ABA SECTION OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT LAW … · and (4) ... itamae-sushi chefs, who prepare and...

Transcript of ABA SECTION OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT LAW … · and (4) ... itamae-sushi chefs, who prepare and...

ABA SECTION OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT LAW 4th ANNUAL CLE CONFERENCE

THE WAGE & HOUR TRACK GET IN THE GAME: THE LATEST NEWS AND

DEVELOPMENTS IN WAGE AND HOUR LITIGATION CHICAGO, IL

November 5, 2010

David Borgen Goldstein, Demchak, Baller, Borgen & Dardarina

300 Lakeside Drive, Suite 1000 Oakland, CA 94612 Tel: (510) 763-9800 Fax: (510) 835-1417

[email protected] www.gdblegal.com

Dennis M. McClelland Phelps Dunbar LLP

100 South Ashley Drive, Suite 1900 Tampa, FL 33602

Tel: (813) 472-7550 Fax: (813) 472-7570

[email protected] www.phelps.com

James M. Finberg Altshuler Berzon LLP

177 Post Street, Suite 300 San Francisco, CA 94108

Tel: (415) 421-7151 Fax: (415) 362-8064

[email protected] www.altshulerberzon.com

Paul L. Bittner Schottenstein Zox & Dunn Co., LPA

250 West Street Columbus, OH 43215

Tel: (614) 462-2228 Fax: (614) 221-3190 [email protected]

www.szd.com

Janet Herold Director

National Wage & Hour Enforcement Project

Service Employees International Union 2629 Foothill Blvd., #351 La Crescenta, CA 91214

Tel: (818) 957-7334 Fax: 818 542-6419

TABLE OF CONTENTS1

Page

Update Re Tip Income Issues (David Borgen) ...................................................................1

Notable 2010 Exemption Cases (Paul L. Bittner) ..............................................................12

Compensable Time (James M. Finberg) ............................................................................27

FLSA Coverage: Employee or Independent Contractor? (Dennis M. McClelland) ..........34

FLSA Retaliation: Are Internal Workplace Complaints Protected Activities under Section 15(a)(3)? (Dennis M. McClelland) .............................................47

Pending Regulatory and Legislative Matters (Janet Herold) .............................................57

1 This paper contains a collection of separately written papers on various wage and hour law “hot topics.” The

order of the articles is random and not intended to be in any particular order of importance. The articles were prepared individually by the identified authors to be informative on the subjects and do not express any particular views on behalf of the panel or the American Bar Association.

UPDATE RE TIP INCOME ISSUES

Federal and state law governing tipped employee wages continues to develop. A large

segment of the economy works in the service sector and routinely receives tips in addition to

hourly wages—particularly low wage workers. See Rajesh D. Nayak & Paul K. Sonn, National

Employment Law Project, Restoring the Minimum Wage for America’s Tipped Workers (Aug.

2009).2

FLSA Developments

The FLSA permits an employer to utilize a “tip credit” to pay “tipped employees” a sub-

minimum wage under certain circumstances. 29 U.S.C. § 203(m). Four conditions must be met

in order for an employer to qualify for a tip credit: (1) employers may only apply the tip credit to

a “tipped employee” as defined by the FLSA, meaning an employee engaged in an occupation

who customarily and regularly receives more than $30 a month in tips. 29 U.S.C. § 203(t); (2)

the employer may not apply the tip credit to the wages of an employee “unless such employee

has been informed by the employer of the provisions of [29 U.S.C. §203(m)].” 29 U.S.C. §

203(m); (3) the employee must receive at least minimum wage when direct wages and tips are

combined. Id. Employers may pay tipped employees as little as $2.13 per hour, as long as their

employees earn at least $5.12 per hour in tips to match the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per

hour, as of July 24, 2010.3 Id.; 29 U.S.C. § 206(a)(1); see also Dep’t of Labor Fact Sheet #15:

Tipped Employees Under the Fair Labor Standards Act, available at

http://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/compliance/whdfs15.pdf; and (4) all tips received by an employee

must be retained by her, except when the employee contributes her tips to a valid tip pool

“among employees who customarily and regularly receive tips.” 29 U.S.C. § 203(m).

2 Available at http://www.nelp.org/site/publications/P100/. 3 Although the federal minimum wage has been gradually increasing according to a set schedule, the base

amount the employer pays stays at the 1996 level of $2.13. 29 U.S.C. § 203(m).

Limits on § 203(m)’s Tip Pooling Restrictions

The Ninth Circuit recently held that the FLSA does not restrict tip pooling arrangements

where the employer does not take a tip credit for its employees’ wages. In Cumbie v. Woody

Woo, Inc., 596 F.3d 577, 578, 583 (9th Cir. 2010), an employer paid its employees at or

exceeding Oregon’s minimum wage and the federal minimum wage. Id. at 578. The plaintiff

server alleged that the tip-pooling arrangement violated the FLSA. Upholding the trial court’s

dismissal of plaintiff’s action, the court reasoned that § 203(m) only “imposes conditions on

taking a tip credit and does not state freestanding requirements pertaining to all tipped

employees,” and therefore there was “no basis for concluding that [the employer’s] tippooling

arrangement violated section 203(m).” Id. at 581. The court further rejected plaintiff’s and the

DOL’s argument that the tip-pooling arrangement violated 29 U.S.C. § 206, as interpreted in 29

C.F.R. § 531.35, by constituting a prohibited kickback to the kitchen staff for the employer’s

benefit. Id. at 581-82. The court explained that because “[t]he FLSA does not restrict tip

pooling when no tip credit is taken,” “only the tips redistributed to Cumbie from the pool ever

belonged to her, and her contributions to the pool did not, and could not, reduce her wages below

the statutory minimum.” Id. at 582.

Tipped Employees

What types of employees are “tipped employees”?

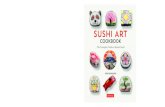

The DOL issued an opinion letter in late 2008 regarding the “tipped employee status” of

itamae-sushi chefs, who prepare and serve sushi to customers in a bar area, and teppanyaki chefs,

who prepare meals on the teppan table located at customer tables and serve meals to customers.

Opinion Letter, FLSA2008-18 (Dec. 19, 2008). It opined that these types of employees were

“tipped employees,” explaining that they provided customer service similar to “counter persons

who serve customers” that the DOL has long considered to be appropriate tip pool participants.

Id. (citing DOL Field Operations Handbook §30d04(a)).

In 2009, a jury found that Quality Assurance personnel (QAs), or Expeditors, employed

by Chili’s restaurants did not work in positions that customarily and regularly received tips. See

Roussell v. Brinker Int'l, Inc., No. 4:05-cv-03733, 2009 WL 3149612 (S.D. Tex. Apr. 29, 2009).

QAs worked in the “pass through” area of Chili’s kitchens, inspected food passed through by the

cooks, ensured that it conformed with guests’ orders, monitored ticket times, and helped ensure

quick delivery of food. Roussell v. Brinker Int’l, Inc, 2008 WL 2714079, *2 (S.D. Tex. 2008).

Factors weighing against a finding that QAs “customarily and regularly” received tips were lack

of customer interaction and customer service duties, and an industry custom of tip pool

participation by QAs. An appeal to the Fifth Circuit is now pending in the Chili’s case.

Tipped Employees Who Perform Both Tipped and Non-Tipped Duties

Some employees perform some duties or functions that traditionally produce tips (e.g.,

providing table service to customers at restaurants) and some duties or functions which do not

produce tips (e.g. cleaning restaurant bathrooms or preparing food). Cases have dealt with the

distinction between (1) an employee’s performance of a “dual job”4 in which one “job”

performed by an employee produces tips and the other job does not (e.g. when a maintenance

man in a hotel also serves as a waiter) and (2) an employee’s performance of duties for which

4 29 C.F.R. § 531.56(e) provides: In some situations an employee is employed in a dual job, as for example, where a maintenance man in a hotel also serves as a waiter. In such a situation the employee, if he customarily and regularly receives at least $20 a month in tips for his work as a waiter, is a tipped employee only with respect to his employment as a waiter. He is employed in two occupations, and no tip credit can be taken for his hours of employment in his occupation of maintenance man. Such a situation is distinguishable from that of a waitress who spends part of her time cleaning and setting tables, toasting bread, making coffee and occasionally washing dishes or glasses. It is likewise distinguishable from the counterman who also prepares his own short orders or who, as part of a group of countermen, takes a turn as a short order cook for the group. Such related duties in an occupation that is a tipped occupation need not by themselves be directed toward producing tips.

employees are generally not tipped, but are “related duties in an occupation that is a tipped

occupation.” 29 C.F.R. §531.56(e). An employee is not a “tipped employee” for purposes of the

tip credit and tip pool participation when performing a non-tipped “dual job.” See id. On the

other hand, an employer maybe able to take the tip credit for hours spent performing “related

duties.” See id.

In the Chili’s case, the district court determined that servers who spent separate shifts as

QA personnel held “dual jobs.” Roussell v. Brinker, No. H-05-3733, 2008 WL 2714079 (S.D.

Tex. July 9, 2008). On its motion for summary judgment, Chili’s argued that servers who

worked as QAs were performing tasks incidental to their work as a server, and thus may be

considered “tipped employees” during their QA shifts.” Id. at *12. The court rejected this

argument, relying on 29 C.F.R. § 531.56(e)’s distinction between dual jobs and “related duties.”

The court concluded that while servers’ performance of QA tasks “intermittently during their

shifts as servers” would likely be “considered incidental to a server’s job,” servers who worked

entirely separate shifts as QAs were employed in a “dual job.” Id. at *13. It reasoned that

“[t]here was . . . a clear dividing line between the servers’ duties as a server and the servers’

duties as a QA,” because servers worked separate shifts as QAs, clocked in and were paid as

QAs, and performed duties under a separate QA job description. Id. The court thus held that

servers could not be considered “tipped employees” eligible for participation in a tip pool during

shifts they worked as QAs. Id. at *14.

Another issue is how much “related” or “incidental” non-tipped work an employee may

perform before an employer must pay the full minimum wage for that time. In Fast v.

Applebee’s International, Inc., No. 06-4146-CV-C-NKL, 2010 WL 816639, at *7 (W.D. Mo.

Mar. 4, 2010), a court adopted an standard in the DOL Field Operations Handbook which

provides that “where the facts indicate that specific employees are routinely assigned to

maintenance, or that tipped employees spend a substantial amount of time (in excess of 20

percent) performing general preparation work or maintenance, no tip credit may be taken for the

time spent in such duties.” The court rejected Applebee’s argument that that the determination

of whether the tip credit applied should be determined on the basis of the “occupation” of the

employee. This interpretation would permit Applebee’s to “have its servers and bartenders

perform an unlimited amount of non-tipped duties while Applebee’s pays them the tipped wage,

so long as those non-tipped duties are related in some amorphous or ever changing way to the

occupation of servers or bartenders.” Id. at *6. The 20% standard, on the other hand, “ensure[d]

that employers will not lose the tip credit until they assign substantial work that is not tip

producing” but also recognized that a “reasonable limit had to be placed on the amount of work

that could be assigned that was not customer specific.” Id. at *5.

An interlocutory appeal of the court’s denial of summary judgment of this and other

issues is now pending before the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals. However, several courts have

also adopted the 20% rule. See Ash v. Sambodromo, LLC, 676 F. Supp. 2d 1360, 1366 (S.D.

Fla. 2009) (ruling that that if certain employee’s duties are “incidental to one of the employee’s

tip producing duties . . . then the employer may take the tip credit for the time the employee

spent on incidental duties so long as the incidental duties do not exceed 20 percent of the

employee’s overall duties”); Holder v. MJDE Venture, LLC, No. 1:08-CV-2218-TWT, 2009 WL

4641757, *3-4 (N.D. Ga Dec. 1, 2009) (ruling that the “the Fair Labor Standards Act required

the Defendants to pay the Plaintiff the full minimum wage for substantial time spent on work that

did not produce tips” and whether plaintiffs spent more than 20% of their workday on non-tipped

tasks was genuinely disputed); Plewinski v. Luby’s, Inc., No. H-07-3529, 2010 WL 1610121, at

*5 (S.D. Tex. April 21, 2010) (adopting 20% rule for purposes of class certification motion).

Other courts, however, have declined to apply the 20% rule. In Driver v. AppleIllinois,

265 F.R.D. 293, 311 (N.D. Ill. 2010), a district court evaluated whether to certify for class

treatment a plaintiff’s claim that her employer improperly paid her sub-minimum wage for non-

tipped duties. In doing so, it rejected the 20% approach and adopted the defendant’s more

“workable” proposed standard, which would be “to determine whether a particular duty is part of

a tipped occupation.” Id. In Pellon v. Business Representation International, Inc., 528 F. Supp.

2d 1306, 1314 (S.D. Fla. 2007), a district court rejected the application of the 20% rule to

evaluate the tipped and non-tipped duties of skycaps, concluding that “a determination whether

20% (or any other amount) of a skycap’s time is spent on non-tipped duties is infeasible.” The

court also noted that the 20% rule would not apply in any event, as the skycaps did not perform

the “general preparation work or maintenance” referenced in the Handbook, that plaintiffs had

offered insufficient evidence that their non-tipped duties constituted more than 20% of their

workday, and that all of the non-tipped tasks at issue “properly fall within the skycap

occupation” and “do not establish dual jobs.” Id.

§ 203(m)’s Notice Requirement

Employers must provide employees notice under § 203(m). “Although an employer need

not ‘explain’ the tip credit to an employee, Courts have widely interpreted § 203(m) to require at

a minimum that an employer inform its employees of its intention to treat tips as satisfying part

of the employer's minimum wage obligations.” Bernal v. Vankar Enters., 579 F.Supp.2d 804,

810 (W.D. Tex. 2008); see Kilgore v. Outback Steakhouse of Florida, Inc., 160 F.3d 294, 299-

300 (6th Cir. 1998) (written statement describing use of tip credit was sufficient notice); Pellon,

528 F. Supp. 2d at 1310-11 (oral notice that employee’s salary would be $2.15 (or more) plus

tips and prominently displayed poster regarding the tip credit were adequate notice); but see

Chan v. Sung Yue Tung Corp., No. 03 Civ. 6048(GEL), 2007 WL 313483 (S.D.N.Y Feb. 1,

2007) (finding hanging of poster in language that most employees did not understand was not

sufficient notice).

In Bernal, a Texas court rejected an employer’s argument that its servers were aware that

it would take tip credits because the practice was “industry standard.” Id. at 809. The court

reasoned that “if [it] were to permit Defendants to substitute their statutory responsibility for an

alleged general awareness of an industry-wide practice, the notice prerequisite of section 203(m)

would be satisfied in every instance, and section 203(m) would be rendered mere surplusage.”

Id. at 809-10.

A Georgia court recently rejected an employer’s argument that an employee’s awareness

that her salary was $2.15 per hour and that she could keep all of her tips satisfied § 203(m)’s

notice requirement. Holder v. MJDE Venture, LLC, No. 1:08-CV-2219-TWT, 2009 W 4641757,

at *2 (N.G. Ga. Dec. 1, 2009). Quoting the First Circuit in Martin v. Tango's Restaurant, Inc.,

969 F.2d 1319, 1323 (1st Cir. 1992), the court ruled “[t]hat an employee expected to earn and

retain their tips . . . does not suggest even mildly that the employee knew anything of the

minimum wage laws of defendants’ intention to claim a tip credit against their obligations.” Id.

at *2.

The court in Pedigo v. Austin Rumba, Inc., --- F. Supp. 2d ---, 2010 WL 2730462, *7

(W.D. Tex. June 17, 2010) followed this reasoning as well. There, a court rejected defendant’s

argument that an employee’s request for an hourly wage of $2.13 plus tips on their employment

application showed that an employee was “aware” of tip credit provisions and thus satisfied §

203(m)’s notice requirement.

Assignment of the Burden of Proving the Applicability of the Tip Credit

A number of courts have recently ruled that the defendant employer in a tip credit case

“bears the burden of establishing that it is entitled to claim the ‘tip credit’.” Ash v. Sambodromo,

676 F. Supp. 2d at 1369; Pedigo, 2010 WL 2730462, at *6; Bernal, 579 F. Supp. 2d at 808

(“Defendants, as the employers, bear the burden of proving that they are entitled to taking tip

credits.”). In Pedigo, the court noted that “section 203(m) does not constitute an independent

cause of action available to employees under the FLSA. Rather section 203(m) is a partial

exception to the minimum wage requirements of section 206 that exists for tipped employees.”

2010 WL 2730462 at *6 (internal quotation marks and brackets omitted) (quoting Scherrer v.

S.J.G. Corp., No. A-08-CA-190-SS, 2008 WL 7003809, at *1 (W.D. Tex. Oct. 10, 2008)).

Employers therefore bear the burden of proving the tip credit because “the general rule is that the

application of an exemption under the Fair Labor Standards Act is a matter of affirmative

defense on which the employer has the burden of proof.” Id. (quoting Corning Glass Works v.

Brennan, 417 U.S. 1888, 196-97 (1974)).

On the other hand, in Fast, a district court assigned to the employee the burden of proving

a prima facie case as to the inapplicability of the tip credit. The court acknowledged that

assigning the burden to the employer would be consistent with the case law discussed above,

“with the doctrine that where the facts with regard to an issue lie peculiarly in the knowledge of a

party, that part has the burden of proving the issue,” and “the common law rule that all

circumstances, of justification, excuse or alleviation rest on the defendant.” 2010 WL 816639,

*8 (quoting Dixon v. United States, 548 U.S 1, 9 (2006)) (internal quotation marks omitted).

Even so, noting that it had “not located a single case in which a court actually required an

employer to prove the number of hours for which an employee was properly paid the tipped

wage,” the court applied the burden shifting approach outlined in Anderson v. Mt. Clemens

Pottery Co., 328 U.S. 680 (1946):

Under this precedent, the Court believes that Plaintiffs must do more than show they were paid at the tipped wage rate of $2.13 per hour. . . . Before the burden shifts to Applebee’s, Plaintiffs must make a prima facie showing which hours were not properly paid “as a matter of just and reasonable inference.”

Id. at *10 (quoting Mt. Clemens, 328 U.S. at 687).

Voluntary Tip Pools

The Chili’s case, discussed above, also addressed the voluntariness of participation in tip

pools. Because the FLSA does not prohibit tipped employees from voluntarily sharing their tips

with other employees, including non-tipped employees, Chili’s asserted that the tip pool between

servers and QA employees was valid because, regardless of whether QA employees were “tipped

employees,” servers had voluntarily shared their tips with QAs. Denying Chili’s motion for

summary judgment on the issue, the court set forth a standard for determining whether

employees in a tip pool shared their tips voluntary or coerced. 2008 WL 2714079, at *18. The

court rejected Chili’s proposed standard: whether the actions of management “well might have

dissuaded, by force or threat, a reasonable Server from believing that tipping out a QA was

voluntary.” Id. (emphasis added). Instead, the court adopted a standard set forth by the DOL

Field Operations Handbook: “Employees may share tips with other workers who are not

customarily and regularly tipped if they do so ‘free from any coercion whatever and outside any

formalized arrangement or as a condition of employment.” Id. (citing Handbook §§ 30d01(a),

30d04(c)) (internal quotation marks omitted) (emphasis added).

California State Law Developments

State law regarding tipped employees may differ from the FLSA’s provisions in

significant ways. California, Alaska, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, and

the territory of Guam, do not permit employers to use a tip credit or to pay a sub-minimum wage.

Accordingly, in these states, contrary to federal law, state law prohibitions on tip pooling—such

as its prohibitions on employer tip pool participation—are independent from any statutory

provisions regarding the tip credit. Cumbie v. Woody Woo, 596 F.3d at 581 (holding that 29

U.S.C. § 203(m) “imposes conditions on taking a tip credit and does not state freestanding

requirements pertaining to all tipped employees”).

Tip Pool Participants

In Budrow v. Dave & Buster’s of California, Inc., 171 Cal. App. 875 (2009), a California

court of appeal held that bartenders could participate in a mandatory tip pool with servers. In

Etheridge v. Reins Int’l California, Inc. 91 Cal. Rptr. 3d 816, 828 (Ct. App. 2009), another court

of appeal concluded that all employees who “contribute” to a patron’s service could be included

in tip pools which in June 2009, the California Supreme Court denied plaintiffs’ petitions for

review in both Budrow and Etheridge.

Tip Pool Participation by Employers or Their Agents

In 2009, a California Court of Appeal held that Starbuck’s policy of distributing tips from

a collective tip box placed next to a cash register did not violate prohibitions on tip pooling under

California law. Chau v. Starbucks Corp., 171 Cal. App. 4th 688, 706 (2009). Under Starbucks’

policy, tips deposited in this collective box were distributed to (1) “baristas,” who were “entry-

level, part-time hourly employees responsible for customer service related tasks, such as working

the cash register and making coffee drinks;” and (2) “shift supervisors,” who were “also part-

time hourly employees who perform all the duties of a barista, but are also responsible for some

additional tasks, including supervising and coordinating employees within the store, opening and

closing the store, and depositing money into the safe.” Id. at 692. The court concluded that

Starbucks’ policy should be considered “tip apportionment” rather than “mandatory tip pooling.”

Id. at 700. The California Supreme Court denied the plaintiffs’ petition for review in September

2009.

Private Rights of Action Under State Law

Two state courts have recently addressed whether state laws governing tipped employees

create private rights of action for citizen enforcement. In Lu v. Hawaiian Gardens Casino, Inc., -

-- Cal. Rptr. 3d ---, 2010 WL 3081272 (Aug. 9, 2010) the California Supreme Court held that

California Labor Code § 351—California’s statute governing tipped employees, does not contain

a private right of action.5 The court left the door open for plaintiff’s Unfair Competition Law

claim, which was predicated on section 351, for administrative remedies, and for tort claims such

as conversion.

Lu follows the Nevada Supreme Court’s decision that Nevada Revised Statute 608.160,

which also prohibits employers from taking employees’ tips and from applying tip credits, does

not create a private right of action. Baldonado v. Wynn Las Vegas, LLC, 194 P.3d 96, 102 (Nev.

2008).

5 Section 351 prohibits employers from taking any gratuity left by patrons for employees and states that such

gratuities are “the sole property of the employee or employees to whom it was paid, given, or left for.”

NOTABLE 2010 EXEMPTION CASES

Introduction

This section of the materials covers some noteworthy cases concerning exemption issues

from 2010.

Executive Exemption

In Vanstory-Frazier v. CHHS Hospital Co., LLC, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 387, 2010 WL

22770 (E.D. Pa. 2010), the Eastern District of Pennsylvania denied summary judgment to the

employer in a matter where the employee plaintiff sought overtime under the FLSA. The

employer had claimed that the plaintiff was exempt as either an executive or administrative

employee. The Court found that the plaintiff could not be considered exempt as an executive

employee because, although she had supervisory responsibility, she had no authority to hire or

fire other employees and there was no evidence that she made suggestions regarding any change

in employee status that were given particular weight. It was unclear as to whether or not her

“supervisory” responsibilities were her most important duties and, therefore, a factual issue

remained as to whether her primary duty was directly related to management under the

administrative exemption.

The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois issued a decision on a “novel”

issue in Ottaviano v. Home Depot, Inc., USA, 701 F. Supp.2d 1005 (N.D. Ill. 2010). In

Ottaviano the plaintiffs alleged that Home Depot had violated Illinois state law regarding the

payment of overtime by maintaining a policy where any assistant store manager who regularly

worked less than 55 hours per week would be terminated. Home Depot paid assistant store

managers on a salary basis, and under Illinois law, if the employees were exempt under the

FLSA, they would also be exempt under state law. According to the plaintiffs, the policy of

terminating employees who worked less than 55 hours per week violated the salary basis test

under the FLSA. The Court granted summary judgment in favor of Home Depot. The question

that was presented was narrow, to wit: whether termination is tantamount to a wage reduction

that would violate the salary basis test under the FLSA. Reviewing existing case law from the

Seventh Circuit, the Court held that employees do not lose an exemption simply because they are

subject to discipline for failing to work a particular schedule. Taking plaintiffs’ argument

further, the Court suggested that employers would be subject to liability for terminating

employees who do not work a predetermined schedule.

Administrative Exemption

Probably most noteworthy in 2010 is the Department of Labor’s Division of Wage and

Hour official withdrawal of the Bush-era opinion letter regarding mortgage loan officers and the

administrative exemption. Under the previous guidance from the Wage and Hour Division,

mortgage loan officers could be considered exempt administrative professionals if they were

compensated on a salary basis of at least $455 per week and exercised discretion and

independent judgment providing guidance to customers as to mortgage loan products.

According to Administrator’s Interpretation No. 2010-1 issued on March 24, 2010,

mortgage loan officers’ typical job duties do not meet the administrative exemption. According

to the Wage and Hour Division, a careful analysis of the applicable statutory and regulatory

provisions and a thorough review of the case law leads to the conclusion that mortgage loan

officers who perform their typical job duties do not qualify as bona fide administrative

employees under the FLSA. Mortgage loan officers typically receive internal leads and contact

potential customers or receive contacts from customers generated by direct mail or other

marketing activity. These loan officers then collect financial information from these customers

and use computer programs that identify which loan products may be offered to customers based

upon the financial information provided. Likening the duties of a mortgage loan officer more to

production rather than staff, the Administrator points out that historically mortgage loan officers

were compensated on a commission-basis, are trained in sale techniques and evaluated based on

their sales volume. The mortgage loan officers’ primary duty is making sales and should not be

covered by the administrative exemption. The Administrator specifically rejects the conclusion

reached in Wage and Hour Opinion Letter FLSA 2006-31 (September 8, 2006), noting that the

regulation provides an example to help distinguish between those employees in the financial

services industry whose primary duty is related to the management or general operation of the

employer’s customers and those who are primarily selling. The test set forth within §541.203(b)

is not an alternative test and its guidance cannot result in swallowing the requirements of

§541.200.

In Robinson-Smith v. Government Employees Insurance Company, 590 F.3d 886 (D.C.

Cir. 2010), the D.C. Circuit overturned summary judgment that had found GEICO violated the

FLSA by misclassifying its adjusters as exempt. On appeal, the panel found that the lower court

erred in finding that the discretion used by the adjusters in settling insurance claims was not

sufficient to qualify under the administrative exemption.

The Second Circuit ruled that an advertising sales director for the magazine Elite

Traveler was not exempt as an administrative employee in Reiseck v. Universal Communications

of Miami, Inc., 591 F.3d 101 (2d Cir. 2010). Originally, Universal Communications obtained

summary judgment from the District Court on this application of the exemption, but on appeal,

the Circuit Court found that, because the plaintiff did not engage in the promotion of sales

generally, she did not engage in the primary duty of administrative work. Instead, the Court

found that her primary duty was selling advertising space to individual customers. An employee

making specific sales is a salesperson while, according to the Court, an employee who is

encouraging an increase in sales generally among all customers is an administrative employee.

Although the lower court’s decision was vacated, the Circuit Court remanded the case for

consideration as to whether the plaintiff was exempt as either an outside sales employee or a

commission sales representative.

Unlike some of the cases discussed herein regarding the outside sales exemption, Johnson

& Johnson successfully defended an unpaid overtime claim by one of its pharmaceutical sales

representatives. In the matter of Smith v. Johnson & Johnson, 593 F.3d 280 (3d Cir. 2010), the

plaintiff sought overtime although she received an annual salary of $66,000 and a bonus based

upon the total number of prescriptions that were written in her territory. According to the Court,

the plaintiff was required to use a high level of planning and foresight to maximize sales and

operated in an unsupervised manner 95% of the time. She was given a budget to cover her

marketing efforts and had her own budget. She was expected to plan and prioritize activities in a

manner that would maximize sales. The planning involved administrative work and she clearly

met the salary requirements required for the job. At one point, the Court cited that the discretion

and independent judgment that she used was self-described as a “manager of her own business”

and that she could “run her own territory as she saw fit.”

Similarly, Alpharma successfully defended an overtime claim brought by a class of

pharmaceutical sales representatives in Jackson v. Alpharma Inc., 2010 U.S. Dist LEXIS 72435,

2010 WL 2869530 (D.N.J. 2010). In Jackson, the Court waited until the ruling in Smith, supra,

prior to briefing on Alpharma’s motion for summary judgment. The Court found that the

primary duty of the sales representatives was the performance of non-manual work directly

related to the general business operations, that is, they were involved in functional areas such as

advertising, marketing, promoting sales and similar activities. Relying on the holding in Smith

where the Alpharma representatives essentially received a sales territory and expense account

and developed their own business plans for growth and their day-to-day activities, the Jackson

Court found that the representatives exercised discretion and independent judgment.

In Andrade v. Aerotek, Inc., 700 F. Supp.2d 738 (D.Md. 2010), a staffing services firm

recruiter was deemed to meet the administrative exemption where she performed personnel

management and human resources work directly for her employer’s clients as well as office work

directly related to management and business operation of the firm’s customers. The plaintiff

used discretion in developing strategies, selecting candidates and negotiating pay among other

things. The plaintiff had asserted that she was not acting in an administrative capacity; however

the Court found that, in her duties as a recruiter and an account recruiting manager, she worked

in functional areas such as personnel management and human resources. In relying upon a 2005

opinion letter, the Court concluded that this type of work was the type of work directly related to

management or general business operations contemplated in the regulations and that she also

exercised discretion in independent judgment with respect to matters of significance when she

selected candidates to be sent to the client’s hiring manager for approval. The Court stated that

the hiring of employees is certainly work that affects business operations to a substantial degree.

On May 3, 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari in Whalen v. JPMorgan

Chase and Co., 587 F.3d. 529, cert. denied, 130 S. Ct. 2416 (2d Cir. 2009). JPMorgan Chase

had asked the Court to hear an appeal from a decision in favor of an employee who worked for

the bank as a home equity loan underwriter. The plaintiff claimed that he was not properly

classified and, therefore was entitled to overtime pay. The Second Circuit found that his primary

duty was more akin to sales than administrative work. According to the Second Circuit, the job

of underwriter was production rather than administrative, as the plaintiff was directly engaged in

creating the goods, i.e. the loans and other financial services, produced and sold by Chase.

Professional Exemption

Helicopter pilots had been treated as professional employees by the Port Authority of

New York and New Jersey. A District Court ruled in 2008 that the employees were in fact not

“professionals” under the FLSA regulations. In January 2010, the Third Circuit affirmed the

judgment of the district court in Pignataro v. Port Auth. of New York and New Jersey, 593 F.3d

265 (3d Cir. 2010). In conducting an analysis of the professional exemption, the Circuit Court

stated that the employer could not show that being a helicopter pilot is work that requires

knowledge of an advanced type in a field of science or learning acquired by a long course of

specialized intellectual instruction and study. While helicopter pilots have specialized

knowledge and unique skills, because these skills are acquired through experience and

supervised training as opposed to academic instruction and intellectual study, they do not meet

the exemption. Moreover, helicopter pilots’ flight certificates do not require advanced academic

degrees. These employees are more like highly trained technicians than learned professionals

and, therefore, are entitled to premium pay for time worked in excess of 40 hours per work week.

The Pignataro ruling is consistent with the view of the Department of Labor that pilots are not

FLSA exempt professionals because aviation generally is not a field of science or learning that is

contemplated by the professional exemption. Note that the Third Circuit’s holding is

inconsistent with a 1983 ruling from the Fifth Circuit in Paul v. Petroleum Equipment Tools,

Co., 708 F.2d, 168 (5th Cir.1983).

In another professional exemption case, Young v. Cooper Cameron Corp., 586 F.3d 201

(2d Cir. 2009), the plaintiff was a product design specialist who worked on hydraulic power units

for the oil and gas industry. His employer, Cooper Cameron Corp., asserted that he was not

entitled to overtime because he was an exempt professional. The plaintiff had 20 years of

experience in engineering in different positions such as draftsman and designer but did not have

a college degree. The plaintiff was employed as a Product Design Specialist 2 and according to

the job description, a successful candidate needed twelve (12) years of relevant experience but

did not specify any particular education. The plaintiff was the principal in charge of drafting

certain types of hydraulic power units. After being terminated in a reduction in force, he brought

a suit under the FLSA for overtime. Turning on the issue of whether or not the particular job

performed by the plaintiff met the exemption for learned professional, the Court analyzed

whether the knowledge required to perform the job was customarily acquired by a prolonged

course of specialized intellectual instruction and study. Recognizing that the “customarily

acquired” applies in a vast majority of cases where academic training is a prerequisite for the

professional position, there are some exceptions for the occasional professional who has not

attained the specialized degree but has attained the status through extensive experience in the

field.

The employer had argued that a position can be exempt notwithstanding the lack of an

educational requirement. The plaintiff argued that, if advanced and specialized education is not

customarily required, the exemption cannot apply regardless of the employee’s duties. What the

Circuit Court did with some precision was clarify its interpretation of the regulations. An

exempt professional can include the “occasional” person who did not complete formal education

to be placed in a profession that ordinarily requires a formal education. However, merely

because a job requires some advanced skills does not make the holder of the job a professional.

The Court stated, “we therefore hold that an employee is not an exempt professional unless his

work requires knowledge that is customarily acquired after a prolonged course of specialized,

intellectual instruction and study. If a job does not require knowledge customarily acquired by

an advanced educational degree – as for example when many employees in the position have no

more than a high school diploma – then, regardless of the duties performed, the employee is not

an exempt professional under the FLSA. Id. at 206.

Computer-Related Exemption

In Verkuilen v. Media Bank, LLC, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 77407, 2010 WL 3003860

(N.D. Ill. 2010), an accounts manager worked for a company that provided software and services

to clients in the advertising industry. In this role, the plaintiff provided software support services

for her employer’s clients and acted as a liaison between those clients and the programmers and

software developers employed by the employer. The plaintiff also assisted clients when they ran

into problems with the software. According to the job description, the accounts manager

position managed the relationship with clients, including everything from the day-to-day

information requests to in-depth analysis to contract renewal negotiations and training and

support needs. The Court found that the plaintiff was covered by the administrative exemption

because her primary duty was the performance of office or non-manual work directly related to

her employer’s general business operations and that such work involved the exercise of

discretion and independent judgment with respect to matters of significance. However, the Court

dismissed the alternative theory that the plaintiff was exempt because she was also a computer-

related employee. The employer had conceded that the plaintiff was not a computer systems

analyst, computer programmer or software engineer. Rather, the employer argued that the

plaintiff was a similarly skilled employee. The Court determined that the plaintiff did not have

skills similar to that of any of the employees that she relied upon for computer programming.

The Court noted that the plaintiff’s position did not require any type of degree in the computer

field; it required a bachelor’s degree with a background in marketing or market research. What

is probably most noteworthy about this case as it relates to the computer-related exemption is

that the Court focused on the plaintiff’s formal education. The plaintiff did not have specific

training or a degree in the computer field. A specific degree in computer programming or in the

computer field is not required, however, to meet the computer-related exemption.

Outside Sales Exemption

Two recent federal cases have found in favor of pharmaceutical sales representatives

concerning overtime claims. In June 2010, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of

Illinois granted summary judgment in favor of a class of plaintiffs against Abbott Labs in Jirak,

et al. v. Abbott Laboratories, Inc., 2010 U.S. Dist LEXIS 58804, 2010 WL 2331098 (N.D. Ill.

2010). The plaintiffs in Jirak were responsible for generating market share and growth for

certain Abbott products and making “selling presentations” but not promoting the products to

patients or end-users. After analyzing the issues, the Court found that the sales representatives

for Abbott Labs did not make sales, but were more akin to marketers and promoters. When

cross-motions for summary judgment were filed by the parties, the Court found in favor of

plaintiffs on liability and retained jurisdiction to determine any back overtime and damages due

the plaintiffs.

On July 6, 2010, another pharmaceutical company, Novartis, had a decision originally in

its favor overturned by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. In In re Novartis Wage

and Hour Litigation, 611 F.3d 141 (2d Cir. 2010), overtime claims for a class of approximately

2500 sales representatives were reinstated and remanded to the trial court. The trial court

originally found that the Novartis sales representatives were in fact exempt under the outside

sales and administrative exemption and thus, not entitled to overtime pay. On appeal, the

plaintiffs, joined by the U.S. Secretary of Labor as amicus curiae, argued that in fact, the

representatives did not make sales. The Circuit Court pointed out that when delivering

“samples” to physicians, no money actually changes hands. If it did, such a “sale” would be a

federal crime. Ultimately, the claims for overtime compensation were reinstated and the only

likely issues left for the trial court to determine are back overtime and damages due the plaintiffs.

Note that both Johnson & Johnson and Alpharma had better success asserting the administrative

exemption, discussed above.

Highly Compensated Exemption

In Ogden v. CDI Corp., 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 66686, 2010 WL 2662274 (D.Ariz.

2010), the plaintiff accepted a position as a recruiter for CDI Corp. CDI is a professional

services company that provides staffing to its clients. The plaintiff routinely worked more than

40 hours per week but was not paid any overtime. Much of the plaintiff’s compensation was

commission based. Although it was not disputed that Ogden earned enough to qualify as a

highly compensated employee, Ogden contested whether or not his job also included the

customary and regular performance of one or more of exempt duties. The employer asserted that

he did perform the exempt duties of an administrative employee. In examining the portions of

plaintiff’s deposition, Ogden performed work that included searching for individuals who might

be qualified for certain IT jobs and determining whether the candidate’s background matches a

job order placed by a client. He used both subjective and objective factors to determine whether

or not an individual fit within the client’s stated needs. The plaintiff would then provide these

candidates to his account manager who would decide whether to present the candidates to the

client.

There was a fact question as to whether Ogden was making these decisions on his own or

if he was merely applying a set criteria and forwarding that information on to his account

manager. In contrasting the decision to deny summary judgment with Andrade, supra, the Court

pointed out that Plaintiff did not have the responsibility of communicating directly with the

employer’s clients on a regular basis and there was no evidence that the plaintiff had the

authority to discipline, manage, coach and counsel the candidates after placement.

Retail Employee Under 29 U.S.C. §207(i)

Two cases from 2010 that are noteworthy related to the Section 7(i) exemption are

discussed herein. In the first, Alvarado v. Corporate Cleaning Service Inc., 2010 U.S. Dist.

LEXIS 62378, 2010 WL 2523432 (N.D. Ill. 2010), the District Court denied the employer’s

motion for summary judgment related to the 7(i) exemption. The plaintiffs, 24 current and

former window washers, sought overtime pay. The employer asserted that they employees were

covered under 7(i) and therefore exempt. The first issue the Court resolved was a window-

washing business, even one that primarily provides services to other businesses, is properly

considered retail. The plaintiffs argued that the employer did not sell to the “general public.”

The Court, thoroughly discussed the notion of retail, found that simply because the services

provided by the employer were sold to other business, such as high rise buildings and

condominium associations, does not remove the employer from the retail concept in 7(i).

The Court then turned its attention to the commission-based pay requirement of 7(i), as

the parties stipulated that the employees earned at least 1.5 times the minimum wage for all

hours worked. The window washers were paid on a “point” system, wherein they were paid

basically on a per-window basis. Regardless of the length of time it took or the number of

employees on a job, the total number of windows resulted in a point total which then in turn

affected compensation for the job. The employer could not demonstrate that the price charged to

the customer per point correlated to the total points credited to the washers. Instead, there was

evidence that indicated that unpaid debts, competitive market pressures, customer relations, and

human error could impact the price charged per point. The Court ultimately determined that

such a system in not necessarily inconsistent with a commission-based pay scheme; however, for

purposes of summary judgment, there was a material fact questions that could only be resolved

with proof at trial.

A more clear-cut determination concerning commissions was announced in Parker v.

NutriSystem, Inc., 2010 U.S. App. LEXIS 18691, 2010 WL 3465054 (3d Cir. 2010). The issue

in Parker concerned what is a bona fide commission under Section 7(i), as the term is not

defined in the FLSA. The employees sold NutriSystem’s meal plans via telephone sales. Each

employee received set amounts for each fixed-price product sold and there were different

amounts paid to the employees for incoming or outgoing calls and whether the sales were for

single month or recurring plans. The Department of Labor urged the Court to afford Skidmore

deference to its view that a commission must be linked to the cost of the product sold or services

provided to the customer, i.e., that an increase in the cost to the consumer must result in a

corresponding increase to the amount of the payment make to the employee. Skidmore v. Swift &

Co., 323 U.S. 134 (1944). The Court declined such afford such deference. The Parker Court

refused to find that a commission must vary based upon the end cost to consumers because a

strict percentage relationship is not required for a commission under Section 7(i). Instead, a flat-

rate payment made to an employee based on that employee’s sales proportionally related to the

charges passed on to the consumer can be properly considered commissions.

Motor Carrier Exemption

In April 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review a ruling of the Eleventh Circuit

that affirmed a district court’s rejection of claims for overtime by shuttle bus drivers. Walters v.

Am. Coachlines of Miami, Inc., 575 F.3d 1221 (11th Cir. 2009), cert. denied, 130 S. Ct. 2343.

These shuttle bus drivers asserted that they were entitled to overtime because their employer was

essentially only involved in intrastate transportation. The employer, ACLM, is a private motor

carrier that is licensed by the Department of Transportation. Accordingly, ACLM is authorized

by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration to operate as an interstate passenger motor

carrier. Although the company transports passengers between Florida and other states, 96% of

the company’s revenues come from intrastate travel. According to the Court, the fact that there

was a small amount of interstate travel did not render the appropriate federal licensing

unnecessary and that there is undisputed proof that some transportation crosses state lines.

In June 2010, a district court in Mississippi rejected the overtime claims on behalf of

drivers of soft drink trucks. In Jackson v. Brown Bottling Group, LLC, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS

58736, 2010 WL 2519650 (S.D. Miss. 2010), a truck driver asserted that he should be entitled to

overtime for making intrastate deliveries of soft drinks on behalf of a soft drink distributor. Even

though he never transported the products across state lines, it was undisputed that the driver

operated on public highways and delivered products that were shipped with the intent of being

moved continuously from bottlers’ out-of-state facilities to the distributor’s warehouse and then

to customers generally within twelve days. The employer asserted that the plaintiff was not

entitled to overtime compensation under the FLSA because the plaintiff fell within the motor

carrier exemption contained within the Motor Carrier Act. This Act exempts employees to

whom the Secretary of Transportation has the power to establish qualifications and maximum

hours of service. Upon review of the Motor Carrier Act itself, the Secretary of Transportation’s

jurisdiction would include coverage of such an individual, as he is a carrier that engages in

interstate commerce by either actually transporting goods across state lines or transporting within

a single state goods that are in the flow of interstate commerce. The Court determined that the

plaintiff was engaged in moving product that was in the stream of interstate commerce.

Enterprise Coverage Under 29 U.S.C. §203(s)

In Polycarpe v. E & S Landscaping Service, Inc., 2010 U.S. App. LEXIS 18171, 2010

WL 33998825 (11th Cir. 2010), the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals was asked to determine

whether the district courts properly dismissed claims asserted against the defendant employers by

concluding that the employers were not required to comply with the requirements of the FLSA.

Under the FLSA, an employer is required to comply with its mandates if the employer (1) “has

employees engaged in commerce or in the production of goods for commerce, or that has

employees handling, selling, or otherwise working on goods or materials that have been moved

in or produced for commerce by any person”; and (2) has at least $500,000.00 of “annual gross

volume of sales made or business done.” 29 U.S.C. §203(s)(1)(A). The Polycarpe Court

focused upon whether the defendant employers fell within the handling clause of this provision.

Specifically, whether the employers had any employees “handling, selling, or otherwise working

on underlying goods or materials, have been moved in or produced for commerce by any

person.” 29 U.S.C. §203(s)(1)(A)(i).

In determining whether the handling clause applies, the Court first addressed and then

rejected the doctrine commonly referred to as the “coming to rest doctrine.” Several courts have

interpreted this doctrine as excluding interstate goods or materials that have come to rest within

the state before they are purchased within the state by the employer. The Polycarpe Court then

addressed the interplay between the terms “goods” and “materials” as defined under the handling

clause. The distinction between these terms is significant because “the ultimate consumer”

defense is available if an item is considered a “good.” This defense is not available if the item is

considered only “materials.” The ultimate consumer defense is set forth in 29 U.S.C. §203(i):

“goods … does not include goods after the delivery and to the actual physical possession of the

ultimate consumer thereof other than a producer, manufacturer, or processor thereof.” The

determination as to whether an item constitutes “materials” rather than a “good” will depend

upon the following: “(1) whether, in the context of its use, the item fits within the ordinary

definition of “materials” under the FLSA, and (2) whether the item is being used commercially

in the employers business.” “Materials” are, therefore, interpreted for purposes of the FLSA as

“tools or other articles necessary for doing or making something.” The Court used china plates

as an example to illustrate this test. When a catering business uses china plates as service to its

customers, the plates are considered materials. When a department store sells the china plates,

they are considered goods. If an accounting firm uses the china plates as a decorative item in its

lobby, the plates are not materials because they do not have a significant connection to the firm’s

business.

The Polycarpe Court ultimately reversed the district courts’ dismissals on five of the six

cases that had been dismissed based upon an application of the “coming to rest doctrine.” The

sixth case was affirmed because there was uncontroverted evidence that the employer did not

meet the $500,000.00 revenue test.

Although the Polycarpe Court clarified that its holding would not be “so expansive as to

be limitless,” application of this decision will likely expand coverage of the FLSA to many

additional employers located within the Eleventh Circuit encompassing Florida, Georgia, and

Alabama. The employer may no longer rely upon the fact that the goods or materials handled by

its employees had “come to rest” within the state before purchased by the employer. If the

employer meets the $500.000.00 annual revenues test, the employer can avoid enterprise

coverage only by showing that its employees do not regularly handle, sell or work on materials

that have changed hands through interstate commerce, and that the employer is the ultimate

consumer for any interstate good that its employees do handle.

Disclaimer: These materials have been prepared by Schottenstein Zox & Dunn Co., LPA for discussion purposes only and are not intended to constitute legal advice.

COMPENSABLE TIME

1. Pre- And Post-Shift Donning And Doffing Is Compensable Under the FLSA.

The Fair Labor Standards Act requires employers to compensate employees for all hours

worked. 29 U.S.C. §§203, 207; 29 C.F.R. §778.223. In Anderson v. Mt. Clemens Pottery Co.,

328 U.S. 680 (1946), the Supreme Court held that time spent by employees walking from the

entrance of their employer’s premises to their work location is working time within the meaning

of the FLSA. In a legislative effort to lessen the effects of this ruling, Congress passed the

Portal-to-Portal Act amendments to the FLSA. Among other things, those amendments to the

FLSA excluded from working time travel time to or from the actual place of performance of the

“principal activity” or activity which is “preliminary to or postliminary to said principal

activity.” 29 U.S.C. §254(a).

Notwithstanding the Portal-to-Portal Act, however, “activities performed either before or

after the regular work shift” are compensable “if those activities are an integral and indispensable

part of the principal activities.” Steiner v. Mitchell, 350 U.S. 247, 256 (1956) (emphasis added).

The United States Supreme Court recently re-affirmed Steiner, holding in a donning and doffing

case involving a meat packing plant that activities that are integral and indispensable to principal

activities are themselves principal activities. IBP, Inc. v. Alvarez, 546 U.S. 21, 33, 37 (2005).

An activity is “integral and indispensable” if it is “necessary to the principal work performed and

done for the benefit of the employer.” Alvarez v. IBP, 339 F.3d 894, 902-03 (9th Cir. 2003),

aff’d on other grounds, 546 U.S. 21.

Further, any walking time that occurs after the beginning of an employee’s first principal

activity and prior to the end of the employee’s last principal activity, is compensable. See

Alvarez, 546 U.S. at 37. This is the “continuous workday rule,” in accordance with which “the

‘workday’ is generally defined as ‘the period between the commencement and completion on the

same workday of an employee’s principal activity or activities.’” Alvarez, 546 U.S. at 29.

Otherwise non-compensable time (such as walking) is compensable as part of the continuous

workday if it occurs after the first principal activity and before the last principal activity.

The application of these principles was discussed by the Ninth Circuit in Alvarez. That case

involved the donning and doffing of certain protective equipment by employees in a meat

packing plant. The court concluded that the time spent donning and doffing such equipment was

compensable under the FLSA. It was “integral and indispensable” because it was “necessary to

the principal work performed and done for the benefit of the employer.” 339 F.3d at 902-03.

The court found that it was “necessary” because it was required by law, the rules of the

employer, and the nature of the work. Id. The court further held that “it is beyond cavil that the

donning, doffing, washing, and retrieving of protective gear is, at both broad and basic levels,

done for the benefit of” the employer. Id. Among other things, the court noted in this context

that the donning of such equipment was done to “prevent unnecessary workplace injury and

contamination, both of which would inevitably impede” the employer’s production. Id

Similarly, where “‘the changing of clothes on the employer’s premises is required . . . by

rules of the employer, or by the nature of the work,’ the activity may be considered integral and

indispensable to the principal activities.” Ballaris v. Wacker Siltronic Corp., 370 F.3d 901, 910

(9th Cir. 2004) (quoting 29 C.F.R. §790.8(c) n.65).

In addition to affecting the meat packing industry, there have been “donning and doffing”

claims in the automobile industry, among other industries. Automobile manufacturers have

recognized their liability for this time and settled such claims for substantial amounts. See, e.g.,

Martin v. NUMMI, Case No. C07-03887 PJH (N.D. Cal.) (settlement of $4.65 million in 2009);

Steve Lannen, Toyota Pays Walking Time For Paint Shop Workers, Lexington Herald-Ledger

(Feb. 17, 2008) ($4.5 million settlement); BMW Agrees To Pay $629,000 In Back Wages for

1,224 Workers At South Carolina Assembly Plant, U.S. Dep’t of Labor News Release (Aug. 1,

2006).

2. Time That is Measurable and Occurs Regularly is Not De Minimis

In “donning and doffing” cases defendants frequently invoke the de minimis exception to

the FLSA. Specifically, they argue that the amount of time spent donning and doffing is too

insignificant to matter for purposes of calculating overtime compensation.

“[I]n determining whether otherwise compensable time is de minimis,” a court “will

consider (1) the practical administrative difficulty of recording the additional time; (2) the

aggregate amount of compensable time; and (3) the regularity of the additional work.” Lindow v.

United States, 738 F.2d 1057, 1063 (9th Cir. 1984).

In a Wage & Hour Advisory Memorandum, the U.S. Department of Labor has clarified

that the donning and doffing time is recoverable, even if the individual components are small, if

the aggregate amount of time is measurable and exceeds the de minimis threshold. Wage and

Hour Advisory Memorandum No. 2006-2 at 3.6

6 In the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Alvarez, the court stated that “the time it takes to” “don[]

and doff[] non-unique protective gear such as hardhats and safety goggles” “is de minimis as a matter of law” and therefore noncompensable. 339 F.3d at 903. However, based on a portion of the Supreme Court’s subsequent opinion in Alvarez, the Department of Labor has explained that:

the Ninth Circuit erred in its application of the de minimis rule. The de minimis rule applies to the aggregate amount of time for which an employee seeks compensation, not separately to each discrete activity, and particularly not to certain activities “as a matter of law.” The Supreme Court’s continuous workday rationale renders the Ninth Circuit’s “de minimis as a matter of law” discussion untenable.

Wage and Hour Advisory Memorandum No. 2006-2 at 3. According to DOL, the

Supreme Court’s decision in “Alvarez . . . clearly stands for the proposition that where the aggregate time spent donning, walking, waiting and doffing exceeds the de minimis standard, it is compensable. Any other conclusion would be inconsistent with the continuous workday

3. Personal Protective Equipment Differs From “Clothing”

The FLSA contains an exception for “any time spent in changing clothes” that is

excluded from compensation under “the express terms of or by custom or practice under a bona

fide collective-bargaining agreement.” 29 U.S.C. §203(o) (“Section 3(o)”). Employers in

donning and doffing cases sometimes raise Section 3(o) as an affirmative defense. To invoke

this exception, employers first have to establish that the personal protective equipment at issue is

“clothing” within the meaning of the exception.

In Alvarez v. IBP, the Ninth Circuit held that the garments at issue must “‘plainly and

unmistakably’ fit within § 3(o)’s ‘clothing’ term” for the clothes-changing exception to apply.

Alvarez, 339 F.3d at 905. Moreover, the court held that because Section 3(o) is a FLSA

exemption, the clothing term must be narrowly construed. Id. (citing Arnold v. Ben Kanowsky,

Inc., 361 U.S. 388, 392 (1960)). Thus, the court expressly rejected IBP’s argument that

“‘clothes’ must mean ‘whatever is worn as covering for the human body,’” and instead held that

Section 3(o) applies only to “typical clothing.” Alvarez, 339 F.3d at 904-05 (emphasis added).

Applying these principles, the court concluded that the IBP employees’ personal protective gear

did not qualify as clothing under Section 3(o). Id.

On June 16, 2010, the Wage and Hour Division of the Department of Labor issued an

interpretation of the term “clothes” in §203(o), and of whether clothes changing covered by

§203(o) is a principal activity. Administrator’s Interpretation No.2010-2 (June 16, 2010).

With respect to what are “clothes,” the Administrator advised that “[b]ased on its

statutory language and legislative history, it is the Administrator’s interpretation that the §203(o)

exception does not extend to protective equipment worn by employees that is required by law, by

rule.” Id. at 4. In any event, there is no indication that California would adopt this particular statement from the Ninth Circuit’s opinion in Alvarez.

the employer, or due to the nature of the job.” The Administrator clarified that portions of its

2002 letter and the entirety of its 2007 letter, suggesting a different interpretation “should no

longer be relied upon.”

4. Section 3(o) Only Applies to Express Terms or Custom or Practice Mutually Agreed to Under a Bona Fide Collective-Bargaining Agreement.

Even if the items being donned and doffed are “clothes” within the meaning of Section

3(o), to assert to section 3(o) exemption, the employer must establish that this donning and

doffing time is excluded from “hours worked” for compensation purposes “by the express terms

of or by custom or practice under a bona fide collective-bargaining agreement.” 29 U.S.C.

§203(o).

Section 3(o) applies only to a “custom or practice under a bona fide collective bargaining

agreement.” 29 U.S.C. §203(o) (emphasis added). It is fundamental that a contractual

agreement must be mutual to be enforceable. This statutory language makes clear that Section

3(o) applies only if the parties to the CBA mutually agreed upon the custom or practice of

nonpayment. It does not apply where the employer unilaterally established a practice of

nonpayment. The agreement need not be expressly memorialized in the CBA, but whether

express or implied the agreement must be mutual.

The legislative history of Section 3(o) confirms that Congress intended to exempt

clothes-changing time only where the union and employer mutually agreed to do so. When

Congressman Herter proposed the amendment, he explained:

In some of those collective-bargaining agreements the time taken to change clothes and to take off clothes at the end of the day is considered a part of the working day. In other collective-bargaining agreements it is not so considered. But, in either case the matter has been carefully threshed out between the employer and the employee and apparently both are completely satisfied with respect to their bargaining agreements.

95 Cong. Rec. 11,433 (1949) (emphasis added). Even employers advocating for Section 3(o)

denied that the exemption would permit employers to unilaterally establish a custom or practice:

“We are not suggesting that evasion of the act be permitted by providing that the workweek be

only what the employer says it is.” Statement on Behalf of the Baking Industry as Presented by

William A. Quinlan, General Counsel, Associated Retail Bakers of America, at 1177-78. (Exh.

50) (excerpt). The employer-proponents further assured Congress that “the suggested provision

would place the burden of proof upon the employer, a burden which would preclude any abuse

. . . .” Id.

Construing “custom or practice under a bona fide collective bargaining agreement” to

encompass only mutually accepted practices is also consistent with the Ninth Circuit’s holding

that Section 3(o) must be construed narrowly against the employer. Alvarez, 339 F.3d at 905. A

more expansive interpretation of the custom-or-practice term would conflict with FLSA’s

remedial purposes. As one district court persuasively reasoned:

Certainly, the statutory language “custom and practice under a bona fide collective-bargaining agreement” means more than “this is the way we’ve always done it,” for that amounts to nothing more than saying that once an illegal practice gets started, it becomes “immunized” from challenge over time. Mere silence alone cannot confer on a particular practice the status of a “custom and practice under a bona fide collective-bargaining agreement.” Properly construed, the language requires some showing that the employer and the union have reached an agreement by implication that a certain practice is acceptable and, thus, the employer can take comfort in relying on it.

Fox, 2002 WL 32987224, at *8. See also Kassa v. Kerry, Inc. 487 F.Supp.2d 1063, 1071 (D.

Minn. 2007) (“If an employer’s history of nonpayment for clothes-changing time were sufficient,

by itself, to establish a ‘custom or practice’ under §203(o), then §203(o) would essentially be an

unlimited FLSA exemption applicable to every unionized employer that did not pay for clothes-

changing time. The Court does not believe that §203(o) is so sweeping.”).

5. Even if the Changing of Clothes is Not Compensable Pursuant to the Contract or Past Practice, it may be a “Principal Activity” That Starts the Continuous Work Day.

“Generally, donning and doffing, which may include clothes changing, can be a

‘principal activity’ under the Portal to Portal Act, 29 U.S.C. § 254, IBP v. Alvarez, 346 U.S.21.30

(2005).” DOL Wage and Hour Administrator’s Interpretation No. 2010-2. Contrary to the

weight of authority, in 2007 the DOL issued an opinion letter indicating §203(o) activities cannot

be principal activities. In its June 16, 2010 Administrator’s Interpretation No. 2010-2, the DOL

Wage and Hour Administrator clarified that “[c]onsistent with the weight of authority, it is the

Administrator’s interpretation that clothes changing covered by §203(o) may be a principal

activity. Where that is the case, subsequent actions, including walking and waiting are

compensable.” Accordingly, even if certain time changing clothes at the start of a work day is

not compensable by mutual agreement, that principal activity still starts the continuous work day.

Id.

FLSA COVERAGE: EMPLOYEE OR INDEPENDENT CONTRACTOR?7

Perhaps no area of labor and employment law has received more attention in 2010 than

the issue of so-called “worker misclassification” (the classification of workers as independent

contractors instead of employees). In June 2010, the United States Department of Labor vowed

to “combat” misclassficiation through regulatory reform, increased enforcement efforts, and

partnering with States.8 Additionally, on April 21, 2010, the Senate proposed legislation (the

“Employment Misclassification Prevention Act”), which, if enacted, would add recordkeeping

and notice requirements, increase penalties, and comprehensively reform the manner in which

government agencies work together to address misclassified workers.9 Many state governments

have a renewed emphasis on “cracking down” on misclassification through legislative change

and increased enforcement efforts to ensure that the states receive the appropriate tax revenue

and workers receive appropriate benefits and protections.10

Despite this recent emphasis on misclassification issues, the legal standards under the Fair

Labor Standards Act (“FLSA”) used to determine whether a worker is an employee or independent

contractor have remained largely unchanged since 1943. Over time, however, legal decisions

around the country have provided valuable insight as to how courts apply these legal standards to a

variety of different factual settings. This paper provides an overview of the law applied to

7Substantial portions of this article are reprinted from Part II.C (“Employee or Independent Contractor”) in

Chapter 3 (“Coverage”) of the Second Edition of the Fair Labor Standards Act Treatise (Kearns, ed.), which will be published by the ABA and BNA Books in 2010. This article, however, includes some citations to more recent cases that were decided after the drafting of the Second Edition of the FLSA Treatise.

8“Statement of Seth Harris, Deputy Secretary, U.S. Department of Labor, Before the Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, U.S. Senate” (June 17, 2010), http://www.dol.gov/_sec/newsletter/2010/20100617-2.htm. 9See S. 3254, the "Employee Misclassification Prevention Act" (April 21, 2010).

10“Statement of Seth Harris, Deputy Secretary, U.S. Department of Labor, Before the Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, U.S. Senate” (June 17, 2010), http://www.dol.gov/_sec/newsletter/2010/20100617-2.htm.; see also “Ohio Cracks Down on Worker Misclassficiation,” http://www.ohioscpa.com/PublicArticle.aspx?ID=543.

determine when workers are “employees” covered by the FLSA and when they are “independent

contractors” not covered by the FLSA.

1. General Principles

The economic reality test is most often applied in determining whether a particular worker is

an independent contractor—who is not covered by the FLSA—or a covered employee. Neither

contractual or other labeling of a worker as an independent contractor nor common law standards

regarding independent contractor status will be determinative of whether a worker is an employee

under the Act.11 However, employer treatment of workers as employees is highly probative

evidence of an employer-employee relationship.12

When a putative employer asserts that the individual involved is an independent contractor,

courts review the totality of the circumstances in determining the economic reality of the

relationship. The Supreme Court, in United States v. Silk,13 found the following factors to be

relevant considerations in determining employee status:

(1) degree of control,

11Rutherford Food Corp. v. McComb, 331 U.S. 722, 6 WH Cases 990 (1947); Brock v. Superior Care, 840 F.2d

1054, 28 WH Cases 801 (2d Cir. 1988); Robicheaux v. Radcliff Material, 697 F.2d 662, 25 WH Cases 1210 (5th Cir. 1983); Donovan v. Sureway Cleaners, 656 F.2d 1368, 25 WH Cases 105 (9th Cir. 1981); Usery v. Pilgrim Equip. Co., 527 F.2d 1308, 22 WH Cases 783 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 429 U.S. 826, 22 WH Cases 1281 (1976); McClure v. Salvation Army, 460 F.2d 553, 557 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 409 U.S. 896 (1972); Wirtz v. Lone Star Steel Co., 405 F.2d 668, 18 WH Cases 687 (5th Cir. 1968); Varnish v. Best Medium Publ’g Co., 405 F.2d 608 (2d Cir. 1968); Hefferman v. Illinois Cmty. Coll. Dist. No. 508, 2000 WL 631309, 6 WH Cases2d 132 (N.D. Ill. May 16, 2000) (denying defendant’s motion to dismiss, noting that “an independent contractor ‘label does not necessarily take the worker from the protection of the Act’” (quoting Dole v. Amerlink Corp., 729 F. Supp. 73, 76, 29 WH Cases 1019 (E.D. Mo. 1990))).

12Superior Care, 840 F.2d at 1059 (concluding employer’s treatment of taxed nurses, who performed same functions as nontaxed nurses, was “highly probative” in determining employment status of nontaxed nurses); Sureway Cleaners, 656 F.2d 1368 (observing workers performed jobs integral to business and of same nature as at facilities where workers were admittedly employees); Hodgson v. Taylor, 439 F.2d 288, 19 WH Cases 982 (8th Cir. 1971) (concluding workers who loaded railroad cars at night performed identical duties to employees loading cars during day); Tobin v. Anthony-Williams Mfg. Co., 196 F.2d 547 (8th Cir. 1952) (observing employer admitted employees performed work identical to workers whom employer disclaimed as employees); cf. Mitchell v. John R. Cowley & Bros., Inc., 292 F.2d 105, 107, 15 WH Cases 106 (5th Cir. 1961) (determining watchman performed same duties as he performed under predecessor employer that considered him employee).

13331 U.S. 704 (1947). See discussion in Section I [Overview] and Section II.B [The Employer-Employee Relationship; The Economic Reality Test], above.

(2) investment in facilities,

(3) opportunity for profit and loss,

(4) permanency of the relationship, and

(5) required skill.14

Other courts have used these or similar factors, with several adding a sixth factor:

whether the service rendered is an integral part of the alleged employer’s business.15 The degree

of control continues to be a major component of any analysis.16

14Id. at 716. 15First Circuit: Baystate v. Alternative Staffing, Inc. v. Herman, 163 F.3d 668 (1st Cir. 1998) (adding sixth

factor to test). Second Circuit: Brock v. Superior Care, 840 F.2d 1054 (2d Cir. 1988) (employing five-factor test). Third Circuit: Martin v. Selker Bros., Inc., 949 F.2d 1206 (3d Cir. 1991) (employing six-factor test); Donovan