Africa’s Turn A New Green Revolution for the 21st Century

Transcript of Africa’s Turn A New Green Revolution for the 21st Century

Africa’s TurnA New Green Revolution for the 21st Century

THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION § JULY 2006

TM

ver the course of nearly fourdecades, beginning in the 1940s,annual crop yields surged in poor

countries around the world. Between 1960and 1985 cereal yields, total cereal produc-tion, and total food production in developingcountries all more than doubled. Dubbed the“Green Revolution” by an American foreign-aid official, this historic transformation oftraditional farming methods began with asingle public-private experiment with Mexi-can wheat. It quickly spread to corn, beans,and rice, rippling across hundreds of millionsof cultivated acres throughout Latin Americaand Asia. The change was particularly pro-nounced—life-altering and frequently life-

saving—on the small farms where nearly halfa billion of the world’s poorest people madetheir living.

The roots of this achievement were a com-bination of venturesome philanthropy, astuteagricultural research, aggressive recruitmentand training of scientists and farmers in thedeveloping world, and determined govern-ment agricultural and water policy. The resultswere as massive as they were unprecedented.

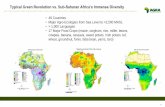

What they were not was universal. TheGreen Revolution stopped at Africa.

To be sure, hunger and hard, volatile farm-ing aren’t limited to any one continent. Nordid the Green Revolution bestow a uniformblessing on all other parts of the world. Evenin South Asia, where the Green Revolutionyears saw so much growth, portions of theregion still suffer from widespread hunger andrural poverty. But given the size of sub-Saha-ran Africa, the predominance of small-scalefarming among its main industries, the inter-national attention devoted to the region, andthe extent of its poverty and hunger, it is par-ticularly disheartening that little of the bene-fits from a worldwide upheaval in agriculturetook root there. Sub-Saharan Africa, whichcontains 16 of the 18 most undernourishedcountries in the world, remains the onlyregion where per-capita food production con-tinues to worsen year by year.

Tororo district, Uganda.

Africa’s TurnA New Green Revolution for the 21st Century

O

There are many reasons for this gigantic gapin the benefits of the Green Revolution. Butmore to the point, there is good reason toimagine closing that gap—reasons thatinclude advances in all the fundamentals thatmade up the original achievement: science,training of local practitioners, public-privatecooperation, and improvements in govern-ment policy and practice. It is time for a sec-ond Green Revolution, aimed squarely atAfrica. But before building a case for a goal ofthat scale, it is worthwhile to consider how thefirst Green Revolution got its start, and howits initially modest ambitions grew to becomeone of the signal peaceful achievements of the20th century.

An act of leadershipBefore all else, the original Green Revolutionwas a product of philanthropy, in a carefullynegotiated partnership with government. Thepartnership began in Mexico and expanded toColombia, India, the Philippines, and fartherinto Latin America and Asia. Its first manifes-tation was a modest research center outsideMexico City, formally lodged in the Mexicangovernment but managed, staffed, and mostlyfunded by the Rockefeller Foundation. Theidea started with a casual comment in 1941 byHenry Wallace, then Vice-President of theUnited States, to Rockefeller President Ray-mond B. Fosdick: Increase the yield per acreof corn and beans in Mexico, and you woulddo more for the country and its people thanby any other means. (The same might now besaid, 60 years later, about crops in Africa.)

Intrigued, Fosdick consulted the RockefellerBoard, hired three eminent agricultural scien-tists to scope out the possibilities, and organ-ized a research and development operation.After first seeking and receiving an invitationfrom the Mexican government, the Foundationcreated the Oficina de Estudios Especiales withinthe Mexican Department of Agriculture, ini-tially staffed by scientists on the Rockefellerpayroll. Among the pioneers in this effort wasplant pathologist Norman Borlaug, whoremained a Rockefeller Foundation officer forthe next 39 years. He won the Nobel PeacePrize for his Green Revolution work in 1970.

[2] Sub-Saharan Africa, with 16 of the 18 most undernourishedcountries in the world, remains the only region where per-capitafood production continues to worsen year by year.

Norman Borlaug.

[3]Before all else, the original Green Revolution was a product of philanthropy, in a carefully negotiated partnership with government.

By the end of the decade, the Mexican gov-ernment had supplemented the Foundation’ssmall research team with 79 Mexican scientistsand agronomists, many of whom went on topostgraduate study in the United States onRockefeller scholarships. The Foundation thenbegan drawing Latin American agricultural fel-lows to the Oficina from universities it wassupporting elsewhere in the hemisphere. Bythe time Fosdick had retired and completed ahistory of the Rockefeller Foundation in 1952,he was already noting evidence of an interna-tional bandwagon:

News of this cooperative undertakingspread rapidly to other countries. It traveledby word of mouth from the returning fel-lows, visiting professors, and others who

had personal contact with the project, andby the printed word of technical papers andother publications reporting the results ofthe researches and their application to cropimprovement. Eventually, inquiries beganto come from other Latin American coun-tries, …inviting the Rockefeller Founda-tion to collaborate. …Reports from Asiaindicate that accounts of what was done inMexico have circulated there.

In 1957, the Rockefeller Foundation starteda similar country program in India and threeyears later the Rockefeller and Ford Founda-tions jointly created the International RiceResearch Institute at Los Baños in the Philip-pines. These two steps opened an Asian frontin the spreading revolution, which continuedaccelerating for decades.

Borlaug with students in wheat field, Mexico, 1964.

[4]

The point of this story is not to relive a dis-tant chapter of foundation history. The pointis that the Green Revolution was not solely atriumph of unfettered science, Westernlargesse, or the free market—three of thefavorite solutions in much of the populardebate over Africa today. It was, at its origins,a strategic act of philanthropy, enlistingexperts, government, and ultimately localscholars and farmers in a carefully wroughtpartnership that grew geometrically—anddeliberately—over many years. Science, dona-tions, and market forces all played an indis-pensable part; but all were guided, in the firstinstance, by a philanthropic plan.

A similarly decisive initiative from philan-thropy—perhaps even more challenging thanthe first Green Revolution, but surely withinthe means of today’s foundation commu-nity—could well spark a new Green Revolu-tion, this time for Africa. As in the firstinstance, success is far from assured. Africa is amore complex challenge from those faced bythe earlier revolutionaries. Still, the basic ele-ments of the first Green Revolution still apply,at least in broad strokes, to the needs ofAfrican farmers today: scientific developmentof more productive crops and fertilizers; culti-vation of local talent in plant science, farming,agricultural policy, and business; strong com-mitment from national governments; andpublic-private collaboration on infrastructure,water and irrigation, the environment, andbuilding markets for the inputs and outputs ofa revolutionized farm sector.

Where the next revolution beginsConsider a typical African smallholder farmer,one of 180 million across the sub-Saharanregion. She (many are women, virtually all areheads of individual families) farms onehectare of land, the size of an American cityblock. The farm is largely a subsistenceoperation. In good years, a small surplusmight be bartered or sold locally, but thereare likely no warehouses or processingcompanies to preserve excess crops for latersale, and transportation to city markets overpoor roadways is difficult, costly, time-consuming, and sometimes dangerous. Thereis no irrigation and probably little or nochemical fertilizer; the farm depends onnature for water and fertility. In a bad year,due to any combination of pestilence, disease,environmental degradation, drought, or otherhostile weather, the farmer and her family willgo hungry. This precarious existence is neitherrare nor extreme by sub-Saharan standards:60 percent of all Africans work in agriculture,

Africa is a more complex challenge from those faced by earlier revolutionaries.

Maize field, Uganda.

and three-fifths of their farms are small, runmainly for subsistence. Half the population ofsub-Saharan Africa earns the equivalent of 65cents a day on average.

On this typical farm, the children are anessential part of the workforce. If they arelucky, they may go to school for a few hours aday, but most family farms require all hands.Long days of stoop labor, meager nutrition,and rampant disease, including tuberculosis,malaria, and AIDS, make life expectanciesshort and pose a constant threat to the farm’soperation and the family’s survival. With fewskills and no disposable resources, childrenhave scant hope of migrating to cities andfinding non-farm employment. If they surviveto adulthood, most will have to start newfarms—either on a small piece of land theyreceive from their family or by expanding thecultivation of land farther and more often,inefficiently and unsustainably.

A main reason for the inefficiency is thatthe crops on the great majority of small farmsare not the high-yielding varieties in commonuse on other continents. A small African farm

is less than one-third as likely to use suchcrops as one of its Asian counterparts. Thusthe only way to grow more and support morefamilies is to cultivate more land. Yet thatstringent arithmetic suggests a latent opportu-nity: If better seeds could reach this farmer,along with techniques for using them effec-tively, the inefficiency and risk of food short-ages could be reduced or eliminated. In time,the farm could be converted from subsistenceto surplus, with the additional harvest avail-able for sale, locally or regionally. Still greateryields would come from improved fertilizer,given the right combination of seeds, soil, andadded nutrients.

But the challenge of bringing higher-yield-ing seeds to Africa’s small farms is more com-plicated than it was in the earlier GreenRevolution. Among other factors, Africa’s cli-mate, soil, and range of suitable crops are allfar more diverse than in Asia or Latin Amer-ica. In addition, irrigation was far more wide-spread in Asia than it is in Africa, and there arefewer teams of trained scientists available towork in large breeding programs.

Yet it is possible to develop higher-yieldingcrops suitable to Africa’s various regions, par-ticularly if the region’s farmers are part of thebreeding, testing, and selection process. It ispossible to deliver these superior seeds to farm-ers, and to help them use the seeds effectively.In fact, all of these things are already beingdone, at least in select regions. The process isnecessarily more decentralized than in the firstGreen Revolution, with many breeding pro-grams working on many more niche environ-ments, in close collaboration with local

[5]A main reason for the inefficiency [of farming in Africa] is thatthe crops on the great majority of small farms are not thehigh-yielding varieties in common use on other continents.

Children at daybreak, Kenya.

farmers. Extending this enterprise across all ofsub-Saharan Africa would take time, signifi-cant investment, and particular effort torecruit and train generations of African scien-tists. Africa’s version of a Green Revolutionmay not be as immediate and sweeping as theearlier one, but it could be just as profound,with consequences every bit as life-saving.

Early milestones in raising yieldsThe idea is neither hypothetical nor farfetched.The Rockefeller Foundation’s six-year-old pro-gram on improved crop varieties for Africa hashelped establish a credible, promising beach-head on all these fronts, at least in parts of thecontinent, primarily in the east and south.Relying on grants to African and multinationalorganizations, for projects led primarily byAfrican scientists, the Foundation has sup-ported the development and release of morethan 100 new crop varieties, dozens of whichare already in use. One example among manyis the breeding of a breakthrough rice varietythat stands up to the particular challenges fac-ing rice farmers in Africa’s upland regions—including weeds, drought, pests, and diseasesthat have hindered African rice cultivation forcenturies. Since the new varieties reached themarket in the late 1990s, they have provenboth popular and successful. Known as NewRice for Africa, or Nerica, the various strainsare now cultivated on more than 300,000 acresacross the continent. Besides the benefits forthe food supply and farm incomes, the spreadof Nerica has had a measurable, far-reachingsocial effect: The rice’s shorter growth cycleand strength against weeds has boosted schoolattendance among children who are now lessneeded in the fields.

Given the need for local specificity in devel-oping seeds, a critical element of crop-breedingprograms is the recruitment and training ofAfrican scientists familiar with the circum-stances of the particular areas where they work.Many of the scientists working on the Rocke-feller-sponsored projects grew up on farmssimilar to the ones with which they are nowworking. The Foundation is supporting some25 crop-breeding teams working within vari-ous national agricultural research institutes, aswell as the training of about 50 students pur-suing doctoral degrees in plant breeding andanother 30 to 40 completing master’s degrees.Though this is barely a start on the total num-ber of scientists needed for a full-scale GreenRevolution in Africa, the influx of new talentwill make it possible to triple or even quadru-ple the number of national breeding programsover the next several years.

[6]

Biotech lab, National Agricultural Research Organization, Uganda.

In addition to better seeds, another essen-tial element of the first Green Revolution wasthe widespread use of better fertilizers. Butthis, too, is an area in which the challenges ofa second Green Revolution will be steeperthan in the first. In Africa, where roads arepoor and rail and waterways scarce, by thetime fertilizer reaches a small farm, trans-portation costs alone will have driven its priceto more than twice the world market level—far beyond the means of most subsistencefarmers. Government trade policies, taxes,and other factors often push the price evenhigher. Fortunately, the attention of publicand private organizations to this issue haslately grown much more intense, as evidencedby the Africa Fertilizer Summit in June 2006in Abuja, Nigeria. One significant outcomeof the Summit: More than 40 national gov-ernments agreed to lift all cross-border taxesand tariffs on fertilizer. Various pledges andagreements sought to strengthen the nascent

industry of “agro-dealers”—village retailerswho sell seeds, fertilizer, and farm tools—tobuild market mechanisms for helping farmersbuy better inputs and learn how to use them.Participants in Abuja also agreed to establishan African fertilizer-financing mechanismwithin the African Development Bank, start-ing with a $10 million pledge from Nigeria,to finance the various efforts that the Summitset in motion.

The growth of the “agro-dealer” industry isworth a particular note. Across a vast, sparselypopulated landscape, the distribution of farminputs and the knowledge of how to use themcan be prohibitively difficult. Agriculturalextension, a mainstay of farmer education andtechnology transfer in the West, is still a rudi-mentary system, at best, in most of Africa. Butby training village merchants in the basics ofretailing farm supplies—including how tohelp farmers understand and use the prod-ucts—and by helping them finance their busi-nesses with loan guarantees and other creditsupport, Rockefeller Foundation grantees havecultivated a new market sector that strengthensboth small retailers and small farmers.

[7]In addition to better seeds, another essential element of the first Green Revolution was the widespread use of better fertilizers.

Farmer examining harvested beans, Kenya.

Beyond the farmIt would be a significant achievement, wellworth pursuing on its own, just to reduce thehardships of subsistence farming and improveyields enough to lower the chronic risk ofshortages and starvation. But a real GreenRevolution would embrace a more expansivevision. Imagine that an eventual increase inharvests, due to superior seeds and nutrients,along with generally better farming practices,eventually results in regular surpluses. Howwould the additional crops get to market?How could they be stored and preserved inthe meantime; who would process and other-wise add value to them? A successful revolu-tion in African agriculture would depend onthe growth of stronger market systems, better

infrastructure, and the technology to makethe various transactions efficient. In most ofAfrica, all these essentials are still rudimentaryat best.

Yet it is possible to imagine, over time,breaching most of these later-stage obstacles.As with crop breeding, the Rockefeller Foun-dation’s early experience in supporting mar-kets, cooperatives, and small enterprise inrural Africa suggests an opportunity to do agreat deal more. Foundation grants have metwith some success in helping farmers formcooperatives to store, transport, and markettheir produce. Microfinance and agriculturallending programs have grown in recent years,also with help from foundations and other

[8] Imagine that an eventual increase in harvests…results in regular surpluses. How would the additional crops get to market?

Bugoma Cereal Bank, Kenya.

donor agencies, though the need is still mostlyunmet. A few public and international devel-opment programs have contributed toimprovements in infrastructure, though thisremains a huge challenge. Business-friendlypolicies to encourage the formation of pro-cessing, trucking, and equipment enterprises,among many other market essentials, are stillless common in Africa than they need to be,though they have shown progress where theyhave been pursued.

These are all areas in which partnershipswith African governments, involving philan-thropy, other international donor and financeorganizations, and private industry, could bepowerfully influential. Although the firstGreen Revolution did not confront quite sobroad a mix of variables, it did rest on preciselythe kind of public-private partnership throughwhich many of Africa’s current problems couldbe effectively addressed. The Fertilizer Summitis an example of just such an undertaking: Itwas convened by an African developmentorganization under the leadership of a head ofstate, and sponsored by a broad partnershipincluding the Rockefeller Foundation, theBritish Department for International Develop-ment, four prominent international agricul-tural development organizations, and twointernational fertilizer trade groups. And itdrew participation from roughly two-thirds ofAfrica’s national governments.

The challenge in briefThe vision of a new Green Revolution forAfrica is a single challenge in several layers.At the most fundamental level is improvedseed varieties for larger, more diverse, andmore reliable harvests. That requires not onlyan astute application of science, but thedevelopment of new generations of trainedAfrican agricultural scientists.

A second tier involves better inputs andpractices, including the use of fertilizer andother soil and water management techniques.Part of this challenge is the development of amore robust market for bringing new prod-ucts to farmers in a manner—likely through“agro-dealers”—that enables the farmers toput the innovations to use.

Next up the ladder is the development ofstronger off-farm systems and markets, fromstorage to transportation to processing and finalsale. Though this is a more complex and wider-ranging task than the others (and moredemanding than anything directly pursued inthe first Green Revolution), it represents per-haps the greatest opportunity for a fundamentaltransformation in Africa’s agricultural economyand the future livelihoods of poor farmers.

[9][T]he Rockefeller Foundation’s early experience in supportingmarkets, cooperatives, and small enterprise in rural Africasuggests an opportunity to do a great deal more.

Also beyond the farm would be the greatcapital challenges of better infrastructure and,where possible, larger irrigation systems.Although these are not areas in which theRockefeller Foundation has made significantinvestments, both are subjects of increasinginquiry and investment by others. Supportivenational policy reforms can also play animportant role.

Most of all, underlying all of this, is theessential challenge of forging strong andexpanding partnerships, with a decisive lead-ership from institutions and governments,both in Africa and elsewhere, that are willingto get started and pursue the vision. That wasthe indispensable beginning of the first GreenRevolution. There will likely be no second onewithout an exertion of similar determinationand path-breaking investment. That processseems to be starting. Drawing the current,promising efforts into a coherent whole, sup-plementing them with further investment anda wider circle of partnerships, and pursuingthem determinedly over a long term couldspark the first great peaceful revolution of the21st century.

[10]

Tororo District, Uganda.