Acute Magnesium Administration Frequency of … animportant catalyst ofmanyenzymatic reactions in...

Transcript of Acute Magnesium Administration Frequency of … animportant catalyst ofmanyenzymatic reactions in...

660

Effect of Acute Magnesium Administration onthe Frequency of Ventricular Arrhythmia in

Patients With Heart FailureCarla A. Sueta, MD, PhD; Susan W. Clarke, BSN; Stephanie H. Dunlap, DO;

Lynda Jensen, MT; Mary Beth Blauwet, MS; Gary Koch, PhD;J. Herbert Patterson, PharmD; Kirkwood F. Adams, Jr, MD

Background There is a high incidence of ventricular ar-rhythmia and sudden death in patients with heart failure.Unfortunately, currently available antiarrhythmic agents haveonly limited efficacy and may result in proarrhythmia andhemodynamic deterioration in these patients.Methods and Results We studied the acute effect of intra-

venous magnesium chloride on the frequency and severity ofventricular arrhythmia in 30 patients with symptomatic heartfailure using a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover de-sign. The left ventricular ejection fraction was 23.0+8.0%(mean±SD). No patient had a history of symptomatic ventric-ular arrhythmia or was receiving antiarrhythmic agents, cal-cium channel antagonists, or P-blockers. Patients were ran-domized to receive placebo (5% dextrose [D5W] in wateralone) or magnesium chloride in D5W given as a bolus of 0.3

C ongestive heart failure is characterized by con-tractile dysfunction, frequent complex ventric-ular ectopy, and a high incidence of sudden

death. Unfortunately, currently available antiarrhyth-mic agents have only limited efficacy in patients withcongestive heart failure and may be associated withworsening ectopic activity and hemodynamic deteriora-tion. Magnesium is a ubiquitous divalent cation thatstrongly influences cardiac cell membrane function andis an important catalyst of many enzymatic reactions inthe myocyte. Alterations in extracellular or intracellularmagnesium concentration could significantly influencethe development and frequency of ventricular arrhyth-mia in patients with heart failure. These patients arepredisposed to magnesium deficiency secondary to di-uretic and digoxin administration, neurohormonal acti-vation resulting in volume expansion, and poor oralintake and absorption.1 Ventricular arrhythmia mayarise in heart failure as a result of enhanced automatic-ity or triggered activity. Experimental studies suggestthat magnesium administration may reduce or preventthe occurrence of ventricular arrhythmia induced bythese mechanisms.23 A beneficial effect of magnesium

Received July 23, 1993; revision accepted November 6, 1993.From the Departments of Medicine and Radiology, School of

Medicine, the Department of Biostatistics, School of PublicHealth, and the School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolinaat Chapel Hill.Correspondence and reprint requests to Carla A. Sueta, MD,

PhD, Division of Cardiology, University of North Carolina atChapel Hill, CB# 7075, Burnett-Womack Bldg, Chapel Hill, NC27599-7075.

mEq/kg over 10 minutes followed by a maintenance infusion of0.08 mEq/kg per hour for 24 hours. The magnesium concen-trations 30 minutes and 24 hours after the bolus were 3.6+0.1and 4.2±0.1 mg/dL, respectively. There was no significantchange in serum potassium concentration during magnesiumadministration. Blinded analysis revealed that administrationof intravenous magnesium chloride, compared with placebo,significantly decreased total ventricular ectopy per hour(mean±SEM, 70±26 versus 149±64. P<.001), couplets perday (23±11 versus 94+59, P=.007), and episodes of ventricu-lar tachycardia per day (0.8±0.2 versus 2.6±1.0, P=.051).

Conclusions Intravenous magnesium chloride administrationreduces the frequency of ventricular arrhythmia in patients withsymptomatic heart failure. (Circulon. 1994;89660-666.)Key Words * magnesium * arrhythmia * heart failure

on complex ventricular ectopy in patients with heartfailure could have important consequences because thisarrhythmia may culminate in ventricular fibrillation andsudden death.

Despite the potential for therapeutic benefit, thereare few studies of the antiarrhythmic effect of paren-teral magnesium in heart failure,4-8 and to the best ofour knowledge, a randomized, placebo-controlled trialhas not been performed. Therefore, we prospectivelyinvestigated the antiarrhythmic effect of acute magne-sium infusion using a randomized, double-blind, place-bo-controlled crossover design. Our hypothesis was thatacute augmentation of serum magnesium concentrationwould reduce the frequency and severity of ventriculararrhythmia in patients with symptomatic congestiveheart failure.

MethodsEligibility and Exclusion

Study subjects were recruited prospectively by review ofpatients seen by the Heart Failure Program at the Universityof North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Inclusion criteria includedage of 18 years or older, left ventricular ejection fraction.40% by radionuclide ventriculogram, presence of heartfailure for at least 1 month, New York Heart Association(NYHA) class II to IV, and normal sinus rhythm. Exclusioncriteria included a history of symptomatic ventricular ectopy,antiarrhythmic drug therapy (procainamide, quinidine, disopy-ramide, phenytoin, tocainide, mexiletine, ethmozine, flecain-ide, encainide, propafenone, amiodarone, sotalol), calciumchannel antagonists, /3-blockers, a PR interval >0.2 seconds,or a serum creatinine >2 mg/dL. Digitalis use was not an

by guest on April 16, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

Sueta et al Magnesium and Ventricular Arrhythmia in Heart Failure 661

exclusion criterion. The protocol was approved by the Institu-tional Review Board of the University of North CarolinaSchool of Medicine, and written consent was obtained from allpatients before study entry.

Study DesignThis study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-con-

trolled crossover trial requiring 4 days of hospitalization in theGeneral Clinical Research Center. The sequence was base-line-magnesium-washout-placebo or baseline-placebo-day3-magnesium. Day 1 (baseline) included a cardiac history,physical examination, blood chemistry determination, serumdigoxin concentration, and a 12-lead ECG. All patients weremonitored by telemetry and Holter throughout the study. Onday 2, a peripheral heparin lock was placed for blood drawing,and a second peripheral intravenous line was placed for theadministration of the randomized treatment. After determina-tion of blood chemistries, the subject was given a bolus dose ofmagnesium chloride (0.3 mEq/kg) in 5% dextrose (D5W) inwater or placebo (D5W alone) over 10 minutes followed by acontinuous infusion of magnesium chloride (0.08 mEq/kg perhour) or placebo for 24 hours. Eight subjects were dosed onthe basis of lean body weight because of obesity. Lean bodyweight in kilograms was calculated as 45.5 (women) or 50(men) plus (2.3 multiplied by inches above 5 feet).9 Bloodpressure and heart rate were recorded at baseline and at 2, 4,6, 8, 10, 15, 20, and 30 minutes and at 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 5, 7, 12, and24 hours. Serum magnesium concentrations were determinedat baseline, at the end of the bolus (10 minutes), and at thefollowing intervals: 15, 20, and 30 minutes and 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 5, 7,12, and 24 hours. In a subset of 14 patients, serial potassiumconcentrations were also obtained. On day 3 (washout day forthe subjects who received magnesium on day 2), a bloodsample for electrolytes was taken, and Holter monitoring wascontinued. On day 4, the protocol was the same as on day 2except that the alternate therapy was given to complete thecrossover design. On day 5, the subject had a final bloodsample taken and was discharged.

Magnesium AnalysisOne milliliter of whole blood was centrifuged at 1200g for 5

minutes. The supernatant was removed, and the concentrationof magnesium in the serum was determined by atomic absorp-tion spectrophotometry.10

Ambulatory ECG RecordingAmbulatory ECG monitoring was performed with an Ox-

ford MR20 two-channel (leads V, and V5) AM recordingdevice. The Holter tape recordings were analyzed on a fulldisclosure unit (Oxford) that printed out each individual QRScomplex for subsequent visual examination. Complete deter-mination of premature ventricular contraction (PVC) fre-quency with description and quantification of complex forms(multiform PVCs, couplets, and ventricular tachycardia) wasundertaken for each hour of the monitoring period by manualanalysis of the full disclosure data. Time representing artifactwas subtracted from each hour of the recording so that themeans per hour reflected only time for which interpretationwas possible. A minimum of 18 hours per day of usable datawas required, on both the treatment and placebo days, toinclude a tape in the data analysis. Full-scale real-time tracingsof calibration signals, a period of baseline rhythm, and eachepisode of ventricular tachycardia were printed. A physicianinvestigator (C.A.S.) verified all episodes of ventricular tachy-cardia on days 2 and 4. Counts of PVCs per hour and coupletsper day in a 10% sample of the study data were also verified bythe same investigator. Intraclass correlations between the twoobservers were high between counts for total ventricularectopic beats (r=.99), couplets (r=.99), and the number ofepisodes of ventricular tachycardia (r=.99). The technician

and physician were blinded as to the identity of the recordingunder analysis.For the purpose of this study, total ventricular ectopy was

defined as the mean number of PVCs per hour, including thepremature beats in couplets and episodes of ventricular tachy-cardia. Ventricular tachycardia was defined as .3 consecutivepremature ectopic beats at a rate of >100 beats per minute.Ventricular tachycardia was judged to be sustained if theduration was >30 seconds or if it resulted in hemodynamiccompromise requiring intervention with either medication orcardioversion. The rate and duration (number of beats) ofeach episode of ventricular tachycardia were determined.

Statistical AnalysisThe present study was designed to take into account the

spontaneous variability of ventricular arrhythmia. The studysample size of 30 was estimated to have at least an 80% powerto detect a target difference of 50% in arrhythmia frequencybetween the magnesium and placebo days. The results areexpressed as mean±SEM unless otherwise indicated. TheWilcoxon signed-rank test was used for statistical comparisonsof the frequency of ventricular arrhythmia and of the fastestrate and longest duration of episodes of ventricular tachycar-dia between monitoring periods. The presence of a periodeffect (exposure x day) or a carryover effect was determinedby the Wilcoxon rank-sum test."1 The possibility of a carryovereffect was analyzed in two ways. The differences between theaverage ventricular ectopy over two treatment periods (mag-nesium and placebo) and baseline (day 1) for both sequenceswere compared. Additionally, the differences between ventric-ular ectopy on washout and baseline days were compared foreach sequence.Blood pressure, heart rate, and electrolyte levels during

magnesium and placebo infusion were compared by pairedStudent's t test. The trapezoidal rule was used to determinethe area under the curve for magnesium and potassium serumconcentrations on placebo and magnesium days. This methodaverages two adjacent values and multiplies them by thedistance between the two values. These individual areas aresummed to produce an overall area under the curve. Subjectswere included if they had at least 50% of the serum electrolyteconcentration data points. Interpolation was used to supplymissing values. Spearman rank correlation coefficients wereused to test the strength of the relation between the differencein ventricular arrhythmia frequency on magnesium and pla-cebo days and various study variables.

ResultsStudy PatientsThe protocol was successfully completed by 30 of the 35

patients who were enrolled. Incomplete Holter monitor-ing excluded 2 patients, and heart failure exacerbationbefore randomization excluded 2 other patients. Onediabetic patient developed symptomatic hypoglycemia onthe placebo day and was excluded from analysis. Therewere 21 men and 9 women aged 49±+-9.6 years(mean+SD). The etiology of heart failure was predomi-nantly nonischemic. Heart failure was secondary to hyper-tension and/or alcohol abuse in 19 subjects (1 subject alsohad sarcoidosis) and to coronary artery disease in 4 andwas idiopathic in 7 subjects. All subjects had clinicalevidence of heart failure, with 70% being NYHA class IIand 30% being class III. Left ventricular ejection fractionwas significantly depressed at 23±8.0% (mean+SD), witha range of 9% to 38%. At the time of the study, all of thesubjects were receiving an angiotensin-converting enzymeinhibitor and digoxin, and 97% (29 of 30) were receivingdiuretic agents. Potassium supplementation was beinggiven in 48% of the patients (14 of 29) who were receiving

by guest on April 16, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

250

200

z.

4

150 -

100 -

50 -

0-

* PLACEBO

E MAGNESIUM

PVC/HR COUPLETS/DAY

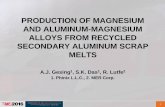

1 9 5 9 9 1 a 9 5g g | § | FIG 2. Bar graph shows the frequency (mean±SEM) of total0 4 8 1 2 1 6 2 0 2 4 premature ventricular contractions per hour (PVC/HR) and coup-

TIME (HOURS) lets per day on placebo (solid bar) and magnesium (hatchedLph shows serum magnesium concentration bar) days in 30 subjects with heart failure. An asterisk indicates

p) before (time=O) and aser magnesium infusion a statistically significant difference (P<.01) between placebo andbefoe (ime0) nd fte manesum nfuion magnesium days.

diuretic agents. Other cardiac medications included ni-trates and clonidine in 3 subjects each. Magnesium sup-plementation was discontinued in 2 patients before studyentry. In the 2 patients enrolled who had pacemakers,pacer spikes were detectable on the Holter record but didnot interfere with the determination of ventricular ectopy.Baseline serum magnesium, potassium, creatinine, cal-cium, and digoxin concentrations were 2.0+0.1 mg/dL,4.2±0.1 mmol/L, 1.2±0.04 mg/dL, 9.1+0.1 mg/dL, and0.9±0.1 ng/mL, respectively. Two patients were hypo-magnesemic (<1.5 mg/dL) before receiving the magne-sium infusion, and 1 of these patients was also hypokale-mic (3.2 mmol/L).

Baseline Ventricular EctopyThere was wide variability in the degree of baseline

(day 1) ventricular ectopy among the study subjects. Thetotal number of PVCs per hour ranged from 0.04 to 680,with a mean of 110±f30 and a median of 54. The averagenumber of couplets per day was 80±31, with a range of0 to 711 and a median of 18. Couplets were detected in86% (25/29) of patients. Ventricular tachycardia was

present in 62% (18/29) of patients. The average numberof episodes of ventricular tachycardia per day was

2.3+0.9, with a range of 0 to 23 and a median of 1.0.

Magnesium AdministrationFor the group as a whole, the preinfusion serum

concentration of magnesium was higher on the placeboday compared with the magnesium day, 2.2±0.1 mg/dLversus 2.0±0.1 mg/dL, respectively (P=.037). In the 16subjects given magnesium on day 2, the preinfusionserum concentration of magnesium was significantlyhigher on the placebo day than the magnesium day(2.2+0.1 mg/dL versus 2.0±0.1 mg/dL, P<.01). Bycontrast, preinfusion serum magnesium concentrationwas similar on the magnesium and placebo days(2.1+0.1 mg/dL versus 2.0±0.1 mg/dL, P=NS) whenmagnesium was given on day 4. The total dose ofmagnesium chloride administered was 163±33 mEq(mean+SD), with a range of 117 to 258 mEq. Fig 1shows the serum concentration of magnesium before

(time 0) and during the magnesium infusion. The serum

magnesium concentration was significantly increasedover the entire 24-hour infusion period, calculated as

area under the curve (n= 14), compared with placebo(P=.001). Serum magnesium concentration was 3.6±0.1mg/dL 30 minutes after the bolus (n=13) and 4.2±0.1mg/dL after 24 hours (n=19) compared with placebo(P<.001).The preinfusion serum concentration of potassium

was 4.3±0.1 mmol/L (n=27) on the placebo and mag-

nesium days. In a subset of patients, serum potassiumconcentrations were not significantly different at 30minutes (n=8) or 24 hours (n=9) after magnesiuminfusion compared with placebo. There was also no

significant difference between potassium concentrationon the magnesium and placebo days calculated as areaunder the curve (n=8).

Magnesium and Ventricular ArrhythmiaThe infusion of intravenous magnesium chloride sig-

nificantly decreased the total number of PVCs per hourby 53% (70±26 versus 149+64, P<.001) compared withplacebo (Fig 2). More complex forms of ventriculararrhythmia were also reduced during magnesium infu-sion, including couplets per day by 76% (23± 11 versus94±59, P=.007) and episodes of ventricular tachycardiaper day by 69% (0.8±0.2 versus 2.6+1.0, P=.051) (Figs2 and 3). In the 9 patients who had episodes ofventricular tachycardia on both the placebo and mag-nesium days, the rate of the fastest run was significantlyreduced on the magnesium day compared with placebo(143±7 versus 179±8 beats per minute, P=.008). Thelongest episode of ventricular tachycardia also tended todecrease on the magnesium day (5±1 versus 9±2 beatsper minute), but this did not attain statistical signifi-cance (P=.211).

Figs 3 and 4 show ventricular ectopy on each day ofthe protocol. There was no significant difference inventricular ectopy on the placebo day compared withbaseline or washout days. Because washout representedday 3 in the 16 patients who received magnesiuminfusion on day 2, no carryover effect was observed.

662 Circulation Vol 89, No 2 February 1994

4.]

32

2-

W _Z -

_j00

C')

FIG 1. Gra(mean±SEM(n=24 to 29)

1

l

by guest on April 16, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

Sueta et al Magnesium and Ventricular Arrhythmia in Heart Failure 663

4 -

3-

2-

-X0Cn,W

0

U)

CLW

0

cc

m

z

O -

BASELINE PLACEBO MAGNESIUM WASHOUT

DAY

FIG 3. Bar graph shows the frequency (mean±SEM) of epi-sodes of ventricular tachycardia (VIT) on baseline (n=29), pla-cebo (n=30), magnesium (n=30), and washout (n= 16) days. Anasterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (P<.051)between magnesium and placebo or baseline days.

Magnesium infusion resulted in a significant reductionin ventricular arrhythmia whether administered on day2 or day 4. The Table shows the frequency of total PVCsand couplets per hour during successive time intervalson the washout day compared with the magnesium day.As serum magnesium concentration declined on thewashout day, total ventricular ectopy and couplets perhour gradually increased compared with the magnesiumday (P<.05).When the 2 subjects who were hypomagnesemic

and/or hypokalemic were excluded from the analysis,magnesium administration still resulted in a significantreduction in total ventricular ectopy per hour (P=.001)and couplets per day (P=.014) but not in episodes ofventricular tachycardia per day (P=.108). There was no

significant relation between the change in total ventric-ular ectopy and the preinfusion serum magnesium(n=29; r=-.11, P=.558) or potassium concentration(n=30; r=.24, P=.211). The change in serum potassiumconcentration during the infusion of magnesium, calcu-

300 -

a.0

C.)

zcccz

200 -

100-

o -

MEAN PVC/HR

E COUPLETS/DAY

T

T

BASELINE PLACEBO MAGNESIUM WASHOUT

DAY

FIG 4. Bar graph shows the frequency (mean+SEM) of totalpremature ventricular contractions per hour (PVC/HR) (solid bar)and couplets per day (hatched bar) on baseline (n=29), placebo(n=30), magnesium (n=30), and washout (n=16) days. Anasterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (P<.01)between magnesium and placebo, baseline, or washout days.

lated as area under the curve (n=8), also did notcorrelate with the degree of reduction of total PVCs perhour (r= -.38, P=.352), couplets per day (r= -.36,P=.385), or episodes of ventricular tachycardia per day(r= -.37, P=.365). Therefore, all subjects were includedin the primary analysis.No subject developed hemodynamically significant

ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, or tor-sades de pointes during the magnesium infusion. Onesubject who did not demonstrate ventricular tachycardiaon the placebo day had one episode of sustained butasymptomatic ventricular tachycardia (156 beats at arate of 120 beats per minute) during magnesium infu-sion. This same subject also had three episodes ofnonsustained ventricular tachycardia on the baselineday and one episode on the washout day. In 1 othersubject, mean PVCs per hour increased by more thanfourfold during magnesium administration comparedwith placebo, meeting the definition of proarrhythmiaadopted by the CAPS investigators.12 However, ventric-ular arrhythmia variability in this patient was high, andif ventricular ectopy on baseline and placebo days wereaveraged, no proarrhythmia was observed.

Effect on Blood Pressure and Heart RateSystolic and diastolic blood pressure and heart rate

before magnesium infusion were 113+ 15 mm Hg, 70± 10mm Hg, and 78±12 beats per minute (mean±SD), respec-tively. Intravenous administration of magnesium chloridedid not affect systolic or diastolic blood pressure. Heartrate transiently increased by 9% during the magnesiumbolus compared with placebo (75±12 versus 82+10 beatsper minute, P<.02). After completion of the bolus, therewere no differences in heart rate between magnesium andplacebo days over the following 24 hours.

Adverse EffectsTransient flushing (n= 12), burning at the intravenous

site (n=3), and transient paresthesia (n=1) occurredduring infusion of the magnesium bolus. No seriousadverse effects occurred.

DiscussionOur study reports results of the first randomized, pla-

cebo-controlled trial to investigate the antiarrhythmic ef-fect of acute parenteral magnesium administration onventricular arrhythmia in patients with symptomatic heartfailure. We found that magnesium infusion significantlyreduced total ventricular ectopy, couplets, and episodes ofventricular tachycardia by 53%, 76%, and 69%, respec-tively. The rate of the fastest episode of ventriculartachycardia was also significantly decreased during mag-nesium administration. Serum magnesium concentrationwas substantially increased over the entire infusion period.The infusion was well tolerated. Magnesium administra-tion produced no sustained effects on blood pressure orheart rate. A reduction in ventricular ectopy was observedeven though the preinfusion magnesium concentration onthe placebo day was higher than on the magnesium day,which could have diminished our ability to detect anantiarrhythmic effect of magnesium. Serum potassiumconcentration did not appear to change significantly dur-ing magnesium administration. Only rarely did ventriculararrhythmia frequency appear to increase during magne-sium infusion.

*-r

by guest on April 16, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

664 Circulation Vol 89, No 2 February 1994

Ventricular Ectopy During Magnesium Infusion Compared With Washout

Premature VentricularContractions per Hour Couplets per Hour

Time in Hours Magnesium Washout Magnesium Washout1-2 88±41 120±48 4±2 6±5

1-8 82±35 140±69 13±8 47±39

9-16 80±27 199±85* 12±7 54±33t

17-24 53±16 202±88t 7±4 48±26t

Results expressed as mean±SEM. n=16. P values based on comparison of magnesium and washout.*P<.05, tP<.01.

Previous WorkThere are limited data on the effect of magnesium on

ventricular arrhythmia in patients with congestive heartfailure. Dyckner and Wester4 infused 30 mmol magne-sium sulfate over 10 hours in 33 patients suspected ofbeing magnesium deficient, including 20 patients withcongestive heart failure. Ventricular ectopy was signifi-cantly reduced during 3 hours of monitoring conducted12 hours after magnesium administration. The effect ofmagnesium in the subjects with heart failure alone was

not reported. Camara et a15 administered intramuscularmagnesium to 3 patients hospitalized with heart failurecaused by Chagas' disease. Episodes of nonsustainedventricular tachycardia were abolished, and ventricularectopy was significantly reduced after magnesium ad-ministration. Frustaci et a16 reported that parenteralmagnesium administration abolished ventricular tachy-cardia and reduced ventricular extrasystoles by 80% in 3patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and in 1 patientwith right ventricular dysplasia, all of whom had lowmyocardial magnesium concentrations. There was no

effect in 4 patients who had myocarditis and normalmyocardial magnesium concentrations. Perticone et a17studied 10 patients with ischemic dilated cardiomyopa-thy and symptomatic ventricular tachycardia who hadnormal serum magnesium concentrations and were nottaking diuretics. Intravenous administration of magne-sium sulfate (6 g) daily for 1 week resulted in a

significant reduction in the frequency of PVCs andcouplets and abolished ventricular tachycardia by day 5.In contrast to the previous studies, Gottlieb et a18conducted a non-placebo-controlled trial in 30 patientswith symptomatic heart failure. They found no reduc-tion in ventricular arrhythmia during 6 hours of moni-toring after magnesium sulfate infusion (0.2 mEq/kgover 1 hour) compared with a similar baseline period 1week previously.Our study differs from this previous work in several

important respects. None of the prior investigationswere placebo-controlled studies. By contrast, our inves-tigation was randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled. All patients had well-documented chroniccongestive heart failure secondary to systolic dysfunc-tion and were receiving an angiotensin-converting en-zyme inhibitor and digoxin. None of the patients werereceiving other antiarrhythmic agents, calcium channelantagonists, or 3-blockers that could have influencedthe frequency of ventricular arrhythmia. The study wasdesigned with a sufficient sample size and monitoringperiod to have the power to detect an antiarrhythmic

effect of magnesium. Serum magnesium was also sub-stantially increased, approximately twofold, over theentire infusion period.Our data suggest that augmentation of serum magne-

sium concentration may result in an antiarrhythmiceffect, independent of repletion of body stores. Nocarryover effect of magnesium infusion on the fre-quency of ventricular arrhythmia was evident when theplacebo day followed the magnesium day. Furthermore,ventricular ectopy began to increase within severalhours after completion of the magnesium infusion. Thisgradual increase in ventricular ectopy during the wash-out day as serum magnesium concentration was de-creasing also suggests that the antiarrhythmic effect ofmagnesium may be dose related. A dose-response rela-tion may help to reconcile the results of Gottlieb et a18with our study. Our dosing regimen maintained a 100%increase in serum magnesium during monitoring com-pared with a 33% augmentation at the end of a 6-hourmonitoring period in their study.Two studies of oral magnesium supplementation have

been reported. Gottlieb et al13 reported no effect of 8weeks of oral magnesium chloride supplementation(128 mg TID as tolerated) compared with placebo onventricular arrhythmia in 40 patients with congestiveheart failure. Serum magnesium concentrations werenot significantly changed at the end of treatment. Incontrast, Bashir et al14 found that a substantially higherdose of magnesium chloride (15.78 mmol/d or =1500mg/d) significantly decreased ventricular ectopic activ-ity, including nonsustained ventricular tachycardia in 18patients with congestive heart failure on long-term loopdiuretic therapy. Serum magnesium concentration wasincreased by only 6%, but this was statistically signifi-cant. Serum potassium was also significantly increased,by 10%. These oral studies also support the concept thatthe antiarrhythmic effect of magnesium may be doserelated.

Antiarrhythmic MechanismsVentricular arrhythmias may arise in heart failure by

many mechanisms, including enhanced automaticityand triggered activity as well as reentry. Several basicand clinical studies suggest that magnesium may notaffect ventricular arrhythmia arising from reentrantmechanisms.15-'8 By contrast, several laboratory studiesindicate that magnesium may suppress ventricular ar-rhythmias secondary to enhanced automaticity or trig-gered activity.23"19 Clinically, torsades de pointes20 anddigitalis-induced ventricular arrhythmias21 have been

by guest on April 16, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

Sueta et al Magnesium and Ventricular Arrhythmia in Heart Failure 665

successfully treated with parenteral magnesium, regard-less of the serum magnesium concentration.The precise role of magnesium depletion in the

generation of ventricular arrhythmia in patients withheart failure remains unresolved. Hypomagnesemia hasbeen reported in 19% to 37% of patients with heartfailure.22-24 However, evaluation of magnesium status inpatients with heart failure is problematic. A normalrange has not been well defined, and only 1% ofmagnesium is in the serum. There have been conflictingreports about the relation between serum magnesiumconcentration and frequency of ventricular arrhythmiaand prognosis in patients with heart failure.23'24 Only afew investigators have studied the relation betweenventricular arrhythmia and myocardial magnesium con-centration. Ralston et a125,26 found that myocardialmagnesium concentration did not correlate with serum,lymphocyte, or skeletal muscle concentrations in 23patients with NYHA class II through IV congestiveheart failure. There was no significant difference inmyocardial magnesium concentration between the 9patients with a history of sustained ventricular tachy-cardia and the 14 patients without a history of ventric-ular arrhythmia. In contrast, Frustaci et a16 found thatmagnesium infusion significantly reduced ventriculararrhythmia only in the 4 patients in the study withreduced myocardial magnesium concentration.Magnesium has a number of other physiological

effects that could contribute to its antiarrhythmic effect.Magnesium has important effects on potassium homeo-stasis,27 coronary tone,28 ventricular afterload,29 andcatecholamine release.30 Further investigation will benecessary to determine the contribution, if any, of theseeffects to the antiarrhythmic action of magnesium weobserved.

Study LimitationsCertain limitations of the present study should be

considered as the results are interpreted. Our clinicaltrial examined the acute antiarrhythmic effect of paren-teral administration of magnesium chloride. Whethersimilar beneficial effects on ventricular arrhythmiawould occur during chronic oral administration of mag-nesium independent of an effect on serum potassium isunknown. Our study also was not designed to assess theimpact of magnesium administration on symptomaticventricular arrhythmia or on the frequency of suddendeath in patients with congestive heart failure. Addi-tional studies of larger numbers of patients will berequired to resolve these important issues.

ConclusionsOur study demonstrated that acute parenteral admin-

istration of magnesium chloride, in a dose that aug-ments the serum concentration twofold, results in asignificant reduction in ventricular arrhythmia in pa-tients with symptomatic heart failure. Our results sug-gest that further investigation of the dose-responserelation and the effect of chronic oral magnesiumadministration on ventricular arrhythmia in a largerpopulation of patients with congestive heart failure iswarranted.

AcknowledgmentsThis study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid from

the American Heart Association, North Carolina Affiliate,Inc, and Public Health Service research grant MO1-RR00046 from the General Clinical Research Centersbranch of the Division of Research Resources. We wish tothank Laura Shrewsbury for her technical assistance in thepreparation of the manuscript.

References1. Dyckner T, Wester PO. Magnesium deficiency in congestive heart

failure. Acta Pharmacol ToxicoL 1984;54(suppl 1):119-123.2. Bailie DS, Inoue H, Kaseda S, Ben-David J, Zipes DP. Magnesium

suppression of early afterdepolarizations and ventricular tachyar-rhythmias induced by cesium in dogs. Circulation. 1988;77:1395-1402.

3. Kaseda S, Gilmour RF, Zipes DP. Depressant effect of magnesiumon early afterdepolarizations and triggered activity induced bycesium, quinidine, and 4-aminopyridine in canine cardiac Purkinjefibers. Am Heart J. 1989;118:458-466.

4. Dyckner T, Wester PO. Ventricular extrasystoles and intracellularelectrolytes before and after potassium and magnesium infusionsin patients on diuretic treatment. Am Heart J. 1979;97:12-18.

5. Camara EJN, Cruz TRP, Nassri JM, Rodrigues LEA. Musclemagnesium content and cardiac arrhythmias during treatment ofcongestive heart failure due to chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy.Braz J Med Biol Res. 1986;19:49-58.

6. Frustaci A, Caldarulo M, Schiavoni G, Bellocci F, Manzoli U,Cittadini A. Myocardial magnesium content, histology, and anti-arrhythmic response to magnesium infusion. Lancet. 1987;2:1019.

7. Perticone F, Borelli D, Ceravolo R, Mattioli PL. Antiarrhythmicshort-term protective magnesium treatment in ischemic dilatedcardiomyopathy. JAm Coll Nutr. 1990;9:492-499.

8. Gottlieb SS, Fisher ML, Weinberg M, Greenberg N. Does intra-venous magnesium sulfate decrease arrhythmia frequency in CHF.Circulation. 1991;84(suppl):II-59. Abstract.

9. Mungall DR, ed. Applied Clinical Pharmacokinetics. New York,NY: Raven Press; 1983:356.

10. Archer WH, Emerson RL, Reusch CS. Intra and extracellular fluidmagnesium by atomic spectrophotometry. Clin Biochem. 1972;5:159-161.

11. Koch GG, Stokes ME. Chi-square tests: numerical examples. In:Johnson NL, Kotz S, eds. Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences 1. NewYork, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1982:457-472.

12. CAPS Investigators. The cardiac arrhythmia pilot study. Am JCardiol. 1986;57:91-95.

13. Gottlieb SS, Fisher ML, Krichten C, Patten RD, Pressel M,Brackett J. Is oral magnesium replacement antiarrhythmic inpatients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21:336A. Abstract.

14. Bashir Y, Sneddon JF, Staunton A, Haywood GA, Simpson IA,Camm AJ. Effects of magnesium chloride replacement in chronicheart failure: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Circulation.1991;84(suppl II):II-58. Abstract.

15. DiCarlo LA Jr, Morady F, DeBuitleir M, Krol RB, Schurig L,Annesley TM. Effects of magnesium sulfate on cardiac conductionand refractoriness in humans. JAm Coll Cardiol. 1986;7:1356-1362.

16. Kulick DL, Hong R, Ryzen E, Rude RK, Rubin JN, Elkayam U,Rahimtoola SH, Bhandari AK. Electrophysiologic effects of intra-venous magnesium in patients with normal conduction systems andno clinical evidence of significant cardiac disease. Am Heart J.1988;115:367-373.

17. Brooks R, McGovern BA, Brussel T, Chernow B, Laramee B,Garan H, Ruskin JN. Limited effectiveness of magnesium infusionsfor suppressing inducible sustained monomorphic ventriculartachycardia. Circulation. 1989;80(suppl II):II-659. Abstract.

18. Hilton TC, Fredman C, Holt DJ, Bjerregaard P, Ira GH, JanosikDL. Electrophysiologic and antiarrhythmic effects of magnesium inpatients with inducible ventricular tachyarrhythmia. Clin Cardiol.1992;15:176-180.

19. Ghani MF, Rabah M. Effect of magnesium chloride on electricalstability of the heart. Am Heart J. 1977;94:600-602.

20. Tzivoni D, Banai S, Schuger C, Benhorin J, Keren A, Gottlieb S,Stern S. Treatment of torsades de pointes with magnesium sulfate.Circulation. 1988;77:392-397.

21. Cohen L, Kitzes R. Magnesium sulfate and digitalis-toxicarrhythmias. JAMA. 1983;249:2808-2810.

by guest on April 16, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

666 Circulation Vol 89, No 2 February 1994

22. Wester PO, Dyckner T. Intracellular electrolytes in cardiac failure.Acta Med Scand. 1986;707(suppl):33-36.

23. Gottlieb SS, Baruch L, Kukin ML, Bernstein JL, Fisher ML,Packer M. Prognostic importance of the serum magnesium con-centration in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am CollCardiol. 1990;16:827-831.

24. Eichhorn EJ, Tandon PK, DiBianco R, Timmis GC, Fenster PE,Shannon J, Packer M. Clinical and prognostic significance of serummagnesium concentration in patients with severe chronic con-gestive heart failure: the PROMISE study. J Am Coll Cardiol.1993;21:634-640.

25. Ralston MA, Murnane MR, Kelley RE, Altschuld RA, UnverferthDV, Leier CV. Magnesium content of serum, circulating mono-nuclear cells, skeletal muscle, and myocardium in congestive heartfailure. Circulation. 1989;80:573-580.

26. Ralston MA, Murnane MR, Unverferth DV, Leier CV. Serum andtissue magnesium concentrations in patients with heart failure andserious ventricular arrhythmias.Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:841-846.

27. Solomon R. The relationship between disorders of K' and Mg+homeostasis. Semin Nephrol. 1987;7:253-262.

28. Kimura T, Hirofumi Y, Sakaino N, Rokutanda M, Jougasaki M,Araki H. Effects of magnesium on the tone of isolated humancoronary arteries: comparison with diltiazem and nitroglycerin.Circulation. 1989;79:1118-1124.

29. Rasmussen HS, Larsen OG, Meier K, Larsen J. Hemodynamiceffects of intravenously administered magnesium on patients withischemic heart disease. Clin Cardiol. 1988;11:824-828.

30. James MF, Beer RE, Esser JD. Intravenous magnesium sulfateinhibits catecholamine release associated with tracheal intubation.Anesth Analg. 1989;68:772-776.

by guest on April 16, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

Adams, JrC A Sueta, S W Clarke, S H Dunlap, L Jensen, M B Blauwet, G Koch, J H Patterson and K F

patients with heart failure.Effect of acute magnesium administration on the frequency of ventricular arrhythmia in

Print ISSN: 0009-7322. Online ISSN: 1524-4539 Copyright © 1994 American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved.

is published by the American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231Circulation doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.89.2.660

1994;89:660-666Circulation.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/89/2/660World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the

http://circ.ahajournals.org//subscriptions/

is online at: Circulation Information about subscribing to Subscriptions:

http://www.lww.com/reprints Information about reprints can be found online at: Reprints:

document. Permissions and Rights Question and Answer this process is available in the

click Request Permissions in the middle column of the Web page under Services. Further information aboutOffice. Once the online version of the published article for which permission is being requested is located,

can be obtained via RightsLink, a service of the Copyright Clearance Center, not the EditorialCirculationin Requests for permissions to reproduce figures, tables, or portions of articles originally publishedPermissions:

by guest on April 16, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from