A Meta-Analysis of Community Action Projects - Volume oneFILE/communityactionprojects-vol1.pdf ·...

Transcript of A Meta-Analysis of Community Action Projects - Volume oneFILE/communityactionprojects-vol1.pdf ·...

A project funded by the Cross Departmental Contestable Fund through the Ministry of Health

A META-ANALYSIS OF COMMUNITY ACTION PROJECTS:

VOLUME I

Alison Greenaway Dr Sharon Milne Wendy Henwood Lanuola Asiasiga

Karen Witten

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki

Massey University PO Box 6137

Wellesley Street Auckland

Revised February 2004

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 2 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................................................................4

SECTION A: INTRODUCTION TO THE META-ANALYSIS....................................................7 1 Overview of the meta-analysis ........................................................................................7 2 Background .....................................................................................................................9 3 Research design ...........................................................................................................12 4 Description of projects involved.....................................................................................18

SECTION B: THE LESSONS LEARNT .................................................................................23 1 Lessons learnt: activation of projects ............................................................................24 2 Lessons learnt: consolidation of projects.......................................................................37 3 Lessons learnt: transition/completion ............................................................................48 4 Conclusion: cornerstones of community action.............................................................51 5 A framework for community action projects...................................................................58

APPENDICES Appendix 1: Policy and research background to the meta-analysis ....................................64 Appendix 2: Overview of the six evaluations included in the cases studies (four

projects were not evaluated) ...........................................................................66

REFERENCES .......................................................................................................................68

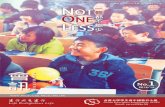

TABLE OF FIGURES Figure 1: Structure of the meta-analysis.................................................................................. 7 Figure 2: The 10 case studies ............................................................................................... 17 Figure 3: The TAIERI project in action................................................................................... 23 Figure 4: Key elements of community action......................................................................... 23 Figure 5: Students participating in the TAIERI Project .......................................................... 29 Figure 6: He Rangihou New Day Project of Opotiki Safer Communities Council .................. 31 Figure 7: Whaingaroa Environment Centre members in action............................................. 36 Figure 8: He Rangihou New Day Project of Opotiki Safer Communities Council .................. 58

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 3 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

With great respect we acknowledge the hard work of all the people who have been involved with the 10 projects included in this meta-analysis. We wish to honour them and learn from their commitment, vision and knowledge. Our thanks go out to all the people who participated in this research for their time and information. It is our hope that this report may be of some assistance to their work. We are grateful for the support, input and advice of Will Allen and colleagues at Landcare Research, our colleagues at SHORE, plus Cynthia Maling and Adrian Portis at the Ministry of Health. We would also like to acknowledge the involvement of the Ministries of Health, Pacific Island Affairs, and Social Development; Te Puni Kōkiri; and the Departments of Conservation, Internal Affairs, and Child, Youth and Families, as members of the Interdepartmental Reference Group involved in the setting up of the meta-analysis project. Finally, we acknowledge Claire White and Ray Prebble for their editing assistance.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 4 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This meta-analysis provides insights into the lessons learnt from 10 very different community action projects funded by a range of government agencies in New Zealand. The analysis has been used to inform a framework for community action projects, which identifies key developmental practices that will strengthen these and similar projects. The meta-analysis research project was undertaken by the Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Ropu Whariki at Massey University. It was funded by the Interdepartmental Research Pool (now the Cross Departmental Research Fund) with the Ministry of Health as the lead Agency. The project arose within the context of an increasing social policy focus on opportunities for cross sectoral collaboration through community action projects. This interest in community action revealed the need to provide evidence of the factors that enable or inhibit effective community action. Ten community action projects in New Zealand were studied to gain insights into the practices used, lessons learnt and key relationships that shaped the projects. The cases included three projects coordinated by Pacific organisations specifically for Pacific peoples and two projects coordinated by Maori organisations specifically for Maori. The range of cases studied had a geographical spread plus a mix of rural and urban projects. The projects had been funded by various government agencies including, the Ministries of Health, Education and Environment, the Departments of Internal Affairs, Child Youth and Family, the Community Employment Group, Work and Income and the Crime Prevention Unit. Other organisations funding some of the projects included the Alcohol Advisory Council, the Christchurch Police, Christchurch City Council, Waitakere District Health Board, NZ Landcare Trust, and the University of Otago. The case studies were produced from key informant interviews and document reviews. A grounded theory approach was used to create a meta level of analysis across the case studies. This analysis examined the barriers and enhancers to community action. From the meta-analysis a framework was developed to inform future community action projects. The meta-analysis revealed that while diversity is an inherent feature of projects working to create change through community-based decision-making, there are practices and perspectives common to them all. Fundamental to all 10 projects was the importance of building relationships that are transformative − that is, relationships between individuals and organisations that enable existing understandings and ways of working to be challenged and where required new ways trialled and adopted. Related to this point was the finding that projects were enhanced when the power dynamics influencing communities and stakeholders were acknowledged and addressed throughout the course of the project. Also evident across the 10 projects were notions of developmental processes and critical reflection that build knowledge and encourage participatory decision-making.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 5 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

The meta-analysis found that effective community action required: • skilled leadership • adequate resourcing • infrastructural development • committed strategic support from both government agencies and community

organisations • co-ordination • vision building • facilitation • advocacy • networking • mentoring • planning • critical reflection.

Projects benefited from the support of people with community development expertise and the skills to create the conditions for the above factors to occur. This expertise and skill could be held by people in a variety of roles including:

• community development advisors • fund contract managers • mentors from an umbrella organisation • project co-ordinators • evaluators • advisors from a fund holding organisation • trustees.

The community action projects developed knowledge and influenced practices when some form of reflective practice was incorporated in the project. Action reflection cycles were integrated into project planning in diverse ways, including:

• participatory research • formative evaluation • systematic reviews • informal review discussions • story telling.

In whatever form, practices adopted to reflect on the work being undertaken, the reasons why certain decisions were made and the gathering of information to inform future project decisions helped projects to achieve their objectives. The 10 projects each went through phases of activation, consolidation, and transition or completion. The activation phase saw the development of visions for the project based on identifying the issues and needs the project was planning to tackle and ideas for how best to do this. The consolidation phase involved identifying the skills and information required to make the desired changes, as well as continuing to build interest and participation in the project.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 6 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

The transition phase of projects was a challenge, with some projects ending and most converting to another organisational form. The meta-analysis culminates in the presentation of a framework for planning and reviewing the development of community action projects. This framework is based on the three principles that were found to enhance the projects:

• projects created change through transforming relationships between individuals, groups and organisations

• projects created change through developmental practices • projects built knowledge through practices of critical reflection.

Based on these principles, the framework presents practices for creating change through community action projects, plus critical reflection points and possible activities to assist their development. The framework is a reference tool for all stakeholders in a community project. It can be used to help individuals and organisations to plan projects together and to consistently undertake critical reflection as projects develop and reach a point of completion or transition.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 7 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

SECTION A: INTRODUCTION TO THE META-ANALYSIS

1 Overview of the meta-analysis

Purpose This report presents a meta-analysis of community action projects based on insights gained from 10 projects spanning the length of New Zealand. The meta-analysis synthesises barriers and enhancers to creating change in communities in order to inform a framework for community action projects. The framework presented at the end of this report is provided as a guide or tool for the planning and review of community action projects. The meta-analysis has been written for a diverse audience. We hope that this information will be useful to people working with community projects in a variety of roles. The specific aim is to help people whose task it is to co-ordinate community projects, evaluate projects, manage the funding for projects and/or create policy for funding them. The meta-analysis was funded in 2001 by the Ministry of Research, Science and Technology (MoRST) through the Interdepartmental Contestable Research Pool (now the Cross Departmental Contestable Fund), with the Ministry of Health as the lead agency. The research has been undertaken by a team of researchers working with SHORE (Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation) and Te Röpü Whäriki at Massey University.

Structure of the report

Activation of community action

Consolidation of community action

Transition of community action

Cornerstones of community action

Power analysis

Transforming relationships

Developmental roles

Developmental processes

Critical reflection/ knowledge buildling

Figure 1: Structure of the meta-analysis

The report is in two volumes. Volume I covers the background to the meta-analysis, introducing the concepts of collaboration, participation, relationship building and social change that are central to community action. The analysis is presented through a discussion of the lessons learnt during the phases of activation, consolidation, and transition or closure of community action projects.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 8 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

The case studies are presented in Volume II. They reveal a diverse range of community action experiences and provide the detail from which the analysis in Volume I was developed. Each case study discusses the context in which the project was developed, the practices (activities and processes) used in its development, the relationships that shaped it, and some of the lessons learnt throughout the project�s course. For the purposes of this research the generic terms of project co-ordinator, researcher and funding official have been used to represent the various positions involving co-ordination, evaluation/research and funding/agency liaison in the 10 projects. Reflections on these roles have been highlighted in vignettes throughout the sections in Volume I on lessons learnt. Factors that connect the three phases of the project development are presented as cornerstones of community action. These cornerstones inform the principles of community action on which the framework is based (see Figure 1 above). The framework presents features that are common to community action projects across government sectors, as well as reflection points and activities that may help projects as they develop.

The case studies The case studies in Volume II provide insights into practices used, lessons learnt and key relationships that shaped the 10 community action projects. A chart providing an overview of each project is provided in the Appendix to Volume II. These projects addressed very different issues and involved a range of approaches to change and structures for creating change. The terms used for various roles in the projects varied enormously, so for the purposes of this report we have used the generic terms in the box below to distinguish between the many players in the projects.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 9 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

Glossary of terms used Agency: a unit of central or local government (eg, a department or ministry)

Funder: the agency that provided the core or initial funding for the project

Fund-holding organisation: the organisation that administered the funding for the project, if not for the project itself

Umbrella organisation: an organisation that provided some form of oversight for the project

Project provider: the group or organisation that directly implemented the project

Stakeholders: individuals and organisations that have a stake in the project and have participated in its development

Formative evaluation: evaluation undertaken from the start of the project − this assists the formation of the project through strategic planning, identification of indicators, research and knowledge, and skills sharing

Process evaluation: evaluation that documents the process being used to develop the project in order to inform the development of the project and future projects

Impact evaluation: evaluation that assesses the direct impact the project has had within a short timeframe (eg, within five years)

Outcome evaluation: evaluation that assesses the wider outcomes created by the project within a longer timeframe (eg, after five years)

External evaluation: evaluation where the evaluator was contracted from an organisation not directly involved with managing the project (this includes evaluators from the funding organisation)

Internal evaluation: evaluation where the evaluator was contracted from an organisation directly involved with managing the project (eg, a project member, or the co-ordinator).

2 Background

Community action has been identified by various government agencies and social scientists in New Zealand and internationally as an important vehicle for creating sustainable social change.1 Central to these perspectives is the assertion that community-based projects encourage collaboration, multi-stakeholder participation and a focus on outcomes. Community action projects in New Zealand vary greatly in form and function. They are used as a means of tackling a variety of issues on different scales and with a range of groupings of people. Community action has the potential to create outcomes of common good across sectors and across oppositional interests in geographical locations. Whether this potential can be actualised is being debated in social policy and research fields, as well as within community organisations.

1 For examples of government funded approaches to community action in environmental management, see

http://www.landcareresearch.co.nz/research/social/; in social development the stronger communities action fund http://www.cyf.govt.nz/view.cfm?pid=195. For minimising alcohol-related harm, see http://www.alcohol.org.nz/resources/publications/Action_on_Alcohol/index.html. For international references, see Sankaran et al 2001, and Casswell et al 1999).

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 10 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

The meta-analysis of community action projects engages with this debate by examining the barriers and enhancers to community action in 10 projects funded by a number of government agencies. The following discussion presents meta-analysis as an important means for identifying and analysing practices common to community action projects that enhance the ability of communities to create sustainable social change.

What is a meta-analysis? The meta-analysis approach has been designed to generate insights about effective project practices and processes across multiple experiences and cases studies. By examining the dynamics that go beyond individual projects, we aim to inform the practice of community action by extrapolating from lessons learnt, and to contribute to the body of knowledge about community-based change in New Zealand. The meta-analysis approach used for this research differs from more typical meta-analyses, which concentrate on the quantitative combination of many studies on similar topics (Cochrane Collaboration 2003). We also differ from meta-analyses undertaken in the field of programme evaluation, where a meta-analyst gathers evaluations of similar programmes in an effort to gain the statistical power to see whether the interventions had an effect on participants (Posavac and Carey 1992, Light and Pillemer 1984, Lipsey and Wilson 2001). In our research the task has not been to evaluate the changes the projects have made or the processes they used, or their evaluations (Rogers 2000). This meta-analysis utilises research practices of induction and interpretation to build a store of knowledge for future project development, more effective project implementation, and enlightened policy-making. This form of meta-analysis meets the challenge described by Noblit and Hare (1988:7, cited in Patton 1990) of retaining the uniqueness and holism of personal accounts even as we synthesise them through an analysis of common themes.

What is community action? Community action is an approach to creating change on a scale that is local and accessible to the participants. There is usually a very specific focus (eg, improving river water quality, or school suspension rates), and actions are aimed at changing particular behaviours, experiences and/or practices through participation and education, involving a range of stakeholders. Community action projects or programmes promote problem-solving within the affected community, and ownership of the solutions. A key feature is developing the skills and analysis within the community so there can be fundamental and long-term change to problematic systems and structures (McCreanor et al 1998). This approach to social change creates activities that are responsive to the diverse needs of community sectors and to their changing circumstances (Moewaka Barnes 2000, Casswell and Stewart 1989). Practices used in community action projects enable the development of skills and knowledge that shape broader community development agendas. Community action enables community development through its focus on processes for creating change. The core principles of empowerment, equity, collaboration and consensus inform these processes.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 11 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

Why is community action important?

Community action builds social relations and community capacity Over the last two decades social science research and social policy has been giving increased attention to examining how social relations influence the wellbeing and development of societies (Coleman 1988, Putnam 1993, Kawachi et al 1997, Robinson 1997, Baum 1999, Fukuyama 1999, Labonte 1999, Pretty and Frank 2000). The term �social capital� is often used to describe the networks of relationships that facilitate changes within societies, from the level of individual projects to the level of communities and nation states. Community action is gaining increased attention due to its emphasis on building the relationships and networks required for making changes as well as for building the capacity of communities. Capacity building through community action develops and utilises the skills and knowledge of people who collectively resolve common problems (Goodman et al 1998; Casswell 2001; Chaskin et al 2001; Labonte and Laverack 2001 a&b). The notion of community capacity refers to the resources, skills, knowledge and infrastructure accessible to people for their collective development.

Community action enables greater participation in decision-making Like capacity building, participation in community action is both a means to an end and an end in itself. Research into participatory processes for decision-making and increased community participation in policy formation reveals the strengths that can be developed through social action focused on specific issues (Bracht and Tsouros 1990, Labonte 1996, Baum et al 1997, Casswell et al 1999, Saville-Smith 1999, David 2002).

Community action encourages collaboration across stakeholders Multi-stakeholder approaches are a way of ensuring the participation of key organisations and individuals who will be affected by, or benefit from, the initiative (Putnam 1993, Moewaka Barnes 2000). This approach aims to ensure that many perspectives are taken into account and planned for from the outset of a project. A key aspect of this approach is the creation of collaborative ways of working that often endure beyond the completion of a specific project. Collaboration of government and community organisations (now commonly referred to as vertical and horizontal linkages) maximises financial, knowledge and people resources, and minimises duplication. This perspective has produced a range of �joined up thinking� initiatives in both New Zealand and the UK (Chaskin et al 2001).

Community action incorporates a wider knowledge base into decision-making Community-based action and research can facilitate the building of knowledge about practices that lead to outcomes, and assist evidence-based project planning (Whyte 1991, Park et al 1993, Greenwood and Levin 1998, Casswell 2000, Cervin 2001, Reason and Bradbury 2001). Internationally and in New Zealand the social policy field is marked by strategies for building evidence-based decision-making. This term refers to the practice of policy development based on clear evidence of the issues, solutions that have worked in the past, and the implications of specific actions (Lynch et al 2000, Raphael 2000). Debates around evidence-based decision-making raise questions about whose evidence gets listened to and when. There are also challenges from the fact that evidence is constantly building and its interpretation is dependent on the context and research approaches taken (Moewaka Barnes 2000). Conway et al (2000b:339) suggest there is a range of benefits for community action projects where both the communities and researchers work together to share local and external skills and knowledge.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 12 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

Why a meta-analysis of community action projects? The role of community organisations in providing social welfare and creating social change has received significant political attention in New Zealand over the last decade. Recent social policy debates2 have arisen over questions of what constitutes effective community-based practice and government responsiveness to community needs. The following are some of the questions driving social policy debates that shape the context in which the meta-analysis research has been developed.

• How can the relationship between government and community/voluntary organisations be strengthened?

• How can the state sector�s social policy-making capacity be strengthened? • How can social science knowledge be built across government sectors? • How can social policy, research and practice be connected? • How can community outcomes at the local government level be measured? • What is best practice for government-funded community projects?

In summary, community action has been identified by various government agencies as a vehicle for creating sustainable changes within communities and in localised areas. In addition, community action has the potential to create outcomes that are of common good across sectors. It is therefore important to identify and analyse the practices that can be used in any community action project to enhance the ability of a community to create the desired changes.

3 Research design

The meta-analysis developed from discussions between evaluation researchers from the public health and environment sectors. The researchers were aware that similar approaches were being used to create community-based change in these sectors, and wanted to explore what the lessons learnt across all government sectors had in common. Parallels across projects were noted, including the barriers to communities engaging in project development, factors that contribute to their success, and the importance of building community infrastructure and capacity at a general level. It was thought that there was a great opportunity to learn from cross-sector experiences through analysing projects that had met with different levels of success. As noted, this discussion occurred in the context of growing debates about evidence-based decision-making and best practice for funding community projects. The Ministry of Health took up the researcher-initiated proposal and became the lead agency for a funding application to the Interdepartmental Contestable Research Pool, administered by the Ministry of Research Science and Technology (MoRST). The Ministry of Health then formed an interdepartmental reference group to oversee the project. In 2001 MoRST allocated funding for the meta-analysis of community action projects. The researchers� proposal submitted to the Ministry of Health was budgeted to involve mainstream and Mäori-specific projects and to develop a mainstream conceptual framework for community action research, with a discussion of ways in which the framework is consistent with or divergent from kaupapa Mäori approaches. In 2002 the reference group extended the project to include Pacific case studies.

2 For a more detailed description of these debates and references see Appendix I.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 13 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

At one stage in 2001 it was suggested that the reference group would develop a second, complementary application to the Interdepartmental Contestable Research Pool to seek funding to enable parallel frameworks to be developed for �by Mäori for Mäori� community action research, and for �by Pacific for Pacific� community action research. Unfortunately, this later initiative did not eventuate. The project was originally designed to review the evaluations of the community action research projects in order to identify the factors that had enabled or impeded each project to achieve its objectives. This design was based on the assumption that a number of projects had undergone formative-type evaluations such that their processes and activities were documented and the impact of these had been measured. This assumption was found to be incorrect, and after the initial scoping the research design was modified. Another key aspect of the original design of the meta-analysis was to gather information from three perspectives:

• the highly involved members of the community action research projects � the people who do the day-to-day work of the projects

• the people who were involved in evaluating the projects • the people who were involved in funding the projects.

We intended that representatives from each of these groups would come together to form co-ordination, evaluation and funding reference groups to guide the development of the research process.

Selection of the 10 projects The following criteria were used to select seven out of the 10 projects. The criteria are listed under two tiers. First-tier criteria were the essential characteristics in terms of meeting the project and contract objectives. The second-tier criteria guided the selection process to ensure a heterogeneous mix of case studies. The first-tier criteria were as follows:

• The project is a community action research project, community-based with a research/evaluation component.

• The formative or process evaluation is well documented. • Community representatives, the researchers and funder are available, are willing to

participate and are knowledgeable about the history of the project. • Of the 10 case studies, three are to be Mäori-specific and three are to be Pacific-

specific (and meet the other first-tier criteria). The second-tier criteria were as follows:

• The case studies span sectors (funders), population groups and issues. • The case studies represent urban/rural areas and are geographically spread. • Diverse models for community action research are represented (eg, both community-

initiated and government-agency-initiated, departmental evaluation and external evaluation, single and multiple funders, projects shaped by different political and socio-environmental contexts).

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 14 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

Initially we envisaged that case studies would only be considered for inclusion if they met the first-tier criteria. Selection beyond this point was to be focused on selecting a diverse group of adequately documented case studies. Taking into consideration the scarcity of formatively evaluated community projects and the even greater scarcity of �by Pacific for Pacific� community projects, the meta-analysis team developed selection criteria based on the project having incorporated some type of evaluation that documented its processes. This was with the exception of the three Pacific projects and one �by Mäori for Mäori� project. The �by Mäori for Mäori� project was selected on the basis of having other forms of documented reflection on its development. The selection of projects from across locations, communities, government sectors and time periods has resulted in the inclusion of 10 diverse examples of community action. This diversity is acknowledged and remains a central element of the analysis.

Shifting the focus from community action research to community action The initial scoping of suitable projects provided a better understanding of them and some familiarity with the documentation available. As a result, the design of the meta-analysis was further revised. The team decided to implement a more developmental approach to the research project rather than the more passive document analysis and workshop approach originally planned. The diversity of evaluation approaches by funding agencies and community projects meant that the project evaluations had little in common, and therefore did not provide a consistent source of information on the barriers and enhancers the projects had experienced. Also, very few of the projects had an opportunity to use the evaluation process to develop and build knowledge, so the terms �formative� or �process� evaluation could not be equated with research, as was assumed. In the absence of this form of evaluation research, we needed to explore alternative reflective practices for most of the projects. These issues shifted the focus of the meta-analysis away from community action research and towards community action projects. We recognised that it would be beneficial to emphasise change as the central focus of the research. In doing so, the researchers were more readily able to engage with and understand the labels the participants used, rather than pre-empting the identification of these components and thereby potentially missing critical processes and actions. This focus on change identified the primary research question driving the meta-analysis, which was: How is change facilitated through community action projects? As a result, reflective practices − how groups documented their actions and questions of how change occurred − became the focus of the research. A framework was designed out of this clarification of the research process to further develop the meta-analysis.

The framework for the meta-analysis of community action

Purpose of the research To develop a conceptual framework for community action projects, guidelines and milestones for monitoring their implementation.

Research objectives The objectives were to:

• explore the dynamics of action and reflection in 10 diverse community action projects • provide insights into the barriers and enhancers to change identified across the

10 projects

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 15 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

• develop a conceptual framework for community action • develop guidelines and milestones for monitoring their implementation.

The boundaries of the analysis were:

• not to undertake an evaluation of the projects • not to evaluate the available evaluations • not to assess the impacts or outcomes of the projects.

Key research questions • What processes and activities did the projects utilise to create change? • What were the barriers and enhancers to creating change? • How did the relationships between evaluators, funders and community groups create

change? • What were the reflective practices utilised in the 10 selected projects? • How did these reflective practices inform the actions taken in the course of the project?

A grounded theory approach This research is based on a multiple-methods, grounded theory approach. A grounded research perspective develops theory as part of the research process and as part of �a continuous interplay between analysis and the data� (Strauss and Corbin 1994:273). Grounded theory thus enables theory to be developed out of experiences, and tests this through both inductive and deductive processes. The development of methods as part of a grounded theory approach reflects an understanding of iterative cycles of analysis based on reflection and action that are central to community action and community development. The research was designed to include layers of checking, feedback and iterative development of the analysis.

Methods We discussed with evaluators, community group members and funding officials a range of issues that were important for the meta-analysis to address in order to identify the most effective way of approaching the research questions. These issues included:

• ensuring that within each project the relationship between all stakeholders − including the funders, evaluator and the project group − were examined in order to understand the wider context of each project

• understanding the impact of the processes and activities that have (or have not) led to change (it is important to explore the relationship that funding officials have within their organisations as well as those they have with the project workers)

• recognising that the research team was not separate from this information-gathering process and relationships, the research process reflected some of the best practice notions exemplified by the research participants and derived from the team�s wider research experience.

As was later confirmed by the data, relationships were a critical component in this meta-analysis, alongside activities and processes. We also identified that each project needed to be understood in its immediate context and history, and that these factors would need to be incorporated into the meta-analysis and design.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 16 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

After identifying possible projects, contact was initially made with people already in a co-ordination role. The research and what the project involved were discussed. Each project was sent an information pack with consent forms. All project sites were then visited to exchange information and access existing evaluation documentation and other relevant reports. Project members were also invited to contribute to the analysis and write-up of the final phase of the project. Once key project members had confirmed their participation in the meta-analysis, other key informants for the projects were identified and contacted for interviews. All informants were encouraged to provide feedback at various stages of the information gathering and analysis and were asked to check any project-specific information used in the final report.

Interviews and reference conversations Up to six people per project were interviewed. These people had either been directly involved as a member, evaluator or funding official attached to the project. In many cases the contract manager for the project had moved on, so it was not possible to interview many of the funding officials. To ensure the perspective of funding officials was captured, a range of officials who worked with community action projects (but were not directly associated with the selected projects) were interviewed. As noted, the meta-analysis was designed around the idea of active participation. We planned for the researchers to be in continuous contact (via reference group meetings and web site discussions) with the participants and reference group members, and for this conversation to shape the research as well as produce the findings. However, this design was based on the assumption that people would be interested in this level of participation. In reality the researchers found that participants wanted to engage with the meta-analysis on a variety of levels: some at the level of meta-analysis, but most at the level of the project�s or individual�s experiences of creating community-based change. These conversations were sporadic and generally directed by the needs of the researchers. Due to the diversity of evaluation approaches and the challenges of talking across sectors, professions, areas of interest and priorities, the research focus moved away from the idea of bringing people together for workshops. The research team realised that rather than having collective conversations with groups as part of workshops it would be more appropriate to have strategic conversations with people individually or in small groups. This would create strategic participation that reflected both people�s level of interest in the meta-analysis and what they expected to receive back from the research at a time that was right for the project and right for the participants. We also recognised that there are numerous multi-stakeholder research projects being undertaken at present, and a number of the participants commented on feeling over-researched.

Review of project documents Documents reviewed included the evaluation report for projects (where available), progress reports, mission statements, feedback forms, minutes and work plans. These documents were a means of finding out how the project members and the funders reflected on their work and processes. Information gained from these documents was examined alongside information gained from the interviews and discussions. This was essential to the grounded approach of the meta-analysis and enabled the data that had been gathered to be confirmed or challenged by data from a variety of other sources.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 17 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

Summary Data collected included:

• project-specific documents, including evaluation reports • input from the initial evaluators� workshop • interviews with key stakeholders • strategic conversations across all sectors and roles that were ongoing throughout the

research (some of these people were also involved in the analysis). All the data was collated, analysed and themed. This was part of the team process and utilised the SHORE researchers, who have specific and extensive experience in the development of community action research projects.

Moerewa Community Project1. Moerewa2. He Iwi Kotahi Tātou Trust3. ALAC, CEG4. n/a5. Community development

including social, cultural and economic

6. 1995�

Peaceful Waves/Matangi Malie

1. Auckland2. Group Special Education3. Ministry of Health, Public

Health Directorate4. n/a5. Non-violence

programmes6. 1995�

Whaingaroa CatchmentManagement Project

1. Raglan2. Whaingaroa Environment3. Ministry for the Environment4. Process/impact5. Public meetings, tours of the

catchment, catchment management plan, formation of the Whaingaroa Environment Centre

6. 1995�

Rough Cut YouthDevelopment Project

1. Westport/Buller region2. Buller REAP3. Department of Internal

Affairs and Work and Income NZ

4. Process/impact5. Film-making course

including life skills training

6. 1999�2003

Waitomo PapakaingaTracker Programme

1. Kaitaia2. Waitomo Papakainga

Development Society Inc3. CYF, CPU4. Process/impact5. Youth development �

social, education, cultural6. 1998�2000

Pasifika HealthcareGardening Project

1. Waitakere City2. Pasifika Healthcare3. Waitakere DHB,

Healthlink4. n/a5. Community garden

and back garden competitions

6. 1998�

He Rangihou New Day Project1. Opotiki2. Opotiki Safer Communities

Council3. Ministries of Education and

Health4. Formative and impact5. Drug education, health

promotion, capacity building, Māori focus initiatives, policy consultation, alliance building awareness raising

6. 1998�

Christchurch Youth Project1. Christchurch2. Christchurch City Council

and Christchurch Police3. As above4. Process/impact5. Youth worker project working

Monday�Thursday with young offenders and their caregivers, referred by Police Youth Aid; street youth work on Friday nights

6. 1997� PACIFICA Governanceand Management Project1. Nationwide2. PACIFICA3. CEG4. n/a5. Governance and

management training for members

6. 2000�

TAIERI1. Otago2. TAIERI Trust3. SMF, NZ Landcare Trust, University of Otago4. Process/impact5. Development and management of a

community-based catchment management project. Activities include workshops and education in schools and community.

6. 1999�

Key1. Location2. Provider3. Funder(s)4. Type of evaluation5. Activities6. Duration

Figure 2: The 10 case studies3

3 ALAC = Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand; CEG = Community Employment Group; CPU = Crime

Prevention Unit; CYF = Department of Child, Youth and Family; DHB = District Health Board; REAP = Rural Education Activities Programme.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 18 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

4 Description of projects involved

A brief description of the projects studied is provided here. Detailed case studies are provided in Volume II.

Waitomo Papakainga Tracker Programme: Kaitaia The Waitomo Papakainga Development Society is an incorporated society, formed by the Rawiri whänau and whanaunga in 1993. It was established for the specific purpose of meeting the needs of rangatahi. In 1998 the whänau obtained funding for the Waitomo Papakainga Tracker Programme. The Tracker Programme was one of many programmes the Society was involved with. Based on tikanga Mäori, whanaungatanga roles and responsibilities, and a whänau/hapü development approach, the initial Tracker Programme idea emerged from the whänau �just doing what they needed to do� to address the issues they could see in the young people around them. It was initiated as a kaitiaki structure focused on their whenua. The Tracker Programme evolved after many years of whänau working with rangatahi at risk or those with identified problems. The intensive live-in outdoor programme involved a group of mentors living and working with the young people for a three-week period with ongoing whänau support:

... just a whänau thing. We didn�t have contracts with any organisation, any agency to be funded for this kind of stuff, we were doing it because we wanted to help the kids. (Interview, project co-ordinator)

The underlying strategy behind the Tracker Programme was to give young people an experience different to their usual daily routines using the resources available to the whänau. The natural environment of an isolated whänau beach site with few amenities provided the setting to work with the young people and help them with their issues. It was quality time, 24 hours a day commitment, and the whänau regarded it as a �natural thing to do�.

Moerewa Community Project: Moerewa The town of Moerewa in Northland had a history and high profile of negative statistics that had become accepted, both locally and by wider society. Since 1995 the He Iwi Kotahi Tätou Trust has taken a lead in empowering the community to address some of the issues it faces. There have been several phases of development as the community strove to enrich and revitalise this small, predominantly Mäori, rural town. Funding was initially obtained from the Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand (ALAC) in 1998 to initiate a project to address the community�s drug and alcohol problems. The project was designed using a community development framework. The project team had lived and worked in the community and understood drugs and alcohol to be a symptom rather than a cause of the issues facing the town. They believed that change would only be effective if the broader historical issues could also be addressed. The project team initiated public meetings from which a plan emerged based around three goals:

• to initiate opportunities and activities to inspire the young people of the area • to investigate meaningful and motivational occupations • to create an environment that would foster change.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 19 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

The Trust began to market Moerewa as �Tuna Town� and purchased a block of local shops for businesses to be established. The events and initiatives started to help the people of Moerewa to feel good about themselves and their town and paved the way for a community-building and rejuvenation process. They built on the uniqueness of the town and demonstrated that the town and its people had an economic value. They also focused on helping to change the �spirit� of the community by reflecting on the strong cultural heritage of the area and promoting Moerewa as a place where Mäori were succeeding and could feel proud.

Pasifika Healthcare Gardening Project: Waitakere The Gardening Project started from concerns about poverty among Pacific communities and the impact poverty was having on their nutrition. In 1998 a pilot project was set up to introduce preschoolers to vegetables. Nurses and community health workers had found that children were not eating vegetables, and it was hoped that by involving children in gardening, planting, watching the vegetables grow, then harvesting and eating them, the children would become interested in growing vegetables and gardening. To encourage adult interest, a �backyard garden� competition was set up for families. The entry criteria were to grow five different vegetables and five different flowers. This competition has been running for the past two years and last year there were 98 entries. Over the past year a community garden has been run on land made available by the Waitemata District Health Board. The vegetables harvested are given to needy families, usually those with children, in the community.

Peaceful Waves / Matangi Malie: Auckland Peaceful Waves / Matangi Malie is part of the Eliminating Violence Programme run in schools for Group Special Education. Peaceful Waves was set up as an initiative of the Auckland Samoan and Tongan communities, who were responding to the issue of family violence within Pacific communities. The project started off working with parents and families in churches and then moved into schools. Recently they have been delivering the programme to Pacific providers as another initiative to reach a different audience. The programme explores anger management in a Pacific context.

Whaingaroa Catchment Management Project: Waikato The Whaingaroa Environment group (known to many as WE) came into existence in March 1997, through a catchment management project facilitated by Environment Waikato and Landcare Research. Environment Waikato had secured funds in 1996 from the Ministry for the Environment�s Sustainable Management Fund to undertake a community-based environmental management project in the Whaingaroa catchment. The aim of this project was to undertake consultation with stakeholders in the Whaingaroa catchment area in order to develop a catchment management plan. The WE group formed as a result of the public consultation process that was facilitated by Landcare Research. WE operated as a networking group that supported the dissemination of information and ideas across environmental groups in the region. They held public meetings to raise awareness and to facilitate agreement on a range of environmental issues.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 20 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

By 2002 the WE group had created an incorporated society and transformed itself to become the Whaingaroa Environment Centre. Environment Waikato had withdrawn from administering the funds for the group and the Whaingaroa Environment Centre had entered into a different funding contract (for environment centres) with the Ministry for the Environment.

He Rangihou New Day Project of Opotiki Safer Communities Council: Opotiki He Rangihou New Day Project is an innovative community action project, which takes a holistic approach to reducing drug-related harm to youth. The project is based in the Opotiki district, which has a high proportion of Mäori and unemployed people and a flourishing cannabis industry. Its target group is youth aged 10�25 years, particularly Mäori youth, and the adults who most influence them. A wide range of complementary strategies are used, most of them bicultural/bilingual or Mäori-focused. Activities involve whänau/families, grassroots community networks, schools and local organisations, as well as young people themselves. The project is under the umbrella of Opotiki Safer Communities Council and its sponsor, Opotiki District Council. It was set up in 1998 as part of Community Action on Youth and Drugs (CAYAD). This was a research initiative involving five other communities, which was co-ordinated and formatively evaluated by the Alcohol and Public Health Research Unit and Te Röpü Whäriki of the University of Auckland. CAYAD was funded by the Ministry of Education and had a primary focus on school/community activities. The He Rangihou New Day Project continued with Ministry of Health funding and adopted mainly community-based strategies.

Rough Cut Youth Development Project: Westport/ Buller region Until recently the Rough Cut Youth Development Project was funded by the Department of Internal Affairs as a response to concerns about the wellbeing of young people in the Buller area. Buller is one of New Zealand�s most geographically and socially disadvantaged areas. Educational resources, employment and transport are key issues. Depression, loss of hope, low self-esteem and lack of motivation are serious concerns for some young people. The Rough Cut Youth Development Project was developed as a response to these issues. Buller Rural Education Activities Programme (REAP) in Westport acts as an umbrella for the project. Based in Westport, the Rough Cut Youth Development Project uses the services of a variety of local and national film professionals to produce a 12-week film course every year for young people. These �Rough Cutters� have access to a considerable range of skills that are essential to the film industry, but, more importantly, they can explore issues that may be acting as a barrier to their life progress and achievement of wellbeing. The project targets young people aged between 16 and 25 years. To ensure a balance of skills and maturity, and to optimise group dynamics, there are also five places open to those over 25. The project does not overtly target those at risk but links with local agencies who refer potential candidates. Criteria include social disadvantage, low socioeconomic status, family adversity and dysfunction, mental health problems, drug and alcohol problems, and adverse and stressful life events. As a result of this project community networks have been strengthened. At the end of the course the wider community were included at the presentation of all the individual film projects.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 21 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

The project had limited three-year Youth Suicide Prevention Funding, and because it was unable to access continuous funding it has ended. However, other projects that arose out of the Rough Cut Youth Development Project are currently being developed, and alternative funding is currently being sought with the support of REAP.

Christchurch Youth Project: Christchurch The Christchurch Youth Project developed out of a need expressed by some young people for a service that would meet the needs of young people under stress, and address the public�s concern about the levels of offending and violence in the inner city. It is a partnership between Christchurch City Council and the Christchurch Police. The project aims to decrease violent and criminal activity involving young people throughout the city, make Christchurch a safer place, increase positive opportunities available to young people, and improve co-ordination between groups involved with youth at risk. The project is co-managed by the youth advocate of the Council and the youth aid co-ordinator for the Christchurch Police. The project also has a police youth liaison officer, who provides the day-to-day project co-ordination. The Council provides salaries for three full-time workers and the Police provide the co-ordinator. The project was restructured in 1998, resulting in management changes. It has been evaluated twice and a progress report was completed in 2002. Two Pacific youth workers will soon be appointed to a project that will share accommodation, supervision and common goals with the Council/Police project. A Pacific trust will employ them and a member of this trust will join the management team of the project.

TAIERI Trust River Catchment Project: Otago The TAIERI Trust River Catchment Project (TAIERI = Taieri Alliance for Information Exchange and River Improvement) developed as part of a health and ecology PhD research project. The research process used community-oriented participatory action research methods to facilitate the development of a multi-stakeholder project to address both environmental and related community health issues facing the Taieri Catchment. By 2001 the PhD research project (titled the Taieri Catchment and Community Health Project) had created a partnership between the University of Otago and Taieri community members, which led to the formation of the TAIERI Trust and Project. Funding from the Sustainable Management Fund was accessed from the Ministry for the Environment for three years, due for completion on 30 June 2004. The TAIERI Trust has five trustees: four represent different geographic areas of the catchment and one represents the university. There is also a wider management group involving other community members, Fish and Game and the University of Otago. The project is distinctive in its initial use of community-oriented participatory action research methods. It is an example of a multi-stakeholder project that builds understanding across both scientific and social areas. Current activities include the development of a web page, a video resource for children to be used in schools, stream restoration activities, establishing community stream-care groups, organising workshops to address current environmental issues, ongoing development of the relationships between stakeholders, and the regular publication of a newsletter.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 22 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

PACIFICA Governance and Management Project: nationwide PACIFICA is a national Pacific women�s organisation set up in 1976 to advocate for Pacific women at a political level. They have branches throughout New Zealand and each branch runs its own projects. During 2001/02 PACIFICA received Community Employment Group funding to run governance and management training for its members so that women could be up-skilled to deliver services outside the organisation. It also allowed PACIFICA to review its constitution. This project has led to a new project, Mentoring for Leadership, which will support young women into leadership roles.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 23 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

SECTION B: THE LESSONS LEARNT

Figure 3: The TAIERI project in action

While the 10 projects studied were highly diverse, each went through phases of activation, consolidation, and transition or completion. The activation of the projects saw the development of visions for the project, based on identifying the issues the project was planning to tackle and ideas for how to do this. The consolidation phase involved identifying the skills and information required to make the desired changes, as well as continuing to build interest and participation in the project. The transition of projects was a challenge, with some projects ending and most changing to another organisational form. There were a number of common features across the 10 projects, which interwove through each phase of the projects. These are illustrated by the box on the right in Figure 4 below.

Activation of community action

Consolidation of community action

Transition of community action

Cornerstones of community action

Power analysis

Transforming relationships

Developmental roles

Developmental processes

Critical reflection/ knowledge buildling

Figure 4: Key elements of community action

We have called these �cornerstones� of community action. These cornerstones informed the project�s approaches, processes and activities, and they were integral to the range of barriers and enhancers each project experienced. As illustrated by the four circling arrows, the movement of a project from one phase to another was not distinct for most of the projects. Project participants moved between phases as information was gained, skills developed and membership changed, and as a result of reflecting on the progress of the project. The large arrow from the transition phase back up to activation indicates that while the specific project may have ended, the members of the project typically went on to work on other community-based projects or transformed the initial project into another form (eg, a service or agency portfolio). Consequently skills, relationships and knowledge were transferred, developing the capacity of individuals and their communities.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 24 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

1 Lessons learnt: activation of projects

A co-ordination perspective We believe strongly that without managing relationships we can�t manage at all. We have a good relationship with the funder, not like a phone or email relationship but a one-to-one, face-to-face relationship. We have a very good relationship with them based on the understanding that we need each other for this to work.

(Interview � project co-ordinator)

A funding perspective Communities bring huge experience, huge resources, and they bring knowledge from the community level. I see the role of agency staff is to bring the evidence base. The process of engaging the community is bringing these two strengths together. Then there will be interchange, such that both knowledge bases can intercept and visible changes are created from that process ... I think that as funders we can get a little bit divorced from the reality of what it is like trying to achieve something on the ground with real live people. It is important to be willing to apologise and work through these things. It�s like moving with your heart and your head.

(Interview � funding official)

A research perspective There was a lot of good will involved and I think it helped enormously to work with community organisations with whom we had existing (some tenuous) relationships. There needed to be a high level of trust and co-operation involved to move things as far and fast as we did. It also helped a great deal that the communities we worked with had already identified alcohol and drug issues as big in their areas so there was a real state of community readiness (even if there was some reluctance and reticence apparent in some parts of the community). It helped to have already done an extensive and relevant literature review and scoping exercise for the Ministry of Health, if we had to start from scratch it would have been an even more labour intensive exercise.

(Interview � evaluator)

Introduction The activation phase significantly influenced the future development of the 10 projects. This phase was based on relationship building and the development of a project vision, which was based on the identification of issues and strategies. The level of participation in the activation phase and the extent to which all the core stakeholders took ownership of the project varied across the projects, reflecting the relationships that had been built and the practices used to activate the project. Activities that assisted this phase were visioning sessions, the collection of data to form an evidence base about the issues being addressed (eg, needs assessments), plus a range of events that aided relationship building and raised the profile of the project (eg, tours of the catchment).

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 25 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

Identifying the need for a project The practice of matching community action projects to funding varied across the projects. There was whole continuum of experiences, with historical and political factors shaping these experiences. Most projects were the result of money being reallocated to new policy directives (eg, integrated catchment management, reduction of drug-related school suspensions, youth suicide prevention, kaupapa Mäori alcohol harm reduction). For the majority of projects the initial idea came from interested people within the community. When government agencies began seeking out localities in which to fund projects, these communities were poised for action. For example, in Moerewa community people were already working voluntarily to address local needs long before being approached by ALAC. A minority of projects arose from community groups approaching potential funding agencies directly. Each of the Mäori projects in the study grew from a need in the community and took a firm tino rangatiratanga stance. They determined their own issues and developed their own solutions and were accountable to the people in their community. Once issues had been raised, the community realised there was little infrastructure or capacity to deal with them. It was decided that the projects would deal with core issues and causes in a holistic way, rather than presenting issues or symptoms in isolation. Each of the Pacific projects addressed an issue that had arisen within Pacific communities, such as nutrition, family violence, and the role of governance and management in Pacific organisations.

Matching funding to projects Well, you�re best to get the right provider in the first place, have a very clear, simple process, provide the funding, and then keep out of it, unless you�re required for fire fighting, or particular issues. (Interview − funding official)

This statement represents a funding perspective that helps to build a supportive funding relationship with the key people and organisations involved in effective development. In this situation the funding official will have a good knowledge of the people working in the field and their track record of community projects. Trusting this experience and continuing the relationship are important, although problems with this stance are that newcomers to community action can be overlooked because they do not have the experience. There is a risk that certain parts of the community will be prioritised or have access to projects and not others. There is also a danger that well-established organisations may become set in their ways and not take on new challenges and information. They may continue repeating the same mistakes. Mäori providers noted that they are sometimes disadvantaged by agencies who choose to stereotype Mäori organisations just because there have been instances where there has been a lack of credibility in the past.

You�ve got policy and you�ve got appropriation. We ask projects we work with �What do you guys really want to achieve?� Because then we can discuss, �can we deliver that, honestly can we deliver that, is that something we should be in, or are we just seeking the money? Would it be better for us to go and talk to a couple of other groups in town here and say hey look, you�re better off doing this, not us, because it�s not really us�. A lot of organisations in the voluntary sector don�t have that questioning. I think we�re developing a culture now of clarity. (Interview � co-ordinator of umbrella organisation)

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 26 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

This statement indicates the important role an umbrella organisation can play in linking funding to appropriate community groups for projects that fit their philosophy and capacity. In the case of the Rough Cut Youth Development Project, the umbrella organisation was able to facilitate the process of matching funding to the community group. This role can be further enhanced if the umbrella organisation is able to encourage two or more groups to come together to work collaboratively on the project, and to support the development of these relationships and the infrastructural capacity that would be required. For some projects, just working out who was the right agency to approach for funding presented many difficulties. The different responses received from various parts of an organisation also presented frequent barriers to communication:

I did ask them [a government agency] if they could put something together for us to work with the preschools and they promised us that and they were going to come and meet us here and then they did not turn up. (Interview � project co-ordinator)

Building project relationships I think that the relationship between funders and organisations being funded should very much be a partnership. Partnership means several things for me. We say that we want to be really responsive to communities, and hear what communities need and what they think the solutions are. But for me partnership also means accountability and transparency around the way the funding was used. I know I don�t want to be part of a partnership that�s not like that. Face to face contact is also indispensable and that�s why I do get out and visit projects; it�s necessary. It applies with my relationships with the advisors; we all need to have confidence in each other and understand what our different agendas are. I find that that works really well. (Interview � funding official)

For all 10 projects the transformation of relationships was a central element. A critical point was reached across all the projects when relationships broke down or needed attention. For some of the projects, relationship building across stakeholders was planned for as an objective and was seen as essential for sustaining the project. In these instances activities were planned that would create tangible outputs as well as opportunities for people to learn from each other and find ways of communicating their concerns and knowledge. One example is where a project undertook a tour of the area they were working in and invited trust members, agency representatives, community members and funding representatives to join them to experience the issues first hand. The projects based on Mäori approaches placed greater emphasis on relationships and the need to accommodate their diverse realities. While focused on a specific purpose, the numerous discussion points and diversions along the way were just as important as the intended outcomes. Building Treaty-based relationships was a significant challenge for the Tracker Programme, the Moerewa and TAIERI projects, He Rangihou New Day Project, and the Whaingaroa Catchment Management Project. In the Whaingaroa Catchment Management Project the process of consulting with mana whenua and tängata whenua had resulted in some grievance issues. A central element of the He Rangihou New Day Project was the building of a bicultural partnership between the co-ordinators and the development of a project that was accessible to all those who had input into it.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 27 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

Funders, co-ordinators and evaluators facilitate relationship building For most of the projects, relationship building involved the co-ordinator and key project members building knowledge of, and familiarity with, people and organisations in the sector and the geographical area of the project. In some cases this was enhanced by the support of an umbrella organisation, through support from an advisor from the funding organisation, or by the researcher or evaluator. The facilitation of relationship building was identified as one aspect of the funding role that could be developed further. Because funding contract managers deal with a number of projects, they can assist by making introductions between projects to enhance opportunities for networking. The creation of networking opportunities by the funding agency or evaluators was found to be an important way of enabling learning across projects and for breaking down the isolation co-ordinators felt. As part of a wider research project, the He Rangihou New Day Project found there was funding available to enable the projects to get together on a number of occasions. Recent initiatives to bring integrated catchment management projects together were also being received by project members as a much desired opportunity to learn from other community projects (New Zealand Landcare Trust 2003). Projects were enhanced by collegial relationships with other community-based organisations or projects working in a similar field. These relationships led to information sharing as well as possibilities for peer review. A frequent dilemma for project co-ordinators is how much time to spend networking and how much time to �get on with the tasks at hand�. Finding ways of balancing day-to-day tasks with the need to maintain relationships was an important lesson.

Project relationships with evaluators The relationship project members had with the evaluators varied, reflecting the style and aim of the evaluation. In most cases the evaluator�s role was external to the project and was not drawn on as a resource for relationship building across stakeholders. Where participatory evaluation processes were utilised, project relationships were strengthened. It was evident that whanaungatanga links were critical to the relationships forming the Mäori-specific projects. The projects were enhanced when these existing networks of relationships were acknowledged as legitimate communication tools that provide meaningful social interaction at both a formal and an informal level. It is clear from the Mäori-specific as well as the other projects that it is important to identify who needs to be communicated with and what the representation and mandate issues are. For Mäori, the process of engagement in a shared investment is by way of a team approach. It must be interactive and �kanohi ki te kanohi� (face to face). Such protocols provide a process to clarify the proposed roles, responsibilities and expectations between the agency and funder at the outset, foster closer links, and enhance relationships. It also appeared to be useful if common understandings about the tikanga basis of the project and strong relationships were forged prior to entering into the contractual arrangement. If the vision and control were to be with the community, then local values and evidence needed to be drawn on. The word �partnership�, although commonly used, has a range of meanings, understandings and practices and is generally not modelled well. It is clear that agencies need to acknowledge the power inequalities that may exist in �partnerships� and demonstrate true relationship building and active support so that development can be enhanced. The notion of partnership requires negotiating roles and responsibilities at the outset, as well as a commitment to regular and ongoing communication.

Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation and Te Röpü Whäriki 28 Te Rünanga, Wänanga, Hauora me te Paekaka

Project relationships with funders ... sometimes that relationship can involve frequent visits and quite a hands on involvement; maybe the advisor sits in on all board meetings and participates actively. In other cases the worker and the agency are strong and skilled enough that they don�t really need that and so the advisor takes on more of a monitoring function but the monitoring function is certainly half of the role in all cases at least, making sure the project is delivering appropriately objectives that we have funded for. (Interview − funding official)

The relationship between funding agencies and community organisations was recognised as crucial in supporting the community action project. However, all projects other than the Pacific projects acknowledged difficulties in this relationship and called for greater emphasis to be placed on establishing a good relationship between funding agencies and community organisations that would enable each to work alongside the other for the benefit of the community.

The philosophy we have as a funding team ... is focused on developing and maintaining functional working relationships. So it is relationship based. It is not really about developing clear frameworks or indicators or guidelines, that can be a bit removed from the reality of community processes ... Our key role is to get the resource to where it can best make the difference. (Interview � funding official)