ACTBAS 1 Downloaded Lecture Notes

-

Upload

regine-chua -

Category

Documents

-

view

83 -

download

12

description

Transcript of ACTBAS 1 Downloaded Lecture Notes

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 1of A

Unit I

Introduction

Overview

Background The evolution of accounting is attributed to the social and economic needs of

society. As business and society become more complex, accounting develops

new concepts, methods and techniques to meet the ever changing and

increasing needs for financial information. Without the necessary information

furnished by accounting, many complex social programs and economic

development may never have been realized.

Information, in any market economy, assists decision-makers in making wise

choices regarding the use of limited resources under their control. When

decision-makers are able to make well-informed decisions, resources are

allocated in a manner that better meets the needs and goals of companies

within the given market.

The Philippines, being a developing country, would need a great deal of

reliable and timely information to compete in the global market and

accounting will play an important role in this prevailing competitive global

structure of the economy. Companies use accounting information to evaluate

the business situations around the world. It is therefore necessary that future

accountants, businessmen, entrepreneurs and economists must be trained

properly on how to generate and interpret this financial information.

Purpose The purpose of Unit I “Introduction to Accounting and Basic Accounting

Principles” is to provide students with brief descriptions of the nature and

scope of accounting. This unit also includes simple explanation of the 13

basic accounting concepts.

In this unit This unit contains the following topics:

Topics See Page

Nature and Scope of Accounting 2 of A

History of Accounting Thought 5 of A

Users of Financial Statements 6 of A

Forms of Business Organizations 8 of A

Basic Accounting Concepts 9 of A

The Accounting Profession 17 of A

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 2of A

Nature and Scope of Accounting

Overview The two terms accounting and bookkeeping have been used interchangeably

and without distinction. This line of thought finds support based on the

condition prevailing during the early times when businesses were not as

complex and multifarious as they are nowadays. However, recognition of the

importance of accounting in the development of modern business methods,

the industrial revolution and the growth of unlimited companies that provided

the impetus for the development of accounting as a profession has led to the

distinction in the concepts and effects of bookkeeping as against accounting.

Definition The following definitions differentiates bookkeeping from accounting:

• Bookkeeping deals primarily with the systematic method of recording and

classifying financial transaction of business. It is considered to be the

procedural element of accounting as arithmetic is a procedural element of

mathematics. Normally, books are set up and prepared in a manner that

ensures an orderly recording and classification of business transactions.

However, because of the rapid economic growth and technological changes,

which necessitate the mechanization of the bookkeeping job, the demand

for bookkeepers has been reduced. The bookkeeping process is now

basically done through the use of computers and soft wares designed for

such purpose.

• Accounting as differentiated from bookkeeping has been authoritatively

defined by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA),

as the art of recording, classifying and summarizing in a significant manner

and in terms of money, transactions and events that are, in part at least, of a

financial character, and interpreting the results thereof. Accounting is also

defined by the Philippine Institute of Certified Public Accountants (PICPA)

as a system that measures business activities, processes given information

into reports, and communicates those findings to decision-makers.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 3of A

Nature and Scope of Accounting, Continued

Definition,

con’t The “art” in AICPA’s definition connotes that accounting is an art of

communication. Although the primary function of accounting is to supply of

financial information, it also provides non-financial information.

Moreover, accounting is referred to as a science in the sense that is a

systematized knowledge. A growing body of accounting theories seeks to

place accounting in the context of human knowledge and activity in general.

Hence, an accountant is a bookkeeper and more, for he must not only be well-

versed with the recording process but must also be concerned with the

functions of interpretation and analysis of financial statements which require

the exercise of reason, judgment and intelligence of a higher order. It is these

functions that best distinguish accounting from bookkeeping.

Language of

Business Accounting is a special kind of language. It is often described as the

“language of business” because it is the medium of communication between

a business firm and the various parties interested in its financial activities. It is

the tool, which enables firms to communicate to various interested third

parties certain quantitative information about the financial activities of a

business.

Accounting is often utilized whenever there are business transactions. And

business transactions normally involve people. One cannot engage in business

without involving and affecting other persons. The activities of a business

enterprise involve and affect many parties -- management, owners, short-term

and long-term creditors, employees, prospective investors, the government,

and even the general public. All these interested parties need to be informed

about the financial affairs of a business enterprise. Accounting, therefore,

serves this need of providing quantitative information, primarily financial in

nature, about economic entities that is useful in making economic decisions.

The principal accounting reports are the financial statements, i.e., the balance

sheet, income statement and the cash flow statement. As the major end

products of accounting, these statements convey to management and/or

interested outsider(s) the messages about the financial activities of the

business.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 4of A

Nature and Scope of Accounting, Continued

Language of

Business, con’t. Information needed by different parties is of three kinds:

• The financial condition or position of the business, i.e., the amounts and

kinds of its assets and liabilities, and the status of the owners’ interest at a

given point in time.

• The financial performance or results of operations, i.e., whether the

business operating activities during a given period of time resulted in net

income or a loss.

• The financing and investing activities that are responsible for the changes in

the financial resources of the business, i.e., the sources and applications of

fund during a given period of time.

This information, furnished through accounting, are utilized by end-users as

basis for reaching important decisions affecting themselves, the business

enterprise, the government and other parties.

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 5of A

History of Accounting Thought

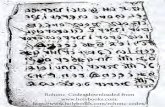

Overview Accounting has a long history. Some scholars claim that writing arose in

order to record accounting information. Account records date back to the

ancient civilizations of China, Babylonia, Greece and Egypt. The rulers of

these civilizations used accounting to keep track of the cost of labor and

materials used in building structures like the great pyramids.

History Accounting developed as a result of the information needs of merchants in the

city-states of Italy during the 1400s. In that commercial climate a monk, Luca

Pacioli, a mathematician and friend of Leonardo da Vinci, published the first

known description of double-entry bookkeeping entitled Summa de

Arithmetica, Geometria, Proportioni et Proportionalite (Everything about

Arithmetic, Geometry, and Proportion), published in Venice in November

1494. This book contained primarily principles of mathematics and

incidentally set of accounting procedures. (Horngren, Harison and

Robinson,1995).

The pace of accounting development increased during the Industrial

Revolution as the economics of developed countries began to mass-produce

goods. Until that time, merchandise was priced based on managers’ hunches

about cost but increased competition required merchants to adopt more

sophisticated accounting system.

In the nineteenth century, the growth of corporations, especially those in the

railroad and steel industries, spurred the development of accounting.

Corporate owners, were no longer necessarily the managers of their business.

Managers had to create accounting systems to report to the owners how well

their businesses were doing.

Government played a role in leading more development in the field of

accounting when it started using the income tax. Accounting supplied the

concept of “income”. Also, government at all levels has assumed expanded

roles in health, education, labor and economics planning. To ensure that the

information that it uses to make decisions is reliable, the government has

required strict accountability in the business community.

At the beginning of the third millenium, there would still be a lot of

developments in the field of accounting. The great challenge of globalization

and the effects of new technologies (e.g. super computers, robotics, inter and

intra-net, etc.) pose a shift in the structure and pattern in this field. More and

better information are now being required and therefore, accounting, being the

means used in communicating business and financial information must also

evolve into a more efficient level.

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 6of A

Users of Financial Statements

Overview Today's accountant focuses on the ultimate needs of decision-makers who use

accounting information, whether decision makers are inside or outside the

business. Accounting "is not an end in itself," but is an information system

that measures, processes, and communicates financial information about an

identifiable economic entity (Needles, Belverd, et al, 1999). It provides a

vital service by supplying the information decision-makers needs to make

"reasoned choices among alternative uses of scarce resources in the conduct

of business and economic activities.”

Internal Users Those who are directly involved in the business enterprise such as:

• Owners. The owner provides the money/capital that the business needs to

begin operations. Through the financial reports, the owner can properly

manage and monitor the business, analyzing whether or not he can expect

reasonable return from his investment.

• Management. Managers of business use accounting information to set

goals for the organization, to evaluate the progress made toward those goals,

and to take corrective action if necessary.

External Users Those who are not directly involved in the operation of the business such as:

• Potential investors. Investors use financial reports in evaluating what

income they can reasonably expect from their investment.

• Creditors. Potential lenders or current creditors determine the borrower’s

ability to meet scheduled payments.

• Taxing authorities. Local and national government levy taxes on

individuals and businesses. The amount of the tax is determined using

accounting information.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 7of A

Users of Financial Statements, Continued

External Users,

con’t. Those who are not directly involved in the operation of the business such as:

• Government regulation agencies. Most organizations face government

regulation. For example, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

requires businesses to disclose certain financial information to the public.

The SEC, like many government agencies, bases its regulatory activity in

part on the accounting information it receives from firms.

• Nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit organizations, e.g., churches, most

hospitals, government agencies, and colleges, which operates for purposes

other than to earn a profit use accounting information in much the same way

that profit-oriented businesses do.

• Other users. Employees and labor unions may make wage demands based

on the accounting information that shows their employer’s reported income.

Consumer groups and the general public may also be interested in the

amount of income that the businesses earned.

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 8of A

Forms of Business Organization

Based on

Ownership There are three basic forms of business organization according to

ownership. This classification is based on owner/s investing or putting capital

on a business being started.

• Sole or single proprietorship. When only one person makes the

investment.

• Partnership. When two or more persons agree to operate the business as

co-owners under certain conditions. The persons owning this form of

business are called partners.

• Corporation. A body formed and authorized by law to act as a single

person although constituted by one or more persons and legally endowed

with various rights and duties. This is the more popular form of business

organization today. Persons who put in capital in a corporation are called

stockholders.

Based on

Operations or

Activity

Business may also be classified according to business operations or activity

after the necessary capital has been received from the owner or owners and

the business starts its operations. The purpose for which the business has

been formed will determine the nature of its activities.

• Service concern. Businesses engage in the rendering of services to others

for a fee, like the beauty parlor, law firm, dental clinic, and medical clinic.

• Merchandising or trading concern. Businesses that are into the buying

and selling of goods or commodities like the grocery store, drug store and

department store.

• Manufacturing concern. Businesses that are engaged in the processing of

products or the conversion of raw materials into finished goods that are then

sold like the furniture factory and shoe factory. A trading or merchandising

business differs from a manufacturing concern in that the former buys

finished goods, which are ready for sale, while the latter produces or

manufactured the goods that it sells.

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 9of A

Basic Accounting Concepts

Overview The Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), also known, as

the basic accounting concepts are the ground rules that govern how

accountants measure, process and communicate financial information. These

principles have been developed by the accounting profession over the years to

provide a consistent system of financial reporting in a constantly changing

business environment (Smith, Keith, et al, 1993).

These concepts assure users of financial statements that the reports are

prepared in specific ways so that they are reliable and comparable for the

usefulness of these reports rests on their reliability and comparability.

Purpose Generally accepted accounting principles serve three basic purposes:

• They help increase the confidence of financial statement users that the

financial statements are representationally faithful.

• They provide companies and accountants who prepare financial statements

with guidance on how to account for and report economic activities.

• And they provide independent auditors of financial statements with basis for

evaluating the fairness and completeness of those statements (Chasteen, l.,

Flaherty, R., O'Connor, M., 1998).

Entity Concept For accounting purposes, an entity is the organizational unit for which

accounting records are maintained, e.g., Joseph Labrador Accounting Firm.

Under entity concept, the business is regarded as having a separate and

distinct personality from that of the owner/s – generating its own revenue,

incurring its own expenses, owning its own assets, and owing its own

liabilities (Smith, Keith, et al, 1993). This means that the personal

transactions of owners must not be combined with transactions of the

business.

This concept also requires that an accountant record only those financial

activities that occur between the entity being accounted for and other parties.

Thus, the accounting entity assumption establishes boundaries or limits as to

what information should be included in the financial statements of a given

company.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 10of A

Basic Accounting Concepts, Continued

Entity Concept,

con’t Business Transaction. A business event that can be measured in terms of

money that affects the enterprise. This would give rise to an exchange

between the business and another party: “value received and value parted

with”.

Example: A barber provides services to a customer by trimming the latter's

hair: “value parted with” by the barber will be his service and time; and the

“value received” is the payment made by the client.

Monetary

Concept Money is a common unit of measure that we can use to record economic

transactions and prepare financial statements. Under this concept, money is

used as the unit of measure in preparing the various financial reports of the

company (example of these would be in terms of Peso ( P ), Dollar ( $ ), etc.).

It is a common belief that everybody understands money—it's universally

available, its certainly relevant to financial transactions and its easy to use.

But money, the "peso" in our case, as a measure of economic activity does not

have a constant value especially in recent years. It is not time in itself that

causes the change in the value of money but economic events, e.g., change in

government leadership, chaos in the stocks markets, etc. The stable money

concept assumes that, monetary unit of measure does not change value

overtime, even if in fact it does. The assumption is made in order to ensure

objectivity in reporting data on the financial statements.

Time Period

Concept It is also known as periodicity concept. It divides the life of the business into

regular intervals (usually one year) at the end of which financial statements

are prepared. This means that the economic activities undertaken during the

life of an accounting entity are assumed to be divisible into various artificial

time periods for financial reporting purposes. For example, it is assumed that

a reasonable report of income earned can be made annually or quarterly, even

though the revenue generating activities of a business are continuous.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 11of A

Basic Accounting Concepts, Continued

Time Period

Concept, con’t. This is the assumption that implies that it is necessary to measure accounting

income for periods of time less than the life of a firm and that measurement

will not be precise but will be timely and therefore useful (Smith, Keith, et al,

1993).

• In choosing one year, the business has two options:

• Calendar Year. A twelve-month period beginning with January 1 and

ending December 31.

• Fiscal Year. The length of the fiscal period is determined by the nature of

the business and the frequency of the need for data regarding the financial

condition and progress of the business. A yearly fiscal period does not

start with January 1 and end on December 31. (e.g., educational

institutions normally follows a fiscal year beginning May 1 and ending

April 30).

Revenue

Realization

Concept

Revenue or income is the inflow of assets that results from producing goods

or rendering services. Revenue is not earned all at one point in time. Instead,

the earning process extends over a considerable length of time.

The revenue realization concept provides that income is recognized when

earned regardless whether cash is received. This means that both of the

following conditions are met:

• The earning process is essentially complete;

• An exchange has taken place (Smith, Keith, et al, 1993).

These two conditions for most of the companies are met at the time goods are

sold or services rendered. To wit:

• Two points of income recognition:

• Income is considered earned when services are fully rendered.

• Income is considered earned when goods or merchandise are fully

delivered.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 12of A

Basic Accounting Concepts, Continued

Accrual

Concept This concept requires that income be recorded when earned regardless

whether cash is received. And an expense be recognized when incurred (e.g.,

when services or benefits have already been received) regardless whether

payment is made.

To apply the accrual concept, accountants have developed the accrual

accounting. The accrual method of accounting attempts to record the financial

effects on a company of transactions and other events and circumstances in

the periods in which those transactions, events, and circumstances occur

rather than only the periods in which cash is received or paid by the firm. This

means that accrual accounting consists of all techniques developed by

accountants to apply both the accrual and matching concepts (Needlers,

Powers, et al, 1999).

Throughout this study guide we illustrate the accrual basis of accounting,

which is required under the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles.

Essentially, the accrual basis records expenses (i.e., cost of items used or

consumed in business operations, e.g., electricity, water, supplies, etc.) when

incurred and revenues (i.e., price of goods sold or services rendered, e.g.,

service income, sales) when earned.

It is also worth mentioning here that other than the accrual basis, we also have

what we call the cash basis of accounting, which generally records a journal

entry upon exchange of cash, typically does not require many adjusting entries

(Dyckman, T., Dukes, Davis, C., 1998).

Matching

Concept This concept states that all expenses incurred to generate revenues must be

recorded in the same period that the income are recorded to properly

determine net income or net loss of the period. There is a cause-and-effect

relationship between revenue and expense recognition implicit in this

definition

Revenues are inflows of resources resulting from providing goods or services

to customers. For merchandising companies like Shoe Mart, the main source

of income is sales revenue derived from selling merchandise. Service firms

such as SGV and Company generate revenue by providing services.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 13of A

Basic Accounting Concepts, Continued

Matching

Concept, con’t Expenses on the other hand are outflows of resources incurred in generating

revenue. They represent the costs of providing goods and services. The

matching principle is a key player in the way we measure expenses. We

attempt to establish a causal relationship between revenues and expenses. If

causality can be determined, expenses are reported in the same period that the

revenue is recognized. If the causal relationship cannot be established, the

expense is either related to a particular period. Allocated over several periods,

or expensed as incurred (Spiceland, D., Sepe, J., 1998).

Example:

Revenues earned in June and collected in June P30,000

Revenues earned in June but collected in July 20,000

Revenues earned in May but collected only in June 10,000

Expenses incurred in June and paid in June 10,000

Expenses incurred in June but payable in July 15,000

Expenses incurred in May but paid in June 7,000

Net Income or Net loss is computed by deducting total expenses of the period

to total revenue of the same period. If total revenue is greater than total

expenses, the company’s result of business operation is a net income. But if

total expense is greater, the result is a net loss.

Net Income for June:

Revenues (30,000 + 20,000) P50,000

Expenses (10,000 + 15,000) 25,000

Net Income P25,000

======

Objectivity

Concept This principle requires that all transactions must be evidenced by business

documents free from personal biases and independent experts (e.g., CPA) can

verify reports.

Example: Official receipts, invoices, vouchers, etc.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 14of A

Basic Accounting Concepts, Continued

Cost Concept Assets, i.e., resources acquired by the business, must be recorded at

acquisition price (i.e., what you have to give up in exchange for an ownership

of an asset) and no adjustments are to be made on this valuation in later

periods.

The cost principle assumes that assets are acquired in business transactions

conducted at arm's length transactions, i.e., transactions between a buyer and

a seller at the fair value prevailing at the time of the transaction. For non

cash transactions conducted at arm's length, the cost principle assumes that

the market value of the resources given up in the transaction provides reliable

evidence for the valuation of the item acquired (Dyckman, T., Dukes, Davis,

C., 1998).

The cost principle provides guidance primarily at the initial acquisition date.

Once acquired, the original cost basis of some assets is then subjected to

depreciation, depletion, amortization, etc. over time to reflect the said assets

in the balance sheet in a more realistic valuation.

Going Concern

Concept In the absence of information to the contrary, this concept assumes that the

business is to continue its operations indefinitely. This means that the

business will stay in operation for a period of time sufficient to carry out

contemplated operations, contracts, and commitments. This non liquidation

assumption provides a conceptual basis for many of the classifications used in

accounting. Assets and liabilities, for example, are classified as either current

or long term on the basis of this assumption. If continuity is not assumed, the

distinction between current and long term loses its significance; all assets and

liabilities become current. Continuity supports the measurement and recording

of assets and liabilities at historical costs and not at their liquidation values

(i.e., estimated net realizable amounts) (Dyckman, t., Dukes, Davis, C.,

1998).

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 15of A

Basic Accounting Concepts, Continued

Conservatism

Concept This concept has a powerful influence in valuing assets and measuring net

income. When faced which uncertainties, the accountant traditionally leans

towards the direction of caution, choosing the method that would give the

business a less favorable financial condition and lowers net income.

The reasoning behind this assumption is that investors prefer information that

does not unnecessary raise expectations. For example:

• In recognizing assets, preferably the lower of two alternative valuations

would be recorded.

• In recognizing liabilities, preferably the higher of two alternative amounts

would be recorded.

• In recording revenues, expenses, gains, and losses where there is reasonable

doubt as to the appropriateness of alternative amounts, the one having the

least favorable effect on net income should be preferred.

Conservatism assumes that when uncertainty exists, the users of financial

statements are better served by understatement than by overstatement of net

income and assets (Dyckman, t., Dukes, Davis, C., 1998).

Consistency

Concept This concept states that once a method is adopted, it must not be changed

from year to year to allow comparability of financial statements between years

and between businesses.

For example if the First In First Out (FIFO) method was used by the firm in

valuing their inventories, the firm should not change the method into Last In

First Out (LIFO) in the following year and then go back again to FIFO on the

next year.

Consistency in this case means that the reported information conforms with

procedures that remain unchanged from period to period. Comparison

overtime are difficult unless there is consistency in the way accounting

principles are applied across accounting year.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 16of A

Basic Accounting Concepts, Continued

Materiality

concept This concept refers to relative importance of an item or event. An item/event

is considered material if knowledge of it would influence the decision of

prudent users of financial statements.

To illustrate an instance where strict conformity with GAAP is not necessary

because an item is immaterial, consider a low-cost asset, such as a P150 waste

can. This item can be recorded as an expense in full when purchased rather

than an asset subject to depreciation. The peso amount involved is simply too

small for external users of financial reports to worry about.

Disclosure

concept All relevant and material events affecting the financial condition/position of a

business and the results of its operations must be communicated to users of

financial statements.

We must remember that the purpose of accounting is to provide information

that is useful to decision-makers. So, naturally, if there is accounting

information not included in the primary financial statements that would

benefit users, that information should be provided to.

Supplemental information is disclosed in a variety of ways including:

• Parenthetical comments or modifying comments placed on the face of the

financial statements.

• Disclosure notes conveying additional insights about company operations,

accounting principles, contractual agreements, and pending litigation.

• Supplemental financial statements that report more detailed information

than is shown in the primary financial statements. (Spiceland, D., Sepe, J.,

1998)

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 17of A

The Accounting Profession

Overview The success of the accountant in the accounting profession depends on how

well he understands the accounting procedures and principles, and on how

clearly and accurately he can communicate financial information to the users

of the statements.

Classification The nature of these works though relies on the position, which the accountant

holds in his field. The positions in the field of accounting are generally

classified into two, namely, public accounting and private accounting.

• Public Accountants are those who serve the general public and collect

professional fees for their work such as doctors and lawyers do. Their work

include auditing, income tax planning and preparation and management

consulting. Those public accountants who have certain professional

requirements are designated as Certified Public Accountants (CPAs).

• Private Accountants work for a single business, e.g. PLDT, Meralco,

Jollibee, etc. Charitable organizations, educational institutions and

government employ private accountants. Some accountants would also

pursue a career in education and research

Certified Public

Accountant A Certified Public Accountant (CPA) is a professional accountant who earns

his title through a combination of education, qualifying experience, and an

acceptance score in the written national examination given by the Board of

Accountancy.

The Board of Accountancy prepares, grades and gives the results of the

examination to the Professional Regulation Commission (PRC) who then

issues licenses that allow qualifying examinees to practice accounting as

CPAs.

CPAs must also be of good moral character and must carry on their

professional practices according to a code of professional conduct.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 18of A

The Accounting Profession, Continued

Organizations The Philippine Institute of Certified Public Accountants (PICPA) is the

national professional organization of CPAs in the country.

In order to formalize the accounting standard-setting function in the

Philippines, the Philippine Institute of Certified Public Accountants (PICPA)

established the Accounting Standards Council (ASC).

The Accounting Standards Council's main function is to establish and

improve accounting standards that will be generally accepted in the

Philippines (Preface to Statements of Financial Accounting Standards of

ASC, 1999).

The Accounting Standards Council (ASC) is the same body that formulates

the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). These principles are

the most important accounting guidelines that provide the general framework

determining what information is included in financial statements and how this

information is to be presented.

The ASC has approved in November 2004 the adoption of International

Accounting Standards (IAS) 1, Presentation of Financial Statements, issued

by the International Accounting Standards Boars (IASB), as the Philippine

Financial Reporting Standards(Preface to Philippine Accounting Standard

(PAS) 1 of ASC, 2005).

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 1 of B

Unit II

Balance Sheet

Overview

Background As a means of telling interested people about business operations, accounting

performs important tasks of recording daily transactions, classifying recorded

data, summarizing recorded and classified data and interpreting the

summarized facts. In all business enterprises, accounting information is

summarized in at least two basic financial reports.

One of these financial reports shows what the business is worth in terms of

the properties it owns (i.e., the assets), the debts it owes (i.e., the liabilities),

and the investment of its owner/s (i.e., the proprietorship). This report is

called the balance sheet and this statement informs the users of the financial

condition of the business at a given date, usually at the end of an accounting

period.

Purpose The purpose of Unit II “The Balance Sheet - Assets, Liabilities and Owner’s

Equity (Service Business)” is to illustrate different forms of balance sheet and

how to prepare them. Students will also be introduced in analyzing business

transactions using the accounting equation.

In this unit This unit contains the following topics:

Topics See Page

Forms of Balance Sheet 2 of B

Parts of the Balance Sheet 5 of B

Accounting Equation 7 of B

Current Assets 8 of B

Plant, Property and Equipment 10 of B

Current Liabilities 12 of B

Long-Term Liabilities 13 of B

Owner’s Equity 14 of B

Debit and Credit of Balance Sheet Items 15 of B

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 2 of B

Forms of Balance Sheet

Overview As provided in the revised Philippine Accounting Standard (PAS) 1 based on

the International Accounting Standards (IAS), the balance sheet should be

prepared following the new accounting concept of materiality and

aggregation, i.e., a separate schedule would be attached to the report to

explain the amounts with corresponding "notes". It is also required that a

separate statement of changes in equity be prepared, and therefore, the owner's

equity section of the balance sheet would show only the ending balance of the

capital account as shown in the given illustration.

The following discussions will provide readers information on how the

account and report format of balance sheets may be prepared.

Account Form In the account form of balance sheet, the assets are listed on the left side of

the report and the liabilities and proprietorship on the right side. The example

below illustrate the account form:

JOSEPH LABRADOR, COMPANY Balance Sheet

December 31, 20XI

ASSETS LIABILITIES AND OWNER'S EQUITY

Current Assets Current Liabilities

Cash & cash equivalents (7) P 20,000 Trade & Other Payables (11) P 55,000 Investments in trading securities 10,000 Current Portion of

Trade & Trade Receivables (8) 30,000 mortgage Payable 20,000

Prepaid Expenses (9) 29,000

Total Current Assets P 89,000 Total Current Liabilities P 75,000

Non Current Assets Non Current Liabilities

Property, Plant & Equip (10) 791,000 Notes Payable

(due in 3 years) P 70,000

Mortgage payable 180,000

Total non current liabilities 250,000

Total liabilities P 325,000

Owner's Equity

Labrador, Capital 555,000

TOTAL LIABILITIES

TOTAL ASSETS P880,000 AND OWNER'S EQUITY P 880,000 ======= =======

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 3 of B

Forms of Balance Sheet, Continued

Report Form A balance sheet prepared in report form shows the assets on the top section of

the statement and the liabilities and owner’s equity on the bottom section. The

example below illustrate the report form:

JOSEPH LABRADOR, COMPANY Balance Sheet

December 31, 20X1

A S S E T S

Current Assets Notes Cash & cash equivalents (7) P 20,000

Investments in Trading Securities 10,000

Trade & Other Receivables (8) 30,000

Prepaid Expenses (9) 29,000

Total Current Assets P 89,000

Non Current Assets Property, plant & equipment (10) 791,000

TOTAL ASSETS P 880,000

=======

LIABILITIES AND OWNER'S EQUITY

Current Liabilities Trade & other payables (11) P 55,000

Current portion of mortgage payable 20,000

Total Current Liabilities P 75,000

Non Current Liabilities Notes Payable (due in 3 years) P 70,000

Mortgage Payable 180,000

Total No Current Liabilities 250,000

Total Liabilities P 325,000

Owner’s Equity

Joseph, Capital 555,000

TOTAL LIABILITIES AND OWNER'S EQUITY P 880,000

=======

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 4 of B

Forms of Balance Sheet, Continued

Notes Note 7 - Cash & cash equivalents

Cash on Hand P 5,000

Cash in Bank 15,000

Total cash and cash equivalents P 20,000

======

Note 8 – Trade & other receivables

Accounts Receivable P 20,000

Less: Allowance for Doubtful Accounts 1,200 P 18,800

Notes Receivable 7,500

Interest Receivable 700

Advances to Employees 3,000

Total trade & other receivables P 30,000

=====

Note 9 – Prepaid expenses

Office Supplies on Hand P 6,000

Prepaid Insurance 20,000

Prepaid Advertising 3,000

Total Prepaid expenses P 29,000

=====

Note 10 – Property, plant & equipment

Land 300,000

Building 450,000

Less: Accumulated Depreciation 70,000 380,000

Office Equipment 110,000

Less: Accumulated Depreciation 20,000 90,000

Furniture & Fixtures 25,000

Less: Accumulated Depreciation 4,000 21,000

Total Carrying value 791,000

=====

Note 11 – Trade & other payables

Accounts Payable 20,000

Notes Payable 18,000

Interest Payable 2,000

Accrued Salaries Expense 5,000

Unearned Rent Income 10,000

Total trade & other payables 55,000

=====

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 5 of B

Parts of the Balance Sheet

Overview This portion will enumerate the different parts of a balance sheet and their

corresponding placement in the financial report being prepared.

Statement

Heading Includes the name of the business, tells the kind of statement it is, and gives

the date for which the report is prepared

Asset, Liability,

Proprietorship Items are grouped and each group of items is identified by special captions.

Captions Classification of each group of items appear against the left margin of the

statement.

Account titles Individual account titles in each classification are indented.

Current Assets The individual current assets are usually listed in order of their liquidity, with

the most liquid asset, “Cash” appearing first.

Plant,

Property,

Equipment

The plant assets are often listed in order of their expected useful life with the

assets with the longest expected useful life, “Land” appearing first.

Note (#) The separate schedule attached to the report explaining in detail the

aggregated amount presented on the face of the financial statement.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 6 of B

Parts of the Balance Sheet, Continued

Current

Liabilities The current liabilities are in theory listed in order of due date, with the debt

with the earliest due date appearing first.

Captions

Indicating

Totals

Each group of items (i.e., total current assets, total plant, property and

equipment, total current liabilities, etc.) is indented further.

Single Rule

Line The last figure in each group of items is underlined.

Final Totals The two final totals (i.e., total assets and total liabilities and owner’s equity)

appear as the last line in their respective sections and are underlined twice

(double ruled) to indicate a final total.

Peso Sign Peso signs are used (a) to the left of the first amount of a group of amounts

being combined and (b) to the left of each final total.

Peso Amount The peso amount for the detailed items is shown in one column; the total of

each classification is extended into the last column on the right-hand side of

the statement.

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 7 of B

Accounting Equation

Overview One important feature of the balance sheet relates to a very simple fact. The

balance sheet of any business must show total assets exactly equal in amount

to the sum of the liabilities and the capital. This relationship exists regardless

of the size of the enterprise or the variety of its assets, liabilities and

ownership interest. This identity is called the basic accounting equation.

Often it is stated as:

ASSETS = LIABILITIES + OWNER’S EQUITY

Which means, assets equal liabilities plus proprietorship. Other times the

equation appears as:

ASSET - L IABILITIES = OWNER’S EQUITY

or

ASSET - OWNER’S EQUITY = L IABILITIES

Assets This includes anything owned or possessed by the business which is capable

of being expressed in terms of money or possessing monetary values, and

which, consequently, is available for the payment of the debt of the business.

In short, assets represent the resources of the business.

Liabilities Economic obligations (i.e., debts) payable to an individual or an organization

outside the business.

Owner’s Equity The claim of an owner of a business over the assets of the business after the

claims of the creditors have been satisfied.

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 8 of B

Current Assets

Overview This includes cash and any other assets that are reasonably expected to be

converted into cash or consumed during one year or one operating cycle, i.e.,

whichever is longer.

Cash Currency, coins and checks that the business has received from customers and

other sources that have not yet been deposited in its bank account, as well as

the amount the business has on deposit in its bank account, against which

checks may be drawn in payment of bills.

Investments in

Trading

Securities

Short-term investment in stocks of other business (also known as marketable

securities).

Notes

Receivable The amount due in the near future from persons or companies on the basis of

their formal, written promises to pay cash to the business on the date specified

in the promissory note.

Interest

Receivable The amount of interest due as of the balance sheet date on notes received from

customers.

Accounts

Receivable The total amount owed to the business by charge account customers.

Advances to

employees Cash advance given to an employee to be liquidated in the form of service.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 9 of B

Current Assets, Continued

Merchandise

inventory The purchase price of the particular line of goods the business expects to sell

to its customers for cash or on a charge account basis. This represents goods

on hand as of the balance sheet date.

Accrued

Income Income already earned but not yet collected, such as interest earned on

promissory note issued by the customer before the maturity date of the note.

Supplies on

hand The cost value of such things as wrapping paper and packaging tape and

twine, (Store Supplies on Hand), computer ribbons, envelopes, stamps, paper

(Office Supplies on Hand) , and other assets of a similar nature that the

business will use up in performing its activities.

Prepaid

insurance That part of the premium cost of all kinds of insurance carried by the business

after the balance sheet date. Prepaid insurance is always classified as a

current assets even if the amount of the unexpired premiums cover a period

longer than one year, the time limit used in defining current assets.

Prepaid rent Rent paid by the business for facilities to be used after the balance sheet date.

For example, on December 1, 20X1, a business paid P30,000 for December,

January, and February rent. On a balance sheet dated December 31, 20X1, the

amount of Prepaid Rent would be shown as P20,000 the amount paid for the

use of the facilities for January and February, 20X2.

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 10 of B

Plant, Property and Equipment

Overview Assets are classified as plant, property and equipment if they meet the

following criteria: (1) they must have physical existence; (2) they must be

more or less permanent in nature; (3) they must not be for sale; (4) they must

be used in business operations; and (5) they must undergo depreciation

(except land). (Pefianco, E., Mercado,R., 1983)

Land The cost of land the business uses to carry on its activities - the lot on which

its factory or office building stands.

Building The original cost less accumulated depreciation is shown to give the

depreciated value of the structures in which the business carries on its

operation. This item could be separated into such things as Factory Building,

Office Building, Warehouse, and any other type of building the business

wishes to show on its statement of financial position.

Equipment The original cost less accumulated depreciation is shown to give the

depreciated value of the equipment used in the operations of the business.

The title equipment may also be separated into whatever special assets of this

type the business cares to identify. The business may use such titles as Office

Equipment for the value of the adding machines, calculators, and typwritters

the office employees use, and Delivery Equipment, for the value of the trucks

and automobiles the business uses to deliver its merchadise to customers. A

manufacturing enterprise would probably show the value of the machines in

its factory as Factory Machinery and Equipment.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 11 of B

Plant, Property and Equipment, Continued

Furniture and

Fixtures The original cost less accumulated depreciation is shown to give the

depreciated value of furniture and fixtures used in the operation of the

business. The title Furniture and fixtures almost explains itself and may also

be subdivided. Desks and chairs and counters used by office employees might

be listed as Office Furniture and Fixtures. Display cases, chairs used by

customers, and merchandise counters in a department store could be entitled

Store Furniture and Fixtures.

Accumulated

Depreciation All property and equipment accounts except land are subject to depreciation.

Depreciation is the allocation of the cost of a property account to its period of

usefulness in order to recognize a decline in its value because of wear and

tear, obsolescence or inadequacy. The total amount of depreciation

accumulated over a number of years is called accumulated depreciation.

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 12 of B

Current Liabilities

Overview Current liabilities are debts or obligations of a business that are expected to be

liquidated by the use of assets classified as current or by the creation of

another current liability.

Accounts

payable The total amount owed by the business as of balance sheet date for purchases

of merchandise, supplies, and services made on a charge account basis and

due within one year from the balance sheet date.

Notes Payable The amounts owed by the business on the basis of formal, signed notes such

as the thirty-day or six-month notes signed when borrowing from a bank. If

merchandise is bought and the creditor requires the business to sign a note for

the amount of the purchase, the title Notes Payable is used. If the same

business borrowed from a bank, the liability may be shown also as Notes

Payable. This is classified as current liability if the note is due within one

year.

Interest

Payable The amount of interest owed by the business as of balance sheet date for

money borrowed on interest bearing promissory notes issued by the firm.

This interest debt builds up each day. The loan is outstanding-the interest

accrues-and it is shown as a separate liability apart from the face value of the

note, which appears in the Notes Payable account.

Deferred

Income Income already collected but not yet earned. Rental payment received by the

lessor from the lessee may be treated as unearned rent income by the former.

Taxes Payable The amount of taxes owed by the business as of balance sheet date.

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 13 of B

Long-Term Liabilities

Overview Long-term liabilities are debts or obligations that will become due and

payable after one year from balance sheet date.

Notes Payable

Long Term Amounts on signed formal notes due after one-year from the date of the

balance sheet.

Installment

Contracts

Payable

Amounts payable after one year from the balance sheet date on long-term

installment notes, such as those signed by the consumers when buying

automobiles and household appliances. Installments due within one year from

the balance sheet date are listed as current liabilities.

Mortgage

Payable A debt due after one year from the balance sheet date that has some of the

business property, such as land, buildings, or equipment-pledged as security.

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 14 of B

Owner’s Equity

Overview Owner’s equity or sometimes called capital or proprietorship is the excess of

assets over liabilities of a business.

Capital The amount invested in the business by the owner as of the balance sheet date.

Withdrawal When the owner withdraws cash or other assets from the business for personal

use, its assets and its owner’s equity both decrease. The amounts taken out of

the business appear in a separate account entitled Withdrawals, or Drawing.

If withdrawals were recorded directly in the capital account, the amount of

owner withdrawals would be merged with owner investments. To separate

these two amounts for decision-making, businesses used a separate account

for Withdrawals. This account shows a decrease in owner’s equity.

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 15 of B

Debit and Credit of Balance Sheet Items

Overview Analyzing business transactions would involve a dual effect in any of the

elements of the accounting equation. These dual effects would be analyzed

and recorded in terms of debit and credit. This part of the study guide will

introduce the readers on the basic understanding of the rules of debit and

credit affecting balance sheet items.

Account The basic summary device of accounting is the account. This is a detailed

record of the changes that have occurred in a particular asset, liability or

owner’s equity during a period of time.

T-Account For the purpose of analyzing the balance items into debit and credit, we will

be using in our illustrations the T-account. It takes the form of the capital

letter “T”. The vertical line in the letter divides the account into its left and

right sides. The account title rests on the horizontal line.

For example, the cash account of a business appears in the following T-

account format:

CASH

Left side

Debit

Right side

Credit

The left side of the account is called the debit side, and the right side is

called the credit side. Often beginners in the study of accounting are

confused by the words debit and credit. To become comfortable using

them, simply remember

debit = left side

credit = right side

The type of an account determines how increases and decreases in it are

recorded. Increases in assets are recorded in the left (the debit) side of

the account. Decreases in the assets are recorded in the right (the

credit) side of the account. Conversely, increases in liabilities and

owner’s equity are recorded by credits. Decreases are recorded by

debits.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 16 of B

Debit and Credit of Balance Sheet Items, Continued

Accounting

Equation This pattern of recording debits and credits is based on the accounting

equations:

ASSETS = LIABILITIES + OWNER’S EQUITY

Rules of Debit Credit Debit Credit Debit Credit

Debit and for for for for for for

Credit Increase Decrease Decrease Increase Decrease Increase

Illustration The following examples illustrate the accounting equations:

Joseph Labrador invested P100,000 cash to begin his accounting

business.

ASSETS = LIABILITIES + OWNER’S EQUITY

Cash Labrador, Capital

Debit

for increase

Php 100,000

Credit

for increase

Php 100,000

The business purchased office supplies on account for P5,000.

ASSETS = LIABILITIES + OWNER’S EQUITY

Office Supplies Accounts Payable

Debit

for increase

Php 5,000

Credit

for increase

Php 5,000

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 17 of B

Debit and Credit of Balance Sheet Items, Continued

Illustration,

con’t. The following examples illustrate the continuation of the accounting

equations:

The business paid one year rental for its office space, P24,000.

ASSETS = LIABILITIES + OWNER’S EQUITY

Prepaid Rent Cash

Debit

for increase

Php 24,000

Credit

for increase

Php 24,000

The business paid ½ of the amount owed in buying office supplies.

ASSETS = LIABILITIES + OWNER’S EQUITY

Accounts Payable Cash

Debit

for increase

Php 2,500

Credit

for increase

Php 2,500

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 1of C

Unit III and IV

Income Statement and Statement of Equity

Overview

Background Owners, management and other stakeholders of the business would want to

know whether the business is earning from its operations. The results of

business operations are summarized and reported in the financial statement

called income statement.

The interval covered by the income statement is known as the accounting

period, i.e., any period usually of twelve months during which business

transactions are recorded and reported upon. When the accounting period

ends on December 31, it is called a calendar period. When it ends on any

month, it is called a fiscal period.

Purpose The purpose of Unit III “Income Statement” is to illustrate how an income

statement may be prepared and the nature of the different accounts included in

the said statement.

Income Statement provides financial information regarding the results of

business operations for a given period of time. It is a report that shows

whether or not the business achieved its primary objective of earning a profit

or net income.

An income statement is prepared by listing

• the revenues earned during the period;

• the expenses incurred in earning the revenue;

• and subtracting the expenses from the revenue to determine if a net income

or a net loss was incurred.

The purpose of Unit IV “Statement of Owner’s Equity” is to show how the

capital statement may be prepared and how withdrawals of proprietor and the

firm’s financial performance may effect the balance of capital at the end of

every accounting period.

In this unit This unit contains the following topics:

Topics See Page

Forms of Income Statement 2 of C

Income Accounts 7 of C

Expense Accounts 8 of C

Debit and Credit of Income Statement

Accounts

10 of C

Statement of Equity or Capital Statement 12 of C

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 2of C

Forms of Income Statement

Overview The forms of income statement that a business prepares depend on the nature

of the business activity undertaken by the firm. As provided in the revised

Philippine Accounting Standard (PAS). 1, service oriented businesses

normally prepare the natural form, formerly known as the single step income

statement and trading and manufacturing firms normally use the functional

form, formerly known as the multiple-step income statement format.

Natural Form The income statement presentation under this form arranges all income

accounts in one group, all expense accounts in another group and then deducts

the total expenses from the total income in a single-step operation of

subtraction to arrive at the final result of net income or net loss.

Illustration Below is an illustration of a natural form income statement:

JOSEPH LABRADOR CONSULTANCY

Income Statement

For the year ended December 31, 20X1 Revenues: Note

Service Income P 650,000

Other Income (1) 50,000 P 700,000

Less: Operating Expenses

Employee Costs (2) P 250,000

Travel & Transportation 100,000

Rent Expense 80,000

Supplies Expense 70,000

Utilities Expense (3) 50,000

Janitorial & Security 32,000

Depreciation Expense (4) 28,000

Commission Expense 17,000

Insurance 14,000

Representation & entertainment 12,000

Repairs & maintenance 9,500

Taxes & Licenses 4,000

Doubtful Accounts 2,000

Miscellaneous Expense 4,000 672,500

Net Income P 27,500

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 3of C

Forms of Income Statement, Continued

Notes to the

Natural Form The following are the notes to the natural form income statement:

Note 1 - Other Income

Interest income P 28,000

Dividend income 22,000

Total other income P 50,000

Note 2 - Employee Costs

Professional fees P 175,000

Salaries & Employee Benefits 75,000

Total employee costs P 250,000

Note 3 - Utilities expense

Telephone & communication P 30,000

Light & Water 20,000

Total utilities expense P 50,000

Note 4 - Depreciation

Depreciation - office equipment 18,000

Depreciation - furniture & fixtures 10,000

Total depreciation P 28,000

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 4of C

Forms of Income Statement, Continued

Functional

Form

The income statement presentation under this form clearly shows specific sections

of income, costs and expenses in a series of arithmetic operations. This form

requires that cost of goods sold and the expenses be subtracted in steps to arrive at

the net income. Merchandising businesses uses this format.

Illustration Below is an illustration of a functional form income statement:

Joseph Labrador Consultancy Income Statement

For the year ended December 31, 20X1

Note

Net sales revenue 1 P 193,000

Cost of sales 2 (145,000)

Gross profit P 48,000

Other operating income 3 3,000

Gross profit and other operating income P 51,000

Operating expenses:

Selling expenses 4 P 14,000

Administrative expenses 5 24,000

Other operating expenses 6 1,000

Interest expense 1,000 (40,000)

Net income P 11,000

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 5of C

Forms of Income Statement, Continued

Notes to the

Functional

Form

The following are the notes to the functional form income statement:

Note 1 - Net sales revenue

Gross sales P 200,000

Less: Sales Returns & Allowances P 5,000

Sales Discount 2,000 7,000

Net sales revenue P 193,000

Note 2 - Cost of sales

Merchandise Inventory, Jan. 1 P 5,000

Add: Net cost of purchases

Purchases P 175,000

Less: Purchase Returns & Allowances P 3,000

Purchase Discounts 2,000 5,000

Net purchase P 170,000

Add: Freight-in 1,000 171,000

Cost of goods available for sale P 176,000

Less: Merchandise Inventory, Dec. 31 31,000

Cost of sales P 145,000

Note 3 - Other operating income

Rent Income P 1,500

Dividend Income 800

Interest Income 500

Gain on Sale of Furniture & Fixtures 200

Total other income P 3,000

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 6of C

Forms of Income Statement, Continued

Notes to the Functional Form (continued)

Note 4 - Selling expenses

Salesmen's Salaries and Commissions P 9,000

Representation and Entertainment 1,200

Depreciation - Store Equipment 1,000

SSS & Philhealth Premiums 900

Freight-out 800

Miscellaneous Selling Expense 1,100

Total selling expenses P 14,000

Note 5 - Administrative expenses

Salaries Expense P 15,000

Light, Water and Telephone 3,500

Uncollectible Accounts 2,000

Depreciation Expense 1,500

SSS & Philhealth Premiums 1,300

Miscellaneous General Expense 700

Total administrative expenses P 24,000

Note 6 - Other operating expenses

Loss on Sale of Equipment P 800

Discount Lost 200

Total other operating expenses P 1,000

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 7of C

Income Accounts

Overview The following are the usual income statement account found in a single-step

income statement

Service Income Different businesses have different ways of earning income. The term that is

generally used to refer to any kind of income from services rendered is service

income. This represents the inflow of cash or non-cash assets arising from

services rendered. Other account names that may be used to refer to income

from services describes the specific nature of the service rendered: (Pefianco,

E., Mercado, R., 1983)

• Professional Fees. These indicate income from rendering professional

services without specifying the particular nature of professional service

rendered.

• Medical Fees. This refers to income received from rendering medical

services.

• Legal Fees. This refers to income received from rendering legal services.

• Dental Fees. This refers to income received from rendering dental services.

• Accounting Fees. This refers to income received from rendering

accounting services.

• Management Fees. This refers to income received from rendering various

management consultancy services.

Other Income This refer to income from sources other than the principal line of activity of

the business.

The examples of other income are:

• Interest Income. The revenue to the payee for loaning out a principal

amount to a borrower. This may also refer to income earned from money

deposited in a bank.

• Dividend Income. Income earned in investing cash in stocks of other

businesses.

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 8of C

Expense Accounts

Overview Expenses are the cost of goods or services that are used or consumed in the

operations of a particular business activity. In service businesses, the

following are the common expenses

Salaries This is the cost of services rendered by the employees and/or laborers of a

business firm. This account may be used to include the cost of all emergency

allowances, 13th month pay, and other employee fringe benefits.

Rent The rental cost of office space, equipment, etc.

Office Supplies This refers to the cost of office stationery; coupon bond, carbon paper,

typewriter or computer ribbons, envelopes, pencils, ball pens, and office

supply items that are consumed in business operations.

Utilities This refers to the cost of light and water consumed as well as the cost of using

telephone facilities.

Taxes and

Licenses This refers to all payments required to be made to the Bureau of Internal

Revenue and the Municipal Treasurer for privilege taxes, mayor’s permits,

municipal taxes and licenses, business taxes and others.

Transportation This is the cost incurred by office employees when commuting from the office

to the place of business of clients, e.g., jeepney fares, taxi fares, and bus fares.

Also included are transportation fares from the office to any place on official

business. Travelling Expense is used when business trips are made out of

town, the cost of transportation fares by plane, by boat, or by bus.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 9of C

Expense Accounts, Continued

Gas and oil This refers to the cost of gas and oil consumed whenever transportation

vehicles or company cars are used in official business trips.

Representation The cost incurred when entertaining clients or prospective clients. Included

are the costs incurred when office employees represent the firm in some

official functions.

Depreciation This refers to the expense associated with the use of the company’s plant

assets, i.e., spreading (allocating) the cost of a plant asset over its useful life.

Bad Debts Selling or rendering services on credit create both a benefit and a cost. Credit

customers who fail to pay their liabilities will create an expense in the

company. The allocation or provision for this future uncollectibility of some

of the accounts of credit customers is called bad debts expense or doubtful

accounts expense or uncollectible account expense.

Donations and

Contributions This refers to contributions made to charitable institutions or any other

worthwhile projects.

Miscellaneous Any other costs of operations that may not be sufficiently big in amount to be

classified separately are charged to this account.

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 10of C

Debit and Credit of Income Statement Accounts

Overview A business transaction is an activity that involves the exchange of values. This

exchange would result to a situation or receiving a value equal to the value

given away. In this part, we would learn the simple mechanics of these

activities which bring about changes in the income statement.

Revenues The purpose of a business, other than to render service to the community, is to

increase assets and owner’s equity through revenues, which are amounts

earned by delivering goods or services to customer. Revenues increase

owner’s equity because they increase the business’s assets but not its

liabilities. As a result, the owner’s interest in the assets of the business

increases.

• Example: Jose Labrador earns service income by providing professional

accounting service for his clients. Assume he earns P10,000 and collects

this amount in cash. The effect on the accounting equation is an increase in

the asset cash and an increase in Labrador Capital due to the income

generated.

Assets - Cash = Liabilities + Labrador, Capital

10,000 increase 10,000 increase - Service income

Expenses In earning revenue, a business incurs expenses. Expenses are decreases in

owner’s equity that occur in the course of delivering goods and service to

clients. Expenses decrease owner’s equity because they use up the business

assets.

• Example: During the month, Labrador paid the salary of the company

secretary for P5,000. The effect on the accounting equation is a decrease in

the asset, cash and a decrease in capital due to the expense incurred.

Asset - Cash = Liabilities + Labrador, Capital

5,000 decrease 5,000 decrease - Salaries expense

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 11of C

Debit and Credit of Income Statement Accounts, Continued

Normal

Balance Upon analyzing the effects of income and expense accounts in the owner’s

equity, one may conclude that, since owner’s equity or capital has a normal

credit balance, it must follow that all income accounts will also have normal

credit balances since they cause an increase in the capital account. On the

contrary, since expenses have a decreasing effect in the capital account, the

normal balance of all expense accounts would be debit.

The illustration presents two main sources of owner’s equity, namely:

investments and revenues. On the other hand, withdrawals and expenses

decrease the owner’s equity.

INCREASES DECREASES

Expenses Revenues

Owner ‘s Equity

Owner withdrawals

from the business Owner investments

in the business

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 12of C

Statement of Equity or Capital Statement

Overview Capital Statement or Statement of Owner’s Equity presents a summary of

the changes that occurred in the owner’s equity of the entity during a specific

time period, e.g., month or a year. Increases in owner’s equity arise from

investments by the owner and net income earned. Net loss for the period

causes the owner’s equity to decrease. Net Income or net loss comes directly

from the income statement. Investments and withdrawals by the owner are

capital transactions between the business and its owner, so they do not affect

the income statement.

Withdrawals The owner of the firm would at times withdraw assets from the business for

personal use. These personal withdrawals would be treated differently

depending on the intention of the owner in withdrawing such assets

Types of

Withdrawals • Temporary Withdrawal. The owner withdraws business assets (e.g. cash)

for personal use in anticipation of profits derived from the operations of the

business. This type of withdrawal uses the drawing account when recorded

in the books of the company.

The pro-forma entry to record this type of withdrawal is:

Joseph Labrador, Drawing xxx

Cash or Other Assets xxx

To record withdrawal of owner for personal use

• Permanent Withdrawal. Capital withdrawal that is substantial in amount.

The owner in this type of withdrawal of the assets has the intentions of

removing the asset permanently from the business operations. This type of

drawing uses the capital account.

The pro-forma entry to record this type of withdrawal is:

Joseph Labrador, Capital xxx

Cash or Other Assets xxx

To record permanent withdrawal of asset of owner from the business.

Continued on next page

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 13of C

Statement of Equity or Capital Statement, Continued

Statement of

Owner’s Equity The statement of owner’s equity opens with the owner’s capital balance at the

beginning of the period. Add net income, (deduct in the case of net loss)

which directly comes from the income statement. Subtract withdrawals by the

owner and the statement ends with owner’s capital balance at the end of the

period.

Illustration Below is the illustration of the statement of the owner’s equity.

JOSEPH LABRADOR, CPA

Statement of Owner’s Equity

For the year ended December 31, 20X1

Joseph Labrador, Capital, January 1 P 620,500

Add: Net Income 34,500

Sub-Total P 655,000

Less: Joseph Labrador, drawing 10,000

Joseph Labrador, Capital, December 31 P 645,000

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 14of C

Unit V

Statement of Cash Flows

The basic financial statements we have presented so far provide only limited information about

the company’s asset “Cash”. For example, balance sheet shows how much cash the business

owns on the date the report was prepared but it does not indicate the amount of cash generated by

operating activities, or financing activities. The income statement may show expenses and

revenues that may have an effect to cash but will not provide reader of this report how these

income and expenses affected “Cash” account. The capital statement shows what happened to

the capital balance of the owner during the year. None of these statements presents a detailed

summary of where cash came from and how it was used.

Statement of Cash Flows Defined

The statement of cash flows reports the cash receipts, cash payments, and net change in cash

resulting from operating, investing, and financing activities during a period.

Usefulness of the Statement of Cash Flows

The information in a statement of cash flows should help investors, creditors, and others assess:

1. The entity’s ability to generate future cash flows. By examining relations between

items in the statement of cash flows, investors and others can make predictions of the

amounts, timing, and uncertainty of future cash flows better than they can from accrual

basis data.

2. The entity’s ability to pay dividends and meet obligations. If a company does not

have adequate cash, it cannot pay employees, settle debts, or pay dividends. Employees,

creditors, and stockholders should be particularly interested in statement, because it alone

shows the flows of cash in a business.

3. The reasons for the difference between net income and net cash provided (used) by

operating activities. Net income provides information on the success or failure of a

business enterprise. However, some are critical of accrual basis net income because it

requires many estimates. As a result, the reliability of number is often challenged. Such

is not the cash with cash. Many readers of statement of cash flows want to know the

reasons for the difference between net income and net cash provided by operating

activities. Then they can assess for themselves the reliability of the income number.

4. The cash investing and financing transactions during the period. By examining a

company’s investing and financing transactions, a financial statement reader can better

understand why assets and liabilities changed during the period.

Marivic D. Valenzuela-Manalo Page 15of C

Classification of Cash Flows