246 TUGboat,Volume29(2008),No

Transcript of 246 TUGboat,Volume29(2008),No

246 TUGboat, Volume 29 (2008), No. 2

Designing and producing a referencebook with LATEX: The Engineer’s QuickReference Handbook

Claudio Beccari and Andrea Guadagni

AbstractThis article describes the process of designing anItalian reference book, namely Il prontuario dell’in-gegnere. As a reference work it shares the char-acteristics of any other such book; it also uses alarge amount of mathematics and contains a largenumber of graphics insertions. Moreover, the pub-lisher wanted to distribute the work both as a reg-ular bound book and as a computer file to be readdirectly on the computer screen.

1 IntroductionIn the first half of the nineties, Andrea Guadagni(AG) asked Claudio Beccari (CB) to collaborate onthe production of a ‘Quick Reference’ handbook, in athinner and more comfortable format than the his-torical and bulky landmark volume for engineers,the Manuale dell’ingegnere (The Engineer’s Hand-book) by Colombo1 [2]. This Quick Reference hand-book was planned to be published at the publishingcompany Hoepli, well-known in Italy for its collec-tion of handbooks in every possible discipline. Thegeneral idea was that the Quick Reference shouldbe a collection of records, each one on a particularsubject, with a minimum of mathematics, prefer-ably self-contained and without reference to otherrecords.

As the editor of the huge “Manuale”, AG hadall the necessary experience for finding the experts,for organising the material to be published, and formanaging the whole publishing process. Eventuallyhe also took care of the source file editing.

On the other side, CB already had some experi-ence with LATEX design and layout, but the produc-tion of the “Quick Reference” was a new challengethat required a very close interaction between AGand CB.

Editor’s note: This is a translation of the article “La pro-gettazione di un’opera di consultazione: l’edizione del Pron-tuario dell’ingegnere con LATEX”, which first appeared inArsTEXnica issue #4 (October 2007), pp. 16–24. Reprintedwith permission. Translation by the author.

1 Professor Colombo’s first name was Giuseppe, but thehandbook was and still is simply named “Il manuale delColombo” (Colombo’s handbook) or “il Colombo” by everyengineer, no matter the specialization.

2 LATEX in the ninetiesFirst of all it may be useful to mention some ques-tions concerning computers and programming thattoday are obsolete, but at the time were a real prob-lem; mentioning these problems is of general interestin every cooperative work when many authors are in-volved. Moreover, even if advances in the computerworld have eradicated several incompatibilites, oftennew ones arise, producing new problems. It is advis-able that authors who want to produce a coopera-tive document be aware of these problems and knowhow to overcome the difficulties that they might en-counter along their path.

One of the problems was the fact that CB, AGand the various collaborators used different plat-forms. CB was still working with a DOS PC; Win-dows 95 had just appeared but it was not so wide-spread on existing PCs. Windows 3.1 was still toorudimentary for this kind of work, for one thing be-cause its graphic interface used most of the memoryavailable to those PCs. Moreover, CB was still work-ing with LATEX2.09, although by the end of the workLATEX2ε was available; as usual at that time he wasusing a plain ASCII editor and ran the various LATEXconnected applications with suitable command lines.

On the other hand, AG was working with aMacintosh, whose operating system was very differ-ent from the simple DOS from many points of view,not least that paths were described in a very differ-ent way. Obviously it had a beautiful graphic inter-face, but this was more or less irrelevant for the goalof the production of this work. Concerning the TEXsystem, AG was using Textures; this was (and stillis) a commercial product by BlueSky Research andit worked both as an editor and as a synchronouspreviewer, that is, it employs two windows open si-multaneously, in one of which the usual .tex sourceis edited while the other synchronously displays theresult of typesetting at the same rate that text isinput in the editor window.

Today, everything is simpler; plain DOS is al-most forgotten; although the command window al-lows one to use a more modern DOS incarnation,most users appear to ignore its existence. Apple hasrecently changed the operating system of its Macin-toshes, passing to MacOSX, a Unix-based operatingsystem with the typical Macintosh beautiful graphicinterface.

On the TEX system side, the TEX Users Groupand most other TEX user groups distribute the freeTEX system through the TEX Collection CDs andDVDs; TEX Live is available for all platforms and

TUGboat, Volume 29 (2008), No. 2 247

the differences between the various operating sys-tems are managed in a unified way, so that the macrocollections and the packages are more and more plat-form independent.

But in the nineties it was necessary to fightagainst the various ways of indicating absolute andrelative paths: DOS and Unix used the slash / whileMacintosh used the colon :, and in different posi-tions from those where DOS and Unix would use /.This was relevant for the production of the QuickReference handbook, because the subpaths where itwas handy to keep the pictures and other includedmaterial had to be accessed on both systems. Justto give an idea of the code that had to be imple-mented, here are the macros that would automati-cally change the explicit path of a file containing afigure.\newif\if@path \@pathfalse% These macros were adapted from Knuth’s% TeXbook (pag. 375)\def\check@figurefilepath#1{%

\@@chkfpM#1:\@@chkfpM\@%\if@path\else\@@chkfpU#1/\@@chkfpU\@\fi}%\def\@@chkfpM#1:#2#3\@{%

\ifx\@@chkfpM#2\@pathfalse\else\@pathtrue\fi}

\def\@@chkfpU#1/#2#3\@{%\ifx\@@chkfpU#2\@pathfalse\else

\@pathtrue\fi}%% This is the macro that possibly prepends% the path specification to the file name% of a figure, then it checks if the% folder or directory separators agree% with the operating system; eventually it% passes this generated full specification% to the macro that includes the figure.%\parse@figure@filename#1{%\def\figurefilename{#1}%\ifx\def@ultpath\empty\else

\expandafter\check@figurefilepath\expandafter{\figurefilename}%\if@path\else

\edef\figurefilename{%\def@ultpath\ifMacintosh:%

\else/\fi\figurefilename}%\fi

\fi\ifMacintosh

\expandafter\Mac@rename\figurefilename/\relax

\else\expandafter\UNIX@rename

\figurefilename:\relax\fi}

%% Recursive macro that erases the slashes% and sets the colons.%\def\Mac@rename#1/#2\relax{%

\def\@tempA{#2}%\ifx\@tempA\empty

\def\figurefilename{#1}%\else

\def\@tempA{#1:#2}%\expandafter\remove@slash

\@tempA\relax\expandafter\Mac@rename

\figurefilename/\relax\fi}

%% Recursive macro that erases the colons% and sets the slashes.%\def\UNIX@rename#1:#2\relax{%

\def\@tempA{#2}%\ifx\@tempA\empty

\def\figurefilename{#1}\else\def\@tempA{#1/#2}%\expandafter\remove@colon

\@tempA\relax\expandafter\UNIX@rename

\figurefilename:\relax\fi}

%% These macros erase the final slash% or colon.%\def\remove@slash#1/\relax{%

\def\figurefilename{#1}}\def\remove@colon#1:\relax{%

\def\figurefilename{#1}}

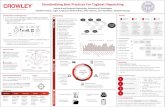

3 The layout of the bookFor the typeset book AG and CB agreed on a layoutwhere each record would be a freestanding sectionto be introduced with \section. Furthermore, eachrecord should consist of a single spread: in the ‘pa-per’ version of the book, where pages are turnedfrom right to left, it was necessary that the writ-ten part be typeset on an odd page (the recto page)on the right side of the spread, while the graphiccontents of the record would appear on the versoof the previous sheet, an even page, i.e. on the leftpart of the spread. The sections were collected inchapters, and the latter in parts. Each part dealtwith a particular branch of engineering, for examplethe part “Edilizia” (Building) would be divided inthe chapters dealing with such chapters as “Founda-tions”, “Pillars”, “Roofs”, and the like; each chaptercontained a few records concerning the details, withformulas, tables, drawings, descriptions, costs, etc.

248 TUGboat, Volume 29 (2008), No. 2

The publishing house wanted also an “e-book”version of this reference book; in this electronic ver-sion, where pages scroll from bottom to top, butreading goes from left to right, the record shouldoccupy a single screen, with the written part on theleft and the graphic part on the right.

Both versions have thumbnails on the side ofthe page. In the paper version traditionally it wouldhave been necessary to make a semicircular cut inthe pages, as sometimes seen in large Holy Books, orin large dictionaries or encyclopedias. However, thehigh cost of this operation suggested we use a sim-pler method, namely to let the thumbnail shadowbe visible on the external margin cut, by typeset-ting such thumbnails across the trimming area.

The electronic version had all the necessary in-ternal links, but for consistency with the printedversion it also contained various icons (thumbnails)on the left side.

Headers, footers, part titles, records, the tableof contents and the index required a particular lay-out, partly because each page, each contents entry,and each chapter required the name of the individualauthor or the name of the chapter coordinator.

The source files for both the printed and theelectronic version had to be identical and the outputformat chosen with a single option in the main file.

4 Page layout and fontsThe trimmed page size was a standard ISO-A5, thatis, 148mm by 210mm. The main text box, withoutheaders and footers, was 116mm by 175mm. Withsuch a compact text box, we decided to typeset thebook with fonts of size 9/10 pt; we left the decisionon the font collection to a later time, after attentiveexamination of the typesetting results with differenttypefaces. We eventually chose the Times fonts, be-cause with Textures (at that time) they were easierto configure and use.

Figure 1 shows a spread of the printed version:the left page contains the drawings relative to therecord or section, while the right page displays thetext and the other relevant information. The thumb-nail icon that characterizes the part [in the example:“Edilizia” (Building)] is on the right page. The parttitle is repeated on the left header, while the chaptertitle is only in the right header. The section title iscentered above the text. The record is subdividedinto small unnumbered subsections in line with thetext. The section author is in the right footer whilethe left footer contains the book title and the pub-lisher’s name.

Figure 2 contains in one screen shot more or lessthe same information, except that thumbnails, text

and drawings are interchanged with regard to ‘left’and ‘right’ sides. There is just one header and onefooter, the contents of which are flush to the externalmargins. The rest is identical to the printed version.

While the printed version had pages of size A5that form a spread in a landscape A4, the electronicversion has one screen shot in landscape with a pagesize (needed for the PDF output) of a landscape A4sheet. The typesetting information for LATEX had tobe completely automatic, depending on the versionto be output. If a screen shot had to be printed,either the landscape orientation must be compati-ble with the printer, or the latter should be capa-ble of scaling the printed area to the paper width.This was a necessary warning at that time; today allprinters are capable of printing in landscape mode.

5 LATEX commands for inputting recordsThe LATEX input of this Quick Reference handbookobviously requires specific commands in order tocope with the specific requirements of the layout.

For example, the drawings of each record mustbe separately assembled, possibly with recourse toa graphics editor so as to produce a single graphicobject to be included in the output file. At thosetimes it was absolutely necessary to run LATEX andproduce output in DVI format, then passed throughdvips in order to get the PostScript format, and fi-nally to get the PDF format by running the ps2pdfprogram. Today it would be possible to get the sameresult with one pass through pdflatex. Nevertheless,once suitable macros were made available, it waseasy to get the desired result for both the editorand the individual authors.

The macros for starting a new spread or a newchapter required only the specification of the perti-nent title and the name of the author or editor.

The macros that started a new part had to pro-vide the pointer to the specific thumbnail and to itstypesetting on the proper margin in each version.The option draf had to be modified so that dur-ing the preliminary work the authors and the editorcould save a lot of black ink by omitting printing thethumbnail, but leaving the explicit part title in therelevant margin.

The babel package at that time did not have thefunctionality it has today; in addition many ItalianLATEX users did not even know they could typesetwith the rules of Italian typography and with Ital-ian hyphenation, or they did not know how to con-figure their system; many were still working withLATEX2.09. So we created the necessary tests withsuitable warning messages in order to assure at least

TUGboat, Volume 29 (2008), No. 2 249

2 Edilizia

Prontuario dell’ingegnere – Hoeply

Strutture in calcestruzzo armato 3

Edil

izia

D

PILASTRI

Materiali. Calcestruzzo di buona qualita con una resistenza a rottura dicirca 30 N/mm2 (v. Calcestruzzo, pag. ??). Armature di acciaio ad aderenza mi-gliorata con una resistenza a rottura di circa 440N/mm2 (v.Acciaio, pag. ??)

Carichi. I pilastri sono soggetti alle forze verticali dovute al peso sovrastan-te (carichi permanenti e accidentali). Se l’edificio e in zona sismica i pilastri, letravi e il blocco scale-ascensori devono resistere alle forze orizzontali causate dalterremoto (v. La struttura nel suo complesso, pag. ??). I carichi verticali sono paria circa 10 kN/m2 per ogni piano. Se un pilastro sostiene una soletta di 5m×5m= 25m2, ogni piano contribuisce con 250 kN al carico sul pilastro.

Sezione. Se N e il carico verticale e A la sezione trasversale, σ = N/A ela tensione di esercizio nel calcestruzzo per i carichi verticali. Si sceglie l’area Ain modo che la tensione di esercizio si mantenga inferiore ai valori prescritti. Siha che A = Ac + m As con Ac area del calcestruzzo, As area delle armature em (coefficiente di omogeneizzazione) uguale a 14. Inoltre As ' 0,01 Ac, con unminimo di 4 d 12. (In presenza di carichi orizzontali e necessario tener conto deimomenti flettenti che sollecitano i pilastri.)

Dimensioni in funzione del carico

N Ac a× a a× 25 As

kN cm2 cm×cm cm×cm cm2

250 321 18×18 15×25 4,4500 642 25×25 25×25 6,4750 963 31×31 39×25 9,6

1000 1285 36×36 51×25 12,91250 1606 40×40 64×25 16,11500 1927 44×44 77×25 19,31750 2249 47×47 90×25 22,52000 2570 51×51 103×25 25,7

Forma. Normalmente i pilastri sono rettangolari o quadrati (fig.A, B). Incasi particolari sono a L, a C, a T. Lo spessore dei pilastri che stanno lungo ilcontorno dell’edificio dipende dallo spessore della muratura. Di solito, pero, nonsi scende sotto i 20 cm. Le armature longitudinali vengono disposte negli angoli e,se occorre, lungo i lati della sezione ogni 30 cm circa. Il diametro delle armaturelongitudinali va da 12mm a 20mm e solo eccezionalmente fino a 26 mm. Le staffeseguono il contorno della sezione e sono disposte a un intervallo di circa 15 cm. Ildiametro delle staffe va da 6mm a 10mm. Il copriferro sulle staffe deve essere nonmeno di 2 cm (v.Acciaio, pag. ??).

Dettagli costruttivi. Riprese di armatura da piano a piano (fig.C). Pila-stri di sezione particolare (fig. D). Smussi negli spigoli: e opportuno prevederli di2,5×2,5 cm. Negli edifici in zona sismica le armature dei pilastri e quelle delle travidevono essere opportunamente collegate.

Casseri e getti. Modalita di disposizione dei casseri (fig. E). Modalita digetto: normale ma con particolare cura nella vibrazione. Tempo di maturazione:circa una settimana per tutti i pilastri di un piano.

Quantita e costi. Incidenza delle armature: da 120 a 140 kg di acciaioper m3 di calcestruzzo. Pilastro di 30 cm×40 cm, per piano di altezza 320 cm:calcestruzzo 0,38m3, acciaio 50 kg, casseri 4,5m2. Costo (1998): 300 000 Lit.

Renato Villa

Figure 1: Printed version: a spread.

Edil

izia

D

5 Strutture in calcestruzzo armato

PILASTRI

Materiali. Calcestruzzo di buona qualita con una resistenza a rottura dicirca 30 N/mm2 (v. Calcestruzzo, pag. 11). Armature di acciaio ad aderenza mi-gliorata con una resistenza a rottura di circa 440 N/mm2 (v. Acciaio, pag. 10)

Carichi. I pilastri sono soggetti alle forze verticali dovute al peso sovrastan-te (carichi permanenti e accidentali). Se l’edificio e in zona sismica i pilastri, letravi e il blocco scale-ascensori devono resistere alle forze orizzontali causate dalterremoto (v. La struttura nel suo complesso, pag. 12). I carichi verticali sono paria circa 10 kN/m2 per ogni piano. Se un pilastro sostiene una soletta di 5m×5 m= 25 m2, ogni piano contribuisce con 250 kN al carico sul pilastro.

Sezione. Se N e il carico verticale e A la sezione trasversale, σ = N/A ela tensione di esercizio nel calcestruzzo per i carichi verticali. Si sceglie l’area Ain modo che la tensione di esercizio si mantenga inferiore ai valori prescritti. Siha che A = Ac + m As con Ac area del calcestruzzo, As area delle armature em (coefficiente di omogeneizzazione) uguale a 14. Inoltre As ' 0,01 Ac, con unminimo di 4 d 12. (In presenza di carichi orizzontali e necessario tener conto deimomenti flettenti che sollecitano i pilastri.)

Dimensioni in funzione del carico

N Ac a× a a× 25 As

kN cm2 cm×cm cm×cm cm2

250 321 18×18 15×25 4,4500 642 25×25 25×25 6,4750 963 31×31 39×25 9,6

1000 1285 36×36 51×25 12,91250 1606 40×40 64×25 16,11500 1927 44×44 77×25 19,31750 2249 47×47 90×25 22,52000 2570 51×51 103×25 25,7

Forma. Normalmente i pilastri sono rettangolari o quadrati (fig.A, B). Incasi particolari sono a L, a C, a T. Lo spessore dei pilastri che stanno lungo ilcontorno dell’edificio dipende dallo spessore della muratura. Di solito, pero, nonsi scende sotto i 20 cm. Le armature longitudinali vengono disposte negli angoli e,se occorre, lungo i lati della sezione ogni 30 cm circa. Il diametro delle armaturelongitudinali va da 12mm a 20mm e solo eccezionalmente fino a 26 mm. Le staffeseguono il contorno della sezione e sono disposte a un intervallo di circa 15 cm. Ildiametro delle staffe va da 6mm a 10mm. Il copriferro sulle staffe deve essere nonmeno di 2 cm (v.Acciaio, pag. 10).

Dettagli costruttivi. Riprese di armatura da piano a piano (fig.C). Pila-stri di sezione particolare (fig. D). Smussi negli spigoli: e opportuno prevederli di2,5×2,5 cm. Negli edifici in zona sismica le armature dei pilastri e quelle delle travidevono essere opportunamente collegate.

Casseri e getti. Modalita di disposizione dei casseri (fig. E). Modalita digetto: normale ma con particolare cura nella vibrazione. Tempo di maturazione:circa una settimana per tutti i pilastri di un piano.

Quantita e costi. Incidenza delle armature: da 120 a 140 kg di acciaioper m3 di calcestruzzo. Pilastro di 30 cm×40 cm, per piano di altezza 320 cm:calcestruzzo 0,38m3, acciaio 50 kg, casseri 4,5 m2. Costo (1998): 300 000 Lit.

Prontuario dell’ingegnere – Hoepli Renato Villa

Figure 2: Electronic version: a screen shot corresponding to the same spread shown in figure 1.

250 TUGboat, Volume 29 (2008), No. 2

Part Right icon Left icon

Environment A AChemistry B BEconomy C CBuilding D DElectronics E EPower electrical eng. F FEnergetics G GHydraulics I IComputers J JMachines K KProduction L LSurvey M MTelecommunications N NLand planning O OQuality Q QMiscellany P P

1

Figure 3: Right and left hand thumbnails.

the use of Italian hyphenation.2 The code was thefollowing:\expandafter

\ifx\csname language\endcsname\relax\else

\expandafter\ifx\csname l@italian\endcsname\relax

\typeout{La sillabazione per l’italianonon e’ definita.^^JUsero’ la sillabazione didefault e faro’ tanti errori!}%

\typeout{Verificare che la sillabazioneper l’italiano sia statacaricata^^Je che il suo nome sia associatoal comando \string\l@italian}%

2 Even today, although everything is much simpler, manyItalian users run LATEX to typeset Italian texts without con-figuring it for Italian!

Figure 4: The thumbnail shadow on the trimmedside of the second edition.

\language0\righthyphenmin 2\relax\lccode‘\’=‘\’

\else\def\italiano{\language \l@italian

\righthyphenmin 2\relax\lccode‘\’=‘\’}%

\italiano\fi

\fi

Well, today even these messages are built-in to thebabel package, and warning messages are much sim-pler to program. (The first message says: “Italianhyphenation is undefined. I’ll use the default hy-phenation and I’ll make a lot of errors!” The secondmessage says: “Verify that Italian hyphenation hasbeen loaded and that its name is associated to thecommand \l@italian”.)

6 ThumbnailsConcerning the thumbnail icons, we solved the prob-lem by designing their fonts, with white strokes overa black background, and with the background ex-tending well beyond the actual icon, so as to pro-trude into the right trimming area for the printedversion, or to protrude well to the left of the virtualPDF sheet border for the electronic version. Thissolution guarantees the visibility of the inked iconshadow on the trimmed pages of the printed ver-sion, even without the typical thumbnail semicircu-lar cut. Figure 3 shows the left and right icons, withthe extending background; initially they were pro-duced with METAFONT; but for the second editionthey were traced and rendered as scalable outlineType 1 fonts.

Figure 3 displays the icons on a wide black rect-angle, whose width goes beyond the trimmed page;this is why when pages are trimmed, the closed bookexhibits on the right trimmed side the thumbnailshadows, figure 4; probably this fact is not so im-portant while ‘navigating’ the handbook as the icon

TUGboat, Volume 29 (2008), No. 2 251

Figure 5: The published editions; on the left the first edition in size A5; on the right the second edition in size120 mm× 170 mm.

drawn on the flat side of the thumbnail—even whenrapidly flipping the handbook pages it’s very easy toidentify the icon one is looking for. It goes withoutsaying that the thumbnails of every part are progres-sively shifted down along the margin so that theyappear still when pages are rapidly flipped.

Even the electronic version, although it has itsicons on the left border and does not have pagesto be flipped through one’s fingers, benefits fromthe presence of such icons when the screen viewis rapidly scrolled up or down by operating on thescrolling arrows of the PDF reading program.

7 Internal hyperlinksThe various elements of the electronic version arecompletely hyperlinked with one another by meansof the hyperref package, so that surfing the docu-ment gets particularly simple when the colored an-chor texts are clicked upon. Even the table of con-tents entries and the index entries are hyperlinkedwith their sources. The sections that must refer toother sections are also hyperlinked. In this way theelectronic version is even more easily readable thanthe printed one. In the nineties this was a real nov-elty that has been appreciated by the readers.

8 The second edition modificationsThe second edition [3] underwent a few layout modi-fications compared to the first edition. The page sizewas reduced to the trimmed page size of 120mm by170mm, figure 5. The written and drawn parts ofeach record were interchanged as may be seen in fig-ure 6. The thumbnails were set on the left side, asin the electronic version, but in both versions theywere set a little closer to the text border. Togetherwith figure 6 it’s possible to examine a screen shotin figure 7. The thumbnail shadows remain visibleon the trimmed page side, figure 4.

9 The publishing house policyThe Hoepli Publishing Company is very well knownfor its (Italian) handbooks and, among engineers,for its Manuale del Colombo (Colombo’s Handbook).This work started in 1875 and was published inmany successive revisions so as to become almostencyclopedic, since it can no longer be used as origi-nally intended, as an easily workable handbook. Weall know that engineering sciences have evolved in anincredible way in the past century, so that the evo-lution of Colombo’s Handbook has been unavoid-able. For these reasons, in our Prontuario dell’Inge-gnere (The Engineer’s Quick Reference Handbook),

252 TUGboat, Volume 29 (2008), No. 2

Edil

izia

D

54 Strutture in calcestruzzo armato

PILASTRI

Materiali. Calcestruzzo di buona qualita con una resistenza a rottura dicirca 30 N/mm2 (v. Calcestruzzo, pag. 52). Armature di acciaio ad aderenza mi-gliorata con una resistenza a rottura di circa 440N/mm2 (v. Acciaio, pag. 50)

Carichi. I pilastri sono soggetti alle forze verticali dovute al peso sovrastan-te (carichi permanenti e accidentali). Se l’edificio e in zona sismica i pilastri, letravi e il blocco scale-ascensori devono resistere alle forze orizzontali causate dalterremoto (v. La struttura nel suo complesso, pag. 48). I carichi verticali sono paria circa 10 kN/m2 per ogni piano. Se un pilastro sostiene una soletta di 5 m×5 m= 25m2, ogni piano contribuisce con 250 kN al carico sul pilastro.

Sezione. Se N e il carico verticale e A la sezione trasversale, σ = N/A ela tensione di esercizio nel calcestruzzo per i carichi verticali. Si sceglie l’area Ain modo che la tensione di esercizio si mantenga inferiore ai valori prescritti. Siha che A = Ac + m As con Ac area del calcestruzzo, As area delle armature em (coefficiente di omogeneizzazione) uguale a 14. Inoltre As ' 0,01 Ac, con unminimo di 4 d 12. (In presenza di carichi orizzontali e necessario tener conto deimomenti flettenti che sollecitano i pilastri.)

Dimensioni in funzione del carico

N Ac a× a a× 25 As

kN cm2 cm×cm cm×cm cm2

250 321 18×18 15×25 4,4500 642 25×25 25×25 6,4750 963 31×31 39×25 9,6

1000 1285 36×36 51×25 12,91250 1606 40×40 64×25 16,11500 1927 44×44 77×25 19,31750 2249 47×47 90×25 22,52000 2570 51×51 103×25 25,7

Forma. Normalmente i pilastri sono rettangolari o quadrati (fig. A, B). Incasi particolari sono a L, a C, a T. Lo spessore dei pilastri che stanno lungo ilcontorno dell’edificio dipende dallo spessore della muratura. Di solito, pero, nonsi scende sotto i 20 cm. Le armature longitudinali vengono disposte negli angoli e,se occorre, lungo i lati della sezione ogni 30 cm circa. Il diametro delle armaturelongitudinali va da 12 mm a 20mm e solo eccezionalmente fino a 26 mm. Le staffeseguono il contorno della sezione e sono disposte a un intervallo di circa 15 cm. Ildiametro delle staffe va da 6 mm a 10mm. Il copriferro sulle staffe deve essere nonmeno di 2 cm (v. Acciaio, pag. 50).

Dettagli costruttivi. Riprese di armatura da piano a piano (fig. C). Pila-stri di sezione particolare (fig. D). Smussi negli spigoli: e opportuno prevederli di2,5×2,5 cm. Negli edifici in zona sismica le armature dei pilastri e quelle delle travidevono essere opportunamente collegate.

Casseri e getti. Modalita di disposizione dei casseri (fig. E). Modalita digetto: normale ma con particolare cura nella vibrazione. Tempo di maturazione:circa una settimana per tutti i pilastri di un piano.

Quantita e costi. Incidenza delle armature: da 120 a 140 kg di acciaioper m3 di calcestruzzo. Pilastro di 30 cm×40 cm, per piano di altezza 320 cm:calcestruzzo 0,38 m3, acciaio 50 kg, casseri 4,5 m2. Costo (2003): 150E.

Strutture in calcestruzzo armato 55

Renato Villa

Figure 6: Second edition printed version: a spread.

Edil

izia

D

35 Strutture in calcestruzzo armato

PILASTRI

Materiali. Calcestruzzo di buona qualita con una resistenza a rottura dicirca 30 N/mm2 (v. Calcestruzzo, pag. 34). Armature di acciaio ad aderenza mi-gliorata con una resistenza a rottura di circa 440 N/mm2 (v. Acciaio, pag. 33)

Carichi. I pilastri sono soggetti alle forze verticali dovute al peso sovrastan-te (carichi permanenti e accidentali). Se l’edificio e in zona sismica i pilastri, letravi e il blocco scale-ascensori devono resistere alle forze orizzontali causate dalterremoto (v. La struttura nel suo complesso, pag. 32). I carichi verticali sono paria circa 10 kN/m2 per ogni piano. Se un pilastro sostiene una soletta di 5m×5 m= 25 m2, ogni piano contribuisce con 250 kN al carico sul pilastro.

Sezione. Se N e il carico verticale e A la sezione trasversale, σ = N/A ela tensione di esercizio nel calcestruzzo per i carichi verticali. Si sceglie l’area Ain modo che la tensione di esercizio si mantenga inferiore ai valori prescritti. Siha che A = Ac + m As con Ac area del calcestruzzo, As area delle armature em (coefficiente di omogeneizzazione) uguale a 14. Inoltre As ' 0,01 Ac, con unminimo di 4 d 12. (In presenza di carichi orizzontali e necessario tener conto deimomenti flettenti che sollecitano i pilastri.)

Dimensioni in funzione del carico

N Ac a× a a× 25 As

kN cm2 cm×cm cm×cm cm2

250 321 18×18 15×25 4,4500 642 25×25 25×25 6,4750 963 31×31 39×25 9,6

1000 1285 36×36 51×25 12,91250 1606 40×40 64×25 16,11500 1927 44×44 77×25 19,31750 2249 47×47 90×25 22,52000 2570 51×51 103×25 25,7

Forma. Normalmente i pilastri sono rettangolari o quadrati (fig.A, B). Incasi particolari sono a L, a C, a T. Lo spessore dei pilastri che stanno lungo ilcontorno dell’edificio dipende dallo spessore della muratura. Di solito, pero, nonsi scende sotto i 20 cm. Le armature longitudinali vengono disposte negli angoli e,se occorre, lungo i lati della sezione ogni 30 cm circa. Il diametro delle armaturelongitudinali va da 12mm a 20mm e solo eccezionalmente fino a 26 mm. Le staffeseguono il contorno della sezione e sono disposte a un intervallo di circa 15 cm. Ildiametro delle staffe va da 6mm a 10mm. Il copriferro sulle staffe deve essere nonmeno di 2 cm (v.Acciaio, pag. 33).

Dettagli costruttivi. Riprese di armatura da piano a piano (fig.C). Pila-stri di sezione particolare (fig. D). Smussi negli spigoli: e opportuno prevederli di2,5×2,5 cm. Negli edifici in zona sismica le armature dei pilastri e quelle delle travidevono essere opportunamente collegate.

Casseri e getti. Modalita di disposizione dei casseri (fig. E). Modalita digetto: normale ma con particolare cura nella vibrazione. Tempo di maturazione:circa una settimana per tutti i pilastri di un piano.

Quantita e costi. Incidenza delle armature: da 120 a 140 kg di acciaioper m3 di calcestruzzo. Pilastro di 30 cm×40 cm, per piano di altezza 320 cm:calcestruzzo 0,38m3, acciaio 50 kg, casseri 4,5 m2. Costo (2003): 150E.

Renato Villa

Figure 7: Second edition electronic version: a screen shot of the same spread shown in figure 6.

TUGboat, Volume 29 (2008), No. 2 253

only the essential elements of the various engineer-ing disciplines were included, and those condensed.The purpose is to give essential information to thosewho are not experts in a particular discipline, butwant to understand the basic principles. This neces-sity arises also from the always increasing coopera-tion between engineers and architects, each expertin their respective fields. Therefore the Quick Ref-erence meets the need of understanding one anotherand easing communication among technical staff.

The graphic solution by records (a spread in theprinted version) came naturally in order to show inthe most simple and schematic way the various sub-jects. The work had to have a synthetic and essentiallook. The importance of the technical drawings re-quired a whole page for each subject, so the otherpage was dedicated to the text. This unusual ar-rangement was of great importance for the LATEXstructure and for the very management of the edit-ing work.

AG had significant experience as the editor ofColombo’s handbook with about one hundred andfifty collaborators, so he had no difficulty findingthe forty plus collaborators for the Quick Reference.The difficulty was in the coordination and the choiceof what to write in this Quick Reference and in whichdetailed form to write it in the records. A generalidea of the text length was given to the authors, butit was the editor’s task to cut down lengthy contri-butions or to request some additional material forexcessively short records.

To coordinate a few dozen authors is an inter-esting task, because authors are very different fromone another from both the scientific and a humanpoint of view. They range from the very precise andpedantic personality to the excessively ingenious andchaotic one. All of them, though, are very inter-ested to see their experience take form and becomea real printed object. Moreover, they were passion-ate about extracting a synthesis of their knowledgefor the book. Many of them are true professionals,but with little experience as technical writers. Forthese reasons the coordination task revealed itself asheavier that foreseen, but at the end the editor andthe authors were very satisfied.

At the moment (2007) at the publishing housethey are working on the third edition, whose pub-lication should be around May 2008. At the be-ginning of 2007 the publishing house opened a newInternet site, http://www.manualihoepli.it/, in-tended to give information on the various publishedhandbooks, and to publish integrations and updatesthat users may freely download. This site containsseveral pages from the Quick Reference, since they

are evidently assumed to be both interesting andgood general advertising on behalf of the HoepliPublishing Company.

This third edition will contain few modifica-tions, compared to the second one, the most relevantof which is an increase in size, so that it is possibleto increase also the font size and the legibility.

10 ConclusionThe Quick Reference has been a wonderful occasionfor both AG and CB to learn how to use to its bestadvantage such a powerful instrument as LATEX. Thebook received a well deserved success so that, as saidbefore, a third edition is under way; it contains notonly upgraded information, but also the correctionof some remaining typos.

Today, to create a similar work, from the pointof view of the typesetter, would be much simpler,when one considers that most operations that werenecessary to ‘invent’ when the first edition was pub-lished, are now mostly available with the countlesspackages, produced in the past 10 years, that haveextended LATEX’s functionality.

Today the available packages allow us to cre-ate the necessary macros in a more orderly way,but most important, in a well-documented manner[5]; they allow building up typesetting structuresin a simpler way by means of high level user com-mands made available by the extension packages:the graphic formats can be chosen more easily bymeans of the geometry package [8]; fonts can be cho-sen and configured with one statement, for exampleusing the extended Times fonts [7], or the extendedPalatino ones [6]; the style of titles and running ti-tles can be defined with high level user commands[4]; the same is true for headers and footers [9]; eventhe handling of figure sets does not require the man-ual graphic editing as previously described [1].

Nevertheless all these packages, although ex-tremely useful, if used by amateurs allow the cre-ation of graphic designs that are not the best onecan achieve.

Luckily, in this work the interaction betweenthe LATEX programmer and those giving the designspecification had a particular positive synergy. Thistype of collaboration allowed setting reasonable lim-its to the graphic novelty involved, thanks to boththe experience of AG and the interaction with CBwho could indicate what was and was not feasiblewith LATEX and the typesetting interpreter TEX.

Thanks to this cooperation between the editors,specifying unrealizable requirements for the graphicdesign and the page layout was avoided. In truth,even though LATEX and TEX are extremely powerful,

254 TUGboat, Volume 29 (2008), No. 2

they are computer programs that operate in batchmode, not interactively. This is their strength andtheir weakness, since they are not (yet) at the level ofthe modern interactive pagination programs mostlyused by publishing companies, but are far superiorin typesetting paragraphs and mathematical expres-sions.

References[1] Steve Douglas Cochran. The Subfig package,

2005. Normally distributed with the TEXsystem, documentation in file doc/latex/subfigure/subfig.pdf.

[2] Giuseppe Colombo. Manuale dell’ingegnere.Hoepli Editore, Milano, 84 edition, 2003.

[3] Andrea Guadagni, editor. Prontuariodell’ingegnere. Hoepli Editore, Milano, 2edition, 2003.

[4] Ulf A. Lindgren. FncyChap, 2005.Normally distributed with the TEX system,documentation in file doc/latex/fncychap/fncychap.pdf.

[5] Frank Mittelbach. The doc and shortvrbpackages, 2006. Normally distributed with theTEX system, documentation in file doc/latex/base/doc.pdf; see also doc/latex/base/docstrip.pdf.

[6] Young Ryu. The PX fonts, 2000.Normally distributed with the TEX system,documentation in file doc/fonts/pxfonts/pxfontsdocA4.pdf.

[7] Young Ryu. The TX fonts, 2000.Normally distributed with the TEX system,documentation in file doc/fonts/txfonts/txfontsdocA4.pdf.

[8] Hideo Umeki. The geometry package, 2002.Normally distributed with the TEX system,documentation in file doc/latex/geometry/manual.pdf.

[9] Piet van Oostrum. Page layout in LATEX, 2004.Normally distributed with the TEX system,documentation in file doc/latex/fancyhdr/fancyhdr.pdf.

� Claudio Beccariclaudio dot beccari at gmail dot com

� Andrea Guadagniandrea dot guadagni at tin dot it