A STATE PERSPECTIVE ON SPECIAL EDUCATION · the multiply handicapped, the severely handi ... with...

Transcript of A STATE PERSPECTIVE ON SPECIAL EDUCATION · the multiply handicapped, the severely handi ... with...

A STATE PERSPECTIVE ON SPECIAL EDUCATION

Hatsuko Kawahara

The maintenance and progress of a free society demands a system of education which will equip each individual for a lifetime of seeking and applying knowledge to deal effectively with the world, and which will assist each individual in personal development and growth.

To meet this goal, all children and youth in Hawaii are entitled equally to free, quality, public education. No child may be deprived of such educational opportunity because of conditions created through trauma, illness, accidents of inheritance or birth, or social, economic and emotional deprivations. For those children whose needs require additional efforts and resources from the educational system, the State of Hawaii has committed itself to undertake the provision of special education and services.

An Historical Perspective In 1949, Hawaii formalized this commitment

through Act 29, which called for equal educational opportunities for exceptional children. The Act mandated the Department of Instruction, in cooperation with the Department of Health, to establish programs for a[[ exceptional students 20 years of age and under. $100,000 was appropriated to set up classes for the first group of trainable menta[[y retarded students in the regular schools. Prior to this Act, classes were established under the terms "opportunity classes" and "adjustment classes" for slow learners and the students whom we currently refer to as educable mentally retarded. During the period of 1953-1955, the Director, with the assistance of the Department of Health, the Commission of Children and Youth, and the Association to help Parents of the Retarded, clearly defined the target population of the trainable mentally retarded and the educable mentally retarded, thereby differentiating them from the slow-learner students and students with adjustment problems.

Special education programs during the 1950's included students with mental retardation, and students with physical handicaps such as deafness, blindness and crippling conditions. Programs in the regular schools were confined to classes for the mentally retarded and the emotionally disturbed.

4

No student was admitted into special education programs unless he or she was evaluated by the Department of Health, Division of Crippled Children Services or the Division of Mental Health Services.

During the early period of the GO's, when it was recognized that there were students who were handicapped in learning due to neurological impairment, classes were established for children who were evaluated and diagnosed by the Department of Health clinic for children with minimal neurological dysfunction. Until the middle of the GO's, placement of students in special education programs was centralized in the Territorial Department of Instruction's central office.

In 1965, when Oahu established four school districts, the supervision of programs in health, guidance and special education was decentralized. The establishment of classes, selection of personnel, and identification and placement of exceptional children was transferred to all the school districts. It was further decentralized when special schools were transferred to Honolulu and Windward district offices.

During the SO's and early GO's, research studies did not show any significant differences in the improvement of academic ski[[s between the students placed in special education classes and those who remained in regular classes. The largest gains made in the special classes were in social adjustment; educators, therefore, began to question whether segregation of students in special education met the needs of a[[ handicapped students. Results from studies related to job placement of students in special education were too meager to confirm the belief that the public school system can develop special education programs which meet the life goals of the handicapped individual. This periqd was fo[[owed by the enactment of the Elementary and Secondary Act in 1965 which provided funds for the students from economically deprived areas, and focused the national attention on the problems of identification and placement of students in special education. Among them were the "six~hour retarded child," and the child with bilingual problems. The problem

of the use of culturally biased tests for evaluation, and the whole problem of special education's attempt to interface with regular education, gave impetus to the growth of the education of the disadvantaged, apart from the education of the handicapped.

The movement from the medical diagnosis approach to the educational diagnosis approach in the evaluation of students; federal funds to innovate individualized instruction in regular education; collective bargaining attempts to reduce class size in regular education from 35 to 25, so that indMdual needs are met in regular classes; and the recognition by the special and regular educators that if a mildly handicapped child can be kept in the regular classroom setting the problems of the stigma attached to labeling can be prevented-these concepts have had a tremendous impact upon the changing role of special education in Hawaii.

The Department of Education has, throughout the state, established a program of continuous services, of special schools, integrated classes, itinerant services, resource rooms, child study teams and changes in delivery of services. In regular education, experiments with teaching strategies such as precision teaching, resource-room teaching, behavior-modification t~aching techniques, reinforcement learning, programmed instruction and computer-based assist instruction have been attempted in individual schools throughout the state. These experiments and attempts to innovate were an effort to meet the increasing needs of students who were unable to succeed in our public education programs.

The State of Texas has adopted the philosophy that all education should be special education; each child is unique, therefore traditional labels are no longer suitable. They believe exceptional children are seen as more alike than different from other children. We, on the other hand, have moved ahead in general education by introducing individualized instruction, reduced class size, experimentation with HEP materials, three-on-two, team teaching and prescri_~tive teaching, in regular classes, with the hope that rather than special education for all children, we may have regular education for all mildly handicapped students who can be in the mainstream of education.

If this is the goal for the mildly handicapped students who as adults wilt be part of the mainstream in society and in the community, then who are the exceptional students in the public school system in Hawaii? The problems and difficulties in

special education are not so much that it is a dumping ground, but how "Special Education" is to define its scope of services and programs. When classes were large and when the teaching personnel's training, experience or temperament was (and still is in some instances) limited in competency or skill to cope with a student's inability to learn in a regular class, the natural tendency to feel special education could meet the needs of the student was understandable. However, whether this is the best solution for the education of all students who cannot achieve in regular education is not only an issue but questionable.

CHART 1. SPECIAL EDUCATION CLASSES

Exceptional Children (Handicapped)

Description Children whose individual deviations require clinical diagnosis, special equipment, facilities, special techniques and services of highly trained specialists.

Causes Handicapped conditions which may be for life or for indefinite periods. May be organic, trauma, or due to unknown factor.

Programs

Categorization for Administrative Purposes

1. Differentiated curriculum. 2. Specialized techniques for

developing perception, mobility and sensory learning, special equipment, facilities and arrangements.

3. Remedial instruction, educational therapy and specialized counseling services.

1. Mental Retardation 2. Seriously Emotionally

Disturbed 3. Specific Learning Disabili-

ties 4. Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing 5. Visually Handicapped 6. Crippled 7. Chronically HI 8. Speech Impaired

5

CHART 2 REGULAR EDUCATION CLASSES-MAINSTREAM

Children with Learning Difficulties

Description Children who are unable to succeed in general education unless provided with ancillary services such as counseling, individualized instruction, tutoring and remedial education.

Causes

Programs

Categorization for Administrative Purposes

Environmental conditions such as: 1. Deprived conditions due to

poverty. 2. Unhealthy physical or

mental environment. 3. Poor family or social

relationships. 4. Crisis situations. 5. lrrevelant curriculum or

teaching techniques. 6. Transient population. 7. Parental and cultural

pressures.

Modified or adjusted educational programs, remedial reading, computation and communication skills, extra curricular activities. 1. Compensatory education

students 2. Disadvantaged students 3. School dropouts 4. Six-hour retarded child* 5. Pseudo retardation 6. Children with emotional

problems 7. Children with behavioral

disorders •~ome public school systems include these students under exceptional children.

The State's Directions for the 70's We are now in the 70's moving forward to limit

the target population for special education to what we call exceptional children whose life goals, objectives and options are restricted due to their handicapping conditions. It is a target population

6

confined to probably between 6% to 6.5% of the total student population. It is not the 10, 15, 20, or 30% of students who have learning problems which require ancillary services such as counseling, tutoring and remedial education. Chart 1 illustrates the target population for special education.

This means, the target population will consist of the multiply handicapped, the severely handicapped, and the moderately handicapped individual who may need special services throughout his lifetime. If this is the movement in special education, then the challenges to meet the learning problems of the remaining target population of 15 to 20% will be the problem of regular education (see chart 2). A decision must therefore be made to train all regular teachers in remedial techniques, perceptual training, screening, and diagnostic teaching methods. This has significant implications for the in-service and pre-service training of regular teachers. Until this can be accomplished, remedial teachers and resource rooms will continue. It is recognized now, nationally, that the resource room is a program set up for this transitional period.

The long range goal for the school principal is to eliminate the need for a resource room in special education. This means that a particular school may expect to reach the goal of individualized and prescribed teaching within the next 5 to 10 years, meeting the needs of every child in the school in a regular class room setting of 25 to 26 students. Then this particular school may have a special education class for the severely emotionally disturbed child, a trainable class for the retarded, a class for the neurologically impaired, and may have students with impaired hearing in special classes with off-ratio teachers.

For the secondary schools, this will mean iJinerant or support services to regular classes and the establishment of planned occupational training progi:_ams which produce marketable skills. However, the need in a district for a special occupational training center or a special vocational school for ages 12 to 20 may arise if regular schools do not have the facilities or the personnel to meet the vocational or career aspirations of the handicapped students.

The pendulum which swung from the medically diagnosed handicapped students of the early SO's to the education- and behavior-oriented diagnosis of the late 60's, is moving back to the center. For the comprehensively-diagnosed handicapped child, training will not be confined merely to remedial training, visual, motor and auditory perceptual training, but will encompass a training program

focussed on life goals of a career occupation. The goal may be complete independence or partial dependence while functioning in a sheltered environment. The 70's will be the period of the right to education for all handicapped children; a time when the mildly handicapped .can. be.in.the mainstream, making room for the truly exceptional child who may be multiply or severely handicapped and who heretofore could not be enrolled in the public school system. The speed with which we reach this goal will depend upon h'ow rapidly other programs -regular education, compensatory education, and other special programs-can improve and move a~ead.

In education, as in life, we cannot live in isolation and grow; we shall need to interact, share and cooperate with all other programs. However, in so doing, let us not make the mistake of ignoring accountability and responsibility for the assigned target population. We need all the knowledge, techniques, and skills we can acquire in our preparation to meet the varying individual needs of students. We cannot feel secure in the 70's that any single technique, method, material or piece of equipment will help solve the learning problems of children.

Some children will require highly specialized help not available in any setting but a special class; others, even within the same category, may be able

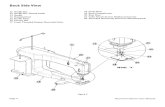

CHART 3 ORGANIZATION Of DELIVERY OF

INSTRUCTIONAL SERVICES TO STUDENTS

STI.IOENTS PL,.ClO IN SPICIM IOUO, TION CL,.SSlS INT!GRA TIO IN RIGUV.R

PROGR,.MS IOR "RT. PHYSICAL IOUCATION. PR,.C TI CM "RTS. ITC

ST DINTS PLACED IN REGU LAR CLASSES PROVIOID WITH ITINERANT SERVICES OR

RESOURCE ROOM SIRVICIS

STI. OINIS PLACID IVITH RI GI.ILAR flA(HERS WITH SLPPORT SERVICCS-SPICIAL MA TERl,.LS "ND

EQUIPMENT

Sl'UOENTS PLACED IN REGL LAR Cl.MSES WITH REGULAR !OUC,.TION TE"CHERS WIT H NO SPECI AL "SSIS1"NCI REQUIR!O

to function well in general education. The degree of impairment will generally determine the nature of the educational program and the setting for the program. This will vary from child to child as well as for each child as he or she progresses in education. It is therefore sometimes more useful when speaking of children who are handicapped to refer to mild, moderate, or severe handicapping conditions, while keeping in mind the appropriate techniques and materials which address each child's unique, special needs. Chart 3 details the delivery of instructional services to students.

In August of 1973 the Management Analysis Center, Inc., under the direction of William Hartman and Graeme Taylor, was hired through the use of Title VI Administration Funds to work with the Special Education Branch of the Hawaii State Department of Education, to assist in developing the State Plan for Special Education.

Three factors contributed to the necessity for developing such a plan: 1) With the acceptance of the Master Plan, the DOE was mandated to develop a State Plan for Special Education. 2) In an effort to assure every handicapped child educational opportunities, the federal government has made such a plan a necessary prerequisite for federal funding eligibility. 3) Since the decentralization which occurred in 1965 in the DOE, guidelines have been necessary for the districts to continue to operate under a single unified school system, while maintaining their independent authority; the guidelines within the plan would help assure that every child in each district would receive a quality education.

Over the past year the Hawaii State Plan for Special Education has been developed within the organization detailed in chart 4. While it would be an obvious impossibility to summarize completely the document, the following may illustrate the important goals specified by the State Plan.

State Plan Special Education Goals Our ultimate goal in special education is to provide

an educational program which will enable all handicapped children to become self-sufficient to the extent their handicaps permit, to enable them to realize their fullest potentials, to acquire selfconfidence and personal dignity and to become contributing members in their families and society.

In order to achieve this goal, special education is dedicated to the development and provision of programs and services which will: 1. Identify, as early as possible, children with handicapping conditions, and evaluate the educational needs of such children.

7

CHART 4 ORGANIZATION FOR DEVELOPMENT OF THE STATE PLAN FOR SPECIAL EDUCATION

Community Advisory Joint Section on

Polic:y Input & Guidance Board of Education Superi ntendent Deputy Superintendent Assistant Superintendents

Special Education, Health and Community Services Council for Hawaii, Consumers

,----C-o_m_m_i_tte- e-------~-,~.-------------------~

Profession.al Advisory

Direct Assistance (State) General Education Branch

- Early Childhood

UH Consultants Special Consultants ,,.. Inter-agency School Health L_..._------

Committee

Pl.an Development Special Education

Branch Management Analysis

Center, Inc.

- Health - Vocational-Technical

Special Programs Branch - Compensatory Educat ion - Evaluation

School Health Commillee

l'"

--H-aw--ai_i_M_e_d-ic-al_A_s-so-c-ia-ti_o_"_ ~,-------~*~------~ ~ Direct Assist.ance (districts) ~ District SuperintendentS

- Guidance Curriculum Development & Technology

- Hawaii Curriculum Center Office of Personnel Services

- Recruitment & Employment Other SI.ate Agencies Dept. of Health Curriculum Specialists

- Career Management & Principals Dept . of Social Services and Housing

Budget and finance Dept. of Accounting and

General Services Legislative Reference Bureau Legislative Auditors Office

Teachers (Council for Exceptional Children l

Support personnel (Student Council for Exceptional Children)

Development Office of Business Services Office of Research & Planning

- Planning Services - Budget Services - Management Services

2. Provide, as early as possible, for special educational services and programs to help overcome, compensate for or cope with the interference to learning resulting from the handicapping condition.

3. Provide individualized program plans to guide and evaluate individual child progress.

4. a. Provide for maximum interaction of the handicapped student with the general school population, appropriate to the needs of both populations.

b. Provide special_g~rvices to and supplel]'lent / the regular education program for those special - education students who are integrated into general

education. c. Provide consultation services to assist regular

./ education teachers in modifying programs and techniques for handicapped students who remain in general education.

d. Provide means by which a smooth transition of • ,,. students from special to regular education can be

made so that they can meet success in coping with the complexities of regular education.

5. Provide for appropriate career and vocational

8

- Information Systems

preparation education for special education services. 6. Provide for on-going parent participation and involvement with the child's educational program and assist in the provision of parent education and counseling. !· Coo~dinate services ~ith other agencies involved m serv1~es to the handicapped in order to provide alternative and follow-up educational and training programs for those students whose development may be best met by other agency programs.

The details of program delivery options, specifics of particular programs and other important questions have been delineated in the State Plan for Special Education through the assistance of the many individuals and agencies shown in chart 4 . For the handicapped, there is now a guide to establishing "programs that will adequately accommodate those students with special needs."

It is with a profound sense of appreciation for this wide input from many sources that we move ahead in the 70's, to continue to implement and augment the state's commitment to equality of educational opportunity for all children.

![Special Education: Its Ethical Dilemmas, Entitlement ...lawreview.uchicago.edu/sites/lawreview.uchicago... · 2012] Special Education 3 for All Handicapped Children Act 11 (EAHCA),](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5f478fc16bfe2b63df78cb36/special-education-its-ethical-dilemmas-entitlement-2012-special-education.jpg)