Alberto_Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

-

Upload

matteomandarin3522 -

Category

Documents

-

view

220 -

download

0

Transcript of Alberto_Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

7/24/2019 Alberto_Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/albertoburning-dwelling-thinking-mute 1/12

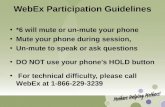

13/01/2015 20:58Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

Page 1 of 12http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/burning-dwelling-thinking#

ARTICLES

BURNINGDWELLINGTHINKINGBy Alberto Toscano , 13 January 2015

Activism / AntiCapitalist / Communism / Occupations / Social Movements / Technology / Theory / Continental / Crisis

Image: Gec, Il Quarto Stato, Val de Susa, Italy

After the Insurrection that was to come The Invisible Committee’s À nos amis assesses the defeats and

'permanent catastrophe' which never stopped. Alberto Toscano’s extended review, ahead of the book’s

English translation, seeks points of agreement among the peaks and pitf alls of a relentless metaphysicalattack on network power

It is the rule of European culture to organise the death of the art of living.

– Jean-Luc Godard, JLG/JLG – Self-port rait in December

Agir en primitif et prévoir en stratège.

– René Char, Feuillets d'Hypnos

1. A theory of revolution is a balance-sheet of its defeats. That much transpires from the first pages of À nosamis/To Our Friends (English translation forthcoming in April from Semiotext(e)), setting it apart, notwithstanding the

continuities of tone and targets, from The Coming Insurrection. Where in the latter, to recall the EighteenthBrumaire, phrase had prophetically anticipated its content, now the content has outstripped the phrase. The

insurrection came and was beaten back. Yet it is still coming. But the order of urgencies has shifted, the poetry of

the imminent future largely making way for the prose of the recent past. We have been defeated. But we are

everywhere. Stability is dead. Capitalism is disintegrating. And yet it reproduces itself – as a catastrophe inpermanence.

7/24/2019 Alberto_Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/albertoburning-dwelling-thinking-mute 2/12

13/01/2015 20:58Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

Page 2 of 12http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/burning-dwelling-thinking#

2. The mood is not so much of slow impatience, as of its inverse, a hastening patience, a planetary horizon distilled

into action in situ, not required to wait for any appointment with history, any serendipitous crossing of capitalism's

curvature. A theory of revolution should bind together a portrait of the conjuncture, a sounding of the tendency, the

naming of enemies, the gathering of friends. ‘Who are our enemies? Who are our friends?’ are the very first lines of

the first volume of Mao Tse-tung's Selected Works. From the title on down, this ‘classical’ question resonates

throughout To Our Friends. But it is precisely in the ‘we’, in what the linguist Roman Jakobson tellingly dubbed a

shifter – a part of speech whose referent is only stabilised by a message's context – that this call is less univocalthan may at first appear.

3. That is not so much a product of the authors’ incomplete anonymity. The reckoning with counter-revolution

demands reflexivity, subordinating the supremacy of foes to the weakness in ‘our’ forces. The initial impression is

then that of an all-too-welcome self-criticism. But there is a crucial gap between the ‘we’ who faltered and the ‘we’

who writes. The political automatism of crisis, for instance – here predictably pinned onto a readymade apocalyptic

Marxism – was certainly not a sin of the Invisible Committee's previous profession of communist faith. And the

suggestion that what blocks ‘us’ is the stubborn resilience of the ‘Left’, of a whole habitus of militancy that

undergirds Leninist, social democrats, anarchists and many ‘occupiers’ alike, was no doubt one of the caustic

leitmotivs of The Coming Insurrection. Likewise, in lambasting the whole repertoire of consensual antagonism, fromthe human mic to the wavy hands, it does not seem that the authors are, to paraphrase Fortini’s poem, ‘Translating

Brecht’, writing their own names in the list of their enemies. And perhaps they couldn’t, without troubling the rhetoric

of secession and authenticity that pervades their text.

4. Considering the Committee’s considerable capacity for polemical incision, for sallies of devastating Kultukritik , itis a shame that less restraint is not exercised in matters of style, which is also politics. The final envoi in verse,

which almost seems to apologise for the bracing analysis that preceded it, is a case in point. We could also adduce

such dismayingly confident declarations as ‘our margin of action is infinite, historical life stretches out its arms to us’

(p.39 this and all subsequent translations mine). ‘We’ are certainly not everywhere, conspiring, as the authors

hopefully report. It is with undue confidence – and against the grain of its picture of the epoch as one of untoldmetaphysical and anthropological degradation – that To Our Friends presents the popular wisdom of the day in the

Argentinian adage, ¡Que se vayan todos! If that is so, it is only to the extent that this scorning of those who govern

us is also a property of the right, and handled by it with much greater assurance than the Party of Equality could

ever muster. Likewise, it is bending the stick too far to project into Occupy Wall Street – a movement whose forays

into the revolution of everyday life were comparatively timid – the idea of a ‘disgust’ with life today. Wouldn’t it be

more useful, beyond the ‘existential’ epiphanies that might overtake us in our groups-in-fusion, to gauge how littlehabits and psyches have been truly ‘revolutionised’ in recent risings? Joining a communist party in the age of Stalin

no doubt involved far greater personal upheavals than participating in today's insurrections, which, for better or

worse, require far less thorough de- and re-subjectivations.

5. Fed up with every received philosophy of history and delusion of progress, To Our Friends tells us to refuse the

interpellation of the economic crisis. Behind this, however, is not a familiar nominalist option for which ‘crisis’ is but

an abstraction illegitimately foisted upon the real multiplicity of social life. Not only is it emphatically affirmed that the

happenings since 2007 are part of one ‘sequence’, ‘a single wave of uprisings that communicate among themselves

imperceptibly’ (p.14); insurrection itself is a kind of expressive totality: every individual surge carries ‘something

global’ (p.15). From Libya to the Ukraine, Tunisia to Wall Street, Notre-Dame-des-Landes to Oakland, the Invisible

Committee are vigorously inclusive when it comes to the sites of contemporary antagonism, of what they want to

reveal as a single (if not actually unified) revolutionary process. But the ensemble of insurrections does not express

or even respond to a capitalist crisis. Indeed, the dominant discourse of crisis, with its invocation of the

ungovernable, itself stands revealed as a ruse of government. That is why in the final analysis ‘there is no “crisis”

from which we need to exit, there is a war that we need to win’ (p.18). The absence of critical ‘points’, the everyday

experience – both enforced and disavowed by the powers-that-be – of the endlessness of crisis, is transmuted inthese pages into the horizon of a total negation. While crises financial and political are not simply discounted, they

are in the end mere epiphenomena of a properly civilisational, metaphysical crisis. A crisis of presence. If we wished

7/24/2019 Alberto_Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/albertoburning-dwelling-thinking-mute 3/12

13/01/2015 20:58Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

Page 3 of 12http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/burning-dwelling-thinking#

to be paradoxical, we could say that what unites the current sequence of revolt, what historicises them, is the fact

that they no longer pose the problem of a discontinuity in history, but a discontinuity from history, the history of the

West. In the propositions of To Our Friends, it is difficult to shake the impression that what is being demanded is

affinity, assent. No argument or analysis is advanced (nor could it be) for the overtaking of ontic crises by a veritably

ontological one, and if you find the ontalgia (to borrow a neologism from Raymon Queneau) transpiring from

sentences like ‘we have lost the world’ either inimical or incomprehensible, you will know that you can only conspire(breathe with) so far and no further – perhaps, you are not really a friend. The matrix of a romantic anti-capitalism is

irremovable, no matter how much it may be offset by an axiomatic agonism (according to which ‘civil war’ is

inexorable, the attempt to expunge it both delusional and debilitating). True life, the fight against the ‘civilisation of alienation’, the loss of the world – these are the watchwords of the Invisible Committee. Perhaps an allergy to the

kind of urge for authenticity that pervades To Our Friends is but a mark that one remains a ‘Westerner’ (a category

the authors dubiously note is indifferent to colour, p.33), unable to join the ‘war’ of the earthlings [Terriens] against

Man (p.33). There is portentous, left-Heideggerian ring to such talk – leavened, perhaps, by quoting from World War Z (p.39). Though the authors speak of ‘the catastrophe that we are’ (p.29), it is merely as a prelude to an all too

quick desertion. In this angry leave-taking from millennia of metaphysics, the authors risk dragging in their train

more humanist detritus than they suspect. Presence is such a Christian word.

Image: Graffitti against the proposed airport in Notre- Dame-des-Landes, unknown location or date

6. It is unfortunate that the name of ‘life’, that resilient repository of pseudo-concreteness and false immediacy,

wasn't handled with as much suspicion in these pages as the quotidian infrastructure of late capitalism, from high-

speed trains to iPads. One may not be able to employ the latter with impunity, but neither can one dive with both

hands into the reservoir of life-philosophy and vitalism without sowing more confusion than anyone can currentlyafford. There is nothing to celebrate about life nor to condemn about calculation, as such. Such a position is but the

obverse of reification, its product and its complement. To Our Friends, as behoves an insurrectionary theory of

defeat, is a much more sober text than The Coming Insurrection, and the better for it, but it still can’t resist telling

itself stories it must doubt deeper down. What it perhaps doesn’t reckon with is how similar it is in this respect to so

much of the contemporary radicalism it abhors, rarely capable of conveying enthusiasm without that false note of

exhortation. Today the most depressing texts are often the most euphoric.

7. I feel it necessary to mark this distance from the positions and poetics of To Our Friends to better address the

book’s pivotal question, that of organisation understood as common perception (p.17). One doesn’t really criticise a

manifesto or a call, especially when it is not addressed to you, but it may be possible nonetheless to makesomething of the moments of assent and dissent that such declarations elicit. So even if much of this perception is

not shared, the terms of the problem – what would it mean to forge a common perception – no doubt must be. For

7/24/2019 Alberto_Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/albertoburning-dwelling-thinking-mute 4/12

13/01/2015 20:58Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

Page 4 of 12http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/burning-dwelling-thinking#

the Invisible Committee, the organisation that the uprisings of 2011 and after lacked is thus not a party, not a union,

or a militia, but a perception. (Though the Committee would likely baulk at this, we are not a million miles from

Badiou’s translation of organisation as idea, or, in another register, Jameson’s cognitive mapping, both

understandable as varieties of class consciousness without a class.) A common perception is the marriage of ethics

and strategy. Here it is difficult not to hear the echoes of the later, defeated Debord, weighing up the spectacle’s

own conspiracies of reproduction through the lenses of Clausewitz (in Commentaries) and the damage done to life

and ethos (in Panegyric ). Unlike in Debord, the negativity of To Our Friends is more epidermal. How, otherwise,

could one write such disarming sentences as: ‘strategic intelligence comes from the heart’ (p.16)? This desire for

another life is also more prophetic than dialectical. In turn, the arche-politics of a planetary ethical revolt risksoverwhelming considerations of strategy, or calibrations of tactics. ‘What is at stake in contemporary insurrection is

the question of knowing what is a desirable form of life, and not the nature of the institutions that oversee it. But to

recognise this would immediately imply recognising the ethical nullity of the West’ (p.48). Surely a form-of-life can’t

be pried away from its institutions, at the risk of collapsing into that vitalist immediacy which has always served as

romantic anti-capitalism’s abiding temptation. If ‘the West’ (whatever it may be) is an ethical void, then we may just

have to be a little careful about carrying on with a political and philosophical discourse which doesn’t just borrow

wholesale from a recognisably Western ethical and philosophical grammar, but fails to subject it to determinate

negation. ‘Ethical truth’ (p.46), here articulated as the opposite of democracy – perhaps that too is a ‘Western’

concept... (So much would be suggested, for instance, by Viveiros de Castro’s enticing On the Inconstancy of theSavage Soul .) And precisely to the extent that current insurgencies haven’t , except fugitively, given rise to new

institutions, they have left the new life precisely as a matter of desire, which is to say of lack.

8. This ‘other idea of life’ (p.57) thus risks being nothing but an idea, of happiness and the good life, just as abstract

as the idea of communism. We might not have lost the world, but we have certainly lost many of the moral

economies that would make an ethical opposition effective. That is why it is striking that the question of how one

may produce, invent, experiment with other modes of living, while dismantling the current ones, receives relatively

scant attention in these pages – notwithstanding the several indications of where this other life may be painstakingly

constructed (in the struggle in the Val di Susa against the Turin-Lyon high-speed railway, in the one against the

Aéroport du Grand Ouest in Notre-Dame-des-Landes, etc.). Too quick to absorb the generalised negativity into its

project, To Our Friends stipulates that widespread condemnations of ‘corruption’ are a sign of this ethical turn of

antagonism (p.50). Yet, as it recognises in its provocative peroration against the Spanish label of indignado (‘He

postulates his impotence all the better to cleanse himself of any responsibility as to the course of things; then heconverts it into a moral affect, in a trait of moral superiority. He thinks he has rights, the sad creature’, p.56) this may

serve as a kind of exorcism, a way of calling ‘ourselves’ out of the moral and financial mire of the present, of

assuming the position of victim alone.

9. But something more precise and more severe is going in these pages, as they distil with combative acumen what

is at the core of the insurrectional criticism of the movement of squares: its fetishism of democracy. There are

refreshingly harsh moments here, as when the Committee reminds us that popular comes from populor , ‘to ravage,

to devastate’ (p.54), that an uprising is a plenitude of expression and a nothingness of deliberation. The contempt

that the latter term is held in (displaced by the non-instrumental communication of friendship, with shades of

Maurice Blanchot) signals the wish, beyond the illusory drift of the first person plural, to divide the ‘we’ into anantagonistic detachment, on the one hand, and a petty-bourgeois impasse, on the other. No doubt, to the extent

that in its moments of non-confrontation much of the spontaneous political philosophy of the ‘movement of squares’

is broadly ‘democratic’, it also sets the stage for another ‘civil war’, a war between notions of the popular. It’s a

shame that To Our Friends opts to castigate Hardt & Negri, or Hessel, or the common sense of assembly politics,

rather than squaring up against the politically serious modalities of contemporary radical reformism, such as Syriza

or Podemos. For these latter, when all’s said and done, must be its enemies, to the very extent that they impose a

political strategy, grounded on democracy and deliberation, that can only impede the surge of the other life, the

irruption of ethical truth. Surely, from the Committee’s vantage, such a channelling of refusal into a project of power

could only signal disaster? Has one square divided into two? On the one side, ‘the crash against the real of the

cybernetic fantasy of universal citizenship’; on the other ‘an exceptional moment of encounters’ (p.58). The

pragmatic pedants of ‘micro-bureaucracy’, be they Trotskyist or anarchist, square off against the partisans of an

ethical revolt. The negative phenomenology of the assemblies, with its bracingly dark humour, testifies here to alived experience of disengagement and frustration.

7/24/2019 Alberto_Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/albertoburning-dwelling-thinking-mute 5/12

13/01/2015 20:58Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

Page 5 of 12http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/burning-dwelling-thinking#

Image: Oakland, 2011

10. The diagnosis is an existential one: the fetishism of the general assembly and the political affect of indignation,

voiced in the ‘formless language of separated life’ (p.61), stem from the fact that an assembly can only come out

with what it already contains, and if what it contains is the seriality of a damaged postmodern ‘life’, then the result

will be naught but collective impotence. And yet, if the squares are two-in-one, for every pseudo-antagonistic

paroxysm of democratic hysteria there are shoots of a new life, able to ‘inhabit the uninhabitable’ metropolis (p.61),

to dwell [habiter ]. It is not in the anxieties of direct democracy but in the self-organisation of everyday life that these

movements and insurgencies score their real political victories. The lessons are again metaphysical in scope, as the

insistence on ‘dwelling’ might suggest – here harmonising with left-Heideggerianism more than with the practical

utopias of habitation of Lefebvre’s recently published Toward an Architecture of Enjoyment . That anxious

compulsion to repeat which is voting is surpassed by ‘an unprecedented attention to the common world’, which

receives a kind of philosophical imprimatur: ‘a regime of truth, of openness, of sensibility to what is there’ (p.63). It is

interesting to see how the collective assumption of the requirements of social reproduction (not all of course,

protesters weren’t running the sewer systems, the water supply, or sundry facets of the logistical state) is here taken

as the material sign of a revolutionary present. It is perhaps a ‘Western’ peculiarity to be thus amazed at self-

organisation, but its an amazement that might not be in the end so philosophical, if it leads us to ignore that this

‘movement communism’ (to use Badiou’s term for the same phenomenon in The Rebirth of History ) is politically

indeterminate. Social reproduction and self-defence are also the purview of far-right militants or religious

conservatives (as evident from Maidan to Tahrir), and unless we think that taking over what has been monopolised

by the state is as such emancipatory we may have to recognise that neither ethics nor reproduction, and certainly

not ‘life’, are capable of rendering obsolete the moment for politics, or indeed deliberation – which is certainly notreducible to sterile assemblies and wavy hands.

11. The truth of democracy, the Invisible Committee tell us, is not the state or the law, it is government. In the

political-metaphysical horizon of To Our Friends, democracy is the ‘truth’ of all forms of government, insofar as the

identity of governor and governed is government ‘in its pure state’. The present would then appear as a kind of

apotheosis of the cybernetic rule which had already been compellingly theorised by Tiqqun. The conditioning of this

‘great movement of general fluidisation’ (p.69) by the imperatives of accumulation stands in the rather distant

background, so much so that at times one suspects that a properly ontological fate is at work, and agency has been

volatilised. Though power is invoked more than theorised, the Committee nevertheless raises an extremely urgent

and painfully concrete question: what allowed the revolutionaries in Egypt, Tunisia and elsewhere to be ‘played’ byestablished political forces, turned into vanishing mediators, retroactive stage armies for settling accounts in the

corridors of power? The answer is deceptively simple: if you demand a destitution (of established power) but don’t

7/24/2019 Alberto_Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/albertoburning-dwelling-thinking-mute 6/12

13/01/2015 20:58Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

Page 6 of 12http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/burning-dwelling-thinking#

have the force to organise, organised forces will manipulate you and the very process of destitution. Or, in an

elegant dictum: ‘A movement that demands always has the lower hand against a force that acts’ (p.72). Even more

pointedly, the Committee suggest one abandons the ‘fiction’ of a dialectic of constituent and constituted power, in

which the popular act of destitution could be absorbed into the dynamics of legitimation, eliding the ‘always sordid

origin of power’ (p.73). (It might be noted that the abandonment of any such dialectic, and of any attendant

conception of legitimate power ruins any available conception of revolution, including, it could be argued, anarchist

ones. The authors, for reasons that may be more aesthetic or ethical than they are properly political, still insist on

calling themselves revolutionaries.) The conclusion is unimpeachable: ‘Those who have seized power project back

on the social totality that they now control the source of their authority, and will thus legitimately silence it, in its ownname’ (p.73).

12. To abandon the dialectic of the constituent and the constituted, and its hypostasis of contingent forms of

government (the Republic) is thus to rethink revolution as pure destitution – that which deprives power of its

foundation without creating a new one (‘destituent power’ is the last word, so to speak, of Giorgio Agamben's HomoSacer series, closing its last volume, The Use of Bodies, and his influence is palpable in these pages). Insurrection

here is a great revealer, simultaneously manifesting the metaphysical vacuum of power and its contingent roots in

the vile particularities of policing and privilege. I sense that the authors don’t consider it a paradox to link the

Heideggerian sweep of their anti-history of the West with this rather Durrutian conclusion: ‘All bastards have an

address. To destitute power is to bring it down to earth’ (p.75). But the destitution of governing power is also thedestitution of popular power. Not the least corollary of this approach is the call to ‘give up on our own legitimacy ’(p.76). This is an acute challenge, to be heeded at the very least by remaining vigilant to the ease with which

supposedly antisystemic movements reproduce, and at times revitalise, the very coordinates of their subjection.

13. But the Committee don’t heed their own injunction. Instead, they consistently shift the locus of legitimacy, which

is to say of truth, from the practical to the metaphysical. From what they call their ‘other plane of perception’ (p.78),

they posit that the problem of government, and the negative political anthropologies it implies, can only be posed

once a void has been created between beings. To exit the paradigm of government is to enter that of ‘habitation’, a

relational ontology of plenitude in which ‘each of us is the place of passage and knotting together of a welter of

affects, lineages, histories, significations and material flows that exceed us. The world does not surround, ittraverses us. What we inhabit inhabits us’ (p.78). Organisation and strategy would thus come down, in the last

instance, to the Gestalt switch that allows us to stop seeing things, subjects and bodies, and start living through

forces, power and connections: ‘It is through their plenitude that the forms of life achieve destitution’ (p.79). For

such a caustically critical collective, it is perplexing that the Invisible Committee wouldn’t recognise how much they

have joined an all-too-common contemporary tendency: to deny the autonomy of the political only to accord it to a

life and a being equivocally politicised. It might be argued that they have not renounced their own legitimacy, they

have hypostasised it, in life itself.

7/24/2019 Alberto_Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/albertoburning-dwelling-thinking-mute 7/12

13/01/2015 20:58Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

Page 7 of 12http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/burning-dwelling-thinking#

Image: 'Capital survives / if the commodity runs / if the commodity runs life dies / Let's block everything'

14. Headed, like the other chapters by the photograph of a graffito – this one from the Susa Valley, declaiming in

Italian: ‘Power is logistical. Block everything!’ – the section on infrastructural power is the strategic heart of the book,

and arguably the one least mortgaged to a metaphysics of insurgent life. Never ones to let a sweeping declaration

go to waste, the Committee start from the visible performances of insurrection from 2011, all those assaults on the

symbols of power which are defended by the ‘forces of order’ with a fierceness the authors think is proportionallyinverse to their significance: ‘Power no longer resides in institutions’ (pp.81-2). They are but ‘lures for

revolutionaries’ (p.82). It might be retorted that symbolic efficacy hasn’t entirely gone away. Or, conversely, that the

‘theatrical’ character of power has been on the wane for long, centuries even. Strong periodisations are arguably

indispensable for any common perception to emerge, but it is surely historically disorienting to posit a passage from

institutions to infrastructures. Not only have the institutions of the state always depended on infrastructural power –

from the debates on the hydraulic bases of ‘Asiatic despotism’ to Robert Linhart’s brilliant excavation of the logistical

tragedies of Bolshevism in Lenin, the Peasants and Taylor – but contemporary infrastructures, from metro systems

to intermodal transport, are institutions, replete with bureaucracies, measurements, agencies, rituals, lobbyists, and

so on. They don’t make or rule themselves. One can accept the salience of the infrastructural to recent strategies of

power and opposition – as well as to the readjustments in the mode of production – without accepting that

institutional-representational power is but a smokescreen. In a passage like the following, logistics, like self-

valorising capital for value-theorists or the police for anarchists, can turn into a veritable fetish:’The nature of contemporary power is architectural and impersonal, not personal and representative’ (p.83) (I guess we can delete

the addresses of the bastards after all, as they don’t much matter in the end.) The acute descriptions belie the

epochal narrative. The position of a purely cybernetic power, without a secret other than its functioning, immanent to

apparatuses like ‘the blank page of Google’ turns out to be the site of ! political decisions: ‘He who determines the

arrangement of space, who governs milieus and environments, who administers things, who manages access,

governs men’ (p.84). This is well said, but there’s no reason why this agency should be thought of as transcending

institutions (one can prove so much just by following along with Donald MacKenzie’s account of the material and

juridical genesis of high-frequency or algorithmic trading). This also holds for the way in which the contemporary

‘governance’ of capital produces ‘zones’ beyond the nation, subjecting the very notion of ‘society’ to a violent

fluidisation (p.185).

15. That said, To Our Friends synthesises with flair a feeling diffuse among contemporary struggles, which we could

term as the demand for a political materialism that takes infrastructure as its field and target: ‘Those who wish to

undertake any action against the existing world, must start from here: the real structure of power is the material,

technological, physical organisation of this world’ (p.85) But I don’t see why it’s necessary, other than for rhetoric’s

sake, to declare immediately thereafter: ‘Government is no longer in government’ (p.85). This may be true in terms

of long-held political illusions that neglected the materiality and political economy of the state. But it is impossible to

grasp (and to intervene in) infrastructures without realising how the material, technological and physical

organisation of this world also requires a mind-boggling array of institutional operations, and not a few

governmental ones. To neglect law and politics as constituent of such infrastructural power would be a major

strategic blunder. ‘Political constitution’ isn’t laminated onto ‘material constitution’ without remainder.

16. To Our Friends uses this concept of infrastructural power to account for how domination today has moved from

the symbolic to the environmental, while policing has been accelerated in its pervasiveness precisely by becoming

the guardian of a power that lies, so to speak, all along the network. Not least of the virtues of the Committee’s

attention, of its perception of this ‘logistical revolution’ in the arts of domination, is how it accounts for the impasses

of much contemporary revolt. As they laconically observe: ‘you do not criticise a wall, you destroy it or tag it’ (p.86).

Against the broken-homogeneous space of the metropolis, ‘desert and existential anaemia’ (p.88), rise places of

common joy (Gezi, Puerta del Sol, etc.) in which we can gauge the ‘intuitive link between self-organisation and

blockage’ (p.89). But the landscape of capital too has shifted, as the workers’ prison and fortress, the factory, has

transmuted into a ‘site’, a logistical link. In a couple of clipped pages (pp.91-2) the authors try to summarise and

dismiss much Marxian debate, generally crystallised around the second volume of Capital , but also the discussionof the general intellect in the Grundrisse. It would be churlish to engage in philological exercises here, but it is worth

noting, in terms of its political upshots, that the lesson drawn – besides the one of the obsolescence of value theory

7/24/2019 Alberto_Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/albertoburning-dwelling-thinking-mute 8/12

13/01/2015 20:58Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

Page 8 of 12http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/burning-dwelling-thinking#

– is that of an indiscernibility between spheres of production and reproduction. It is a dialectical irony, not noted by

the authors, that infrastructural changes produced as strategies in the class struggle – to fragment the power of

transport and extractive workers, in particular – should give rise to a situation of expressive totality, where any

logistical attack is an attack on the system as a whole.

17. ‘To physically attack these flows, at any point whatever, is therefore politically to attack the system in its totality’

(p.93). This is hopeful, but weak. A system is only politically attacked in its totality if there is a totalising intention or (preferably and ) a totalising effect. Precisely because such networked systems are strategically designed to

minimise contagion, depending on the fragmentation of labour and the maximisation of resiliency, as much as on

homogeneity of standards and intermodality, nothing is less sure than the notion that to block one flow is virtually to

block them all. The Committee entreat us to see ‘each attempt to block the global system, each movement, each

revolt, each uprising, as a vertical attempt to stop time, and to bifurcate in a less lethal direction’ (p.94). This

arresting Benjaminian image unfortunately generates in enthusiasm what it blurs in understanding, since we haven’t seen any attempt to block the global system as such (whatever that may mean), but more importantly because such

a vision of metaphysically expressive revolts runs against the strategic question of how revolts against logistics

could be made antisystemic. To presuppose that blockages are already as such antisystemic is not just to ignore

how they’ve long been tactics of perfectly ‘reformist’ movements (or even of reactionary ones, as in the truckers’

strikes in Chile, to which Allende’s government responded with a! cybernetic system), but to fantasize that a tactic

can in itself be a strategy. Later in the book, the authors provide the blunt correction to this misstep: ‘Sabotage hasbeen practised by reformists as well as Nazis’ (p.144).

18. The chapter on blockages concludes with some astute reflections on the question of knowledge. Grounding

itself on the very classical assumption that the weakness of struggles is a product of the absence of a credible

revolutionary perspective, and not vice versa, the Committee pose the problem of the present as that of a

revolutionary strategy aimed not against power’s representatives but against the ‘general functioning of the social

machine’ (p.95), on which we depend for our survival . Here the reflexive negativity of struggle (we are our own

enemies) takes on a material cast (our enemy is our life-source) and poses a practical, experimental question: how

could one de-link from such infrastructural power without incurring the paralysing menace of scarcity? In other

words, how can sabotage not be primarily against oneself? The severity and sobriety of the following statement iswelcome: ‘as long we won’t know how to do without nuclear plants and dismantling them is to be a business for

those who wish them to be eternal, to aspire to the abolition of the State will continue to raise a smile; as long as

the horizon of a popular uprising will mean the certain shortage of medicines, food or energy, there will be no

resolute mass movements’ (p.96). From here comes the call to revive the inquiry as a tool bringing together

strategy, knowledge and political (and ethical) recomposition. As they write, ‘there is no point in knowing how to

black the infrastructure of your enemy if you do not know how to make it function, if needs be, in your favour’ (p.99).

It is interesting that the moralistic tonality of previous references to the good life fades here, replaced by a more

attractive vision of another life as founded on the ‘passion of experimentation’, on a ‘technical passion’, the

‘accumulation of knowledge’ (p.96), without which there can be no serious return of the question of revolution. It’s

perhaps testament to our inverted present that the most realist and materialist moment in this tract, the call to

‘aggregate all technical intelligence into a historical force and not a system of government’ (p.97), taking leave of

our deep ignorance about our material conditions, should sound the most Utopian.

19. Where the material and energetic infrastructures of capital’s reproduction afford an imagined reappropriation, at

least a partial one, those of ‘communicative capitalism’, namely Facebook and Google, are but most baleful

realisation of the managerial lust of cybernetics. Some of these pages, as they scrape around the web’s military and

financial plumbing, can be read with gusto, but it is difficult to shake the feeling that they are in the end redundant,

echoing a critical common sense – which of course doesn’t stop (almost) anyone from reproducing (themselves

through) these speculative-exploitative dispositifs. That the misery of cybernetics is what will make it collapse in the

face of ‘presence’ seems wishful thinking. More suggestive, though somewhat rushed, is the anthropological claim

that social media evince the outstripping of technics by technology, defined as the ‘expropriation from humans of

their different constitutive techniques’ (p.125). Continuing the extended Heideggerian pastiche, whereas theengineer is the chief expropriator of technics, the hacker embodies the ‘ethical’ (in the sense of ethos) facet of

technics. He is the figure of experimentation understood as living what is ethically implied by a given technique. For

7/24/2019 Alberto_Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/albertoburning-dwelling-thinking-mute 9/12

13/01/2015 20:58Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

Page 9 of 12http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/burning-dwelling-thinking#

all the calls to abandon the West, this ethics of knowledge has a distinctly Enlightenment flavour, wherein

understanding how the apparatuses surrounding us work, prying open the black box, entails an ‘immediate increase

in power’ (p.127). The Committee are careful though not to drag the regressive assumptions of libertarian

individualism into this figure, and riffing on the etymological affinities of ‘friend’ and ‘free’, we are told that the

freedom borne by the hacker is a collective, a transindividual one: ‘I am free because I am bound’ (p.129). The

fetish of unbound freedom (and free speech) is thus a necessary sacrifice if hackers wish – do they? do we want

them to? – to ‘become a historical force’ (p.129).

20. The more we advance into this tract, the more the call for a common perception and the enumeration of mirages

grows louder. Though its insistence on ethical truth would seem to militate against it, To Our Friends is not just a

critique of the ideologies of recent movements, it is also a call for an ideology. The meagre and bitter fruits of the

inspiring mobilisations in Greece teach us that ‘without a substantive idea of what a victory would be, we can only

be vanquished’ (p.136). By a somewhat sketchy detour via the Ancient Greek ‘origin’ of politics, we come to the

repudiation of the paralysing face-off of radicalism and pacifism. Neither strategic nor conjunctural, the analysis

here is entirely philosophical. War is defined as ‘not carnage, but the logic that presides over the contact of

heterogeneous power’ (p.140). A rather bloodless, metaphysical definition, aimed at declaring the inanity of those

who wish to ban war from the socius. But without the fact of killing, in quantities industrial or artisanal, why not stick

with ‘conflict’, ‘agonism’ – as so many of our political theorists do? Is there an extra frisson of authenticity in all this

talk of civil war ? Despite the weakness of this slogan, the portraits of pacifist and radical are ably executed,especially the latter, with his ideological praise of violence, his neglect of strategy and privatisation of activism as ‘an

occasion for personal valorisation’ (p.144) (I’m sure every reader has assembled a rather ample line-up of such

‘radicals’ in their own mental theatre). The phenomenology of the ‘small terror’ of ‘radical milieux’ is also painful in

the realism of its observations: ‘A vertigo takes over a posteriori anyone who has deserted these circles: how can

one subject oneself to such mutilating pressure for such mysterious stakes?’ (p.145) Against the radical’s

‘extraterrestrial politics’, bringing insight from outside and above, To Our Friends again sounds the note of ‘attention’

– a promising if problematic one, since it depends on a somewhat vague image of the revolutionary’s ‘sensibility’, of

the production of acts that are slightly ‘ahead’ of the movement but whose appositeness is decided by the state of

the movement itself. (In passing, it is odd that writers so taken with the idea of civil war should so easily slip into the

left jargon of ‘the’ movement.)

21. ‘Life is essentially strategic’ (p.150). Having mobilised the problematic martial metaphors of immunity a few

pages before, and seeking a fusion of strategy with ethics, this declaration should not come as a shock. What is

more striking perhaps is that in seeking to develop a ‘civil concept of war’ (p.150) the authors draw with such glee

from the archive of contemporary counter-insurgency. Nothing wrong with learning from the enemy, of course, but in

these long citations without commentary, we miss the opportunity of truly thinking (following the work of Laleh Khalili

and others) through how the gendered and racial axes of social reproduction are entirely crucial to the sociology of

counter-insurgency, and to reflect on how those identities and resources could be neutralised or mobilised in a ‘civil’

politics of war. What’s more, to present the ‘epoch’ (it will have been one of the book’s main aims, as it was of its

prequel, to assert in no uncertain terms that this is indeed an epoch) as the ‘race [between] the possibility of

insurrection and the partisans of counter-insurrection’ (p.155) is to sideline the quotidian character of social

reproduction and its logistics, the low-intensity warfare that accompanies the organisation of exploitation andexclusion, and to draw too much sustenance from the scenarios of global insurrection that pepper the reports of the

CIA and other such bodies – which after all depend on these scenarios to make themselves and their military-

industrial complex necessary. It is heartening nonetheless to see the authors vigilant as to the temptation to flip

counter-insurrectionary theories into insurrectionary ones. Their alternative is gnomic if suggestive: ‘We need a

strategy which doesn’t target our adversary, but his strategy, and turns it against itself’ (p.157).

22. The problem is that the premise of this dictum, the ‘ontological asymmetry’ between insurgent and counter-

insurgency experts, is based on a hopeful but massive over-estimation of one’s own threat or power: ‘We

revolutionaries are both the stakes and the target of the permanent offensive that government has become’ (p.161).

A momentary threat, yes, a permanent nuisance, surely, but the target? This is highly doubtful – as is the later statement that the global counter-revolution that took 9/11 as a ‘pretext’ was a political response to ‘anti-

globalisation’ – nonetheless anatomised as a movement of the planetary petty-bourgeoise which disappeared in its

7/24/2019 Alberto_Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/albertoburning-dwelling-thinking-mute 10/12

13/01/2015 20:58Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

Page 10 of 12http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/burning-dwelling-thinking#

very realisation (p.226). In this imaginary projection of the ‘we’, To Our Friends risks repeating one of the rhetorical

traps of the very sectarianism it is trying to escape – the idea that power is just a reaction-formation against our own

formidable threat. But the reproduction of a capitalist society is a much less circuitous and martial thing than that, its

violences more distended if not less profound. To treat all social life as a battleground might be galvanising, but it

remains an error. More interesting – because less metaphysical, more strategic – is the warning not to allow

government to produce one as a radical subject (be it ‘IRA’ or ‘Black Bloc’, to use their examples), as well as the

unexpected turn to the Palestinian resistance for a ‘diffuse’ and ‘irreducibly plural’ image of struggle (p.167). But

then we fall back again on that warm soil of legitimacy, ‘life’, from which (in one of the more dubious lines in the

book) ‘emanate both the identification of the enemy and effective strategies and tactics’ (p.165). And so strategycollapses into homily: ‘To dwell [habiter ] fully, that is all that one can oppose to the paradigm of government’ (p.165).

That said, the more demotic translation of this passage certainly carries a not insignificant truth-content: ‘Those with

shitty relationships will only be able to have a shitty politics’ (p.167).

23. Politically man dwells, then. But where? In a ‘local’ which repudiates all ‘localism’ – the Committee are rightly

unsparing in their critique of that evergreen temptation – an everyday life of territories in struggle whose consistency

is drawn from these struggles themselves. Feeling flippant, one might call this – recalling the Guevarist practice

theorised by Régis Debray – a foquismo without a party an army or a jungle. Rather than localism, localisation then,

that very activity of cognitive mapping – ‘following the connections from a stock-exchange floor down to the last

fibre’ (p.192) – which crowned the account of the politics of blockage, of counter-logistics. When aiming at theideologies of the contemporary left, the Committee’s aim is often true, and their distancing from the way in which

‘local struggles’ are often made to corroborate a consoling view of underlying sociability or communism (one from

which it might be suggested they are not entirely immune) hits the mark. But the way to avoid these ideological

pitfalls again seems to mean resorting to an extreme abstraction that wants itself to be the most concrete: ‘living life’

(p.195), the ‘experience’ of relations, friendships, proximities and distances. Can we put such trust in experience?

Isn’t it a paralysing fantasy to think that all of our experiences are to be carried into struggle, that all life is ‘in

common’ – a fantasy that can grow boring or sinister when these common experiences become institutions, rituals,

structures? (And how could they not unless we think that politics can be radically de-instrumentalised, de-reified into

a relentless flow of immediacies?)

24. Though they recoil at the term, there is an institution advanced here, that of the commune. Not a form of

government, a body politic, but nevertheless an institution, defined by the authors themselves as ‘a pact to face the

world together’ (p.201), and more ontologically as ‘a quality of relation and a way of being in the world’ (p.201). The

nods here are many: not just to 1871, but to Huey P. Newton, Kwangju and Gustav Landauer. Striking is the spatial

grammar brought into relief here: the commune is ‘a certain level of sharing [ partage] inscribed territorially’ (p.203).

The war against quantitative, calculating abstraction continues: ‘By its very existence, [the commune] breaks up the

management of the spatial grid’ (p.203); it is a ‘concrete, situated rupture with the global order of the world’ (p.204).

Again, the expressive totality looms large, the metaphysical stipulation that a rooted break is also a planetary one.

This is curious if we think that the global, the planetary, is a product of abstraction, of science and capital and

colonialism. Dwelling globally would seem to be a contradiction. (And ‘the’ commune could also be regarded as an

abstraction of incommensurable forms of commonality, which could only be projected as universal from the

heartlands of abstraction.) The solution is a heterodox federalism: the commune must both hold fast to a territorialreality heterogeneous to the system, and draw links and solidarities with other local realities, lest it turn into a sterile

or besieged enclave, or wander homelessly. The commune is here emphatically not a taking charge of the common,

a new legal form for appropriation, however egalitarian, it is ‘a form of common life’, a ‘common relationship to what

[communes] cannot appropriate to themselves’, the res communes, the ‘world’ itself. It is also an effort to abolish the

needs born of the world’s privation (in the authors’ rather Rousseauian universal anthropology) for the sake of a

profusion of means. In this merrily anti-historical-materialist horizon production is but a by-product of a ‘desire for

common life’. Inverting the Chinese slogan, we could say: ‘Production last!’ But ‘fecundity’, which is what the

commune organises, beyond economy and exchange, is first. It is what allows the Committee to hopefully declare:

‘we can organise ourselves and [!] this power is fundamentally joyous’ (p.221). Common life as the life of the

commune also replicates the expressive structure which pervades To Our Friends: ‘In each detail of life the whole

form of life is at stake’ (p.218). (One may be forgiven for finding this living without remainder claustrophobic,

superegoic.)

7/24/2019 Alberto_Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/albertoburning-dwelling-thinking-mute 11/12

13/01/2015 20:58Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

Page 11 of 12http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/burning-dwelling-thinking#

Configure block

25. At its strategic conclusion, like many tracts of the left, To Our Friends is suggestively vague. (It would be aninteresting exercise in militant iconoclasm to strip anarchist and Marxist essays of their final paragraph. An

anthology of them would certainly be indigestible.) Yet again, in the absence of a determinate target it is to the

elusive concreteness of ‘life’, of ‘where one is’ that the text turns, to the promissory empiricism of enquiries,

conspiracies, and local consistencies, and to the general question of alliances, here nicely articulated as translation.

In asking how to build a force that is not an organisation, the move is also to warm, concrete abstractions, but

abstractions nevertheless – and ones whose political valence is difficult to think as univocal: the increase of ‘power’,

as a site of ‘discipline’; and ‘joy’; the different proportions of ‘spirit’, ‘force’ and ‘wealth’, whose prudent handling

should avoid the disproportions of the armed avant-garde, the sect of theoreticians and the alternative enterprise

(p.238). Happiness is more or less the book’s last word, and, like all ethical truths which are not tied to forms-of-life,

this too cannot but taste somewhat thin or sound somewhat hollow, unless it is a screen on which to project the

spirit, force and wealth of our own localised struggles. The slippage to abstract morality, to a rhetoric that could

never really be spoken among friends, is not a problem for the Invisible Committee alone. It is our condition – acondition many of whose ideological pitfalls and fantasies are tracked down in this book with severity and insight.

That such a bracing discourse, and the untold acts that shadow and relay it, should need a foothold is perhaps

inevitable. That this foothold is a vitalism of sorts might not surprise. If confidence is not drawn from the

contradictions of structure, from the logic of your own domination, where else then than lived experience and

sensibility? The authors would do well to heed Franco Fortini's dialectical rejoinder to Adorno’s glum dictum: ‘No

true life but in the false’. Which also means no true life in and for itself, for, as Lukács had already observed in TheTheory of the Novel , the notion of life as it should be cancels out life.

Alberto Toscano <A.Toscano AT gold.ac.uk> is Reader in Critical Theory at Goldsmiths, University of

London. He is the author, with Jeff Kinkle, of Cartographies of the Absolute (Zero Books, 2015), and of

Fanaticism: On the Uses of an Idea (Verso, 2010). He edits The Italian List for Seagull Books and sits on the

editorial board of the journal Historical Materialism

7/24/2019 Alberto_Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/albertoburning-dwelling-thinking-mute 12/12

13/01/2015 20:58Burning Dwelling Thinking | Mute

Page 12 of 12http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/burning-dwelling-thinking#

0 Comments