldbekeptasshortaspossibletolimittemperaturedrop.

An Introduction to Wet Gas Flow Metering

14

4.5.2 Pressure tappings cont.

Trace heating can be applied to the impulse lines to prevent hydrate formation3 in natural gas pipelines as the drop in

temperature of the gas as it moves away from the main pipe can cause hydrates to form and block the impulse line, thus

providing inaccurate pressure measurements. The heating can also limit the formation of liquid in the impulse line.

Trace heating or insulation can be used around the pipe walls to prevent hydrate formation and reduce or eliminate the

potential condensation of liquids from a reduction in temperature. This may even be sufficient in some cases to eliminate

the need for wet-gas flow measurement entirely if the temperature is maintained such that no condensation occurs and the

fluid is completely in the gas phase.

Pipework upstream of differential pressure meters should be designed such that bends or other installations upstream

of the meter encourage any stratified or flowing liquid to flow at the bottom of the pipe. This is recommended as the

correlations available to correct the meter over-reading were derived from the fluids flowing in a stratified flow regime.

Steam flows

For the metering of steam the pressure tapping should be horizontal and the impulse line should be sloping downwards.

This arrangement is to encourage condensation of the fluid in the impulse line so that the pressure sensor is exposed to

colder water as high temperature steam can damage the pressure sensors. The impulse lines can be filled with water prior

to exposure to line conditions to ensure no damage to the sensors by the steam.

5. Non-differential pressure flow meters

Although differential pressure flow meters are commonly selected for wet-gas measurement there are other metering

options available. In some cases a meter may have been installed to meter dry gas but for various reasons there is some

liquid present within the gas flow. Therefore knowledge of the effect of the liquid presence on the meter is required. A

brief summary of the known effects on other single phase meters exposed to wet-gas conditions is provided below.

Turbine meters should ideally never be used

to meter wet gas as the meter can be damaged

and the meter response is unpredictable.

Good Practice Guide

3 Hydrates are solid crystalline structures which can form in natural gas and water mixtures under certain pressure and temperature combinations. This is covered in Section 8.1.15

5. Non-differential pressure flow meters cont.

Ultrasonic meters will always over-read the gas flow

rate and the presence of the liquid can affect the

proper functioning of the meter by blocking transducers

etc. Have been successful when the presence of liquid

is very low [9].

Sound pulses are passed back and forth between the transducers – one upstream and one downstream. A sound pulse

travelling “against” the flow direction takes longer to travel the intervening distance than a sound pulse travelling in the

direction of flow. The difference in the time taken is proportional to the flow velocity.

Vortex meters will always over-read the gas flow rate

and the liquid present can affect the function of the

meter, depending on the design.

The principle of operation of a vortex meter: as the fluid flows past a block or obstruction in the flow, vortices are

generated at a frequency proportional to the fluid velocity.

Coriolis meters can have an unpredictable behaviour in wet gas conditions but there is current research into their use in

this area [10].

With a Coriolis meter the fluid is directed through a vibrating flow tube, Coriolis forces exerted by the moving fluid cause

the tube to twist. The amplitude of the twist is related directly to the mass flow rate.

More information on the effect of wet-gas conditions on single phase meters can be obtained from the TUV NEL report

“The evaluation of dry gas meters in wet gas conditions”.

An Introduction to Wet Gas Flow Metering

d

16

6. Measurement of the liquid content

Separate liquid measurement is important and necessary for use with single-phase meters to correct for the presence of the

liquid.

There are a number of techniques available for measuring the liquid content, these include:

• Testseparator

• Sampling

• Tracer

• Microwavetechnology(waterspecific)

• Overallpressurelossacrossdifferentialpressuremeters

• Infrared

• Advancedsignalprocessing

In the majority of these methods it is usually assumed that the liquid flow rate is constant between consecutive

measurements, the timing of which can vary by months.

Each method is briefly explained below.

6.1 Test separator

This is the conventional approach to determine the individual phase flow rates and involves the physical separation of the

liquid from the gas, with each phase then metered separately. This method provides flow rate information on all phases

present and can be used to check the performance of a wet-gas flow meter.

Validation of a wet-gas meter using a test separator

The pressure and temperature of the fluids at the test separator may be different to that at the flow meter. If this is true

then the gas and liquid flow rates must be corrected to the conditions at the meter to account for possible phase changes

and/or mass transfer between the liquid and gas phases.

Another issue to consider is that the separation will very likely not be 100% efficient and there may be liquid carry-over

into the gas stream and gas carry-under into the liquid stream(s).

Good Practice Guide

17

6.2 Sampling

Sampling is where a physical wet-gas sample is removed from the pipeline for analysis. There are various commercial wet-

gas sampling systems available.

Challenges with this technique:

• ensuringasampleiscollectedthatisrepresentativeofboththegasandliquidphasefractions

• ensuringnomasstransferoccursbetweentheliquidandgasduringsampling.

Schematic of flow sampling

6.3 Tracer method

This technique involves the injection of tracer dyes into the flow and then a sample is taken at a specified distance

downstream of the injection point to measure the dilution of the tracer(s). The concentration/dilution of the tracer in the

liquid phase is used to calculate the liquid flow rate. Tracers are selective to oil and water phases and the samples do not have

to be representative of the actual volume fractions of the various phases existing in the main pipeline. The technique itself can

be rather cumbersome to perform and it can be difficult to get to the right point to conduct the test, access issues etc.

6.4 Microwave technology

Microwave techniques can be used to detect the overall water fraction (in both the liquid and gas phases). The technique

exploits the much higher permittivity of water than hydrocarbons.

As the technique only detects and measures the water component then the liquid hydrocarbon fraction must be

determined by another method, usually by Pressure-Volume-Temperature (PVT) calculations, which calculate the fraction of

the hydrocarbon present in both the gas and liquid phases.

Several manufacturers of wet-gas meters have incorporated microwave technology into their meters.

6.5 Pressure-loss ratio method using differential pressure meters

The pressure drop across the primary measurement section of a Venturi tube is partly recovered downstream of the meter.

In dry gas conditions the recovery is around 80% to 95%, however in wet gas conditions the liquid presence produces a

smaller pressure recovery and this difference can be exploited to provide a measure of the liquid fraction.

The method involves using an additional pressure tapping downstream of the Venturi tube to provide a measure of the

overall pressure loss, Δp2, as shown in the schematic below.

An Introduction to Wet Gas Flow Metering

18

6.5 Pressure-loss ratio method using differential pressure meters cont.

Venturi tube illustrating overall pressure loss (Δp2) and the differential pressure (Δp1) used to calculate the

pressure loss ratio (Δp2/Δp1)

The pressure loss ratio (Δp2/Δp1) correlates with the liquid content and is most sensitive at low liquid loading (i.e. low

values of Lockhart-Martinelli parameter)

At low liquid loading the pressure loss ratio method can be used with orifice plates and Venturi tubes to calculate the

Lockhart-Martinelli parameter. Its use is limited to calculating values of the Lockhart-Martinelli parameter up to maximum

values of approximately 0.05. It should be noted that the method is known to be affected by the system pressure (gas-

liquid density ratio), gas velocity and beta value.

The graph below illustrates the relationship between the pressure loss ratio and the Lockhart-Martinelli parameter.

TUV NEL has derived equations to use the pressure loss ratio with Venturi tubes to calculate the Lockhart-Martinelli

parameter [7].

Good Practice Guide

PLR vs X (LP)

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0 0.05 0.1 0.15 0.2 0.25 0.3 0.35

Lockhart-Martinelli Parameter (-)

Pre

ssu

re L

oss R

ati

o (

-)

gas pressure 15 barg

gas pressure 50 barg

19

6.5 Pressure-loss ratio method using differential pressure meters cont.

The pressure loss ratio is used within some commercial wet-gas meters to calculate the liquid content at low liquid loading.

The method is particularly useful to monitor changes in the liquid fraction when using a flow meter and can be used to

detect if liquid is present within a gas stream.

6.6 Advanced signal processing

This is basically where the liquid has an effect on the measured variables, for example, pressure fluctuations in the

differential pressure measurement of DP meters, or the shift in the speed-of-sound in ultrasonic meters. Complex analysis

and recognition of patterns has been used in various wet-gas flow meters to provide extra information and to help in

determining the liquid and gas flow rates.

7. Two and three-phase commercial wet-gas meters

There are various meters marketed specifically for wet-gas flow measurement to meter both the liquid and the gas flow

rates directly. Most of the available meters use some sort of differential pressure device and may incorporate additional

metering techniques and other technologies to determine the water and liquid hydrocarbon fractions. Some of the

operating principles of wet-gas meters are summarised here to provide a basic understanding of how they determine the

gas and liquid flow rates.

Oneoftheprinciplesusedtomeasureboththeliquidandgasflowsistousetwodifferentialpressuredevicesinseries,

which provide the same flow rate for dry gas but each device has a different over-reading response when liquid is present.

The difference in over-reading response is exploited and correlations are then applied to the data to determine both the gas

and liquid flow rates.

An Introduction to Wet Gas Flow Metering

20

7. Two and three-phase commercial wet-gas meters cont.

Some wet-gas meters use one differential pressure device in series with another non-differential pressure meter (e.g.

a clamp-on sonar-based meter) and use the difference in the meter responses to the local wet-gas flow conditions to

estimate the individual phase flow rates.

Othermetersusepartialseparationsystemstometertheseparatestreamsofliquidandgas.Thesetypesofmeterare

generally based around existing multiphase meter designs and are larger, more expensive and more complex systems.

Pressure loss measurements are used in some of the meters to determine the liquid content at low liquid loadings.

Oncetheliquidandgasfractionshavebeendeterminedviathevariousmeteringtechnologies,manywet-gasmetersthen

use Pressure-Volume-Temperature (PVT) models to calculate the total fraction of hydrocarbons present in both the gas and

liquid phases. Using the above the water-liquid ratio of the liquid phase can then be determined.

It should be noted that while many of the single-phase meters used for measuring wet-gas flows are recommended to be

installed in a horizontal position, the majority of the two and three-phase wet gas flow meters are recommended to be

installed in a vertical position. This is to force the multiphase flow into a more symmetrical flow pattern type such that the

ability of the particular metering technology in use is enhanced. Horizontal installation is recommended for differential

pressure meters to ensure the impulse lines do not fill with liquids.

Othertechniquesincorporatedintocommercialwet-gasflowmetersusedtocalculatethewaterfractionare:

• Microwavetechnology

• Gammaray

• Infraredtechnology

Otherwetgasmeteringprinciplesusedinclude:

• advancedsignalprocessing

• neutralnetworkinterpretation-meter“trained”topredictindividualphaseflowrates

• 3Dbroadbandradiofrequencysystemstoimagetheflow

• sonarsensorstomeasurethespeedofturbulent“eddies”generatedinthewet-gasflow

• vortexmeterincombinationwithadifferentialpressuredevice

Good Practice Guide

21

8. Issues and challenges with wet-gas metering

A useful paper which covers the real world practicalities of wet-gas metering was provided by Stobie [9] at a previous TUV

NEL Wet Gas Flow Measurement Seminar. This included information on different commercial meters available as well as

useful advice on the issues likely to be encountered.

8.1 Hydrates

Hydrates are solid crystalline structures which can form in natural gas and water mixtures under certain pressure and

temperature combinations. The formation and build-up of hydrates within pipes can cause measurement errors, damage

equipmentorevenblockanentirepipeline(seeimagebelow).Operatorsofnaturalgassystemsareverykeentodetectif

water is present so that they can prevent the formation of hydrates before any problems can occur. Hydrate inhibitors such

as methanol can be added to prevent their formation.

Hydrate blockage in

a section of pipe [11]

8.2 Flow conditioners

Flow conditioners are commonly used upstream of gas and liquid flow meters to correct

asymmetrical flow profiles, reduce swirl and to reduce the recommended upstream pipe

length before a flow meter while maintaining flow measurement accuracy. However,

the use of flow conditioners is not recommended for wet-gas conditions. Hydrates can

form in these flow conditions and block them. Also liquids can build up in front of flow

conditioners and result in a skewed flow profile, which can affect the flow measurement.

Zanker flow conditioner plate

An Introduction to Wet Gas Flow Metering

21 22

9. Summary

• Wet-gasflowmeasurementissignificantlymorecomplicatedthanmeasuringthesinglephaseflowofdrygas.

• Thepresenceoftheliquidchangestheresponseofdry-gasflowmeters.

Therefore the meter response must be corrected to provide the actual dry-gas flow rate.

Separate measurement of the liquid flow rate is necessary to calculate the actual dry-gas flow rate.

• Differentialpressuremetersarethemostcommonlyusedsingle-phasemetertypetomeasurewetgasflow.

The DP meter will over-read in wet gas conditions.

Use a wet-gas correlation to correct the meter response and obtain

the actual dry-gas flow rate. Knowledge of the liquid flow rate is

required for the correlation.

• Specificcommercialwet-gasflowmetersareavailableto.

Simultaneously measure both the gas and liquid flow rates

or

Measure the gas flow rate, water flow rate and hydrocarbon liquid flow rate in the stream.

You may find the list of definitions at the end of this document particularly helpful in understanding the terminology commonly used in wet-gas flow measurement

Good Practice Guide

G a s

L iq u id

L iq u id

h y d r oc a r b on

W a te r

Over-read

ingrespon

se

(no

units

)

23

Over-reading

10. References

[1] Hall, A.,Griffin, D., Steven, R. “A discussion on wet gas flow parameter definitions”, In Proc. of 25th North Sea

FlowMeasurementWorkshop,October2007.

[2] Murdock,J.W.“Two-PhaseFlowMeasurementswithOrifices”,JournalofBasicEngineering,Vol84,

pp 419-433, 1962.

[3] Chisholm,D.“FlowofIncompressibleTwo-PhaseMixturesthroughSharp-EdgedOrifices”,JournalofMechanical

Engineering Science, Vol 9, No. 1, 1967.

[4] Chisholm,D.“ResearchNote:Two-PhaseFlowthroughSharp-EdgedOrifices”,JournalofMechanicalEngineering

Science, Vol 19, No. 3, 1977.

[5] De Leeuw, R. “Liquid Correction of Venturi Meter Readings in Wet-Gas Flow”, in Proc. of 15th North Sea Flow

MeasurementWorkshop,Norway,paper21,October1997.

[6] Stewart, D. G. “Application of Differential Pressure Meters to Wet Gas Flow”, in Proc. of 2nd South East Asia

Hydrocarbon Flow Measurement Workshop, March 2003.

[7] Reader-Harris, M. J., Graham, E. M. “An improved model for Venturi-tube over-reading in wet gas”, in Proc. of

27thNorthSeaFlowMeasurementWorkshop,October2009.

[8] Steven, R., Stobie, G., Hall, A. “Further evaluation of the performance of horizontally installed orifice plate and

cone differential pressure meters with wet gas flows” in Proc. of 7th South East Asia Hydrocarbon Flow

Measurement Workshop, March 2008.

[9] Stobie, G. J. “The Conocophillips perspective on wet gas metering”, In Proc. of NEL Wet Gas Flow Measurement

Seminar, September 2004.

[10] Lansangan, R., Skinner, J., Reese, M., Toro, A. D., Tombs, M., Duta, M., Zhou, F., Henry, M. “Coriolis mass flow

metering for wet gas”, Measurement and Control, Vol 41/7, September 2008

[11] ASME MFC-19G-2008 Technical Report, “Wet gas flowmetering guidelines”

Annex 1: Understanding the terminology used in wet-gas flow measurement

Basic Definitions

Fluid - A substance readily assuming the shape of the container in which it is placed.

Gas - Hydrocarbons in the gaseous state at ambient temperature and pressure.

Oil - Hydrocarbons in the liquid state at ambient temperature and pressure.

Phase - Within the bounds of wet gas or multiphase flow, the term refers to either oil, gas or water flows in a mixture of

any number of the three.

Multiphase flow - Two or more phases flowing simultaneously in a conduit.

Emulsion - Colloidal mixture of two immiscible flows; one fluid dispersed in the form of droplets (dispersed phase) within

the other (continuous) phase.

Good Practice Guide

24

Annex 1: Understanding the terminology used in wet-gas flow measurement cont.

Classifications for Wet Gas Flow

Flow regime - The physical geometry exhibited by a wet gas or multiphase flow in a conduit, for example, stratified water/

gas flow – liquid flowing at the bottom of the conduit with the gas flowing above it (not usually at the same actual

velocity).

Homogeneous flow - A wet gas or multiphase flow in which all the phases are evenly distributed over the cross-section of a

closed conduit. Note: the composition is the same at all points.

Measurable Quantities

Mass flow rate - The mass of fluid flowing through a cross-section of a conduit per unit time.

Volume flow rate - The volume of fluid flowing through a cross-section of a conduit per unit time.

Phase flow rate - The amount of one phase of a multiphase flow flowing through a cross-section of a conduit per unit time.

Note the phase flow rate may be specified as being either ‘mass’ or ‘volume’ flow rate.

Multiphase flow rate - The total amount of the two or three phases of a multiphase flow flowing through a cross-section of

a conduit per unit time. Note: this may be specified as being either ‘mass’ or ‘volume’ flow rate.

Phase velocity - The velocity of one phase of a multiphase flow at a cross-section of a conduit.

Multiphase velocity - The flow velocity of a multiphase flow at a cross-section of a conduit.

Superficial phase velocity - The flow velocity a single phase of a multiphase flow would have, assuming that it occupies the

whole conduit itself.

Slip - Term used to describe the flow conditions that exist when the phases have different velocities at a cross-section of a

conduit.

Slip ratio - The ratio between two phase velocities.

Slip velocity - The phase velocity difference between two phases.

Velocity profile - The mean velocity distribution of a fluid at a cross-section of a conduit.

Phase area fraction - The cross-sectional area locally occupied by one of the phases of a multiphase flow, relative to the

cross-sectional area of the conduit at the same local position. Note: this may be also referred to as hold-up. (hold-up

generally applies to liquid area fraction only)

Phase mass fraction - The mass flow rate of one of the phases of a multiphase flow, relative to the total multiphase mass

flow rate.

Phase volume fraction - The volume flow rate of one of the phases of a multiphase flow, relative to the total multiphase

volume flow rate.

Void fraction - The cross-sectional area locally occupied by the gaseous phase of a multiphase flow, relative to the cross-

sectional area of the conduit at the same local position.

Gas-liquid ratio (GLR) - The gas volume flow rate, relative to the total liquid volume flow rate at standard temperature and

pressure (s.t.p).

Gas-oilratio(GOR) - The gas volume flow rate, relative to the oil volume flow rate at s.t.p.

Gas volume fraction (GVF) - The gas volume flow rate, relative to the total multiphase volume flow rate, at the local

temperature and pressure. Note: this is normally expressed as a percentage.

Water cut (WC) - The water volume flow rate, relative to the total liquid volume flow rate at s.t.p. Note: this is normally

expressed as a percentage.

Water-in-liquid ratio (WLR) - The water volume flow rate, relative to the total liquid volume flow rate at local temperature

and pressure. . Note: this is normally expressed as a percentage.

An Introduction to Wet Gas Flow Metering

25

Annex 2: Nomenclature and definitions

Gas Mass Flow rate [kg/s]

Liquid Mass Flow rate [kg/s]

Gas Density [kg/m3]

Liquid Density [kg/m3]

Superficial Gas Velocity [m/s]

The velocity that the gas phase from a two phase flow would have if it travelled alone

and completely fill the pipe.

Superficial Liquid Velocity [m/s]

The velocity that the liquid phase from a two phase flow would have if it travelled alone

and completely fill the pipe.

GVF Gas Volume Fraction [-]

The ratio of gas volumetric flow rate to total volumetric flow rate.

Void Fraction [-]

The fraction of the pipe area at a given cross-section that is occupied by the gas phase.

Note: this can differ significantly from the GVF if the gas and liquid velocities are different (slip flow).

Gravitational Acceleration [m/s2]

Upstream Pipe Diameter [m]

Discharge Coefficient (Venturi or other DP meter)

Dry Gas Flow Coefficient (Venturi or other DP meter)

Modified Lockhart-Martinelli parameter [-]

A dimensionless number used to express liquid fraction.

Gas Densiometric Froude Number [-]

A dimensionless number used to express gas velocity.

Mass fraction of liquid in gas [-]

Good Practice Guide

gm

lm

gρ

lρ

gv

lv

α

g

D

dC

εECK dg =

l

g

g

l

mm

Xρ

ρ=

gl

ggg Dg

vFr

ρρ

ρ

−=

lg

ll mm

mx+

=

gm

lm

gρ

lρ

gv

lv

α

g

D

dC

εECK dg =

l

g

g

l

mm

Xρ

ρ=

gl

ggg Dg

vFr

ρρ

ρ

−=

lg

ll mm

mx+

=

gm

lm

gρ

lρ

gv

lv

α

g

D

dC

εECK dg =

l

g

g

l

mm

Xρ

ρ=

gl

ggg Dg

vFr

ρρ

ρ

−=

lg

ll mm

mx+

=

gm

lm

gρ

lρ

gv

lv

α

g

D

dC

εECK dg =

l

g

g

l

mm

Xρ

ρ=

gl

ggg Dg

vFr

ρρ

ρ

−=

lg

ll mm

mx+

=

gm

lm

gρ

lρ

gv

lv

α

g

D

dC

εECK dg =

l

g

g

l

mm

Xρ

ρ=

gl

ggg Dg

vFr

ρρ

ρ

−=

lg

ll mm

mx+

=

gm

lm

gρ

lρ

gv

lv

α

g

D

dC

εECK dg =

l

g

g

l

mm

Xρ

ρ=

gl

ggg Dg

vFr

ρρ

ρ

−=

lg

ll mm

mx+

=

gm

lm

gρ

lρ

gv

lv

α

g

D

dC

εECK dg =

l

g

g

l

mm

Xρ

ρ=

gl

ggg Dg

vFr

ρρ

ρ

−=

lg

ll mm

mx+

=

gm

lm

gρ

lρ

gv

lv

α

g

D

dC

εECK dg =

l

g

g

l

mm

Xρ

ρ=

gl

ggg Dg

vFr

ρρ

ρ

−=

lg

ll mm

mx+

=

gm

lm

gρ

lρ

gv

lv

α

g

D

dC

εECK dg =

l

g

g

l

mm

Xρ

ρ=

gl

ggg Dg

vFr

ρρ

ρ

−=

lg

ll mm

mx+

=

gm

lm

gρ

lρ

gv

lv

α

g

D

dC

εECK dg =

l

g

g

l

mm

Xρ

ρ=

gl

ggg Dg

vFr

ρρ

ρ

−=

lg

ll mm

mx+

=

gm

lm

gρ

lρ

gv

lv

α

g

D

dC

εECK dg =

l

g

g

l

mm

Xρ

ρ=

gl

ggg Dg

vFr

ρρ

ρ

−=

lg

ll mm

mx+

=

gm

lm

gρ

lρ

gv

lv

α

g

D

dC

εECK dg =

l

g

g

l

mm

Xρ

ρ=

gl

ggg Dg

vFr

ρρ

ρ

−=

lg

ll mm

mx+

=

gm

lm

gρ

lρ

gv

lv

α

g

D

dC

εECK dg =

l

g

g

l

mm

Xρ

ρ=

gl

ggg Dg

vFr

ρρ

ρ

−=

lg

ll mm

mx+

=

gm

lm

gρ

lρ

gv

lv

α

g

D

dC

εECK dg =

l

g

g

l

mm

Xρ

ρ=

gl

ggg Dg

vFr

ρρ

ρ

−=

lg

ll mm

mx+

=

=+

=

=

=

26