94750 Faure Edition Liner Notes Sung Text Download · 94750 Fauré Edition 2 applause went over to...

Transcript of 94750 Faure Edition Liner Notes Sung Text Download · 94750 Fauré Edition 2 applause went over to...

94750 Fauré Edition 1

FAURÉ EDITION Liner notes and sung texts

Liner notes

ORCHESTRAL WORKS The 'Dolly' of Fauré's suite was Hélène, the daughter of Emma Bardac, to whom Fauré was emotionally attached some years before her marriage to Debussy. The six‐movement suite has an appropriate tenderness that has always ensured its popularity. It was originally written for piano between 1893 and 1897; the orchestral score was made by Henri Rabaud c.1906. The arrangement of Masques et Bergamasques, on the other hand, was done primarily by Fauré himself. This is a suite of four pieces taken from a one‐act Iyrical divertissement, first staged in 1919; the orchestral suite dates from the same year. Fauré's score for Pelléas et Mélisande was composed as incidental music for the Maeterlinck play and was first heard in that form when the play was given (in an English translation) at the Prince of Wales Theatre in London in 1898. This time the original orchestration had been done by Fauré's talented pupil Charles Koechlin, but for the suite derived from that score Fauré reorchestrated certain movements. PIANO QUINTETS Both of Gabriel Fauré’s Piano Quintets (1906 and 1921) are mature masterpieces, although written fifteen years apart. They are hardly known, far less even than his two Piano Quartets Op.5 and Op.45 (1879 and 1886). The first quintet resulted directly from his experience with the second quartet: 'After Fauré in 1891 had made sketches for the work, which he imagined as a third quartet, he somehow was overwhelmed by his own music. This fact induced him in 1905 to give the new work the enlarged form of a quintet’. From 1891 to 1905 Fauré lay aside the Allegro and the Andante, as they did not satisfy him. The completed Piano Quintet in D minor Op.89 was first performed in March 1906 in Brussels, and played again two months later in Paris. The violinist Ysaÿe, to whom the work was dedicated, was deeply moved, calling it 'absolute music in the purest sense of the word'. Trying to describe the character of the work one could agree with the following statement: 'In spite of the serious atmosphere of the initial Allegro and the entrancement of the Adagio the whole work breathes serene clarity, untroubled freshness and infinite radiating abundance.' Nobody but Fauré himself had any doubts about the work, and his doubts were typical of the composer's difficult and somewhat tragic personality and fate, which manifests itself in a progressive hearing defect ‐ comparable to Beethoven in his late deafness or to Smetana, who, similar to Fauré, suffered terrible disharmonies in his ear. Thus, after a most successful performance of his first quintet in Paris, he was overwhelmed by an obviously un motivated anxiety. He was tormented by the lacking of a Scherzo as well as by the allusion of his Finale to Beethoven's 'Ode to Joy', which although intended, suddenly seemed to be too obvious. For it was typical of Faure to be afraid 'of using a hermetical language, as he was always tortured by the thought of not being understood: 'I feel in the bottom of my heart that what I really want is not accessible to everybody.' This statement is essential for the understanding of Fauré's later works. Its full meaning, however, can be realized only if one knows that it was made at the artist's zenith regarding his career: when Fauré wrote his first quintet, he was appointed director of the Paris Conservatoire, in spite of the opposition of the academic faculty. Fauré's appointment was revolutionary, as was the fact that during his administration he effected an enormous change within music education, thus creating a new

spiritual home for the young generation of French composers, whom he inspired tremendously. All this must be rated as something extraordinary, because Fauré until then had chosen an unusually quiet way of life, being simple church musician, not showing any special ambitions, cautious and reserved also with regard to his compositional work. In fact, even today he is difficult to place. No comparison could help to classify his work. His style is guided by a special kind of aesthetics, which one might call unrealistic. His musical thinking is dominated by one great flow, one total process; he does not stick to any rules, he just follows his inspiration. Fauré is never concrete, neither in writing songs, his first field of composition, nor in liturgical works, not even in symphonic and operatic works. His approach to form was always vague: in the very beginning, when in the domain of song he developed a new romance style of madrigalian freedom, or later, when he freed himself more and more from stylistic rules, finding a 'harmonic flow', whereupon he was accused of losing tonality. According to his pupil Koechlin, tonality to Fauré was always connected with a 'legitimate, expressive and musical cause'. The attempt of classifying Fauré as a representative of impressionism or one of its forerunners had to be dropped as unsuccessful due to his musical diction and his historical importance. Only the comparison with Debussy's different kind of aesthetics might eludicate Fauré's position: yet, whereas Debussy's language is dictated by concrete realities, in unconcealed clearness, and can be analysed back even to non‐musical roots, Fauré's is wrapped in ideas. Fauré never translates real pictures into music. His planning is 'from the start purely musical', as Bernard says, 'the only composer after Mozart to have found purely musical accents'. Fauré's second Piano Quintet, with all its peculiarity, does not in the least express either sorrow or distress, its composer being far from illustrating private thoughts by means of music. Fauré specialists have rated this second piano quintet in C minor as the 'summum opus' of his chamber music. It is astonishing to see how his intellectual process persuades by means of precise and dense musical consequence. Nevertheless, and in spite of its literally unreal beauty, this work does confirm some traits of that hermetical character which Fauré was trying to avoid from the beginning. His musical language takes on quite unreal and esoteric traits, apparently in contrast to Debussy's style. Again, and in spite of the overwhelming success of the quintet's first performance in Paris in 1921, Fauré was aware of this fact. He had arrived at the end of his term as director of the Conservatoire; he was now 76 years old and still convinced of the insufficiency of his music. At any rate, the following report of the first performance of the work, which was dedicated to Paul Dukas, makes us believe so: As the quintet was played for the first time in the old hall of the Conservatoire, performed by artists who were carried away with incredible enthusiasm, the audience was thrilled right from the beginning. We had expected a beautiful work, but not one as beautiful as this. We knew that Gabriel Fauré's music was significant, yet we had not realized that it had reached such heights without being noticed by the world. The more we heard of the work, the greater became the enthusiasm, an enthusiasm, however, that seemed combined with remorse, because one might have misjudged the old man who held such a gift in his hands. With the last chord everybody rose from his seal. Waves of

94750 Fauré Edition 2

applause went over to the reviewers' box, where Gabriel Fauré ‐ who, by the way, had heard nothing – stayed hidden. Quite alone he advanced as far as to the dress circle, warding off the applause. He looked at this hall, where Berlioz and Liszt, Chopin and Wagner had lived exciting moments, and he looked at the crowd, which was seized by the power of his music. He was very frail and thin, seeming to stagger under the weight of his heavy fur coat. He looked extremely pale. Back home again, he sat on his bed before going to sleep and said to us: ' Of course, such an evening is a joy. The exasperating thing about it is that afterwards you have to keep up with your own standard ‐ you have to keep us with yourself ‐ and you must try to do even better'. PIANO QUARTETS The Piano Quartet in C Minor, Op 15, is undoubtedly Fauré's best‐known work of chamber music, still popular today and frequently performed. It is in four movements, quite classical in form and procedure, but it is characteristic of the composer's masterly craftsmanship that the romantically passionate thematic material fits as naturally the classic mould as does Haydn's and that the imitations and counterpoint never become scholastic. They are carried out with the greatest ease, reminding the listener of two similar masters of ease and naturalness in counterpoint: Mendelssohn and Dohnányi. The first movement starts right with the main theme ‐ Fauré never resorted to an introduction ‐ announced by the strings, treated as a choir against the piano. He recognized and accepted the basic difference in sound and character between the piano and stringed instruments, and never tried to make the piano sing long, sustained melodies. It was not necessary. Opposing arpeggios, chords, broken chords, and runs to the singing of a single stringed instrument or of a choir of these and giving them and the piano equal roles in a rich contrapuntal texture offered more than enough opportunity to achieve variety. It is fascinating to see how concise the sonata form of this Allegro molto moderato movement is, while the texture incorporates all the luxuriant musical vegetation of the late romantic era. There is as much tumult and passion in the areas ruled by the first theme as one would expect from C minor, whether the composition is by Mozart, Beethoven, or Brahms. Though a surprising series of modulations ‐ enharmonic and other ‐ we reach the relative major key of E‐flat, and the lyrical second theme. After a coda in which the first theme reappears in the same key, there follows an ingenious and interesting development section leading to the recapitulation, in which the themes appear in their classically predetermined keys, and the movement ends ‐ the passion being exhausted ‐ in a pianissimo in which only the pulse of the syncopated chords of the outset remains alive. The second movement is a Scherzo, Allegro vivo in 6/8. After the pace has been set by pizzicato chords of the strings, the piano brings a twisting, twirling, dancy melody, somewhat like a forlane, in which young people, possessed and impelled by the driving force of their sinuous bodies, twist and turn, oblivious to everything but rhythm. One can almost hear their feverish breathing. The movement is in E‐flat and the six‐measure pizzicato preparation brings a quasi ostinato of I/VI/IV/I modified subsequently in fascinating sequences of chords. The meter changes back and forth between 6/8 and 2/4, adding the sensation of panting to the rapid movement of the rhythm. This movement is not classically concise any longer, although very precisely classical in form. Like Beethoven's scherzos, it approaches a rondo in its expansion. It has a Trio with a lovely and sweet melody sung by the muted strings, after a preparation of the piano this time, now in B‐flat, through another quasi ostinato of I/V/I‐V. After the enchanting Trio the Scherzo is recapitulated.

The Adagio returns to C minor. It is a three‐part song in which the strings are now treated not as a choir but as individuals, entering in imitation of a prayer‐like short melody over the rich chords of the piano, cadencing frequently. This prepares for the Allegro molto last movement that tears along at a furious pace that nothing can stop. This movement is really in sonata form, but no longer classical. The first subject is merely a motif, and a second rhythmic one is later combined with it, achieving what Fauré's pupil, Florent Schmitt, described as a perpetual renewal. The wonderfully singing second theme is yearning and full of lyrical passion. Most astonishing is the development section that takes these themes through all possible keys, mostly without modulation. A strong and masculine coda brings the movement to a fiery ending. The Piano Quartet in G Minor, Op.45, was composed in 1886. It is also in four movements, and as in the previous work, the Scherzo appears after the first movement. But, while Fauré's manner of writing is immediately recognizable in the way he handles the piano and the strings, there are notable differences between the two works. The second quartet leaves the classical mold behind, both in form and harmony. These are much bolder, the classical outlines blurred, and the first movement changes in the course of recapitulation and ends in major, a procedure we shall see repeated in subsequent works. The movement again has three distinct themes, but they have more character and originality. The first especially has an imperious sweep that shows the development of the composer's individuality. The Allegro molto moderato starts, as do the last two movements of the first quartet, with the piano "setting the key", an idiosyncrasy probably retained from song composition. Then the powerful rhetoric of the string body asserts itself, as does the first theme as well, hardly permitting the following subjects to have their say. Fauré again gives proof of his inexhaustible harmonic fantasy and goes so far ‐ as indicated above ‐ as to change the mode, thereby attempting to change the imperious character of the energetic first theme. It is as fascinating to watch this manipulation as it is to watch his metric manipulations in the next movement (Scherzo), Allegro molto. The meter here from 5/8 to 2/4 to ‐, without batting an eyelash ‐ that is, without having less than six to a measure. Thus we have sometimes a half note, sometimes a dotted half note, two quarters, or two dotted quarters between barlines, ritmo di due and di tre battute. This is real Scherzo, a play with notes, in which a widely arched melody ‐ rhythmic transformation of the main theme of the first movement ‐ is also fitted to the perpetuum mobile of the six eights. In the G major ending of the first movement surprised us, we are no less surprised by the Scherzo being in G major, the Adagio non troppo in E‐flat major. But this is a minor point compared to the transcendental beauty of its mood and its deeply moving melody. Throughout the first movement there is in the piano part something like the pealing of bells, and above it a fervent, ever‐renewed phrase, evocative of on Angelus. In French music, where words, a program, are never far below the surface, we have no compunction in assuming that the composer had just that in mind. Intoned at first by the viola, and accompanied by the "bells," the is soon taken over by the other instruments, and then confronted by another, related chant ill middle section. This movement is one of Fauré's most moving compositions. The last movement, Allegro molto, returns to G minor, but it again turns to G major, in which key it ends. It is impetuous music, and Fauré is again taking liberties with its meter, alternating runs in triplets with due battute, two eights against three, and cross‐accents. Similarly in the harmony, where we find an endless variety of changing keys and unexpected spicy discords ‐ an evanescent harmony with a strange personal way of progressing. This is music for a cultivated and civilized minority, as Eric Blom said.

94750 Fauré Edition 3

LA BONNE CHANSON OP.61 | PIANO TRIO IN D MINOR OP.120 Piano pieces, chamber music and songs ‐ all forms involving the piano, his own preferred instrument ‐ make up the major portion of Gabriel Fauré' s output as a composer. In each category the best hold their own among the greatest. This certainly applies to La Bonne Chanson. Fauré was not invariably fastidious in his choice of literary collaborator, but in Paul Verlaine he met his equal, so that in La Bonne Chanson, Op.61, composed in 1892‐4, as in the immediately preceding Cing Melodies 'de Venise' , Op.58, composed in 1891, words and music unite in perfect harmony. Verlaine wrote the poems of his 'good' Song when, during the Winter of 1869 and the Spring of 1870, he was courting Mathilde Mauté, the half sister of his musician friend Charles de Sivry, and the daughter of the Madame Mauté de Fleurville, the Chopin pupil who taught the young Debussy how to play the piano well enough for him to be admired to the Paris Conservatoire at an unusually early age. Verlaine's marriage was short‐lived, but the happy adoration of La Bonne Chanson contains not a clue to the ambivalent tendencies which, with the arrival of the young Arthur Rimbaud, wrecked any physical attachment he may have felt for his child‐wife – she was sixteen when they married: he, twenty five. Of the twenty one poems published as La Bonne Chanson, Fauré chose nine, they are, in order, Nos. 8, 4 (the first, fifth and last of its seven verses), 6, 20, 15, 5, 19, 17 (the second, third and last of six verses), and 21 (omitting the second of its five verses). If the sentiments of the poems are those of a young lover towards his fiancée, the songs ‐ like most of Fauré's ‐ were conceived for a female voice. Although first (In Paris, on April 25, 1894) by Maurice Bagés. La Bonne Chanson is dedicated to Madame Sigismond Bardac, a soprano frequently accompanied by the composer himself, the mother of the Dolly for whose successive birthdays Fauré wrote the movements of his well‐known suite of piano duets pieces, and the lady who later became the second Madame Claude Debussy. In 1898, Fauré was persuaded to score an arrangement of the piano accompaniment for string quintet and piano. This was successfully performed, with Bagés as soloist, at a soirée given at the London home of Fauré's friend Frank Schuster on April 1. The following day, in a letter to his wife, Fauré recorded: ‘Yet, for my part, I still find this accompaniment redundant, and prefer the simple piano accompaniment.’ He added, however: ‘But its effect was great: Schuster, Sargent (the painter, John Singer Sargent) and Mme Maddison (Adela Maddison, Fauré’s English egeria) wept with emotion.’ The material of this arrangement 'unpublished and lost,’ according to Robert Orledges biography of Fauré, was for years in the collection of the late Anthony Bernard, including the autograph full score. ‘Une Sainte en son auréole’ sets the happy mood of the cycle with a motif which recurs throughout the song and reappears in four others before returning at the end of the last song. The poet lists a series of pictorial images evoked by the "Carlovingian name" of his beloved (Mathilde) clinched by the archaic associations of the final cadence, a reminder that Fauré, a product of the Ecole Niedermeyer, was schooled in the modes at an early age. A repeated note in the accompaniment of the second verse evokes the golden note of the horn in the depth of the forest. The unset verses of ‘Puisque I'aube grandit’ depict the night from which the poet was emerging to greet the dawn of a new way of life. Fauré's music begins with the hopeful ebullience of short notevalues in the accompaniment which, senza rallentando, change from triplet semiquavers to triplet quavers for the more steady progress towards Paradise in the last verse. The composer of so many piano nocturnes catches to perfection the nocturnal atmosphere of stillness and peace in La lune

blanche, the poem in which the poet addresses his loved one in the lines ending each of the three verses "O beloved... Let us dream, 'tis the hour...'tis the witching hour." A rising scale motif heard in the piano part at the end of La lune blanche informs the positive, forward movement of ‘J’allais par des chemins perfides’, once the composer has in each stanza put behind him those initial lines about the sadly insecure and treacherous paths the poet was following before Mathilde's dear hands led him onwards to be joined with her in the happiness depicted in the radiant ending of the song. In ‘J’ ai Presque peur’, repeated notes in the vocal line and accompaniment suggest the poets palpitating heart at this excessive joy gives rise to a kind of nervous anxiety at his good fortune. But at the end of the fifth stanza an obsessive melodic formula in the piano part seems to support and embolden the affirmation of his love. Each verse of ‘Avant que tu ne t'en ailles’ divides into two equal halves of two lines each, alternating the poets injunction to the morning star, to carry his thought to his beloved as she dreams, with his rapt description of dawn. Four of Fauré's recurrent motifs appear in this song, including a dotted‐note figure, associated with the ascending lark which is one of the four that reappear in the final song. ‘Donc, ce sera’ described a wedding‐day in high Summer, taking up the theme of the sun from the previous song. The only rallentando in the whole cycle prepares for the final verse, where with the nightfall the mood becomes less excited, more quiet and tender. ‘Nest‐ce pas?’ Conveys the peace and contentment of the couple as they tread the path of life together, "hand in hand, with the child‐like soul of those whose love is unalloyed". The lark motif announces L'hiver a cessé and the return of Spring. "Let the seasons return" sings the poet. Each will delight him. And, in ending, he addresses her who has coloured his fantasy and reason throughout. Fauré makes a musical epilogue of this last phrase, gathering up a number of the motifs heard in the previous songs as the cycle draws to its luminous close. Fauré was seventy seven when his publisher suggested that he should write a piano trio ‐ his first. In the Summer of 1922, while staying at Argeles, not very far from the birthplace of Ravel and of Ravel's Trio, Fauré asked for some sketches he had left on his table in Paris to be sent to him. They became the middle movements of his Trio. This Andantino he completed in September 1922, while staying with friends at Annecy‐le‐Vieux. The two outer movements were composed on his return to Paris, and the work was first performed there in June 1923, by the Thibaud‐Cartot‐Casals Trio. Beneath the gently rocking quavers of the piano part, the cello sings out, in D minor and triple‐time, the main theme of the movement. It is repeated by the violin, while the cello adds a counterpoint and the piano a firm boss line. The second subject, announced by the piano, hovers over subtle harmonic changes, like a butterfly over flowers, in a conject cantando. These two themes are projected clearly and effortlessly in the ensuing development which impresses less by its elaboration or any obvious fragmentation of this material than by its smooth forward flow in the modally tinged musical stream of which Fauré was a master. In the Andantino violin and cello answer each other before ending in duet over the piano's placid accompaniment in F major and common‐time. The piano takes the lead in the more insistent second theme. A contrasting middle section ‐ the first music of the Trio to be written ‐ with its gradually rising step, propels the music as surely forward as upward, again a characteristic of Fauré's later style. Recapitulation of this material is rounded off by a serene coda.

94750 Fauré Edition 4

The two thematic elements of the finale are previewed at the outset where the brusque octave call of the two strings is answered by the almost Bartokian answer of the piano before it breaks out into a lively movement of semiquavers in three‐eight time. This provides animated alternation for the downward thrusting octaves of the strings and pattering accompaniment to the second theme now heard on the cello. During the scherzo‐like course of the movement, these two elements are continually present even in canonic guise, eventually combining after the second theme has swung the music into the tonic D major for its happy ending. Florent Schmitt's comment on Fauré's Trio, his penultimate work, deserves quotation: "Thin as Rameua, serene and strong as Bach, tenderly persuasive as Fauré himself." CELLO SONATA IN D MINOR, OP.109 The first of Fauré's two cello sonatas was completed at Saint‐Raphael on the Cote d'Azur in August 1917, a year after the second violin sonata (during the Conservatoire years, composing was virtually confined to the holidays, when Fauré would stay in a modest hotel or with hospitable friends in Switzerland, in Savoy or on the Riviera). The opening theme has a dry, spiky quality unusual in Fauré, though foreshadowed in some of the piano Preludes, in parts of the opera Pénélope and recurring in the Fantaisie for piano and orchestra written not Iona after the sonata. In fact this theme was rescued from the early symphony of 1884, twice performed but never published, though listed as Op.40. In another form it appears in the scene for Ulysses at the beginning of act 3 of Pénélope. In the sonata's first movement the effect of the detached semiquavers in the cello and jagged, percussive accents in the piano part is set off by the gentle, rising second subject. The two themes are reconciled at the end of a second development placed after the recapitulation (a formal feature of Fauré's mature sonata movements). That this remarkable Allegro is so unlike the conventional idea of Fauré's chamber music is doubtless one reason for its neglect compared to the second sonata. The Andante is a grave meditation in G minor, the second theme modally coloured. Note the quietly varied texture of the outwardly simple piano writing. Now that Fauré was deaf and that hearing music was painful to him, there was no question of trying out his own work on the keyboard; it went straight down on to paper. He must have had an inner ear of exceptional acuteness. Beneath the calm surface of this Andante there is some canonic writing of far from orthodox effect. The finale redresses the balance of a mostly somber sonata with major tonality and themes of a contained exuberance for which the idea occurred face to face with a sunny sea "of unchanging blue". CELLO SONATA IN G MINOR, OP.117 One of Fauré's last works, written in 1921, the year of the 13th Barcarolle, the song cycle L'horizon Chimérique and the 13th Nocturne. One would never take it for the music of an ailing composer in his late seventies. The first movement bowls along in three‐four as if conceived in a single breath. There is barely time to notice the subtle, restrained contrast between the themes, or the skill and discretion with which Fauré uses such devices as imitation and sequences. Unlike the corresponding movement of the first sonata, this one closes in the major. The kernel and raison d'être of the G minor sonata is the slow movement. Fauré had recently composed a Chant Funéraire for military band, for a ceremony at the Invalides in Paris in honour of the centenary of Napoleon's death. It turned out too well to be left in a medium which did not promise many performances. Most composers would have re‐scored it for symphony orchestra. Fauré whose bent was for small instrumental combinations, decided to incorporate it in a cello sonata, framed with two

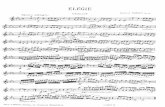

allegros. It is a nobly sustained lament in C minor, in the mood of the principal theme of the much earlier Elégie. The finale is a free rondo with the allure of a scherzo. The piano's glittering semi‐quavers are as fleet as the most mercurial pages in Verdi's Falstaff. In both sonatas, Fauré's writing for the cello exploits the instrument's finest qualities without any concession to facile virtuosity. ELÉGIE, OP.24 The best‐loved of Fauré's cello pieces. It was published in 1883, but there is reason to believe it may be the "morceau de violoncelle" referred to in a letter of 1880 from Fauré to his publisher, stating that the piece in question had originally been conceived as the slow movement of a sonata. This, apparently, was not completed. So the Elégie may be slightly earlier than publication date and opus number. STRING QUARTET In the first movement of the quartet the passionate‐gloomy elements of the viola are answered in phrases of light resignation by the first violin. The second idea, however, lightens the piece with its supple, rising shape. Fauré maintains the contrasts between the melodic ideas in a masterful polyphonic process. In the second movement the feelings of despondency appear to change into those of comfort, released form physical pain. Behind the grandly‐calculated harmonic progressions of the andante, a "smile veiled by tears" (J. Pesi) is just barely perceptible. The main theme of the finale is portrayed by a lively five bar phrase which is followed by another melodic idea, likewise in doubling octaves. And in the cello a new, sweet, melodic thought appears in a higher register, allowing for the introduction of a radiant coda in the major mode. Here the timbres particular to each instrument are pushed to their extreme. Using pizzicati, long phrases of different rhythms, and the orchestral coda‐effect to free every emotion. Fauré succeeded in bringing the three movements of the work together in harmonic unity in a kind of "dance of the blessed spirits" (P. Fauré‐Fremiet). VIOLIN SONATA NO.1 Fauré composed this beautiful, charming work full of life and lyricism in 1875 at the age of 35. Ravel, his future pupil, wrote that it was made for "incompatible instruments". The sonata begins with an Allegro molto, a perfect dialogue between the two instruments. The piano appears first, followed by the violin, hardly perceptible, beginning the dialogue. Fluid melodies and supple rhythms. During the whole work the obstacles are not so much technical (although there is nothing which is very easy) but the manner in which the two soloists communicate. Fauré's style remains: showing itself but never entirely. This could explain the lack of enthusiasm for his work in France ‐ whereas abroad he is often considered the French composer. The second movement, Andante, again creates a new soft and subtle dialogue. No brightness, no exaggeration, only softness which one finds also in the pages of the Requiem and certain melodies. The Allegro vivo, in the place of a Beethoven scherzo, is diabolical. Here the technique and the position of the instruments are delicate. Like an acrobatic without a net. As exquisite as later on the equivalent movements of the Quartet with piano are. It is not a paradox that the last movement, Allegro quasi presto, despite the note "quasi presto", if much more relaxing. The classical alternation of the form ABA, is paradoxical: a melodious line full of tenderness, it rests on a lively movement.

94750 Fauré Edition 5

Beginning with a rhythm close to Bach's gigues of the Partitas, leading to a second theme, bright, even glorious, as though the approach of the end allows the work to give full liberty to its vehemence. The work ends with different recurrences of the rhythmical theme in a quiet certitude, the composer's personal mark. VIOLIN SONATA NO.2 The second Violin Sonata in E minor was written more then 40 years after the first sonata, and brings us into the world of Fauré's late period, which was overshadowed by his increasing deafness. He started working on it in Evian at Lake Geneva in August 1916 and it was published in Paris in 1917. The sonata did not gain the popular appeal of the first sonata, which might be due to the much darker, more violent character of the music, an evocation of the anxiety of the period. The first movement is dominated by three contrasting themes, each of which is treated individually in the development section. The recapitulation is in a changed metre, and the coda presents the three themes again. The slow movement is a mixture of long‐drawn, serene melodies and slightly turbulent developments into more and more remote harmonies, so characteristic of late Fauré. The last movement is in sonata‐rondo form, in which thematic material from the first movement is included, suggesting a cyclical form. COMPLETE PIANO WORKS The fact that Verlaine found his composer in Gabriel Fauré – that Clair de lune from Fêtes galantes and La Bonne Chanson rank among the composer’s most outstanding successes – does not mean that Fauré should only been seen as the composer of hazy dreams, of quicksilver emotions, of startled outpourings for fair turn‐of‐the‐century listeners. The Nocturnes alone – composed over a span of almost 40 years (1883–1922) – would suffice to prevent any identification of the composer, trained in the rigorous discipline of the Niedermeyer School, with the impressionist poet. Verlaine delights in the uncertainty of feelings and landscapes, thereby entertaining a confusion between a hazy exterior and the irresolutions of an aching soul – a continuing game of deceit. In Fauré, on the other hand, one finds no such ambiguity: his consciousness does not allow itself to dissolve into a world where objects have completely lost their outline. Northern mists, a murky chiaroscuro, an unhealthy twilight, this is what suits Verlaine’s equivocal Nocturnes. Fauré is a man from the South: his Night retains all the luminosity and brightness of the Mediterranean, paths can be made out and emotions do not stray off into an uneasy twilight zone. In an attempt at lucidity similar to that of Marcel Proust, Fauré’s entire object seems to be to prevent the various states of consciousness he is seeking to plot with precision from dissolving, by freeing them from the host of casual sensations or secondary emotions that might submerge them. If indeed there is reverie (as at the opening of the third Nocturne), it asserts itself openly – for there is to be no mistake as to the meaning of these modulations and arabesques that, on a par with the melodic extension of Fauré’s musical argument, constitute the adverbial and parenthetical clauses without which, as in Proust’s long sentence, there would be no progression along the stream of consciousness – and under which the direction this takes is still perceptible. Fauré’s refusal to make allowances for gratuitous ornamentation, his insistence on ‘sustaining’ his musical argument at all costs, this is his supreme – classical – elegance: far removed from the salon variety. In the last Nocturnes, when meditation rises to an almost spiritual contemplation of nature,

the line of the phrase retains the same limpidity, the same luminosity. Jean‐Michel Nectoux has a point when he relates Fauré both to Vermeer and to Matisse. Fauré’s love of clarity and light is apparent in the nine Préludes, Op.103, from 1910, constituting a stock‐taking – in the form of images, of ‘miniatures’ – of his entire opus, as much from the point of view of harmony as from that of inspiration. The writing amazingly foreshadows an entire future trend in music, as for instance the Prélude No.1, almost completely abstract, with disturbing flights into atonality, or No.9, extraordinary immaterial, apparently composed in a sort of daze. Each of the others displays a distinct character: No.2 is a ‘spinner’s’ perpetual motion; No.4 allies the youth of Dolly and a theme later to appear in the minuet in Masques et bergamasques – a ‘novelette’ Poulenc was to remember; No.8 is a saltarello, No.5 could have been a discarded page from Pénélope (which Fauré was working on at the time); No.6 – a cantilena – strikes one as an organist’s improvisation in a sort of Offertory; No.3, humorously sketching out a belle époque waltz, as well as No.7, are nocturnes. Thème et Variations (1895) proves that, in a Conservatory examination piece, Fauré can match Bach for his purity of composition and Schumann for the emotion in his Symphonic Studies (Variations II, IV, VI and X). The listener will admire the extraordinary economy of means in Variation V (on simple broken scales) and VIII (a humble chorale). Fauré was 34 when he composed the Ballade in F sharp in 1879 – a work breathing youth and the sheer joy of being alive, so discreetly conveyed by the admirable opening theme. The continually renewed inspiration, the freedom of pace associating serenity and outright joy, the vigorous assertion of contentedness in the central motif, very reminiscent in tone of Franck, the entire atmosphere of warm, golden light invariably directs the listener’s thoughts to Auguste Renoir. © Philippe Mougeot Translation: Elizabeth Caroll The piano music of Gabriel Fauré reveals the richness of a personality capable of expressing itself equally happily in a whole variety of registers; whether in the suppleness and fluidity of the Barcarolles, the fantasy and dexterity of the Valses‐Caprices, the elegance and ease of the Impromptus, the lightness and concision of the Pièces brèves, the naive tenderness of the Romances sans paroles, the knowing glance at the children’s game of Dolly, or even the mischievous smile of the Souvenirs de Bayreuth, a quadrille on favourite themes from Richard Wagner’s Tetralogy, improvised in collaboration with André Messager. The first work for piano of a young man of 19, the Romances sans paroles date from 1864. The 13th Nocturne and the 13th Barcarolle were composed in 1921 when Gabriel Fauré was 76. Between the youthful charm of the first attempts and the accomplishment of Opus 116 and 119, one can see how far he has travelled. If he always fought shy of the picturesque, of demonstrations of virtuosity and displays of emotion, and if, apart from the occasional fitful enthusiasm, he never paid heed to the fashion of the day, least of all to impressionism, he nevertheless, like Chopin (the composer closest to him), brought to music ‘un frisson nouveau’ (a new thrill). The only titles Fauré borrowed from Chopin are Mazurka, Nocturnes, Preludes and Impromptu. This choice is a simple indication that one should not look in his work for either ‘literature’ or ‘philosophy’, but for music, and music alone. This music does not speak the same language as that of the Romantics. It denies itself obvious effects of contrast, preferring a continuous flow of sound to abrupt changes of tone.

94750 Fauré Edition 6

Playing on the richness of polyphonic composition and on suppleness of modulation, it creates nuances of a subtlety hitherto unknown. This, as the years passed by, led Gabriel Fauré towards an increasingly sober and reticent form of art, but one which became more and more vigorous as it progressed. The first Barcarolles, which begin as simple music for singing on the water, develop (Barcarolles Nos. 5 and 6) into music in the image of the water itself, quickened by the breath of the open sea, scintillating and capricious, then evolve towards a more concentrated idiom which retains only the essential features of the water’s image, its fluidity, its movement, to culminate in a meditation on the passage of time. At the end of the journey all that remains is the ‘horizon chimérique’ – that call of the beyond which Gabriel Fauré will evoke in his last cycle of mélodies on poems by Jean de La Ville Mirmont. © Jean Roy Translation: Denis Ogan MÉLODIES/LIEDER The Songs of Gabriel Fauré In an interview given late in his career, Gabriel Fauré said of his ‘mélodies’ or songs: “They have been sung very often. Not often enough to make my fortune, but far too often nevertheless; in fact my colleagues maintained that, having done so well with songs of this sort, I ought to devote my life to them!” And indeed Fauré’s songs appeared at frequent intervals throughout his life. The first was written in 1861 and the last in 1921, which means that the earliest have a lot in common with the ‘romances’ in the manner of the Second Empire, with their refrains and their simple ritornelli on the piano. The adolescent who wrote Mai or S’il est un charmant gazon was still under the influence of his masters Saint‐Saëns and Niedermeyer, and the choice of texts from Hugo and Gautier reflects what both of them had recommended him to read. These youthful pages, published from 1869 onwards, did not at a later date meet with their author’s unqualified approval: asked about them in 1911, Fauré readily admitted that he had “never succeeded in putting Victor Hugo into music”, despite the numerous texts he had borrowed from him. But these experiments with Romantic poetry had at least taught him that the grand manner of Hugo was less suited to him than four limpid stanzas from Leconte de Lisle: Lydia (1870) is a minor masterpiece which marks quite clearly the transition from ‘romance’ to ‘mélodie’; the latter being a more elaborate, more sophisticated form of composition, in which the song escapes the confines of straightforward narrative to enjoy richness of expression and comparative freedom. Thanks to Berlioz and Gounod, the French ‘mélodie’ had just acquired its letters patent: if it was still to be heard often enough in middle‐class drawing rooms, from now on it could ascend the concert platform without a blush. In Fauré’s work the ‘mélodie’ was to adopt a ternary construction through the frequent introduction of a second motif in the centre of the piece; the piano supports the voice, but enters into dialogue with it, too, the bass line serving a double purpose, harmonic and contrapuntal. The Franco‐Prussian war, in which the musician played a part, his meticulous reading of Schumann’s Lieder, and his momentous discovery of the songs of Duparc were to impart a sombre hue to Fauré’s muse, hitherto fairly light‐hearted. Seule!, L’Absent, La Rançon and Chant d’Automne form a group distinguishable by a melancholy and a severity not unconnected with Fauré’s researches into composition and form: in addition the musician has to contend ‐ with variable success – with the daunting modernity of Baudelaire.

The young composer’s introduction to the Viardot circle in 1872 was to effect a further stylistic transformation. La chanson du pêcheur, written for Pauline, looks in the direction of aria in the French manner, with something of the grand, declamatory, classical style about it. This success was followed by pages which make it clear that the young Fauré was being strongly encouraged by his hosts to cultivate vocal virtuosity and the ornate singing of the Italians; and here we must mention at least Sérénade toscane, Après un rêve, Barcarolle, and the brilliant Tarantella duet written for two of Pauline Viardot’s daughters, Claudie and Marianne. When the musician’s engagement with Marianne was broken off in 1877, this Italian period came to a somewhat abrupt conclusion. This major emotional upset possibly explains the sombre, often angry, character of numerous songs written around 1880, such as the triptych Poème d’un jour or Le voyageur, Automne, Les berceaux. But, parallel with these, Fauré is developing that discreetly lyrical, undulating and engaging style which made his name and his too often been seen as summing up his achievement: unjustly, for Fauré is not simply the composer of Les roses d’Ispahan or the Second Impromptu for piano! The two pages of Le secret (1881) are, for their flawlessness and their lyricism, much more promising: they herald the best of Fauré – which is far from being the Fauré who is most frequently heard. Reading the Fêtes galantes of Verlaine was for the musician a revelation; that subtle, chaste and yet sensuous artistry, whose melancholy is tinged with an elegant irony, offered a whole series of images in which he recognized himself. Clair de lune (1877) and Spleen (1888) are perfectly executed musical and poetic transpositions. In the Cinq mélodies op. 58, for which he made preliminary sketches in June 1891 during a dazzling visit to Venice, staying with Winnaretta Singer, Fauré happily rediscovered that universe, and broke new ground formally by giving the cycle a dual framework, literary and musical: he organized the texts into a love story, linking them, from one song to the next, by means of a single melodic motif and fragments from earlier passages. These experiments were to come to fruition in La bonne chanson (1892‐1984), a great cycle based on the poems of Verlaine, in which all the nuances of passion are evoked musically with a quite exceptional sureness of touch. What might rightly be called a lyrical symphony has six recurring themes running through it, without ever the complexity of form and language, hyperchromatic and with variable metre, reducing the emotive force which carries it forward. For once Fauré has cast aside that native reserve which is too often a restraint upon so unassuming a genius, to present us with a masterpiece bursting with energy, carried away by this passionate love for Emma Bardac, that inspired source of inspiration… During the last years of the century Fauré devoted himself to the theatre, although the comparatively few songs he wrote at that time are among his most perfect. One needs only mention Prison and Soir (1894), the duet Pleurs d’or of 1896 or Le parfum impérissable of 1897. At this stage Fauré’s style was evolving towards concision, counterpoint and transparency of composition. Harmony becomes less emphatic and is coloured with new dissonances. In his own discreet, unfussed, but determined way, Fauré is crossing the threshold into the idiom of the 20th century. In 1906 Fauré discovered the poetry of the great Belgian symbolist Charles van Lerberghe and undertook to provide a sort of pendant to the Bonne chanson with the Chanson d’Ève; his work on this continued patiently until 1910, while at the same time he was composing his opera Pénélope. Sobriety predominates in this new cycle, both in the accompaniment, all in contrapuntal lines, and in the vocal style, which comes near to a

94750 Fauré Edition 7

sort of recitative. Two themes underlie the melodic pattern. The first, a rising arpeggio, makes its appearance from the very first bars of the work; it comes from the coda of the Mort de Mélisande in the orchestral suite based on the Pelléas of Maeterlinck. The second, chromatic and modulating, appears a little later in the piano part, beneath the words “a blue garden emerges resplendent”. The at times hieratic singing, the limpid atmosphere streaked with pale northern light, throughout which the cycle evolves, receive some warmth, however, when Eve wakes to the disquieting beauties of this ultra‐symbolist Eden. Roses ardentes and Veilles‐tu ma senteur de soleil! introduce a strain of humanity, as does the second song with its admirable modal curves. Prima verba. The cycle closes on a superb piece in which the fascinating figure of Thanatos is portrayed in splendour: O Mort, poussière d’étoiles. Le jardin clos, the second cycle base on van Lerberghe’s poems, is not as musically and philosophically ambitious as its predecessor, but there is no doubt that it is more successful, possibly because the musician wrote it in just a few months, during the tragic summer and autumn of 1914. This time there are no recurrent themes, the songs are short, elliptical, sometimes to the point of abstraction, the writing subject to a remarkable economy of means. Here Fauré attains to absolute simplicity, but without the least aridity: music in its pure state. There is infinite tenderness in Je me poserai sur ton Coeur, fervour in the La messagère and Il m’est cher, Amour, that perfect sense of mystery so dear to Mallarmé in the final meditation, while Dans la nymphée figures, to my mind, among Fauré’s finest achievements; this song is dedicated to Claire Croiza who gave the cycle its first performance, with Fauré as accompanist. During the summer of 1919, which he spent in Annecy‐ le‐Vieux, Fauré wrote a cycle of four songs for the young Madeleine Grey, whose voice had captivated him. This was Mirages, based on some rather tame symbolist poems by Renée de Brimont, a grand‐nièce of Lamartine… There is little doubt that this nocturnal cycle is the one in which Fauré comes nearest to unifying song and text. The vocal style tends towards the spoken word; the voice, rarely other than piano, descends to almost a murmur; the music seems to derive from the very sound of the words. The accompaniment, fuller than in the Jardin clos, is of a quite distinctive harmonic richness and supports the voice as though step by step. The only brilliant piece, which comes last – Danseuse – is enlivened by a bewitching rhythmic ostinato. L’horizon chimérique, composed in 1921, is rather the opposite of the evanescent Mirages, the bold images of its seascapes dispelling with high winds and sea spray the noxious vapours of the docks at night. The tempi are modelled on the wild motion of the ocean swell, without disturbing the unique calm of the night‐time scene: Diane Selene; the voice recovers its fullness and the flexibility of its broadly drawn contours; the accompaniment shakes free from its reserve into a profusion of shapes and forms. In this compact and uniquely expressive cycle the musician recaptures the eloquence of those finest of chamber works which he had just composed: the Second Sonata for Cello and the Second Quintet. Drawing on the enthusiasm of the poet Jean de la Ville de Mirmont, who had died in the war while still very young, Fauré felt again the romantic fervour of his own early years. He was by now seventy‐five, but he was never so young as in this cycle which brought to a magnificent conclusion sixty years of song‐writing. © Jean‐Michel Nectoux Translation: Denis Ogan

REQUIEM Though he eventually became the director of the famous Paris Conservatoire de Musique, Gabriel Fauré was fairly unusual among the leading composers of his generation in that he was never a student there. Instead, from the age of nine, he was educated at L’École Niedermeyer, the independent school founded and run by the educationist Niedermeyer, and where Camille Saint‐Saëns also taught. Fauré graduated in 1865 with first prizes for piano, organ, harmonium and composition. It is significant that Niedermeyer placed great stress on church music, and on the study of the Gregorian modes, which hardly figured in the Conservatoire curriculum. This had a deep and lasting effect on Fauré’s melodic and harmonic language throughout his life, but it is especially noticeable in his sacred works. There are comparatively few of these: about a dozen Latin anthems, a Messe Basse for female voices and organ, and above all the Requiem, which was in fact his first setting of a religious text, and his only one on a large scale. Behind him lay the popular Ballade for piano and orchestra, the two piano quartets, and numerous piano works and songs, while most of his finest achievements lay ahead – such as the two piano quintets, the opera Pénélope, and the later song‐cycles. For a long time the origins of the Requiem were shrouded in obscurity and misinformation. It now seems that he wrote the original version of the Requiem when he was 42, from the autumn of 1887 to January 1888, starting with the ‘Pie Jesu’ movement. His father had died in July 1885 and the death of his mother took place in December 1887, while the work was being composed; it is sometimes stated that the work was written in memory of his father. Yet the first performance, which took place in the Madeleine Church in Paris in January 1888, was given in memory of the architect Joseph Le Soufaché. At this point the work was a ‘little’ requiem, lacking the Offertory movement and scored only for violas, cellos, organ, harp and timpani. For a second performance in 1888 Fauré added horns and trumpets. Then in 1891 he incorporated the ‘Libera me’, which had been composed independently for voice and organ as early as 1877, into the design, and made further revisions, enlarging the choral music of the first and last movements, in 1894. It was only in this latter year that the form we are now familiar with, scored for full orchestra, finally appeared: Fauré often consigned the task of orchestration to his pupils and the evidence suggests that this orchestral version, finally given its public premiere at the Paris Universal Exhibition in 1900, may in fact be wholly or partly by Jean‐Roger Ducasse (1873–1954), himself destined to become a distinguished composer. Although the Requiem has its dramatic moments, notably in the solemnly anguished appeal of the ‘Libera Me’, its predominant effect is of an ineluctable serenity. The setting of the mass is not liturgical, in that Fauré chose those sections which accorded with his own religious feelings. Fauré omitted the ‘Dies Irae’ entirely, and the ‘Liberame’ and ‘In Paradisum’ are drawn not from the Requiem Mass but from the Order of Burial. Fauré liked to quote Saint‐Evremond’s maxim that ‘the love of pleasure, and the avoidance of pain, are the first and most natural impulses observable in mankind’. As a result, Fauré maintained, ‘Art has therefore every reason to be voluptuous’. To some extent the Requiem is a product of that viewpoint. Fauré’s pupil Charles Koechlin, in his classic book on the composer, averred that ‘the indulgent and fundamentally good nature of the master had as far as possible to turn from the implacable dogma of eternal punishment’. Thus the Requiem is voluptuous and tranquil rather than stern or austere: indeed it might be said that it is not really a Christian work but rather a humanist acknowledgement of suffering and the need for comfort. (Brahms once declared that his German Requiem should have been called the Human Requiem.) However, the sensuous, almost Wagnerian harmony is held in tempered throughout by the more sombre colouring of

94750 Fauré Edition 8

the ancient church modes. The apparent simplicity and rectitude of its style conceal a compositional technique of unusual sophistication. The first six of the Requiem’s seven movements divide into three parts of two movements apiece, with the last movement, ‘In Paradisum’, forming an extended postlude. The elegiac and ritual aspects of the work are associated with the key of D, major or minor, while F major (D minor’s relative major) dominates the first and second, and the fifth and sixth movements. Between these two tonal blocks stand the ‘Sanctus’ (in E flat) and the ‘Pie Jesu’ (in B flat). Fauré’s original intention was that this movement should be sung by a boy. A change of texture (emphasized by the entry of the harps) confirms the special position of these two movements in the overall scheme of the work. The ‘Agnus Dei’, which follows the ‘Pie Jesu’, effects a return to the mood of the first two movements, a mood consummated in the funereal accents of the ‘Libera Me’. But the contrast between the ‘Libera Me’ and the final movement, ‘In Paradisum’ is, paradoxically, as radical as it is gentle. It returns us to the quietly ecstatic mood of the central movements. Emphasizing that return, the harps reappear; but the tonality is the elegiac D rather than the visionary E flat, thus resolving the subtle tonal tensions that have informed the entire work. As Koechlin observed, ‘thanks to the overflowing of his heart’, Fauré has created ‘ an aeterna requiem of … serene gentleness and consoling hope’. © Malcolm MacDonald, 2010 SACRED MUSIC Fauré's church music is intimately connected with one Paris church, the Madeleine, and its physical and social position in that city. Situated in a highly fashionable part of Paris, then (as now) it attracted a similarly fashionable congregation: anyone who was anyone got married there, and had their funeral there. Its traditions were not too ascetic, although its priests were renowned for their bad taste in music. In common with many better‐endowed French churches, the Madeleine employed two separate musicians: a titular organist responsible solely for the voluntaries, and not for the choir; and a choir organist, who conducted, or played a more modest organ, often at the other end of the church. The religious music on this recording is an example of this latter tradition, which may explain why, to English ears more accustomed to the English cathedral traditions of the 19

th century, the organ parts may seem

invariably modest. On the other hand, one of the first Madeleine organists in the 19th century had been the infamous Lefebure‐Wely, celebrated for his storm effects and gaudy operatic transcriptions. His successor was Saint‐Saens; his protégé Fauré deputised for and in turn succeeded him, initially as choirmaster. It was originally for the Madeleine that Fauré composed his celebrated Requiem; later arranged for a fuller orchestra, it was originally composed as a liturgical Mass for a particular parishioner's funeral. Fauré well knew how to write for the acoustics of the building, with its choir organ behind the altar, and many of the smaller motets heard here display a similar talent. His music follows on from Gounod and Saint‐Saëns rather

than allying itself with the plainsong revivalist tradition which was propagated at the Schola Cantorum. It is worth remembering that the Madeleine was only a stone's throw away from the Opera, and that its well‐heeled congregation was used to motets which owed more to the secular traditions there than to the austerity of plainsong. Think for example, of the rousing Libera me in the Requiem. Madeleine congregations were particularly fond of the harp, either in reality, as in the Requiem, or in emulation by the organ, as happens in several of the works on the current recording, including the Cantique de Jean Racine (where the young composer skilfully manipulates rather Mendelssohnian harmonies). The Messe basse is one religious piece not associated with the traditions of the Madeleine; indeed, Fauré saw the work as a moment of welcome respite. It is associated with the church of Villerville in Normandy, where in 1882 Fauré was staying with friends when he came across a local female choir; the encounter produced a somewhat impromptu but well‐sung performance of what was then known as the Messe des pecheurs de Villerville (Mass of the Villerville fishermen). This delightful work, on which Fauré had collaborated with Andre Messager, stayed in the private library of Fauré's friends the Clercs until 1907, when Fauré published the portions he had written under the title by which it is now known. Maria Mater Gratiae and Ecce fidelis servus are both Madeleine motets, while the Salve Regina was written for Emma Bardac, later to become Debussy's second wife. In all three a simple but meandering melodic line seems to be the guiding feature of the composition. The Madrigal, composed in 1882, dates from an era when it was fashionable to compose pieces with antique titles that alluded to the music of the 16th and 17

th centuries. There is little which is

really madrigalesque about the piece; rather does it allude to Bach, its first theme being a rhythmic reworking of the subject of the E flat minor fugue from Book 1 of the '48'. Pleurs d'or dates from 1896, and as a duet is rare in Fauré's output. Harmonically more subtle by a long chalk than the Madrigal, it is far distant from the more conventional language of ten years before, as is shown by comparison with Le ruisseau, which was written for an amateur vocal ensemble around 1880. Not that this piece is without charm, for there is little distance between Faure's secular and sacred styles in this genre. The Tantum ergo was a favourite choice for setting as an occasional motet. The first of the three examples heard here is the sole representative of the harp‐centred formula. The third Tantum ergo is more four‐square, while the Ave verum is again a Madeleine choir‐school piece. Of the feeling which emanates from this corner of the composer's output, Fauré's own comment cannot be bettered: 'However unimportant they may be, I put into them just the amount of human expression which it pleased me to.' © Richard Langham Smith, 1995

94750 Fauré Edition 9

Sung texts Texts marked with

‘i’ are not set by Fauré

CD 12 MÉLODIES I 1. Le Papillon et la fleur La pauvre fleur disait au papillon céleste: Ne fuis pas!... Vois comme nos destins sont différents, je reste. Tu t’en vas! Pourtant nous nous aimons, nous vivons sans les hommes, Et loin d’eux! Et nous nous ressemblons et l’on dit que nous sommes Fleurs tous deux! Mais hélas, l’air t’emporte, et la terre m’enchaine. Sort cruel! Je voudrais embaumer ton vol de mon haleine. Dans le ciel! Mais non, tu vas trop loin, parmi des fleurs sans nombre. Vous fuyez! Et moi je reste seule à voir tourner mon ombre. A mes pieds! Tu fuis, puis tu reviens, puis tu t’en vas encore Luire ailleurs! Aussi me trouves‐tu toujours à chaque aurore Tout en pleurs! Ah! pour que notre amour coule des jours fidèles. Ô mon roi! Prends comme moi racine ou donne‐moi des ailes Comme à toi! 2. Mai Puis‐que Mai tout en fleurs dans les prés nous réclame. Viens, ne te lasse pas de mêler à ton âme La campagne, les bois, les ombrages charmants, Les larges clairs de lune au bord des flots dormants: Le sentier qui finit où le chemin commence. Et l’air, et le printemps et l’horizon immense. L’horizon que ce monde attache humble et joyeux, Comme une lèvre au bas de la robe des cieux. Viens, et que le regard des pudiques étoiles, Qui tombe sur la terre à travers tant de voiles. Que l’arbre pénétré de parfum et de chants. Que le souffle embrasé de midi dans les champs; Et l’ombre et le soleil, et l’onde, et la verdure, Et le rayonnement de toute la nature, Fassent épanouir, comme une double fleur, La beauté sur ton front et l’amour dans ton coeur! 3. Rêve d’amour S’il est un charmant gazon Que le ciel arrose, Où naisse en toute saison Quelque fleur éclose, Où l’on cueille à pleine main Lys, chèvre‐feuille et jasmin, J’en veux faire le chemin Où ton pied se pose! S’il est un sein bien aimant Dont l’honneur dispose, Dont le ferme dévouement N’ait rien de morose, Si toujours ce noble sein Bat pour un digne dessein,

J’en veux faire le coussin Où ton front se pose! S’il est un rêve d’amour, Parfumé de rose, Où l’on trouve chaque jour Quelque douce chose, Un rêve que Dieu bénit, Où l’âme à l’âme s’unit, Oh! j’en veux faire le nid Où ton coeur se pose! 4. Dans les ruines d’une abbaye Seuls, tous deux, ravis, chantants, Comme on s’aime; Comme on cueille le printemps Que Dieu sème. Quels rires étincelants Dans ces ombres, Jadis pleines de fronts blancs, De coeurs sombres. On est tout frais mariés, On s’envoie Les charmants cris variés De la joie! Frais échos mèlés Au vent qui frissonne. Gaîté que le noir couvent Assaisonne. Seuls, tous deux... On effeuilles des jasmins Sur la pierre. Où l’abbesse joint les mains, En prière. On se cherche, on se poursuit, On sent croître Ton aube, Amour, dans la nuit Du vieux cloître. On s’en va se becquetant, On s’adôre, On s’embrasse à chaque instant, Puis encore, Sous les piliers, les arceaux, Et les marbres, C’est l’histoire des oiseaux Dans les arbres. 5. Les Matelots Sur l’eau bleue et profonde, Nous allons voyageant. Environnant le monde D’un sillage d’argent. Des îles de la Sonde, De l’Inde au ciel brulé, Jusqu’au pòle gelé! Nous pensons à la terre Que nous fuyons toujours. A notre vieille mère, A nos jeunes amours. Mais la vague légère Avec son doux refrain, Endort notre chagrin! Existence sublime, Bercés par notre nid. Nous vivons sur l’abime,

94750 Fauré Edition 10

Au sein de l’infini, Des flots rasant la cîme. Dans le grand désert bleu Nous marchons avec Dieu! 6. Lydia Lydia sur tes roses joues Et sur ton col frais et si blanc, Roule étincelant L’or fluide que tu dénoues; Le jour qui luit est le meilleur, Oublions l’éternelle tombe. Laisse tes baisers de colombe Chanter sur ta lèvre en fleur. Un lys caché répand sans cesse Une odeur divine en ton sein; Les délices comme un essaim Sortent de toi, jeune déesse. Je t’aime et meurs, ô mes amours. Mon âme en baisers m’est ravie! O Lydia, rends‐moi la vie, Que je puisse mourir, mourir toujours! 7. Hymne À la très chère, à la très belle, Qui remplit mon coeur de clarté, À l’ange, à l’idole immortelle, Salut en immortalité, Salut en immortalité! Elle se répand dans ma vie, Comme un air imprégné de sel, Et dans mon âme inassouvie, Verse le goût de l’Eternel. Sachet toujours frais qui parfume l’athmosphère d’un cher réduit, encensoir oublié qui fume en secret à travers la nuit. Comment, amor incorruptible, T’exprimer avec vérité? Grain de musc, qui gîs invisible, Au fond de mon éternité? À la très chère, à la très‐belle, Qui remplit mon coeur de clarté, À l’ange, à l’idole immortelle, Salut en immortalité, Salut en immortalité! 8. Seule! Dans un baiser, l’onde au rivage Dit ses douleurs: Pour consoler la fleur sauvage, L’aube a des pleurs; Le vent du soir conte sa plainte Aux vieux cyprès. La tourterelle au térébinthe Ses longs regrets. Aux flots dormants, quand tout repose, Hors la douleur, La lune parle, et dit la cause De sa pâleur.

Ton dôme blanc, Sainte‐Sophie, Parle au ciel bleu, Et, tout rêveur, le ciel confie Son rêve à Dieu. Arbre ou tombeau, colombe ou rose, Onde ou rocher, Tout, ici‐bas, a quelque chose Pour s’épancher: Moi, je suis seul, et rien au monde Ne me répond, Rien que ta voix morne et profonde, Sombre Hellespont! 9. L’absent Sentiers où l’herbe sa balance, Vallons, côteaux, bois chevelus, Pourquoi ce deuil et ce silence? “Celui qui venait ne vient plus!” Pourquoi personne à ta fenêtre? Et pourquoi ton jardin sans fleurs? Ô maison où donc est ton maître? “Je ne sais pas! il est ailleurs.” Chien veille au logis! “Pourquoi faire? La maison est vide à présent!” Enfant qui pleures‐tu? “Mon père!” Femme, qui pleures‐tu? “L’absent!” Où donc est‐il allé? “Dans l’ombre!” Flots qui gémissez sur l’écueil, D’où venez‐vous? “Du bagne sombre!” Et qu’apportez‐vous? “Un cerceuil!” 10. L’Aurore L’aurore s’allume, L’ombre épaisse fuit; Le rêve et la brume Vont où va la nuit; Paupières et roses S’ouvrent demi‐closes; Du réveil des choses; On entend le bruit. Tout chante et murmure, Tout parle à la fois, Fumée et verdure, Les nids et les toits; Le vent parle aux chênes, L’eau parle aux fontaines; Toutes les haleines Deviennent des voix! Tout reprend son âme, L’enfant son hochet, Le foyer sa flamme, Le luth son archet; Folie ou démence, Dans le monde immense, Chacun recommence Ce qu’il ébauchait. Qu’on pense ou qu’on aime, Sans cesse agité, Vers un but suprème, Tout vole emporte; L’esquif cherche un môle, L’abeille un vieux saule

94750 Fauré Edition 11

La boussole un pôle, Moi la vérité. Ô terre! ô merveilles Dont l’éclat joyeux Emplit nos oreilles, Éblouit nos yeux! Bords où meurt la vague, Bois qu’un souffle élague, De l’horizon vague Plis mystérieux! Saint livre où la voile Qui flotte en tous lieux, Saint livre où l’étoile Qui rayonne aux yeux, Ne trace, ô mystère! Qu’un nom solitaire, Qu’un nom sur la terre, Qu’un nom dans les cieux! 11. La rançon L’homme a, pour payer sa rançon Deux champs au tuf profond et riche, Qu’il faut qu’il remue et défriche Avec le fer de la raison Pour obtenir la moindre rose, Pour extorquer quelques épis, Des pleurs salés de son front gris, Sans cesse il faut qu’il les arrose! L’un est l’Art et l’autre, l’Amour: Pour rendre le juge propice, Lorsque de la stricte justice Paraitra le terrible jour, Il faudra lui montrer des granges Pleines de moissons et de fleurs, Dont les formes et les couleurs Gagnent le suffrage des Anges. 12. Chant d’automne Bientôt nous plongerons dans les froides ténêbres, Adieu vive clarté de nos étés trop courts! J’entends déjà tomber, avec [un choc funèbre]

i,

Le bois retentissant sur le pavé des cours. Tout l’hiver va rentrer dans mon être: colère, Haine, frissons, horreur, la beur dur et forcé, Et, comme le soleil dans son enfer polaire, Mon coeur ne sera plus qu’un bloc rouge et glacé. J’écoute en frémissant chaque bûche qui tombe; L’échafaud qu’on bâtit n’a pas d’écho plus sourd. Mon esprit est pareil à la tour qui succombe Sous les coups du bélier infatigable et lourd. Il me semble, bercé par ce choc monotone, Qu’on cloue en grande hâte un cercueil quelque part! Pour qui? c’était hier l’été; voici l’automne! Ce bruit mystérieux sonne comme un départ! J’aime, de vos longs yeux, la lumière verdâtre. Douce beauté! mais aujourd’hui tou m’est amer! Et rien ni votre amour ni le boudoir, ni l’âtre, Ne me vaut le soleil rayonnant sur la mer! [Et pour tant aimez moi, tendre coeur! soyez mère, Même pour un ingrat, même pour un méchant; Amante ou soeur, soyez la douceur éphémère D’un glorieux automne ou d’un soleil couchant.

Courte câche! La tombe attend; elle est a vide! Ah! laissez moi, mon front posé sur vos genoux, Goûter, en regrettant l’été blanc et torride, De l’arrière saison le rayon jaune et doux!]

i

1. not set by Fauré 13. Aubade L’oiseau dans le buisson À salué l’aurore, Et d’un pâle rayon L’horizon se colore, Voici le frais matin! Pour voir les fleurs à la lumière, S’ouvrir de toute part, Entr’ouvre ta paupière, Ô vierge au doux regard! La voix de ton amant A dissipé ton rêve; Je vois ton rideau blanc Qui tremble et se soulève, D’amour signal charmant! Descends sur ce tapis de mousse La brise est tiède encor, Et la lumière est douce, Accours, ô mon tresor! 14. Tristesse Avril est de retour, La première des roses, De ses lèvres micloses, Rit au premier beau jour, La terre bien heureuse S’ouvre et s’épanouit Tont aime, tout jouit, Hélas! j’ai dans le coeur Une tristesse affreuse! Les buveurs en gaité, Dans leurs chansons vermeilles, Célébrent sous les treilles Le vin et la beauté, La musique joyeuse, Avec leur rire clair, S’éparpille dans l’air. Hélas! j’ai dans le coeur Une tristesse affreuse! En déshabillé blanc Les jeunes demoiselles S’en vont sous les tonnelles Au bras de leur galant, La Inne langoureuse Argente leurs baisers Longuement appuyés, Hélas! j’ai dans le coeur Une tristesse affreuse! Moi je n’aime plus rien. Ni l’homme ni la femme, Ni mon corps, ni mon âme, Pas même mon vieux chien: Allez dire qu’on creuse Sous le pâle gazon Une fosse sans nom. Hélas! j’ai dans le coeur Une tristesse affreuse!

94750 Fauré Edition 12

15. Chanson du pêcheur (Lamento) Ma belle amie est morte, Je pleurerai toujours; Sous la tombe elle emporte Mon âme et mes amours. Dans le ciel, sans m’attendre, Elle s’en retourna; L’ange qui l’emmena Ne voulut pas me prendre. Que mon sort es amer! Ah! sans amour s’en aller sur la mer! La blanche créature Est couchée au cercueil; Comme dans la nature Tout me paraît en deuil! La colombe oubliée Pleure et songe à l’absent; Mon âme pleure et sent Qu’elle est dépareillée. Que mon sort est amer! Ah! sans amour s’en aller sur la mer! Sur moi la nuit immense Plane comme un linceul, Je chante ma romance Que le ciel entend seul. Ah! comme elle était belle, Et combien je l’aimais! Je n’aimerai jamais Une femme autant qu’elle Que mon sort est amer! Ah! sans amour s’en aller sur la mer! S’en aller sur la mer! 16. Barcarolle Gondolier du Rialto Mon château c’est la lagune, Mon jardin c’est le Lido. Mon rideau le clair de lune. Gondolier du grand canal, Pour fanal j’ai la croisée Où s’allument tous les soirs, Tes yeux noirs, mon épousée. Ma gondole est aux heureux, Deux à deux je la promène, Et les vents légers et frais Sont discret sur mon domaine. J’ai passé dans les amours, Plus de jours et de nuits folles, Que Venise n’a d’ilots Que ses flots n’ont de gondoles. 2 Duos pour deux sopranos 17. I Puisqu’ici‐bas toute âme Puisqu’ici‐bas toute âme Donne à quelqu’un Sa musique, sa flamme, Ou son parfum; Puisqu’ici‐bas chaque chose Donne toujours Son épine ou sa rose A ses amours; Puisqu’avril donne aux chênes Un bruit charmant; Que la nuit donne aux peines L’oubli dormant.

Puisque l’air à la branche Donne l’oiseau; Que l’aube à la pervenche Donne un peu d’eau; Puisque, lorsqu’elle arrive S’y reposer, L’onde amère à la rive Donne un baiser; Je te donne, à cette heure, Penché sur toi, La chose la meilleure Que j’ai en moi! Reçois donc ma pensée, Triste d’ailleurs, Qui, comme une rosée, T’arrive en pleurs! Reçois mes voeux sans nombre, O mes amours! Reçois la flamme ou l’ombre De tous mes jours! Mes transports pleins d’ivresses, Pur de soupçons, Et toutes les caresses De mes chansons! Mon esprit qui sans voile Vogue au hazard, Et qui n’a pour étoile Que ton regard! Ma muse, que les heures Bercent rêvant Qui, pleurant quand tu pleures, Pleure souvent! Reçois, mon bien céleste, O ma beauté, Mon coeur, dont rien ne reste, L’amour ôté! 18. II Tarentelle Aux cieux la lune monte et luit. Il fait grand jour en plein minuit. Viens avec moi, me disait‐elle Viens sur le sable grésillant Où saute et glisse en frétillant La tarentelle... Sus, les danseurs! En voila deux; Foule sur l’eau, foule autour d’eux; L’homme est bien fait, la fille est belle; Mais gare à vous! Sans y penser, C’est jeu d’amour que de danser La tarentelle... Doux est le bruit du tambourin! si j’étais fille de marin Et toi pêcheur, me disait‐elle Toutes les nuits joyeusement Nous danserions en nous aimant La tarentelle... 19. Ici‐bas! Ici‐bas tous les lilas meurent, Tous les chants des oiseaux sont courts, Je rêve aux étés qui demeurent Toujours!

94750 Fauré Edition 13

Ici‐bas les lèvres effleurent Sans rien laisser de leur velours, Je rêve aux baisers qui demeurent Toujours! Ici‐bas, tous les hommes pleurent Leurs amitiés ou leurs amours; Je rêve aux couples qui demeurent; Toujours! 20. Au bord de l’eau S’asseoir tous deux au bord du flot qui passe, Le voir passer, Tous deux s’il glisse un nuage en l’espace, Le voir glisser, À l’horizon s’il fume un toit de chaume Le voir fumer, Aux alentours si quelque fleur embaume S’en embaumer, Entendre au pied du saule où l’eau murmure L’eau murmurer, Ne pas sentir tant que ce rêve dure Le temps durer. Mais n’apportant de passion profonde Qu’à s’adorer, Sans nul souci des querelles du monde Les ignorer; Et seuls tous deux devant tout ce qui lasse Sans se lasser, Sentir l’amour devant tout ce qui passe Ne point passer! 21. Sérénade Toscane Ô toi que berce un rêve enchanteur, Tu dors tranquille en ton lit solitaire, Éveillei‐toi, regarde le chanteur, Esclave de tes yeux, dans la nui claire! Éveille‐toi mon âme, ma pensée, Entends ma voix par la brise emportée: Entends ma voix chanter! Entends ma voix pleurer, dans la rosée! Sous ta fenêtre en vain ma voix expire. Et chaque nuit je redis mon martyre, Sans autre abri que la voùle étoilée. Le vent brise ma voix et la nuit est glacée: Mon chant s’éteint en un accent suprême, Ma lèvre tremble en murmurant je t’aime. Je me peux plus chanter! Ah! daigne te montrer! daigne apparaitre! Si j’étais sûr que tu ne veux paraître Je m’en irais, pour t’oublier, demander au sommeil De me bercer jusqu’au matin vermeil, De me bercer jusqu’à ne plus t’aimer! 22. Après un rêve Dans un sommeil que charmait ton image Je rêvais le bonheur, ardent mirage, Tes yeux étaient plus doux, ta voix pure et sonore, Tu rayonnais comme un ciel éclairé par l’aurore; Tu m’appelais et je quittais la terre Pour m’enfuir avec toi vers la lumière, Les cieux pour nous entr’ouvraient leurs nues, Splendeurs inconnues, lueurs divines entrevues, Hélas! Hélas! triste réveil des songes Je t’appelle, ô nuit, rends moi tes mensonges, Reviens, reviens radieuse, Reviens ô nuit mystérieuse!

23. Sylvie Si tu veux savoir ma belle, Où s’envole à tire d’aile, L’oiseau qui chantait sur l’ormeau? Je te le dirai ma belle, Il vole vers qui l’appelle Vers celui‐là Qui l’aimera! Si tu veux savoir ma blonde, Pourquoi sur terre, et sur l’onde La nuit tout s’anime et s’unit? Je te le dirai ma blonde, C’est qu’il est une heure au monde Où, loin du jour, Veille l’amour! Si tu veux savoir Sylvie, Pourquoi j’aime a la folie Tes yeux brillants et langoureux? Je te le dirai Sylvie, C’est que sans toi dans la vie Tout pour mon coeur N’est que douleur! 24. Le Voyageur Voyageur, où vas‐tu, marchant Dans l’or vibrant de la poussière? ‐ Je m’en vais au soleil couchant, Pour m’endormir dans la lumière. Car j’ai vécu n’ayant qu’un Dieu, L’astre qui luit et qui féconde. Et c’est dans son linceul de feu Que je veux m’en aller du monde! ‐ Voyageur, presse donc le pas: L’astre, vers l’horizon, décline... ‐ Que m’importe, j’irai plus bas L’attendre au pied de la colline. Et lui montrant mon coeur ouvert. Saignant de son amour fidèle. Je lui dirai: j’ai trop souffert: Soleil! emporte‐moi loin d’elle! 25. Automne Automne au ciel brumeux, aux horizons navrants. Aux rapides couchants, aux aurores pâlies, Je regarde couler, comme l’eau du torrent, Tes jours faits de mélancolie. Sur l’aile des regrets mes esprits emportés, Comme s’il se pouvait que notre âge renaisse!‐ Parcourent, en rêvant, les coteaux enchantés, Où jadis sourit ma jeunesse! Je sens, au clair soleil du souvenir vainqueur, Refleurir en bouquet les roses deliées, Et monter à mes yeux des larmes, qu’en mon coeur, Mes vingt ans avaient oubliées!

94750 Fauré Edition 14

CD 13 MÉLODIES II Poèmes d’un jour 1. I Rencontre J’étais triste et pensif quand je t’ai rencontrée, Je sens moins aujourd’hui mon obstiné tourment; Ô dis‐moi, serais‐tu la femme inespérée, Et le rêve idéal poursuivi vainement? Ô, passante aux doux yeux, serais‐tu donc l’amie Qui rendrait le bonheur au poète isolé, Et vas‐tu rayonner sur mon âme affermie, Comme le ciel natal sur un coeur d’exilé? Ta tristesse sauvage, à la mienne pareille, Aime à voir le soleil décliner sur la mer! Devant l’immensité ton extase s’éveille, Et le charme des soirs à ta belle âme est cher; Une mystérieuse et douce sympathie Déjà m’enchaîne à toi comme un vivant lien, Et mon âme frémit, par l’amour envahie, Et mon coeur te chérit sans te connaître bien! 2. II Toujours Vous me demandez de ma taire, De fuir loin de vous pour jamais, Et de m’en aller, solitaire, Sans me rappeler qui j’aimais! Demandez plutôt aux étoiles De tomber dans l’immensité, À la nuit de perdre ses voiles, Au jour de perdre sa clarté, Demandez à la mer immense De dessécher ses vastes flots, Et, quand les vents sont en démence, D’apaiser ses sombres sanglots! Mais n’espérez pas que mon âme S’arrache à ses âpres douleurs Et se dépouille de sa flamme Comme le printemps de ses fleurs! 3. III Adieu Comme tout meurt vite, la rose Déclose, Et les frais manteaux diaprés Des prés; Les longs soupirs, les bienaimées, Fumées! On voit dans ce monde léger Changer, Plus vite que les flots des grèves, Nos rêves, Plus vite que le givre en fleurs, Nos coeurs! À vous l’on se croyait fidèle, Cruelle, Mais hélas! les plus longs amours Sont courts! Et je dis en quittant vos charmes, Sans larmes, Presqu’au moment de mon aveu, Adieu! 4. Nell Ta rose de pourpre à ton clair soleil, Ô Juin. Étincelle enivrée, Penche aussi vers moi ta coupe dorée: Mon coeur à ta rose est pareil.