5-20-16 -- Joint Reply Six LASD Defendants -- Appeal

-

Upload

lisa-bartley -

Category

Documents

-

view

66 -

download

0

description

Transcript of 5-20-16 -- Joint Reply Six LASD Defendants -- Appeal

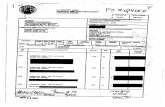

Selected docket entries for case 14−50440

Generated: 05/20/2016 18:05:12

Filed Document Description Page Docket Text

05/20/201692 Main Document 2 Submitted (ECF) Reply Brief for review. Submitted byAppellant Gerard Smith in 14−50440, Appellant MaricelaLong in 14−50441, Appellant Gregory Thompson in14−50442, Appellant Mickey Manzo in 14−50446,Appellant Scott Craig in 14−50449, Appellant StephenLeavins in 14−50455. Date of service: 05/20/2016.[9986030] [14−50440, 14−50441, 14−50442, 14−50446,14−50449, 14−50455] (Genego, William)

(1 of 97)

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellee, v.

GERARD SMITH, Defendant-Appellant.

Case No. 14-50440

D.C. No. 2:13-cr-00819-PA-3 (C.D. Cal., Los Angeles)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellee, v.

MARICELA LONG, Defendant-Appellant.

Case No. 14-50441

D.C. No. 2:13-cr-00819-PA-7 (C.D. Cal., Los Angeles)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellee, v.

GREGORY THOMPSON, Defendant-Appellant.

Case No. 14-50442

D.C. No. 2:13-cr-00819-PA-1 (C.D. Cal., Los Angeles)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellee, v.

MICKEY MANZO, Defendant-Appellant.

Case No. 14-50446

D.C. No. 2:13-cr-00819-PA-4 (C.D. Cal., Los Angeles)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellee, v.

SCOTT CRAIG, Defendant-Appellant.

Case No. 14-50449

D.C. No. 2:13-cr-00819-PA-6 (C.D. Cal., Los Angeles)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellee,

v. STEPHEN LEAVINS, Defendant-Appellant.

Case No. 14-50455

D.C. No. 2:13-cr-00819-PA-2 (C.D. Cal., Los Angeles)

________________________________

Joint Reply Brief of Defendants-Appellants ________________________________

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 1 of 96(2 of 97)

HILARY POTASHNER Federal Public Defender GAIL IVENS ELIZABETH RICHARDSON-ROYER Deputy Federal Public Defenders 321 East 2nd Street Los Angeles, CA 90012-4202 Telephone 213-894-5092 Attorneys for Maricela Long

WILLIAM J. GENEGO Law Office of William Genego 2115 Main Street Santa Monica, California 90405 Telephone: 310-399-3259 Counsel for Gerard Smith

KEVIN BARRY MCDERMOTT 8001 Irvine Center Drive, Suite 1420 Irvine, California 92618 Telephone: 949-596-0102

Counsel for Gregory Thompson

MATTHEW J. LOMBARD Law Offices of Matthew J. Lombard 2115 Main Street Santa Monica, California 90405 Telephone: 310-399-3259

Counsel for Mickey Manzo

KAREN L. LANDAU Law Offices of Karen L. Landau 2626 Harrison Street Oakland, CA 94612 Telephone: 510-839-9230 Attorney for Scott Craig

TODD W. BURNS Burns & Cohan, Attorneys at Law 1350 Columbia Street, Suite 600 San Diego, California 92101 Telephone: 619-236-0244 Attorneys for Stephen Leavins

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 2 of 96(3 of 97)

i

Table of Contents

Table of Authorities ................................................................................................................ iv

Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1

I. The Instructional Errors Denied Defendants The Right to Have the Jury Consider Their Mens Rea Defenses of Reasonable Reliance On Apparent Authority and Good Faith .......................................................................................... 2

A. The Court Erred In Denying a Public Authority Mens Rea Instruction and In Giving an Erroneous Good Faith Instruction. ....... 2

1. It Was Error to Deny a Mens Rea Public Authority Instruction ... 2

2. The Court’s Altered Good Faith Instruction Was Incorrect ........... 8

B. Reversal Is Separately Required Because the Court’s Instructions Erroneously Advised the Jury that Local Officers Could Not Investigate the Introduction of Contraband into MCJ .......................... 12

C. The Improper Dual Purpose Instruction Undermined Defendants’ Right to Have the Jury Consider Their Mens Rea Defense ................. 16

II. The Jury Instructions Allowed Conviction on an Invalid Legal Theory ... 18

A. Relevant Background ....................................................................................... 19

B. Standard of Review ........................................................................................... 21

C. The Obstruction Counts of Conviction Should Be Vacated Because the Government Pressed An Invalid Theory. ........................................... 22

D. The Court Erred in Denying Defendants’ Requested Instructions that the Government Must Show that They Intended to Obstruct a Grand Jury Proceeding, Not Just an FBI Investigation. ...................................... 25

E. The Court Erred in Instructing the Jury that It Could Convict If It Found that Defendants Intended to Obstruct “the Grand Jury Investigation,” Rather that “a Grand Jury Proceeding” ........................ 34

F. The Court Erred in Failing to Instruct the Jury that Defendants Had to Know Their Conduct Was Likely to Influence a Grand Jury Proceeding ........................................................................................................... 36

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 3 of 96(4 of 97)

ii

III. The Court Erred In Excluding the Testimony of Paul Yoshinaga, a Key Defense Witness………………………………………………………………………………………….. 37

A. Yoshinaga’s Testimony was Relevant .......................................................... 39

B. Yoshingaga’s Testimony Was Not Excludable Under Rule 403 ......... 42

C. The Error Was Not Harmless, and It Infringed Leavins’s Constitutional Right to Present a Defense ................................................. 44

D. The Government Improperly Capitalized on the Erroneous Preclusion Order ................................................................................................ 47

IV. The District Court’s Many Erroneous Evidentiary Rulings, Alone and Cumulatively, Resulted in a Denial of the Right to Present a Complete Defense ........................................................................................................................... 50

A. The Erroneous Evidentiary Rulings Individually Require Reversal. 50

1. The Court Improperly Excluded Evidence Rebutting the Contention that Brown Could Have Been Safely Held at MCJ. .. 50

2. The Court Improperly Admitted Evidence Concerning Specific Instances of Inmate Abuse. ..................................................................... 52

3. The Court Improperly Limited Cross-Examination of Pearson Regarding the Writ. ................................................................................... 55

4. The Court Erroneously Precluded the Defense From Cross-examining LASD Sergeant Martinez About a Legal Opinion. .... 57

5. The Court Improperly Refused to Permit the Defense to Question AUSA Middleton as an Adverse Witness ........................................... 59

6. The Court Erroneously Excluded Evidence of Baca’s Attitude and the Specific Orders He Gave in Late September ..................... 60

7. The Court Made Other Erroneous Evidentiary Rulings................ 62

B. The Cumulative Effect of the Errors Require Reversal ......................... 63

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 4 of 96(5 of 97)

iii

V. The Court’s Dismissal of Juror Five Violated Defendants’ Sixth Amendment Jury Trial Right .................................................................................. 65

A. Standard of Review and Applicable Legal Test ....................................... 66

B. There Is a Reasonable Possibility the Juror’s Initial Request to Be Excused Stemmed From a Conflict Amongst the Jurors ...................... 68

VI. The Defendants Did Not Have Fair Notice that Their Actions Violated Federal Criminal Law ................................................................................................ 73

VII. The Convictions Rest On a Legally Mistaken Definition of “Corruptly” .. 75

VIII. The Case Should Be Reassigned to a Different Judge on Remand. ............ 76

Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 77

Addendum………………………….………………………………………………………………………………..... 78

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 5 of 96(6 of 97)

iv

Table of Authorities

Federal Cases

Alcala v. Woodford, 334 F.3d 862 (9th Cir. 1993) ........................................................................................... 44

Armstrong v. Exceptional Child Ctr., Inc., 135 S. Ct. 1378 (2015)....................................................................................................... 15

Bisno v. United States, 299 F.2d 711 (9th Cir. 1962) ........................................................................................... 41

Chapman v. California, 386 U.S. 18 (1967) .............................................................................................................. 64

Clifton v. Cox, 549 F.2d 722 (9th Cir. 1977) ........................................................................................... 15

Comm. of Kentucky v. Long, 837 F.2d 727 (6th Cir. 1988) ........................................................................................... 15

Idaho v. Horiuchi, 253 F.3d 359 (9th Cir.) ..................................................................................................... 15

In re Neagle, 135 U.S. 1 (1890) ................................................................................................................ 15

New York v. Tanella, 374 F.3d 141 (2d Cir. 2004) ............................................................................................ 15

North Carolina v. Cisneros, 947 F.2d 1135 (4th Cir. 1991) ........................................................................................ 15

Ohio v. Thomas, 173 U.S. 276 (1899) .................................................................................................... 14, 15

Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232 (1974) ........................................................................................................... 74

United States ex rel. Drury v. Lewis, 200 U.S. 1 (1906) ................................................................................................................ 15

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 6 of 96(7 of 97)

v

United States v. Aguilar, 515 U.S. 593 (1995) .................................................................................................. passim

United States v. Barker, 546 F.2d 940 (D.C. Cir. 1976) ..................................................................................... 7, 8

United States v. Beard, 161 F.3d 1190 (9th Cir. 1998) ........................................................................................ 73

United States v. Boulware, 384 F.3d 794 (9th Cir. 2004) ........................................................................................... 64

United States v. Brown, 562 F.2d 1144 (9th Cir. 1977) ................................................................................. 11, 20

United States v. Bryant, 461 F.2d 912 (6th Cir. 1972) ........................................................................................... 59

United States v. Bush, 626 F.3d 527 (9th Cir. 2010) ........................................................................................... 41

United States v. Cannon, 475 F.3d 1013 (8th Cir. 2007) ........................................................................................ 73

United States v. Christensen, 801 F.3d 970 (9th Cir. 2015) ............................................................................. 67, 69, 72

United States v. Custer Channel Wing Corp., 376 F.2d 675 (4th Cir. 1967) .................................................................................... 41, 43

United States v. Doe, 710 F.3d 1134 (9th Cir. 2013)................................................................................. passim

United States v. Egan, 860 F.2d 904 (9th Cir. 1988) ........................................................................................... 22

United States v. Fierros, 692 F.2d 1291 (9th Cir. 1982) ............................................................................ 5, 6, 7, 8

United States v. Fulbright, 105 F.3d 443 (9th Cir. 1997) .................................................................................... 23, 36

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 7 of 96(8 of 97)

vi

United States v. Hardy, 289 F.3d 608 (9th Cir. 2002) .................................................................................... 53, 60

United States v. Hopper, 177 F.3d 824 (9th Cir. 1999) ...................................................................... 27, 29, 30, 31

United States v. Keys, 133 F.3d 1282 (9th Cir. 1998) ........................................................................................ 12

United States v. Lopez–Alvarez, 970 F.2d 583 (9th Cir. 1992) ........................................................................................... 64

United States v. Mkhsian, 5 F.3d 1306 (9th Cir. 1993) ............................................................................................. 12

United States v. Moran, 493 F.3d 1002 (9th Cir. 2007) ........................................................................................ 44

United States v. Orm Hieng, 679 F.3d 1131 (9th Cir. 2012) ................................................................................. 11, 47

United States v. Pablo Varela-Rivera, 279 F.3d 1174 (9th Cir. 2002) ........................................................................................ 54

United States v. Perdomo-Espana, 522 F.3d 983 (9th Cir. 2008) ............................................................................................. 2

United States v. Perez, 116 F.3d 840 (9th Cir. 1997) ........................................................................................... 37

United States v. Petersen, 513 F.2d 1133 (9th Cir. 1975) ............................................................................ 3, 5, 7, 8

United States v. Rivera-Corona, 618 F.3d 976 (9th Cir. 2010) .................................................................................... 42, 54

United States v. Smith-Baltiher, 424 F.3d 913 (9th Cir. 2005) ............................................................................... 3, 5, 6, 8

United States v. Stever, 603 F.3d 747 (9th Cir. 2010) ........................................................................................... 64

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 8 of 96(9 of 97)

vii

United States v. Symington, 195 F.3d 1080 (9th Cir. 1999) .......................................................................... 67, 68, 69

United States v. Thomas, 116 F.3d 606 (2d Cir. 1997) ............................................................................................ 72

United States v. Thomas, 32 F.3d 418 (9th Cir. 1994) ............................................................................................. 48

United States v. Thompson, 37 F.3d 450 (9th Cir. 1994) ............................................................................................. 41

United States v. Triumph Capital Group, Inc., 544 F.3d 149 (2d Cir. 2008) ..................................................................................... 28, 37

United States v. Velasquez-Bosque, 601 F.3d 955 (9th Cir. 2010) ........................................................................................... 63

United States v. Williamson, 439 F.3d 1125 (9th Cir. 2006) ........................................................................................ 63

Williams v. Cavazos, 646 F.3d 626 (9th Cir. 2011) ........................................................................................... 67

Federal Statutes

18 U.S.C. § 1503 ............................................................................................................. passim

28 U.S.C. § 1442(a) .................................................................................................... 15, 73, 74

Federal Rules

Fed. R. Crim. P. 23 ........................................................................................................... 66, 67

Fed. R. Crim. P. 30 .................................................................................................................. 12

Fed. R. Evid. 403 ................................................................................................ 39, 43, 54, 61

Fed. R. Evid. 611(c)(2) ............................................................................................................ 59

Other Authorities

Seth P. Waxman & Trevor W. Morrison, What Kind of Immunity? Federal Officers, State Criminal Law and the Supremacy Clause, 11 Yale L.J. 2195 (2003) .................................................................................................... 74

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 9 of 96(10 of 97)

1

INTRODUCTION

The government’s 65 page statement of facts is an apparent attempt to

convince the Court the evidence of guilt was overwhelming, and any errors thus

harmless. But, as suggested by the jury’s six days of deliberations, the evidence

was not overwhelming. Clerk’s Record: 431, 434, 435, 436, 465, 467.

In attempting to make it appear so, the government editorializes the facts.

The government’s statement of facts makes conclusory assertions as to

Defendants’ purported intent that are unabashedly argumentative; attributes

roles and actions to individual Defendants they did not have; assigns arguments

to Defendants they did not make; fails to acknowledge evidence that contradicts

its assertions; and makes erroneous statements of fact. Collectively they

purposefully paint a picture of a carefully designed operation in which

Defendants played an integral and decision-making role, in sharp contrast to

what the record shows was, in reality, a rapidly unfolding series of events fueled

by a lack of trust between the Sheriff and the FBI.

The number of overstatements and misstatements in the government’s

statement of facts precludes detailing them all, but their significance requires

that they not be ignored. Defendants have catalogued examples of such instances

in an addendum to this reply. See Addendum, infra at 77-86.

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 10 of 96(11 of 97)

2

REPLY ARGUMENT

I. The Instructional Errors Denied Defendants the Right to Have the Jury

Consider Their Mens Rea Defenses of Reasonable Reliance On Apparent

Authority and Good Faith.

Four separate instructional errors prevented the jury from fairly

considering and accurately determining whether the government proved the

Defendants acted with the mens rea required by the obstruction of justice counts

and corresponding conspiracy charge. Defendants’ Joint Opening Brief (“JOB”)

38-56. The government fails to rebut the showing of error as to any of them.

A. The Court Erred In Denying a Public Authority Mens Rea

Instruction and In Giving an Erroneous Good Faith Instruction.

1. It Was Error to Deny a Mens Rea Public Authority Instruction.

Defendants’ requested instruction stated that an officer who acts pursuant

to orders of superiors that the officer reasonably believes are lawful, lacks the

mens rea required for conviction. JOB 41. The government concedes that

Defendants were entitled to the instruction if “it ‘has support in the law and

some foundation in the evidence.’” Government’s Answering Brief (“GAB”) 81,

quoting United States v. Perdomo-Espana, 522 F.3d 983, 987 (9th Cir. 2008).

Defendants’ requested instruction had both. JOB 41-45; 1 ER: 70. The

government’s attempt to establish otherwise rests on its contention that a public

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 11 of 96(12 of 97)

3

authority defense may only be used to excuse the commission of a crime, and

thus requires actual authority to commit the charged crime. Since the proposed

instruction did not include such a requirement, the government contends it was

not supported by the law. The government’s arguments fail because the law

recognizes that a public authority defense based on reasonable reliance on

apparent authority may also negate mens rea, meaning no crime was committed,

and there was abundant evidence which supported that defense and the

requested instruction.

a) The Instruction Is Supported By the Law.

Defendants identified decisions of this Court which support the requested

instruction, including United States v. Doe, 710 F.3d 1134, 1146-47 (9th Cir.

2013), which recognizes that for certain offenses, a public authority defense may

negate an element of the crime. Id. at 1146-47; JOB 41-42. Defendants also cited

several decisions which recognized the related principle that a defendant’s

reasonable belief that his or her actions were lawfully authorized, even if

mistaken, may “negate the specific intent required for culpability,” as it fits

within the narrow category of cases where a mistake of fact about the law is a

defense. JOB 39-40, quoting United States v. Smith-Baltiher, 424 F.3d 913, 924-

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 12 of 96(13 of 97)

4

25 (9th Cir. 2005); United States v. Petersen, 513 F.2d 1133, 1134-35 (9th Cir.

1975); see also, United States v. Fierros, 692 F.2d 1291, 1294 (9th Cir. 1982).

The government attempts to distinguish Doe by maintaining it only affects

the burden of proof, and not the elements of a public authority defense. The

government thereby asserts that Defendants’ position that they “acted pursuant

to their superiors’ orders which they reasonably believed were lawful” is

“irrelevant,” as they were not authorized to obstruct justice. GAB 83.

The government’s attempt to limit Doe is proved wrong by the opinion

itself: the elements of a public authority defense “depend[] on both the statute at

issue and the facts of the specific case.” Doe, 705 F.3d at 1147. The statute at

issue here only proscribes acts done with a specific prohibited purpose, as

opposed to the general intent crime in Doe. And the facts established that

Defendants lacked the prohibited mens rea because they were acting pursuant to

what they reasonably believed were lawful orders of their superiors.

Where the defense is used to negate the element of mens rea, it means no

crime was committed, and does not require an agent who can empower someone

to commit an illegal act. Thus, the absence of such a requirement from

Defendants’ proposed instruction does not mean it is not supported by the law.

To the contrary, Doe’s recognition that a public authority defense may negate an

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 13 of 96(14 of 97)

5

element of an offense provides sufficient legal support for the requested

instruction.

The government’s attempt to discredit Defendants’ reliance on Smith-

Baltiher, Fierros and Petersen similarly fails.

The government asserts that the “intent standard is different and simpler”

in Smith-Baltiher than in this case. GAB 85-86. While the facts are different, the

“intent standard” is the same -- attempted illegal reentry is a specific intent crime

requiring one act with a specific purpose prohibited by the statute, entry into the

United States without the consent of the Attorney General (Smith-Baltiher, 424

F.3d at 923), just as a violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1503 is a specific intent crime that

requires one act with the prohibited purpose of obstructing a judicial proceeding.

And just as “a mistake of fact provides a defense to a crime of specific intent

such as attempted illegal reentry,” Smith-Baltiher, 424 F.3d at 924, it provides a

defense to the specific intent crime of obstruction of justice.1

1 The government twice mistakenly attributes a quotation to the Court in Smith-Baltiher to suggest (incorrectly) that the defendant in that case was only permitted to present a reasonable mistake of fact defense because “knowledge of an ‘independently determined legal status [was] one of the operative facts of the crime.’” GAB at 85, quoting Smith-Baltiher, 424 F.3d at 924; see GAB 86 (contrasting this case with Smith-Baltiher by asserting Defendants here “did not

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 14 of 96(15 of 97)

6

The government’s contention that Fierros does not support the requested

instruction because Defendants were not prosecuted under a “complex

regulatory scheme[],” is also wrong. GAB 86. Fierros identified two

circumstances where such a defense is available, and this case, like Petersen, fits

the first circumstance: where the defendant is ignorant of a “condition that is one

of the operative facts of the crime.” Id., 692 F.2d at 1294. In Petersen, the

defendant reasonably believed the person was authorized to sell the property in

question, and in this case, Defendants reasonably believed their superiors’ orders

were lawful.

The government’s only attempt to distinguish Peterson is to assert in a

parenthetical that the Court in Fierros held that Petersen comes within one of

the two categories of cases where “a defense of ignorance of the law is

permitted.” GAB 86. The government presumably includes this assertion to

need knowledge of any ‘independently determined legal status or condition[].’”) quoting Smith-Baltiher, 424 F.3d at 924 (brackets added by government).

The quotation is actually from the Court’s opinion in Fierros, which Smith-Baltiher quoted. Contrary to the government’s suggestion, the quote did not refer to the crime at issue in Smith-Baltiher, attempted illegal entry, but rather it referred to the crime in Petersen, embezzlement or theft of federal property. See Smith-Baltiher, 424 F.3d at 924, quoting Fierros, 692 F.2d at 1294, citing United States v. Petersen, 513 F.2d 1133 (9th Cir. 1975).

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 15 of 96(16 of 97)

7

suggest that Defendants’ reliance on Petersen is misplaced because of the general

rule that ignorance of the law is not a defense. GAB 84-85, citing Fierros, 692

F.2d at 1294. This attempt is meritless because in Fierros, the Court clarified

that Petersen is an example of a case where “the mistake of law is for practical

purposes a mistake of fact.” Fierros, 692 F.2d at 1294.

Importantly, Fierros cited the concurring opinion in United States v.

Barker, 546 F.2d 940, 945-54 (D.C. Cir. 1976), which parallels the circumstances

here – the defendants there were prosecuted for conspiracy to violate civil rights

based on having burglarized a psychiatrist’s office to obtain records regarding

Daniel Ellsberg who was being investigated for leaking the Pentagon Papers. The

defendants maintained they lacked the mens rea required for conviction because

they reasonably relied on the apparent authority conveyed by CIA operative E.

Howard Hunt that their actions were authorized by the government. Id. 546 F.2d

at 945-54 (Wilkey, J., concurring). Barker is the seminal case recognizing that a

reasonable mistake of fact about the law provides a defense in the circumstances

of this case. The support it provides for the requested instruction here is

especially significant, as Fierros cites to Barker, and equates Barker with

Petersen. Further, Smith-Baltiher adopts that portion of the Fierros’s opinion.

Fierros, 692 F.2d at 1294; Smith-Baltiher, 424 F.3d at 924.

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 16 of 96(17 of 97)

8

b) The Instruction Was Supported By the Evidence.

The government does not dispute Defendants’ showing that there was

abundant evidence supporting the requested instruction, i.e., there was testimony

the Defendants’ actions were authorized by their superiors, and that it was

reasonable for Defendants to believe the orders were issued for a lawful purpose.

JOB 43-45.

Instead, the government makes the inapposite argument that it was proper

for the court to deny the instruction because there was no evidence Defendants

were authorized to obstruct justice. GAB 86-87. As the government well knows,

that was never the defense. Defendants repeatedly explained in the district court

and before this Court that their mens rea defense is that they did not obstruct

justice, not that they were authorized to do so. JOB 45. The absence of evidence

that Defendants were authorized to obstruct justice could not possibly justify

denying the instruction.

2. The Court’s Altered Good Faith Instruction Was Incorrect.

The court separately erred when it added a clause to the good faith

instruction that materially altered its meaning. As altered, the instruction

mistakenly allowed the jury to find that an officer who relied in good faith on a

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 17 of 96(18 of 97)

9

superiors’ order that the officer reasonably and objectively believed were lawful

could possess the unlawful intent required for conviction.2

The government does not dispute the premise that an officer who relied in

good faith on superiors’ orders that the officer reasonably and objectively

believed to be lawful could not have the corrupt intent required for conviction.

Nor does the government dispute that the only reason for the court to add the

clause was to change the meaning of the instruction to make it consistent with

the dual-purpose instruction and allow the jury to convict even if it found a

defendant relied in good faith on superiors’ orders. And the government offers

no explanation as to why the court would alter the good faith instruction in this

manner in Defendants’ trial, but not in either of co-defendant Sexton’s two trials,

except to neutralize Defendants’ good faith defense. See JOB 46, 49.

2 The court altered the meaning by adding the following underlined clause to the agreed upon good faith instruction: “Evidence that a defendant relied, in good faith, on the orders the defendant received from the defendants’ superior officers, and that the defendant reasonably and objectively believed those orders to be lawful, is inconsistent with unlawful intent and is evidence you may consider in determining if. . . . a defendant had the required unlawful intent.” JOB 48, quoting ER 1A: 262-63 (emphasis added).

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 18 of 96(19 of 97)

10

Instead, the government responds by misstating Defendants’ claim.3 The

government then argues there was no error because the clause added by the

court was technically “not inaccurate.” GAB 96; Id. 97. It is true that the jury

could consider such evidence, and thus the clause viewed in isolation “was not

inaccurate.” But that argument ignores the substance of the error.

In fact, the government never addresses the substance of the error, other

than indirectly, by suggesting Defendants’ argument depends on “an

overwrought reading of the instruction.” GAB 96. This assertion rests on the

proposition that the court added the clause for no reason, which of course cannot

be true.

The government’s contention that only Leavins preserved objection to the

altered instruction is contradicted by the record. GAB 94. Smith accepted the

instruction as it had been proposed by the defense and government, but as the

3 The government twice represents, incorrectly, that Defendants’ claim is that the court “should have instructed the jury that such reliance ‘provided a complete defense.’” GAB 95, quoting JOB 95; GAB 97. Defendants used the phrase “complete defense” in their opening brief to explain the nature of the error, but never argued or suggested it should have been included in the instruction. Defendants’ argument is that the instruction should have been given as proposed by the parties, and as it was given in both Sexton trials, without the additional clause.

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 19 of 96(20 of 97)

11

government concedes, Smith expressly added that he was preserving the dual-

purpose objection. GAB 94, n.20. This was a reference to the clause added by the

court, as it altered the instruction to make it consistent with the dual-purpose

instruction. ER 1A: 241; JOB 49.

The government’s assertion that the claim is subject to plain error review

as to the remaining Defendants is incorrect, as case law holds that an objection

to an instruction by one defendant preserves it as to other defendants. See

United States v. Brown, 562 F.2d 1144, 1147 n.1 (9th Cir. 1977); see also, United

States v. Orm Hieng, 679 F.3d 1131, 1141 (9th Cir. 2012). Thus, Leavins’

objection preserved the error as to all defendants who did not actively oppose the

objection. Further, the Court should exercise its discretion to consider the error

as to all Defendants, given that the government can show no prejudice in

allowing the claim to be considered on behalf of the remaining Defendants, and

given that it would be particularly unjust to limit relief to Leavins and Smith.4

4 See United States v. Mkhsian, 5 F.3d 1306, 1310, n.2 (9th Cir. 1993) (granting reversal to co-defendant who adopted instructional error argument of co-appellant in his reply brief, where it would not be prejudicial to the government, and because “it would be unjust to reverse” the conviction of one defendant and not the other), overruled on other grounds, United States v. Keys, 133 F.3d 1282 (9th Cir. 1998).

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 20 of 96(21 of 97)

12

Additionally, even if the question is reviewed for plain error, the Defendants are

entitled to relief. The court plainly erred in altering the good faith instruction

and the error affected the Defendants’ substantial rights. Finally, any question

as to whether the claim was preserved should be resolved in favor of the

Defendants, given the trial court’s failure to comply with Fed. R. Crim. P. 30.

JOB 49.

B. Reversal Is Separately Required Because the Court’s Instructions

Erroneously Advised the Jury that Local Officers Could Not

Investigate the Introduction of Contraband into the Jail.

The government makes two arguments in response to Defendants’ claim

that the court erred in instructing the jury that Anthony Brown’s possession of

contraband would not be a violation of specified California Penal Code

provisions if it was directed by the FBI, and that the effect of that erroneous

instruction was to tell the jury that Defendants could do no further investigation

once “they found out that that was an FBI phone. . . .” JOB 51; ER 1A: 112, 113,

257; see also ER 1A: 114-119; 138, 170-71.

The government first argues that it was not “the purpose nor the import of

the instruction” to advise the jury that Defendants could do no further

investigation after the LASD learned it was an FBI phone. GAB 106-07. The

record proves the opposite. The court plainly stated its view of the law that

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 21 of 96(22 of 97)

13

Defendants could not investigate once the LASD learned it was an FBI phone,

and the court made known its intention to instruct the jury accordingly. JOB 51;

ER 1A: 112, 113 (local officers could investigate “up until the time they found

out that that was an FBI phone. . . . Once they found out it was an FBI phone,

ballgame’s over.”); see also ER 1A: 114-119; 138, 170-71, 213-223. The

prosecutor’s rebuttal argument using the court’s own analogy confirms that the

instruction conveyed this point:

When the head of the FBI called Leroy Baca and accepted

[sic] it was an FBI phone, game over. There was nothing more to

do. It was done.

RT 4008 (emphasis added)

If, as the government contends, the court’s concern and purpose was that

the jury not be misled by testimony from Leavins and Craig as to whether there

was possibly a violation of the Penal Code provisions, the court could have

instructed the jury as to the elements of the offenses. There was no need to

instruct the jury that there was no violation if the conduct occurred “at the

direction of the FBI.” ER 1A: 257.

The government’s second argument -- that the court’s instruction was

legally correct, i.e., that “if Brown possessed any cellular telephone at the

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 22 of 96(23 of 97)

14

direction of the FBI, no violation of California Penal Codes would have

occurred” – is also wrong. GAB 108.

The government relies on Ohio v. Thomas, 173 U.S. 276, 283 (1899),

stating that federal officers “are not subject to arrest . . . under the laws of the

state in which their duties are performed.” GAB 109. Thomas is not only

distinguishable on the facts,5 but the quoted statement is not good law; it is

contradicted by a long history of cases dating back more than 100 years in which

federal agents were actually prosecuted,6 and cannot be reconciled with

5 Thomas involved the application of a state law to a federal soldier’s home, and the home was “a federal creation, and [was] under the direct and sole jurisdiction of congress.” Thomas, 173 U.S. at 281. Given that the home was subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the federal government, “the police power of the state [had] no application” to its operation. Id., 173 U.S. at 283.

6 See, e.g., In re Neagle, 135 U.S. 1 (1890) (Deputy U.S. Marshal prosecuted for murder); United States ex rel. Drury v. Lewis, 200 U.S. 1, 2 (1906) (enlisted officer prosecuted for shooting suspect to prevent him from escaping); see New York v. Tanella, 374 F.3d 141 (2d Cir. 2004) (DEA agent prosecuted by state for killing drug dealer after high-speed chase); Comm. of Kentucky v. Long, 837 F.2d 727 (6th Cir. 1988) (FBI agent prosecuted by state after having approved informant’s commission of burglaries); Clifton v. Cox, 549 F.2d 722 (9th Cir. 1977) (federal agent prosecuted for shooting suspect who fled in the course execution of a search warrant).

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 23 of 96(24 of 97)

15

Congress’ subsequent passage of 28 U.S.C. § 1442(a).7 Thomas provides no

support for the court’s instruction.8

The government also seeks to defend the instruction by equating

possession “at the directions of the FBI” with authorization under the Penal

Code sections. Thus, the government asserts that regardless of whether

authorization is an affirmative defense, or if the possession of contraband must

“be unauthorized for a crime to occur,” the “instruction correctly stated that ‘no

violation of these’ codes occurred if ‘Brown possessed any contraband . . . at the

direction of the FBI.’” GAB 109-110, quoting ER 257 (ellipsis added by

government). But a federal agent is not among the people who are empowered to

7 Section 1442(a) allows federal agents charged with violations of state law to remove the case to federal court and thus necessarily assumes that federal agents can, and sometimes are, prosecuted for violations of state law for acts engaged in while carrying out their duties as federal agents. See Idaho v. Horiuchi, 253 F.3d 359, 376-77 (9th Cir.) (en banc), vacated as moot, 266 F.3d 979 (9th Cir. 2001).

8 Contrary to the government’s apparent belief, Defendants did not cite Armstrong v. Exceptional Child Ctr., Inc., 135 S. Ct. 1378, 1383 (2015) as support for the proposition that federal agents can be arrested. GAB 109, n. 26. Armstrong is only relevant in that it establishes that the Supremacy Clause does not provide federal agents with the power to authorize violations of state law. JOB 53.

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 24 of 96(25 of 97)

16

grant authorization under the Penal Code sections. The government never

identifies the source of a federal agent’s supposed power to authorize an inmate

in a county jail to possess contraband under the Penal Code, because there is

none. JOB 53-54.

The government’s suggestion that the instruction was not prejudicial

because the court instructed the jury that local officers “have the right to

investigate potential violations of state law,” including “potential violations of

state law by federal agents,” ignores that the instruction as a whole wrongly

advised the jury that Defendants could do no lawful investigation after the LASD

learned it was an FBI phone. JOB 54; pp. 12-13, supra. Further, while the court’s

instruction did not expressly “foreclose defendants’ arguments regarding their

intent” (GAB 107), that was its practical effect. It foreclosed the jury from

accepting Defendants’ argument that their intent was to lawfully investigate,

because according to the court’s instruction, there was no potential violation of

state law, and if there was no potential state law violation, local officers could not

investigate. JOB 54, ER 1A: 256.

C. The Improper Dual-Purpose Instruction Undermined Defendants’

Right to Have the Jury Consider Their Mens Rea Defense.

The parties’ disagreement as to the fourth instructional error impacting

the mens rea and good faith defense – the court’s dual-purpose instruction --

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 25 of 96(26 of 97)

17

turns on whether Defendants could simultaneously act in good faith for the

purpose of following orders they reasonably and objectively believed were lawful,

and do so for the unlawful purpose of obstructing justice. JOB 55-56; GAB 88-91.

The government attempts to rebut Defendants’ contention that these

purposes are mutually exclusive by analogizing the payment of money for the

mixed motive of friendship and a desire to bribe, and taking an action for two

unlawful purposes, to steal money from clients and evade taxes. GAB 90. The

government’s analogies and argument fail because Defendants here did not

contend they were acting for a purpose that was lawful, but rather that their very

purpose was to act lawfully, in compliance with their obligation to obey

superiors’ orders. Government’s Excerpts of Record (“GER”) 1552 (LASD,

“Obedience to Laws, Regulations and Orders”). Defendants did not maintain

they had a “desire” to follow a lawful order as the government puts it, which

wrongly suggests it was a voluntary choice, but rather that they had an obligation

to carry out all lawful orders and thus their purpose was to act in compliance

with the law.

The government suggests that even if these purposes were mutually

exclusive, there was no error because Defendants “also claimed, regardless of

orders, that” their actions were motivated by other reasons, such as keeping

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 26 of 96(27 of 97)

18

Brown safe. GAB 90 (emphasis added). But Defendants maintained they took the

actions described by the government because of the orders, not regardless of

them.

Finally, the government’s suggestion that there was no prejudice because if

the purposes were mutually exclusive “then the instruction would have no effect

at all” (GAB 90), ignores that the instruction endorsed the proposition that that

Defendants could act in good faith and simultaneously have the mens rea

required for conviction. The dual-purpose instruction, like the court’s alteration

of the good faith instruction, allowed the government to advance the erroneous

argument that even if Defendants were carrying out what they believed was a

legitimate investigation, they could still be guilty.

II. The Jury Instructions Allowed Conviction on an Invalid Legal Theory

The government repeatedly led the jurors to believe that they could

convict if they found Defendants intended to obstruct the FBI (as opposed to a

grand jury proceeding), and the district court made three instructional errors

that allowed conviction on that invalid theory. Though the four issues raised in

this context are closely related, the government treats them as independent,

which allows it to (1) make meritless waiver/forfeiture arguments, (2) press an

incorrect abuse of discretion standard of review, and (3) ignore the cumulative

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 27 of 96(28 of 97)

19

effect of the instructional errors. Before turning to the government’s arguments,

Defendants summarize key aspects of the relevant background.

A. Relevant Background

The parties submitted disputed proposed jury instructions a month before

trial. Even at that point, it was apparent to defense counsel that the government’s

case would be based largely on the theory that Defendants intended to obstruct

the FBI, rather than a grand jury proceeding. To prevent the jury from

convicting on that invalid theory, defense counsel proposed two similar

instructions that told the jury that the government had to prove Defendants

“acted with the intent to obstruct a grand jury investigation, and not just an FBI

or US Attorney’s Office investigation.” ER 1A: 40; see also ER 1A: 37.9

The government objected to both instructions, claiming that they “would

exclude a jury from finding obstruction even if the federal agents were acting as

arms of the grand jury.” ER 1A: 38, 41. Defense counsel responded that “[e]ven if

it were true that interference with an agent who was acting as an arm of the

9 The instructions requested by Leavins, Smith and Manzo preserved the claim as to Thompson, Craig, and Long, as did their objections to the court’s use of the phrase “grand jury investigation. See Brown, 562 F.2d at 1147, n. 1; ER 1A: 123-128.

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 28 of 96(29 of 97)

20

grand jury could be the basis for a conviction,” that would not obviate the need

for the requested instructions, but would instead require “additional

instruction(s) telling that to the jury and defining what the government must

prove for an agent to be deemed an arm of the grand jury.” ER 1A: 39.

At the first jury instruction conference during the fifth week of trial,

defense counsel said the instructions discussed above were necessary because

“there’s been a lot of mention during the trial of obstructing the FBI . . . .” ER

1A: 131. Indeed, FBI Agent Dahle bluntly testified that Defendants “were on

notice that it was an FBI investigation. They should not have obstructed it.” ER

2: 758. Without explanation, the court declined to give the requested

instructions.

Defense counsel also argued that the Ninth Circuit model instruction on

§ 1503(a)’s elements was not sufficient because the meaning of obstructing the

“due administration of justice needs to be . . . defined . . .” ER 1A: 123. Defense

counsel pointed out that it would be problematic to define that phrase by

referring to an intent to obstruct a “grand jury investigation,” when in fact the

government must show that the defendant intended to obstruct a “grand jury

proceeding.” Id. The government responded, “I don’t think there’s a significance

between grand jury proceeding and grand jury investigation. I think that’s what

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 29 of 96(30 of 97)

21

grand juries do, they investigate.” Id. Defense counsel replied that “the offense is

obstruction of a grand jury proceeding, not an investigation,” and “if you don’t

restrict it to a proceeding and just have to do with an investigation, it becomes

much more amorphous and you run into an Aguilar problem.” Id. 124, 126. By

“an Aguilar problem,” defense counsel was referring to the jurors being misled

into believing that they could convict based on finding that Defendants intended

to obstruct the FBI. See United States v. Aguilar, 515 U.S. 593 (1995).

The next day, the court came back to this issue and said that it would give

the model jury instruction but would replace the generic references to

obstructing justice with references to a “grand jury investigation.” ER 1A: 160.

Defense counsel maintained their objection, ER 1A: 224, but the court overruled

it and instructed the jurors that they had to find:

First, the defendant influenced obstructed or impeded or tried to

influence, obstruct, or impede a federal grand jury investigation; and

Second, the defendant acted corruptly with knowledge of a

pending federal grand jury investigation and with the intent to

obstruct the federal grand jury investigation.

ER 1A: 260-61.

B. Standard of Review.

The government claims that the jury instruction issues raised here are

reviewed for an abuse of discretion. GAB 119. The central issue is whether the

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 30 of 96(31 of 97)

22

government was permitted to proceed with an invalid legal theory – the

instructional issues relate to the court’s failing to prevent, or facilitating, the

government from proceeding on that invalid theory. The question whether the

government was permitted to proceed with an invalid theory is reviewed de

novo. United States v. Egan, 860 F.2d 904, 907 (9th Cir. 1988).

The government claims that the invalid theory issue should be reviewed

for plain error because “defendants never raised [it] before the district court.”

GAB 126. Defendants pointed out the government’s invalid theory in the

disputed jury instructions, and again in the jury instructions conference, stating

that the requested instructions were necessary because “there’s been a lot of

mention during the trial of obstructing the FBI . . . .” ER 1A: 131. The

government does not explain why this was insufficient, and it is not apparent

what more Defendants could have done to preserve the issue.

C. The Obstruction Counts of Conviction Should Be Vacated Because

the Government Pressed An Invalid Theory.

The government agrees that “[w]here a jury returns a general verdict that

is potentially based on a theory that was legally impermissible or

unconstitutional, the conviction cannot be sustained.” United States v. Fulbright,

105 F.3d 443, 451 (9th Cir. 1997) (emphasis in original), overruled on other

grounds by United States v. Heredia, 483 F.3d 913, 921 (9th Cir. 2007) (en banc);

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 31 of 96(32 of 97)

23

GAB 127. “In contrast, a reviewing court may uphold a general verdict if there

was sufficient evidence on at least one of the submitted grounds for conviction,

even if there was insufficient evidence to sustain the other theories of the case.”

Fulbright, 105 F.3d at 451 n.5. To avoid the automatic reversal that results in the

invalid theory context, the government re-casts Defendants’ claim as falling into

the insufficient evidence context, asserting that: (1) the parties’ disputes at trial

were entirely factual, not legal, see GAB 114, 126; thus (2) Defendants must be

claiming that the jury potentially convicted them based on a theory for which

there was insufficient evidence, rather than based on an invalid legal theory. See

GAB 126-29.

The government’s premise is wrong, because the parties’ disputes at trial

were not purely factual. There were legal disputes with respect to the jury

instructions that Defendants proposed to prevent conviction based on an invalid

theory. The government prevailed on those disputes, and now the question of

whether the jury potentially convicted on an invalid theory is before the Court.

Notably, in arguing that the parties’ trial disputes were purely factual the

government relies on a portion of the opening brief that it misunderstands. See

GAB 126-27 (citing JOB 58-64). In that portion, Defendants discuss “five

categories of so-called ‘obstructive conduct’” on which the government relied at

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 32 of 96(33 of 97)

24

trial, which “related almost exclusively to the FBI’s investigation.” JOB 57. The

government claims that discussion “demonstrates the parties’ dispute was

factual.” GAB 126. But, that discussion shows that the government did countless

things that incorrectly “led the jurors to believe they could convict under § 1503

if they concluded that the Defendants intended to obstruct ‘an FBI

investigation.’” JOB 57 (citing ER 2:758). That is, the discussion highlights

aspects of the government’s trial presentation that led the jury to believe it could

convict based on an invalid theory, it does not show that the parties’ disputes

during trial were purely factual.

The government’s answering brief unwittingly makes the same point,

because nearly its entire discussion of the trial evidence focuses on things

Defendants allegedly did to obstruct the FBI. See GAB 8-68. It is apparent that

none of those things, except for the alleged effort to “hide” Brown from a grand

jury, could be construed as having been done with an intent to obstruct a grand

jury proceeding.10 The government does not even argue that those things were

10 One particularly glaring example is the government’s claim that the conspiracy to obstruct a grand jury proceeding began on August 18, 2011 (GAB 15), a point at which none of the Defendants knew anything about a grand jury proceeding. See JOB 59, ER 2: 683.

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 33 of 96(34 of 97)

25

done with an intent to obstruct a grand jury proceeding. Instead, in a two-page

section at the end of its summary of the trial evidence, which is titled

“Knowledge of the grand-jury investigation,” the government says that

Defendants knew there was a “grand jury investigation” because grand jury

subpoenas had been issued to LASD. GAB 68-70. The government seems to

think that knowledge of a grand jury proceeding, coupled with an intent to

obstruct the FBI, is enough to convict, even without a showing that Defendants

specifically intended to obstruct a grand jury proceeding. It is not – indeed, it

amounts to less than the government had in Aguilar, where there was no dispute

that the defendant knew about and intended to obstruct a grand jury proceeding,

and the only question was whether he knew his conduct was likely to do so.

Having mis-cast Defendants’ invalid theory claim, the government does

not respond to it. Presumably the government has no good response.

D. The Court Erred in Denying Defendants’ Requested Instructions that

the Government Must Show that They Intended To Obstruct a

Grand Jury Proceeding, Not Just an FBI Investigation.

With respect to the district court’s refusal to instruct the jury that it had to

find Defendants intended to obstruct a grand jury proceeding, not just an FBI

investigation, the government makes two conflicting arguments.

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 34 of 96(35 of 97)

26

First, the government claims that the court did not err because other

instructions that were given “adequately covered defendants’ theory that they

merely obstructed an FBI investigation.” GAB 119-20; see also GAB 121. As an

initial matter, Defendants did not request the subject instructions because their

“theory” was that they “merely obstructed an FBI investigation.” Instead, they

requested the instructions to prevent the government from getting a conviction

based on an invalid legal theory. And the government points to nothing in the

instructions given that told the jurors that they could not convict based on

finding that Defendants intended to obstruct an FBI investigation. Given the

government’s trial presentation in this case, that risk was especially strong.

It is apparent that the government does not really believe that the

instructions given ameliorated that risk in any way, because the government also

argues that the requested instructions “were misleading,” and properly refused,

stating:

[A] defendant’s interference with law-enforcement agents

“integrally involved” in a grand-jury investigation can be sufficient to

satisfy Aguilar’s standard requiring intent to obstruct a grand-jury

proceeding rather than merely an FBI investigation “independent . . .

of the grand jury’s authority.” [Citations omitted.] Smith, Manzo, and

Leavins’s instructions suggested otherwise …..

GAB 120-21, quoting United States v. Hopper, 177 F.3d 824, 830 (9th Cir. 1999).

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 35 of 96(36 of 97)

27

The government made the same argument in the district court, where it

claimed that the instructions “would exclude a jury from finding obstruction

even if the federal agents were acting as arms of the grand jury.” ER 1A: 38, 41

(emphasis added). That argument, and most of the case law on which it is based,

was addressed in detail in the opening brief, and that discussion will not be

repeated here. But there are two key points that bear emphasizing.

First, to convict under § 1503 the government must show that the

defendant: (1) had the specific intent to obstruct a judicial proceeding, and an

intent to obstruct an FBI investigation is not enough; and (2) knew that his

conduct had the “natural and probable effect” of obstructing that proceeding.

See JOB 66-67; Aguilar, 515 U.S. at 601; United States v. Triumph Capital

Group, Inc., 544 F.3d 149, 166 n.16 (2d Cir. 2008). The first element was

announced long before the Supreme Court’s opinion in Aguilar. The second was

added by Aguilar, and it is in that context that Aguilar referred, in dictum, to the

potential significance of agents acting as “arms of the grand jury.” That language

is the basis for the government’s objection to Defendants’ proposed instructions.

Aguilar’s “arm of the grand jury” dictum indicates that it may be possible

for the government to establish that a defendant knew that his conduct was likely

to obstruct a grand jury proceeding, if it is shown that the defendant made a

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 36 of 96(37 of 97)

28

false statement to an FBI agent while knowing that the agent was acting as an

arm of the grand jury. That is, the government may rely on an “arm of the grand

jury” theory to establish the second mens rea element discussed above. JOB 69.

But the “arm of the grand jury” theory cannot be used to establish the first

element discussed above, that the defendant had the specific intent to obstruct a

judicial proceeding. If a person did not intend to obstruct a grand jury

proceeding, he may not be convicted based on his having intended to obstruct an

FBI agent (e.g., for reasons of personal or professional animus), even if he knew

that agent was acting as an arm of the grand jury.

With the proper application of an “arm of the grand jury” theory in mind,

it is apparent that the government’s objection to Defendants’ proposed

instructions – that they “would exclude a jury from finding obstruction even if

the federal agents were acting as arms of the grand jury” – was misplaced. The

proposed instructions related to the first element discussed above, to which the

“arm of the grand jury” theory does not apply. Though this point is discussed in

detail in the opening brief, JOB 66-69, and is the cornerstone of Defendants’

argument, the government ignores it. One would at least expect the government

to say whether it agrees or disagrees with this point, but it says nothing.

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 37 of 96(38 of 97)

29

While dodging this key point, the only thing that the government adds to

what it said in the district court is a selective quote from United States v. Hopper,

177 F.3d 824, 830 (9th Cir. 1999). Specifically, the government writes that “a

defendant’s interference with law-enforcement agents ‘integrally involved’ in a

grand-jury investigation can be sufficient to satisfy Aguilar’s standard requiring

intent to obstruct a grand-jury proceeding rather than merely an FBI

investigation ‘independent . . . of the grand jury’s authority.’” GAB 120 (quoting

Hopper, 177 F.3d at 830). This suggests that a defendant may be convicted

under § 1503 without the government showing that he intended to obstruct a

judicial proceeding, so long as the government shows that the defendant

interfered with FBI agents who were integrally involved in a grand jury

investigation. The government points to nothing in Aguilar, or any other case,

that indicates that the core intent element under § 1503 – the intent to obstruct a

judicial proceeding – can be short-circuited in that way.

And a closer look at Hopper belies this claim. The defendants in Hopper

argued that there was insufficient evidence to convict them for attempting to

obstruct an IRS proceeding. Though the case did not involve a § 1503(a) charge,

the Court discussed Aguilar:

The indictment alleged that Aguilar had intentionally given false

information to federal investigators who were potentially going to be

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 38 of 96(39 of 97)

30

called to testify before a grand jury. The Supreme Court held that

lying to an investigating agent who “might or might not testify before a

grand jury” did not constitute obstruction of justice. …[H]ad the

investigators been subpoenaed or summoned by the grand jury, or had

there been proof that they were acting as an arm of the grand jury,

there would have been enough to support a conviction for obstructing

a judicial proceeding. Id. at 600-02. The Court held that in order to be

indictable for obstruction of a judicial proceeding, the defendant’s

actions must have a “natural and probable effect of interfering with the

due administration of justice.” Id. at 601.

Hopper, 177 F.3d at 830.

The Court in Hopper went on to conclude that the defendants in that case

“knew” that their actions would have the “natural and probable effect” of

“prevent[ing] collection of money owed to the IRS,” and thus knew their actions

would likely obstruct an IRS proceeding. See id. In sum, Hopper recognized that:

(1) Aguilar added a materiality-type element to § 1503; (2) that element comes

with a knowingly mens rea attached; and (3) an “arm of the grand jury” theory is

relevant, if at all, to that materiality element, not to the core mens rea that the

defendant must have intended to obstruct a judicial proceeding. This last point is

the cornerstone of Defendants’ argument.

The second key point made in the opening brief is that even if the

government’s “arm of the grand jury” objection to the proposed instructions had

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 39 of 96(40 of 97)

31

merit, the solution was for the court to give Defendants’ proposed instructions

and instruct on what was necessary to convict on an “arm of the grand jury”

theory. See JOB 71. The district court did neither. That was particularly

prejudicial because the FBI case agent simply announced to the jury, “I am an

arm of the grand jury,” and the prosecutor stated that as a fact during closing.

See JOB 72 (quoting ER 2: 688; ER 6: 1756). As the case law discussed in the

opening brief shows, establishing an arm of the grand jury theory is not so

simple. JOB 71. More important, through this sleight of hand the government

converted the entire FBI investigation into “the grand jury investigation,”

substantially increasing the risk that the jury convicted based on concluding that

Defendants intended to obstruct the FBI, rather than “a grand jury proceeding.”

The government does not respond to this issue, other than to wrongly

claim that Defendants did not preserve it for appeal. GAB 120, n.28. In

responding to the government’s objection to their proposed instructions,

Defendants said that “[e]ven if it were true that interference with an agent who

was acting as an arm of the grand jury could be the basis for a conviction,” that

would not obviate the need for the requested instructions, but would instead

require “additional instruction(s) telling that to the jury and defining what the

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 40 of 96(41 of 97)

32

government must prove for an agent to be deemed an arm of the grand jury.” ER

1A: 39.

Though the government does not address the court’s failure to instruct on

an arm of the grand jury theory, its answering brief shows that whatever that

theory’s application, the evidence does not support it in this case. Specifically, in

the answering brief the government claims that the “[t]he FBI served as an arm

of the grand jury,” and cites two pages of the record as support. GAB 9. One cite

refers to Agent Dahle’s conclusory statement, “I’m an arm of the Federal Grand

Jury.” ER 2: 688. The other is to the following testimony from Agent Dahle:

Federal grand jury subpoenas were issued on behalf of the grand jury.

Things that were produced pursuant to those subpoenas were

produced to the grand jury. Testimony – the grand jury heard

testimony from witnesses before it. And agents would interview

witnesses and then sometimes present that testimony to the grand jury.

ER 2: 651.

This case does not involve any claims of obstruction with respect to grand

jury subpoenas, nor claims that Defendants tried to influence the testimony of

grand jury witnesses. Thus, the only portion of the quoted testimony that could

support an “arm of the grand jury” theory is that “agents would interview

witnesses and then sometimes present that testimony to the grand jury.”

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 41 of 96(42 of 97)

33

Considered in light of the other evidence presented, this means that the

government’s “arm of the grand jury” theory boils down to claiming: (1)

Defendants did things with respect to people that they knew, or suspected, FBI

agents wanted to interview; (2) the things Defendants did might have affected the

FBI agents’ interactions with those people; and (3) that in turn could have

affected the testimony that FBI agents might (i.e., “sometimes”) give to the grand

jury.11 That is far more attenuated than what happened in Aguilar, where the

defendant intended to obstruct the grand jury, and lied to agents about a subject

that he knew a grand jury was considering. The Court in Aguilar nonetheless

held, “We do not believe that uttering false statements to an investigating agent –

and that seems to be all that was proved here – who might or might not testify

before a grand jury is sufficient to make out a violation of the catchall provision

of § 1503.” 515 U.S. at 600. Considering that the “[t]he government did not show

. . . that the agents acted as an arm of the grand jury” in Aguilar, id., it is hard to

know how the government thinks any sort of arm of the grand jury theory was

11 This discussion highlights the novelty of the government’s theory is in this case, because it does not involve submitting false documents to the grand jury, lying to the grand jury, or trying to convince someone to do either of those things.

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 42 of 96(43 of 97)

34

established in this case.12 And without a valid argument in that regard, the

government’s objection to the requested instructions falls flat.

E. The Court Erred in Instructing the Jury that It Could Convict If It

Found that Defendants Intended to Obstruct “the Grand Jury

Investigation,” Rather that “a Grand Jury Proceeding.”

The district court committed a second instructional error when it told the

jurors that they could convict if they found that Defendants “acted corruptly . . .

with the intent to obstruct the federal grand jury investigation.” ER 1A: 261

(emphasis added). As discussed in the opening brief, given the evidence

presented “the only logical way for the jurors to understand the phrase ‘the

federal grand jury investigation’ was that it encompassed anything that the FBI

did as part of its investigation.” JOB 74.

The government ignores this argument and instead focuses on

Defendants’ related argument that the instruction’s language is contrary to a

wealth of case law that indicates that the government must show that a

defendant intended to obstruct a “specific” judicial proceeding. See JOB 73-74.

With respect to the latter argument, the government complains that “defendants

12 Notably, the government did not establish that any Defendant expected Agent Marx, or any other FBI agent, to testify in a grand jury proceeding.

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 43 of 96(44 of 97)

35

cite no case supporting the proposition that a defendant must know precisely

which grand jury he obstructs,” and argues that, “[i]n any event, the evidence

overwhelmingly demonstrated defendants’ endeavor to obstruct any and all

grand-jury proceedings into abuse at LASD-operated jails.” GAB 123-24. As for

the first claim, Defendants cited several cases that indicate that a defendant must

intend to obstruct a “specific” grand jury proceeding, and that is not consistent

with the government’s theory that the Defendants could be convicted based on

an alleged intent to obstruct a “grand jury investigation” that encompassed an

unknown number of grand juries that were in session during unknown time

periods. See JOB 73. As for the government’s “any and all” approach, that does

not square with “[c]ourts hav[ing] construed the ‘proceeding’ element fairly

strictly,” and with the requirement that the government show the defendant

intended to obstruct a pending judicial proceeding. Fulbright, 105 F.3d at 450.

The government also argues that courts use the phrases “grand jury

investigation” and “grand jury proceeding” “interchangeably,” thus “[t]he

distinction between the two is immaterial.” GAB 122. Although the two phrases

can be used interchangeably in some contexts without creating problems that is

not the case where, as here, the government leads the jury to believe that “an FBI

investigation” is also interchangeable with “a grand jury investigation.” JOB 74-

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 44 of 96(45 of 97)

36

76. Furthermore, the government mashes all of these concepts together under

the umbrella “the federal investigation,” a phrase it uses dozens of times in the

answering brief, and used countless times during trial. By using this phrase, the

government makes no distinction between a grand jury proceeding, a grand jury

investigation, and an FBI investigation. That is no accident – the government

wanted the jury to equate an intent to obstruct an FBI investigation with an

intent to obstruct a grand jury proceeding.

F. The Court Erred in Failing to Instruct the Jury that Defendants Had

to Know Their Conduct Was Likely to Influence a Grand Jury

Proceeding.

The district court also erred by failing to instruct the jury that Defendants

had to know their conduct had the “natural and probable” effect of influencing a

grand jury proceeding.

The government first claims that this issue was waived. This issue is

reviewed for plain error, and may also be considered in the context of assessing

the cumulative prejudice from multiple errors. See United States v. Perez, 116

F.3d 840 (9th Cir. 1997) (en banc); JOB 77.

As for the merits, the government says that Defendants “cite no case

requiring the instruction they propose.” GAB 124. But Aguilar makes clear that a

defendant may not be convicted if he “lacks knowledge that his actions are likely

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 45 of 96(46 of 97)

37

to affect the judicial proceeding,” and if he did not “kn[o]w that his false

statement would be provided to the grand jury.” 515 U.S. at 599, 601 (emphasis

added). And as emphasized in the opening brief, the Second Circuit addressed

this issue clearly and persuasively in Triumph Capital, 544 F.3d at 166-68.

Next the government says that because the jury was instructed that it had

to find that the Defendants “intend[ed] to obstruct the federal grand-jury

investigation . . . any additional reference to the Defendants’ knowledge of the

likely effect of their actions would have been redundant.” GAB 124-25. To

support this argument, the government cites what the Second Circuit has

described as “puzzling” language in Aguilar that seems to equate (1) § 1503’s

core intent to obstruct a grand jury proceeding element with (2) the materiality

plus knowledge element that was the change wrought by Aguilar. See Triumph

Capital Group, Inc., 544 F.3d at 166 n.16. Despite that language, it is clear from

the following excerpt in Aguilar that a showing of mens rea beyond an intent to

obstruct a judicial proceeding is required:

Justice Scalia also apparently believes that any act, done with the

intent to “obstruct . . . the due administration of justice,” is sufficient to

impose criminal liability. Under the dissent’s theory, a man could be

found guilty under § 1503 if he knew of a pending investigation and

lied to his wife about his whereabouts at the time of the crime,

thinking that an FBI agent might decide to interview her and that she

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 46 of 96(47 of 97)

38

might in turn be influenced in her statement to the agent by her

husband’s false account of his whereabouts. The intent to obstruct

justice is indeed present, but the man’s culpability is a good deal less

clear from the statute than we usually require in order to impose

criminal liability.

515 U.S. at 602.

The reason the man is not liable is not because he lacked the core intent to

obstruct a grand jury proceeding, it is because he did not know that his actions

would likely obstruct a grand jury proceeding.

Finally, the government argues that Defendants do not claim that the

failure to instruct on this mens rea element “affected the outcome of their trial . .

. .” GAB 124. To the contrary, the opening brief states that “[w]hen considered in

combination with the other instructional errors discussed above, the upshot is

that the jurors were never told that to convict they had to find that Defendants

(1) specifically intended to obstruct a grand jury proceeding, and (2) knew that

their conduct was likely to affect a grand jury proceeding.” JOB 76-77. Without

those, and the other, requested instructions, there was no brake on the jury

convicting based on finding that Defendants intended to obstruct an FBI

investigation. See JOB 77.

Case: 14-50440, 05/20/2016, ID: 9986030, DktEntry: 92, Page 47 of 96(48 of 97)

39

III. The Court Erred in Precluding the Testimony of Paul Yoshinaga, a Key

Defense Witness.

The district court wrongly excluded the testimony of Paul Yoshinaga,

LASD’s Chief Legal Advisor, which was critical to the good faith and lack of

mens rea defense advanced by Leavins and the other Defendants, on the ground

that: (1) it was not relevant because Leavins was not entitled an advice of counsel