A Re-Appraisal of the Fertility Response to the Australian Baby Bonus

-

Upload

sarah-sinclair -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of A Re-Appraisal of the Fertility Response to the Australian Baby Bonus

JEL classifications: J11, J13, J18Correspondence: Sarah Sinclair, School of Econom-

ics, Finance and Marketing, RMIT University, 239Bourke Street, Melbourne, VIC 3001, Australia.

1 It should be noted that the ‘baby bonus’ replacedtwo birth subsidy programs, one which was meanstested and the other which worked through the taxa-tion system. The maternity payment of $842 waslimited to those women on modest incomes, while thematernity allowance, which was characterised by lowutilization rates, functioned as a delayed tax rebateover a five-year period and most benefitted thosewomen on higher incomes in the year prior to mater-nity leave. See Gans and Leigh (2009) for a moredetailed review.

THE ECONOMIC RECORD, VOL. 88, SPECIAL ISSUE, JUNE, 2012, 78–87

Email: [email protected]

A Re-Appraisal of the Fertility Response to theAustralian Baby Bonus

SARAH SINCLAIR, JONATHAN BOYMAL and ASHTON DE SILVA

School of Economics, Finance and Marketing, RMIT University

� 2012 The Economdoi: 10.1111/j.1475

The Australian baby bonus offering parents $3,000 on the birth ofa new child was announced on 11 May 2004. The availability of fiveyears of birth data following the introduction of the baby bonusallows for a more comprehensive analysis of the policy implicationsthan is current in the literature. The focus of this paper is to identifyif there is a positive fertility choice response to the introduction ofthe Australian baby bonus policy and if this response is sustainedover time. To do this, 19 years of birth and macroeconomic data,beginning in 1990, is analysed using an unobservable componentsmodel. The results indicate a significant increase in birth numbersten months following the announcement of the baby bonus, and thisoverall increase was sustained up to the end of the observed period.A cumulative growth in birth numbers which commenced in January2006 slows in 2008 and 2009. It is suggested that the initial increasein births, identified in March 2005, is a direct fertility response tothe introduction of the policy, and that the subsequent change in thegrowth of birth numbers may be the result of a delayed effect work-ing through a number of channels. We estimate that approximately108,000 births are attributable to the baby bonus over the period, atan approximate cost of $43,000 per extra child.

I Introduction and BackgroundDeclining fertility levels are a major concern

for many developed economies as they are asso-ciated with higher dependency ratios (McDonald& Kippen, 2001). Australia is no exception – thefertility rate in 2003, prior to the introduction ofthe baby bonus, was 1.75, which is considerablylower than the estimated replacement level of2.1 children per female.

In response to low fertility levels, the Austra-lian Government announced the introduction of

78

ic Society of Australia-4932.2012.00805.x

the baby bonus in May 2004, a policyspecifically designed to increase fertility levels.1

There have been a number of adjustments to thepolicy since its inception. Initially the federalgovernment pledged each mother a lump sum

2012 A RE-APPRAISAL OF THE AUSTRALIAN BABY BONUS 79

payment of $3000 for each child born after 30June 2004. This amount was subsequentlyincreased in July 2006 and July 2008 to $4000and $5000, respectively.2 There are no studiesto date that have considered whether the babybonus has had a sustained effect on the nationalfertility rate, nor any that have attempted togauge the impact of macroeconomic influenceson the fertility rate in Australia over the sameperiod. By using a structural time series model(Harvey, 1991) we examine the impact of thebaby bonus policy on fertility in Australia untilSeptember 2009. In particular, the number ofbirths per 1000 women of child-bearing age ismodelled with a view to determine whether thebaby bonus has had a temporary or sustainedeffect on fertility levels. Economic determinantsare also controlled for. Thus, this investigationgoes some way to addressing the apparent gapsin the literature.

A temporary fertility effect may take twoforms. First, a short-term policy introductioneffect exists if couples are sufficiently motivatedto have children as a result of the publicity sur-rounding the announcement of the policy. Givensuch an effect, the number of births would tem-porarily increase approximately nine monthsfollowing the announcement before returning totheir long-run path after a short period of time.

The second type of temporary effect is a com-pression effect. This is the case when the timingof births is brought forward as a result of thepolicy. If a compression effect occurs, the fertil-ity rate would temporarily increase and thendecrease relative to the long-run path. However,fertility timing effects are not completely neu-tral with respect to long-term population growthdue to a compressing of the generational cycle.Indeed, Lutz and Skirbekk (2005) advocate theimplementation of policies to affect the timingof births over a woman’s life cycle. The ratio-nale is that the higher fertility rates are in theshort term, the stronger the force of positivemomentum in the longer run.

2 A significant change also occurred on 1 January2009. Specifically, the baby bonus was means testedand payable in 13 equal installments if the total fam-ily income equaled $75,000 or less in the first 6months following the birth of the child. It is difficult,however, to determine what effects this might havehad, given that not enough data following this policychange is available at this point in time.

� 2012 The Economic Society of Australia

A priori, there is no reason to assume that thebaby bonus will have only a temporary effect onfertility, as the initial fertility response may bemaintained, or even magnified, over time.Endogenous social norm effects may act toinfluence the fertility choices of women whowere not initially directly affected by the sub-sidy itself. An individual’s fertility decisionmaking may change not only because of achange in government payments but alsobecause of the behaviour of their peers.

Furthermore, a delayed fertility response mayemerge due to resource constraints and policyinformation lags. Individuals and couples mayalso need to put in place social and medical sup-ports before they have children.3 This may beparticularly relevant for couples engaging inAssisted Reproductive Technology (ART) pro-cedures (i.e. IVF), which have become increas-ingly utilised in recent years.4 Therefore,although decisions to have a child may be madein a timely fashion, the actual fertility responsemay take longer to occur.

Previous studies suggest that a pronatalistpolicy can have a positive effect on fertility,although the cost tends to be high. For example,Gauthier and Hatzius (1997) simultaneouslyconsider cash benefits and maternity leave. Thedependent variable they used is the log of totalfertility using data from 22 industrialised coun-tries from 1970 to 1990.

Their results found the decision to bear achild was affected by ‘its direct cost which islowered by the government subsidy, but not bythe opportunity costs involved in taking time offwork’ (Gauthier & Hatzius, 1997, p. 300). Theyalso found that increasing assistance for the firstchild had a greater effect on fertility than forsubsequent children. The economic control vari-ables they used include unemployment, men’swages, women’s wages, and the change in theunemployment rate. Counter to theoreticalexpectation they found men’s wages positive yet

3 A recent study by the Australian Institute forFamily Studies (Gray et al., 2008) suggests that indi-viduals, on average, want to have more children thanthe replacement fertility level of 2.1, however due tofinancial constraints, as well as work-related issuesand partnership issues, have no plans to do so.

4 Increasing from 6792 live births in 2004 to10,633 live births in 2008; Table 35, p. 43, ART inAustralia and New Zealand 2008, AIHW, AssistedReproduction Technology Series Number 14.

7

80 ECONOMIC RECORD JUNE

insignificant and women’s wages negative andonly significant at the 10 per cent level. Thechange in the unemployment rate was found tobe highly significant. In addition, differenceswere noted between subgroups – no evidencewas found that cash benefits affect fertility inthe Anglo Saxon countries; however, benefitshad a large and consistent effect in the Scandi-navian countries, with continental and south-ern Europe in between (Gauthier & Hatzius,1997).

A policy implemented in the province ofQuebec that paid families up to $8000 for hav-ing a child5 provides a natural experiment infertility choice and as such has stimulated someinteresting studies. Milligan (2005) found evi-dence that the policy achieved its goal ofincreased fertility and attributed 93,000 births tothe policy over the 10-year period. In addition,Milligan (2005) also found that higher incomewas associated with a larger fertility effect forcash payments.6

Preceding Milligan (2005), Duclos et al.(2001) used a difference in difference estimatorto identify the impact of the Quebec baby bonusscheme. They found that generous family bene-fits do have an effect on fertility rates, in partic-ular providing strong incentive to give birth to athird child in Quebec.

The Australian baby bonus scheme has alsoreceived significant research attention since itsinception in 2004. Much of the economic analysison the Australian baby bonus has been focused ondistortionary birth timing effects, fertility inten-tions, or state specific impacts. For example,Gans and Leigh (2009) have analysed the short-term birth timing effects of the introduction ofthe policy. They used daily birth numbers from1975 to 2004, focusing on the days immediatelypreceding and following July 1 of each year.Using standard regression techniques they con-clude that up to 1000 births (primarily discretion-ary caesareans) may have been delayed as a resultof the introduction of the baby bonus. Based onsimilar analysis of the 2006 baby bonus increase,they conclude approximately 600 births weredelayed in this instance (Gans & Leigh, 2007).

5 The Allowance for Newborn Children gave apayment of $500 for a first child and up to $8,000 fora third.

6 This is consistent with experience of the babybonus in Western Australia (see Langridge et al.,2012, discussed below).

Drago et al. (2010) make use of HILDA7

household panel data to assess if the baby bonusincreased fertility intentions and thereby births,and if the effects were temporary or sustained.They investigate whether the effects were con-centrated among particular income groups andthose women who already had children. Asimultaneous equations approach was used, withfertility intentions treated as endogenous in amodel predicting births, thus testing the effectof the baby bonus on fertility intentions. Theiranalysis included variables that capture theopportunity cost of birth such as labour forcestatus, education and income. They found thatfertility intentions rose after the announcementof the baby bonus, and the birth rate was esti-mated to have risen modestly as a result.

Lain et al. (2009) use a Poisson regressionanalysis of New South Wales (NSW) birth num-bers and Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)Population estimates to assess the effect of thebaby bonus on birth rates. They analyse thechange in the birth rates in 2005 and 2006 rela-tive to the trend before the introduction of thebonus and find that birth rates increased, espe-cially among women having their second or sub-sequent child.

A further study by Lain et al. (2010) hasevaluated the impact of the baby bonus on NSWhealth services and they estimate an additional11,283 births per year in NSW due to the babybonus, at a cost to the health care system of anadditional $60 million in 2008.8 An analysis ofthe policy impact in Western Australia was con-ducted by Langridge et al. (2012), and usingsimilar statistical techniques to Lain et al.(2010) found a positive increase in fertility, par-ticularly in women residing in higher socioeco-nomic areas.

II Theoretical BackgroundMuch of the economic theory of fertility

within the rational choice framework originatesfrom the works of Becker (1960) andLeibenstein (1957). It is assumed that fertility is

Refer to Wooden and Watson (2007) for adetailed description of the Household, Income andLabour dynamics in Australia Survey (HILDA).

8 Negative binomial regression was used on datafrom 1998 to 2004 to generate a predicted number ofbirths in 2008. The predicted number was then com-pared with observed numbers to identify a deviationfrom the pre-baby bonus trend.

� 2012 The Economic Society of Australia

2012 A RE-APPRAISAL OF THE AUSTRALIAN BABY BONUS 81

a conscious decision and the essence of themodel is that families balance the benefit againstcost of an additional child, given that childrenare assumed to be a normal good.9 Therefore,fertility behaviour can be analysed within achoice theoretic framework wherein family size(given preferences) is the result of variations inincome and the ‘costs’ inclusive of the opportu-nity cost of children (Hotz & Miller, 1993).

The ‘cost’ variable incorporates the theory ofthe allocation of time, the concepts of householdproduction theory and human capital investmenttheory. Given that the rearing of children is con-sidered time intensive relative to other house-hold production, the cost of child bearing (andrearing) is in the most part a function of themother’s time. The interaction of these variablesis complex in the context of fertility choice, forexample rising female labour participation rates,less gender specialisation, and higher humancapital investment and wages for women repre-sents rising family incomes yet a higher oppor-tunity cost to childbearing. Therefore therelative strength of the income and substitutioneffects is of significance when assessing theinfluence of changing family policy on fertility.Ultimately a universal subsidy to lower the costor ‘price’ of children would be expected toincrease the demand for children and this wouldbe reflected in higher birth numbers.

Recent developments in the family economicsliterature have also highlighted the role of thesocial climate and social interactions on fertilitychoice. The rational choice model of fertilityhas been extended to include social interaction,on the basis that individuals use the situationalinformation available to them. Becker andMurphy (2003), suggest that ‘the number andeducation of children are affected by the behav-iour of friends, peers and neighbours … birthswithin a group could respond sharply to smallchanges in explanatory variables because thesocial multiplier magnifies the responses of themembers of the same social group’ (Becker &Murphy, 2003, p. 21). Economic models havebeen developed for the study of ‘socially

9 After a peak in Australian fertility in 1961, majorsocial changes such as increased access to oral contra-ceptives in the 1960s and increased female labourforce participation in the 1970s resulted in markeddeclines in Australian fertility. Since 1976 the Austra-lian Total Fertility rate has since remained below thereplacement rate of 2.1 (ABS, 2010b, p. 204).

� 2012 The Economic Society of Australia

embedded’ fertility behaviour such as that ofKohler (1997). Durlauf and Walker (1999) sug-gest that endogenous social effects generatesocial multipliers which exist when the totaleffect of an individual’s decision on the overallpopulation behaviour is larger than the initialdirect effect of her choice. For example, a cou-ple may respond directly to the financial incen-tive of the policy, yet may communicatepositive experiences of child-bearing to friends,colleagues etc. and through social learninginduce other couples to consider child bearing.Kuziemko (2006) explores one aspect of socialinteraction by using micro level data to test iffertility peer effects exist. It was found that theprobability of having a child rises by 15 percent in the two years following the birth of aniece or nephew. The effect is strongest when itis a sister that has a child and when cost savingfrom co-ordination is most likely.10

Discussion of the impact of social interactionson fertility extends the notion that initial positivechanges in fertility can have longer-term impactson population growth. However, the purpose ofthis paper is to quantify the effectiveness of thepolicy in changing fertility rates, and while thesebehavioural models provide a useful insight as towhy policy might be effective, incorporatingbehavioural aspects is beyond the scope of thispaper.

III MethodologyIn this section, we outline the structural time

series model used to quantify the effect of thebaby bonus. We apply this model to three differ-ent birth measures: monthly birth numbers,monthly fertility rates and quarterly fertilityrates, thus enabling key economic variables tobe taken into account.

The birth and population data spans January1990 to October 2009 and is sourced from theABS. The fertility rate is defined as the number ofbabies born per 1000 women of child-bearing agewhere child-bearing age is defined as femalesaged between 15 and 49.11 The fertility rate iscalculated on the basis of annual estimated resi-dential population of females aged 15–49.

10 Refer to Durlauf and Walker (1999) for a surveyof empirical evidence on fertility transitions relevantto the social interactions model.

11 Estimated annual residential population offemales aged 15–49 is sourced from ABS catalogue3101, Table 9 series id – A2159036V – A2159070T.

82 ECONOMIC RECORD JUNE

From July 2007 it was a requirement to for-mally register the birth of a child to be eligiblefor receipt of the baby bonus. It should be notedthat late registrations of births are recorded inthe registration year as opposed to the birthyear and therefore the ABS data series maydeviate from actual hospital records in the yearsprior to obligatory registration (McDonald,2005).

The structural time series model is fitted tothe data using STAMP (Koopman et al., 2006).Specifically, the model we fit (assuming yt

denotes the fertility rate at time t) has the fol-lowing general form:

yt ¼ lt þ ct þHXt þUZt þ et; et�NIDð0;r2e Þ; ð1Þ

lt ¼ lt�1 þ bt�1 þ gt; gt� NIDð0;r2gÞ; ð2aÞ

bt ¼ bt�1 þ 1t; 1t� NIDð0;r21Þ; ð2bÞ

ct ¼Xs=2

j¼1

cj;t;cj;t

c�j;t

" #

¼cos kj sin kj

� sin kj cos kj

� �cj;t�1

c�j;t�1

" #

þ-j;t

-�j;t

" #; -t � NIDð0;r2

-Þ:

where lt, ct, Xt and Zt denote the trend, sea-sonal, explanatory and policy intervention vari-ables at time t. Equation (1) is often referred toas the observation equation, whereas Equations(2a)–(2c) are a set of measurement or stateequations. The trend (Eqns 2a and 2b) is madeup of two components, lt–1 and bt–1, where bt

captures the growth rate in the series and lt–1

the level.The coefficients Q and F measure the direc-

tion and size of the explanatory and policyintervention variables respectively. Importantly,by including a set of policy intervention vari-ables we are able to measure the departure fromunderlying trend12 in fertility rates coincidingwith the introduction and subsequent modifica-tions in the baby bonus policy.

12 Note the underlying trend is a general term refer-ring to the whole data generating process as depictedby all equations of the structural time series modelexcluding the term FZt.

Three types of policy intervention variablesare considered in the subsequent section. Thefirst corresponding to that presented in Equa-tion (1), which represents a positive or nega-tive spike (impulse) in the data. This type ofintervention corresponds to the Gans andLeigh (GL) birth timing effect (Gans & Leigh,2009).

That is by specifying impulse dummies in themeasurement equation of the form:

yt ¼ lt þ ct þ /1d2004;6 þ /2d2004;7 þ et; ð3Þ

the GL effect can be measured. Specifically ifthe baby bonus had a significant birth timingeffect, then the coefficient /1 should be nega-tive and significantly different from zero and /2

should be positive and significantly differentfrom zero (assuming the variable was behavingconsistently with its historical time path).

The second and third types correspond toEquations (2a) and (2b), representing a changein the underlying level (mean) and slope(growth rate) in the data. These changes arecharacteristically different from the GL timingeffect, indicating structural changes in the fertil-ity behaviour exhibited by the population as awhole has occurred.

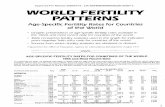

IV ResultsBefore presenting and interpreting our

results we briefly discuss the fertility ratesover the last two decades. Figure 1 presentsthe fertility rate beginning in January 1990 upuntil October 2009. Two distinguishing fea-tures are evident, one, the decline in the gen-eral rate for first 15 years and two, thenoticeable increase following the introductionof the baby bonus.

The shaded area in Figure 1 corresponds toMarch 2005 to October 2009, identifying theperiod in which the policy could have had aneffect given the nature of the reproductivecycle. The date at which the policy was intro-duced is also identified.

Importantly, the pronounced change in March2005, approximately 10 months following theannouncement of the baby bonus, suggests thatthe policy has had an impact on fertility rates.By using the structural model outlined in theprevious section we are able to quantify thisstructural change and hence the change in theunderlying fertility behaviour of the populationas a whole.

� 2012 The Economic Society of Australia

3.5

3.7

3.9

4.1

4.3

4.5

4.7

4.9

5.1

5.3

5.5

Fertility rate

Date

Australian fertility rate

Policyintroduction

July 2004

1990

-1

1990

-9

1991

-5

1992

-1

1992

-9

1993

-5

1994

-1

1994

-9

1995

-5

1996

-1

1996

-9

1997

-5

1998

-1

1998

-9

1999

-5

2000

-1

2000

-9

2001

-5

2002

-1

2002

-9

2003

-5

2004

-1

2004

-9

2005

-5

2006

-1

2006

-9

2007

-5

2008

-1

2008

-9

2009

-5

FIGURE 1Australian Monthly Fertility Rates Calculated Using Data From the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS,

2011a): Data Catalogue Nos 3301 and 3201.0

Note: The fertility rate is defined as the number of births divided by the annual estimated resident population of females aged15–49.

2012 A RE-APPRAISAL OF THE AUSTRALIAN BABY BONUS 83

We begin by considering two modes13 of thedependent variables; birth numbers and fertilityrate. Our first model considers whether shortterm birth timing effects of the type identifiedby Gans and Leigh (2009) are evident on theintroduction of the policy in July 2004 and forsubsequent changes in magnitude and structureof the policy.

The results in Table 1 concur with the Gansand Leigh (2009) finding. However, they do notsupport their subsequent findings regarding abirth timing effect in 2006 as the result of theincreased value of the baby bonus (Gans &Leigh, 2007). Similarly, the results do not sug-gest a birth timing effect corresponding to the2008 increase (assuming a = 0.05). However,they do indicate that in December 2008 anabnormally high number of babies were born,suggesting the decision to means test the babybonus from 1 January 2009, had a significantimpact on the timing of births.

13 Full reports of the model fit are available uponrequest from the authors.

� 2012 The Economic Society of Australia

The results in Table 1, however, simply iden-tify if there was a birth timing effect in responseto the policy introduction and shed little lighton whether there has been a fertility response.To test this, births per 1000 women of child-bearing age are modelled.

In terms of the fertility effect, a change in thepattern of the data is tested corresponding to thedate March 2005, 10 months following theannouncement of the introduction of the babybonus. In particular a change in the mean istested. Model 2 is further refined by eliminationof insignificant variables in the model and theinclusion of the slope break intervention whichrelates to a delayed reaction to the policy intro-duction. While delayed birth registration mayimpact the estimated timing of the delayed reac-tion, it does not alter the existence of such adelay.

Table 2 presents the results of this secondmodel. The results suggest that the fertilityrate changed significantly approximately ninemonths after the introduction of the baby bonus.

Specifically, the results in Table 2 support theobservations made in relation to Figure 2, and

TABLE 2Coefficient Estimates and Selected Diagnostics:

Model 2

Break-type Date Coefficient P-value

Levelbreak

March 2005 0.221 <0.001

Slopebreak

January 2006 0.015 <0.001

Slopebreak

January 2008 )0.019 <0.001

Impulse June 2004 )0.265 <0.001Impulse December 2008 0.346 <0.001Impulse November 1990 0.407 <0.001

r2 = 0.56 Normality= 0.26*

DW = 1.85*

Notes: *The critical value for the Normality test (where nullcorresponds to normality) is 5.99 (v2

2; Koopman et al.,2006, p. 201) thus indicating the residuals are normallydistributed. The P-value for Durbin Watson is 0.41 whichindicates autocorrelation is not present (Harvey, 1990). Thedependent variable relating to the estimates provided is thenumber of babies born per 1000 women of child-bearing age.The frequency of the data is monthly. Each coefficientrepresents a deviation from the underlying trend. Threeforms of deviation are determined, a shift in the mean (levelbreak), a change in the growth rate (slope break) and a seriesof one-off spikes (impulse). The estimates presented are thestatistically significant deviations corresponding to theintroduction and subsequent policy changes in the babybonus scheme. The November 1990 coefficient is the onlyexception corresponding (as before) to a data irregularitydetected when fitting the model.

TABLE 1Coefficient Estimates and Selected Diagnostics:

Model 1

Date Coefficient P-value

June 2004 )1248 0.001July 2004 783 0.040June 2006 )333 0.380July 2006 258 0.496June 2008 )497 0.496July 2008 795 0.037December 2008 1634 <0.001January 2009 )277 0.400November 1990 1733 <0.001December 1990 )716 0.060r2 = 0.54 Normality = 0.75* DW = 2.07*

Notes: *The critical value for the Normality test (where nullcorresponds to normality) is 5.99 (v2

2; Koopman et al.,2006; p. 201) thus indicating the residuals are normallydistributed. The P-value for Durbin Watson is 0.70, whichindicates autocorrelation is not present (Harvey, 1990). Thedependent variable relating to the estimates provided is thenumber of babies born. The frequency of the data is monthly.Each coefficient represents a deviation from the underlyingtrend in the form of an impulse. The dates chosen reflect theintroduction and subsequent policy changes in the babybonus scheme. The coefficients relating to the year 1990 arethe only exceptions corresponding to data irregularitiesdetected when fitting the model.

84 ECONOMIC RECORD JUNE

therefore concur with the delay hypothesis.They indicate that at least 0.221 additionalbabies have been born per 1000 women ofchild-bearing age, per month, since March 2005,(approximately 1100 babies using annual popu-lation estimates) and that this was reinforced bya delayed fertility effect with a cumulativeincrease of 0.015 babies per 1000 women permonth (approximately 70 babies) every monthbetween January 2006 and December 2007.

Interestingly, the coefficient estimates of theslope break approximately add to zero, suggest-ing that the cumulative delayed increases havebeen maintained, that is an approximate addi-tional 1700 babies have been born each monthsince January 2008.14 Further, these results sug-

14 Calculated as 0.221 + 0.36 babies per 1000women of childbearing age per month. The value 0.36is calculated by assuming that the second slopechange perfectly offsets the first, given the standarderrors for the January 2006 and January 2008 coeffi-cients are 0.003 and 0.005, respectively, this is a validassumption. The 0.36 is therefore the cumulativedeparture from the underlying historical fertility ratefor the month of December 2007, specifically0.015 · 24.

gest that up to June 2009 approximately 108,000births can be attributed to the baby bonus policyincentives. The calculated direct cost of eachadditional birth is in the region of $43,000.15

In Figure 2, the trend estimate for the periodJanuary 2003 to October 2009 is presented. Anincrease in the trend in January 2006 is consis-tent with a delayed fertility response to theintroduction of the policy. It should be notedthat this increase in the trend takes place beforethe July 2006 increase in the baby bonus, andtherefore potentially reflects a delayed responseto the initial introduction of the baby bonus,rather than the impact of additional financialincentives. While subsequent growth in birthnumbers appears to have peaked by January2008, the true magnitude of this delayed effectwill become clearer over time as more databecomes available.

15 Refer to Table 9.22 in ABS (2010a) for a totalestimated cost of the baby bonus 2004–2009.

� 2012 The Economic Society of Australia

TABLE 3Model Output Economic Effect

Type Date Coefficient P-value

Level break 2005 Q1 0.592 <0.001Slope break 2006 Q1 0.133 <0.001Slope break 2008 Q1 )0.108 0.042Impulse 2004 Q2 )0.333 0.048Impulse 2008 Q4 0.168 0.312AWEt–4 )0.001 0.760RGDPpct–4 )0.0003 0.149

r2 = 0.50 Normality= 0.68*

DW = 2.11*

Notes: *The critical value for the Normality test (where nullcorresponds to normality) is 5.99 (v2

2; Koopmans, 2006,p. 201) thus indicating the residuals are normally distributed.The P-value for Durbin Watson is 0.70 which indicatesautocorrelation is not present (Harvey, 1990). The dependentvariable relating to the estimates provided is the number ofbabies born per 1000 women of child bearing age. Thefrequency of the data is quarterly. Each break coefficient

3.75

4

4.25

4.5

4.75

2003

-1

2003

-4

2003

-7

2003

-10

2004

-1

2004

-4

2004

-7

2004

-10

2005

-1

2005

-4

2005

-7

2005

-10

2006

-1

2006

-4

2006

-7

2006

-10

2007

-1

2007

-4

2007

-7

2007

-10

2008

-1

2008

-4

2008

-7

2008

-10

2009

-1

2009

-4

2009

-7

2009

-10

Fertility rate

Date

Fertility trend estimate: model 1

FIGURE 2Fertility Rates and Estimated Trend Including Intervention Estimates from January 2003 to September 2009

Note: The fertility rate is defined as the number of births divided by the number of women of child-bearing age (15–49).

2012 A RE-APPRAISAL OF THE AUSTRALIAN BABY BONUS 85

(i) Controlling for Economic InfluenceIn this section intervention effects are re-esti-

mated while controlling for economic factorsthat could plausibly be associated with changesin fertility. Changes in women’s wages, forexample, may influence the opportunity cost ofbearing and rearing children, while higher levelsof household income may reduce financial con-straints and therefore increase the demand forchildren. Average weekly earnings for females(AWE) and real GDP per capita (RGDPpc)lagged four quarters are therefore used in thissection as controls to test for the effect of thebaby bonus on birth rates. As the relevant eco-nomic data is recorded quarterly the monthlyrates used previously must be converted intoquarterly rates (ABS, 2010).

The quarterly conversion undertaken involvestwo steps. The first step is to aggregate thenumber of births over the relevant threemonths for each quarter. This figure is thendivided by the estimated number of women ofchild-bearing age as at the end of the quar-ter.16 Effectively, this calculation results in atrebling of the average monthly rate for eachquarter.

16 Estimated population by age is only availableannually.

� 2012 The Economic Society of Australia

Table 3 presents the coefficient estimates ofthe intervention and economic variables. For theperiod from January 1990 to October 2009, noneof the economic determinants of fertility testedare statistically significant. This may be a

represents a deviation from the underlying trend. Threeforms of deviation are determined, a shift in the mean (levelbreak), a change in the growth rate (slope break) and a seriesof one-off spikes (impulses). The estimates presentedcorrespond to the introduction and some subsequent policychanges in the baby bonus scheme.

86 ECONOMIC RECORD JUNE

reflection of the relatively stable growth experi-enced over the observed period.

Importantly, although quarterly rather thanmonthly data was utilised, the interventioneffects remain consistent with the findings ofthe previous section, with the exception of theDecember 2008 outlier. Notably, the level breakis approximately three times larger in Table 3than it is in Table 2. Further, we also note thatthe slope coefficients are statistically insignifi-cant from six17 times the coefficient estimates inTable 2.

V ConclusionThis paper analyses the impact of the Austra-

lia baby bonus on Australian births betweenMarch 2005 and September 2009 using an un-observable components model. The results indi-cate a significant increase in birth numbers tenmonths following the announcement of the babybonus, and that this initial policy introductioneffect was maintained, as were the cumulativedelayed increases in births. The results are con-sistent with the discretionary birth timing effectidentified by Gans and Leigh (2009) as a resultof the introduction of the baby bonus in July2004. However, the results do not support theexistence of such an effect following the 2006increase in the value of the baby bonus (Gans &Leigh, 2009). It may be that the increment inthe bonus was not deemed sufficient to motivatea delay in discretionary timing of births. Theanalysis did not find any significant impact ofreal gross domestic product per capita and aver-age weekly female earnings on fertility. Thismay be due to the relatively stable growthachieved in Australia over this period, or thecomplex interaction of income and substitutioneffects on fertility choice.

The existence of a purely temporary fertilityeffect and a compression effect are not sup-ported by the data, given the sustained increase

17 Note for month one, two and three, the deviationcumulates resulting in estimated deviations of 0.015[1 · 0.015], 0.038 [2 · 0.015] and 0.052 [3 · 0.015],respectively. Therefore, for any given quarter theapproximate slope deviation using monthly data isestimated to be 0.09 = [6 · 0.015], which is statisti-cally indifferent from 0.133 given the standard erroris estimated to be 0.037. Similarly, the 95% confi-dence interval for the January 2008 slope interventionis ()0.006, )0.200), which contains the estimatedmonthly quarterly estimate of )0.108 [6· = 0.018].

in birth rates over a four-year period, although alonger time frame may be needed to exclude thepossibility of a recuperation effect whereinhigher fertility rates at these significant dateswere driven by women who were having chil-dren previously delayed, thus having no netpositive effect on their completed fertility.

While this paper has focused on the quantityimplications of the baby bonus, both the changein births following the means testing of thepayment support and research such as that ofLain et al. (2009) and Langridge et al. (2012)suggest that there may be a heterogeneousresponse to the policy across the population.Lain et al. (2009) found that the greatestincrease in the NSW birth rate relative to thetrend was observed in teenagers, whileLangridge et al. (2012) found that in WesternAustralia the greatest increase in births wasamong those women living in high socio-economic areas. Given the delayed effects iden-tified in this paper, it may take time for the‘quality’ implications of the baby bonus (i.e. thewellbeing of the child and utility of the parents)to emerge. Finally, the aggregation of both birthdata and population means that subtleties infamily decision making cannot be modelled.18

A key future research focus then, is to assessthe variability in the response, and delay inresponse, to the baby bonus across age, culturalbackground, socio-economic status and educa-tion. It is concluded that the baby bonus has hada significant and positive effect on fertilityrates; however, this effect has not been largeenough to increase the fertility rate to thereplacement level. Further, the recent change ofmean testing the baby bonus may reduce theoverall influence. This suggests that more needsto be done to increase the fertility rate in theinterest of future long term economic prosperity.

REFERENCES

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2010a),2009 ⁄ 10 Year Book Australia, Catalogue Number1301.0. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra,Australia. [Cited 20 June 2010.] Available from:http://www.abs.gov.au.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2010b), Births,Australia. ABS cat. no. 3301.0. Australian Bureau

18 The ABS (2011b) data does not distinguishbetween planned and unplanned pregnancies or traceabortions and births in relation to unplanned pregnancies.

� 2012 The Economic Society of Australia

2012 A RE-APPRAISAL OF THE AUSTRALIAN BABY BONUS 87

of Statistics, Canberra, Australia. [Cited 25 June2010.] Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2011a), Aus-tralian Demographic Statistics. ABS cat. no.3101.0 Table 4. Australian Bureau of Statistics,Canberra, Australia. [Cited 20 January 2011.]Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2011b),Australian National Accounts. ABS cat. 5206, cat1345. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra,Australia. [Cited 15 January 2011.] Available from:http://www.abs.gov.au.

Becker, G.S. (1960), An Economic Analysis of Fertility.Demographic and Economic Change in DevelopedCountries. Princeton University Press for the NationalBureau of Economic Research, Princeton, NJ.

Becker, G.S. and Murphy, K.M. (2003), Social Eco-nomics: Market Behavior in a Social Environment.Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cam-bridge, MA.

Drago, R., Sawyer, K., Sheffler, K., Warren, D. andWooden, M. (2010), ‘Did Australia’s Baby BonusIncrease Fertility Intentions and Births?, PopulationResearch and Policy Review, 30, 381–97.

Duclos, E., Lefebvre, P. and Merrigan, P. (2001), ‘ANatural Experiment on the Economics of Storks:Evidence on the Impact of Differential Family Pol-icy on Fertility Rates in Canada’, Working PaperNo. 136, Center for Research on Economic Fluctua-tions and Employment (CREFE), University ofQuebec, Montreal.

Durlauf, S. and Walker, J. (1999), ‘Social Interactionand Fertility Transitions’, Working Papers 28, Wis-consin Madison – Social Systems.

Gans, J.S. and Leigh, A. (2007), ‘Born (Again) on theFirst of July: Another Experiment in Birth Timing’,The Selected Works of Joshua S Gans. [Cited20 March 2012.] Available from: http://works.bepress.com/joshuagans/15.

Gans, J.S. and Leigh, A. (2009), ‘Born on the First ofJuly: An (Un)Natural Experiment in Birth Timing’,Journal of Public Economics, 2009, 93, 246–63.

Gauthier, A. and Hatzius, J. (1997), ‘Family Benefitsand Fertility: An Econometric Analysis’, PopulationStudies, 51, 295–306.

Gray, M., Qu, L. and Weston, R. (2008), Fertility andFamily Policy in Australia. Australian Institute ofFamily Studies, Melbourne.

Harvey, A.C. (1990), The Econometric Analysis ofTime Series, 2nd edn. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Harvey, A.C. (1991), Forecasting, Structural TimeSeries Models and the Kalman Filter CambridgeUniversity Press, Cambridge, UK.

� 2012 The Economic Society of Australia

Hotz, V.J. and Miller, R.A. (1993), ‘ConditionalChoice Probabilities and the Estimation of DynamicModels’, The Review of Economic Studies, 60, 497–529.

Kohler, H.-P. (1997), ‘Fertility and Social Interaction:An Economic Approach (Dissertation)’, Departmentof Economics, University of California, Berkeley,CA.

Koopman, S.J., Harvey, A.C., Doornik, J.A. and Shep-hard, N. (2006), Structural Time Series Analysis,Modelling, and Prediction Using STAMP. 7. Tim-berlake Consultants Press, London.

Kuziemko, I. (2006), ‘Is Having Babies Contagious?Estimating Fertility Peer Effects Between Siblings’,Harvard University Working Paper. [Cited 24 March2012.] Available from: http://www.princeton.edu/~kuziemko/fertility_11_29_06.pdf.

Lain, S.J., Ford, J.B., Raynes-Greenow, C.H.,Hadfield, R.M., Simpson, J.M., Morris, J.M. andRobert, C.L. (2009), ‘The Impact of the BabyBonus Payment in New South Wales: Who is Hav-ing ‘‘One For The Country’’?’, The Medical Journalof Australia, 190, 238–41.

Lain, S.J., Roberts, C.L., Raynes-Greenow, C.H. andMorris, J. (2010), ‘The Impact of the Baby Bonuson Maternity Services in New South Wales’, TheAustralian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics &Gynaecology, 50, 25–9.

Langridge, A.T., Nassar, N., Li, J., Jacoby, P. andStanley, F.J. (2012), ‘The Impact of MonetaryIncentives on General Fertility Rates in WesternAustralia’, Journal of Epidemiology and CommunityHealth, 66, 296–301.

Leibenstein, H. (1957), Economic Backwardness andEconomic Growth. John Wiley and Sons, NewYork, NY.

Lutz, W. and Skirbekk, V. (2005), ‘Policies Affectingthe Tempo Effect in Low Fertility Countries’, Popu-lation and Development Review, 31, 703–23.

McDonald, P. (2005), ‘Has the Australian FertilityRate Stopped Falling?’, People and Place, 13,1–5.

McDonald, P. and Kippen, R. (2001), ‘LaborSupply Prospects in 16 Developed Countries,2000–2050’, Population and Development Review,27, 1–32.

Milligan, K. (2005), ‘Subsidizing the Stork: New Evi-dence on Tax Incentives and Fertility’, Review ofEconomics and Statistics, 87, 539–55.

Wooden, M. and Watson, N. (2007), ‘The HILDASurvey and its Contribution to Economic andSocial Research (So Far)’, Economic Record,83 (261), 208–31.