An Eclectic Methodological Analysis: Music from Once Upon ... · PDF fileMusic from Once Upon...

-

Upload

truongthuy -

Category

Documents

-

view

223 -

download

0

Transcript of An Eclectic Methodological Analysis: Music from Once Upon ... · PDF fileMusic from Once Upon...

Matthew Steckler Film Music: Historical & Aesthetic Perspectives

Professor Sadoff November 6, 2008

An Eclectic Methodological Analysis:

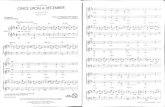

Music from Once Upon a Time in The West By 1969, the year Once Upon a Time in the West was released, the world had its fill of Westerns, both American-made and those of the spaghetti-Western variety as envisioned by Sergio Leone of Italy. While there have been some attempts at Westerns since (most commendably, Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven), it is agreed that Once Upon a Time… to some degree represents a closing chapter for this film genre. The reason is that – on one level - it is a homage to the Western, collaging references to plot, visual cues and witty one-liners from a wide array of previous films, while on yet another level, it seeks to present these references in new ways. Says Christopher Frayling, Leone’s biographer, “there was the mix of recognition and surprise, visual clichés and trompe l’oeil, which Leone reckoned was the key to keeping ahead of his audience” (Frayling 257). In the matter of music, Leone and composer Ennio Morricone, having already completed a cycle of collaboration preceded by a trilogy of Westerns, were now searching for ways to make the music play an even more serious role in the narrative. Leone and Morricone both agreed that having more than two things happening simultaneously only took away from the experience, therefore sound – uncharacteristic of the Hollywood tradition – is given its own spot in time. There is no music in the film’s first twenty minutes, the slow pace of Frank’s men waiting for the train allows for focus on the passing of time, visually and aurally. It is one of the landmark openings in film history, but is beyond the scope of this analysis. Yet the payoff for the score with such an approach is huge, for the music in turn gets its opportunity to shine alone. It is duly noted that Morricone wrote his expansive themes in advance of shooting, and that Leone played the recordings on the set for the actors in order to pace the shoot – this is almost never to be found as a process in film history to date. Syntax Fig. 1 – McBain Massacre The scene where Brett McBain’s family is massacred by Frank Churchill and his men begins the music portion of the film, but not before much time is devoted to exposing the complexity of sound effect (the sound of crickets and the eeriness of them going silent, Maureen McBain singing “Danny Boy”, the scare of birds flocking upward into the sky, the explosive, hyper-real gunshots that slay the family, and the sound of the youngest boy’s feet scrambling outside the house to see what happened). The entire cue that introduces Frank and Harmonica’s themes is devoted to the boy’s demise. Each music cue of Morricone’s is expansive and developmental, the characters react to the music both in pacing and psychology, so there is never a sense of rush to conclude the passage. Frank’s theme, an electric steel guitar melody, plays boldly over a descending bass line in A minor, whose harmonic rhythm is every two bars. Violas play in marcato an eighth note accompaniment based on a 3-note cell, thereby moving in hemiola to 4/4 time and altering one of

Matthew Steckler Film Music: Historical & Aesthetic Perspectives

Professor Sadoff November 6, 2008

its tones with each passing chord (cell 1). Harmonica’s theme enters in response to Frank’s theme at the end of bar 2, and is comprised of the same three tones that begin the viola accompaniment. The entire first section is an even 16 bars, the second half of which begins on

21:29 21:35 21:56 22:20 Boy stops/Cue begins Corpse gaze/Harmonica Men appear/C Maj. Men advance/Rhythm starts

22:33 22:47 23:17 23:40 Men approach/C Maj. Pan to Frank/High note Close-up/Dialogue/Bkgd Gun cocked/Drum cue

Fig. 1 - McBain 24:00 24:30 24:55 Massacre Gun shot/Train dissolve Saloon music/Train stops Jill appears/More music

Matthew Steckler Film Music: Historical & Aesthetic Perspectives

Professor Sadoff November 6, 2008

the relative C major chord and descends in the bass again before an F pivot chord anticipates a V/i return to A minor (cell 2). Violins ascend into octave unison to commence the second section, playing the first four bars as a harmonic rhythmic doubling of the first eight bars in the first section (cell 3). A Mexican deguello-style march rhythm in the snare and lower strings propels this motion forward. The section changes its orchestration, assigning horns to the viola accompaniment, and filling out the harmony with wordless soprano vocals. The fifth bar turns to C major as in the previous section (cell 4), but expands coda-style, both melodically and harmonically. An ascending counter-melody in the horns further heightens the C major moment, and the violin melody responds to it with its own double-ascension, first in triplet, then again more gradually before leaping to a high-F over a pre-cadential D-minor chord as the climax of the entire passage (cell 5). The final section returns to the accompaniment material and the wailing harmonica, underneath dialogue (cell 6). Fig. 2 – Jill’s Theme Cells 9-11 illustrate the transition into Jill’s first scene, marked by train sounds and diegetic saloon music that marks our first sight of her. It is only in her upset at not being met at the station that non-diegetic music ensues. Jill’s theme is the most developed of any of the movie characters, actually comprised of two main sub-themes plus transitional material. A toy piano plays twice through a simple melody voiced in thirds over an equally simple I-IV-V-I progression in 3/4 time (cells 1-2). In its reiteration it is joined by an alto flute (cell 3). The second sub-theme features Edda Dell’Orso again on wordless soprano vocals, as a soloist (cells 4-5). Its beauty is as sophisticated as the first sub-theme’s is simple, reveling in ascending and descending sixths intermittently with step-wise motion, and spanning nearly two octaves in slow 4/4 time. As with Frank’s theme, a descending bass line begins the melody, and the remainder of the progression is identifiably I-IV-I-vi-iii-IV-I. Avoidance of the V here is significant, as it will represent the climax of the sequence 2 bars into the transitional material (cells 6-7). The transition is a majestic horn statement over the relative B minor for 2 bars, and a continuation of that statement with the violins over pre-cadential iv and bII/V chords, swelling into the climactic cadential D 6/4 chord, where violins and soprano both hit their highest points in the range. Instead of resolving to D at the end of this phrase, however, it cadences deceptively to E minor/A, thereby defining those 7 bars as a transition and connecting us back to the second sub-theme, restated (cells 8-10). In the return to this sub-theme, violins play the melody and the harmony is filled by background voices, an occasional seventh chord coloring the progression. The sequence concludes with a double IV-V-I cadence (cell 10). Morricone overall is using traditional Western tonal material, but constantly “coloring” the music with devices reminiscent of the old-West, American variety radio programs, and Italian folk influences.

Matthew Steckler Film Music: Historical & Aesthetic Perspectives

Professor Sadoff November 6, 2008

26:38 26:54 27:07 27:23 Worried/Theme 1 Time confirmed/Cadence All alone/Repeat theme Searching/Soprano vocal

27:57 28:03 28:13 28:27 Station help/End theme 2 Crane to roof/horn transition Town view/D 6/4 chord Town life/Theme 2 repeat

Fig. 2 – Jill’s Theme 28:43 29:12 Introspection/Theme 2 To Sweetwater/Theme ends

Matthew Steckler Film Music: Historical & Aesthetic Perspectives

Professor Sadoff November 6, 2008

Sound-in-Filmic Time Morricone’s passages adhere to classic forms in the Western concert tradition, but not to the detriment of the visual narrative, particularly in Once Upon a Time in the West because of its unusual process of shooting to the music. He avoids Hollywood conventions such as mickey-mousing for the most part, concerned more with depicting an overall mood for each scene, and doesn’t necessarily begin his cues at points in the action where other composers might. Furthermore, the separation of sound effects and dialogue from musical events in the picture allows the music a sense of purpose in its more traditional unfolding, so it can be free to tell its own side of the story. This is the perfect complement to Leone’s psycho-magical shooting style, in which he liberally alternates pensive deep focus close-up shots with panoramic ones. For the McBain Massacre, it is in irony that the music begins just as the boy’s running grinds to a halt (21:29). A more conventional approach might have cued music at the first gunshot, but here we are introduced to it after nearly everyone has already been killed. Another irony implicit is the placement of tonalities with respect to image. The boy’s face is shown in close-up to against a minor tonality, but the first sight of any “bad guys” occurs as the passage turns to a relative major key (21:56). Furthermore, these men are content to take their time doing their dirty work, advancing toward the boy far more deliberately than the rhythmic upsurge in the music might literally suggest (22:20). There is a majesty stated in the music as their advance approaches a climax (22:33), they are still faceless villains and the cut to a rear camera view prolongs their dissemblance. The entire point of the climax is not action per se, but to illustrate musically the slow camera approach from the back of Frank’s head to the front where his identity is first revealed (22:47). By the time anything “happens”, it is dialogue over a reiteration of the accompaniment part (23:17), which we as viewers already have lodged in our memories. Two simple lines: “What are we going to do with this one, Frank?”, and the very drawn-out reply “Now that you’ve called me by name…”, confirm the audience’s belief that these are truly bad men and the perpetrators of the crime, when the music prior may to some have suggested an ambiguity to their nature. The cocking of Frank’s gun is very subtly mickey-moused with a tom-tom figure (23:40), to be used later in the film to signal Frank and Harmonica’s final duel. The music cadences and is punctuated by the same bell tone with which it began, all prior to the actual gunshot, which gets its own spot, transmogrifying sonically into the whistle of a train in the next scene, just as the image dissolves into a close-up of the smoke from that train (24:00). With Jill’s scene Morricone music continues to defy Hollywood expectations. Thanks to the diegetic saloon music (24:30), the actual score isn’t needed to mark our first sighting of Jill McBain. It is only at the first close-up of her as someone distraught - having noticed the station clock (26:38) - that the music cue begins. That we identify it as a child-like melody on a toy piano poses a further irony against her reaction, though we know not at this point its significance (later she discovers a toy town that provides evidence that her dead husband had planned to build a train station at Sweetwater). That said, it is not an altogether happy melody, and in its second iteration (27:07) we come to identify it with her being left alone at the station, much as the theme plays “alone” – or with sparse supporting instrumentation. The start of the second sub-theme marks Jill’s approach to the station to find out how to get home (27:23), the lone soprano voice

Matthew Steckler Film Music: Historical & Aesthetic Perspectives

Professor Sadoff November 6, 2008

also an indicator of the aloneness we see on screen (by then the camera has since revealed all the other train passengers have departed). A mini-opera is made of this theme as it concludes with the stationmaster providing Jill with the help she seeks (27:57). He opens the door to the town, but the audience is introduced to the town not from her vantage point, but from the famous upward crane shot that brings us from behind to the station roof overlooking the town, to the sound of the “heroic” transitional material (28:03). This is – according to sources – the most salient example of Leone wishing to shoot his scenes to a soundtrack, and the shot culminates in the ever-dramatic D 6/4 chord as we gaze with a bird’s eye view down at the town (28:13). A further reveal brings us into closer contact with that town, the horse-drawn carriages, the hustle-bustle of everyday life, and this is narrated by a return to the second sub-theme (28:27). The cue concludes with a camera focus on Jill riding in her own coach (28:43) seemingly thinking about the past (where she came from) and the future (where she is headed), the double cadence in the music appearing wistful, unready to let go. Musical & Filmic Representation Much foresight goes into the choice of musical materials and their evolution in both scenes, and subsequent development throughout the rest of the 165 minute film. A movie rife with symbolism, Once Upon a Time in the West constantly suggests death on the minds of its characters (“something about death”) with the use of sound and image. The McBains are introduced as characters never to be seen again once killed off - but the soundtrack to their massacre is about the two main characters, combining the theme of their killer (Frank) with that of Frank’s adversary (Harmonica), who was introduced in the previous otherwise music-less scene playing his own harmonica. Their themes are played in call-and-response in the same passage just as their destinies are intertwined. Much has been said of the “operatic quality” of this death scene, “enacted with greater ceremony”, Frank and his men emerging from the sagebrush “with the stately leisure of gods” (Fawell: 172, 182). A third player in the scene, the camerawork uses clever pans, tracking shots and close-ups to enliven the slow discourse with music and choreography. Through doing so, at the expense of dialogue or other sound, “Leone made it his task to accentuate the excruciating musical pleasure in film” (Fawell 182). Frank and Harmonica’s final duel plays out with nearly entirely the same musical material, whose purpose this time is to trigger a memory. This lone memory – that of Harmonica as a boy with his brother standing on his shoulders, a noose around his brother’s neck, and Frank sticking a harmonica into his mouth, telling him to play so he could stay standing and keep his brother alive (but he falls and his brother dies) – manifests as the reason Harmonica has sought out Frank the whole time. Frank’s own memory of the event isn’t triggered until Harmonica shoves a harmonica into his mouth, once he has shot Frank. Just prior to this duel, Frank rides up to Harmonica once he has lost everything else – money, land, a woman – and the triumphant trumpet iteration of his theme suggests he will make one final stand for honor between two cowboys of the old breed. Harmonica tells Frank that “only at the point of dying” will he learn who Harmonica is, but the statement the music and dialogue are making is that both characters are not long for a world in which industrialization is rapidly expanding.

Matthew Steckler Film Music: Historical & Aesthetic Perspectives

Professor Sadoff November 6, 2008

Other textual readings of the material beg notice. The use of the “rock” instrument electric guitar for Frank is further – yet sinister - proof of the irony that he is a dying breed in a modernizing world. The tritone that comprises the accompaniment underscores Frank’s ruthless, diabolical nature. The reference to ironies in the use of major and minor tonality as mentioned previously is complemented by Henry Fonda’s own blue eyes and reputation as a “good-guy” actor, yet the music in tandem with his close-ups reveals a deeper psycho-analysis of his complex nature (much of the action in the film in general resides on this psycho-analytical level). Harmonica, though his scenes are not analyzed here, is a mysterious, ubiquitous character. Knowing in hindsight his raison d’etre in the story, it makes sense that his theme alone could cross over from his deeper thoughts into the diegetic realm of making his presence known to others. For Jill’s scene, the weight of the music suggests that she represents a major player in Leone’s greater conception of the West. In the famous crane shot, Fordian in influence, "the camera is timed to arrive at its expansive view of the town just as Jill's theme reaches its expansive section... that Leone and Morricone time to Leone's larger vision of the West under construction" (Fawell, 184). The theme of building a new life figures not only into Jill’s character, but also around the character of Morton the businessman, who aspires to build a railroad through the West to the Pacific. Both characters represent progress, the three cowboys Harmonica, Frank and Cheyenne the counter to that progress. Jill does not yet realize her station in life, instead a disembodied soprano voice illustrates her reflection on the past as she rides through town. The pans and tracking shots run in a motion contrary to the motion of the carriages, and she feels displaced in a bustling town that carries on without her, but the ultimate settling on her face as she thinks and music plays reinforces the idea that her role in others’ lives will figure prominently. Even without knowing her family is dead, she is disappointed in the West, yet somehow “she was meant to get off here” (Fawell 186). Like with Harmonica and Frank, memory becomes an important device in Jill’s world. The life she has left behind as a prostitute in New Orleans is triggered in memory whenever she encounters a difficult path ahead, the toy piano gently narrating this memory. Further in the film Jill remembers a toy sign reading “Station” in the McBain house, the same shape as an unpainted sign among Brett McBain’s unfinished construction projects – this memory triggers the realization Brett intended to build a train station over the only source of steam water within 50 miles: his Sweetwater estate (a power struggle for the estate thereby ensues). Her theme is what plays as she rummages through the house to discover Brett’s belongings in the first place, therefore Jill’s tendency to wander in thought becomes crucial to the plot. By the end of the film, all other threats to the estate thwarted, Jill is left alone without a prospect for love (her two prospects Harmonica and Cheyenne will soon be gone), but Cheyenne suggests she look after the many men out there who continue to realize Brett’s dream of building Sweetwater. In the most poignant iteration of her theme, Jill brings the men water, while they are fascinated with the sight of her, and implicitly her “woman’s touch” will assure progress of being achieved.

Matthew Steckler Film Music: Historical & Aesthetic Perspectives

Professor Sadoff November 6, 2008

The Filmic World Sergio Leone and Ennio Morricone decided to make one final homage to the Western genre with Once Upon a Time in The West. The film should be seen as sort of meta-Western, a movie replete with references to great moments in seminal works such as Stagecoach and High Noon – for example, the pointing to noon on the town clock above, to the tune of battle drums, that signals Harmonica and Frank’s duel ahead. Leone was in love with the Western, but his left-leaning political beliefs and critical eye toward American film’s self-congratulatory, manifest destiny aesthetic predilections meant he had to throw in a few statements to perfect the genre as he saw it. The swirling, bombastic, fanfare-laden scores of American Westerns were one example of how not to do Westerns, in his and Morricone’s view. Not only was the action best served by music stripped to its bare lyrical and dramatic spirit, but sound, dialogue and music all had to be delivered in linear fashion, alongside very deliberate choreography and camerawork, in order to pace the story at a level to be fully internalized. Says Morricone: “If you respect the temporal nature of both film and music, you get the best results. Sergio had this intuition, and so for some scenes he left the music alone and gave it time to express itself…” (Morricone/Frayling 97). While this technique obviously does not effect realism, to Leone his films were something to be labored over and treasured, and to that end he isolated discrete sounds “in a way [that] it becomes a kind of fantasy” (Morricone/Frayling 96). Gun shots become hyper-real when compressed and coated in reverb; just as such the traditional classical forms of Morricone’s music playing themselves to fruition provide an argument in favor of fantasy in the textual reading of death scenes. Though flashbacks provide the realist answer to addressing memory in film, they do not provide any of the mystery that a “musical flashback” can. Avoiding the visual flashback with Jill, leaving her thoughts to music, is what affords her character a more psycho-analytical critique, and saves the best flashback for the denouement of the film. The real enemy of Frank, Cheyenne and Harmonica is capitalism, embodied in the train baron character of Morton. So while Leone was critical of America on the one hand, he wanted to express the last gasp of a time when beauty was to be found in simplicity. While Frank is a true enemy, he is a sympathetic one, overshadowed by a modern age. All that’s left is for him to play out the code of honor between men, that is, to “never run out on an opponent”, and duel face-to-face, counter to the sneakier practices of the new capitalist era (Fistful-of-Leone.com). This is why the bad guys are portrayed so heroically in the music, the ascending horn calls - the dirge-march rhythms, the dramatic melodic leaps - for they are being done in by a greater enemy, one without a face but with an invisible hand. In their final conversation before the duel, Frank and Harmonica belie an understanding that they already know what is to happen, in a manner much akin to staging a classical Greek tragedy:

H: So you found out you’re not a businessman after all. F: No, just a man. H: An ancient race. Other Mortons will come and kill it off. F: Nothing matters now, not the land, not the money, not the woman… I came here to see you, ‘cause I know that now you’ll tell me what you’re after. H: Only at the point of dying. F: I know.

Matthew Steckler Film Music: Historical & Aesthetic Perspectives

Professor Sadoff November 6, 2008

Counting before and after this dialogue, the conclusion of the film repeats the Frank and Harmonica cue (titled “As A Judgment”) three times, a majestic send-off signaling the death of an era. That music which stylized the postponement of progress (represented in Brett McBain) in the beginning now underscores the cowboy’s final stand, before progress will at last take over. Thus, in Once Upon a Time in the West we have a story that explores “the relationship between popular fictions (‘Once Upon a Time…’) and their historical basis (‘…there was the West’), at the same time lamenting the end of the golden age, and of the Western as fable” (Frayling 251).

Matthew Steckler Film Music: Historical & Aesthetic Perspectives

Professor Sadoff November 6, 2008

Matthew Steckler Film Music: Historical & Aesthetic Perspectives

Professor Sadoff November 6, 2008

Matthew Steckler Film Music: Historical & Aesthetic Perspectives

Professor Sadoff November 6, 2008

Matthew Steckler Film Music: Historical & Aesthetic Perspectives

Professor Sadoff November 6, 2008

Matthew Steckler Film Music: Historical & Aesthetic Perspectives

Professor Sadoff November 6, 2008