8_sept_T&S

-

Upload

jose-bernal -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of 8_sept_T&S

-

7/23/2019 8_sept_T&S

1/7

When are intelligent sensor environments successful?

Leo Pennings a,1, Thijs Veugen a,b,*, Annemieke de Korte a

a TNO Information and Communication Technology, Delft, The Netherlandsb Multimedia Signal Processing group of Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands

Keywords:Adoption

Applications

Intelligent sensor

Privacy

Sensors

Social acceptance

a b s t r a c t

The success of an intelligent sensor environment is mainly determined by the extent towhich it is adopted by users. In order to understand how the adoption process works and

when it is likely to be successful, we developed a general adoption model and applied it to

the four main categories. Based on four case studies, we developed and tested question-

naires that contribute as an instrument for evaluating existing sensor environments, or

during the design phase. It turns out that each specic type of intelligent sensor envi-

ronment has its own adoption issues.

2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

In todays society, sensor information is increasingly

used to support decision-making processes. One example issensors that measure the humidity and stability of dikes for

water management and to help Dutch engineers foresee

a possible collapse of the dikes. Another example is the

mobile phone, to which information about a product of

interest to a customer can be sent to attract his or her

attention.

An environment inwhichsensor information is used and

processed in a less straightforward manner to support

human decision making is called an intelligent sensor

environment. Such an environment usually consists of

a sensor access network for creatingand transporting sensor

information; a sensor informationinfrastructurefor storage,

computation, transformation, and commercial transactionof sensorinformation; and users whoworkin the intelligent

sensor environment or purchase sensor information.

In this paper we are especially interested in the users of

intelligent sensor environments. How do they experience that

environment? Users have an important say in the success or

failure of new intelligent sensor environments. This paper

provides insight into the process of adoptionor rejection. Such

information is useful for people who are concerned with the

success of their intelligent sensor environment.

2. Adoption model

Before developing a model for the adoption of intelligent

sensor environments, we studied a number of existing

models of user acceptance of new technology. The models

were developed from different perspectives of user accep-

tance, such as individual aspects of adoption, risk and trust

perspectives, constructive technology assessment, domes-

tication, and the innovation diffusion theory. Our general

model integrates elements from these various models.

2.1. Theoretical background

First, we summarize various models of user acceptance

of technology.

Individual adoption models d focus on the individual,

and ask which aspects play a role in the acceptance of

new technology as seen from the perspective of the

individual? In 1989, Davis[1]developed the Technology

Acceptance Model, which has since been extended by

various researchers. One of the most detailed models is

* Corresponding author. TNO Information and Communication Tech-

nology, Delft, The Netherlands. Tel.: 31 15 285 7314; fax: 31 15 285

7382.

E-mail address:[email protected](T. Veugen).1 Leo Pennings died on 13 March 2009.

Contents lists available atScienceDirect

Technology in Society

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / t e c h s o c

0160-791X/$

see front matter

2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2010.07.009

Technology in Society 32 (2010) 197203

mailto:[email protected]://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/0160791Xhttp://www.elsevier.com/locate/techsochttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2010.07.009http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2010.07.009http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2010.07.009http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2010.07.009http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2010.07.009http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2010.07.009http://www.elsevier.com/locate/techsochttp://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/0160791Xmailto:[email protected] -

7/23/2019 8_sept_T&S

2/7

Venkateshs Unied Theory of Acceptance and Use of

Technology[2].

Risk and trust perspectives d deal with a persons basic

level of trust, that is, trust in the specic technology at

hand, and/or trust in the actors involved in the devel-

opment and supply of the technology. An example of

these theories is a study by Cho in which risk and trust

perspectives were related to aspects of individual

adoption models[3].

Constructive technology assessment d a theory on the

methodology for developing new technologies. The idea

is to test the impact and acceptance of a new technology

as early as possible in its development, taking into

account all the actors involved. This includes not only

developers and end users but also society in general, in

order to become aware of existing views and opinions

in society on specic technologies or developments in

technology[4].

Domestication d explores how specic groups of

people (e.g., elderly people) acquire new technologies

and integrate them into their lives. Various phases of

domestication have been identied. For our general

model, we have selected four phases as identied by

Zhao: imagination (awareness and image building),

appropriation (acquisition), objectication (use), and

conversion (integration into ones personal life)[57].

Innovation Diffusion Theory d a theory developed by

Rogers [8] that identies a link between individual

models of adoption on the one hand and domestication

on the other hand. The theory can be summarized by

a bell curve, which identies different types of people

with regard to the adoption of new technologies. Rogers

identies ve categories of people in the innovation

diffusion process: innovators (2.5%), early adopters

(13.5%), early majority (34%), late majority (34%), and

laggards (16%). Rogers also identied ve phases in the

adoption process. The category to which a person

belongs determines how he or she proceeds through

these phases. The ve phases (although named differ-

ently) correspond more or less to the phases identied

in domestication theory: knowledge, persuasion, deci-

sion, implementation, and conrmation.

2.2. General model

The core of the general model for the adoption of intel-

ligent sensor environments consists of an integration of

building blocks from different models of user acceptance of

technology. The building blocks are grouped in four clus-

ters: Preconditions, Trust, Acceptance, (phases in) Adoption.

In addition, the model includes context aspects that could

inuence how individuals or groups of people react to new

technology applications. We describe the four clusters in

more detail below, andFig. 1illustrates the model.

2.2.1. Building blocks for the general model

Preconditions d This cluster contains a persons general

characteristics plus the typology of a person in terms of

his general willingness to innovate (based on Rogers

typology). A keyelement is the persons experience with

the technology at hand, or experience with technology

in general. Another element is the freedom to choose: to

what extent is the choice to use the technology based on

free choice, or is the user in a situation that makes it

difcult for him to reject the technology? This is

particularly important in work settings (the boss

dictates the use of the new technology) or in cases

where the use of the new technology is regulated by law

or government rules. Finally, people have limited pro-

cessing capacity, which means that a person has

temporary saturation levels with regard to his ability to

change and to accept new technology.

Trust d This cluster includes elements from the risk and

trust perspective. People differ in their basic level of

trust, with some having a higher level of trust than

others. Here, then, the issue is: how readily will an

individual be able or willing to trust another person,

a company, or an organisation? How does the individual

handle peer pressure, or the inuence of peers on

a persons opinion-forming. What kind of risks does

a person associate with a technological application or

the acquisition and use of this application? Different

types of risk can be distinguished: possible bad perfor-

mance by the product, time required to get to know the

application, high costs involved in the maintenance of

the product, possible negative psychological effects such

as social implications or privacy attacks involved with

the project. Creditability and behaviour of the supplier:

to what extent do users believe the suppliers good

intentions and efforts to do what is best for customers?

Acceptance d This cluster refers to individual adoption

models. For acceptance it is important to know what the

users expectations are with regard to the performance

of the application: to what extent will the application

enhance an individuals performance? Of equal impor-

tance is the estimation by the users of how much time

and effort is needed to become familiar with the new

application and learn how to use it? Social inuence has

a considerable effect on acceptance; will a person be

inuenced in a positive or negative way by his or her

peers? Facilitating conditions: the extent to which

a person believes that he or she will have access to the

right support to use the technological application.

Adoption d This cluster contains the four phases of the

domestication model, which have been adjusted

slightly:

- Image building: the phase in which the user becomes

aware of the existence of the new technology and

formulates opinions about it.

- Acquisition: the phase in which the user decides to

buy (or not to buy) the new technology.

- Use: the phase in which the new application is used

and in which the user experiments with different

functions.

- Integration: the phase in which the new technology is

incorporated into the persons daily life.

2.2.2. Building blocks outside the core of the general model

The general model shows four related aspects that are

outside the core of our model but still inuence the even-

tual success or failure of an intelligent sensor environment.

L. Pennings et al. / Technology in Society 32 (2010) 197203198

-

7/23/2019 8_sept_T&S

3/7

Technical aspects d The technical aspects of intelli-

gent sensor environments involve the technical

implementation of the system. The technical aspects

are important for the success or failure of an intelli-

gent sensor environment because they relate to scal-

ability, user friendliness, interoperability with other

systems, technical security risks, privacy and storage

of personal information, speed of performance, costs

of implementation, management and usage, and the

like.

Policy and legal aspects d Various policy instruments

might be applicable to the use and adoption of new

sensor technologies. On the one hand, specic laws or

regulation might restrict the use or impact of sensor

technologies. On the other hand, specic laws or regu-

lations might stimulate the use of this technology by

enforcing its use. Policy instruments might also be

coordination measures aimed at self-regulation or co-

regulation. In this context, the government might raise

awareness by providing information on new intelligent

sensor applications or by formulating guidelines. The

government might play a specic role in stimulating the

acceptance and adoption of intelligent sensor applica-

tions by acting as a launching customer (by aggregation

of demand or by specic acquisition of new innovative

technology). Finally, we should not forget that the

government can decide not to intervene, and let the

market mechanism do its work.

Societal and cultural aspects d The future success of

innovations depends on their institutional context,

on the interference and interdependency with their

social cultural environment. This successdor possible

failuredis difcult to predict and judge because of the

complexity of its embeddingin the(social) system.Social

and cultural trends are important drivers of adoption of

innovation and the possible direction of social change.

Trends offer a previewdsometimes merely a glimp-

sedof future needs in society. In recent decades we have

learned that, in many situations, a technology push

approach often came with a high risk of commercial

failure. When following a technology pull approach,

people are more likely to adopt (and even embrace) the

technological innovations that meet their needs. This

requires serious research into peoples needs, or the

improved organisation of their involvement in the

innovation process.

Concerning future innovations, there is not yet a reality

that can be studied. Previous research shows that it is

dif

cult for survey respondents, such as focus groups, toimagine what future innovations will look like and what

benets they will bring. In the early 1990s, when people

were asked about the use of mobile phones, they said they

would not really need one or would consider its benets to

be minimal. Within a decade, the majority of people in the

Western world owned a mobile phone and used it every-

where. Analyses of social and cultural contexts help orga-

nisations to develop their commercial intuition in terms of

spotting new business opportunities and predicting the

successof innovations.

Economic aspects d Financial measurements, such as

tax regulations, subsidies or loans might support the use

of intelligent sensor technologies.

Fig. 1. The general model.

L. Pennings et al. / Technology in Society 32 (2010) 197203 199

-

7/23/2019 8_sept_T&S

4/7

3. Instrument for examination

We have developed an instrument for examining

intelligent sensor environments. It can be used ex-postas

well asex-antewith regard to the introduction and appli-

cation of an intelligent sensor environment. The tool

consists of a lengthy questionnaire that contains questions

related to all the elements from the general model. In

addition, a manual has been developed for conducting

surveys based on this questionnaire. The manual also

contains guidelines on how to interpret the results from

completed questionnaires in relation to the general

conceptual model.

In the questionnaire, all the elements from the general

conceptual model have been translated into questions,

which makes it a good basis for surveys. However, in many

cases the questionnaire will be too extensive for a specic

survey, but it is possible to select specic questions from

the main questionnaire and use them in a survey or

personal interviews. The questions can be selected in

relation to the application at hand or the specic context of

the dedicated survey.

4. Four social contexts as a framework for analyses

We discuss four main categories of intelligent sensor

environments, mainly from a users point of view. Each

category is illustrated with a case. In order to gain new

insights into the future adoption of sensor networks and

applications in different social contexts, we studied four

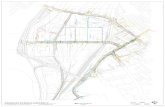

distinctive social contexts (seeFig. 2).

The rst distinction in the framework for our case

studies is a macro orientation whereby the party that

benets is either an organisation or society as a whole

(business or government), versus a micro orientation

whereby the use of sensor networks is designed to benet

a single individual as a consumer or citizen.

The second criterion for choosing interesting and rele-

vant case studies was the difference between aspecic use

for a small group (niche market) and a broader group

(general usage).

The dimensions for the four categories are similar to the

general model that we discussed in the previous section.

Now we can analyse the four cases in terms of the general

model. The two dimensions in the framework resulted in

the following four cases, representing equal (future) social

contexts for the adoption and use of intelligent sensor

networks.

Each of the selected cases is characterised by three

perspectives: nancial, social, and security. In each case,

our research focused on specic drivers and barriers that

are likely to inuence future success or failure. Additionally,

analyses of social trends provided us with greater insight in

each category. This eldwork focused our knowledge and

insight and can be applied in the future development of

services.

4.1. Case #1: intelligent sensors to improve quality of safetyd

the IJkdijk

The Dutch IJkdijk programme is a national test envi-

ronment for the development of intelligent dike protection

systems. Dikes, sensor technology, and scientic models

are tested in controlled conditions. A consortium of busi-

nesses, institutions, and water administrators examines the

practical application of sensor technology to support water

management, making use of new enabling technologies.

This programme aims at more efcient control and even-

tually a real-time monitoring system for dikes. Research in

this programme will contribute to the development of early

warning systems for existing and new dikes. The IJkdijk

programme is also used to review innovative technologies

and concepts that will enable an improved and/or more

robust design of the infrastructure[9].

Using sensors to improve the quality of a critical envi-

ronmental process, such as guarding dikes to prevent

oods or other disasters, the IJkdijk project represents an

intelligent sensor to improve safety standards.

We called this category RoboCop because it involves

a hybrid combination of a natural dike (the Cop) with

embedded sensor technology (the Robot), both functioning

together as an automated system. If this could be consid-

ered an archetype, another example is smart energy

metering.

4.2. Case #2: intelligent sensors to enable new information

services on a national leveldthe National Data Warehouse

In this example, intelligent sensor systems generate

trafc data and patterns at the national level. The govern-

ment uses measured data such as speed, travel time, and

trafc congestion to manage trafc and to provide infor-

mation services to motorists. All data are gathered in

a National Data Warehouse (NDW) and are subsequently

enriched, for example, with data on mobile phone use. This

data must meet high qualitative standards. It is provided

for road and trafc management purposes, but also for

commercial information services[10].

Using sensors to enable new social and environmental

critical information services, for example, to improve

transport and mobility processes, this case is directed at

providing trafc data and patterns at the national level

MinorityReport

Nichemarket

iCat

PersonalAttention

RoboCop

Business(or government)

Consumer (orcitizen)

Generaluse

Fig. 2. Framework for case studies.

L. Pennings et al. / Technology in Society 32 (2010) 197203200

-

7/23/2019 8_sept_T&S

5/7

with intelligent sensors that enable new information

services relative to transport and travel needs.

We called this category Minority report because it

brings together several different data sources at the

national level. If this could be considered an archetype,

another example would be a national medical pass and

ID card.

4.3. Case #3: intelligent sensors enable mobile marketingda supermarket

In a retail store such as a supermarket, intelligent

sensors could enable mobile marketing applications to

facilitate communication between producers and

consumers. The supermarket selected for our case study is

already using information and communication technology

(ICT) applications such as narrowcasting and self-scanning.

In addition, management has many ideas about new

applications to communicate product-related information,

for example, to a consumers mobile telephone, but there is

not yet a clear business model. According to the manage-

ment, this will meet the increasing need for product

information on allergies (e.g., gluten or lactose allergies).

Given the increasing cultural diversity of the population

and the growing interest in health and wellness, more

people are seeking information about product ingredients.

A personal telephone could be a more effective alternative

channel than narrowcasting. Another argument could be

the funelement of in-store communication.

Using sensors in mobile commerce to facilitate commu-

nication between producers and consumers, we studied an

innovative supermarket chain in the Netherlands, which

had ideas and plans to use mobile devices to provide

product information, personalised commercials, or on-the-

spot offers in-store. Based on a long customised list of

questions, we constructed a limited questionnaire for

a survey on mobile marketing carried out in a supermarket.

People were invited to answerquestions for about 10 minin

a side room and were rewarded with a free shopping

voucher worth ten euros.

We called this category Personal Attention because of

the mass customisation characteristic of this type of

application, such as marketing for a wide public. If this

could be considered an archetype, other examples would

be personalised trafc information provided by navigation

devices, or information about parking or train times via

mobile phone.

4.4. Case #4: intelligent sensors in living and careda housing

facility for senior citizens

Using sensors in the wide area of applications to living

and care settings (such as for people with health problems,

the disabled, or elderly), we studied a Dutch project where

new services were implemented in a central housing

facility for senior citizens. The complex of 180 apartments,

with approximately 250 occupants, was built in the 1970s.

The building is well-maintained and has many facilities.

The owners association formulated a vision of the future

for two to three years forward. They identied the need

for a basic ICT infrastructure to facilitate telemedicine

applications and home automation (also called domotics) of

household appliances and features in residential dwellings.

The plan provides for integrating several services such as

re call centres, video communication, and a security

system for the building and for individual occupants.

We called this category iCat because of its orientation

and focus on personal preferences and services adapted to

individuals or small groups to improve quality and make

intelligent use of sensors. If this could be considered an

archetype, other examples would be individual health-

monitoring applications and personalised e-shopping

tools.

Table 1summarises some of the research questions and

ndings for each category.

5. The general model applied to the case studies

In general, ICT applications that support the basic

requirements of human communication, such as a level of

security, feeling part of a community, or supporting

personal benets (i.e., whats in it for me?) are likely to be

adopted fairly readily.

On a generic level, we analysed various elements that

inuence these new sensor applications. By analysing the

different elements that comprise the general model,

specic adoption issues were identied for each of the four

different categories.

On a specic level, if we look at the size of use or of the

user group, uniformity within the model in terms of char-

acteristics will be very high on the left-hand side of the

model (Fig. 2), while the diversity within the model will be

high on the right-hand side in our case-study framework.

5.1. The Preconditionsbuilding block in the case studies

The micro individual approach matches well with the

Preconditions building block. In both the Personal

Attention case (mobile marketing) and the iCat case

(service apartments for senior citizens), personal charac-

teristics are most relevant. In the other two cases, there is

very little freedom of choice.

In the mobile marketing research in a supermarket, we

found that the consumers age, i.e., being a digital native or

computer illiterate is very relevant as an adoption criterion

for new sensor applications. This also applies to thegadget

gapddifferences in the numbers and types of devices in

each generation. Other relevant characteristics we found

are the level of knowledge concerning new sensor tech-

nology and individuals learning capabilities in terms of

handling new applications.

5.2. The Trustbuilding block in the case studies

The macro societal approach matches, in particular, with

the building block Trust. This was the case for IJkdijk (Robo-

Cop) and the National Data Warehouse (Minority Report).

In the IJkdijk case we concluded that new technology

shouldrst prove its added value and reliability in order to

be accepted.

In the National Data Warehouse case we concluded that

clear arrangements are required in order to provide sensor

L. Pennings et al. / Technology in Society 32 (2010) 197203 201

-

7/23/2019 8_sept_T&S

6/7

information. Also, because sensor data needs to be reliable,

this should be veried. The same applies to ensuring

availability.

In the mobile marketing case, the fact that the integrity

and reliability of information cannot always be guaranteed

must be taken into account and will be an important

precondition for success. It is important to payconsiderable

attention to communication that involves privacy andsecurity issues; this communication should take the form of

safety procedures, codes, and blocks and privacy protection.

In the case of the service apartments we found the

privacy aspects to be particularly important. Peer inuence

also turned out to be an important issue; initiators are

preferably known members of the group with high

credibility.

5.3. The Acceptancebuilding block in the case studies

Based on the mobile marketing case, we concluded that

there are basic requirements for adopting a product or

service: comfort and ease of use (save time and money),

matching the users needs, social contact and acceptance

in peer groups, and universal use of the devices (not

a new device for each different service). The basic

requirements concerning use of the service are safety and

privacy (of personal preferences and numbers/codes, and

procedures when these are lost), reliability (does the

service function as promised), and usability (simple user

interface, also for disabled users).In the mobile marketing case we found that when

launching a new sensor application it is important to pay

extra attention to privacy measures and prevention of

mistrust (e.g., a trial period to resolve problems, beta

versions for innovators and early adopters in pilots with

support), and pricing issues.

6. Conclusions

People arending that they must cope with increasingly

sophisticated ICT technologies and applications. We expect

ICT to provide solutions for improving data exchange and

access to information, and make processes more effective.

Table 1

Research questions and ndings.

Category Example research questions: Specic characteristics of this category:

IJkdijk

RoboCop

How do the companies involved in

IJkdijk cooperate?

How does the staff responsible for

the dikes experience the taking-over

of tasks, and to what extent do they

trust the data? Questions regarding the integrity of

the sensors (correctness of measured values)

and the integrity of the software and hardware used.

What communication protocols and procedures

are in place?

The focus and aim of (large-scale) implementation

is to improve quality (also safety, where relevant)

and, indirectly, to reduce costs

The applied sensors and their integration is often

at research level.

Users are not familiar with the new sensors. The freedom of choice for users is limited (use of

the sensor system is obligatory).

National Data

Warehouse

Minority Report

How to guarantee that trafc data cannot be

traced back to (the behaviour of) individual users.

NDWs architecture seems to have a single-point-

of-failure. How can the permanent availability of

the system be ensured?

The wide diversity of incoming sensor

information (ows).

Many parties are involved, either as suppliers

or on the demand side.

The various supply organisations entered

into agreements about the quality of the information.

The interfaces need to be protected against misuse.

The overall central party has a coordinating role

with a national, economic interest.

The technologies and implementation are not

mature or proven.

The end user as a consumer is less involved.

Mobile marketing in

supermarket

Personal Attention

In what ways do people use their mobile

phones in supermarkets?

In what kinds of mobile marketing are

customers interested?

What kind of opportunities will mobile

marketing applications provide for supermarkets

in the short and longer term?

Do parties involved in the logistics chain cooperate

with each other?

What will be thenancial drivers of this case?

The sensors are used to facilitate convenience

for end users and to promote products or services

In order to offer users a personalised approach,

personal data is registered, which may compromise

privacy rights.

The initiating central party has a direct commercial

interest.

Thesensors in these applications are widely used.

Marketing is connected to nancial benets, which

increases the risk of fraud.

Service apartment for

senior citizens

iCat

What perceptions do people have regarding sensor

applications in care settings?

Do occupants perceive services in and around theirhomes as luxuries, necessities, or patronising? Why?

Are issues such as experience, generation gaps, and

cultural factors of any relevance?

Who are early adapters of new services (and why)?

How do they inuence other groups?

The target group is relatively small.

The sensors used are state-of-the-art.

The central implementing party has a directcommercial interest (new services generate

additional turnover).

Users often have to be convinced to participate.

Relatively limited risk of fraud and/or misuse.

L. Pennings et al. / Technology in Society 32 (2010) 197203202

-

7/23/2019 8_sept_T&S

7/7

We believe that in the future ICT in general and sensor

networks in particular will have a signicant impact on

society in areas such as care, security, and commerce.

Sensors create richer communication, including context-

aware information. There is much potential for sensor

networks in several sectors.

The success of an intelligent sensor environment is

mainly determined by the extent to which it is adopted by

users. It is not yet clear how technological innovations will

be designed, implemented, and adopted. Furthermore, the

speed of innovation and adoption is difcult to estimate.

To understand how the adoption process works and

when it is likely to be successful, we developed a general

adoption model and applied it to each of the four identied

categories of sensor applications. It turns out that each

specic type of intelligent sensor environment, in addition

to general adoption, has its own adoption issues.

References

[1] Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and useracceptance. MIS Quarterly 1989;13(3):31940.[2] Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD. User acceptance of

information technology: towards a unied view. MIS Quarterly2003;27(3):42578.

[3] Cho V. A study of the roles of trusts and risks in information-oriented online legal services using an integrated model. Informa-tion and Management 2006;43(4):50220.

[4] Schot J, Rip A. The past and future of constructive technology assess-ment. Technology Forecasting and Social Change 1996;54:25168.

[5] Silverstone R. Domesticating domestication: reections on the life ofa concept. In: Berker T, Hartmann M, Punie M, Ward KJ, editors.Domestication of media and technology. London: Open UniversityPress; 2006. p. 22948.

[6] Silverstone R, Hirsch E, Morley D. Information and communicationtechnologies and the moral economy of the household. In:Silverstone R, Hirsch D, editors. Consuming technologies: Media and

Information in Domestic Spaces. London: Routledge; 1992. p. 15

31.[7] Zhao S. Theoretical review of technology mediated communication:Inuences on social structure. Centre for Mobile Communication

Studies (CMCS) Working Paper. Princeton, NJ: Rutgers StateUniversity; 2005. pp. 120.

[8] Rogers E. Diffusion of innovations. New York: Free Press; 1962.[9] IJkdijk website. For more information, see:.

[10] National Data Warehouse website. For more information, see:.

Annemieke de Korteis a researcher and consultant in the Future Scan-ning team of TNO Information and Communication Technology. Shegraduated from the Faculty of Social Sciences at Erasmus University Rot-terdam, with a degree in Sociology of Labour and Technology. Currentlyher work focuses on social trends and their impact on the future use ofinformation and communication technology. She has conducted severalstudies concerning telecommunications, care, education, energy, publicadministration, media, mobility, and safety. These are presented inpublications containing images of the future in concrete communicationcontexts. They aim to be a source of inspiration, enabling organisations tovisualise the future and translate visions into strategies, as a basis fordeveloping new product and service concepts.

Thijs Veugenis a senior expert in the eld of information security. WithinTNO Information and Communication Technology he is responsible forthe strategic knowledge development of the security group. He hasa broad network of academic contacts and develops large projects forbuilding up and extending the strategic information security subjects. Hehas MSc degrees in both Mathematics and Computer Science from Eind-

hoven University of Technology, both with distinction. He graduated incryptography from the Centre for Mathematics and Computer Science in1991. He has a PhD in information theory from Eindhoven University ofTechnology. From 1996 to 1999 he worked as a scientic software engi-neer at Statistics Netherlands. In 1999 he joined TNO in the area ofinformation security. In 2008 he also started as a part-time researcher atthe Multimedia Signal Processing group of Delft University of Technology.

Leo Pennings was a senior researcher and consultant with TNO Infor-mation and Communication Technology, with a background in MolecularBiology (M.Sc. Biochemistry) and Communication (M.Sc. in Communica-tion and Innovation) and Education (B.A. in Education). Within TNOsdepartment of ICT & Policy he was responsible for strategic and policystudies relating to innovations in the information market and issuesrelating to knowledge management, business intelligence and acceptanceand adoption by users of new technology. He participated in variousEuropean projects. Earlier assignments were an EU study on expeditingadoption of e-working collaborative environments, and an EU study onemerging issues, challenges, and policy options for RFID technologies.

L. Pennings et al. / Technology in Society 32 (2010) 197203 203

http://www.ijkdijk.nl/http://www.nationaldatawarehouse.nl/http://www.nationaldatawarehouse.nl/http://www.ijkdijk.nl/