24 OAH Magazine of History • April...

Transcript of 24 OAH Magazine of History • April...

24 OAH Magazine of History • April 2011

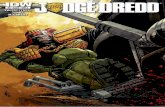

Figure 1. In June 1857, in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court proslavery ruling in Dred Scott v. Sanford, Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly sought out Dred Scott in St. Louis, and found the Scott family — Dred and Harriet below, and their daughters, Eliza, left, and Lizzie, right. The story behind the lawsuits — both Dred and Harriet sued for their freedom — is not comprehensible unless the family as a whole is taken into account. (Courtesy of Library of Congress)

at :: on Novem

ber 20, 2012http://m

aghis.oxfordjournals.org/D

ownloaded from

OAH Magazine of History , Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 24– 28 doi: 10.1093/oahmag/oar010© The Author 2011. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Organization of American Historians.All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: [email protected]

Dred Scott — the name echoes through American history. Nearly every textbook tells the familiar story: the enslaved Dred Scott, having been taken by his master into free territory, sues in

1846 for his freedom under the prevailing law of slave transit, wins in the lower court, but eventually loses in a 1857 U.S. Supreme Court rul-ing. Led by Chief Justice Roger Taney, the court overturns the Missouri Compromise and Northwest Ordinance and denies any legal rights to African Americans, slave or free ( 1 ). Many of us know Dred Scott v. Sanford as one of the key milestones on the road to the American Civil War. But few are aware that the lawsuit that rocked the nation involved an entire family: Mr. Dred Scott, Mrs. Harriet Scott, and their daugh-ters, Eliza and Lizzie ( Figure 1 ).

Both Dred and Harriet fi led lawsuits in Missouri. The timing of their lawsuits, which they technically might have fi led years earlier, was tied up with fears that Eliza and Lizzie might be sold away from them. Although the Scotts had both been born slaves in Virginia, they had reason to believe they were legally entitled to freedom since they had both been brought by their respective masters to a settlement at the headwaters of the Mississippi Valley in what is now Minnesota. The Northwest Ordinance banned slavery in the entire region north of the Ohio River, including the Minnesota location where Dred and Harriet had lived ( 2 ). By the 1830s, when Dred and Harriet met and married, it was well-established that slaves would be deemed free in court if they had lived in the North where slavery was banned. But in the Scotts ’ case, the U.S. Supreme Court changed the rules. Congress could play no further role in eliminating slavery from American terri-tory unless the states took up the overwhelming challenge of changing the U.S. Constitution. And so, the predicament of one family became tied up in the fate of the nation as a whole.

Slavery Beyond the South It is indeed ironic that the lawsuit that brought the question of slavery to the forefront and impelled the nation to civil war was brought by an American family who had lived in what is now Minnesota, and then moved beyond the periphery of the settled American territory in the far North. Dred served John Emerson, a U.S. army doctor working at Fort Snelling attending the soldiers based at this remote outpost of American military authority ( Figure 2 ). Harriet served the United States Indian Agent, Lawrence Taliaferro, who was the U.S. government’s represen-tative in dealing with the Dakota nation.

The place that they met was perhaps the most remote region of American territorial settlement. Now located just outside a suburb of Minneapolis, the fort was then so far from the rest of the settled world that the surroundings had not yet been mapped by mapmakers. The forts were solitary outposts. There was no town anywhere near Fort Snelling, only the fort itself and less than half a dozen outlying houses. The next closest settlement, Fort Crawford, was fully two or three days

distance by boat. The entire settlement community was comprised of the soldiers and offi cers and a few offi cers ’ wives. Other slaves, like Dred and Harriet, had been brought to the frontier to help with the needs of survival in a wilderness with a harsh winter. Almost every army offi cer had an African American servant to prepare meals, groom horses, and keep quarters clean and warmed by fi re. Because there was no surrounding population of settlement people from which to hire servants, most offi cers actually acquired slaves from the St. Louis slave market before moving north to the fort where they would be stationed, sometimes for years ( 3 ). The harsh winters meant that when the Mississippi River froze there was virtually no way to reach the fort, and no way to leave. As a result, any slaves brought against their will had no hope of escaping.

Although the area was remote, it was not desolate of population. The Dakota people inhabited the region, but since they were nomadic and lived in tribes, there were no established Dakota towns. The Dakota tribes moved from season to season to different traditional camping grounds where they would set up their tents to fi sh, gather rice and cranberries, plant patches of corn, and pursue wild game. They sold fur-bearing animals — beaver, fox, bear, and muskrat — to American Fur Company traders at trading posts in exchange for food and other utensils. In fact, the land throughout the region belonged to the Dakota people until it was later sold to the U.S. government by treaty. Meanwhile, the Ojibwa people, based further east, were increasingly moving west to hunt on Dakota lands. The Ojibwa had been pushed off their own lands by increasing settlement and by having overhunted the fur-bearing ani-mals. The tension between the two Native American nations was one of the critical issues in the community, and it was the task of Harriet’s master, Lawrence Taliaferro, to attempt to keep the peace. Because the Indian agent’s job was to meet and communicate frequently and regularly with the Indians, he lived outside the fort’s confi nes in an unprotected wooden house a quarter mile from the fort’s walls. There, Harriet grew up in a household of three members of her master’s family and a few servants like herself. The household received daily visitors from Indian tribes even though the language difference meant that the household had to rely on interpreters to converse with the Indians ( 4 ).

At the Indian agency house, young Harriet grew from a teenager to a young woman, and in time, Taliaferro gave her in marriage to Dred Scott, a man twenty years her senior. Taliaferro performed a marriage ceremony for them, much as he had married other persons in the com-munity who came to him to perform their weddings. Since Harriet’s master was leaving for the winter, the agency house was closed up and Harriet went to live with her husband at his room inside the fort’s walls. The Scotts ’ living circumstances were very different from what we customarily imagine of slaves living in the South. They were not chained or shackled. There is no evidence they were ever beaten. They

Lea VanderVelde

The Dred Scott Case as an American Family Saga

at :: on Novem

ber 20, 2012http://m

aghis.oxfordjournals.org/D

ownloaded from

26 OAH Magazine of History • April 2011

could wander around the area at will as long as they got their work done, and there was no overseer watching their every move.

After Harriet moved in with Dred, Dr. Emerson, the master who had brought Dred north, went off in search of a wife of his own. It is not exactly clear what Harriet and Dred’s legal status was as they stayed on in the Minnesota region. Other offi cers offered Harriet and Dred work at the fort for the winter. Harriet’s former master had clearly relinquished ownership over her, but there was no pos-sibility for her to establish her freedom more formally because there was no court within two hundred wilderness miles of where she lived. The only way she could do so was to go to court and sue for her freedom.

Family Matters That spring, two more circumstances changed the Scotts ’ lives. First, Harriet became pregnant with their fi rst child, and second, Dr. Emerson, Dred’s old master, found a wife in the South and sent for the Scotts to join him. Whether Dr. Emerson was asking or telling Dred to join him, Dred and Harriet still needed a means to support themselves with jobs, and the offi cers at the fort would probably have been reluctant to offer them work contrary to Dr. Emerson’s wishes. That spring, their employment at the fort ended, and when the river

thawed, the Scotts left the fort and travelled south. They went at least as far as St. Louis, which was the terminus of all steamboats traveling north, south, or east.

How and when the Scotts met Dr. Emerson again, and what they discussed about the terms of Dred’s or Harriet’s continued service, is unknown. What is known, and even more remarkable, is that Dr. Emerson now wanted to return north to free territory again and Dred and the very pregnant Harriet did accompany him and his new bride. We know that Eliza, the Scott’s fi rst child, was born on the steamboat Gypsey , and that at the time of her birth, the boat was north of the famous parallel dividing the free North from the slave South ( 5 ). Eliza was born in free territory, of parents who could not be held as slaves in free territory.

There is some indication that the Scotts ’ might have thought about establishing their freedom during the summer they visited St. Louis, but there is no clear evidence that they started the process ( 6 ). With another mouth to feed, they needed work which Dr. Emerson appar-ently offered them. Back at Fort Snelling, Dr. Emerson even put his own personal reputation on the line to arrange for them to have their own stove in their quarters for the winter. In these circumstances, it seems that the Scotts made the choices necessary for survival by remaining in Dr. Emerson’s service ( 7 ).

Figure 2. In the 1830s, Harriet and Dred Scott lived, were married, and worked at Fort Snelling, the major U.S. Army outpost in the upper Mississippi region. With increasing white immigration, and the establishment of nearby Minneapolis, the military’s need for the fort declined and it was sold to a land developer in the 1850s. In the early 1900s, when this photograph was taken, the round tower was one of the few original structures still standing. Restoration of the fort was under-taken in 1960 and completed in 1979. (Courtesy of Library of Congress)

at :: on Novem

ber 20, 2012http://m

aghis.oxfordjournals.org/D

ownloaded from

OAH Magazine of History • April 2011 27

Over the next several years, similar options would present themselves, and each time, the Scotts chose those that preserved their family stability and survival, even if doing so put off the ulti-mate decision to establish their freedom legally. After the Scotts returned north, and in fact for the entire duration of their residence there, no court existed within two hundred miles. Virtually any route back from the wilderness outpost to more settled regions took them through the St. Louis terminus in the slave state of Missouri, and for most purposes St. Louis was the major court through which other former slaves living in the North had achieved their freedom.

What prompted the Scotts to fi nally abandon the Minnesota region in 1840 was a twofold change in national policy. First, the Seminole War fl ared up again, and a military decision was made to deploy the troops from the Northwest forts, including Dr. Emerson, to Florida. With this redeployment of troops, there would have been almost no one in the fort to employ Harriet and Dred. Second, the United States decided to put a stop to squatters building cabins around Fort Snelling. This led to a military order to burn down all the squatter cabins that had been built outside the fort. The Scotts could not have sought shelter for the winter in a cabin of their own because all of the non-military cabins were being burned to the ground. The only option for their survival was to board the steamboat heading south with Dr. Emerson and his wife ( 8 ).

Suing for Freedom Once Harriet and Dred returned to St. Louis in 1840, six years would go by before the Scotts fi led suit for their freedom. Why did they wait so long? One reason was that fi ling suit for freedom was often an ardu-ous ordeal; it was not something that a slave did lightly. Petitioners seeking their freedom could spend months or years waiting in jail. At the same time, the courts were unwilling to free African Americans on their own recognizance while they were suing for freedom. Therefore, some were returned to their masters, who were often none too happy about being sued by their slaves. Some were placed in jail to wait for the disposition, running up a fee for the jailer, and some were hired out to work for the highest bidder. In this sense, suing for freedom some-times made their living circumstances worse than before they had asserted their claims for freedom. Between 1840 and 1846, when the Scotts together fi led suit for freedom, the family managed to stay together. The Scotts were hired out to an interesting variety of masters

both in the city of St. Louis and at Jefferson Barracks. Harriet had more children, two sons who died in infancy, and another daughter born at Jefferson Barracks, whom the Scotts named Lizzie. After the outbreak of the Mexican War in 1846, Dred went off with the Army of Observation to Louisiana and later Corpus Christi, Texas, while Harriet and their daughters waited for him in St. Louis ( 9 ). Harriet did not sue without Dred, but once he returned from Texas, within days each of them had fi led suit separately seek-ing freedom for themselves and their family.

Why did the family sue then? By this time, the relatively benevo-lent Dr. Emerson, who had left the Scotts alone, had died and now his widow was seeking to control them. Mrs. Emerson refused Dred’s offer to buy his own free-dom by working it off. More poi-gnantly, Dred, who by now was considered aged and suffered from tuberculosis, was not worth very much. But his younger wife, Harriet and eight-year-old Eliza and little Lizzie were considered valu-able human assets. Mrs. Emerson’s claim to them was tenuous, but then Harriet had not yet estab-lished her freedom papers, and the girls ’ status depended upon the status of their mother; if Harriet was free, so too were her daughters Eliza and Lizzie. If Harriet was deemed enslaved, however, then Eliza and Lizzie would follow their mother’s designation. Of particu-lar risk to the family was the possi-bility that eight-year-old Eliza had reached the age when masters sold

children separately from the family. In these circumstances, the time had come to fi le suit to establish the family’s freedom, even if it meant being imprisoned.

And so they did. Harriet and Dred each fi led separate suits for freedom on April 6, 1846. The Missouri law was clear and they should have won easily. No suits were fi led for the girls, because once their mother was adjudged free, it would be easy to establish their rights. And if the parents needed to bear the brunt of jail, were returned to their master, or hired out, then the girls were spared these indignities for the duration of the case. What the Scotts could not have anticipated were the fi res and epidemics that would delay their lawsuit. Neither could they have anticipated that some careless lawyers would fail to make their case. But, more importantly, they could not have foreseen that the Missouri Supreme Court fi rst, and the U.S. Supreme Court later, would change the law in their specifi c cases when they requested freedom.

Figure 3. U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney (1777 – 1864) wrote the 1857 decision denying the members of the Scott family their freedom. According to Taney, Congress had no right to restrict slavery anywhere. Furthermore, no black person, either slave or free, could be considered a citizen. Taney’s decision was a crucial factor in polarizing American sectional politics in the 1850s. (Cour-tesy of Library of Congress)

at :: on Novem

ber 20, 2012http://m

aghis.oxfordjournals.org/D

ownloaded from

28 OAH Magazine of History • April 2011

The details of the Scotts’ ordeal are an American saga. In 1852, after thirty years of freeing slaves who had resided on free soil, the Missouri Supreme Court reversed its previous ruling and declared that it would no longer recognize residence in free territory as grounds for freedom. By then, the Scotts had gone through two jury trials, and two appeals. At the time that the Missouri Supreme Court reversed its course, the Scotts believed themselves to have been declared free for two whole years ( 10 ). Faced with this serious setback, they fi led suit in federal court and sent their daughters into hiding. The federal case took another fi ve years, and gained national prominence when it was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court as the case which would test a number of key matters in the process of the abolition of slavery.

Many historians believe that the election of President Buchanan, just before the U.S. Supreme Court announced its ruling, infl uenced the Court’s result. In 1857, the Supreme Court split seven to two, writ-ing one of the longest opinions it had ever rendered, and decided against the Scotts. Every justice felt compelled to write something, but threading through the majority opinions was the ruling that the Scotts could not sue in federal court for their freedom because they were not citi-zens of the United States or citizens of any nation. This holding was expressly based upon their race. Chief Justice Taney wrote that African Americans had no rights that white men were deemed to respect and could not be or become citizens of the United States ( Figure 3 ). The Court

also foreclosed the possibility that Congress could pass any laws helping slaves like the Scotts. The Court reached this result by declaring that two acts of Congress were unconstitutional: the Northwest Ordinance and the Missouri Compromise, which had declared certain federal territorial regions to be free. The decision ran through the nation like a bolt of light-ning. Southern states applauded while Northern states recoiled in horror.

Who owned the Scotts after all? By now, Dr. Emerson’s widow had married Dr. Calvin C. Chaffee, a gentleman from Massachusetts who served in the House of Representatives with the Free Soil Party. To his profound embarrassment, this Northern political fi gure became aware that as husband to his wife and thereby owner of her property, he held enslaved the most politically controversial couple in the United States. Chaffee quickly transferred ownership to someone in Missouri who could free the Scotts. And so, the Scotts, all four of them, Dred, Harriet, Eliza, and Lizzie were registered in St. Louis Court as free persons. They were fi nally freed not because they won their case, but because their ownership had embarrassed a Northern politician. Finally, as free persons, no one had the power to separate members of the family from each other or to sell anyone away.

The Scotts ’ basic desire was to be able to stay together as a family without interference by masters. The Scotts were now free persons, but as African Americans they were still denied the opportunity to partici-pate in the American social compact. The Supreme Court had gone even further than necessary in their case, holding that even free African Americans were not citizens of the United States, could not sue for violations of their rights in the United States courts, and did not have any rights which white persons were required to respect ( 11 ). Although the Scott family lived a distinctively American experience, they were excluded from the American family.

It would take amendments to the Constitution to change that. But fi rst, there would be armed confl ict between the North and the South.

Endnotes 1 . Dred Scott v. Sanford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857). 2 . Northwest Territorial Ordinance of 1787, article 6. “There shall be neither

slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory . . . .” 3 . John H. Bliss, Reminiscences of Fort Snelling (St Paul: Minnesota Historical

Society Press, 1894). 4 . The circumstances of Harriet and Dred’s life in Minnesota are detailed

extensively in Lea VanderVelde, Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery’s Frontier (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

5 . See Lea VanderVelde, Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery’s Frontier , 135 – 36. The United States Supreme Court even documents the boat’s position at the time of Eliza’s birth as north of the parallel of the Missouri Compromise.

6 . See VanderVelde, Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery’s Frontier , 132. 7 . See VanderVelde, Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery’s Frontier , 169 – 70 8 . See VanderVelde, Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery’s Frontier , 168 – 75. 9 . See VanderVelde, Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery’s Frontier , 205 – 32. 10 . Scott v. Emerson , 15 Mo. 576 (1852). 11 . Dred Scott v. Sanford , 60 U.S. 393 (1857).

Lea VanderVelde is the Josephine R. Witte Professor of Law at the University of Iowa College of Law and is currently a Guggenheim fellow in Constitutional Studies. She is the author of Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery’s Frontier (Oxford University Press, 2009). Her current book projects include Slaves in the Land of Lincoln and Redemption Songs: How Slaves Sued for Freedom in St. Louis Courts. VanderVelde played a role in the discovery of almost three hundred previously unknown freedom suits brought by slaves in the St. Louis courts, which are now available online at < http :// www . stlcourtrecords . wustl . edu / about - freedom - suits - series . php >.

Figure 4. Dred and Harriet were separated in death, buried in separate cemeteries. Due to his fame, Dred was buried by the person who formally freed him in the otherwise all-white Calvary Cemetery in the city of St. Louis. Three plots were purchased and Dred laid to rest in the center plot, seen here, so that no white person would need to be buried next to an African American man. Harriet was buried in the all-black Greenwood Cemetery in St. Louis County. Her unmarked gravesite, lost for years, has recently been discovered and rededicated. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons) at :: on N

ovember 20, 2012

http://maghis.oxfordjournals.org/

Dow

nloaded from