A PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL WOLF CENTER SPRING … · 2 Letters to the Editor 3 From the...

Transcript of A PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL WOLF CENTER SPRING … · 2 Letters to the Editor 3 From the...

A PUBL ICAT ION OF THE INTERNATIONAL WOLF CENTERSPR ING 2002

Largest Pack Ever Recorded? page 4

With Friends Like These . . . page 8

A PUBL ICAT ION OF THE INTERNATIONAL WOLF CENTERSPR ING 2002

Cover.spring 02 1/24/02 11:57 AM Page 1

Donated collection now available to the public.

Extra savings, low prices!

Limited edition prints by celebrated artists.

Proceeds directly benefit theInternational Wolf Center mission.

Save money on collectible wildlife art and support the survival of wolves worldwide!

The International Wolf Center is a non-profitorganization dedicated to supporting the

survival of wolves worldwide through education.

View our online gallery byvisiting www.wolf.org For private inquiries,please call 763-560-7374Any donation above the already low asking price is tax deductible to the full extent of the law.

Carl Brenders, One-to-OneRobert Bateman, Hoary Marmot

B e v D o o l i t t l e R o b e r t Tr a v e r s L e e K r o m s c h r o e d e r J a m e s M e g e r B r u c e M i l l e r ( a n d m a n y o t h e r s ! )

C a r l B r e n d e r s R o b e r t B a t e m a n R . S . Pa r k e r A l A g n e w D o n G o t t J o r g e M a y o l F r a n k M i l l e r

Check out www.wolf.org for special gifts for your special family and friends. Your purchase provides public education about wolves!

Anniversaries?Anniversaries?

Valentine’s Day?Valentine’s Day?

Birthdays?Birthdays?

Cover.spring 02 1/22/02 8:26 AM Page 2

2 Letters to the Editor

3 From the Executive Director

12 International Wolf CenterNotes From Home

15 Tracking the Pack

16 Wolves of the World

21 As a Matter of Fact

22 Personal Encounter

25 News and Notes

26 Wild Kids

28 A Look Beyond

4How Did the Druid Peak Pack Get to Be So Big?Yellowstone’s Druid Peak pack has grownto 37 wolves. Can this uncommonly large pack maintain its size?

D o u g l a s S m i t h a n d R i c k M c I n t y r e

Features

THE QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL WOLF CENTER VOLUME 12, NO. 1 SPRING 2002

On The CoverPhoto by Lynn and Donna Rogers

8With Friends Like These . . .Wolf restoration used to be a matter of protecting wolvesfrom their enemies. Now managers must protect wolvesfrom their friends as well. Two articles discuss how posi-tive attitudes toward wolves can create new problems. I n t r o d u c t i o n b y S t e v e G r o o m s

Don’t Feed Wolves, Say Experts K e v i n S t r a u s s

Releases of Tame Wolves and Hybrids Give Wild Wolves a Black Eye B i l l P a u l

DepartmentsLy

nn a

nd D

onna

Rog

ers

Dou

glas

Sm

ith/N

PS

Dou

glas

Sm

ith/N

PS

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:42 AM Page 1

Publications DirectorMary OrtizMagazine CoordinatorCarissa LW KnaackConsulting EditorMary KeirsteadTechnical Editor L. David MechGraphic DesignerTricia Hull

International Wolf (1089-683X) ispublished quarterly and copyrighted,2001, by the International Wolf Center,3300 Bass Lake Rd, Minneapolis, MN55429, USA. e-mail: [email protected] rights reserved.

Publications agreement no. 1536338

Membership in the International WolfCenter includes a subscription toInternational Wolf magazine, free admissionto the Center, and discounts on programsand merchandise. • Lone Wolf member-ships are U.S. $30 • Wolf Pack $50 • Wolf Associate $100 • Wolf Sponsor $500 • Alpha Wolf $1000. Canada and othercountries, add U.S. $15 per year for airmail postage, $7 for surface postage.Contact the International Wolf Center,1396 Highway 169, Ely, MN 55731-8129,USA; e-mail: [email protected]; phone: 1-800-ELY-WOLF

International Wolf is a forum for airingfacts, ideas and attitudes about wolf-related issues. Articles and materialsprinted in International Wolf do not necessarily reflect the viewpoint of theInternational Wolf Center or its board of directors.

International Wolf welcomes submissionsof personal adventures with wolves andwolf photographs (especially black andwhite). Prior to submission of other types of manuscripts, address queries to Mary Ortiz, publications director.

International Wolf is printed entirely with soy ink on recycled and recyclablepaper (text pages contain 20% post-consumer waste, cover paper contains 10% post-consumer waste). We encourageyou to recycle this magazine.

PHOTOS: Unless otherwise noted, orobvious from the caption or article text,photos are of captive wolves.

2 S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 w w w . w o l f . o r g

Words Matter

In a recent specia l i ssue ofInternational Wolf on the “Global

Challenge of Living with Wolves,”there are a host of articles about live-stock conflicts with wolves fromaround the world. A common themein many of the articles is that wolvescreate negative impacts on livestockaround the world. I would havestated it the other way around: live-stock create negative impacts onwolves around the world. How wedescribe the issue and the words weuse to describe it have a lot to do withhow we respond.

That’s why I believe it’s importantfor wolf supporters to clearly articulatethat it is the livestock operations thathave been imposed on wolves.Legitimizing the livestock industry’smessage by using their language and their perception of the “problem”to describe wolf recovery issues ultimately harms wolf restoration.

Most of the problems from preda-tors reported by livestock producers

are created by their own animalhusbandry customs. But we seldomhold the producers accountable. Yet when a sloppy camper leaves outfood unattended in a campgroundand is subsequently attacked by abear, we usually hold the camperresponsible for the situation thatcreated the conflict, not the bear. Thereare no “problem” wolves or bears, onlyproblem people. If anyone shouldmodify or change their behavior, itshould be humans. We are alwaystelling ourselves that we’re the mostintelligent animals—maybe it’s timewe started acting like it.

Advocating things like “trainingwolves” with shock collars to avoidlivestock, using collars with sedativesto stop wolves from wandering from predetermined “safe” areas, andso forth poses serious philosophicalquestions about just what kind ofwolves we want. Some are even advocating sterilization of wolves andcoyotes to reduce predation problemsthrough population control, with noattempt to understand how this mayaffect many other things, like thecontrol of smaller rodents andmetapredators by the presence ofthese larger predators.

Such a Brave New World ofwildlife behavior modification repre-sents a fundamentally flawed view ofwildlife. It seeks to take the wild outof wildlife. It creates the illusion ofwildness, all the while maintaining a tight grip on control.

George Wuerthner Box 3156 Eugene, OR 97403

Inte

rnat

iona

l Wol

f Cen

ter

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:42 AM Page 2

Evolution: The Triumph of an Idea is the title of a remarkable new book, by

Carl Zimmer. The book traces, in part, Charles Darwin’s progression of field

experiences and the refinement of his ideas to the creation of the bold

scientific conclusions that defined the principle unifying all life forms. As I read the

book, I found parallels in the unfolding of the concept of evolution with the ever

developing saga of wolf restoration. Despite enormous pressures and against significant

odds, the power of these two brilliant ideas has prevailed—notwithstanding ongoing

controversies and often immense challenges.

Perhaps the 150 years of controversy surrounding Darwin’s ideas should

suggest to us that while we have made progress in building support for the

concept of wolf restoration philosophically and on the ground, we have

just begun to experience the challenges this bold idea will face far into the

future. And just as more pieces of the evolution jigsaw puzzle have been

found over the past decades to reinforce the theory, examples of wolves

and humans successfully coexisting—as in Minnesota, Michigan and

Wisconsin—will serve as definitive models to prove that wolf restoration

and recovery can work, contrary to the naysayers.

Speaking of models, one of the more curious stories coming out of the Minnesota

experience this year relates to the depredation statistics kept by the U.S. Department

of Agriculture Wildlife Services. The September 2001 report (covering nine months of

activity and comparing statistics with the same period from the previous year) shows a

55 percent reduction in the number of verified complaints of wolf depredation on

livestock, a 56 percent reduction in the number of farms experiencing depredation, and

a 70 percent drop in the number of wolves killed through the depredation program.

These reductions occurred following a steady increase in wolf depredations on live-

stock as the wolf population and range increased in the 1990s. While any one year

presents only a small part of the picture, Minnesota wolves appear to be defying

conventional wisdom, that is, more wolves equal more problems. A robust white-tailed

deer population may be part of the reason for the reductions, or wolf numbers may

have temporarily dropped. However, it is also nice to speculate about what other

surprises the Minnesota wolves will have for us, as we follow their intriguing story. ■

From the Executive DirectorINTERNATIONAL

WOLF CENTER

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Nancy jo TubbsChair

Dr. L. David MechVice Chair

Dr. Rolf O. PetersonSecretary

Paul B. AndersonTreasurer

Dr. Larry D. Anderson

Phillip DeWitt

Thomas T. Dwight

Nancy Gibson

Helene Grimaud

Cornelia Hutt

Dr. Robert Laud

Mike Phillips

Dr. Robert Ream

Paul Schurke

Teri Williams

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Walter M. Medwid

MISSION

The International WolfCenter supports the survivalof the wolf around the world

by teaching about its life,its associations with other

species and its dynamic relationship to humans.

Educational services and informational resources

are available at:

1396 Highway 169Ely, MN 55731-8129, USA

1-800-ELY-WOLF1-218-365-4695

e-mail address:[email protected]

Web site: http://www.wolf.org

I n t e r n a t i o n a l W o l f S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 3

Walter Medwid

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:42 AM Page 3

4 S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 w w w . w o l f . o r g

It is an impressive and unforget-table sight: 37 wild wolvesgreeting each other and play-fully romping around their

rendezvous site. Yellowstone NationalPark’s Druid Peak pack grew fromjust 8 wolves in 1999 to 27 in 2000 to 37 in 2001. This may be the largestpack of wolves ever documented.How did the pack get so big, and howdoes it compare to other large packsin recorded wolf history? We hope to answer this question, but along the way we will discuss pack size ingeneral, for it is an interesting andimportant aspect of wolf behaviorand ecology.

What determines how manywolves live in a pack is an old ques-

BIGHow Did The

Druid Peak Pack Get To Be So

?b y D O U G L A S S M I T H a n d R I C K M C I N T Y R E

W O L F P A C K S I Z E

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 4

I n t e r n a t i o n a l W o l f S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 5

tion frequently asked by wolf biologists. Arguably it is one of thefirst and most basic questions to ask.Answers presented so far includekilling efficiency, benefits of sociality,territory defense, prey size, and population density. These answers are probably not mutually exclusive;in other words, several factorscontribute both to the evolution ofwolves living in groups (families) andto the optimal size of those groups.We will not discuss all these factors in detail but reflect on a few, using theDruid Peak pack as an example.

The most basic pack structure and the kind encountered mostfrequently is a mated pair of wolvesand their pups. Average litter size forwolves in North America is about 5 or 6, so most wolf packs rangebetween 5 and 10 wolves, varyingbecause of litter size, mortality anddispersal. Larger packs build on thisbasic structure when more pups areborn in a year before all the pupsfrom the previous year die or leave.

Low mortality is one contributor tolarge packs. Protected areas, likeYellowstone National Park, wherehuman-caused mortality—often theleading type of mortality for wolves—is low will typically support largerwolf packs.

Often large packs are multi-generational, meaning that wolves ofvarious age classes live in the pack.All but one of the park’s nine wolfpacks are multigenerational, and the one was recently formed, so it is a pair with pups. Average pack size in the park is a whopping 14.6wolves/pack. Just over the parkboundary average pack size declinesto 5.8, because of higher human-caused mortality and more youthfulpacks (pairs with pups).

In addition to mortality, prey size may influence the size of packs.Early on, biologists, including AdolphMurie in 1944, proposed that wolvesneed to hunt in packs because theirprey are larger than they are:“Because wolves rely mainly on largeanimals, the pack is an advantageousmanner in which to hunt” (TheWolves of Mount McKinley, p. 45).After time and further study, this idea has gone out of vogue, but preysize may still play a role in pack size.

We now know that one wolf cankill amazingly large prey, a bison ormusk ox, for example. Murie wenton to say that if the kill is not largeenough, some wolves will go hungry,suggesting that prey size may imposelimits on pack size. We feel that prey

Chr

istop

her a

nd M

irand

a Bl

y

The Druid Peak pack of 37 wolves may be the largest pack ever documented.

Wolf #21 is the alpha male of the Druid Peak pack.

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 5

In 1998 the Rose Creek pack numbered 24wolves, 16 of which were photographed nearSlough Creek. They numbered 24 onlytemporarily as their numbers declined rapidlydue to mortality and dispersal. In 2000 the packsplit into two groups of five, and in 2001 is agroup of nine and a group of two, named theRose Creek II pack and Tower pack, respectively.

6 S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 w w w . w o l f . o r g

size may have something to do withwhy the Druid Peak pack is so large;at 37 wolves none is going hungry.

Wolves feed on prey that rangewidely in size, from white-tailed deerto moose and bison. Do pack sizesvary based on size of their main prey?The answer is, not much, but it isimportant to look beyond averages.Packs that feed on larger prey tend to be the ones that get big.

R. A. Rausch recorded a pack of 36 wolves in Alaska during the 1960s.Their primary prey was moose.Another large pack of 29 wasobserved in Alaska by Layne Adamsand Tom Meier. These wolves also ate primarily moose. Ludwig Carbynrecorded a pack of 42 wolves in WoodBuffalo National Park in northernAlberta, an area where wolves prey

predominantly on bison, but he wasnot certain that it was a single pack. It might have been an aggregation of several. He recorded five otherpacks of greater than 20 wolves,although he stated that the average inwinter appeared to be from 12 to 16.These studies and others suggest thatpacks over 20 wolves are exception-ally big and uncommon, and theirsize may be linked to the amount offood the wolves can procure.

In Yellowstone National Park theRose Creek pack reached 24 individ-uals in 1998, and their predominantprey was elk, a much smaller preyi tem than moose or b i son.Interestingly, the Rose Creek packwas not able to maintain its highnumbers very long. The packdeclined quickly after reaching itshigh count. By late 2000 it hadbroken into two packs of five, andduring spring 2001 one of thosegroups did not reproduce and hassince split up.

Part of the Rose Creek pack’sdecline may be related to theextremely large size of the DruidPeak pack. The Druid Peak pack’sterritory abuts the Rose Creek pack’s.Until the winter of 2001 the largerRose Creek pack had no troublekeeping Druid Peak wolves away, inspite of many territorial skirmishes,because since 1996 the Druid Peakpack had always numbered fewerthan 10 wolves. In 2000 the packproduced three litters of pups,burgeoning to 27 wolves—a lot moremouths to feed.

To feed that many wolves, theDruid Peak pack had to find moreelk. With its number declining, theRose Creek pack would have a hardtime defending its prey-rich territoryagainst the now much larger DruidPeak pack. Last winter that is exactly what happened: Druid Peakwolves made many raids into RoseCreek territory, some of which weobserved, and Druid Peak eventuallytook over a large chunk of RoseCreek territory. Druid Peak had

Phot

os b

y D

ougl

as S

mith

/NPS

Left: This wolf is #224, a very boldmale yearling of the Druid Peakpack. The rest of the pack hadmoved on, but he decided to do alittle exploring on his own.C

hrist

ophe

r and

Mira

nda

Bly

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 6

I n t e r n a t i o n a l W o l f S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 7

large pack maintain itself? Size of thepack is related to food abundance,which can vary because of factorsother than prey size. Prey acquisitionrate is another variable that can affectfood abundance and keep the amountof food for the pack steady enough to support it. The Rose Creek packdeclined in number probably becauseit could no longer maintain the killrates necessary to feed the entirepack. To feed its many wolves, theDruid Peak pack must increase howmany elk they feed on. We predictthat this extremely large pack, like theRose Creek pack, will not be able tomaintain its size. By mid-winter,wolves will begin leaving or dying,keeping the pack in tune with whatthe environment can support.

Will our predictions be correct?Will the Druid Peak pack split intopermanent, nonintermingling sub-groups and subdivide its territory?

found more elk to maintain its large pack. Interestingly, the threelargest packs in Yellowstone inDecember 2001, the Druid Peak (37wolves), the Nez Perce (20+ wolves)and the Yellowstone Delta (16 wolves),are making extraterritorial forays,probably trying to find enough elk toeat. The other, smaller packs arewithin their normal territories.

In April 2001 the Druid Peak packwas audacious enough to use an old Rose Creek pack den, one dug in1996 under a large boulder. TheDruid Peak wolves also denned intheir traditional den in Lamar Valley.At least 2 Druid females gave birth to 12 pups. Now the Druid Peakpack, with 5 or 6 adults, 20 yearlings,and 12 pups, numbers 37 or 38,although since we cannot always findthe twelfth pup, we count the packsize as 37 wolves. The sight of thesewolves moving across Lamar Valley is awe inspiring. We have seen this huge aggregation of wolves alltogether only once; they have beenoperating as subgroups because thepack is probably too large to functionefficiently together.

Given the idea that prey size regulates pack size, how can such a

Average pack size in Yellowstone National park is

a whopping 14.6 wolves/pack.Will the Rose Creek pack increaseagain and retake its old territory?One of the adult females in the DruidPeak pack is being picked on andcould leave, and this year the RoseCreek wolves produced at least 6 pups. These are signs of change,but we don’t know now what willhappen. This is an ongoing story—one that we are eager to follow. ■

Douglas W. Smith is project leader and biologist for the Yellowstone GrayWolf Restoration Project in YellowstoneNational Park. His many publicationsinclude The Wolves of Yellowstone,co-authored with Michael K. Phillips,a chronology of the first two years of the wolf restoration effort inYellowstone National Park.

Rick McIntyre works for theYellowstone Gray Wolf RestorationProject. He is the author of ASociety of Wolves, and the editor of War Against the Wolf: American’sCampaign to Exterminate the Wolf.

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 7

8 S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 w w w . w o l f . o r g

B Y S T E V E G R O O M S

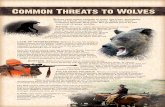

Only three decades ago, the wolfpopulation in the United States was perilously low and limited to a small

part of northern Minnesota. Wolves werefeared and reviled by those few folks who lived nearthem, and it was routine for humans to try to killany wolf they saw. When official wolf recoveryefforts began in the mid-1970s, it was not at all clearthat managers would be able to save populations ofan animal that had been systematically persecutedthroughout history.

Now wolves are thriving over a broad range inthree Great Lakes states and another broad range in the Northern Rockies. To an extent that wouldhave been unimaginable just a few years ago, peopleand wolves are managing to live near each otherwithout undue conflict.

Several laws and management programs helpedbring about this astonishing change in the status ofwolves, but the whole process was made possible bya dramatic turnabout in people’s attitudes towardwolves. One of the most hated and persecutedanimals in Western civilization is now not onlytolerated but respected, admired and even idolizedby increasing numbers of wolf fans.

Ironically, this major reversal in attitudes towardwolves carries with it new problems and new threatsto the old, troubled relationship between humansand wolves. Once wolf recovery was mostly a matter of protecting wolves from their manyenemies and their guns, traps, snares and poisons.Today wolf managers and people who admire wolveshave to worry about protecting wolves from peoplewho adore wolves and want to have a positivepersonal relationship with them.

Don’t Feed Wolves Say ExpertsB Y K E V I N S T R A U S S

This article originally appeared in the Ely Timberjay, August 18, 2001.Reprinted with permission.

Some residents of Ely, Minnesota, are concerned thatattempts by some individuals to feed wolves couldlead to serious problems, both for wolves and

humans. The International Wolf Center has receivedseveral reports of people leaving food out for wolves onboth public and private property in the Ely area. Staff havereported seeing piles of dog food, steaks, mashed potatoes,ice cream and peaches in areas where wolves have beenseen in the past.

“It is never a good procedure to feed wild wolves. By doing that you are artificially concentrating wolves inan area, and that area may be close to human habitations,”said U.S. Department of Agriculture Wildlife Services biologist Bill Paul.

Paul’s department deals with calls about nuisancewolves. Last year, he received a call about a wolf lurking ina woman’s backyard near Ely. On investigation, Pauldiscovered that a neighbor had been feeding a female wolfand her pups nearby.

According to Paul, every year his office gets a halfdozen complaints about wolves in people’s yards or wolvesthat kill dogs, and when people feed wolves close to town,those problems will only increase. “We want wolves to be

continued on page 10

Willi

am R

ideg

, Kish

eneh

n W

ildlif

e W

orks FriendsWith

Two articles offer examples of how the new

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 8

I n t e r n a t i o n a l W o l f S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 9

The accompanying two articles offer examples ofhow the new positive attitude toward wolves cancreate new problems for wolves, wolf managers andthe general public. Bill Paul’s article discusses themany unintended bad outcomes that can resultwhen people release pet wolves or wolf-dog hybridsinto the wild. Kevin Strauss’s article reports on theincreasingly troublesome practice of feeding wildwolves, concentrating them and altering theirperceptions of humans. Both practices involvemisguided sympathy that can yield deadly outcomesfor people, livestock, pets and wild wolves.

It has not been easy to craft an appropriate relationship of tolerance and respect betweenwolves and humans. That relationship continues tobe troubled, although it has changed enormously.Wolf restoration used to be a simple matter of protecting wolvesfrom their enemies.Now it requires thatmanagers protectwolves from theirfriends as well.

Steve Grooms has beenwriting about wolfmanagement since1976. He is the authorof the book The Returnof the Wolf, and serveson International Wolfmagazine’s advisorycommittee.

Releases of Tame Wolvesand Hybrids Give WildWolves a Black EyeB Y B I L L P A U L

The U.S. Department of Agriculture Wildlife Servicesprogram in Minnesota is responsible for resolvingconflicts that occur between wolves and livestock,

and wolves and humans. That job is difficult enoughwithout the added burden of dealing with illegal releases of tame wolves and wolf-dog hybrids within Minnesota’swolf range. Usually, people release tame wolves or wolf-doghybrids for either of two reasons: the animal or animalsbecome too difficult for the owner to handle or care for, orthe owner mistakenly thinks that these tame wolves or wolf-dog hybrids may be successfully released into the wild to

survive on their own or to join up with wild wolves.The truth is that these misguided, illegal releases

benefit neither the animals released nor wild wolves.Tame wolves and wolf-dog hybrids that are releasedinto the wild are very likely to gravitate to human-occupied areas, kill livestock or pets, and exhibitunusual or bold behavior because they have beenraised in captivity and are habituated to people.When these animals show up at farms or in people’syards, they are often mistaken for wild wolves, andtheir bold or unusual behavior may raise serioussafety concerns among people.

For example, a group of 8 to 10 wolf-dog hybrids(including both adults and pups) was released in theTower area in early September 2001. Wildlife Services

continued on page 11

Like These...

Wolves have been fed bypeople in the Ely area, andwolf-dog hybrids werereleased near Tower,Minnesota.

positive attitude toward wolves can create new problems for wolves.

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 9

10 S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 w w w . w o l f . o r g

as fearful of humans as possible to minimize conflictswith humans and domestic animals,” said Paul.

In national parks, many habituated bears must bedestroyed to prevent conflicts between bears and parkvisitors. Because of this, park staff teach visitors theadage that “a fed bear is a dead bear” to remind peoplenot to feed wild animals. The same might apply towolves, say wildlife officials here.

Possibly because of the feedings, some of the wolvesin what researchers call the Farm Lake pack, living east of Ely, have lost their fear of cars to such an extentthat people are seeing them standingout on the Fernberg Trail roadway.“The biggest danger is to the wolves,not the people,” said Kawishiwi Field Lab wildlife research biologistMike Nelson. According to Nelson, wolves who see carsas a source of food are much more likely to be hit on the highway.

“The state discourages the public from feeding wildanimals, and wolves would be no different. There haven’tbeen any problems with wolves attacking people in thearea. They have killed livestock and pets in the area,though,” said Nelson.

At least one resort on the Fernberg Trail is seeingmore wolf activity. According to Kawishiwi Lodgemanager Harry Homer, two weeks ago, three resort

visitors reported seeing a wolf near their cabins. TheKawishiwi Lodge cat disappeared at the same time.

“I’m not sure that people in the Ely area want wolvesto learn to associate humans with food,” said AndreaLorek Strauss, information and education director forthe International Wolf Center. “People empathize withwild animals, which is fine, but when they try to help by putting out food or even in some cases rescuing(supposedly abandoned) wolf pups, they aren’t doingthe animals any favors,” she said.

According to Strauss, about 50 percent of wolf pupsstarve every year. If this didn’t happen, we would soonhave an overpopulation of wolves in the area.

According to Paul, people who are feeding wolvesaren’t the only ones who are luring wolves into closercontact with humans: “When people are feeding deer intheir backyards in the winter, they create artificial winterdeeryards, and that brings in wolves close around town. That increases the chances for conflicts and doesa disservice to wolves.”

Kevin Strauss is a nature writer and storyteller who lives inEly, Minnesota. He is currently working on a CD of wolf storiesand a book of traditional wolf stories from around the world.

When people feed wolves close to town, conflictswith humans and pets will only increase.

Possibly because of feedings,this Farm Lake pack pup andits pack mates lost much oftheir fear of cars and people.

Feeding Wolvescontinued from page 8

Lynn

and

Don

na R

oger

s

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 10

received several calls from a cluster of rural Tower residents reporting that “wolves” were coming into theiryards, up onto their porches or decks, and hangingaround their homes day after day. One resident’s dog waskilled by the “wolves,” and several residents expressedconcern for human safety because of the boldness of the“wolves,” which seemed oblivious to human harassment.

Wildlife Services personnel responded to thecomplaints and were able to shoot two of the animals,which were determined to be wolf-dog hybrids. Thephysical appearance of some of the animals was verywolflike (perhaps 3/4 wolf), which explained why peoplethought they were wild wolves. However, the animalsalso had some dog or captive animal characteristics,such as short stocky legs, a three-quarter-length tail, andunfurred ear tips. All of the animals were also a distinc-tive blondish red. In addition to the two animals that

were shot, two others were trapped and destroyed. Thetaking of the four wolf-dog hybrids caused theremaining animals to move away from the area wherethey had settled. It is unclear whether they survived.Some of the adult animals may disperse to other areasand cause additional problems. Obviously, this illegalrelease benefited neither the animals released nor thepublic’s perception of wild wolves.

A large group of tame wolves and wolf-dog hybridswas also released during winter 1996-97 in theBarnesville Wildlife Area about 25 miles southeast ofMoorhead. At that time, that location was welloutside of the established wolf range in the state.During summer 1997 and 1998, these animalscaused livestock depre-dations at three farms inthe Rollag area. Severalcalves were killed orwounded at the farms,and Wildlife Servicespersonnel removed twoanimals that were deter-mined to be tame wolves

I n t e r n a t i o n a l W o l f S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 11

because they were captured in close association withfour other animals that were clearly wolf-dog hybrids.

Because two of the animals looked like wild wolves,the affected farmers as well as state and federal personnelwere confused as to whether the farmers would beeligible to receive wolf compensation payments for theirlosses or whether they could legally shoot any remainingproblem animals. There was also public speculation thatwild wolves had crossed with dogs in that area andproduced the hybrids. In 25 years of wolf control acrossMinnesota’s wolf range, Wildlife Services personnel havenever documented a situation where a wolf has bred with a dog in the wild and produced offspring. Mostencounters between wolves and domestic dogs result in injury or death to the dog.

Wildlife Services personnel also removed a singlewolf-dog hybrid during October 2001 from a populatedarea on the southeast side of Pelican Lake, north ofBrainerd. That animal was coming into people’s yards,feeding out of dog dishes or garbage, and was observed

following people or their pets.During June 2000, two wolf-doghybrids were removed by WildlifeServices personnel at a rural residence near Remer. They cameinto a resident’s yard multiple times

and approached the resident’s dogs. Since the residenthad a day-care operation, the boldness of the animalsraised strong concerns about human safety.

A substantial number of people in the United Statesown tame wolves or wolf-dog hybrids, often legally but sometimes illegally. Should these animals become aproblem, their owners should never attempt to releasethem into the wild. The likelihood of tame wolves or wolf-dog hybrids surviving in the wild is low, their potential forconflict with humans is great, and their actions often givewild wolves a black eye. ■

Bill Paul is the Assistant StateDirector for the U.S. Departmentof Agriculture Wildlife Servicesprogram in Minnesota, where he coordinates federal wolfdepredation control activities. He has been involved with wolfresearch and control programs in Minnesota for 25 years.

The likelihood of tame wolves or wolf-dog hybridssurviving in the wild is low; their potential forconflict with humans is great.

The physical appearance of somewolf-dog hybrids, like this female to the left, is very wolflike.

Release of Tame Wolves and Hybridscontinued from page 9

ww

w.w

olfp

hoto

grap

hy.c

om

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 11

World Press Institute Visits the International Wolf Center

12 S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 w w w . w o l f . o r g

INTERNATIONAL WOLF CENTER

Notes From Home

As always, the International Wolf Center is honored

to host visitors from all over the world. This past

year, the largest group was journalists who participated in

the annual World Press Institute program (WPI is located

at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota). Participants

came from Brazil, the Czech Republic, China, India, Mexico,

Pakistan, the Philippines, Poland, Romania and Uganda.

For several years, the trip to Ely has been part of the annual

WPI program, which brings news professionals to the

United States to visit media in cities throughout the country,

government agencies in Washington, D.C., and farms

and sites in the Midwest.

Hosted by the Ely Echo, participants visited the

International Wolf Center as part of their educational

and cultural experience. Milt Stenlund, renowned wildlife

biologist and wolf researcher, delivered a special presenta-

tion, and Program Specialist Jen Westlund

gave the visitors a closer look at the

ambassador wolves in a Behind the Scenes

program. Ann Swenson of the Ely Echo

said that after four months of travel and

study around the country, participating

journalists invariably report that the visit

to Ely was a highlight of their experience in

the United States.

Earlier this year LizHarper, International

Wolf Center informationspecialist, visited SonnesynElementary school in NewHope, MN and presented

Children Send Thanks for Wolf Programa wolf program to Thirdgrade students. The Centercontinues to present pro-grams to schools and otherinterested groups throughoutthe nation.

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 12

★I n t e r n a t i o n a l W o l f S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 13

Alpha Weekend 2001: Running with Wolves, Walking with Bears

International Wolf Center Receives Conservation Award

The International Wolf Center is the winner of the first

annual Smithsonian Magazine/USTOA Conservation

Award. The award from Smithsonian magazine and

the United States Tour Operators Association’s (USTOA)

Travelers Conservation Foundation recognizes an

individual, organization or destination in the travel or

tourism industry that has committed to preserving the

environment and its resources. Walter Medwid, the

Center’s Executive Director, accepted the award of $25,000

on behalf of the organization at the USTOA Annual

Conference in Miami on December 4. “We are honored

to receive this award for the Center’s wolf conservation

efforts.” said Medwid. “Human misunderstanding has

plagued the wolf for centuries. It’s our educational mission

to present the facts and debunk the myths, creating a world

where wolf populations thrive in native lands and where

human needs are balanced with an acceptance of the wolf’s

presence. The enthusiastic interest and participation by

children and adults in our programs gives us hope for

the survival of wolf populations around the world.” ■

Left: Lauri and Rick Coffman, Alpha Legacy members from Reinbeck,Iowa, sighting wildlife on the 2001 International Wolf Center membershipappreciation weekend.

Executive Director Walter Medwid and board member Neil Hutt hold the$25,000 check received from the Smithsonian Magazine/USTOA.

Inte

rnat

iona

l Wol

f Cen

ter

Nan

cy jo

Tubb

s

Offered as a specialappreciation to Alpha,

Alpha Legacy and WolfSponsor members, “TheA l p h a M e m b e r s h i pAppreciation Weekend”provides International WolfCenter members with aninsider’s look at the work-ings of the Ely interpretivecenter and Minnesota’snorth woods. This year’sprogram included an “upclose and personal” intro-duction to the residentpack, with an overview ofpack behavior and healthand plans for enclosureimprovements, a guidedback-count ry out ingfeaturing a traditionalBoundary Waters “walleyeshore lunch,” and sightingsof eagle’s aeries, loons andwild wolf pups. In a hands-

on demonstration of radiotelemetry tracking, memberEllen Dietz of Bloomington,Illinois, was rewarded forher persistence, picking upsignals from a recentlycollared wild wolf in thevicinity. Bear biologist andfriend of the Center LynnRogers welcomed membersto a tour of his researchstation and an introductionto the wild resident bearsand cubs that roam hiswilderness retreat. “Thiswas really a once-in-a-life-time experience,” acknowl-edged Lauri Coffman ofReinbeck, Iowa. “Good,then perhaps we will haveeven more Alpha and WolfSponsor members to shareit with next year,” repliedCenter Associate DirectorMary Ortiz.

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 13

14 S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 w w w . w o l f . o r g

Major DonorsClaire Atkins

Dorothy Blair

Catherine Brown

Robert Carlson

Lammot Copeland Jr.

Thomas & Helen Dwight

Lynn Eberly

Evelyn Fredrickson

Barbara and Lewis Geyer

Neil Hutt

Amy Kay Kerber

Robert Laud

Brian Malloy

Dave Mech

Thomas Micheletti

Rolf and Candy Peterson

Sarah Morris

Yvonne I. Pettinga

Sherry Ray

Paul Schurke

Helen Tyson

John and Donna Virr

Matching GiftsLauren and Rick Coffman &GMAC Mortgage

Frances Cone & ING Foundation

Anthony Luksas & Tootsie Roll Industries, Inc.

Michael McPhillips & Philip Morris Companies Inc.

Kevin Oliver & United Way of Orange County

Antonie Parker & Benjamin Moore & CO.

HonoraryIn Honor of Neil Hutt and their 40th Anniversary:

Tom Hutt

In Honor of Greg & Diane Lake:

Mary Beth Lake

In Honor of Tina McDonald & Richard Ray:

Hans Gulbe

In Honor of Larry Stoehr Jr’s Birthday:

Larry & Sylvia Stoehr

RoyaltiesMBNA America Bank, NA

RYKODISC, INC.

Tom Speros Tree FundBen Agar & Julee Caspers Agar

Ron Harshman & Teri Williams

MemorialsIn Memory of Ralph Bailey:

Mr. and Mrs. Michael Cameron

In Memory of Jeffrey Hausmann:

Chris & Joan Hausmann

In Memory of Linda Salzarula:

Carolyn Pilagonia

In Memory of Nesbit Siekkinen:

Sheila and Bruce Sanders

Major Grants and AwardsElmer and Eleanor AndersenFoundation

David and Vanessa DaytonRevocable Trust

Mary Lee and Wallace Dayton

Nancy Gibson and Ron Sternal Challenge Grant

Casey Albert T. O’NeilFoundation

Smithsonian Magazine/USTOA Conservation Award

Southern Rockies Project

Target Stores

In-Kind DonationsBill & Diane La Due

Mare Shey

Kim Wolfgram Salz

Wolf EnclosureDonationsBarbara Chance

INTERNATIONAL WOLF CENTER

Contributors

Thank You!

Travel the protected waters ofSE Alaska’s inside passage.This remote area of mountainous islands, old growth timber and tidal estuaries is home of theAlexander Archipelago Wolf.

6 day, 5 night trips, meals,lodging, daily shore excursionsinto the best wolf habitat.

FOR A BROCHURE CONTACT:

Riptide OutfittersP.O. Box 19210

Thorne Bay, Alaska 99919

www.hyakalaskacharters.com907-828-3353

Wolf Watch Aboard the

MV HYAK

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 14

the Center’s Web site (see www.wolf.org) haveoften observed one of theambassador pack membersstanding on a rock in a regalpose. Additional bouldersand rocks were added to theenclosure, allowing eachwolf to have a rock to claim.As an added stimulus, westacked three rocks on topof one another to provideravens a spot to perch.Malik and Shadow appearto be mesmerized by ravens.

To complete this projectwith minimal disruption tothe wolves, a temporaryfence was installed to keepthe wolves in the back oftheir wooded enclosure.Malik was most curious,while Shadow was a bitmore fearful, but each spenttime watching the move-ment of the contractors andtheir equipment. Mackenzieand Lucas took advantageof Shadow’s intimidationand asserted their domi-nance over their youngerpack member, who usuallyresisted theirefforts. Lakotaspent the timetrying to avoidthe redirectedw r a t h o fShadow. Onone evening,s h e s o u g h trefuge in the

Tracking the Pack

construction site by diggingunder the temporary fenceand spending the night with the backhoe.

While these improve-ments to the enclosure willcertainly enhance thewolves’ physical envi-ronment, wolf care

staff are equally enthusiasticabout the psychologicalstimulus these features willprovide to the pack.

Thanks to a l l whosupported this project. ■

As northern Minnesota residents prepared for winter, the

International Wolf Centerwas preparing for nextsummer. No, we didn’t havethe wrong month on thecalendar; we were taking theopportunity of the slower fall season to improve theCenter’s wolf enclosure byconstructing a new rockoutcrop den and a two-tierpond system with a waterfall.

The new den measures56 square feet and has twoentrances. This will provideLakota (the bottom-rankingwolf) a place to take refugefrom the exuberance of the younger pack members,Shadow and Malik. Thepond system consists of anupper pond measuringapproximately 96 squarefeet, a lower pond, whichcovers approximately 500square feet, and a 20-footraceway, which connectsthe two ponds. The lowerpond has a maximum depthof 3 feet, allowing thewolves to take a swim onwarm summer days.

Researchers observingwild wolves have noticedthe tendency of wolves touse high vantage points tosurvey their surroundings;the Center’s captive wolvesare no different. Visitors tothe Center and viewers of

The Pack Gets a Pondb y L o r i S c h m i d t , W o l f C u r a t o r

I n t e r n a t i o n a l W o l f S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 15

Malik watching Aaron Luestek of Luestek Construction working on the den site.

Lucas and Shadow (the white wolf)take a swim in the new pond.

And

rea

Lore

k St

raus

s

Nan

cy jo

Tubb

s

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 15

16 S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 w w w . w o l f . o r g

survive, he may be able tofind a female disperser,mate, and form a new pack.

Months pass after thedisappearance of #18’ssignal. Then in October2001, a farmer in northernMissouri returns home frombow hunting. Seeing whathe assumes is a coyote nearhis sheep pen, he nocks anarrow and shoots theanimal. After discoveringthe collar and numbered ear tag, the farmer takes the body to MissouriConservation Departmentofficials, who verify theanimal is indeed an 81-pound gray wolf. It is #18.

A glance at a map revealsthe difficulty of #18’sincredible journey. Roughly450 miles as the crow flieslie between his capture sitein northwestern Michiganand Grundy County,Missouri. The distance itselfis not without precedent.Biologists believe wolvestravel farther than any otherterrestrial mammal, andmany accounts have beenv e r i f i e d o f w o l v e sdispersing hundreds ofmiles from their birthplace.

What makes #18’sodyssey so remarkable is, inHammill’s words, “the typeof terrain and the obstaclesthis animal had to circum-

The movement down thetrail would seem relentlessif it did not appear so effort-less. The wolf’s body, fromneck to hips, appears tofloat over the long, almostspindly legs and the flickerof wrists, a bicycling driftthrough the trees, reminis-cent of the movement ofwater or of shadows.— Barry Lopez, Of Wolves and Men

It is July 1999. NearIronwood in north-

western Michigan, biologistshave caught a young malewolf weighing a hefty 22pounds. They ear tag the bigpup and attach a radiocollar lined with foamrubber to ensure a comfort-able fit as the pup grows.Jim Hammill, MichiganDepartment of NaturalResources (DNR) biologist,

hopes the collar will remainintact long enough forresearchers to locate thepup’s littermates.

The young wolf’s collarsurvives the rigors ofpuppyhood, and for ninemonths, Michigan DNRbiologists are able to followhis movements. Then theylose track of him. If #18 hasstruck out on his own, hisdefection from his natalpack is not unusual, but it is risky. Hunting is difficultfor a lone wolf, and if theyoungster trespasses on the territory of another wolfpack, he is in danger ofbeing injured or killed.Nevertheless, if food isavailable and he can

Inte

rnat

iona

l Wol

f Cen

ter

b y N e i l H u t t

W O L V E S I N T H E U N I T E D S T A T E S

Michigan to Missouri: TheIncredible Journey of Wolf #18

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 16

I n t e r n a t i o n a l W o l f S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 17

T H E W O L V E S O F AY L M E R L A K E ,N O R T H W E S T T E R R I T O R I E S ,C A N A D A

Whereaboutsof Female andPups a Mystery

This past August, theInternational Wolf

Center sponsored a trip toAylmer Lake, a remote desti-nation near the Arctic Circlein Canada’s NorthwestTerritories. The groupposted daily reports andphotographs of this fasci-nating landscape and itswildlife on the Center’s Website (“Notes from the Field”at www.wolf.org). This online journal provides botha vicarious adventure forwolf fans everywhere and an insight into the patienceand persistence required bybiological fieldwork.

A similar group makingthe same trip in August2000 had been extraordi-narily lucky. From a hidden

vantage point behind aboulder spill, the groupwatched the Aylmer Lakepack’s rendezvous site. Theyenjoyed the rare sight of 9adult wolves going aboutthe business of raising 15pups—playing with them,heading out to hunt, joiningtogether in group howls,and bringing food to thefast-growing youngsters.

The August 2001 groupencountered a radicallydifferent set of circum-stances. Mysteriously, theysaw no wolves at the oldrendezvous site. While theydelighted in spotting theradio-collared breedingmale and several yearlingsat random locations, theysaw no trace of the breedingfemale and the three-month-old pups on theopen tundra, even with theaid of aircraft.

Trip leader Dave Mechand Canadian biologistDean Cluff were mystified.

The Aylmer Lake pack withfive or six pups had beenseen at the den site asrecently as June. Accordingto a local observer, theradio-co l lared femaleshowed up occasionally atthe den in July and earlyAugust. But in mid-August,the female and the pupswere nowhere to be found.

After a week of diligentsearching, the Center’sgroup reluctantly left theregion, still pondering thefemale’s whereabouts. Hadshe left the area and traveledtoo far for her radio signalto be picked up? That ispossible. The pups were oldenough to travel providedthe mother could hunt andsupply them with food. Butthe research plane rangedlong distances in everydirection without pickingup her signal.

Was the female’s radiocollar malfunctioning?

vent.” The wolf had to crossthe Mississippi River andthread his way across thelabyrinth of highways thatstrangles much of theregion. “You have to wonderhow many people saw thisanimal along the way andeither kept it to themselvesor told people and weren’tbelieved,” said MichiganDNR biologist Dean Beyer.

Reflecting on #18’sincredible journey, MissouriConservation Departmentwildlife research biologistDave Hamilton concededthat the likelihood of seeinga gray wolf in his state isstill small. However, #18’sjourney demonstrates yetagain that wolves arecapable of great feats ofendurance. “For years, webelieved and told peoplethat there were no wildwolves in Missouri,”Hamilton admitted. “Wecan’t say that anymore.”

Kath

y Re

bane

The Aylmer Lake pack had beenseen at the den as recently asJune, as had five or six pups.

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 3:08 PM Page 17

18 S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 w w w . w o l f . o r g

Mech and Cluff consideredthat unlikely. The collars aredurable, and the batteries inthe transmitter were rela-tively fresh. In addition, thebreeding male was alwaysobserved alone or with thejuveniles. Even if the femalehad remained in the areawith a nonfunctioningcollar, chances are good that someone would havespotted her or the pups.

Was the mother dead?Mech and Cluff concludedthat was possible but alsounlikely. Biologists neverheard a mortality signalfrom the transmitter on

her collar, a rapid beep indicating she had notmoved for a long time.

Canadian researcherscontinued the air search inAugust and Septemberwithout locating the AylmerLake female. The flightsproduced a puzzling obser-vation: low pup numbersseemed to be widespreadthroughout the region.

Cluff i s evaluat ingseveral factors that mighthave hampered the biolo-gists’ ability to find pups.The ground was mottled

Journey by Horseback Through Wolf Habitat Deep in theHeart of the Idaho Wilderness

•One night hotel stay, with meals

•Base camp in the wilderness with canvas cooktent and individual pop-up tents to sleep in for privacy.

•Fully prepared home cooked meals

•Trips begin in mid-July and end in late August

Mile High Outfitters of Idaho, Inc.P.O. Box 1189, Challis, Idaho 83226(208) [email protected] our webpage at

www.milehighwolf.com

from early snowfall, soobservers might havesimply failed to spot somewolves that were present.

If, however, pup produc-tion or survival was poorthroughout Cluff ’s studyarea, the question becomes,Why? Since caribou arrivedunusually late in the regionnear many of the area’s den sites, some pups mayhave starved. “Still,” saidCluff, “adult wolves arequite mobile, and surelythey could still encountercaribou, some of which theycould kill for food.”

Perhaps next summerwill yield a solution to the puzzle when anotherCenter group travels to theNorthwest Territories. Untilthen, the answer to theriddle of the Aylmer Lakefemale and her pupsremains locked in thewinter darkness and brutalcold enveloping the vasttundra.

Caribou is the main prey species of the Alymer Lake pack.

Trist

an R

eban

e

Ala

n Re

bane

Visit Alymer Lake with Dave Mech

and the InternationalWolf Center!

SEE BACK COVER FOR DETAILS.

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 18

I n t e r n a t i o n a l W o l f S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 19

Wav

erle

y Tr

aylo

r

Kurt, Bozcurt, Canavar,Bocu—each of these

four local Turkish namesmeans “wolf,” a specieswhose numbers have beendeclining in Turkey sincethe 1980s. Mortality hasincreased for all the reasons common elsewhere:large-scale habitat degrada-tion, intraspecific competi-tion, decrease in the prey base and direct humanpersecution.

Emre Can of WWFTurkey (The Turkish Societyfor the Conservation ofNature) studied wolves in2000 and 2001, and collecteddata on distribution, prey,conflicts with humans, and conservation andmanagement practices. Hereported an estimated 7,000to 11,000 wild wolves livingmainly in the centralportion of the country, aland of forests and steppeswhere the wolf ’s major prey are wild boar, roe deerand hare.

The main causes of thewolf’s decline in Turkey areh u n t i n g a n d d i r e c t persecution by humans.The Turkish governmentconsiders the wolf a pest,and although no organizedhunts are conducted, localpeople shoot wolves when-ever they encounter them.Trapping has also long been a traditional methodfor killing wolves. The availability of poison sincethe 1960s has made this

efficient exterminationmethod widespread as ameans of predator control.Even the Ministry ofForestry freely used poisonin different regions ofTurkey and recommendedits use, according to Can.However, at present, poisonis not used as widely as itwas before the 1980s.

Wolves are hunted fortheir pelts in Turkey, butlivestock depredation,mainly of sheep and cattle,is the main reason wolvesare killed. In addition,people living in rural areasfear they will contract rabiesfrom wolves. According toCan’s report, little reliableinformation exists on thissubject. The Ministry ofHealth in Turkey hasreported very few cases ofrabies in which the in fec t ion source was

believed to be wolves. Canobserved, however, thatstatistics were not properlykept, and the real figureswere probably higher.

At present, wolves inTurkey are not legallyprotected. Under the 1937Turkish Land Hunting Law,the wolf is listed as a pest; itcan, therefore, be huntedthroughout the year with no limitations. Can said anew hunting proposal ispresently before the Turkishpar l i ament . In Can ’sopinion, however, theproposal is inadequate, andWWF Turkey has suggestedspecific modifications.

According to the CentralHunting Commission andto Forest Law, hunting is forbidden in national parks, production forests,protected forests and gamebreeding areas. While it isillegal to hunt wolves inthese areas, the areas aregenerally too small to beadequate refuges for wolves.

Can reported that Turkeyis preparing for a country-wide survey involving 1,500local forestry offices. Theresults will be analyzed andcompared to the currentinformation available onnumbers and distribution of wolves in Turkey.

Relative density of wolf population in TurkeyMap courtesy of: Ö. Emre Can, WWF Turkey

W O L V E S I N T U R K E Y

Wolf Population Declines

Higher wolf density Low wolf density

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 19

20 S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 w w w . w o l f . o r g

in summer 2000,a p ioneer ing ecotourism grouporganized byInternat iona lWo l f C e n t e rboard memberPaul Schurkeand h i s wi f e ,Susan, discovered the tracksof two wolves. Ovsyanikovhoped a breeding pair hadmigrated across the 100miles of sea ice from theS iber ian main land toWr a n g e l . I f t h e p a i rproduced pups, perhapswolves could recover ontheir own. Researcherswould then be able to divertmoney earmarked for wolfreintroduction to other critical needs of this eco-logically sensitive area(International Wolf, Summer2001).

In summer 2000, Russianb i o l o g i s t N i k i t a

Ovsyanikov discovered thetracks of two wolves onWrangel Island, the 5,000-square-mile arctic wildlifereserve located off thenortheastern coast ofSiberia. Although WrangelIsland’s terrestrial andmarine ecosystems containan extraordinary concentra-tion of wildlife, the wolf has been missing for 30years since being extirpatedby the Soviet government to protect the musk oxenand reindeer.

Since money to protectRussia’s nature reserves hasrecently all but disappeared,Ovsyanikov has looked for sponsors to fund hisresearch and to reintroducewolves to Wrangel Island.Thus, he was elated when

In December 2000, freshwolf tracks were discoveredon the island near a herd ofreindeer. Then in April2001, personnel at a fieldresearch station found onewolf track.

Ovsyanikov returned toWrangel Island in summer2001, hoping to discover abreeding pair with offspring.However, neither he noranyone else found anyevidence that wolves mightbe present. Ovsyanikov wasdisappointed but notdiscouraged. He noted that

during his stay on Wrangelhe was unable to travelaround the island in searchof wolves as much as hewould have liked. Also, themain herds of reindeer wereconcentrated a considerabledistance from the fieldstation.

Ovsyanikov said his lackof success in finding wolftracks could mean one ofseveral things. One wolf mayhave died, and the other mayhave left the island. It is alsopossible that neither wolfsurvived. Rabies is common

To protect the musk oxen and reindeer, the Soviet government extirpated thewolves on Wrangel Island 30 years ago.

W R A N G E L I S L A N D U P D A T E

Survival of Wolves Still Uncertain

Nik

ita O

vsya

niko

v.

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 20

Nik

ita O

vsya

niko

v.

I n t e r n a t i o n a l W o l f S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 21

among arctic foxes, and thewolves may have contractedt h e d i s e a s e . P e rh a p s ,Ovsyanikov speculated, bothwolves left the island;however, he considered thatunlikely.

Ovsyanikov still holdsout hope that both wolvessurvived and produced pupsin spring 2001. Maybe, he said, they hid duringsummer from places visitedby humans. Reindeer wereheavily concentrated on the remote western portionof Wrange l , a reg ionOvsyanikov called NamelessMountains. It is also possiblethe wolves raised their pupsin eastern Wrangel Island,where large herds of reindeermoved in spring 2001.

“I think if wolves are onthe island, they will show

themselves, or at least signsof their presence, during thenext spring,” Ovsyanikovsaid. “If we don’t find anytracks during the nextspring-summer season,then we may say for surethat wolves disappearedfrom the island.”

If that disappointingpossibility becomes a reality,Ovsyanikov will revisit theplan to reintroduce wolvesto Wrangel Island. “But thisaction will require adequatefunding,” he said. That mayprove to be the mostdaunting impediment of allto the return of the wolf tothis arctic Eden. ■

Neil Hutt is an educator andInternational Wolf Centerboard member who lives inPurcellville, Virginia.

What is the average litter size of the wolf?Litter sizes vary, but an average litter size for gray wolvesis six, and for red wolves is four to five. If natural prey isnot readily available, several pups may die. A wolf packnormally has only one litter of pups each spring, but inareas of high prey abundance more than one female ineach pack may give birth. ■

How many states in the U.S. currentlyhave known breeding packs of wolves?

New QuestionLy

nn a

nd D

onna

Rog

ers

www.wolf.orgVISIT

www.wolf.orgTODAY!

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 21

22 S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 w w w . w o l f . o r g

It was 1:30 in the morning as LisaBelmonte and I stood on theabandoned railroad grade, hoping

to hear a boreal owl.Lisa, a graduate student at the

University of Minnesota–Duluth,had just begun studying boreal owlsunder a grant from the MinnesotaDepartment of Natural ResourcesNongame Wildlife Program. BecauseI had studied boreal owls in the same area 10 years ago, I offered tohelp her get started. Two nightsbefore, she had heard a boreal owlsinging from this remote spot nearthe edge of the Boundary WatersCanoe Area Wilderness, and wehoped to relocate it.

No moon illuminated the darkwoods, but the silhouette of thesurrounding trees stood in starkcontrast to the canvas of a night skypierced by countless stars. Beneaththe trees, darkness reigned; I couldn’tsee Lisa standing 10 feet away. Not a breath of wind swayed the trees,and our ears strained against theimmense silence of the night.

Crack!The sound of a large branch snap-

ping a couple hundred yards awayfilled the night. Not an unusualsound on cold winter nights whenmoisture in the wood freezes andexpands. Tonight was relatively mild,though, in the mid-20s—much toowarm for that phenomenon. Moose, Iimmediately thought.

“What was that?” Lisa whispered.“Bigfoot,” I replied.“It was not!” she said, her voice

betraying just a hint of nervousness.Moments later, similar noises

from the same direction and distanceseemed to confirm my first impres-

This article originally appeared in the Jan.–Feb. 2001 issue of Minnesota ConservationVolunteer, bimonthly magazine of the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Reprintedwith permission.

Close Encounters –A Night to RememberThe mystery of things that go bump (crash, thud, rumble, crunch, and pant) in the night.

b y S t e v e W i l s o n

I l l u s t r a t i o n s b y R o b e r t B o w m a n , C o t t a g e G r o v e , M i n n e s o t a

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 22

I n t e r n a t i o n a l W o l f S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 23

sion. Unlike deer and wolves—the other large mammals wanderingthe north woods in winter—mooseare not known for their stealth.

Still, as we continued listeningand the noises got louder and closer,I found myself puzzling over what we were hearing. Something wasn’tright. I’d heard my share of moosepassing in the night, and they tend to do just that—pass by. Pausing tofeed, they typically make some noisewhile breaking off smaller twigs toeat, but nothing like what we werehearing.

This animal made a tremendouscommotion from one spot, thenmoved on, sometimes quickly, asevidenced by the rapid crunch-crunch-crunch of its hooves in thecrusty snow. It didn’t travel far,though, before stopping and seemingto thrash violently about, sometimesfor minutes at a time.

After one such bout, I heard Lisa’svoice from behind me, more insistentthis time: “What was that?”

“Bigfoot,” I said, good-naturedlytaking advantage of her admitteddiscomfort with the north woods atnight.

The noises—and whatever wasmaking them—approached, growinglouder still. I briefly imagined ananimal harried by wolves butdismissed this as too improbable;more likely it was a poor beast infectedwith brainworm, a parasite that canrender an adult moose incapable ofcontrolling its movements.

“Did you hear that?” asked Lisa.“Hear what?”“A boreal owl, behind us!”I hadn’t, which I attributed to the

growing racket from the woods infront of us. To the sounds of branches

breaking and hooves crunching andthudding, add an occasional loud,low, rumbling exhalation. Clearlythis was not your normal moose-going-for-a-walk-in-the-woods.

“He sounds angry,” I whispered to Lisa.

Whatever was out there was closernow—maybe 50 yards away. Mysenses were alert, straining for cluesto the nature of the event unfoldingin front of us. The rumbling, snapping, cracking, thudding, andcrunching moved by us and ontothe old railroad grade, perhaps 50yards away. The sound of thuddinghooves and heavy breathing thenturned and moved toward us.

At that moment my ears detecteda new sound—heavy panting, not ofone animal, but several. Wolves! Inan instant it all made sense—wolvesharry the prey until it turns andstands its ground, violently whippingaround to keep from being flanked,then breaking and moving again—until forced to make its next stand.

“Steve, let’s move over to thetruck!” Lisa whispered anxiously, as she too realized what wasapproaching.

I didn’t respond but stood trans-fixed in the middle of the road, unableto believe what was happening. I didnot budge or say anything for fear of interrupting the drama.

“Steve!” Lisa said as loud as shecould whisper, as she backed out ofthe middle of the road.

By the relative strength of thewolves’ panting and moose’s laboredbreathing and clumping footsteps, I guessed the wolves were on theheels of or trotting beside the moose.My eyes strained at the darkness, tono avail. I relied entirely on my earsto judge the distance from me to theclosing moose and wolf pack.

Thirty, 20, 10 yards, and still theydidn’t veer off. The rush of soundsfilled the night when I thought, now!and reached for the switch on myheadlamp. For a moment that seemedan eternity, the switch balked. Ithought to jump aside but notknowing which way to go, I appliedsome adrenaline-assisted pressure tothe switch. On came the light, andthere was the moose—not 10 feetaway, and heading straight for me,head down, eyes glazed, its gait and

Clearly this was

not your normal

moose-going-

for-a-walk-in-

the-woods.

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 23

24 S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 w w w . w o l f . o r g

breathing hinting at the lengthand gravity of its struggle. I quickly sidestepped as itpassed by at no more thanarm’s length, completely oblivious to me. I swept thelight, but the wolves hadvanished, except for thesounds of twigs snapping and footfalls crunching lightlyin the snow. We listened untilwe could hear nothing more.

“My legs are shaking!” Lisaexclaimed, not in fear, but intotal excitement. I was still in awe of how closely we’dwitnessed a life-and-death drama. We compared notes and our mutualdisbelief at what we’d experienced,barely acknowledging another briefburst of staccato song from the boreal owl.

After we’d calmed down, Lisasuggested we howl to see if the wolves would respond. We did, andalmost immediately elicited a beau-tiful symphony of howling fromdown the grade. Figuring the packwouldn’t have taken time to respond

if still in pursuit, we guessed they hadbroken off the chase.

Apparently the moose hadsurvived—for a time, at least. Lisa,formerly a wolf researcher, admittedher sentiments had been with thepredator, and she expressed milddisappointment that we had changedthe outcome. I searched my ownemotions. As an ecologist I know thatmost species are sustained by thedeath of others. But then, recalling thedesperate look in the moose’s eyesand realizing the wolves would haveanother chance, I found myself notregretting the role we had played. ■

Steve Wilson is a scientific and naturalareas specialist for the MinnesotaDepartment of Natural Resources.

My ears detected

a new sound—

heavy panting,

not of one animal,

but several. Wolves!

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 24

I n t e r n a t i o n a l W o l f S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 25

KEEPERS OF THE WOLVES,

by Richard P. Thiel, is a new 227-page book (University of WisconsinPress 2001, $50 cloth, $19.95 paper)discussing the early years of wolfrecovery in Wisconsin. With linedrawings and written in first person,this is a very readable book.

WOLVES AND SNOWMO-BILES in Voyageurs National

Park are in the news again. The park, after a decade of prohibitingsnowmobiles in certain bays toprevent them from interfering withwolf activity, has rescinded its ban.Studies were unable to show a signif-icant effect of snowmobiling on thewolf population. This result is inaccord with an International WolfCenter survey of wolf biologistspublished in the spring 1992 issue ofInternational Wolf.

WO L F 3 4 M D E A D . Thisbreeding male of Yellowstone

National Park’s Chief Joseph pack wasfound dead in November near WestYellowstone. Early reports indicatedthe death may have been natural, butfederal law enforcement agents areinvestigating. The breeding femalehad died earlier this year, so the futureof the pack remains unknown.

WOLF ATTACK? That is thequestion asked by many readers

of a recent article in Range Magazineby Heather Smith. Featuring a claimby one of Idaho’s staunch wolf oppo-nents that he and his wife wereattacked by wolves in Idaho’s SalmonRiver country, the article relates howthe radio-collared wolf was shot 10feet from the man’s wife. The incidentis under investigation.

may have information regardingeither of the deaths should call theArizona Game and Fish OperationGame Thief at 1-800-352-0700.

PAY M E N T S F O R W O L FDAMAGE in Idaho, Montana

and Wyoming will be the subject of a University of Montana study. Theproject will evaluate the existing livestock-depredation compensationprogram in those states and howpeople from various realms view theprogram. ■

WOLF RECOVERY inthe northern Rocky

Mountains is well under way,and its progress through 2000has recently been detailed in agovernment report, available athttp://mountain-prairie.fws.gov/wolf/annualrpt00/.

WOLF GENETICS arebeing studied in Canada’s

Northwest Territories (NWT),and an information newsletterin lay terms is available atwww.nwtwildlife.rwed.gov.nt.ca/.The report covers the prelimi-nary findings of a study usinggenetics, conventional radio-tracking collars and satellitecollars on NWT wolves thatfollow caribou as they migratehundreds of miles betweenwinter range and summercalving grounds.

MI D W E S T W O L FSTEWARDS GROUP

will meet again in April 2002.This year’s meeting is sponsored bythe International Wolf Center and the University of Minnesota Duluth,Continuing Education, and will beheld in Two Harbors, Minnesota. Thegroup will be gathering to discusscurrent and future wolf issues in theMidwest.

THE U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFESERVICE has posted a reward

for up to $10,000 for informationleading to the apprehension of theindividual or individuals responsiblefor the recent shooting deaths of twoMexican gray wolves in Arizona.Individuals who were in the area or

Joha

nna

Goe

ring

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 25

26 S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 w w w . w o l f . o r g

Have you ever heard of (or smelled) a dog rollingaround in something really

smelly? That is called scent rolling.Some people think the wolf does this to hide its smell so that a preyanimal will not know it isapproaching, although scientists donot yet accept this explanation. Why

does the dog do it? The answer is thedog got the scent rolling instinct fromits ancestor, the gray wolf.

The dog is a domesticated graywolf. Domestication is selectivebreeding of animals toward behaviorcompatible with humans. The ances-tors of the dog are wild wolves thatwere selected to live with people.

Scientists think the domesticationprocess started at least 12,000 yearsago, about the same time thathumans changed from hunting andgathering food to farming. Whenwolves began living with people, theyhad to change some of their behaviorto fit in with the human family.Humans didn’t want wolves that weretoo aggressive or hurt humans. So thewolves had to act submissive—lethumans be in charge.

Wolves that lived with humans atescraps of human food instead ofhunting for deer or other large prey.So, unlike wild wolves, they did notneed strong jaws to eat raw meat andbone. After many generations, thejaws of the domesticated dog becameweaker. Today, a wolf’s jaw muscle ismore than twice as strong as a dog’sjaw muscle.

Over generations domesticatedwolves started to act and look likeyoung wolves even when they wereadults. Today, dogs have a shorter

Why Your Dog Rolls in Smelly Stuffb y A l e t h e i a D o n a h u e , I n t e r n a t i o n a l W o l f C e n t e r I n t e r n

Inte

rnat

iona

l Wol

f Cen

ter

Lynn

and

Don

na R

oger

s

The dog, such as the Australian Shepherd above, retained the scentrolling instinct from its ancestor, the gray wolf, shown to the right.

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:43 AM Page 26

I n t e r n a t i o n a l W o l f S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 27

muzzle, and some have droopy ears,which are characteristic features ofwolf pups. Dogs even act like youngwolves, by being submissive andfrequently wagging their tails. Somescientists say dogs are paedomorphic,which means they are stuck in ayouthful stage of life.

Some wolf characteristics stayedwith the dog—like the scent rollinginstinct. Dogs and wolves use thesame communication methods. Theyboth growl, bark and howl. Theyboth use body language, like tuckingtheir tail between their legs andputting their ears back. They bothuse their scent to communicate. Theyboth urinate to mark their territory.

Every animal has a set of instruc-tions, called genes, that tell the bodyof the animal how to grow. The genesof the gray wolf are almost exactlythe same as the genes of the dog. Thespecies gray wolf is divided intomany groups called subspecies. Somescientists think that the dog is aspecial subspecies of the gray wolfthat was domesticated. Biologically,that means the dog is a gray wolf! ■

Activities to try:■ Nobody knows for sure how the

first wolves came to live withpeople. Use the information youlearned here to make up your ownstory about the first dog.

■ Compare the size of this paw printto the paw of a dog you know.Which is bigger? Wolves use bigpaws to hunt. Dogs do not need tohunt, so their paws are not as big.

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:44 AM Page 27

28 S p r i n g 2 0 0 2 w w w . w o l f . o r g

In June 2001, I had an unusualexperience for a biologist. Ireceived a call from a producer in

Hollywood asking me to fly to LosAngeles to meet with him and hiswriting team. He was working on a new television show for CBS calledWolf Lake, and wanted me to talk to his crew about wolf biology and behavior. At first I hesitated and thought, “Is this guy for real?”Perhaps some friends were pullingmy leg and setting me up! I do workwith people who are good at thatkind of thing.

Accepting the invitation, I flew toLos Angeles the following week. Theproducer, five writers, and I spentone morning talking about wolfbiology and behavior. The show wasintended to be science fiction, but the writers wanted to depict wolves accurately. The show would includeshape-shifters who change fromhuman beings to wolves. Althoughthe writers seemed sympathetictoward wolf concerns, most hadlimited knowledge of wolf biology. Inabout three hours, I conveyed as

Wolf Lake and Wolf Mythsb y A d r i a n W y d e v e n

much information as I could aboutwolf biology that might be of value tothe show.

Afterwards I thought a lot aboutthis experience. My hope had beenthat although the show was sciencefiction, it might get viewers toappreciate and become concernedabout the conservation of wolves.We wolf conservationists stresseducation as essential to soundconservation of wolves, but toooften we are preaching to the choir.Perhaps through a science fictionshow we could encourage greaterconcern and appreciation of wolvesby people who normally don’t thinkmuch about wolves.

I missed the first two episodes ofWolf Lake but did see the third andfourth. The show appears to havelittle to do with wolves, and it washard to judge whether the little I sawof wolves was an accurate depiction.On the other hand, I did not seemuch that would promote negativeimages of wolves. I don’t thinkpeople will start believing that werewolves really exist.

But will the show create moremyths about wolves that conserva-tionists will need to address? Possible,but I think unlikely. As I readcomments from pro-wolf peopleabout Wolf Lake on the Internet, I saw several examples of myths weourselves are dispensing. Some of themyths coming from wolf enthusiastsinclude: wolves always mate for life,wolves live only in wilderness areas,loss of pets or livestock to wolvesoccurs only because the owners aredoing something wrong, wolvesalways are in total balance with theirenvironment, and wolves can do noharm. Perhaps we need to be lessconcerned about myths produced byshows like Wolf Lake than about someof the ones we create ourselves. ■

Adrian P. Wydeven is a mammal ecolo-gist with the Wisconsin Department ofNatural Resources, and has managedthe state wolf program since 1990.

Editor’s note: The program Wolf Lake is notcurrently being broadcast.

Cre

dit:

cbs

IntWolf.spring 02 1/22/02 7:44 AM Page 28

Shar

on H

alle

r

TeachersTake a weekend walk on the

wild side!

Check out www.wolf.org or call 800-ELY WOLF for more details. Cost of $295 includes food, resort, lodging, curriculum guide, and activity materials.

Enrich your classroom studies by participating in our

Wild Wolf Teacher Workshop March 8-10, 2002.

Curriculum section focuses on thebiological, sociological, political, and economic aspects of wolf management using the Center's new activity guide.

New Release from C. J. ConnerWolf Alliance Artist of the Year’95 and ’98

“ In the Shadows”18" X 24"

Limited Edition of 200 with 20 Artist Proofs

Giclee’ on Canvas

Regular Edition — $225.00

Artist Proof — $295.00

C.J. Conner StudioPO Box 102Chetek, Wisconsin 54728-0102

(715)353-2938www.cjconner.com

Cover.spring 02 1/22/02 8:26 AM Page 3

Intern

atio

nal W

olf

3300 Bass Lake Road, #202M

inneapolis, MN

55429-2518

NO

NPRO

FIT ORG

.

U.S. Postage

PAID

Permit #4894

Mpls., M

N

Rem

ember to

shop w

ww

.wolf.o

rg fo

r your fa

mily

and frien

ds!

Join Dr� L� David Mech� the world's foremost wolf biologist� Nancy Gibson� Emmyaward�winning naturalist� and Dean Cluff� Regional Wildlife Biologist of the NorthSlave Region� on a wildlife adventure into a remote area of pristine wilderness�

The trip is designed to offer International Wolf Center members an opportunity toexplore this unspoiled region� home to wolves� caribou� musk oxen� wolverine� barren�ground grizzly bears and a vast array of arctic birds�

The main objective of the trip will be to observe the dynamic relationship between themembers of a wolf pack and to learn about their prey in this wild landscape�*

Comments of past trip participants:

"Seeing the wolves� hiking� eating blueberries� Northern Lights� most of all – learning what being a field biologist is all about� Dave Mech was incrediblypatient� obviously knowledgeable� and (he) shared thatknowledge in an exceptional way… (I didn’t want to) have to come home!"

– Debbie ReynoldsInternational Wolf Center member