Marine Mammals Cetacea Mysticeti (Baleen Whales) – 15 species

A Tale of Two Mysticeti THIS SIDEBAR DOES NOT PRINT QUICK...

Transcript of A Tale of Two Mysticeti THIS SIDEBAR DOES NOT PRINT QUICK...

RESEARCH POSTER PRESENTATION DESIGN © 2012

www.PosterPresentations.com

(—THIS SIDEBAR DOES NOT PRINT—)

DESIGN GUIDE

This PowerPoint 2007 template produces a

91cmx122cm presentation poster. You can use it to

create your research poster and save valuable time

placing titles, subtitles, text, and graphics.

We provide a series of online tutorials that will guide

you through the poster design process and answer your

poster production questions. To view our template

tutorials, go online to PosterPresentations.com and

click on HELP DESK.

When you are ready to print your poster, go online to

PosterPresentations.com

Need assistance? Call us at 1.510.649.3001

QUICK START

Zoom in and out As you work on your poster zoom in and out to

the level that is more comfortable to you. Go

to VIEW > ZOOM.

Title, Authors, and Affiliations Start designing your poster by adding the title, the names of

the authors, and the affiliated institutions. You can type or

paste text into the provided boxes. The template will

automatically adjust the size of your text to fit the title box.

You can manually override this feature and change the size of

your text.

TIP: The font size of your title should be bigger than your

name(s) and institution name(s).

Adding Logos / Seals Most often, logos are added on each side of the title. You can

insert a logo by dragging and dropping it from your desktop,

copy and paste or by going to INSERT > PICTURES. Logos

taken from web sites are likely to be low quality when

printed. Zoom it at 100% to see what the logo will look like

on the final poster and make any necessary adjustments.

TIP: See if your school’s logo is available on our free poster

templates page.

Photographs / Graphics You can add images by dragging and dropping from your

desktop, copy and paste, or by going to INSERT > PICTURES.

Resize images proportionally by holding down the SHIFT key

and dragging one of the corner handles. For a professional-

looking poster, do not distort your images by enlarging them

disproportionally.

Image Quality Check Zoom in and look at your images at 100% magnification. If

they look good they will print well.

ORIGINAL DISTORTED Corner handles

Go

od

pri

nti

ng

qu

alit

y

Bad

pri

nti

ng

qu

alit

y

QUICK START (cont. )

How to change the template color theme You can easily change the color theme of your poster by going

to the DESIGN menu, click on COLORS, and choose the color

theme of your choice. You can also create your own color

theme.

You can also manually change the color of your background by

going to VIEW > SLIDE MASTER. After you finish working on

the master be sure to go to VIEW > NORMAL to continue

working on your poster.

How to add Text The template comes with a number of pre-

formatted placeholders for headers and

text blocks. You can add more blocks by

copying and pasting the existing ones or by

adding a text box from the HOME menu.

Text size Adjust the size of your text based on how much content you

have to present.

The default template text offers a good starting point. Follow

the conference requirements.

How to add Tables To add a table from scratch go to the INSERT menu

and click on TABLE. A drop-down box will help you

select rows and columns.

You can also copy and a paste a table from Word or another

PowerPoint document. A pasted table may need to be re-

formatted by RIGHT-CLICK > FORMAT SHAPE, TEXT BOX,

Margins.

Graphs / Charts You can simply copy and paste charts and graphs from Excel

or Word. Some reformatting may be required depending on

how the original document has been created.

How to change the column configuration RIGHT-CLICK on the poster background and select LAYOUT to

see the column options available for this template. The

poster columns can also be customized on the Master. VIEW >

MASTER.

How to remove the info bars If you are working in PowerPoint for Windows and have

finished your poster, save as PDF and the bars will not be

included. You can also delete them by going to VIEW >

MASTER. On the Mac adjust the Page-Setup to match the

Page-Setup in PowerPoint before you create a PDF. You can

also delete them from the Slide Master.

Save your work Save your template as a PowerPoint document. For printing,

save as PowerPoint of “Print-quality” PDF.

Print your poster When you are ready to have your poster printed go online to

PosterPresentations.com and click on the “Order Your Poster”

button. Choose the poster type the best suits your needs and

submit your order. If you submit a PowerPoint document you

will be receiving a PDF proof for your approval prior to

printing. If your order is placed and paid for before noon,

Pacific, Monday through Friday, your order will ship out that

same day. Next day, Second day, Third day, and Free Ground

services are offered. Go to PosterPresentations.com for more

information.

Student discounts are available on our Facebook page.

Go to PosterPresentations.com and click on the FB icon.

© 2013 PosterPresentations.com 2117 Fourth Street , Unit C Berkeley CA 94710

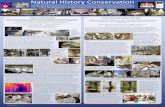

Above: the bones of the right forelimb being consolidated, plotted on the plans and

surveyed-in. Below: left, the upside-down skull has been cleaned, consolidated and

jacketed with acid-free tissue, foil, plaster and hessian with a few wooden splints.

Middle and right, a protective and supporting cage of channelled galvanised steel

‘Unistrut’ was bolted around the skull, re-enforced with thick wooden batons held

in place with plaster & hessian, and with a thick plywood base bolted underneath.

Abstract

Dismantling the Finback Whale skeleton at Cambridge University Museum of Zoology

At 70ft (21m) long, this particular Finback Whale skeleton is one of the biggest known of this species, which

is second in size only to the Blue Whale. This animal was washed ashore dead at Pevensey in Sussex in 1865

and 40,000 people are estimated to have travelled to see it on the beach within the first few days. The

skeleton was prepared and subsequently bought for the museum by public subscription. It used to be

mounted inside but in the 1990s it was hung from a ceiling outside the museum. After 16 years of being

nested in and defecated on by pigeons, the skeleton had to be dismantled and packed away whilst a

refurbishment program gutted the building and created a new glass foyer for the whale to be re-mounted in.

Bespoke wooden crates were made for the baleen and forelimbs, wooden shelving made for the ribs (some up

to 285cm long) and a large shed was constructed especially to house the skull for the duration of the building

project. The main supporting metal beam onto which the vertebrae were threaded was in two main sections,

bolted together. The larger of these weighed in the region of 170Kg and was lowered with a system of pulleys.

Conclusions Both projects presented significant health and safety risks and complex problems that

required solving almost every day. But with good planning well in advance both projects were completed

within the planned timeframes and within budgets. A good photographic, written and video record was made

of each project, and both projects will result in publications. If Unistrut channelling had not been available to

make the rigid protective and supportive cages around the skulls and mandibles in both cases, the projects

would have taken much longer and the bones would have been much more vulnerable and might well have

sustained serious damage. The team looks forward to repeating the Cambridge project - in reverse and at

greater height , but thankfully without pigeon issues - in 2016 or 2017.

Acknowledgements Thanks are due to: the team in Abu Dhabi (Phil Rye, John Stewart, Will Higgs and

the funders Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, ADNOC ) and the team assisting with the skeleton in Cambridge

(Phil Rye, Matt Lowe and various volunteers). With apologies to Charles Dickens for the title of this poster.

This almost complete and only slightly disarticulated skeleton was exposed in a low friable sandy cliff of

sabkah sediments on the edge of a tidal channel in Mussafah on the outskirts of Abu Dhabi City. First, the

overburden had to be removed carefully and the general outline and extent of the bones ascertained. Then

the very fragile bones (with the texture and strength of a digestive biscuit) were excavated, with much of

the sediment kept for environmental analysis including the identification of molluscs, barnacles,

foraminifera and ostracods etc.

In 2009 the partial skeleton of a large 5,200 year-old baleen whale was excavated in coastal sediments in Abu Dhabi (UAE). In 2013 a similar sized (21m long) skeleton of a 150 year-old finback whale that had been suspended from a ceiling for nearly 20 years outside Cambridge University’s Zoology Museum was cleaned, dismantled and moved into temporary storage for the duration of a refurbishment project. In Abu Dhabi the 4m long, 2.3m wide, fragile skull was in a few pieces due to taphonomic processes in the burial environment. In Cambridge the 4.5m long skull was complete and weighed over a tonne.

Despite the whales’ very different contexts and ages and the fact that one skeleton had to be lifted from desert sediments and transported several miles whilst the other skeleton had to be removed from its suspended mount and moved fifty metres, they are both large filter-feeding ‘baleen’ whales (Suborder Mysticeti) and some of the processes used in each of the projects were very similar. The excavated skeleton had to be cleaned and recorded, assessing the sediments and taphonomic processes evident at the site. The displayed skeleton had to be cleaned and the way it was mounted and suspended had to be recorded in detail to facilitate remounting in a couple of years. Interesting pathologies exhibited by the bones were noted in both cases. In particular, both projects necessitated constructing protective and supportive frameworks around the skulls and mandibles, bolting together lengths of galvanised steel ‘Unistrut’ to enable the large and heavy yet fragile specimens to be safely moved with airjacks and cranes.

A Tale of Two Mysticeti

Email: [email protected] Web: wwww.natural-history-conservation.com Mobile: 07973 869613

Affiliated Researcher, Cambridge University Museum of Zoology.

Research Associate (Geology), Norfolk Museums & Archaeology Service.

Nigel R. Larkin BA MSc

Excavating and lifting the 5,200 year-old baleen whale skeleton in Abu Dhabi

Despite the skeleton being cleaned about 10 years previously, the accumulated pigeon faeces were over an

inch deep in places. Therefore before anything was dismantled the whole specimen was cleaned as thoroughly

as possible with a stiff brush and a vacuum cleaner to get rid of the worst of the pigeon droppings and nesting

material as well the general, dust, dirt and cobwebs etc. After being removed from the armature, each bone

was thoroughly dry brushed again before being swabbed with the mild conservation detergent Synpeonic A7 in

water then the surface was cleaned of the detergent by further swabbing with water, whilst being patted dry

frequently with paper towels so the water did not soak in to the bone. The baleen was cleaned very gently

with small soft brushes and a vacuum cleaner, and was not ‘wet cleaned’. All the rusty metalwork was cleaned

with a spinning wire disk clamped to a bench, and then wiped clean with a damp rag, dried, painted and

labelled. Where possible, the metal brackets were re-attached to specimens to keep them in context.

References Stewart J.R., Aspinall, Beech S. M., Fenberg P., Hellyer P., Larkin N.R., Lokier S.W., Marx,

F.G., Meyer M., Miller R., Rainbow P.S., Taylor J.D., Whittaker J.E., Al-Mehsin K. & Strohmenger C.J.

2011.Biotically constrained palaeoenvironmental conditions of a mid-Holocene intertidal lagoon on the

southern shore of the Arabian Gulf: evidence associated with a whale skeleton at Musaffah, Abu Dhabi, UAE.

Quaternary Science Reviews 30 (2011):3675 - 3690.

Each of the bones were carefully cleaned with soft brushes and then plotted on the site plan by surveying-in

points and drawing in the detail by hand. The site is about 5,200 years old (Optically Stimulated

Luminescence and C14 dating were undertaken (Stewart et al, 2011)) and the bones were very brittle,

occasionally cracked and had little or no mechanical strength. Due to their fragile nature the bones had to

be well consolidated and the reversible methacrylate co-polymer Paraloid B72 was applied at 5 to 10% in

acetone. Once this had set, the larger bones and any adhering sediment were then covered with acid-free

tissue paper and aluminium foil, followed by a thick covering of coarse hessian strips saturated with plaster

of Paris to build up a thick protective and supportive jacket. Additional support was given by either wooden

splints or a strong rigid metal frame bolted together around the specimen to which the plaster jackets were

attached with more hessian and plaster so the large bones could be lifted safely and taken to off-site.

Above left, the right dentary of the mandible in the foreground, with the skull

behind (the skeleton is preserved upside-down); middle, the right limb bones in

the foreground (scapula, radius and ulna) with ribs and vertebrae behind; and

right, consolidating the right dentary, with parts of the skull in the foreground.

Above right: Once the skull

was encased securely in its

rigid cage, we had to tunnel

underneath the specimen to

free it from the concreted

sabkah sands on which it

lay, leaving it perched on

pillars of sediment (far

right). The two dentaries of

the mandible were

protected with similar rigid

plaster jackets and cages (right), enabling all three very fragile specimens to be safely lifted on to a flatbed truck with a crane (far

right) and taken to the Environment Agency buildings in Abu Dhabi city centre. None of the cages flexed

but remained incredibly rigid, so the bones were not damaged in the lifting process.

Although the skeleton was a mere 150 years old and still had some strength and

mechanical integrity (unlike the Abu Dhabi whale), the 4.5m-long skull and mandible

were incredibly heavy, estimated at over a ton in weight. To move the skull into

position in the 1990s, it required 19 strong men, and injuries were sustained.

Unfortunately the sutures of the skull are not fused and it had been sawn in half

lengthways when initially prepared, so the whole structure was weaker than it might

have been. Therefore, the skull itself could not support its own weight so a cage of

galvanised steel Unistrut channel was built around it, bolted to a thick plywood base.

This project was challenging in many respects. The daytime temperatures were frequently over 40˚C and the

humidity was always over 90% so both sunburn and heatstroke were a real risk and simply the glare from the

sun and the occasional dust/sand storm posed their own problems. The fragile bones had no mechanical

strength and some were already shattered before excavation commenced (in transpired lorries and bulldozers

had been moving back and forth above the site recently). The bones were like biscuit, hence the need for

plenty of consolidation and the application of rigid protective plaster jackets and, where required, the

construction of incredibly strong and rigid cages of channelled galvanised steel ‘Unistrut’.

The task had to be approached carefully for several reasons: the pigeons had left behind a significant

biohazard (not just their faeces but nesting materials and dead bodies); we would be working at height and

the bones were considerably heavy; it was not clear how all the metal framework was joined together nor

whether the rusty nuts and bolts would be easily undone; and we would be moving large amounts of

materials, tools and equipment up a flight of stairs at the start and end of every day and well as carrying the

large bones down. Because the specimen would need to be re-mounted in a new position in just a couple of

years, meticulous records needed to be made of exactly how it was mounted and the order in which it would

need to be reassembled. Therefore copious photos were taken and notes written, and all the bones and

metalwork were labelled thoroughly before any dismantling commenced. A simple label on a bone saying

what the bone was i.e. ‘rib R15’ was not enough – every hole where a bolt had been inserted was given it’s

own tie-on label describing the piece of armature that it had been bolted to, and the matching bit of

armature was labelled appropriately as well. WD40 was applied to all the nuts and bolts in advance, being

careful not to contaminate the bones. Various parts of the project were videoed and the whole process was

recorded with a time lapse camera (you can now see the video on the zoology museum’s Facebook page).

Far left: initial

cleaning of the

bones with a brush

and ‘Backuum’

cleaner. Middle:

removing

vertebrae from the

metalwork. Right:

cleaning ribs with

Synperonic A7.

The protective cage was designed so that a crane would be able to

lift it using straps place underneath. Once the cage was built and

Plastazote-lined wooden supports screwed securely underneath

the bones, the weight had to be taken off the metal wires it was

suspended from. ‘Airjacks’ were used (strong inflatable rubber

‘pillows’). They were placed underneath the base of the cage to

lift up the whole structure so that the wires could be undone and

the weight transferred. Then a mobile crane moved the skull and

mandible – which together with the metalwork weighed 1.6 tons!

Left: a close-up of the galvanised steel Unistrut

system bolted together. Right, the skull and

mandible about to be moved by a crane.

![[Type text] [Type text] [Type text]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/61ec84b0abca616e814ee6cd/type-text-type-text-type-text.jpg)