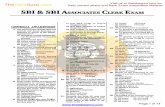

40 YEARS AGOAND NOW SBI and the big bank theory

Transcript of 40 YEARS AGOAND NOW SBI and the big bank theory

PRIYANAIR

State Bank of India (SBI) isIndia’s biggest bank and prob-ably one of the country’s most

enduring brand names. It has abranch network of 16,801, an ATMnetwork of 53,871 (including those of associate banks), about 200,000employees and is banker to mil-lions of Indians. Over the years,and especially in the 70s when the government of India strength-ened its hold on the banking system, it became a trend-setter among nationalised banks inintroducing products and services,and bankrolling some of India’slargest industrial projects.

“We have been partners innation building and take our rolein building the nation very proud-ly. We have played our part e�-ciently,” says ArundhatiBhattacharya, chairman and the�rst woman to head the bank.

However when it comes toGen-Next, SBI does not appear aspirational enough, asBhattacharya admits. That is large-ly due to issues on service delivery,which the bank is working on.

As a signature bank withantecedents that stretch back tocolonial India (SBI grew out of theImperial Bank of India), SBI repre-sented both the upside and down-side of public sector banking.Today, it faces considerable com-petition from smaller, leaner andnimbler private competitors, but40 years ago, there was no doubtthat it bestrode the Indian bankingworld like a colossus.

It was in the 70s that the bankdivided its business based on cus-tomer segments. These comprisedpersonal banking, small scalebanking, large corporate banking,agriculture banking and interna-tional banking. Divisions were cre-ated in branches under branchmanagers. Depending on the busi-ness volume, some branches hadtwo or three divisions, while someof the bigger ones had all the divi-sions. This made it easy for cus-tomers to conduct their transac-tions, since each divisionfunctioned like a standalonebranch.

Another �rst by SBI was settingup full-�edged specialised branch-es to cater to di�erent customer

segments, such as per-sonal banking branches,non-residential Indianbranches, large corpo-rate branches, branchesfor high net worth indi-viduals and so on.

SBI was also the �rstto bifurcate its lendingbooks into large corpo-rate, mid-corporate,small and mediumenterprises and so on. “We wereable to devise products catering tothe di�erent segments,”Bhattacharya says.

The �rst agriculture develop-ment branch was set up in Palakkaddistrict, in Kerala, also in the 70s.The bank focused on agriculture ina big way since that was the need ofthe country at that time.

In the 80s, SBI started classify-ing some sticky loans as non-per-forming assets (NPAs) and beganprovisioning for these. In the mid-’90s, SBI started giving creditscores for corporate loans based on the balance sheet of the com-

panies and o�ering dif-ferential rates.Corporations thatreceived a high ratingwere given loans atmarginally lower ratesthan others. Later, itbecame mandatory forbanks to follow thecredit ratings given byspecialised agenciessuch as CRISIL before

sanctioning loans.In the early 2000s, SBI started

the centralised processing of loans,thereby making branches onlydelivery channels for acceptingloan applications. Loan proposalswere processed at the centralo�ces or zonal o�ces. Thisensured faster sanctioning anddisbursal of loans. It also did awaywith the need to have personnelwho were experts in credit apprais-al at the branches. Branch sta� wasfreed up for marketing and couldbe deployed to source business.

In the late 90s, SBI was amongthe �rst nationalised banks to o�er

consumer durable loans. Thesewere loans for television, personalcomputers and other electronicitems. It was also among the �rst too�er credit cards, through its jointventure with GE. It was also the�rst, and probably is still the onlyone, to o�er gold deposit scheme,where customers can deposit theirgold with the bank and earn inter-est on it.

It also successfully made itspresence felt in the auto loan seg-ment, aggressively tying up withauto manufacturers and dealers too�er on the quick loans at lowrates. As on September 2014, SBI

had a portfolio of ~1,48,502 crorehome loan and an auto loan port-folio of ~28,879 crore.

Nationalised banks, however,woke up to the growth potential inthe retail home loan segment onlyafter private sector peers. Evenamong public sector banks, SBI wasslow to catch on to the trend, admitformer o�cials. Under the tenureof O P Bhatt, it introduced severalinnovations in the home loan seg-ment, which helped it increase itsmarket share. For instance, theteaser �xed-cum-�oating ratehome loans were �rst launched bySBI around 2009. Several otherbanks and housing �nance com-panies followed the example andcame out with their own versions.

These loans had a �xed rate for the�rst two to �ve years after whichthey became �oating rate loans.But the product came for criticismfrom the regulator on the groundsthat it was misleading customers.So, banks, including SBI, had to dis-continue these.

Thanks to its wide network and customer base, it has accessto a huge amount of low costdeposits. This allows it to retailloans at low rates and garner mar-ket share.

Despite being a nationalisedbank, SBI has matched its youngerand more tech-savvy private sectorpeers in issuance of debit cards,setting up point-of-sales terminalsand ATMs. Some of its innovationsinclude drive-through ATMs and �oating ATMs, an attemptmake these available even inremote locations. According to theSBI website, as on June, the bankhas a 22 per cent market share indebit card spends over POS and e-commerce.

It has also made huge stridesin internet and mobile banking.As on September, the bank had1.99 crore internet banking usersand 1.15 crore mobile bankingusers.

“We see huge amounts of trans-actions through our internet andmobile banking platforms. We alsohave a tie-up with Flipkart for ourdebit card and we saw a hugeamount of e-commerce throughour website,” Bhattacharya says.

The bank also has a robustkiosk model to cater to the ruralbanking segment. For sta� train-ing, the bank uses an electronicplatform which can support10,000 users at a time.

When the sectors like assetmanagement and insurance sectorswere opened, SBI took the oppor-tunity to diversify its. It set up theasset management SBI MutualFund in 1987, the life insurance sub-sidiary in 2001 and the generalinsurance subsidiary in 2008.

“We are present in all areasand our products are the best.Even in digital technology, ouro�erings are ahead of time. Wewant to better this. The questionis how to motivate our sta� too�er better customer service. Itis due to this that delivery of serv-ices seems to be a problem,” saysBhattacharya. As SBI readies forthe next 40 years in an era ofnano-second banking, this mightbe its biggest challenge yet.

Despite taking the initiative in several areas, the country’s biggest bank does not meet theaspirational needs of the younger generation. Work is on to change this

SBI and the big bank theory40 YEARS AGO...AND NOW

“The question is how tomotivate our sta� to o�erbetter services. It is due tothis that delivery of servicesseems to be a problem”

ARUNDHATI BHATTACHARYASBI chairman and the �rst woman tohead the bank

SOURCE: http://www.business-standard.com/article/pf/40-years-ago-and-now-sbi-and-the-big-bank-theory-114122800724_1.html

29-12-2014, PAGE 9