A Survey of the Use of Emergency Parenteral Medication at a Secure Psychiatric Hospital

-

Upload

psychforall -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

Transcript of A Survey of the Use of Emergency Parenteral Medication at a Secure Psychiatric Hospital

-

7/28/2019 A Survey of the Use of Emergency Parenteral Medication at a Secure Psychiatric Hospital

1/8

Original Research Article

A survey of the use of emergency parenteral medication at a securepsychiatric hospital

Camilla Haw, Jean Stubbs, Simon Gibbon

St Andrews Healthcare, Northampton, UK

Abstract

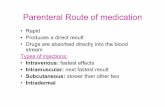

Background: The use of additional sedative psychotropic medication to calm agitated or aggressivepatients is known as rapid tranquillisation (RT). Several studies of RT practice have been conducted in

psychiatric intensive care units (PICUs) and acute psychiatric settings.

Method: We carried out a cross-sectional survey of the use of parental sedation in an English securehospital using data from medication charts and case notes.

Results: We studied the medication charts of 316 patients and found 203 incidents (all involving intra-muscular route) of parenteral sedation involving just 35 patients. The vast majority (30; 85.7%) of thoseadministered parenteral sedation were female and most (23; 65.7%) had emotionally unstable personalitydisorder. The most common indication was self-harm (44; 21.7%). In 24 (11.8%) instances the patient hadrequested an injection. A single drug was administered in 159 (78.3%) cases. The most commonlyadministered drug was lorazepam (152 cases) followed by haloperidol (69) and olanzapine (21). Case notedocumentation was frequently inadequate and in very few cases was there evidence of physical monitoring.

Conclusions: The use of parenteral sedation was rather different from that previously described in PICUs.Hospital policy and NICE guidance were not always being followed. Measures to rectify these deficits arebeing taken.

Keywords

Rapid tranquillisation; antipsychotic; benzodiazepine; secure unit; survey

INTRODUCTION

Aggressive or violent behaviour is one of thecommonest reasons patients are admitted tosecure care (Dolan, 2001; Davies & Oldfield,2009). The short-term management of such

behaviour focuses on non-pharmacologicalinterventions, such as de-escalation, while theuse of restraint, seclusion and sedation areconsidered treatments of last resort. Rapidtranquillisation (RT), or emergency sedation,has been defined as the use of psychotropicmedication to control agitated, threatening ordestructive psychotic behaviour (Pereira et al.2005). The National Institute for ClinicalExcellence (2005) adopted a somewhat broader

Correspondence to: Dr Camilla Haw, Consultant Psychiatrist, St AndrewsHealthcare, Billing Road, Northampton, NN1 5DG. E-mail:[email protected] published online 22 November 2012

Jc NAPICU 2012:9:7784 77

Journal of PsychiatricIntensive Care

Journal of Psychiatric Intensive CareVol.9 No.2:7784doi:10.1017/S1742646412000301Jc NAPICU 2012

-

7/28/2019 A Survey of the Use of Emergency Parenteral Medication at a Secure Psychiatric Hospital

2/8

definition of RT, namely the use of medicationto calm/ lightly sedate the patient, reduce therisk to self and/ or others and achieve anoptimal reduction in agitation and aggression.The NICE Guideline also states that the use ofas required (prn) and one-off (stat) additionaldoses of oral psychotropic medicines should beconsidered as part of RT. The two most commonclasses of drugs used in RT are benzodiazepinesand antipsychotics. Although RT can be areasonably safe procedure, there are concernsabout unwanted side effects of medication,principally dystonia with first generation antipsy-chotics and respiratory depression with benzodia-zepines. Other dangers of RT include neurolepticmalignant syndrome (NMS), needle stick injuriesand injuries to patient and staff during restraint.There is also a small but potentially serious riskwith antipsychotics of cardiac dysrhythmiasleading to sudden death (Ray et al. 2001).

Relatively little research has been conductedto establish the preferred drugs and doses for usein RT, although there have been four pragmaticrandomised controlled trials (RCTs) of intra-muscular medication in real-life violent oragitated patients, known as the TREC studies(see for example TREC Collaborative Group,2003; Alexander et al. 2004). A systematicreview of guidelines and phase III RCTs ofmedication used for rapid tranquillisation,identified only 20 RCTs and concluded therewas a lack of high quality clinical trials availableand that no particular medication regime forRT could definitively be recommended overothers (Pratt et al. 2008). Similarly, the NICEGuideline (National Institute for Clinical Excel-lence, 2005) states that there are no conclusivebenefits in terms of effectiveness of oneantipsychotic over another, of antipsychoticsover benzodiazepines or of combination med-

ications over single medication regimes. TheRT policy of our own hospital that was currentat the time of this study recommended theuse of lorazepam 2 mg IM and/or haloperidol510 mg IM or alternatively olanzapine IM.No mention was made of the use of sedativeantihistamines. Prescribers were also advised torefer to the algorithm for RT in the currentedition of the Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines.The Hospitals RT policy recommended the

IM over the IV route on the grounds of safetybut did not preclude the use of IV sedation.

Surveys of the use of psychotropic medicationfor RT have focused upon general acutepsychiatric wards and psychiatric intensive careunits (PICUs; see for example Pilowsky et al.1992; Brown et al. 2010). We could find only asmall literature on emergency parental sedationfor patients in low and medium secure care anddecided to carry out a cross-sectional audit atour own hospital in order to review local clinicaland risk management protocols around RT.A further rationale for the survey was that RT is,at present, a topical issue.

The primary aims of the study were to surveythe nature, timing and frequency with whichintramuscular (IM) or intra-venous (IV) seda-tion was given to male and female patients at alarge secure (mixture of medium and low secureprovision) psychiatric hospital. Secondary aimswere to establish the main reasons for admin-istering such sedation, whether or not the localpolicy was being adhered to and whether or notthere was evidence that patients were beingmonitored after being given sedation.

METHOD

Setting

St Andrews Healthcare, Northampton, is a largesecure psychiatric hospital caring for patientsof a wide variety of ages, many of whom havecomplex mental health needs and exhibitchallenging behaviour. Although the hospital isa charity, almost all patients are funded by theNHS. The study was conducted among themale and female forensic and rehabilitation

services which comprise a total of 414 beds(275, 66% male; 139, 34% female) in 26 wards(11 medium secure, 10 low secure, 3 locked and2 open units). At the time of conducting thissurvey there was no psychiatric intensive careunit (PICU). The majority of male patientssuffer from schizophrenia and related psychoseswhile the most common diagnoses for femalepatients are emotionally unstable personalitydisorder followed by schizophrenia. Co-morbidity

Haw C et al.

Jc NAPICU 2012:9:778478

-

7/28/2019 A Survey of the Use of Emergency Parenteral Medication at a Secure Psychiatric Hospital

3/8

of psychiatric disorders is common. Four unitscater for older adults; the rest are for patients ofworking age and five units are for patients withmild learning disabilities and co-morbid mentaldisorders and/or challenging behaviour. One23-bed unit is dedicated to the treatment offemale patients with emotionally unstable per-sonality disorder using dialectical behaviourtherapy. All medium secure units have seclusionrooms, as do four of the low secure units, butnone of the locked or open units have them.

Hospital RT policy

The hospital policy current at the time of thestudy defined RT as the emergency adminis-tration of IM or IV tranquillising/ sedative

medication in order to calm a patient andprevent them from being violent towards self,other people or property. Thus, oral medica-tion was not included in the definition (thepolicy has since been changed and now includesoral drugs). Medication may be as required orwritten as a one-off (stat) dose and must beprescribed by a doctor. Following the adminis-tration of RT the nurse must sign the admin-istration box on the paper medication chart,complete an electronic RT form (this describesthe reason for giving the RT, its timing, the

drug(s) given and by whom), make an entry inthe patients progress notes and carry outmonitoring of vital signs and level of conscious-ness at intervals as agreed with the doctor butusually every 15 minutes following RT. If thepatient is uncooperative with monitoring thisshould be recorded in the patients notes.

Data collection

Approval for the study was granted by the

hospital audit committee. The wards werevisited in November and December 2011. Allcurrent medication charts (a chart can contain amaximum of three months of prescriptions)were scrutinised and details of any antipsychotic,anxiolytic or other sedative medication suchas promethazine and administered IM or IV(excluding depot antipsychotics) were recordedon a paper data entry form (one form was com-pleted for each injection of sedation administered).

Consent to treatment forms T2, T3 and Section62 were checked to see that the sedation hadbeen authorised. (Under the Mental Health Act1983 (amended in 2007) of England and Wales,detained patients beyond the first three monthsof treatment have to have their psychotropicmedication authorised on a form T2 or T3. If apatient gives informed consent to treatmenta form T2 is completed by their responsibleclinician. If they either refuse the treatment orare not capable of consenting then a secondopinion appointed doctor authorises the treat-ment on a form T3. Urgent medical treatmentcan be authorised on a Section 62.) The auditorsalso checked to see if there were any physicalobservation charts recording patients pulse,blood pressure, respiratory rate, level of con-sciousness and blood oxygen saturation on theward. Patients electronic notes were examinedto check that the administration of sedationhad been documented as per hospital policy,whether or not the patient was documented ashaving been restrained or secluded and whetheror not there was evidence of physical monitor-ing of the patient, including level of conscious-ness or a statement that the patient was refusingphysical monitoring. Basic demographic andclinical details were collected from the case noteson all patients who received IM or IV sedation.Anonymised data were entered into SPSS (2009)and subjected to descriptive analyses.

RESULTS

A total of 316 medication charts were examinedbelonging to 195 male and 121 female patients.There were 203 IM but no IV sedativeinjections recorded as being administered to atotal of 35 patients. These 35 patients received amedian of four injections (range 123). Ten IM

injections (IMIs) were given on the four maleadmission wards and 145 on the three femaleadmission wards. A further 35 IMIs were adminis-tered on a low secure ward for older femalepatients. The remaining 13 IMIs were spread acrossa number of rehabilitation wards. No IMIs weregiven on the two wards for older male patientsand none on the ward dedicated to thetreatment of female patients with emotionallyunstable personality disorder.

A survey of the use of emergency parenteral medication at a secure psychiatric hospital

Jc NAPICU 2012:9:7784 79

-

7/28/2019 A Survey of the Use of Emergency Parenteral Medication at a Secure Psychiatric Hospital

4/8

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of the 35 patients who receivedIM sedation are presented in Table 1. Patients werepredominantly female, had a primary diagnosis ofemotionally unstable personality disorder andtended to be given IM sedation relatively earlyon in their hospital stay (median duration of stayat St Andrews is currently just over two years).

Timing of IM sedation

Between Monday and Friday the mean dailynumber of IMIs was 30.8, whereas at theweekend it was lower at 24.5. As would beexpected, almost all IMIs were given during thedaytime, the peak time being between 12 noonand 8pm. There was no increase at patient meal

times or at nursing handover times. For thosepatients who received a large number of IMIsthere appeared to be some clustering of injectionsover the course of a number of days.

Nature and dosages of drugs administered

A single drug was administered in 159 (78.3%)cases. In the remaining 44 (21.7%) instances

haloperidol and lorazepam had been adminis-tered as separate injections at the same point intime. No drug dosages exceeded the BritishNational Formulary (Joint Formulary Commit-tee, 2011) recommended limits but we did nottake into account patients usual regular doses ofmedication. By far the most frequently adminis-

tered drug was lorazepam (152 cases), followedby haloperidol (69), olanzapine (21), zuclo-penthixol acetate (4) and promethazine (1).Details of the drugs administered are given inTable 2. Only 3 (1.5%) patients had a secondinjection of sedative medication administeredwithin two hours of the first dose. In 197(97.0%) of cases the drug(s) administered werealready prescribed in the prn section of themedication chart. In five (2.5%) cases the doctor

Table 1. Characteristics of patients given parenteral sedation (N535)

Patient characteristic No. (%)

Female gender 30 (85.7)

Security level

Medium secure 25 (71.4)Low secure or locked 10 (28.6)

Legal status

Section 3 20 (57.1)

Restricted 11 (31.4)

Other court sections 4 (11.4)

ICD-10 clinical diagnoses*

Emotionally unstable personality disorder 23 (65.7)

Schizophrenia and related psychoses 11 (31.4)

Mild learning disabilities 12 (34.3)

Substance misuse 5 (14.3)

Other personality disorders 4 (11.4)

Other diagnoses 6 (17.1)

Age in years Median 32 (range 1852)

Length of stay at St Andrews in years Median 0.8 (range 0.26.9)

Number of injections of IM medication Median 3 (range 124)

*Some patients had more than one diagnosis

Table 2. Details of parenteral sedation administered (N5203)

Drug(s) administered Number of doses (%)

Lorazepam 108 (53.2)

Lorazepam1Haloperidol 44 (21.7)

Haloperidol 25 (12.3)

Olanzapine 21 (10.3)Zuclopenthixol acetate 4 (2.0)

Promethazine 1 (0.5)

Haw C et al.

Jc NAPICU 2012:9:778480

-

7/28/2019 A Survey of the Use of Emergency Parenteral Medication at a Secure Psychiatric Hospital

5/8

came to the ward to prescribe the medicationand in one case a doctor gave a verbal messagefor a drug to be given.

Indications for IM sedation

In 37.4% of cases there was no documentedreason for the IMI (see Table 3). In some of thesecases the patient was described as calm or settledprior to the injection of RT medicine. In othercases there was no description of the patientsbehaviour. The most common reason given wasself-harm, followed by violence towards personsand generally disturbed behaviour.

Case note documentation

For 53 (26.1%) cases there was no case notedocumentation that an IM dose of medicationhad been given. In 139 (68.5%) cases there wasdocumentation in the progress notes giving thetiming, name, route and dose of the IMI but inonly 58 (28.6%) cases was the required rapidtranquillisation event form completed.

Consent to treatment status

All 35 patients were detained under the MentalHealth Act 1983 (amended in 2007) of Englandand Wales and all but one were beyond the firstthree months of treatment on their section. Thisone patient had received 16 IMIs, which havebeen excluded from the following analysis asforms T2 and T3 were not yet applicable. Most(94/187; 50.3%) doses of IM sedation wereauthorised by a form T3; 26 (13.9%) doses were

authorised by a form T2; and 34 (18.2%) doseswere not authorised by the current consent totreatment certificate. A total of 23 (11.3%) doseswere given under the provision of Section 62.For ten IMIs no consent to treatment formswere found with the medication charts forthe two patients concerned. Interestingly, therewere 24 (11.8%) instances (all involvingdetained female patients) where the patientwas recorded as requesting IM sedation.

Use of other treatments for therapeuticcontainment

In 83 (40.9%) cases it was documented thatthe patient was restrained and in 20 (9.9%) casesit was documented that the patient was also

secluded.

Post-RT monitoring

In only 5 (2.5%) cases were readings of pulse,blood pressure and respiratory rate recorded.There was only one instance where a pulseoximeter had been used. In only 2 (1.0%) caseswas it documented that the patient refused to bemonitored.

DISCUSSION

In this study of male and female patients at asecure hospital, the administration of IM sedationappeared common among female patients witha diagnosis of emotionally unstable personalitydisorder, especially those on female mediumsecure admission wards. A small number ofpatients received a large number of IMIs. Themost common indication for IM sedation wasself-harm and a minority of patients even

requested an injection. In another study ofaggressive incidents conducted in a specialhospital, a small number of female patients wereresponsible for the majority of incidents requiringemergency sedation (Tuddenham & Logan, 2005).This is in contrast to emergency prescribingin general psychiatric hospitals and PICUs wherethe majority of patients receiving IM sedationare male, have psychosis and are aggressive(Pilowsky et al. 1992; Brown et al. 2010).

Table 3. Documented indications for parenteral sedation (N5203)

Indication No. (%)

No reason documented in case notes 76 (37.4)

Self-harm 44 (21.7)

Violence towards persons 28 (13.8)

Generally disturbed behaviour 16 (7.9)

Threats of violence 12 (5.9)

Agitation 12 (5.9)

Threats of self harm 8 (3.9)

Destruction of property 6 (3.0)

In order to take a blood sample 1 (0.5)

A survey of the use of emergency parenteral medication at a secure psychiatric hospital

Jc NAPICU 2012:9:7784 81

-

7/28/2019 A Survey of the Use of Emergency Parenteral Medication at a Secure Psychiatric Hospital

6/8

Another finding of our study was that themajority of patients given IM sedation weredetained on civil as opposed to court sections.This was also the case in a study conducted in aregional secure unit (McLaren et al. 1990).

No doses of sedation were given by theIV route (the hospitals RT policy states theIM route is preferred to IV on safety grounds),again in contrast to an older study of emergencyprescribing in a general psychiatric hospitalwhere IV sedation was favoured over theIM route (Pilowsky et al. 1992). In a recentstudy of RT in seven PICUs no sedation wasgiven by the IV route (Brown et al. 2010). Thiswas also a finding in a study of medication givenfor aggressive incidents in a special hospital(Tuddenham & Logan, 2005), suggesting thatclinicians have now abandoned the IV route.There are a number of possible reasons for themove to IM sedation including ease of admin-istration, that nursing staff can administer thedrug and on the grounds of safety.

In this study, lorazepam 2 mg was themost common sedative administered, sometimesgiven concurrently with haloperidol 5 mg.Clinicians are known to favour benzodiazepinesover antipsychotics for neuroleptic navepatients, though preferring the combination ofan antipsychotic with a benzodiazepine or justan antipsychotic for non-nave patients (Pereiraet al. 2005). Expert opinion favours benzodia-zepines as the mainstay of RT (McAllister-Williams & Ferrier, 2002). The most commonlyused antipsychotic was haloperidol, despite thefact that this drug has been found to be poorlytolerated when used for RT (Huf et al. 2007),the summary of product characteristics (SPC)recommends a pre-treatment ECG and theMaudsley Prescribing Guidelines state that IM

haloperidol should be the last drug consideredfor IM RT (Taylor et al. 2012). The use of IMhaloperidol is not favoured by other expertopinion (McAllister-Williams & Ferrier, 2002),though the TREC studies found some positiveevidence of efficacy (Alexander et al. 2004).The NICE Clinical Guideline on schizophrenia(National Institute for Health and ClinicalExcellence, 2009) states that all psychiatricinpatients should have an ECG prior to any

antipsychotic. Only occasional use was made ofthe second generation antipsychotic, olanzapine,despite its low rate of extra-pyramidal sideeffects and lack of significant QTc prolongation(McAllister-Williams & Ferrier, 2002) and nouse was made of IM aripiprazole, the othersecond generation antipsychotic available as ashort-acting IM preparation. The limited use ofIM olanzapine may relate to its interaction withparenteral benzodiazepines which may result inexcessive sedation, cardiorespiratory depressionand death. Only one patient received prometha-zine even though this drug is considered a usefuloption in patients who are tolerant of benzo-diazepines (Taylor et al. 2012), and the fact thatthis sedative antihistamine is licensed for seda-tion (see the SPC) for parenteral promethazine,www.medicines.org.uk). Very few patientsreceived more than one injection of sedation,unlike in previous studies of RT (Pilowsky et al.1992; Brown et al. 2010). This may be the resultof different patient populations in these studies.In our study many patients were female and hada primary diagnosis of borderline personalitydisorder, in contrast to other studies where malepatients with psychosis predominated. In ourstudy, four patients received zuclopenthixolacetate. This preparation is not suitable for RTbecause its action is not rapid (sedation usually

begins to be seen two hours post injection(Taylor et al. 2012)). Very few patients receiveda second IMI within two hours of the first.Clearly, it is necessary to allow sufficient timefor medication to take effect. The MaudsleyPrescribing Guidelines recommend only repeat-ing the IMI after 3060 minutes have elapsed ifthere is insufficient effect (Taylor et al. 2012).

In the current study, case note documentationwas minimal and there was negligible docu-mented physical monitoring of patients post-

IMI, despite the NICE RT guidance. In onlya quarter of cases had hospital policy had beenfollowed and an RT event form been com-pleted. Although we did not systematically studythe comments of nursing staff about patientsbehaviour post-injection, in only a smallproportion of cases was the patients levelof consciousness described. Previous studiesof RT have not examined the associated casenote documentation. However, in a survey of

Haw C et al.

Jc NAPICU 2012:9:778482

-

7/28/2019 A Survey of the Use of Emergency Parenteral Medication at a Secure Psychiatric Hospital

7/8

UK consultant psychiatrists concerning thetreatment of acute behavioural disturbance, only9% said they did not routinely perform routinephysical observations post RT (Pereira et al.2005). There are, of course, difficulties inattempting to physically monitor patients withaggressive and challenging behaviour. Wherepatients have been secluded but are stillambulant, nursing staff are placing themselvesat risk of assault by entering the seclusion roomin order to perform physical observations.However, the assessment of sedation, respiratoryrate and general physical status can be done froma distance and does not require nursing staff toenter the seclusion room.

We noted in our survey that consent totreatment forms did not always authorise theIMI and sometimes IM sedation was adminis-tered under restraint to patients being treatedon a form T2. It would seem unlikely that apatient requiring restraint for an IMI could begiving informed consent for a sedative injection.We searched the case notes, including careplans, of these patients to see if they had madean advance statement that they wished toreceive IM sedation should they become acutelyunwell. However, no such statements couldbe found. A further problem was that a copy of

the consent to treatment form was not alwayswith the medication chart. The above aresignificant shortcomings that need to be rectifiedand re-audited.

We found a minority of patients whorequested IM sedation rather than receive anoral dose of sedation. In a previous study,conducted in male and female forensic patientsat our hospital, some patients commented thatthe IM route was preferred because of its morerapid onset and greater efficacy and duration of

effect (Haw et al. 2011). But is it ethical toadminister IM sedation on request? The oralroute is to be preferred on the grounds of safetyand when a patient suffering from an emotion-ally unstable personality disorder requests anIMI, administering one could be viewed asfeeding their wish to punish themselves.

Our study has a number of limitationsincluding its retrospective and cross-sectional

design which prevented us from carrying out adetailed study of the timing of IM sedation toindividual patients over days and weeks. We didnot examine concurrent (regular) medicines anddoses and so it was not possible to assess if theseIM doses pushed the patients total antipsychoticdoses beyond a total percentage dose of 100%.A further limitation is that we did not havepsychiatric diagnoses for all the inpatientscurrent at the time of the survey and so wereunable to make statistical comparisons betweenthose patients who did and those who did notreceive IM sedation. We have used the termsedation rather than RT in describing ourstudy. This is because we cannot be sure that alldoses met the definition of RT given in thehospitals policy. Some doses might be betterdescribed as the giving of prn sedation. Wewere unable to discriminate between these twoscenarios because of the retrospective natureof the study design. In practice RT is not aclear-cut phenomenon, there are differingopinions as to its definition and there is overlapwith prn doses. However, it can be arguedthat all patients receiving parenteral sedationshould be physically monitored post-injectionregardless of the circumstances leading to theadministration of an IMI. We only studiedparenteral medication. RT does, of course,include the administration of oral sedation andhospital policy now reflects this fact.

In conclusion, emergency parenteral medica-tion was administered to a relatively smallnumber of predominantly female patients manyof whom were on medium secure wards. Intra-muscular lorazepam was the drug given inthe majority of cases and first generationantipsychotics were favoured over second gen-eration ones. Case note documentation of therationale for administration of sedation and

physical health observations after IMI showedroom for significant improvement and not allmedication was authorised by consent to treat-ment forms. Hospital policy was rarely beingfollowed and a worryingly small percentage ofpatients underwent any physical monitoring afterIM sedation. These results have implicationsfor staff training and policy awareness in orderto optimise patient safety and compliance withlegal requirements. Our hospital is now running

A survey of the use of emergency parenteral medication at a secure psychiatric hospital

Jc NAPICU 2012:9:7784 83

-

7/28/2019 A Survey of the Use of Emergency Parenteral Medication at a Secure Psychiatric Hospital

8/8

Safe Medicines Administration courses for nur-sing staff, there is a regular audit of compliancewith consent to treatment documentation andthere are plans for pharmacists to hold trainingsessions on RT for all clinical staff, particularly onthose wards where IM sedation is used frequently.We plan to repeat the audit at a later date to see ifdocumentation has improved.

References

Alexander, J., Tharyan, P., Adams, C., John, T., Mol, C.

and Philip, J. (2004) Rapid tranquillisation of violent or

agitated patients in a psychiatric emergency setting. British

Journal of Psychiatry. 185: 6369.

Brown, S., Chhina, N. and Dye, S. (2010) Use of

psychotropic medication in seven English psychiatric

intensive care units. The Psychiatrist. 34: 130135.

Davies, J. and Oldfield, K. (2009) Treatment need and

provision in medium secure care. British Journal of Forensic

Practice. 11: 2431.

Dolan, M. (2001) Characteristics and outcomes of patients

admitted to a psychiatric intensive care unit in a medium

secure unit. The Psychiatrist. 25: 296299.

Haw, C., Stubbs, J., Bickle, A. and Stewart, I. (2011)

Coercive treatments in forensic psychiatry: a study of patients

experiences and preferences. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and

Psychology. 22: 564585.

Huf, G., Coutinho, E.S.F. and Adams, C.E. (2007)

Rapid tranquillisation in psychiatric emergency settings in

Brazil: pragmatic randomised controlled trial of intramuscularhaloperidol versus intramuscular haloperidol plus

promethazine. BMJ. 335: 869.

Joint Formulary Committee (2011) British National Formulary,

62nd ed. London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press.

McAllister-Williams, R.H. and Ferrier, I.N. (2002)

Rapid tranquillisation: time for a reappraisal of options

for parenteral therapy. British Journal of Psychiatry. 180:

485489.

McLaren, S., Browne, F.W.A. and Taylor, P.J. (1990)

A study of psychotropic medication given as required in a

regional secure unit. British Journal of Psychiatry. 156: 732735.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2005) Violence:

The short term management of disturbed and violent behaviour in

inpatient psychiatric settings and emergency departments. Clinical

Guideline 25. London: NICE, 83 pp.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

(2009) Schizophrenia: Core interventions in the treatment and

management of schizophrenia in adults in primary and secondary

care. Clinical Guideline 82. London: NICE.

Pereira, S., Paton, C., Walkert, L.M., Shaw, S., Gray, R.

and Wildgust, H. (2005) Treatment of acute behavioural

disturbance: a UK national survey of rapid tranquillisation.

Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care. 1(2): 8488.

Pilowsky, L.S., Ring, H., Shine, P.J., Battersby, M. and

Lader, M. (1992) Rapid tranquillisation: a survey of

emergency prescribing in a general psychiatric hospital.

British Journal of Psychiatry. 160: 831835.

Pratt, J.P., Chandler-Oatts, J., Nelstrop, L., Branford, D.

and Pereira, S. (2008) Establishing gold standard approaches

to rapid tranquillisation: a review and discussion of the

evidence on the safety and efficacy of medications currently

used. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care. 4: 4357.

Ray, W.A., Meredith, S., Thapa, P.B., Meador, K.G.,

Hall, K. and Murray, K.T. (2001) Antipsychotics and the

risk of sudden cardiac death. Archives of General Psychiatry.

58(12): 11611167.

SPSS (2009) PASW for Windows Release 18.0. Chicago: SPSS

Inc.

Taylor, D., Paton, C. and Kapur, S. (2012) The Maudsley

Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry, 11th ed. Chichester:Wiley-Blackwell.

TREC Collaborative Group (2003) Rapid tranquillisation for

agitated patients in emergency psychiatric patient rooms: a

randomised trial of midazolam versus haloperidol plus

promethazine. British Medical Journal. 327: 708711.

Tuddenham, L. and Logan, J. (2005) Psychotropic drugs

given for aggressive incidents in a special hospital. Journal of

Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology. 16: 8591.

Haw C et al.

Jc NAPICU 2012:9:778484