423.full

-

Upload

agentia-ronet -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

1

description

Transcript of 423.full

-

http://anj.sagepub.com/Criminology

Australian & New Zealand Journal of

http://anj.sagepub.com/content/43/3/423The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1375/acri.43.3.423 2010 43: 423Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology

Rebecca L. WickesContext

Generating Action and Responding to Local Issues: Collective Efficacy in

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Australian and New Zealand Society of Criminology

can be found at:Australian & New Zealand Journal of CriminologyAdditional services and information for

http://anj.sagepub.com/cgi/alertsEmail Alerts:

http://anj.sagepub.com/subscriptionsSubscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navReprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navPermissions:

What is This?

- Dec 1, 2010Version of Record >>

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

423THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGYVOLUME 43 NUMBER 3 2010 PP. 423443

Address for correspondence: Rebecca L. Wickes, School of Social Science, The University ofQueensland, Brisbane, QLD 4072. E-mail: [email protected]

Generating Action and Responding toLocal Issues: Collective Efficacy in ContextRebecca L. WickesThe University of Queensland, Australia

Recent research suggests that communities can be collectively effica-cious without dense networks and kith and kinship relations. Yet fewstudies examine how collective efficacy is generated and sustained in theabsence of close social ties. Using in-depth interviews with local residentsand key stakeholders in two collectively efficacious suburbs in Brisbane,Australia, this study explores the role of social ties and networks inshaping residents sense of active engagement and perceptions of commu-nity capacity. Results suggest that strong social bonds among residents arenot necessary for the development of social cohesion and informal socialcontrol. Instead, collective representations or symbols of communityprovide residents with a sense of social cohesion, trust and a perceivedwillingness of others to respond to problems of crime and disorder. Yetthere is limited evidence that these collectively efficacious communitiescomprise actively engaged residents. In both communities, participantsreport a strong reliance on key institutions and organisations to manageand respond to a variety of problems, from neighbourhood nuisances tocrime and disorder. These findings suggest a more a nuanced understand-ing of collective efficacy theory is needed.

Keywords: collective efficacy, social networks, community, crime prevention, crime

Systemic models of community regulation position social ties as necessary forachieving common goals and solving collective problems (Bursik & Grasmick,1993; Hunter, 1985; Kornhauser, 1979; Sampson & Groves, 1989). Yet some schol-ars view this model of community as outdated. Robert Sampson suggests thatattachment to the contemporary community is voluntary, instrumental and tied torational investments (1999, p. 245) and social organisation is independent ofstrong social ties (Sampson, 1999, 2002, 2006). Instead, communities with weakpersonal and social ties can be effective units of social organisation if a working trustand shared expectations for local social control are present. Sampson claims it isthis collectively efficacious nature of a community, rather than dense ties or socialnetworks that constitutes the more proximate social mechanism for understandingbetween-neighbourhood variations in social disorder and crime.

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

Although much support for collective efficacy theory exists, there is limitedresearch that qualitatively explores the tenets of this theory in context. Studies thatuse large-scale surveys to examine the relationship between collective efficacy andcrime do not illustrate how residents develop and sustain a working trust and expec-tations for social control when relationships are diffuse. With the exception ofCarrs (2003) ethnographic study on informal social control in Beltway, Chicago,there is little to suggest how residents garner a sense of collective efficacy incontemporary urban communities.

The goal of this article is to examine how residents accounts of their communityresonate with the broader theoretical tenets of collective efficacy. It does not attemptto provide an ethnographic account of community life akin to studies inspired byHerbert Gans (1967). Rather, the focus is to assess whether the current criminologicalinterpretation of collective efficacy reflects the accounts of residents. This articletherefore focuses on how residents define community and assesses the form andfunction of intracommunity relationships in two collectively efficacious communities.From the accounts of residents and key informants, an investigation is undertakeninto the mechanisms that promote collective efficacy. Finally, the situated processesrelative to specific tasks such as maintaining public order (Morenoff et al., 2001, p.521) and the extent to which these processes represent the active sense of engage-ment on the part of residents (Sampson, 2006, p.155) are examined.

Community Regulation and the Role of Social RelationshipsThe existence of stable, social networks is a central tenet of systemic models ofcommunity regulation, like social disorganisation. Until the mid 1990s, researchwas therefore primarily concerned with the mediating effects of social networks oncrime and several studies convincingly demonstrated the salience of social relation-ships in regulating group behaviour (Bursik, 1988; Hunter, 1985; Sampson, 1988;Sampson & Groves, 1989; Skogan, 1986). Hunter (1985) and Bursik and Grasmick(1993) pointed to the importance of private, parochial and public social control inreducing crime and achieving social order. At each level of social control, differentrelational networks were needed. For private control, the role of intimate kith andkin groups deterred unwanted behaviour and lessened the effects of ostracism anddeprivation. Parochial control, which played a significant role in the control ofcrime, relied on relationships among neighbors who do not have the same senti-mental attachment (Bursik & Grasmick, 1993, p. 17). Finally, public social control,or the ability to obtain essential services from external sources, centred on looseconnections both exogenous and endogenous to the community. The relationshipbetween these levels of social control and delinquency was illustrated in Sampsonand Groves (1989) research in the United Kingdom. In this study they identifiedthe most salient community characteristics that mediated the effects of disadvan-tage on crime and victimisation. These included the number of social ties, connec-tions to organisations and the willingness of residents to deter unwanted behaviour.Additionally, Wesley Skogans (1986, 1989, 1990) research supported the systemictenets of community regulation. Skogan found that fear had direct and negativeconsequences for community regulation as it weakened the development of keysocial ties necessary for generating collective action.

424

REBECCA L. WICKES

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

While much research supports the prosocial benefits associated with socialrelationships and/or networks (Coleman, 1988; Drukker, Kaplan, Feron, & van Os,2003; Gibson, Zhao, Lovrich, & Gaffney, 2002; Hendryx & Ahern, 2001; Israel,Beaulieu, & Hartless, 2001; Kawachi, Kennedy, Lochner, & Prothrow-Stith, 1997;Kennedy, Kawachi, Prothrow-Stith, Lochner, & Gupta, 1998; Noguera, 2001),many note that both the role and the function of the urban community havechanged dramatically and strong ties are no longer the norm in many urbancommunities (Morenoff et al., 2001, p. 520; see also Bauman, 2001; Day, 2006;Giddens, 1991). Moreover, for some communities characterised by high levels ofcrime, strong friendship and family ties may impede the ability to stem disorder(Pattillio, 1998) or result in a parochial culture where collective responses toproblems are not possible (Wilson, 1987). Thus some view the urban villageconcept, which underpins systemic models of community regulation, as outdatedand instead call for a more contemporary understanding of the differential ability ofneighbourhoods to prevent crime and social disorder (Sampson, 2002, 2006).Critiquing the disproportionate focus on social ties, Sampson and his colleaguessuggest a closer examination is needed of the process of activating or convertingsocial ties into the desired outcomes for the collective (Sampson et al., 1999). Theyargue that the collective capacity for social action, even if rooted in weak personalties, may constitute the more proximate social mechanism for understandingbetween neighborhood variation in crime rates (Morenoff et al., 2001, p. 521).

The collective capacity of communities or, collective efficacy is defined as anactivated process that seeks to achieve an intended effect (Sampson et al., 1997, p.919), as it differentiates the process of activating/converting social ties to achievethe desired outcomes from the ties themselves (Sampson et al., 1999, p. 635). Bystating that social ties may foster the conditions under which collective efficacy may flour-ish but are insufficient for the exercise of control (Sampson, 2002, p. 220, emphasis inoriginal), Sampson makes the theoretical and empirical distinction between onespotential stocks of social capital accumulated through social ties and a collectivebelief in the capacity of residents to achieve an intended, specific outcome (i.e.,collective efficacy).

Collective efficacy was originally coined by Albert Bandura (1995, 1997, 2001)as a component of his social cognitive theory. It is an extension of self-efficacy,which can best be understood in terms of peoples capacity to act based upon theirperceptions of individual control. Collective efficacy is based upon this sameperspective but is defined as a groups shared belief in its conjoint capabilities to organizeand execute the courses of action required to produce given levels of attainments(Bandura, 1997, p. 477, emphasis in original). Collective efficacy is positioned asseparate to the sum of individual attributes and focuses on the emergent propertiesof a group that are central to group level performance. Bandura (1995, 1997, 2001)argues that modern societys requirement for the interdependence of humanfunctioning places a premium on the exercise of collective agency through sharedbeliefs in the collective power to produce effects. In social psychology, collectiveefficacy theory therefore provides a way to explore the relationship between collec-tive perceptions and outcomes.

In criminology, collective efficacy has been adapted and extended from socialpsychology to examine the differential ability of communities to prevent crime

425

COLLECTIVE EFFICACY IN CONTEXT

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

and/or disorder. It is seen as a more useful and contemporary theoretical frameworkof community organisation for two reasons: First, collective efficacy theory can beeffectively operationalised to examine the extent to which neighbourhoods (asopposed to individuals) can mobilise resources effectively to remedy problems.Indicators of collective efficacy are based on ecometic items which, according toRaudenbush and Sampson (1999), differ from psychometric measures in that theymeasure perceptions of a collective rather than an individual attribute (see Table 1for a list of the items that measure the two constructs that comprise the collectiveefficacy scale). Second, unlike systemic models of community regulation, collectiveefficacy does not depend on the presence of strong interpersonal ties thus allowingresearch to move beyond the dense ties dilemma that has beleaguered urban crimi-nology (Sampson, 2002).

There is much support for collective efficacy theory in the criminological litera-ture. Results from large-scale surveys in the United States, Australia, the UnitedKingdom and Sweden demonstrate that collectively efficacious communities havelower crime (Mazerolle, Wickes, & McBroom, in press; Oberwittler & Wikstrm,2006; Sampson et al., 1997; Sampson & Wikstrm, 2004, Wikstrm, 2006). Yet, nostudy has qualitatively examined collective efficacy in situ and only limited researchexists that specifically explores how informal social control is achieved in communi-ties characterised by weak ties. An exception is Patrick Carrs research in Beltway,Chicago. Departing from Bursik and Grasmicks (1993) systemic model of commu-nity regulation, Carr (2003) demonstrates that the regulatory ability of communitiesis not dependent on private levels of social control. Drawing on his experiences andinterviews with community activists, he suggests that informal social control works without dense network ties because the strategies employed do not owe theirexistence or efficacy to social ties (2003, p. 1250). Carrs study focuses primarily onthe connections between community activists and extralocal organisations and theprocesses associated with harnessing the skills and the resources of institutions (likethe police department) to enhance informal social control. The interdependence ofcommunity groups and key institutions in Beltway, or what Carr calls the newparochialism, increases levels of informal social control. This interdependence canresult in reduced levels of crime and disorder in communities where relationships arelargely instrumental. However, in Carrs research this only became possible becauseresidents could procure the support and services of public institutions.

The Present ResearchLimited research exists that provides an illustration of how expectations for socialaction emerge or are understood in collectively efficacious communities and howthis relates to residents actions. Although Carrs (2003) Beltway study provides richinsight into the ways in which activists and organisations can work in tandem toreduce crime, it does not illustrate how informal social control is engendered incommunities without strong and active links to formal institutions, nor does itexamine the key tenets of collective efficacy theory. The goal of the presentresearch, therefore, is to examine three key claims from the extant collectiveefficacy research in two collectively efficacious residential communities. First,research indicates that contemporary urban communities are not organised in a

426

REBECCA L. WICKES

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

parochial, local fashion (Morenoff et al., 2001, p. 520) and that the urban villagedoes not exist in practice (see Wellman, 1999). But have residents moved beyondthis imagery of community? If, as Day (2006, p. 246) states, community is under-stood best as an imaginative tool used by people as they go about their business ofconstructing an idea of a better society, how is community imagined and does thisimagery facilitate or hinder residents as they go about their business of preventing orcontrolling crime?

The second claim is that communities with weak ties can be effective units ofsocial control (Morenoff et al., 2001; Sampson, 2002, 2006; Sampson et al., 1997,1999). As strong relationships no longer characterise contemporary urban communi-ties, this article examines how a strong, conjoint belief in the capacity of the collec-tive is engendered in communities with weak ties. It addresses how residents learnthe norms surrounding action, if not via social relationships, and illustrates thecollective representations that are likely to lead to the development of this belief.

The third claim is that collective efficacy depicts a task-specific process repre-senting the active engagement of local residents. That is, in collectively efficaciouscommunities, people with loose affiliations will work together to achieve a desiredgoal. The qualitative analysis that follows investigates whether residents collaborateon crime prevention and considers the role key institutions play in generating orpromoting collective efficacy among residents.

427

COLLECTIVE EFFICACY IN CONTEXT

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

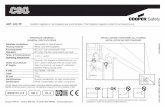

TABLE 1

Collective Efficacy Items in the PHDCN

Informal social control/willingness to intervene Social cohesion/trust

1. If a group of neighborhood children wereskipping school and hanging out on a streetcorner, how likely is it that your neighborswould do something about it?

1. People around here are willing to help theirneighbors? Would you say you stronglyagree, agree disagree or strongly disagree?

2. If some children were spray-painting graffition a local building, how likely is it that yourneighbors would do something about it?

2. This is a close-knit neighborhood? Wouldyou say you strongly agree, agree disagreeor strongly disagree?

3. If there was a fight in front of your house andsomeone was being beaten or threatened,how likely is it that your neighbors wouldbreak it up?

3. People in this neighborhood can be trusted.Would you say you strongly agree, agreedisagree or strongly disagree?

4. If a child was showing disrespect to an adult,how likely is it that people in your neighbor-hood would scold that child?

4. People in this neighborhood generally dontget along with each other. Would you sayyou strongly agree, agree disagree orstrongly disagree?

5. Suppose that because of budget cuts the firestation closest to your home was going to beclosed down by the city. How likely is it thatneighborhood residents would organize to tryto do something to keep the fire station open?

5. People in this neighborhood do not sharethe same values. Would you say you stronglyagree, agree disagree or strongly disagree?

Source: Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods, 1995

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

MethodologyThe present study draws on the Collective Capacity Study (CCS), which examinesthe spatial distribution of collective efficacy, crime and disorder across 82 StatisticalLocal Areas (SLAs)1 in the Brisbane Statistical Division (BSD) in Queensland,Australia. The CCS included the full complement of items used in the Project onHuman Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN) research to measurecollective efficacy (see Table 1). From the CCS, two collectively efficacious areaswere selected: Hidden Valley and Redwood Estate. These communities fell into the20th percentile of the 82 SLAs on the collective efficacy scale with Hidden Valleythe second highest scoring SLA in the sample. Both sites also fell into the topquartile of socioeconomically advantaged SLAs as determined by their position onthe Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) SEIFA Index of Relative Disadvantage(ABS, 2001). From the Queensland Police Service crime incident data, HiddenValley had extremely low crime rates (with the second lowest crime incident rate).However, despite Redwood Estates high collective efficacy score, it fell into the top20th percentile in the sample for total crime incidents.

I purposively selected efficacious communities to examine the central tenets ofcollective efficacy theory. Choosing an SLA with a classic disadvantage profilewould only confirm what other scholars have articulated (see Anderson, 1990, 1999;Shaw & McKay, 1931/1999; Wilson, 1987, 1996). Specifically that unemployment,the deskilling of the labour force, population instability, the lack of public assistance,poor access to education, poor health, inadequate housing and marital breakdown allimpede the formation of the social organisation necessary to collectively respond tocrime and disorder. In this regard, exploring the factors associated with high crimerates in a disadvantaged setting would not make a material contribution to theecology of crime literature, or the development of collective efficacy theory.

The selection of two reasonably affluent, highly efficacious communities materi-ally contributes to the literature in three ways. First, while much research exists ondisadvantaged communities, there are no studies that examine collective efficacy inaffluent settings. The results from the PHDCN shows that concentrated disadvan-tage and concentrated affluence are strong predictors of collective efficacy andcrime (Morenoff et al., 2001). But, as Sampson has stated, research is overlyconcerned with the poverty paradigm with its attendant focus on the outdatedconcept of the inner city (2002, p. 216). Girling, Loader and Sparks also commenton the paucity of research on affluent communities and note the absence withincriminology of any established tradition of writing about relatively prosperouscommunities (2000, p. 84). Thus, research has focused almost exclusively on whypoverty matters in understanding high crime rates, without a concomitant approachto explore how and if wealth matters in controlling crime. Second, my selection ofthese two study sites supports Sampsons suggestion to move away from a focus oninner city suburbs, which in Australia tend to have a higher socioeconomic stand-ing (for example consider Paddington in Sydney or New Farm in Brisbane). Thesites in the present study are located some distance from the city centre and providea contrast to the more densely populated city suburbs found in so much of theecological research. Third, the selection of a deviant case (e.g., a suburb with highcrime incident rates and high levels of collective efficacy), provides an opportunityto assess how collective efficacy is maintained in a high crime environment.

428

REBECCA L. WICKES

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

The Contours of Hidden Valley and Redwood EstateThe first of the study sites is Hidden Valley2, which is located west of Brisbanescentral business district (CBD). Over the past 20 years, this area has changeddramatically with the development of several subdivisions and a significant increasein professional residents. At the time this research was conducted, the population ofHidden Valley was 2,263, representing a 36% increase since 1996 (ABS, 2001). Themedian age in this area was 39 years and the majority of residents were married andAustralian-born. Approximately one third of population had university qualifica-tions and the median weekly individual income was $500 to $599 per week.

Apart from a public primary school, an environmental education centre and asmall local hall, there are no services available in Hidden Valley and residents travelto neighbouring areas to access shopping centres, doctors offices, service stationsand restaurants. The majority of residents in Hidden Valley live on life-styleacreage ranging in size from 1 to 10 acres of land. Although the area has a ruralfeeling, the population of Hidden Valley has full access to town water, electricityand waste management services.

The second site is Redwood Estate, a master planned residential estate locatednorth of the CBD in the SLA of Abbotsford. Redwood Estate is a holisticallyplanned suburban residential development with a population expected to grow to25,000 over the next decade. It differs from a gated community in that entry to theestate and all services within the estate are open to the public. Redwood Estateencompasses the majority of residential properties for the SLA. At the 2001 census,the population of Abbotsford had increased by 126% from the previous census(ABS, 2001). The demographics of this SLA point to a young, predominantlyAustralian-born population with a median age of 30 years. Just over 8% of thepopulation had university degrees or postgraduate qualifications and the medianindividual weekly income was $400 to $499 (ABS, 2001).

Redwood Estate provides many services and facilities for its residents and thosein neighbouring communities. There is a large shopping complex with dining facili-ties and future plans include more retail outlets and a cinema complex. There is alarge multipurpose facility comprising a public library, an indoor swimmingcomplex, three local schools and two childcare centres. Redwood Estate is aestheti-cally pleasing with artificial lakes and wetlands, walking trails and bike tracks andparks and playgrounds. The residential areas are located in separate developer-created villages, with names such as Blue Water, Crestmeade and Edenvale. Themajority of residences in this area have immaculately groomed lawns and gardenareas with few cars parked on the street.

Selecting the SampleQualitative research rarely employs probability sampling to generate a representa-tive subset of the studied population (Neuman, 2006). Rather, the goal is to ensurethat the chosen participants are theoretically and empirically relevant to the topicbeing investigated (Flick 1998; Mason, 1996). Often in qualitative studies, purpo-sive, snowball or quota techniques are used and include as many respondents asneeded to reach saturation of the data (Strauss & Corbin, 1997). For the presentstudy, I chose participants for the in-depth interviews from a subset of respondents

429

COLLECTIVE EFFICACY IN CONTEXT

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

who had participated in the CCS. The CCS sample was derived from a randomprobability sampling frame using random digit dialling and was largely representa-tive of the Greater Brisbane Statistical Division (see Mazerolle et al., in press). Inthe survey, a question asked participants if they would participate in future research,with approximately 67% agreeing to a follow-up interview. At the time of thesurvey, 62% of Hidden Valley residents (N = 13) and 58% of Redwood Estate (N =15) agreed to participate in the follow-up interview. These residents provided theirtelephone numbers and their contact names to the CCS research team.

To ensure the profile of those willing to proceed did not significantly differ fromthose unwilling to continue with the research, I compared their relevant demo -graphics and responses on the collective efficacy scale for each group. As the samplesize was too small to conduct any statistical tests, I examined the means andmedians for variables with ordinal response categories (including age, number ofdependent children, length at current address and annual income) and percentagesfor the categorical demographic variables (gender, marital status, country of birthand level of education). As indicated in Tables 2 and 3 there were some differencesworth noting. In Hidden Valley, younger people and Australian-born residents weremore likely to refuse to participate in an interview. In Redwood Estate, thoseunwilling to continue were more likely to be unmarried, overseas-born and, interest-ingly, reported slightly higher levels of collective efficacy. In both areas, men weremore likely to continue with future research than women.

Approximately six months passed between the residents participation in theCCS and the subsequent interview. In Hidden Valley, I interviewed 10 of the 13residents who had originally agreed to a follow-up meeting (77%). The final samplecomprised seven men and three women. The response rate was lower in RedwoodEstate with 10 out of the 15 (67%) residents agreeing to be interviewed. A total offive women and five men were interviewed.

The separate sample of key informants was selected on the basis of their rolewithin the community (Houston & Sudman, 1975; Krannich & Humphrey, 1986;Kreps, Donnermeyer, Hurst, Blair, & Kreps, 1997; Nuehring & Raybin, 1986). Foreach area, I contacted the local council member and the principal of the localpublic school. I also met with the developer of the Redwood Estate. Additionally, Iused my interviews with local residents to source additional community leaders. InRedwood Estate I was referred to a local police officer, a senior member of theNeighbourhood Watch Group, an editor of one of the local newspapers and thePresident of the Local Progress Association. Hidden Valley residents were not awareof any community leaders; however, the local council member and school principalreferred me to two voluntary associations a land care group and a local commu-nity group. The total number of key informants numbered four and six for HiddenValley and Redwood Estate respectively.

Analysing the InterviewsPawson (1996) suggests that a theory-driven model places the theory as thesubject matter of the interview, and views the respondent or the participants roleas confirming, falsifying or refining the elements of the theory under investiga-tion. For this research, the participants views and attitudes were central to

430

REBECCA L. WICKES

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

431

COLLECTIVE EFFICACY IN CONTEXT

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

TABLE 3

Descriptive Statistics for Interview Participants (N = 15) and Non-Participants (N = 12) for RedwoodEstate

Yes Follow-Up Interview No Follow-Up Interview

Age 4044 years 4044 yearsNumber of dependent children 1 1Length at current address 12 months to less than 2 years 12 months to less than 2 yearsApproximate annual income $40,000 to $59,999 $40,000 to $59,999Gender

Male 29% 100%Female 71%

Marital statusMarried 88% 67%Not married 12% 33%

Country of birthAustralia 77% 50%Other 23% 50%

Level of educationPrimary/secondary only 47% 30%Trade 18% 50%University qualifications 35% 20%

Collective efficacy 8.82 9.67

TABLE 2

Descriptive Statistics for Interview Participants (N = 13) and Non-Participants (N = 8) for HiddenValley

Yes Follow-Up Interview No Follow-Up Interview

Age 5054 years 4044 yearsNumber of dependent children 1 2Length at current address 5 years to less than 10 years 5 years to less than 10 yearsApproximate annual income $80,000 or more $80,000 or moreGender

Male 69% 12%Female 31% 88%

Marital statusMarried 92% 88%Not married 8% 12%

Country of birthAustralia 54% 75%Other 56% 25%

Level of educationPrimary/secondary only 15% 12%Trade 15% 12%University qualifications 70% 76%

Collective efficacy 8.54 9.75

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

examining the tenets of collective efficacy theory and the interview schedule wasconceptually focused around these. The key theoretical activity in developing theinterview themes was to create questions that would uncover the mechanismsthat relate to collective efficacy in each area. Therefore, I relied on the centralclaims from the PHDCN and the theoretical and empirical gaps in the collectiveefficacy literature to guide the development of the interview schedule for infor-mants and residents.

Interviews lasted between 45 to 90 minutes. They were recorded and latertranscribed by a professional transcription company. Analysis occurred throughoutthe data collection period and as new themes emerged, they were incorporated intothe interview schedule. Data were analysed by creating thematic tables and thenassessing the correspondence of the coded data to the developed categories. Thesetables ensured that (1) the coded data fit the subcategory within the context ofother data comprising this field and (2) the data comprising these subcategoriesresonated with the higher categorical structure.

ResultsCommunity ImaginedThe first aim of this article was to explore how residents in two collectively effica-cious communities defined and experienced community and intracommunityrelationships. In Hidden Valley and Redwood Estate, traditional conceptualisationsof community featured strongly in the minds of residents. In both sites, communitywas defined in terms of interpersonal connections and relationships with otherpeople, and as a place where people share common interests and values. For Ian, aresident of Redwood Estate, community meant Social networks the supportnetworks to sustain the area that you live in community needs to be somewhereto be able to support your family needs, your personal needs, support with your day-to-day living.

Collective interests were viewed as more important than individual pursuitswhen describing community. Using an analogy of weaving, Ryan, a Hidden Valleyresident, believed common values were an essential element of the communityconcept:

My main understanding of community describes the weave or texture that makes thecloth, by which most members of this or that society function. Not unlike the weaveof a tartan or the spin of a Thai Silk. Its by the reconciliation of a common patternby which we function best. To go against that pattern, would bring up a flaw withinthe cloth. Thats what I understand of community.

All interviewees characterised community by strong ties and face-to-face interac-tions. Over a century ago, Tonnies stated that the force of Gemeinschaft persistsalthough with diminishing strength, even in the period of Gesellscaft, and remainsthe reality of social life (1955, p. 272). Despite limited social ties and networks intheir communities (described below), the way people imagined community inHidden Valley and Redwood Estate provided a mental map of how things ought to be(Day, 2006). The urban village concept was, at least in theory, alive and well amongthe residents in the present research. However, there was significant disparity

432

REBECCA L. WICKES

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

between how community and community relationships were imagined and howthey functioned.

In Hidden Valley and Redwood Estate, people perceived themselves as living inclose-knit communities where people relied on each other for social and instrumen-tal support. But this view did not align with their accounts of day-to-day relation-ships and interactions. Many participants lived in the community, but were notnecessarily of the community. Intracommunity friendships were few in number andonly a small minority of interviewees participated in either formal or informalcommunity organisations. In both areas, intracommunity relationships primarilyexisted among immediate neighbours and even these relationships were limited. Incontrast to what would be expected from the systemic model of community regula-tion proposed by Bursik and Grasmick (1993), few reported affective relationshipswith fellow residents. Social interactions, for the most part, were not structuredaround common leisure interests or pursuits but were more instrumental, concernedwith general community interests. In Hidden Valley, even if residents consideredtheir neighbours as friends, no one would ask others for money, even in the case ofan emergency, nor would they discuss problems of a personal nature. When I askedGus from Hidden Valley what he could ask of his friends in the community, hereplied, time and sweat, that is about it. This view was shared by Redwood Estateresidents. Although most people interviewed knew their immediate neighbours, fewreported that they mixed with their neighbours socially. They were happy to sayhello when out gardening or to spend five minutes over the fence talking aboutplants or building materials, but again the boundaries of friendships were clear.Neighbours were helpful when assistance with small tasks was needed, but were notseen as being appropriate for emotional support or affective relationships.

Symbolising Social Cohesion in the Absence of Strong TiesThe second goal of this article was to explore what influences residents in commu-nities with weak ties to perceive high levels of social cohesion and a shared identity.In Hidden Valley and Redwood Estate, relationships were limited in form andnumber, yet participants believed they lived in cohesive communities and reportedsharing similar values with their fellow residents. This sense of community was animportant driver in the high levels of collective efficacy reported in each locale inthe CCS and, drawing on the accounts of residents, was generated through collec-tive representations, both assumed and observed, of community life.

In Redwood Estate common values were assumed through two primary mecha-nisms: local newsletters and the aesthetic presentation of private dwellings andpublic spaces. With the rapidly growing population in Redwood Estate, the dissemi-nation of information through newsletters promoted a sense of community. Theyalso provided clear community norms and expectations and were viewed as a vitalsource of community information. There were three newsletters circulated through-out the area: The Redwood Messenger, The Gum Nut News (the editor a Redwoodresident) and the Gum Nut Progress Association Newsletter. In every house I visited,the latest copy of The Redwood Messenger, a glossy free weekly newsletter, adornedthe kitchen bench, the coffee table or the front hall. For the residents of RedwoodEstate, the newsletters projected common values and a sense of community and

433

COLLECTIVE EFFICACY IN CONTEXT

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

alerted them to the types of problems in their area and the communitys capacity torespond to such issues. Charlottes account provides support for this. Although shewas one of the few participants who reported spending time with fellow residents,when asked what guided her perceptions of community cohesion, she did not drawon her day-to-day relationships with others, but referred to the newsletters: I see itreflected in our local paper just people are interested in people trying to solveproblems and there just seems to be a real interest in other people.

In addition to providing a symbol of community, The Redwood Messenger actedas a mechanism of informal social control, providing residents with information onwhat was considered appropriate behaviour or conduct within the community. Forexample, the Raves and Rants column detailed concern about local issues. Allresidents interviewed were avid readers of this column and viewed it as a forum toout local residents or organisations for doing the wrong thing. They read thiscolumn to obtain information on who or what to avoid. Ian was a regular reader ofthe newsletter and knew that if someone stepped out of line in Redwood, it wouldbe there for all to see:

They have the Redwood News or whatever and they have Raves and Rants sopeople dob in other people they just say so-and-so was doing such-and-such so thewhole community kind of knows that there are people that arent doing the rightthing And then it goes on for about six weeks to and fro.

Benedict Anderson (1983) argued that the most powerful mechanism in promotingnationalist ideology across diverse groups was the rise of print media, the conver-gence of capitalism and print technology on the fatal diversity of human languagecreated the possibility of a new form of imagined community (1983, p. 49). Suchdissemination of information made it possible for rapidly growing numbers ofpeople to think about themselves and relate themselves to others, in profoundly newways (Anderson, 1983, p. 40). This appears to be the case for Redwood Estate. Withthe constant influx of residents, the newsletters were an important mechanism insymbolising social cohesion, projecting social norms and reinforcing communityvalues. In the absence of affective relationships and strong social networks amongthe participants in Redwood Estate, the newsletters maintained an imagery ofcommunity life that resonated strongly with the urban village model.

The presentation of place in Redwood Estate was also important in generatingshared values. However, through the interviews with residents and key informants,maintaining community presentation was not instigated at the grass roots level, butwas generated and maintained by the developers through building covenants, limit-ing the number of rental properties and providing cash incentives to residents toenable the landscaping of mature flora. When talking about the annual Spring Fairat Redwood Estate, Ross (who worked for the developer) pointed to the effectlandscaping would have on developing cohesion, pride and even crime prevention:

We do the Spring Fair each year, where we try to have a garden competition andhand out the prizes of the garden competition. Now, theres two things in that. We doit to make our gardens look great and it gives people a sense of pride and to geteveryone aware that Springs in the air, make it look good, give them a sense ofownership and pride of their area and so they take the positive, proactive steps inlooking after their environment rather than letting the crime slip in and then theyvegot to be reactive.

434

REBECCA L. WICKES

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

While residents were aware of the developers role in creating and maintainingan image of community, the participants in this study did not consciously connectthe actions of the developer with their perceptions of community cohesion.Attributions of pride and a shared desire to create a beautiful community werelargely ascribed to the residents. From the visual presentation of the community,people sensed a commonality. The mature trees, the manicured lawns, the limitednumber of renters were visible representations of shared values. From these repre-sentations, the participants in this study perceived others as having a strong sense ofpride and viewed the community having similar values and aspirations, asevidenced in the following passages by Redwood residents:

Linda: I suppose if youre thinking of Redwood specifically, it looks alike, its welllandscaped so I guess theres that kind of feeling of connection or some sort of similar-ity between the people who live there.

David: Its that sort of environment Its got pride in the community, its welllandscaped, its a nice place to live, its nice people, its just probably everything thatmost people are looking for in the place that they call home. Everybody has a sense ofpride everybodys trying to make that place much better.

In contrast to Redwood Estate, there were no community newsletters in HiddenValley to provide residents with information on local issues, nor was there anabundance of community events or community groups. Instead, cohesion wasassumed from the demographic profile of the area. Nearly all residents interviewedin Hidden Valley were aware of the affluent status of their community and believedpeople living in the area were powerful people. As Gus commented: I think a lot ofthat has to do with reasonable affluence. And the reasonably high standard ofeducation that most of the people here have.

Ryan was also well aware of the affluence, describing his fellow residents as well-oiled. He noted the levels of education and professionalism present in the commu-nity, quoting the latest census statistics:

The highest percentages of personal computers for the whole of Australia is inHidden Valley and I thought, hmmm, if thats the case that means that theyrepredominantly professional people but what it also means is professional peopleare going to have professional children.

The participants in Hidden Valley attributed the shared values of fellow residents tothe financial health of the community. Despite the lack of intracommunity relation-ships, people felt that they could trust fellow residents to act in their best interests,as they saw their interests closely aligned.

For many of the residents, affluence and education symbolised work ethic,honesty, competency and power. Collective affluence rather than the presence ofstrong social relationships therefore symbolised collective identity and collectiveefficacy. In the collective efficacy literature, affluence is theoretically relevant tounderstanding the activation of social control, regardless of dense social ties(Morenoff et al., 2001, p. 528). From the accounts of the residents, commonalitywas assumed through the socioeconomic standing of the community. Morality, toler-ance, shared interests and common pursuits were largely assumed and attributable tothe levels of education and wealth in Hidden Valley.

435

COLLECTIVE EFFICACY IN CONTEXT

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

Maintaining Order: Problems and ProcessesThe third aim of this article was to explore the agency of residents in collectivelyefficacious community, especially as it related to crime prevention and maintainingorder. Collective efficacy, as it is defined in the literature exists relative to specifictasks such as maintaining public order (Morenoff et al., 2001, p. 521) and repre-sents the active sense of engagement on the part of residents (Sampson, 2006, p.155). For Sampson and his colleagues (Morenoff et al., 2001; Sampson, 1999, 2002,2006; Sampson et al., 1999) this is the key difference separating collective efficacytheory from other systemic approaches. In the present research, residents had anactive sense of engagement, but their actual engagement was limited.

In both communities residents were asked to specify the most salient problemsfacing the collective and to indicate their level of concern associated with theseproblems. In Hidden Valley, residents commented on the increased traffic, thecontinuing urbanisation of semirural areas and threats to local wildlife as keyproblems facing the collective, but none were overly concerned with these issues.When asked to report on the prevalence of crime, all interviewees believed crimewas very rare in their community.

The problems in Redwood Estate differed from Hidden Valley. Interestingly,despite the high crime incident rate, residents in Redwood Estate did not mentioncrime as a pressing problem. The problems mentioned by residents were the lack ofinfrastructure for young people and their lack of parental supervision. The behav-iour of young people was not framed in terms of deviance per se, but was discussedprimarily in terms of parents failure to supervise their children and the lack of thedevelopers foresight in providing sufficient and appropriate recreational outlets forteenagers. Although most residents mentioned the problem with young people, onlytwo people recounted an actual experience or incident that directly influenced thisperception. The awareness of the problem with young people was primarily derivedfrom reports or accounts of these issues in The Redwood Messenger.

Hidden Valley: A Case of Cumulative Efficacy?Hidden Valley had the second highest collective efficacy score in the CCS sample.It also had very low crime. Yet there was no Neighbourhood Watch or any othercommunity group concerned with crime prevention. None of the residents wereable to provide concrete examples of community-oriented crime prevention efforts.There was also limited evidence of informal surveillance among neighbours. Iinquired if immediate neighbours watched over each others homes or if they kept alook-out for strangers or people who might not have a legitimate purpose in thecommunity. Many of the residents believed that immediate neighbours wouldcertainly take on this role if they were asked. However, only one participant hadpreviously asked neighbours to watch over their home when they were away.

From the interviews, the shared belief in a neighbourhoods conjoint capabilityfor action to achieve an intended effect (Sampson, 2001, p. 95) was primarily basedupon residents own skills, resources and extralocal connections. A belief in thecommunitys capacity to deal with crime and disorder was not derived from previousexperience of collective responses to task-specific problems. The reported collectiveefficacy in Hidden Valley did not depict an activated process associated with crime

436

REBECCA L. WICKES

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

prevention or informal surveillance. Roslyn, the local councillor, regarded people inHidden Valley as highly skilled and well resourced, and capable of responding to alocal problem if it were in their interest, yet she could not think of any example ofprevious collaboration. When a problem arose in Hidden Valley, Roslyn was thefirst person to know about it. She advised that Hidden Valley residents believed shewas there to do their work for them theyre busy and its up to me or somebodyelse to look after all the little problems for them. The demands on her time toattend to seemingly insignificant problems prevented Roslyn from dealing with thebigger political problems she was elected to address. She believed this overrelianceon political structures is particularly prevalent in affluent areas, stemming from amentality that, you know, somebody else should do everything for them. Incontrast to the new parochialism found in the Beltway case (Carr, 2003) there wasno evidence of residents and organisations collaboratively responding to local issuesin Hidden Valley. Baumgartners (1988) research sheds some light on why thismight be as she suggests that residents hesitancy to exercise social control whenfaced with a problem is not driven by their desire to outsource such duties.Suburban residents do not want to jeopardise the image of civility and harmonythat defines the middle-class/affluent suburb by direct confrontation. When viewedthis way, it is possible that residents relied strongly on the local councillor to attendto local problems to safeguard the sense of community felt in this area.

In Hidden Valley, repeated interactions with fellow community residents did notgenerate or sustain collective efficacy, nor was it established from past experienceswhere the community came together to solve a collective problem. Hidden Valleywas not a collectively efficacious community in the true sense, but could be betterdescribed as cumulatively efficacious. When problems did arise, residents, as a rule,did not work together to find a solution but relied on political connections andprocesses to get the job done. The stocks of resources and connections with exoge-nous institutions accounted for the high levels of collective efficacy. In the contextof Hidden Valley, community regulation was dependent on the level of public,rather than private or parochial control in the area.

Collective Efficacy in Redwood: A Conjoint Belief in the DeveloperThe developers of Redwood Estate wanted to create a sense of psychological belong-ing and wellbeing for both present and future residents. One way of achieving thatwas through the layout of the estate. The artificial lakes, the walking trails and theplanting of mature trees encouraged the use of public spaces and created a feeling ofcommunity. For Ross, who worked for the developer, our brand, what we are selling,it is everything to us. The developers considered it important to maintain an imagepromoting a safe and secure residential estate. Security and safety were prominentmessages in Redwood Estates promotional material, and to acknowledge crimeproblems would pose a threat to the success of further developments in the estate.In my meeting with Ross, I specifically asked him to comment on the crime inRedwood. Despite his close connections with the security company and the localpolice constable, his response was, There are definitely no crime problems. Thereare no security issues and we have a less-than-normal issue for teenagers. From therate of crime incidents reported to the police, this was not the case.

437

COLLECTIVE EFFICACY IN CONTEXT

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

The developers, through their connections with the police and the securitycompany, made sure that signs of physical disorder, such as vandalism and graffitiwere removed immediately. As Ross advised,

if there is any vandalism or any graffiti on walls, we pay to get rid of that within 24hours so it doesnt get seen to be a problem we jump on it, it is like quick, quick,get the guys out there today.

Ross informed me that they provide 24-hour security for residents in RedwoodEstate, fund the position of the local constable (including his residence located inthe heart of the estate) and the Neighbourhood Watch program. When residentsmove into the estate, they are provided with the contact names and numbers of allthe key players in Redwood, and are encouraged to contact the relevant institutionin the first instance should a problem of any kind arise.

With the resources provided by the developer, it was no surprise to find thatresidents in Redwood Estate had no direct experience in working collaborativelywith other residents to deal with local problems. The developers in Redwood Estategenerated the belief in the communitys capacity to respond to local problems. Noone in Redwood Estate provided an example of the active sense of engagement onthe part of residents (Sampson, 2006, p. 155) without referring to the engagementof the developer, the security company and the local police constable. Tom, a localresident, believed that the police constable and the security company could handleany problem. Although he had never had to call upon their services, he was certainhe could rely on them in a time of need because there is a lot of police patrol, as Isaid, there is a police beat two streets away from here. If theyre ever called, theywould respond quickly. In our 48-minute interview, Richard, another Redwoodresident, referred to the capacity of the local police constable 14 times.

Not only did residents know that they could rely on formal structures to addresslocal problems, many saw the responsibility for civic or criminal matters as belong-ing to the developers and the police. This was especially true for crime. Davidbelieved the community had a responsibility to deal with issues, only up to apoint. Ian took a similar position and advised that he would be reluctant to getdirectly involved in a criminal matter, and believed other people in the estate feltthe same way.

However, one could make the argument that the residents in Redwood Estatedid intervene on particular problems. When a local problem arose, they contactedthe relevant institution and demanded action. Their belief that they lived in acollectively efficacious community was largely the result of organisation practice.There was little evidence of agency among residents as problems were not resolvedthrough active collaboration. Rather, local problems were referred to the appropri-ate organisation with an expectation that they would be dealt with swiftly andcompetently. The reliance on mechanisms of formal social control was very strongand the action of key institutions provided residents with a belief in the conjointcapability of organisations like the developers and police to address threats to thecommunity. Community self-regulation was not achieved through the efforts ofresidents, but through the actions of formal organisations. Thus the level of publiccontrol in this community was central to perceptions of collective efficacy.

438

REBECCA L. WICKES

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

SummaryThe goal of this article was to qualitatively explore aspects of community thatpromote collective efficacy and the following claims stemming from the collectiveefficacy literature were examined in two collectively efficacious communities: (1)that the urban village model no longer characterised contemporary communities,(2) that communities with weak ties can be effective units of social control and (3)that collective efficacy represents task-specific processes that speak to the agencyof local residents. Drawing on the interview accounts of residents and key infor-mants in two collectively efficacious communities, there was mixed support forthese claims.

Regarding the importance of community, residents in both research sites definedcommunity in terms of relationships, shared values and common interests and inboth locales, the community concept was very strong. The rhetoric often associatedwith an urban village model of community guided the way community was imagedby residents. However, in line with Sampson and his colleagues research andcontrary to the systemic model of community organisation, strong intracommunitynetworks did not form the basis for residents understanding of community life. InHidden Valley and Redwood Estate, social relationships were limited in bothdensity and form, characterised by instrumentality and, in and of themselves, didnot drive perceptions of community cohesion or capacity. How the community wasimagined shaped and structured the expectations and attitudes among residents.While traditional conceptualisations of community may be outdated, in the imagi-nation of community residents, they remain a powerful normative force. Theattachment to the notion of an urban village was what mattered most for percep-tions of cohesion and capacity in this study. This is something not previouslyconsidered in the extant collective efficacy research.

One of the limitations of collective efficacy theory, as it is conceptualised incriminology, is its inability to explain how a collective identity is maintained in theabsence of strong ties and social relationships. The interview accounts of residentsand key informants in Hidden Valley and Redwood Estate go some way in address-ing this. In both communities, a collective identity was largely assumed through thecollective and symbolic representations of community life. A sense of cohesion andperceptions associated with shared values was symbolised through newsletters, thepresentation of physical space and the presumed socioeconomic standing of fellowresidents. For example, in Redwood Estate, a shared identity was manufacturedthrough the local newsletters, the Redwood branding and aesthetics created andmaintained by the developer. Many of the residents believed they lived amonglike-minded people, however, their shared values and commonality were assumedand derived from manufactured symbols and representations of community life. Thiswas also the case in Hidden Valley. In the absence of developers, newsletters andcommunity functions, a collective identity was garnered through symbols of success.Morality, family values and responsibility for collective action were assumed charac-teristics of people who lived in this area, with affluence and education playing alarge role in the participants accounts of community cohesion and commonality.

Durkheim (1915[1912]) suggested that collective representations provide a wayin which one can study how culture or society (or, in Durkheims case, religion)

439

COLLECTIVE EFFICACY IN CONTEXT

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

becomes established in the minds of the collective. Understanding the collectiverepresentations associated with perceptions of community organisation is a crucialcomponent in explaining the variation of crime across loosely connected communi-ties. Examining the salient symbols associated with generating a culture of trust andshared values can enhance our understanding of collective efficacy in contempo-rary urban settings where strong ties are few, collective membership is voluntaryand interests are diffuse and often conflicting. In the case of Redwood Estate,perceptions of collective efficacy were high in spite of the high crime ratesreported in this area. This was largely due to the invisibility of the incivilities andvisibility of symbols of cohesion and social order, all of which were largely main -tained by the developer.

The final goal of this article was to examine the agentic claims present in collec-tive efficacy theory. Despite the high levels of reported collective efficacy inRedwood Estate and Hidden Valley, the active engagement of residents was absent.The majority of interviewees had no knowledge of past or present collaboration onan identifiable task associated with crime control or crime prevention. In contrast,local organisations and institutions were very active in both areas. In RedwoodEstate, in particular, they were crucial in maintaining community regulation andsocial control. The appropriate organisations in Redwood Estate handled problemsfor residents. The developer dealt with civic matters, and the local police constableor the security company handled problems with crime or disorder. In Hidden Valley,civic issues and even low-level neighbourly annoyances were commonly directed tothe local councillor. Residents did not take a direct and proactive approach tocommunity regulation. In the present research, the agency or the collective-actionorientation of residents (Sampson, 2006, p. 154) was dependent upon the actionsor the orientations of key institutions. Like Bursik and Grasmick (1993) and Carr(2003), the present research points to the need for future research to consider thebehaviour of institutions or at a minimum, the perceptions of institutional capacityas opposed to concentrating on the presence of organisations or community groups.

Sampson and his colleagues are certainly correct in their call to move beyond afocus on social ties and networks when explaining the variation of crime and disor-der across the urban landscape. However, the results of this study suggest the keytenets of collective efficacy require further consideration. While community regula-tion may not require dense, interlocking networks, a strong belief in the communityconcept could be the main driver of resident perceptions of collective efficacy.Moreover, from the accounts of residents and key informants in the presentresearch, stocks of networks and resources are important in the development andmaintenance of collective efficacy. In the two communities studied herewith, theywere strongly linked to perceptions of trust, cohesion, shared values and a perceivedcapacity to respond to crime, regardless of the absolute level of crime in the area. Todate, connections to institutions and the availability of public social control arenot fully considered in the extant collective efficacy research. As these findingshighlight and as others have previously argued (see Bursik & Grasmick, 1993; Carr,2003), the ability to leverage local and extra local resources and the behaviour ofcommunity institutions are key features of community regulation. In sum, althoughcollective efficacy might be the most proximate mechanism in preventing crime

440

REBECCA L. WICKES

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

and while it can exist without dense, intracommunity networks, the mechanismsthat generate and sustain collective efficacy require further exploration.

Endnotes1 An SLA is a general purpose spatial unit that is used to collect and disseminate statistics. In

some instances the SLA is a geographic representation of one suburb, but can also comprisetwo or more suburbs (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2001) as was the case in the CCS sample.The population of the SLAs in the BSD range from 263 to 65,694 residents

2 Pseudonyms are used in this article to preserve the anonymity of the respondents and keyinformants

ReferencesAnderson, B. (1983). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism.

London: Verso.Anderson, E. (1990). Streetwise: Race, class and change in an urban community. Chicago: University

of Chicago Press.Anderson, E. (1999). Code of the street: Decency, violence and the moral life of the inner city. New

York, W.W. Norton.Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2001). Community profiles for Brisbane Statistical Division. Retrieved

November 20, 2005, from www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]//web+pages/Census+DataBandura, A. (1995). Self-efficacy in changing communities. New York: Cambridge University Press.Bandura, A. (1997). The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman.Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology,

52(1), 126.Bauman, Z. (2001). Community. Cambridge: Polity.Baumgartner, M.P. (1988). The moral order of a suburb. New York: Oxford.Bursik, R.J. (1988). Social disorganization and theories of crime and delinquency: Problems and

prospects. Criminology, 26, 519552.Bursik, R.J., & Grasmick, H.G. (1993). Neighborhoods and crime: The dimensions of effective commu-

nity control. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.Carr, P J. (2003). The new parochialism: The implications of the Beltway case for arguments

concerning informal social control. American Journal of Sociology, 108, 1491291.Coleman, J.S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of

Sociology, 94, S95-S120.Day, G. (2006). Community and everyday life. London: Routledge.Drukker, M., Kaplan, C., Feron, F., & van Os, J. (2003). Childrens health-related quality of life,

neighborhood deprivation and social capital: A contextual analysis. Social Science andMedicine, 57, 825841.

Durkheim, E. (1912). The elementary forms of the religious life. London: Allen & Unwin.Flick, U. (1998). An introduction to qualitative research: Theory, method and applications. London:

Sage.Gans, H.J. (1967). The Levittowners. London: Allen Lane The Penguin PressGibson, C.L, Zhao, J., Lovrich, N.P. ,& Gaffney, M.J. (2002). Social integration, individual

perceptions of collective efficacy, and fear of crime in three cities. Justice Quarterly, 19(3),537564.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity. Cambridge: Polity Press.Girling, E., Loader, I., & Sparks, R. (2000). Crime and social change in middle England: Questions of

order in an English town. London: Routledge.

441

COLLECTIVE EFFICACY IN CONTEXT

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

Hendryx, M., & Ahern, M. (2001). Access to mental health services and health sector socialcapital. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 28(3), 205218.

Houston, M.J., & Sudman, S. (1975). A methodological assessment of the use of key informants.Social Science Research, 4(2), 151164.

Hunter, A.J. (1985). Private, parochial and public school orders: The problem of crime and incivil-ity in urban communities. In G.D.Suttles & N.Z. Mayer (Eds.), The challenge of social control:Citizenship and institution building in modern society (pp. 230242). Norwood, NJ: AblexPublishing.

Israel, G.D., Beaulieu, L.J., & Hartless, G. (2001). The influence of family and community socialcapital on educational achievement. Rural Sociology, 66(1), 4368.

Kawachi, I., Kennedy, B.P., Lochner, I., & Prothrow Stith, D. (1997). Social capital, incomeinequality and mortality. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 14911498.

Kennedy, B.P., Kawachi, I., Prothrow-Stith, D., Lochner, K., & Gupta, V. (1998). Social capital,income inequality and firearm violent crime. Social Science & Medicine, 47, 117.

Kornhauser, R. (1979). Social sources of delinquency: An appraisal of analytic models. Chicago:University of Chicago Press.

Krannich, R.S., & Humphrey, C.R. (1986). Using key informant data in comparative communityresearch: An empirical assessment. Sociological Methods and Research 14(4), 473493.

Kreps, G.M, Donnermeyer, J.F., Hurst, C., Blair, R., & Kreps, M. (1997). The impact of tourism onthe Amish subculture: A case study. Community Development Journal 32(4), 354367.

Mason, J. (1996). Qualitative researching. London: Sage Publications.Mazerolle, L., Wickes, R.L., & McBroom, J. (in press). Community variations in violence: The

role of social ties and collective efficacy in comparative context. Journal for Research in Crimeand Delinquency.

Morenoff, J., Sampson, R.J., & Raudenbush, S. (2001). Neighborhood inequality, collectiveefficacy and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology, 39, 517560.

Noguera, P.A. (2001). Transforming urban schools through investments in the social capital ofparents. In Saegert, S., Thompson, J.P. & Warren M.R. (Eds.), Social capital and poor communi-ties (pp.189212). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Nuehring, E.M., & Raybin, L. (1986). Mentally ill offenders in community based programs:Attitudes of service providers. Journal of Offender Counselling, Services and Rehabilitation, 11(1),1937.

Neuman, W.L. (2006). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Boston, MA:Allyn & Bacon.

Oberwittler, D., & Wikstrom, P.O. (2006, November). Behavior contexts and victimisation. Paperpresented to the American Society of Criminology 58th Annual Meeting, Los Angeles, CA.

Pattillio, M.E. (1998). Sweet mothers and gangbangers: Managing crime in a black middle-classneighborhood. Social Forces, 76, 747774.

Pawson, R. (1996). Theorizing the interview. The British Journal of Sociology, 47(2), 295314.Raudenbush, S.W., & Sampson, R.J. (1999). Ecometrics: Toward a science of assessing ecological

settings, with application to the systematic social observation of neighborhoods. SociologicalMethodology, 29, 141.

Sampson, R.J. (1988). Local friendship ties and community attachment in mass society: A multi-level systemic model. American Sociological Review, 53, 766779.

Sampson, R.J. (1999). What community supplies. In R.F. Ferguson & W.T. Dickens (Eds.),Urban problems and community development (pp. 241292). Washington: The BrookingsInstitution.

Sampson, R.J. (2001). Crime and public safety: Insights from community-level perspectives onsocial capital. In S. Saegert, J.P. Thompson, & M.R. Warren (Eds.), Social capital and poorcommunities (pp.189212). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

442

REBECCA L. WICKES

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

-

Sampson, R.J. (2002). Transcending tradition: New directions in community research, Chicagostyle. Criminology, 40(2), 213230.

Sampson, R.J. (2006). Collective efficacy theory: Lessons learned and directions for future inquiry.In F.T. Cullen, J.P. Wright, & K. Blevins (Eds.), Taking stock: The status of criminological theory(Advances in Criminological Theory), Vol. 15, 149167.

Sampson, R.J., & Groves, B. (1989). Community structure and crime: Testing social-disorganiza-tion theory, American Journal of Sociology, 94, 774802.

Sampson R.J., Morenoff, J., & Earls, F. (1999). Beyond social capital: Spatial dynamics of collec-tive efficacy for children. American Sociological Review, 64, 633660.

Sampson, R.J., Raudenbush, S.W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multi-level study of collective efficacy. Science, 277, 918924.

Sampson, R.J., & Wikstrom, P.O. (2004, Wikstrm, P.O. (2006, ). The social order of violence. InChicago and Stockholm neighborhoods: A comparative inquiry. Paper presented at the conferenceon Order, Conflict, and Violence, Yale University.

Shaw, C.R., & McKay, H.D. (1931/1999). Selection from National Commission on LawObservance and Enforcement Vol.II. In F.R. Scarpitti & A.L. Neilsen (Eds.), Crime and crimi-nals: Contemporary and classic readings (pp. 284297). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury PublishingCompany.

Skogan, W. (1986). Fear of crime and neighborhood change. In A.J. Reiss, & M. Tonry, (Eds.),Communities and crime (pp. 203230). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Skogan, W. (1989). Communities, crime and neighborhood organisation. Crime & Delinquency, 35(3), 437457.

Skogan, W. (1990). Disorder and decline: Crime and the spiral of decay in American neighborhoods.New York: The Free Press.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1997). Grounded theory in practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Tonnies, F. (1955). Community and association. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. (Original work

published 1887).Wellman, B. (1999). Networks in a global village. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.Wikstrm, P.O. (2006, November). Activity fields and setting. Theorizing and studying the role of

behavior. Paper presented to the American Society of Criminology 58th Annual Meeting, LosAngeles, CA.

Wilson, W.J. (1987). The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass and public policy. Chicago:University of Chicago Press.

Wilson, W.J. (1996). When work disappears: The world of the new urban poor. New York: VintageBooks.

443

COLLECTIVE EFFICACY IN CONTEXT

THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY

by cursuri psihologie on October 11, 2012anj.sagepub.comDownloaded from