Airbnb and the Rent Gap: Gentrification Through the ... · Airbnb and the Rent Gap: Gentrification...

Transcript of Airbnb and the Rent Gap: Gentrification Through the ... · Airbnb and the Rent Gap: Gentrification...

1

Airbnb and the Rent Gap: Gentrification Through the Sharing Economy

DRAFT; NOT FOR CITATION

David Wachsmuth and Alexander Weisler School of Urban Planning, McGill University

July 4, 2017

Abstract Airbnb and other short-term rental services are a topic of increasing interest and concern for urban researchers, policymakers and activists, because of the fear that short-term rentals are facilitating gentrification. This article presents a framework for analyzing the relationship between short-term rentals and gentrification, an exploratory case study of New York City, and an agenda for future research. We argue that Airbnb has introduced a new potential revenue flow in housing markets which is systematic but geographically uneven, creating a new form of rent gap in culturally desirable and internationally recognizable neighbourhoods which have generally already been subject to extensive gentrification. This rent gap can emerge quickly—in advance of any declining property income— and requires minimal new capital to be exploited by a range of different housing actors, from developers to landlords, tenants and homeowners. Performing spatial analysis on twelve months of Airbnb activity in the New York region, we measure the amount of rental housing lost to Airbnb, measure new capital flows into the short-term rental market, identify neighbourhoods whose housing markets have already been significantly impacted by short-term rentals at the cost of long-term rental housing, and identify neighbourhoods which are increasingly under threat of Airbnb-induced gentrification. Keywords: gentrification, Airbnb, short-term rentals, rent gap, urban political economy A referendum on innovation, or a referendum on gentrification? In early November 2015, residents of San Francisco voted on three measures concerning affordable housing in their increasingly pricey city. One would have raised $310 million for affordable housing, and a second called for a moratorium on development in the Mission neighbourhood. But most controversial was Proposition F—more commonly referred to as the “Airbnb initiative”—which became a battlefield in the growing war over the city’s housing. Backed by a coalition of housing activists, landlords, neighbourhood groups and hotel worker unions, Proposition F aimed to curb Airbnb and other short-term vacation rentals by limiting rentals to 75 days a year per unit (down from 90), strengthen enforcement and penalties, and provide compensation for neighbours who successfully sue violators. Proponents argued that Airbnb is intensifying gentrification in an already tight housing market by encouraging the conversion of affordable long-term rental units into short-term vacation rentals. Like other cities, San Francisco already has regulations in place, but they are widely considered ineffective; at the time of the vote, only about 700 of Airbnb “hosts” had complied with mandatory registration requirements, accounting for a small fraction of the city’s more than 9,000 listings.

2

The Proposition F coalition proved no match for Airbnb, which funneled $8 million into opposing the initiative. The centrepiece of the company’s efforts was a passive-aggressive ad campaign portraying San Francisco as a freeloader, with billboards saying things such as, “Dear Parking Enforcement, please use the $12 million in hotel taxes to feed all expired parking meters. Love, Airbnb.” (After public uproar, the company apologized for these ads, which also took credit for public libraries and public school art classes.) Airbnb mobilized like a political campaign. Spokesman Christopher Nulty called Prop F “an extreme, hotel-industry-backed measure,” downplaying affordable housing concerns (Weise 2015). They sent loyal users out to campaign door-to-door for them, sharing personal stories that portrayed Airbnb as an economic savour of the middle class. They invested in a television and mailer campaign, with ads warning residents that Prop F would incite neighbours to spy on and sue each other. They paid for over twenty-six hours of commercial time for the No side, compared to only sixteen minutes for the Yes campaign. With only $482,000 in funds—provided mostly by the hotel workers’ union—the Yes campaign was dwarfed financially. But Airbnb’s strongest numbers may not have been its coffers but its acolytes; with 138,000 users in a city of 450,000, the odds were stacked in its favour before a dollar was spent. In the end, Proposition F was defeated by a margin of 55% to 45%. But the debate over Airbnb and affordable housing has lingered over the Bay. The city maintained pressure on Airbnb through 2016, threatening steep fines for unregistered hosts and restrictions on multiple listings. And grassroots affordable housing advocates have answered Airbnb’s passive-aggressive billboards with their own outreach. In the summer of 2016, posters spotted in San Francisco’s Chinatown, addressed “Dear Airbnb Tourist”, implicated short-term rentals in the gentrification of the neighbourhood, ending with the wry note: “Have a nice visit in Chinatown” (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dueling messages in the San Francisco public sphere. (Credit: Airbnb, Marshall Kirkpatrick)

3

As the company’s home town, San Francisco has been a particularly notable site for the collision of Airbnb and gentrification, but cities and communities around the world are increasingly grappling with the impact of short-term rentals on their housing markets, and the question of whether and how to regulate the matter. Cities across North America and Europe have seen legislative showdowns fuelled by housing activism. Barcelona’s leftist mayor Ada Colau swept to office in 2015 with a platform that explicitly linked Airbnb with housing stress. Berlin has cracked down on short-term rentals in hopes of keeping housing affordable. Pricier capitals London and Amsterdam have limited rentals to 90 nights and 60 nights per year, respectively. And even while New York City and San Francisco dominate the US discourse, a range of mid-size cities across the country have challenged the company’s business practices. In the face of mounting pressure, Airbnb called détentes with several cities at the close of 2016, but activists remain vigilant in a rapidly shifting techno-political landscape. Yet, despite the enormous and growing policy and public interest in the impact of short-term rentals on housing affordability, there has so far been very little scholarly investigation of this problem, and even less from a critical-urban-studies perspective. In this article we address this deficit by presenting a framework for analyzing Airbnb and gentrification, an exploratory case study of New York City, and an agenda for future research. We argue that Airbnb has introduced a new potential investment flow into housing markets which is systematic but geographically uneven, creating a new form of rent gap in culturally desirable and internationally recognizable neighbourhoods which have generally already been subject to extensive gentrification. This rent gap can emerge quickly—in advance of any declining property income— and requires minimal new capital to be exploited by a range of different housing actors, from developers to landlords, tenants and homeowners. Performing spatial analysis on twelve months of Airbnb activity in the New York region, we measure the amount of rental housing lost to Airbnb, measure new capital flows into the short-term rental market, identify neighbourhoods whose housing markets have already been significantly impacted by short-term rentals at the cost of long-term rental housing, and identify neighbourhoods which are increasingly under threat of Airbnb-induced gentrification. Finally, we discuss the regulatory challenges which Airbnb has posed to local policymakers in New York, before concluding by offering a research agenda on gentrification and the sharing economy. Airbnb, the sharing economy, and housing affordability Airbnb is a short-term housing rental service, whose platform connects travelers with hosts. Its customers interact with the service much as they would interact with a hotel—making bookings for accommodation—but it is the hosts who list and charge for occupancy of their sofa, spare room, or entire unit, while Airbnb takes a commission of 9% to 15% per booking. The company launched in 2008 and enjoyed early successes during the Democratic National Convention in Denver, Colorado and the annual South by Southwest music festival in Austin, Texas that year. It now counts villas, castles, and luxury penthouses among its listings. At the close of 2016, the company boasted over two million listings around the world, and was valued at $30 billion—more than the Hilton and Marriot international hotel chains.

4

Alongside the ride sharing company Uber, Airbnb is one of the two leading lights of the so-called “sharing economy”, a contentious concept built on the peer-to-peer exchange of goods and services enabled by recent advances in information technology. The sharing economy has its free-market triumphalist advocates (e.g. Hopkins 2016), as well as progressive advocates who view it as an opportunity for destabilizing market-oriented consumerism and individual ownership (e.g. Sundararajan 2016). An emerging line of radical critique, meanwhile, conceptualizes it as a new kind of deregulatory right-wing populism (Morozov 2016; Slee 2016). At the heart of the controversy is the fact that the “sharing economy” doesn’t seem to involve very much sharing, in the sense of non-monetary exchange (Eckhardt and Bardhi 2015). Instead Airbnb and Uber have characteristically combined a kind of flexibility-cum-precarity for their users and operators with a major competitive push against, respectively, the well-entrenched hotel and taxi industries in cities across the world. While Uber’s drivers and Airbnb’s hosts are “liberated” from the need to obtain expensive taxi medallions or negotiate long-term rental leases, they are also “liberated” from union benefits, job security, and regulatory protections (Slee, 2014). Airbnb has effectively created a new category of rental housing—short-term rentals—which occupies a lacuna between traditional residential rental housing and hotel accommodation. Airbnb is by no means the sole provider of short-term rentals but it is by all accounts the dominant force; its closest competitor, Austin-based HomeAway, lists about half as many units worldwide. Nonetheless, Airbnb’s impact on cities and housing markets is not well understood, since the company takes great pains to cloud its operations from scrutiny. The New York Attorney General, for example, was forced to subpoena Airbnb’s data for the city, which the company eventually provided only in anonymized form. It was unclear how many transactions were excluded and the Attorney General’s office had to accept the anonymization in good faith. Airbnb’s business model has been particularly controversial because it so clearly flouts existing housing and land-use regulations in many or even most of the cities in which it operates, and does so in a fashion which appears to undermine policies aimed at protecting the supply of affordable housing. Airbnb and its advocates insist that these regulations must be updated to accommodate the new possibilities presented by the sharing economy. Opponents argue that Airbnb aims to avoid the regulation and taxation imposed on other businesses and threatens affordable housing in cities. The company’s practices have inspired a curious oppositional coalition of tenant associations, community groups, municipal governments, and hotels. Municipalities and affordable housing advocates share concerns about the effect of short-term rentals on the housing market, particularly in cities and neighbourhoods where demand is putting upward pressure on rents. Airbnb and related platforms have made it easier and more lucrative for landlords and property managers to offer units as year-round short-term rentals than long-term residential rentals. Accordingly, legislators and activists in cities from Boston to Berlin have begun to target short-term rentals as a housing affordability problem. “Cities are struggling to address urgent shortages of affordable housing and there is evidence that commercial interests in the [short-term rental] industry are removing residential units from housing markets and thereby contributing to even higher rents,” read a letter to the US Federal Trade Commission signed by urban lawmakers from

5

across the United States (Partnership for Working Families 2016). Several cities worldwide (most notably Berlin and Barcelona) have pursued near-total bans on the service, while 2016 saw a flurry of short-term rental legislation in cities across North America. In many municipalities, short-term rentals were already illegal according to pre-existing law, and new legislation has been used to increasing municipal monitoring and enforcement capacities. Several cities, such as Philadelphia and San Jose, have legalized short-term rentals but attempted to tax them, while others such as Phoenix have adopted an entirely laissez-faire posture. In general, municipalities recognize the huge amount of untaxed income enabled by Airbnb and argue that the service or users should pay their share. The New York Attorney General, for instance, estimates from subpoenaed data that the city should have received over $33 million in hotel room occupancy taxes alone from Airbnb between 2010 and 2014. Additionally, the anonymity provided by Airbnb means it is unlikely that hosts paid the necessary taxes at any level. Finally, municipal regulators have displayed reticence to confront small-time users—those who may occasionally rent out a spare room to supplement their incomes—instead focusing on so-called “commercial users”. Also known as “super users” or Airbnb’s full-time landlords, commercial users rent out multiple units on a full-time basis, and their share of the overall short-term rental market has been rising steadily, to approximately one third of overall Airbnb revenues in 2016 (Stulberg 2016). Community groups and housing advocates in cities across the world have begun to sound the alarm about the impact Airbnb is having on affordable housing in their communities, highlighting above all issues of racialized gentrification and displacement (see, e.g., BJH Advisors 2016; Lee 2016; Samaan 2015; New York Communities for Change 2015; Wiedetz 2017). In a 2015 white paper, the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy (LAANE) estimated that homesharing platforms took 11 units off the local rental market each day, accounting for a significant portion of new housing built since 2010 that was intended to slow rent increases. They found that professional landlords accounted for most of the profit of Airbnb and their competitors. From 2014 to 2015, the number of total listings skyrocketed while the presence of leasing companies increased from 6% to 9% of users, accounting for up to 37% of all revenue. Meanwhile, the share of hosts renting out a spare room decreased from 52% to just 36%, taking in only 16% of all income. LAANE argues that short-term rentals have offset municipal efforts to increase housing stock; in popular neighbourhoods, the number of full-time STR units is up to four times higher than the number of new units built since 2010. The study found that rents were rising much faster than average in popular Airbnb neighbourhoods, for which the platform has written travel guides on its website (Samaan 2015). A study by New York Communities for Change and Real Affordability for All found that Airbnb took approximately 20% of vacancies off the market in certain Manhattan and Brooklyn zip codes, and up to 28% in the East Village neighbourhood, even though it is technically illegal to rent an entire unit for less than 30 days. Overall, they estimated that the 20 neighbourhoods most popular on Airbnb have lost 10% of rental units (NYCC and RAFA 2015). These neighbourhoods are also featured in Airbnb’s neighbourhood guides. The company dismissed the report as “lies, fuzzy math and faulty stats” (Fermino 2015)—a curious inversion of the many critiques lodged against Airbnb’s own dubious claims of providing for the local economy.

6

Quality of life is also a concern for residents who have seen their neighbourhoods transformed into de facto hotel districts (Cócola Gant 2016). In the fall of 2016, residents of New Orleans, still recovering from Hurricane Katrina, held a jazz funeral at city hall (with coffins reading “RIP real neighbors” and “RIP affordable housing”) to mourn neighbourhoods lost to Airbnb tourism in a protest (Litten 2016). Meanwhile, hotel associations complain that short-term rentals effectively function as hotels but have an unfair advantage because they don’t pay taxes and don’t comply with safety and zoning regulations. Hotels also fear—plausibly, it turns out (Zervas et al. 2016)—that this grey-market enterprise will take away from their business. Amidst the growing scrutiny over Airbnb’s impact on affordable housing, in 2016 the company was thrust into the realm of racial politics in the United States, when a white paper found that Airbnb hosts are prone to reject African-American guests even if it means a loss in possible income (Edelman et al. 2017). This fuelled a flurry of media scrutiny, as well as a vague commitment to change from the company’s new “director of diversity” (Benner 2016b). In April, Airbnb (2016) released a report “Airbnb and Economic Opportunity in New York City’s Predominantly Black Neighborhoods”, which used testimony from families saving for college and African-American business owners to make the case that Airbnb helps middle-class African-American families make ends meet in New York. Their report boasted that usage had risen more than 50% faster in Black neighbourhoods than in the city as a whole. Of course, critics of the company were quick to point out that the most obvious interpretation of this fact is that Airbnb is helping to gentrify these neighbourhoods by taking affordable long-term rental units off the market. “Even in their release of the data in this study, [Airbnb] can’t help but admit all the illegal rentals that are posted on their website,” said New York City Council Member Helen Rosenthal, making the point that most of the 42% of listings that are full-unit rentals are likely in violation of state law (Garcia 2016). The short-term rent gap These debates and controversies in cities around the world provide significant circumstantial evidence that short-term rentals are implicated in gentrification. Accordingly, we now proceed to demonstrate that there is fire aplenty to go with this smoke. Our argument is that Airbnb and other facilitators of short-term rental housing are indeed systematically driving gentrification and displacement. Airbnb 1) simultaneously creates and provides a means for filling new technology-driven rent gaps, but it does so 2) in a geographically uneven fashion, concentrating in neighbourhoods with extralocal tourist appeal, which do not necessarily overlap with areas gentrifying due to more traditional state or market factors; 3) in a way which tends to crosscut existing interest groups in urban land markets—particularly landlords, residents, and municipalities. Because Airbnb is, first of all, a mechanism for producing new revenue flows through housing ownership, our theoretical point of entry is the rent gap. Neil Smith (1979) first proposed the rent gap model to offer a structural explanation for gentrification in American inner-city contexts such as New York City and Philadelphia. At its core, the rent gap model describes a situation where the actual economic returns to properties tend to decline or stagnate while potential

7

economic returns tend to increase. In neighbourhoods where this “gap” between actual and potential returns systematically increases, the result will be a correspondingly increasing incentive for real estate capital to direct new housing investment flows. As these investment flows drive up housing prices, attract more affluent newcomers, and displace existing poorer residents, the result is gentrification. Smith developed this model in a specific American urban setting loaded down with a host of specific cultural, social, and political-economic features, but the core of the rent gap model is relatively independent of these features. It simply states that where actual rents and potential rents diverge, a structural incentive for capital reinvestment begins to assert itself, and this incentive can be seen at work in cities around the world (Slater 2015; Lees et al. 2016). And as research on rural (Ghose 2004) and wilderness gentrification (Darling 2005) demonstrates, these conditions can well exist in even non-city spaces, with much the same result. Smith mainly discusses the case where this divergence occurs because of devalourization and neighbourhood decline—the common empirical picture of pre-gentrified neighbourhoods. But he also allows for rent gaps which emerge even in previously stable neighbourhoods, thanks to sudden shocks which drive up potential rents:

But it is also possible to conceive of a situation in which, rather than the capitalized ground rent being pushed down through devalorization, the potential ground rent is suddenly pushed higher, opening up a rent gap in a different manner. This might be the case, for example, when there is rapid and sustained inflation, or where strict regulation of a land market keeps potential ground rent low, but is then repealed. (Smith 1996: 68)

Indeed, Hackworth (2002: 828) (following Hammell 1999) has argued that rent gaps are increasingly likely to form through rising potential ground rent rather than decreases in actualized ground rent, “because the surrounding core of reinvestment has lifted the economic potential of all centrally located parcels”.1 The fact that short-term rentals have produced—effectively out of thin air—a new potential revenue stream in housing markets suggests the possibility that Airbnb is systematically creating rent gaps in cities around the world. This is our argument: across certain neighbourhood types (primarily still-gentrifying areas and now-affluent, formerly gentrifying areas), the new, technologically-enabled possibility of short-term rentals systematically raises potential ground rents—and thus creates rent gaps even where there has been little or no devalourization of existing housing. For dedicated entrepreneurs, monthly income from short-term rental properties can substantially exceed what could be realized through conventional long-term residential leases, particularly in cities with strong rent control regimes. And for “amateur” homeowners or tenants, the prospect of monetizing a spare room or staying with friends for an occasional weekend while their residence is rented similarly increases the overall rent achieved through the property. Airbnb is in effect shifting the “highest and best use” of residential housing in neighbourhoods with sufficient extra-local tourist interest, and the result is a rent gap.

1 Our thanks to Benjamin Theresa for drawing our attention to this point.

8

This argument builds in important respects on the concept of “transnational gentrification” proposed by Sigler and Wachsmuth (2016). Relying on a case study of the redevelopment of a historic neighbourhood in Panama City, they argue:

[In Panama City], localised disinvestment presents an opportunity for reinvestment capital not because of the neighbourhood’s changing relationship with metropolitan growth dynamics, but because of the neighbourhood’s changing relationship with a transnational middle class, for whom globalisation has rendered a physically distant locale increasingly accessible both logistically and imaginatively as a lifestyle destination. (Sigler and Wachsmuth 2016: 708)

Transnational gentrification occurs where rent gaps are globally scaled, and can create significant crisis for local residents who are forced to pay housing prices being set by global rather than local demand. Airbnb is an instance of this phenomenon; the service offers the opportunity for local capital to take advantage of extra-local demand. So what kind of rent gap does Airbnb produce? It is in part technological; the potential economic returns to the very same apartment may be higher now than it was a few years ago, for no other reason than the availability of a website which allows short-term visitors to stay there. At the small scale, leaving for the weekend didn’t formerly create a feasible opportunity for tenants to rent out their apartment. And at the large scale, even if there had been sufficient flows of tourism to keep an apartment continuously occupied with short-term visitors, what landlord could have handled the necessary logistics to find these tourists, collect payment, and manage the schedule? Airbnb’s technology platform creates new potential housing revenue flows because it solves these problems. Airbnb’s rent gap is also culturally mediated. Anyone can list their apartment on the service, but real economic activity only exists in areas where there is strong extra-local tourism demand. Some of these locations will be in pre-existing hotel districts and central business districts, but others will be in areas which do not have large hotel presences but nevertheless have cultural cachet—such as Williamsburg in New York, the Mission District in San Francisco, and inner East London. While Airbnb creates new technology- and culture-driven rent gaps by introducing the possibility of short-term rentals into formerly long-term housing units, it also offers the means of plugging those same gaps (see Figure 2). Contrast this with, for example, a major rezoning which raises potential ground rents in an area. The municipality takes the action which helps produce a rent gap, but other actors are necessary for realizing the higher rents—banks, developers, and the like. With Airbnb, the very same factor which creates the possibility of higher returns to housing also creates the means of achieving those returns. This decreases the turnaround time necessary to close the rent gap.

9

Figure 2. Variations of the rent gap: A) In Smith’s (1979) original analysis, a gap can open between gradually declining actual returns to property and the potential returns were the property to be redeveloped or put to the “highest and best use”, and when this rent gap becomes big enough, redevelopment and gentrification may follow. B) The minimal capital needed to take advantage of an Airbnb rent gap means that the gap can become large enough to motivate landowner action much sooner than with a traditional disinvestment-driven rent gap. C) Airbnb can cause potential income to rise sharply, creating a rent gap well in advance of any declining property income. Moreover, little or no new investment is necessary to capitalize on an Airbnb rent gap. Again, a comparison with received wisdom on gentrification is instructive here, since nearly every analysis of gentrification concerns cases where the “gap” itself needs to get large enough to justify the high cost of new construction or major renovations. Indeed, in Smith’s (1979: 545) original analysis of the rent gap, he explained that:

Gentrification occurs when the gap is wide enough that developers can purchase shells cheaply, can pay the builders’ costs and profit for rehabilitation, can pay interest on mortgage and construction loans, and can then sell the end product for a sale price that leaves a satisfactory return to the developer.

Not a single one of these steps is necessary for converting an existing residential unit to a short-term rental. While serious Airbnb entrepreneurs may well refurbish their units to increase their success with the service (Kalinowski 2016), the only necessary step for converting a long-term rental to a short-term rental is to remove the existing tenant. This has three immediate implications. The first is that relatively small rent gaps can motivate conversion to short-term rentals; no new mortgages need to be taken out, or contractors hired. The second is that owners of rental units in areas where there is strong tourist demand for short-term rentals face strong economic incentives to evict existing tenants, or to not find new tenants when previous ones depart, in order to quickly and cheaply realize the higher possible rents. The third is that the growth in short-term rentals is very likely to be coming at the expense of long-term rental housing, as the latter gets converted to the former to take advantage of new rent gaps. Either in the short-term with actual evictions, or over a slightly longer timescale as long-term rental housing is “organically” converted to short-term rental, the result will be displacement. Slater (2015: 12) remarks that “a challenge for students of rent gap theory is…to illustrate specifically how the opening and closing of rent gaps leads to the agony of people losing their homes.” In the case of home-sharing services, this mechanism is unfortunately straightforward.

10

By creating higher potential returns to property through the possibility of short-term rentals, Airbnb produces rent gaps, and thereby should be expected to drive gentrification and displacement. But the “opportunity” Airbnb offers to landlords and tenants is highly uneven, because it directly depends on the magnitude of tourist demand for short-term accommodation. Accordingly, we should not expect Airbnb’s rent gaps, and the resulting gentrification and displacement, to be equitably distributed across urban space. As a first approximation, Airbnb demand is likely to be particularly concentrated in the following two neighbourhood types: 1) areas near the central business district which have historically featured high rates of hotels, hostels, B&Bs and other forms of short-term tourist accommodation—i.e. areas with strong pre-existing tourist demand; and 2) residential areas with strong cultural cachet, good public transit, and leisure amenities—i.e. gentrifying or recently gentrified areas, which haven’t historically hosted tourists in large numbers. Conversely, Airbnb demand is likely to be weak in poor and racialized neighbourhoods lacking (white, middle-class) tourist-friendly cultural amenities, as well as more suburban areas with poorer public transit connectivity to the central city. From a gentrification-theoretical perspective, therefore, we should expect Airbnb-induced gentrification pressures to overlap incompletely with other drivers of gentrification. Short-term rentals may exacerbate housing pressures in already wealthy areas experiencing so-called “super-gentrification” (Lees 2003) as well as in areas undergoing more traditional 2nd- or 3rd-wave (Hackworth and Smith 2001) gentrification processes, particularly in their more advanced stages. Meanwhile, in poor neighbourhoods which are experiencing gentrification pressures but which are not (yet) understood as desirable destinations for extra-local visitors, short-term rentals may not be a significant exacerbator of these pressures. In addition to its geographical unevenness, there is a second dimension of unevenness to Airbnb-driven gentrification—the extent to which it creates incentives to action which crosscut existing urban interest groups. To begin with, we can note that the rent gaps which Airbnb and other short-term rental services produce can be plugged in different ways by different actors in the housing market. Tenants can tap into new potential housing revenue streams by renting out a spare room, or staying at a partner’s house on the weekends. Behaviour of this sort intensifies the use of scarce housing resources, redistributes revenue within the short-term accommodation sector (to Airbnb-using tenants from hotels, which would have received a booking had Airbnb not been an option), and also probably shifts the net revenue entering this sector (because some people spend less money on Airbnb than they would have for a hotel room, and others choose to rent an Airbnb apartment instead of staying with friends or family), but it doesn’t otherwise imply any significant shifts in the political economy of urban housing markets. At the same time, landlords (and sometimes tenants) can use Airbnb in a superficially similar way which nevertheless has very different effects: converting existing long-term residential units into full-time short-term rentals. Similarly, a small-time investor can buy a condominium (which would otherwise be expected to serve as stable long-term housing) and contract with one of the proliferating Airbnb management firms which will oversee the unit in exchange for a share of the proceeds. Behaviour of this sort does not simply redistribute revenue within the short-term accommodation sector. It de-intensifies housing use (by replacing constant long-term tenants

11

with sporadic short-term ones, drives down the supply of long-term residential housing in specific neighbourhoods, and therefore plausibly drives vacancy rates down and market rents up. Short-term rentals generate political-economic interests which cut across important existing housing-market positionalities. Some tenants will support Airbnb because they can rent out their apartment for a little extra income, while other tenants will oppose it because neighbours’ use of it effectively turns their apartment building into a hotel. Some landlords will support Airbnb because they can make more money renting their unit short-term to tourists than they would with traditional long-term residential leases (and because they can avoid having their economic power curtailed by tenants exercising their rights), while other landlords will oppose it because their Airbnb-using tenants are causing hassles for their buildings. Some municipalities or sub-municipal jurisdictions will support Airbnb to encourage tourism-based local economic development, while others will oppose it out of deference to a strong hotel lobby. And these examples only consider the supply-side; any of these actors will have different interests in their demand-side capacity as tourists and users of short-term accommodations. The result is that, while in theory Airbnb and other short-term rental operators should be vulnerable to municipal regulatory action, in practice the issue of short-term rentals generates fragmented political coalitions which makes such action more difficult for motivated regulatory agents to carry out. Is Airbnb gentrifying New York? To substantiate this theoretical argument, we now turn to a case study of Airbnb’s activities in New York City over the last several years. We measure and describe Airbnb’s impact on housing markets throughout the city, and document the emergence of new Airbnb-driven rent gaps in specific neighbourhoods. We contextualize this information by discussing ongoing political conflicts over whether and how Airbnb should be regulated in New York. Findings in this section rely on the following sources: Data on Airbnb listings, which includes canonical information about listing type (private room or whole house), asking prices, and other per-listing variables, along with per-listing revenue estimates, was obtained from the consulting firm Airdna. This data was correlated at the census tract level with 2015 American Community Survey data (five-year estimates) concerning housing and demographic characteristics.2 To supplement this data we consulted a wide variety of policy and media reports, and conducted six information-finding interviews with community organizers and government officials in the New York region. Airbnb’s impact on housing in New York Airbnb’s relationship with governments and civil society groups in New York has been contentious for nearly the company’s entire history. To some extent this is because Airbnb is simply the newest iteration of a long-standing housing regulatory challenge in New York: short-term rentals and illegal hotel conversions. In fact, rentals of less than 30 days in residential 2 Full methodological details are available in an online appendix at www.davidwachsmuth.com/airbnb/.

12

apartment buildings have been illegal since the 1929 passage of New York State’s Multiple Dwelling Law. Despite this law, in the early 2000s legislators and community organizations in Manhattan began to receive increasing numbers of complaints about apartment buildings being converted to short-term rentals. Complaints were most common on the West Side, which already hosted the city’s largest concentration of single-room-occupancy (SRO) housing. Residents had begun to notice tourists or frequent visitors to neighbouring units, and registered complaints about safety and quality of life, as well as fears of being evicted as their buildings transformed into de-facto hotels. In response, a group of legislators and civil society actors formed an Illegal Hotel Working Group in 2005, when short-term rentals were still mostly facilitated by individual operators. A report from the group identified hundreds of illegal hotel conversions and documented the impacts of these conversions both on individual tenants (harassment, security concerns and loss of quality of life) and on the city as a whole (loss of housing supply and municipal revenue, and damage to legitimate hotels) (Illegal Hotel Working Group 2008). In retrospect, these illegal hotels were a precursor to the “sharing economy” version of short-term rentals, of which Airbnb is now by far the dominant player. One of the members of the Illegal Hotel Working Group—the executive director of a housing organization on the West Side of Manhattan—describes the transformation in short-term rentals which their organization witnessed since the mid-2000s:

We saw the growth that went from being just predominantly Midtown Manhattan, or controlled through individual operators, to being this large marketplace where anyone could post. All of a sudden we started to see what we had been seeing on a local level—on the West Side—replicated across the city…. We were seeing apartments that had been available for permanent rentals were now being exclusively used for short term rentals. We had taken steps legislatively to try to conquer that over the ten years, but all of a sudden, with the advent of…Airbnb, it just exploded.

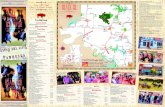

Indeed, the scale of Airbnb’s activities renders earlier concerns in New York about illegal hotels almost quaint by comparison. While in the mid-2000s the Illegal Hotel Working Group (2008) identified 224 illegal hotel conversions in New York City, over the one-year period from October 2015 to September 2016, there were approximately 110,000 active Airbnb listings across the New York region, of which more than 80% were in New York City itself.3 New York City is Airbnb’s largest market, generating nearly $700 million in host revenue over the year. Figure 3 shows the total distribution of active listings across the entire region in this period, along with the percentage of total housing units these listings accounted for in the area of highest concentration. It reveals hotspots in Hell’s Kitchen and Chelsea (near the existing Manhattan hotel district, an area with a long history of illegal hotels), the Lower East Side, and Williamsburg and Bushwick in Brooklyn.

3 This one-year period (October 2015 to September 2016) is used for all subsequent analysis, and is referred to as “2016” for the sake of simplicity.

13

Figure 3. Active 2016 Airbnb listings in the New York region. The unevenness of Airbnb’s presence in New York means that any city- or region-wide aggregate statistics are going to be highly misleading—and indeed these are the statistics the company leans on in its public relations (e.g. Airbnb 2015; see also Cox and Slee 2015). All the 110,000 listings shown in Figure 3 were active during the study period, but many were just rented once or twice, or even not at all. Meanwhile, 14 (four in each of Brooklyn and Queens, and six in Manhattan) were rented for 360 or more days of the year, generating an average of $42,500 each in annual revenue for their hosts. As discussed above, the political and policy implications of occasional Airbnb rentals and full-time rentals are distinct, since the former represent an intensification and the latter a de-intensification of overall housing use. The last several years have witnessed an increasing concern among community organizations and housing observers in New York about the loss of long-term rental housing to short-term rentals. For example, the director of a housing-focused non-profit described their recent experience with Airbnb on the Manhattan West Side:

[We started to] realize that short term rentals were so lucrative that…landlords were renting them out in place of renting to tenants, and that it was starting to impact the housing that was available. It also provided an incentive to evict people. If you were getting $1000 month rent from this tenant who had been there a while, and if you kick them out you could charge $200 a night, there’s definitely an interest in getting that person out.

The data bear out this concern on a city-wide scale. There were 13,000 whole-unit listings rented more than 60 days and available more than 120 days in 2016.4 If we compare this number with 4 While in theory a “full-time” Airbnb rental is one for which there is no primary occupant (tenant or owner) living in the unit year-round, in practice it is impossible to verify this status unit by unit. Instead, attempts to estimate Airbnb’s impact on housing markets generally choose an occupancy threshold beyond which a unit is considered unlikely to be occupied by a long-term resident. Inside Airbnb (2017), for instance, defines “frequently rented” units

Coordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 18N¯ 0 25 50 km

All Airbnb listings

1 Dot = 10

New York City

New York MSA

All Airbnb listings as apercentage of totalhousing units

0% - 2%

2.1% - 6%

6.1% - 12%

12.1% - 24%

24.1% - 45.5%¯ 0 2.5 5 kmCoordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 18N

14

the amount of normal rental units in the region, we can estimate what portion of each neighbourhood’s rental housing stock has been lost to Airbnb (Figure 4). The numbers are shocking; many census tracts appear to have seen three percent or more of their long-term rental housing converted into Airbnb hotels. (A further 9,200 private rooms were rented 60 days or more and available 120 or more, and many of these will have displaced long-term renters as well, but we have excluded these from the analysis to err on the conservative side.) There is no way to estimate how many tenants were forcibly evicted or harassed out of their apartments to free up units for Airbnb, and how many units were simply converted to short-term rentals after they “naturally” became vacant. But in either case, the result has been a massive and concentrated loss of rental housing in the city. To put the numbers in perspective, the city-wide rental vacancy rate was 2.7% in 2015 (US Department of Housing and Urban Development 2016). In the subsequent year, a roughly equivalent percentage of rental housing in Lower Manhattan and Williamsburg appears to have been converted into full-time Airbnb use.

Figure 4. The 2016 percentage of rental housing units occupied on Airbnb more than 60 days and available more than 120 days a year, and hence likely to have been removed from the long-term rental market, at the census-tract and sub-borough scales. Airbnb’s two rent gaps: filled and unfilled Airbnb’s impact on New York’s housing supply can be summarized by the approximately 13,000 housing units in the city which we argue have shifted from the long-term rental market to short- as those rented on Airbnb for 60 or more days per year, arguing that “Entire homes or apartments highly available and rented frequently year-round to tourists, probably don’t have the owner present, are illegal, and more importantly, are displacing New Yorkers”. We have used the same occupancy threshold while also setting a threshold of 120 days of annual availability, to filter out highly efficient part-time listings which are, for example, only listed each weekend but are successfully rented most of that time. The 13,000 listings which meet the 60/120 threshold are available on average 256 nights a year, and rented on average 148 nights a year.

Full-time, whole-unitAirbnb listings as apercentage of rentalunits

0% - 0.8%

0.9% - 1.5%

1.6% - 3%

3.1% - 6%

6.1% - 11.6%¯ 0 2.5 5 kmCoordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 18N

214

248

912

262

501

463

299

325

1656

479

358

1134

643

151

245

680

263

370

1299

¯ 0 2.5 5 km

Full-time, whole-unitAirbnb listings as apercentage of rentalunits

0% - 0.4%

0.5% - 0.8%

0.9% - 1.2%

1.3% - 1.6%

1.7% - 2.5%

# of listingsCoordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 18N

1636

15

term Airbnb rentals—highly concentrated in Lower Manhattan and North Brooklyn. But to more directly answer the question of Airbnb’s relationship to gentrification and the rent gap in New York, we need different metrics. The rent gap is fundamentally about real estate capital—revenue flows through the urban housing market. The existence of a rent gap means that, systematically across a neighbourhood, landowners could earn more money from some different use of their property than from the existing use, which creates an incentive to reinvestment and hence gentrification. Numerous observers of New York’s housing market who have seen Airbnb’s impact up close argue that the company has provided precisely this incentive to landlords across the city. For example, here is an attorney who works on housing issues in New York:

This entire issue is about the commodification of housing, the commercialization of housing. You see people who’ve been living in their communities for decades and the next thing you know, in addition to all of the other pressures that we see in New York City in the housing market, you have yet another incentive for owners and third parties to step up the harassment tactics and the displacement pressures to free up these units for even more profits.

Likewise, the housing non-profit director quoted above argued that hosting short-term tenants can not only earn landlords more money, but also allow the latter to avoid having their money-making capacity constricted by tenant rights:

[Airbnb] joins a long list of incentives to evict long-term tenants in New York. I’ve no doubts that was certainly a motivator by just being able to earn more money per unit. And frankly having a short-term tenant can be a whole lot easier than having a long-term tenant, who may sue you for not having keys, you may have to bring to court if they don’t pay their rent, or violate their lease in some way. A short-term tenant doesn’t have those same rights, and can be a lot easier to maintain as well.

While gentrification researchers generally expect rent gaps to be filled through new capital investment—renovations and redevelopments—in the case of Airbnb this often won’t be necessary. Property owners can simply supply furniture and switch their units from residential leases to short-term rentals. If there has been an Airbnb-induced rent gap, we shouldn’t expect to see big new capital expenditures; instead we should expect to see routine rental housing revenue flows diverted into Airbnb. The first map in Figure 5 shows Airbnb’s share of all rent payments across a 12-month period, and thereby provides an estimate of where Airbnb has created and already plugged a rent gap. The basic pattern is similar to the previous maps, although the clustering is even more acute. Airbnb as a new revenue stream from housing has been most consequential in Times Square, the Lower East Side, and Williamsburg. These are the areas where Airbnb created a rent gap, and where landlords have shifted housing supply into short-term rentals to capitalize on that rent gap. Importantly, these three neighbourhoods are all “post-gentrified”, in the sense that they saw massive increases in rents and massive displacement over the last several decades, and now have been to a greater or lesser extent transformed into wealthy neighbourhoods. Airbnb has had its biggest impact to date, in other words, not at the gentrification “frontier” (Smith 1996), but in areas that have already been pervasively restructured by capital. It is further intensifying gentrification and displacement dynamics where these dynamics have already been acute.

16

Figure 5. Two Airbnb rent gaps in New York: the rent gap which has already been filled, shown by the percentage of rent payments which now flow through Airbnb; and the rent gap which is still open, shown by the profitability of an average Airbnb listing compared to median 12-month rents in the neighbourhood. However, a different picture of Airbnb’s impact emerges through examining how much landlords can earn on the service relative to prevailing rents in their neighbourhoods. Leaving aside the previous question of where total Airbnb revenue flows have been highest, where are individual landlords making the most money on Airbnb relative to what they could have been making with traditional long-term rentals? The second map in Figure 5 answers this question, and reveals a completely different geography from the previous maps. While the Lower East Side remains a hotspot on this map, with average full-time Airbnb revenues in the range of 200-300% of median rents, the other major areas of Airbnb activity—Williamsburg and Hell’s Kitchen—have significantly receded in importance. Meanwhile, three new neighbourhoods have appeared: Harlem in North Manhattan, Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, and Union City and its surrounding areas in New Jersey. These are areas where there isn’t yet a lot of Airbnb activity in absolute or even relative terms, but where the landlords who are using Airbnb are making a lot more money than they would have in the long-term rental market. Put differently, the second map in Figure 5 shows the neighbourhoods which appear to have large and unfilled rent gaps—where there is money to be made but where landlords haven’t yet seized on the opportunity en masse. These are the neighbourhoods at greatest risk for Airbnb-induced gentrification in the near future. And whereas current Airbnb impacts were concentrated in already-gentrified areas, these at-risk neighbourhoods are all still very clearly at the gentrification frontier. Comparing these two patterns—the percentage of housing revenue that now flows through Airbnb, and the percentage of the median rent which an average full-time Airbnb property earns—allows us to see where Airbnb has already had a major impact on local housing and where it is likely to have an impact in the future. The first pattern indicates where Airbnb has already had a major impact on local housing—where it has created and filled a rent

Airbnb revenue as apercentage of totalrental revenue

0% - 1%

1.1% - 2%

2.1% - 3%

3.1% - 4%

4.1% - 7%¯ 0 2.5 5 kmCoordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 18N

Percentage of medianrent earned by averagefull-time, whole-unitAirbnb listing

22% - 150%

151% - 200%

201% - 250%

251% - 300%

301% - 1118%¯ 0 2.5 5 kmCoordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 18N

17

gap. The second pattern indicates where there is still money to be made for landlords by converting long-term rental housing to short-term rentals—where Airbnb has created a rent gap which hasn’t yet been filled. These two patterns are synthesized in the first map of Figure 6, which presents a vulnerability index for Airbnb-induced gentrification in New York. First, shown in blue, are the areas which have had their housing supply heavily impacted by Airbnb, but which may be close to reaching an equilibrium (a closed rent gap).5 Most of lower Manhattan and Williamsburg fit this profile. Second, shown in red, are the areas which haven’t yet been seriously impacted by Airbnb, but are in real danger of it in the near future, because of how much more money landlords in these areas are making by using Airbnb (an open rent gap).6 Harlem in Manhattan and Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn fit this profile. Last, shown in purple, are the areas which have already been heavily impacted by Airbnb, but where there appears to be more impact still to come (a not-yet closed rent gap). The Lower East Side and parts of Brooklyn fit this profile.

Figure 6. An Airbnb-gentrification vulnerability index, and its juxtaposition with race, indicating that the likely next frontiers of Airbnb-induced gentrification in New York are racialized (and particularly African-American) neighbourhoods. The second map of Figure 6 demonstrates the strong overlap between the patterns of Airbnb-induced gentrification and racial segregation. In short, Airbnb has had its greatest impact so far in largely non-Hispanic white neighbourhoods, while the areas it is increasingly threatening are largely African American and Hispanic neighbourhoods. Areas suffering high current impact of Airbnb in New York are only 35% non-white, while areas at high risk of future impact are on 5 These are the census tracts whose Airbnb revenue as a proportion of total rental revenue was more than two standard deviations higher than the regional mean. 6 These are the census tracts belonging to statistically significant clusters of high profitability of an average Airbnb listing compared to median 12-month rents in the tract. Cluster analysis (using an Anselin local Moran’s i) was used to mitigate the noisiness of the underlying pattern.

Non-white population

0% - 20%

21% - 40%

41% - 60%

61% - 80%

81% - 100%

Airbnb-gentrificationvulnerability index

High current

impact

High risk of

future impact

High current

impact and risk¯ 0 2.5 5 km

Coordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 18N

Airbnb-gentrificationvulnerability index

High current

impact

High risk of

future impact

High current

impact and risk¯ 0 2.5 5 km

Coordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 18N

18

average 65% non-white. (The entire New York region is 52% non-white.) Given emerging research demonstrating the prevalence of racial discrimination on Airbnb (Cox 2017; Edelman et al. 2017), the pattern identified here implies the impending arrival of a new intensification of racialized gentrification in New York. Regulating Airbnb in New York Municipal and state agencies in New York attempting to regulate Airbnb’s activities have had to confront four overlapping challenges: ambiguity over the applicability of existing laws to the new business of online short-term rentals, the difficulty of inspection-based enforcement operations, the lack of reliable data about Airbnb, and the company’s protection under the federal Communications Decency Act. The cumulative result of these challenges has been an uncertain and conflictual regulatory arrangement. In 2010, New York State lawmakers amended the longstanding Multiple Dwelling Law, which had previously prohibited sublets or rentals of less than 30 days in residential apartment buildings. The amended law now required that a permanent resident must be present during such a rental period, effectively precluding the short-term rental of an entire unit, and, by requiring hosts to live alongside their guests, in theory better preserving quality of life in the building. Additionally, anyone who rents out a unit on a short-term basis became required to pay applicable taxes. Although Airbnb had been founded several years earlier, in 2008, its use wasn’t widespread enough yet to have become a target of legislation; the Multiple Dwelling Law amendment was aimed instead at illegal hotels and boarding houses. Nevertheless, within a few years, when Airbnb had become an enormous player in the tourism accommodation business in New York, opponents of the company became increasingly vocal about the fact that the Multiple Dwelling Law also appeared to render nearly all whole-home Airbnb listings in the city illegal. According to a staff member in a State Senate office in Manhattan, municipal efforts to regulate Airbnb in this timeframe were held back by uncertainty about the applicability of the Multiple Dwelling Law and other State and local laws: “The city couldn’t act until they had clear laws and definitions.” Two major challenges have been conflicting definitions regarding primary residency, and ambiguity about whether landlords or tenants should be held responsible for tenant violations. (The latter issue resulted in landlords filing lawsuits against the City when they were charged for their tenants’ actions.) Since 2015, New York City’s enforcement efforts have been led by a de facto Airbnb police force operating out of the Mayor’s Office of Special Enforcement, a quality-of-life-focused unit which includes building inspectors, fire inspectors, police, the sheriff’s department, financial investigators, and city attorneys. An official at the Office described their enforcement procedure as fundamentally driven by resident complaints and in-person inspections:

Searching for listings on Airbnb is not productive, since information is obscured to virtual unusability, but once someone is on the radar as a commercial user we can pursue them through listings…. Complaints are key. They are real—not just listings. [Those who file complaints] can also act as witnesses and tell us when the best time to catch offenders is.

19

Importantly, the Office gives violations to building owners, or landlords, rather than offending tenants, with the understanding that landlords can mete out their own justice under lease agreements. Outside observers have been skeptical about the City’s inspection-driven enforcement approach, however; here, for example, is a Manhattan housing non-profit director:

Enforcement is so problematic. Let’s say you said you could rent it out 30 days in a given year; in order to actually determine that someone is not complying, you have to send an inspector on 31 separate days to verify that.... It’s just unenforceable. The ability to profit from it is too great.

As we have already demonstrated, Airbnb activity in the New York region is heavily concentrated in the New York City boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn. It is therefore worth noting that administrators and politicians in the two boroughs have generally taken quite different positions on Airbnb. Brooklyn Borough Hall has actually partnered with Airbnb to promote tourism, at the same time as their counterparts across the river have led the regulatory charge against the company. The Borough President’s office argues that city- and state-wide regulations and legislation are based on Manhattan’s context and clumsily applied to Brooklyn. Brooklyn does not have the Manhattan’s history of SROs and illegal hotel conversions, but, above all, Brooklyn does not have an existing tourism hospitality sector which is threatened by Airbnb. Tourists to New York have traditionally stayed in Manhattan, and Brooklyn Borough Hall sees short-term rentals as a small business opportunity that can help residents make ends meet and bring increased foot traffic to outlying neighbourhoods. According to one Borough Hall staffer, while redevelopment has pushed east, tourism-related economic benefits are not spread the same way: “Rents are going up, residents are well off, but tourists aren’t spending there.” Leaving aside the odd juxtaposition of “rents are going up” and “residents are well off”, the fact that Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighbourhood is one of the three New York neighbourhoods currently undergoing intense gentrification-related pressure from Airbnb implies that tourists will soon be spending there as well. The first near-decade of Airbnb’s operations was characterized by extreme intransigence in the face of requests—and eventually demands—for cooperation with municipal authorities. One manifestation of this has been data; Airbnb is notoriously possessive of their data, the lack of which prevents New York and other municipalities from making informed decisions about short-term rentals in their jurisdictions. In 2014 New York State’s Attorney General subpoenaed Airbnb’s records on hosts operating in the state, and the company initially refused to comply. After winning a judicial victory which narrowed the scope of the subpoena, the company eventually handed over the required information. A year later, Airbnb voluntarily shared a one-day snapshot of data from New York City with lawmakers, but independent analysts demonstrated that the company had carried out an unprecedented purge of listings just days beforehand, raising persuasive doubts about the data’s representativeness and accuracy (Cox and Slee 2016). Under the federal Communications Decency Act of 1996, platforms that don’t control content can’t be targeted for that content, and Airbnb has used this act as a shield to protect itself from regulation and oversight. Most importantly, Airbnb has been able to resist legislative attempts to force it to proactively police the listings on its site to conform to local laws. According to a New York housing attorney who has helped lead advocacy efforts to regulate Airbnb:

20

[Airbnb] refuses to, in a very transparent and responsible way, sit down and be a true partner here in New York City. Instead they just come here and they impose their business model on us and our laws as they do everywhere else around the world.

Constrained by the Communications Decency Act from requiring Airbnb to remove illegal rentals from its site, State legislators have instead recently introduced legislation to stop users from advertising illegal apartments. In late 2016, Governor Cuomo signed a bill into law which made it illegal to advertise a rental of less than thirty days. If effective, this law locates the offense at solicitation, instead of requiring the Mayor’s Office to investigate whether a transaction has occurred. This law also identifies the host themselves, who posts the ad, as the culprit rather than the building owner. Immediately after the law’s passage in October 2016, Airbnb challenged it in court. But, two months later, in what was seen as a shocking about-face, the company dropped the lawsuit under the condition that hosts—rather than Airbnb itself—face the up-to-$7,500 fines (Benner 2016a). This capitulation capped a month in which Airbnb decided to call truces with some of the city governments which had been most hostile to it, agreeing to cooperate with regulatory efforts in the US and Europe. The company’s retreat started in its hometown of San Francisco, when a federal judge dismissed their request for an injunction against new legislation that vowed to fine Airbnb $1,000 per day per illegal listing in the city (Said 2016). For the first time Airbnb agreed to directly police its hosts by limiting listings to one per host and eventually blocking the rental of a unit for more than 90 days; the company also promised to release user information to authorities. (In its compromise with New York State, Airbnb didn’t agree to any such demands.) Soon after, the company pledged to deals with London and Amsterdam, in which they would take on responsibility for limiting unit rentals to 90 days a year in London and 60 in Amsterdam (Woolf 2016). Conclusions: A research agenda for gentrification and short-term rentals The purpose of this paper has been to analyze the intersection of gentrification and short-term rentals. Using a case study of New York City, we have argued that Airbnb has introduced a new potential investment flow into housing markets which is systematic but geographically uneven, creating a new form of rent gap in culturally desirable and internationally recognizable neighbourhoods which have generally already been subject to extensive gentrification. This rent gap can emerge quickly—in advance of any declining property income— and requires minimal new capital to be exploited by a range of different housing actors, from developers to landlords, tenants and homeowners. We now conclude by offering several themes for future research on gentrification and short-term rentals, in the hope of developing a more consistent body of knowledge to inform scholars, policymakers and activists. The first theme is uneven development. As our examination of New York has demonstrated, short-term rental activity is distributed in a highly uneven fashion across the urban landscape. In New York the clusters were most pronounced in the city’s traditional tourism area and in several neighbourhoods which have not historically been major tourism draws but do have internationally recognizable cultural cachet. Does this pattern exist in other cities? Furthermore, the neighbourhoods with the most Airbnb activity are not necessarily the

21

neighbourhoods where the impact on existing rental housing is strongest—a situation we captured in New York with the vulnerability index (Figure 6, above). Understanding geographically-specific vulnerability patterns in other cities is thus an urgent research task. A related theme is displacement; just as the impact of short-term rentals on neighbourhoods is geographically uneven, it is also almost certainly socially uneven. Short-term rentals are removing rental housing from the market, but are conversions from standard rental apartments to de facto Airbnb hotels more or less likely to displace existing residents than more traditional forms of gentrification-related urban redevelopment? Our quantitative empirical analysis of New York was unable to measure displacement directly, and without observation and qualitative research, future research will be likewise limited to making neighbourhood-scale inferences about likely displacement. Yet displacement is, ultimately, the key moral stakes of gentrification (Slater 2009), and understanding the extent to which short-term rentals are displacing people from their homes is a correspondingly vital topic for future research. A third issue is regulation and regulatory conflict. Cities around the world are currently scrambling to develop regulations on short-term rentals, but we still have very little understanding about which attempts at regulation have proven effective so far, and which have proven political feasible. Relatedly, as our discussion of Airbnb regulation in New York has demonstrated, regulators do not always speak with one voice, or even share basic interests with respect to the so-called sharing economy. Researchers thus need to be understand the political economy of short-term rentals better: what leads different state and civil society actors to take different positions on how short-term rentals should be regulated, and what leads them to invest significant resources into securing their desired outcomes? The final theme for future research is data availability. Research into the impact of short-term rentals on urban housing and land markets is hampered at present by the lack of first-party data from Airbnb and other home sharing platforms. Airbnb has been clear that they see protection of their data as a strategic decision, so it is unlikely that they will voluntarily release it in any but the most opportunistic public-relations fashion, as with their highly misleading 2015 New York data release (Cox and Slee 2016). At present there are three independent sources of data on Airbnb’s activities, all of which are derived from automated scraping of the public Airbnb website at certain intervals. An important task facing researchers of short-term housing is systematically to compare these three data sources to understand their separate strengths and weaknesses, and whether they can be combined to generate higher confidence estimates of Airbnb’s activities. The explosive growth of Airbnb—from a few hundred thousand nights booked in 2010 to 25 million in 2015 and 50 million in 2016—makes clear the urgent need for better understanding the impact of short-term rentals on urban housing markets and the regulatory options available for controlling them. At their core, short-term rentals are facilitating a massive and perhaps unprecedented intensification of the commodification of housing. Airbnb and other “sharing economy” corporations are transforming our cities, while communities (aided in many cases by civil society and state actors) are resisting that transformation and articulating other visions for “sharing” in the city. Critical urban researchers should seize the opportunity to contribute to these visions.

22

Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank David Chaney, Danielle Kerrigan, and Andrea Shilolo for their research assistance, and Ahmed El-Geneidy, Emily Grise, Brian McCabe, Adrian Phillips, and Benjamin Theresa for their help and feedback with earlier drafts of this paper. References Airbnb. 2016. Airbnb and Economic Opportunity in New York City’s Predominantly Black

Neighborhoods. Policy report. ------. 2015. Economic Impact Report: New York City. Available online at <https://new-york-

city.airbnbcitizen.com/economic-impact-reports/data-on-the-airbnb-community-in-nyc/>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Benner, Katie. 2016a. Airbnb Ends Fight with New York City over Fines. New York Times. Available online at <http://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/03/technology/airbnb-ends-fight-with-new-york-city-over-fines.html>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

------. 2016b. Airbnb Hires First Director of Diversity. New York Times. Available online at <http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/05/technology/airbnb-hires-first-director-of-diversity.html>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

BJH Advisors. 2016. Short Changing New York City: The Impact of Airbnb on New York City’s Housing Market. Policy report prepared for Housing Conservation Coordinators and MFY Legal Services.

Cócola Gant, Agustín. 2016. Holiday Rentals: The New Gentrification Battlefront. Sociological Research Online 21 (3): 10.

Cox, Murray. 2017. The Face of Airbnb, New York City: Airbnb as a Racial Gentrification Tool. Inside Airbnb. Available online at < http://insideairbnb.com/face-of-airbnb-nyc/>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Cox, Murray and Slee, Tom. 2016. How Airbnb’s data hid the facts in New York City. Policy report. Available online at <http://insideairbnb.com/reports/how-airbnbs-data-hid-the-facts-in-new-york-city.pdf>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Darling, Eliza. 2005. The City in the Country: Wilderness Gentrification and the Rent Gap. Environment and Planning A 37 (6): 1015-1032.

Eckhardt, Giana M. and Bardhi, Fleura. 2015. The Sharing Economy Isn’t About Sharing at All. Harvard Business Review. Available online at < https://hbr.org/2015/01/the-sharing-economy-isnt-about-sharing-at-all>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Edelman, Benjamin, Luca, Michael, and Svirsky, Dan. 2017. Racial Discrimination in the Sharing Economy: Evidence from a Field Experiment.

Fermino, Jennifer. 2015. Airbnb Taking up 1 out of 5 Vacant Apartments in Popular New York City Zip Codes: Study. New York Daily News. Available online at

23

<http://www.nydailynews.com/news/politics/airbnb-takes-1-5-apartments-popular-nyc-zip-codes-article-1.2307521>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Garcia, Feliks. 2016. Airbnb Is “Ravaging” Black Neighbourhoods in New York City and Trying to Hide It, Officials Say. The Independent. Available online at <http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/airbnb-ravaging-black-communities-new-york-city-a7000761.html>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Ghose, Rina. 2004. Big Sky or Big Sprawl? Rural Gentrification and the Changing Cultural Landscape of Missoula, Montana. Urban Geography 25 (6): 528–549.

Hackworth, Jason, and Smith, Neil. 2001. The Changing State of Gentrification. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 92 (4): 464-477.

Hammel, Daniel J. 1999. Gentrification and Land Rent: A Historical View of the Rent Gap in Minneapolis. Urban Geography 20: 116-45.

Hopkins, Jason. 2016. New York Rejects Free Market Innovation, Passes Law Killing Airbnb. Townhall. Available online at <http://townhall.com/tipsheet/jasonhopkins/2016/10/24/new-york-rejects-free-market-innovation-passes-law-killing-airbnb-n2236452>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Illegal Hotel Working Group. 2008. Room by Room: Illegal Hotels and the Threat to New York’s Tenants. Policy report.

Inside Airbnb. 2017. Inside Airbnb: New York City. Available online at <http://insideairbnb.com/new-york-city/>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Kalinowski, Tess. 2016. Renovated and Designed for Airbnb. Toronto Star. Available online at <http://startouch.thestar.com/screens/a2ef0481-be87-46b5-9e52-8a411281c29f%7C_0.html>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Lee, Dayne. 2016. How Airbnb Short-Term Rentals Exacerbate Los Angeles’s Affordable Housing Crisis: Analysis and Policy Recommendations. Harvard Law & Policy Review 10: 229-253.

Lees, Loretta. 2003. Super-gentrification: The Case of Brooklyn Heights, New York City. Urban Studies 40 (12): 2487-2509.

Lees, Loretta, Shin, Hyun Bang, and Lopez-Morales, Ernesto. 2016. Planetary Gentrification. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Litten, Kevin. 2016. Neighborhood 'Mourners' Want New Orleans Short-Term Rentals Regulated. The Times-Picayune. Available online at <http://www.nola.com/politics/index.ssf/2016/09/short_term_rental_demonstratio.html>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Samaan, Roy. 2015. Airbnb, Rising Rent, and the Housing Crisis in Los Angeles. Policy report prepared for the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy.

Morozov, Evgeny. 2016. Beware: Silicon Valley’s Cultists Want to Turn You into a Disruptive Deviant. The Guardian. Available online at <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/jan/03/hi-tech-silicon-valley-cult-populism>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

24

New York Communities for Change and Real Affordability for All. 2015. Airbnb in NYC: Housing Report 2015. Policy report.

Partnership for Working Families. 2016. Untitled letter to the Federal Trade Commission. Available online at <http://www.forworkingfamilies.org/sites/pwf/files/documents/FTC%20Short-Term%20Rental%20Letter_0.pdf>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Said, Carolyn. 2016. Airbnb, Under the Gun, Is Ready to Cooperate with SF. San Francisco Chronicle. Available online at <http://www.sfchronicle.com/business/article/Airbnb-under-the-gun-is-ready-to-cooperate-with-10612040.php>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Sigler, Thomas, and Wachsmuth, David. 2016. Transnational Gentrification: Globalisation and Neighbourhood Change in Panama’s Casco Antiguo. Urban Studies 53 (4): 705-722.

Slater, Tom. 2015. Planetary Rent Gaps. Antipode 49 (S1): 114-137.

------. 2009. Missing Marcuse: On Gentrification and Displacement. City 13 (2-3): 292-311. Slee, Tom. 2016. What’s Yours Is Mine: Against the Sharing Economy. New York: OR Books.

------. 2014. Sharing and Caring. Jacobin. Available online at <https://www.jacobinmag.com/2014/01/sharing-and-caring/>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Smith, Neil. 1996. The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City. New York and London: Routledge.

------. 1979. Toward a Theory of Gentrification: A Back to the City Movement by Capital, not People. Journal of the American Planning Association 45 (4): 538-548.

Stulberg, Ariel. 2016. Airbnb Probably Isn’t Driving Rents Up Much, At Least Not Yet. FiveThirtyEight. Available online at < https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/airbnb-probably-isnt-driving-rents-up-much-at-least-not-yet/>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Sundararajan, Arun. 2016. The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

US Department of Housing and Urban Development. 2016. Comprehensive Housing Market Analysis: New York City, New York. Policy report from the Office of Policy Development and Research.

Weise, Elizabeth. 2015. San Francisco Rejects Anti-Airbnb Measure. USA Today. Available online at <https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/2015/11/04/anti-airbnb-measure-fails-san-francisco/75138092/>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Wiedetz, Thorben. 2017. Squeezed Out: Airbnb’s Commercialization of Home-Sharing in Toronto. Policy report prepared for FAIRBNB.CA Coalition.

Woolf, Nicky. 2016. Airbnb Regulation Deal with London and Amsterdam Marks Dramatic Policy Shift. The Guardian. Available online at <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/dec/03/airbnb-regulation-london-amsterdam-housing>. Last accessed July 4, 2017.

Zervas, Georgios, Prosperio, Davide, and Byers, John W. 2016. The Rise of the Sharing Economy: Estimating the Impact of Airbnb on the Hotel Industry. Journal of Market Research. Available online at <https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.15.0204>.