23-Autumn-2005

-

Upload

annebricklayer -

Category

Documents

-

view

53 -

download

2

Transcript of 23-Autumn-2005

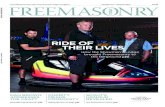

AUTUMN 2005 B U L L E T I N

B R I C K

CITYLIVINGA picture galleryof modern, brick,urban residentialschemes

CHIC ANDSLEEKBrick House isCaruso St John’sultramodernmasterpiece

PREFABDOUBTSJohn Outrammakes his caseagainst off-siteconstruction

IT’S OH SOQUIET …… but this newtown library ismaking some noisein Hampshire

THE HARDWORDAll you need toknow about brickdurability andfrost resistance

DOUBLEHONOURS

Why Allies and Morrison’s pair ofCambridge University buildingstriumphed at the Brick Awards

Architect Allies and Morrison hasscooped the BDA’s top Building ofthe Year award with itsimpressively cool buildings forFitzwilliam College, Cambridge(see pages 8-10). The award wasmade at the culmination of theBDA Brick Awards 2005 galaevening, held on the 2 Novemberat the Grosvenor House Hotel inLondon.

Unusually for a Brick Awardswinner, Allies and Morrison’sentry comprised two distinctbuildings – a rational, three-storey, mauve brick gatehouseand a contrasting creamy buff brick auditorium buildingwith abstract elevationalcompositions. Both extend SirDenys Lasdun’s original 1958masterplan for Fitzwilliam andmake a significant contribution tothe role of brick in modernarchitecture. The judges wereimpressed by the two buildings,which enhance the academicenvironment and complement analready distinguished line-up ofbuildings on the campus. Theproject was also awarded theBest Public Building Award.

Best Private Housing

development went to The Matrixin Glasgow by Davis DuncanArchitects, a contemporarydevelopment of 73 apartments,café–bar and office space thathas created a powerful urban

landmark. BPTW Partnership’sPepys Estate in London, anelegant project characterised byits refined detailing, took BestPublic Housing Development. AndFeilden Clegg Bradley’s central

headquarters for the NationalTrust in Swindon, a building witha strong industrial geometry thatwas inspired by local railwaysheds, took the Best CommercialBuilding award.

A double first for Cambridge

2 ● BRICK BULLETIN

Get your own copy of Brick BulletinFed up of reading somebody else’s copy of Brick Bulletin? You can have your own regular copy of Brick Bulletin sent direct to you. Simply callthe Brick Development Association on 01344-885651. Alternatively, this and past Brick Bulletins can be downloaded from www.brick.org.uk

Allies and Morrison’s Fitzwilliam College buildings scoop prizes at 2005 Brick Awards

The winners in full are:BDA Building of the Year 2005and Best Public Building Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, by Allies and Morrison

Best private housing developmentThe Matrix, Glasgow, by Davis DuncanArchitects

Best public housing developmentPepys Estate, London, by BPTW Partnership

Best commercial buildingNational Trust New Central Offices, by

Feilden Clegg Bradley Architects

Volume housebuilding award Countryside Properties

Best refurbishment projectOak House, East Hampshire. Stedman BlowerArchitects

Best landscape projectChurch Street enhancement project,Nuneaton, by Nuneaton & Bedworth council

Best export awardJersey Airport Fire Training Ground, by

Dr John Knapton and Quintin Murphin of the States of Jersey Engineering Department

Innovative use of brick and clay productsLye Corner House, Thaxted, Essex, by SnellDavid Architects

In the opinion of the Judges, the followingprojects merited a special award:

Brick House, London, by Caruso St. JohnArchitects (see pages 6-7)

Bank Top Project, Blackburn, by UrbanRenewals (Blackburn & Darwen council)

The auditorium at Fitzwilliam College was one of the reasons why it won top prize at this year’s Brick Awards

BRICKBULLETIN ● 3

This issue of Brick

Bulletin coincides with

the Brick Awards. It

showcases a number of

buildings entered in the

awards that demonstrate the wide

variety of buildings that the judges are

presented with each year.

Whereas some architects are prepared

to explore the rich diversity offered by

the use of brick, others seem content to

indulge in the use of materials that are

not so challenging or rewarding.

Protagonists of the off-site movement

have sought to polarise views,

presenting prefabrication as a Holy Grail

and in-situ construction as archaic

practice. This distinction is as false as it

is irrelevant because in order to solve

the problems of the supply chain we

need a fully functioning industry.

It is just as important to try to foster

the growth of off-site, as it is to review

on-site practices and develop

rationalised masonry construction. The

whole industry needs investment of

time and thought. However, the ultimate

question is not how we build but what

we build.

Unless we make spaces and places

that enhance people’s lives we are all

wasting our time. Some materials have

helped to enhance people’s lives for

many generations and they have the

potential to continue to do so despite

the changing context of construction.

I hope this issue makes that point.

Michael Driver, director,

Brick Development Association

B U L L E T I N

B R I C K

The BDA is to launch softwarethat has been designed to makedesigning with brick faster andeasier. In place of manualcalculation, the program does itfor you by converting externalwall face dimensions of thebuilding into brick dimensions.The software relies on DXF filesimported from a CAD package.

Once the brick and mortar sizehave been entered and startingpoints defined, the programmewill start the calculation. Ifneeded the solution can berefined by flipping back to theCAD package. It is compatiblewith Windows 2000 and XP butnot yet with AppleMac. Watchthis space for further details.

Brick dimensioning software

Construction history congress

editor George Demetri co-ordinating editor Joannah Connolly designer Sam Jenkins reproduction London Pre-press printed by St Ives plc ISSN 0307-9325

An impressive case for thesustainable potential of brick hasbeen provided by the recentlycompleted £1.95m HQ buildingfor Neal’s Yard Remedies inGillingham, Dorset. ArchitectFeilden Clegg Bradley’s strongenvironmental agenda led it tospecify unfired clay bricks as ameans of reducing the embodiedenergy of the structure and helpgive the project the potential ofdeveloping into a zero carbonmanufacturing facility.

Project architect Alex Morrisexplains: “Because the building isof predominantly lightweightconstruction, we wanted to

increase its thermal mass to helpregulate summer temperatures.The embodied energy of theunfired bricks is lower than mosthigh mass materials.”

Dried in waste heat from thekilns, the “green” bricks werefound to have an averagecompressive strength of 4.9 N/mm2, allowing their useinternally to support their self-weight. They were finishedwith a breathable clay plasterand are expected to contributeto a healthier workplace byabsorbing and releasing moistureinto the environment.For details, call 01344-885651

The Second International Congress onConstruction History will be held atQueen’s College, Cambridge on 29March–2 April 2006. Aimed at buildingindustry professionals working inconservation in the UK and beyond, thecongress aims to highlight the state ofplay in the subject and showcase thelatest in conservation thinking.

Set to be the largest event of its kind ever held, about 250 speakersfrom around the world are lined up to deliver what promises to be ahighly informative and fascinating occasion. Indeed, so popular is theevent proving, that the organisers have received more than 400abstracts for consideration. The call for papers has now closed.Further information can be found at www.chs-cambridge.co.uk.■ Keen on construction history? Then join the Construction HistorySociety. For an annual fee of £18, you will receive the CHS newsletterand 24-page magazine, which includes details of all CHS events. Opento those from professional and academic backgrounds, membershipinformation can be obtained from [email protected].

Green bricks for ahealthy workplace

BRICKS AND THE CITY Not all brick-built city homes are

Georgian townhouses or Victorianterraces, as these contemporary

entries to the Brick Awards show

IN PICTURES

B

A

BRICK BULLETIN ● 5

The Matrix, Glasgow

The result of a

Glasgow council design

competition, the Matrix is

an £8.5m mixed-use

development of apartments,

offices and café–bar

completed in November

2004. The three major

architectural elements

contain 73 flats in blocks of

up to seven storeys high.

Davis Duncan was the

architect.

London Road

housing, Glasgow

This ship-like Glasgow

housing development

uses a combination of

blue and buff bricks for

variance in colour and

texture. The building’s

form is characterised by

the radiused end and the

striking roof canopy.

Page & Park was the

architect.

House, Garway

Road, west London

Russell Jones’ dramatic

design for this

contemporary house

in west London has

loadbearing brickwork

that features a hard,

ivory brick specially

developed by the

brickmaker. The use

of hydraulic lime

mortar has obviated

the need for movement

joints.

Park Rock,

Nottingham

A fresh take on the

19th-century suburban

villa, this project

comprises mostly

duplex executive

apartments in six

villas linked by glass

staircases. Letts

Wheeler Architecture

and Design has used

brickwork on the lower

floors of the highly

articulated elevations.

Westfield Student

Village, east London

Feilden Clegg Bradley’s

new student village for

Queen Mary College

in east London is one

of the largest of its

kind in Britain, providing

995 bed spaces in flats

and maisonettes. Two

types of brick were used

to contrast with the

rectilinear grid.

E

D

C

B

AC

ED

MONASTIC MINIMALISMDoing exactly what itsays on the tin, theCaruso St John-designedBrick House in westLondon is a rare exampleof an ultramodern, all-brick building thatdefies expectations ofspace and style. ByGeorge Demetri

very now and then, a project comes alongwhere brickwork not only features externally,but is also the major constituent of theinterior. One recent manifestation of this rare

breed is an ingenious and spatially complex housecompleted in April 2005 by Caruso St John Architects.

Brick House is unusual in two respects. Firstly, allinterior walls and floors are in fairfaced brickwork. Andsecondly, built on a difficult, highly irregular shaped sitesurrounded by other buildings, the house’s minimalexternal form is seen only from glimpses, either fromthe pavement or from neighbouring houses. What hasresulted therefore, is a house that is all interior andlittle exterior – a bit like the Tardis.

The almost complete lack of street frontage and thecomplicated site made it difficult to adopt a westLondon residential typology. Project architect RodHeyes says: “The interior plan is completely separatefrom the typologies of the London townhouse or theinner city loft, yet it still retains a strong sense ofdwelling in the heart of the city.” Indeed, if typologiesare what you are after, then city churches more readilyspring to mind, with their transcendental character intotal contrast to the hustle of the city.

Arranged over two floors, Brick House is entered atthe upper level through the facade of the adjacentVictorian terrace. The site’s outline has resulted incomplex-shaped living accommodation that is knittedtogether by an all-encompassing use of brick to providea consolidated surface. Comprising three bedrooms plusstudy and all associated living areas, the house’sspacious interior has some fairly irregular spaces thatlook out on to a total of three courtyards.

Brick was chosen not only for its contextualappropriateness, but also for its visual, thermal andacoustic mass. Heyes says: “The use of one materialbinds the whole building into an enveloping body,emphasising a skin-like character over any tectonicexpression. The arrangement of the bricks within themortar shifts as surfaces stretch, bend and twist,making them appear elastic.” This is particularlyapposite where “cut ‘n’ stick” or special bricks havebeen used to achieve the many acute angles anddifficult corners.

Structurally, the building’s loadbearing brickworksupports insitu concrete slabs. Exposed concrete soffitsare finished to a high standard and when viewed withthe brickwork, promote the primeval, enveloping feelthe architects wanted – a sort of urbane version of theprimeval church architecture of Sigurd Lewerentz(1885-1975). Perhaps more important are the benefitsof exposed masonry’s thermal mass, now regarded asone of the best constructions to moderate ourincreasingly higher solar heat gains and avoid the needfor air-conditioning.

What is particularly unusual about the brickwork isthat the architects have resisted the modernpreoccupation with structural expression. So, instead ofEnglish or Flemish bond brickwork, all 215 mmloadbearing internal walls simply comprise two 102 mm

skins of stretcher bond tied together. To complete thepicture, brick forms the floor finish throughout, butunlike the walls which were pressure-washed, the floorbrickwork has a milky veil that comes with using limemortar. Brickwork is therefore everywhere – althoughunlike Lewerentz’s St Peter’s in Klippan, Sweden (1966),it is not used as a ceiling.

Minimalism was not the architect’s intention whenthis gem of a building was conceived. Yet it is difficultto see it in any other way, given the purity and almostmonastic spatiality that has resulted. But irrespective ofpersonal interpretations, Brick House demonstrates justhow wonderful brick is when used as an internal finish,which was one of the reasons it got a special mentionin this year’s Brick Awards.For further information about this project, call theBDA on 01344-885651

Project teamArchitect Caruso St John ArchitectsStructural engineer Price & MyersServices engineer Mendick WaringQS Jackson ColesContractor Harris CalnanBrickwork Liberty Brickwork

BRICK BULLETIN ● 7

E

Opposite: Fairfaced

brickwork on walls and

floors combined with

the raw concrete

soffits produces a

minimalistic effect

Below: Double-skin

stretcher bond fairfaced

brickwork is used

throughout and can be

seen here in the stairwell

Above: The south

elevation of the auditorium

showing the main entrance

and fully glazed

double-height foyer

Right: The gatehouse’s

cellular arrangement

is expressed by a

600 mm deep brickwork

cladding zone. The main

entrance is denoted by a

cuboidal lantern over a

triple-height space

llies and Morrison is the latest architect tointerpret and continue Sir Denys Lasdun’soriginal 1958 masterplan for FitzwilliamCollege, Cambridge. The £8.2m contract

completed in 2004 has added two new buildings – agatehouse and an auditorium – that join a line up ofwork by Lasdun himself, MacCormack JamiesonPrichard, and van Heynigan and Haward.

Lasdun’s original intention was to create an enclosingwall of buildings that gravitated into the centre of thesite, thereby creating a series of garden spaces.However, due to the slow rate of land acquisition, hismasterplan could not be realised.

The construction of the gatehouse building andauditorium provides the college with a suitable mainentrance and creates a garden space that is bound onthree sides by the new buildings and on the fourth byan avenue of plane trees. Brick was specified for bothbuildings, reflecting its extensive use around the site.

Fronting Storey’s Way, the three-storey gatehouseincorporates a porter’s lodge and offices, with studentbedrooms on the upper two storeys. The burgundycoloured brick reflects Lasdun’s original colour choice.Structurally, the building’s load-bearing, cellular cross-wall construction is expressed externally by a 600 mmdeep cladding zone comprising 215 mm wide brick finsthat are punctuated at each storey level by a slender,highly polished concrete string course at seating level.Behind this 600 mm zone, the brickwork makes way forloadbearing blockwork and slab construction

The building is characterised by a heavier, moremassive use of brick on the ground floor, which makesway for the lighter brick construction of the upper twostoreys. This, according to Paul Appleton, director ofAllies and Morrison, “recalls the traditional order of aloadbearing brick building”. It also serves to allowtailoring of each facade according to orientation: withineach bedroom bay, the cell is expressed by a pre-formed weathered zinc window assembly bordered byopenable timber louvres.

Entering the gatehouse building is through a

three-storey high space topped by a cuboidal glasslantern. This grand entrance symbolism, which Appletonsays “establishes a major scale to the street andreflects the scale of trees in the courtyard”, iscomplemented by a Portland stone-faced section ofelevation that extends throughout the three storeys.

Once in the entrance hall, an axial shift aligns youwith a cloister formed by brick piers, which, if followedto its end, leads to a pleasant surprise.

For here, having emerged from the relative gloom ofthe gatehouse cloister, one gets the first glimpse of theauditorium. Here, the rational geometry of thegatehouse is replaced by the auditorium’s abstract feel– a sense that is heightened by the building’s use ofdelicious creamy buff brick. Aptly, surrounded on threesides by buildings, the auditorium, conceptually a E

A

Allies and Morrison’s award-winning gatehouse and auditorium atFitzwilliam College could teach us all a thing or two about buildingwith brick. Here, George Demetri makes a closer study

The practice rooms on the

western end of the

auditorium building are

expressed by a stainless

steel pod-like structure on

a brickwork base

ACAMBRIDGEEDUCATION

BRICK BULLETIN ● 9

E garden pavilion, itself becomes the dramatic centreof attention.

A long rectangle on plan, the building is partiallysubmerged into the ground so as not to overwhelm theneighbouring buildings. Conventional cavity walling withbrick facing is the main construction, although atopenings the underlying concrete structure is clearlymade visible. At either end, the plan is terminated incontrasting ways. On the eastern end lies a totallytransparent, double-height, partially louvred glass foyerthat extends across the width of the building. And onthe western end, a stainless steel-clad, pod-likestructure denotes the practice rooms on the first floor.In stating their function clearly and contrastingsuccessfully with the brickwork, both ends articulatethe building’s form.

Detailing the brickwork has let the designers expresstheir evident enjoyment of brick, for there is a greatdeal of variety, particularly at openings. The L-shaped

opening of the main entrance features a mass ofbrickwork that is seemingly supported by glass. Thiscontinues into the foyer where fairfaced finishes ofbrick, concrete, wood and Portland stone combine intoa harmonious whole that is enhanced by the externalbackdrop of attractively landscaped gardens.

Elsewhere, window openings are designed to revealthe depth of the walling, so windows are recessed in asdeeply as possible. Indeed, in the words of PaulAppleton, “the detail of openings in the brickworkencourages the impression of a fine-textured clothdraped over the structure”. The effect is particularlymarked with slit windows that are only two bricks wide.

If there is a criticism, it is reserved for the lostopportunity – no doubt on cost grounds – of a fewinches of water outside the glazed entrance foyer atthe eastern end of the building. The resulting reflectionwould have done more to enhance the building and theatmosphere of the garden overall than the ratherstrange rush-like planting that has been installed.

That said, both buildings constitute finecontemporary architectural statements that are all themore noteworthy because they are constructed out ofthe traditional material of brick. It should come as nosurprise therefore that this project was awarded BestPublic Building and BDA Building of the Year in the2005 Brick Awards.For further information about this project, call theBDA on 01344-885651

Project teamClient Fitzwilliam College, University of CambridgeArchitect Allies & MorrisonStructural and services engineer WhitbybirdQuantity surveyor Dearle and HendersonContractor Marriott ConstructionLandscape Cambridge Landscape ArchitectsBrickwork S Minett Brickwork Contractors

Right: Study bedrooms are

delineated by brick fins

and polished concrete

string courses; window

bays are in zinc flanked by

openable wooden louvres

Below: A brick cloister

connects the gatehouse

entrance to the auditorium

10 ● BRICK BULLETIN

ecent years have seen the skilled bricklayercome under increasing pressure fromprefabrication. But I built much the samebuilding in Britain (1994), the USA (1996) and

Continental Europe (2000), all with hand-laid brickwalls and glazed Roman-tiled roofs. Prior to this, in1989, my firm was commissioned to design over therailway at Blackfriars. Our little building headed a trainof projects that stretched to Holborn Viaduct. It was thebiggest planning application ever made to the City. Allthe architects were given a booklet describing thedeveloper’s philosophy and invited to annotate itsparagraphs. The effect of it was to entirely ban andprohibit hand laid brickwork.

No external scaffolding was to be used. Componentswere to be bought off the shelf. Structural framing wasinterchangeably steel or concrete, bought at the lastminute, according to the market. Cladding was to belightweight, prefabricated in as big pieces as possible,and hung, ready-glazed, off the columns and not thefloors. My frame, designed by the engineer who laterconceived the “wobbly” Millennium Bridge, bounced somuch it had 50 mm rubber joints in its pre-cast walls.The only finished interiors were the toilets, which weremade, complete, in steel site cabins by oil-rig yards inScotland and rolled into place, like Herculean building-blocks, on scaffold poles. We were told that these wereAmerican construction methods.

Yet my $17m American building site was populatedwith tightly unionised, well-paid craftsmen and women.It was my happiest on-site experience. Nobody wantedto replace them with prefab tat! The bricks were hand-laid off moveable, flying, scaffolds, like those still usedto clad New York’s skyscrapers. On the other hand, my£12m British site was populated with the usuallyproblematic crew. Still, even though my Texan siteagent called it a mess, the job came out well done.

I saw £25,000 of granite and glass crash off a cranehook onto the pavement on Aldgate, and noted thatthere were more security guards on Broadgate thansite workers. Pension funds never issued imperativeslike these; they normally encouraged fixed scaffolding,wrapped in polythene, and only revealed their projectsto the market when they were finished. I always knewmassive prefabrication wasted money. Stone

rainscreens on bouncy metal frames were defectswaiting to happen. This was not rational technology.

I told the developer his ends were financial and hismeans political. They abolished a political habit of theindustry – to take a big City of London project, wheretime is costly, and stop it while negotiating the terms ofemployment for the next 12 months. In contrast,prefabricating everything made site work unstoppable.

Unprecedentedly large City of London projectsbecame safe for investors. Short-term financeappeared. Scaffolding was prohibited. The frame couldbe thrown up and one wall “papered”, like a false-frontWild-West bank, with a totally clad exterior, completewith glazing. A pension-fund manager could, after a fewweeks of site work, stand in front and experience theseemingly finished product. The new, short term,finance used to launch the project could be exchangedfor more secure, less costly, long-term funding.

The overbearing project manager of our *7m Dutchproject refused to allow us to even meet the maincontractor. Our design was regarded as a Greek Templeor the work of the devil – the two were interchangeablefor Calvin. In fact it was just a shed with patterned brickcladdings and a glazed tile roof. The Dutch team madeprogramming mistakes that set completion back by160%. A major precasting gaffe by the concretecontractor was overlooked by the team. It was theworst building experience in my firm’s history.

Whole-building flat-slab prefabrication descends fromstate-subsidised housing programmes after WWII. It isnow misused, as Adolf Loos intended it to be, to abolishthe “ornamentor”. But who is he? He is a craftsmanwho signs the surface of a building with his ownhandiwork. The banishment of the site worker is usefulto our political establishment when it tries to providebuildings to service our needs, without making themstand for, or symbolise, anything that the worker, or thevoter, can recognise with pleasure. This imperative doesnot come from the USA. Whole-building prefabrication,and the abolition of handiwork cladding, comes fromthe Continental Europe of class war, fascism andcommunism that tore itself to shreds during the 20thcentury. It should have no place in Britain. John Outram is an architect and principal of JohnOutram Associates

VIEWPOINT

BRICK BULLETIN ● 11

R

Prefab is killing the brickieArchitect John Outram on why large-scale off-site constructionshould have no place in the modern British building industry

t is said that the people and town council ofAlton, in Hampshire, are very pleased withtheir new public library. They have everyreason to be. Completed in July 2004, the

development has provided this traditional Englishmarket town with a striking contemporary building thatnot only reflects Alton’s rural heritage but, at only£1.25m overall, represents excellent value for money.

Characterised by its glowing orange red brickwork,double-storey height piers and a steep clay roof pitch,the building is a contemporary reworking of localvernacular themes and was in fact conceived as a tithebarn. But what has resulted is an almost timeless,pared down, modern vernacular that would happily sit –and probably be just as popular – in any other Englishmarket town.

Hampshire County Architects designed the buildingas a replacement for the former library that occupiedthe site. As well as the requirement for the libraryservice to keep running throughout the constructionperiod, the architects had also to double the libraryspace provision. This has been achieved by spreadingthe open-plan accommodation over three levels, withthe ground floor acting as part library, entrance foyerand concourse for cross-cultural use. The upper twofloors provide more library space.

IA LIBRARYTO SHOUT

ABOUTThe latest newcomer to cause a

stir in the quiet market town of Alton in Hampshire is this

tithe-barn-style public library,which is earning praise for its

vernacular design and good value

Both CAD and card modelling were used in thedesign process, particularly to assess neighbourhoodimpact. With the building extending almost completelyto site boundaries and the architects’ choice of a 50°roof pitch as the most visually desirable, the resultingform took on a barn-like appearance. From then on, itwas a case of “sculpting” the building, as if from ahomogeneous block of marble. But marble was not thematerial used.

Project architect Martin Hallum explains: “It was

clear from the early building and contextual studiesthat brick would lend itself most favourably to theproposals. It was important that the brick was ‘soft’with a tactile quality and it was the handmade typebrick that best epitomised this characteristic.”

Standard cavity wall construction, with block innerleaf and a 100 mm partially insulated cavity clads thebuilding’s steel frame, which provides support andrestraint to the masonry. The south-facing frontelevation is a tightly controlled affair, with six slender6.5 m high piers creating a strong rhythm of openingsthat are partly screened by oak louvres. The samerhythm is replicated above by what appears to be aclerestory but is in fact a line of horizontal slit windowsthat provide desk-height lighting to study areas. With anod to traditional library detailing, openings generallyhave deep reveals that the architects chose to “givethe building a stature and a depth unmatched by manymodern materials and building methods”.

“Virtually all the aspects of the final building werecontrolled by the size of the uncut brick laid in simplestretcher bond,” adds Hallum, “with each elevationbeing meticulously tested to avoid awkward returnsand junctions.” To accentuate the rustic quality of thebrickwork, a recessed mortar joint was used.

Specifying natural materials that offer longevity andweather elegantly was clearly a guiding principlethroughout this scheme. Clay brick, combined with clayroof tile, western red cedar and European oak, havegiven this dignified yet very distinct little buildingwarmth and a real presence. They have also produceda building that, in the words of Martin Hallum, “is light,robust and a joy to touch”. For further information on this project, telephonethe BDA on 01344-88565

Above left: Oak louvres

restrict glare on the south

elevation and horizontal

slit windows above provide

lighting to reference areas

Left: Both CAD and card

modelling were used to

maximise site usage

and dictate the overall

tithe-barn form of the

building

Project teamClient Hampshire County CouncilArchitect Hampshire County Council ArchitectsStructural engineer RJ Watkinson AssociatesM&E Hampshire County Council Engineering ServicesContractor Richardsons (Nyewood)

BRICK BULLETIN ● 13

ost bricks are primarily chosen for theirappearance. However, where applications havespecific technical requirements, the suitabilityof any proposed brick should be checked by

reference to its physical properties as declared by themanufacturer. Durability is of paramount importance.

For masonry materials, durability does not refer torobustness, strength or resistance to wear or impact; itconcerns resistance to damage that might be caused byexposure to weathering of the finished masonry – inparticular, excessive wetness and freezing conditions.

In the United Kingdom and Ireland, bricks aremanufactured to conform to British Standards. BS 3921:Specification for Clay Bricks is still current, but is beingreplaced by the newly adopted European Standard BSEN 771-1: Specification for Clay Masonry Units. BS 3921will be withdrawn in April 2006, by which time other BSstandards and codes that deal with masonry will havebeen revised or amended to refer to BS EN standards.Bricks will remain the same and transition should notpresent problems because the old and new standardsdeal with measurement and classification of physicalproperties in a very similar manner, although thenomenclature differs and prescribed test methods arenot identical. With regard to durability, two propertiesare relevant:■ Resistance to damage by frost;■ Soluble salts content.

Resistance to damage by frostWhen choosing a brick for use in the external walls ofbuildings or in external works, such as boundary walls,it is essential to consider frost resistance.

If masonry materials are saturated with water andsubjected to cycles of freezing and thawing, thepressure caused by the formation of ice within thematerial may cause fracturing. The ability of the

material to resist damage depends on the interaction ofits strength and the size and continuity of its porestructure. Some fired clay materials are easily damagedwhereas others are very resistant.

The standards define three categories of frostresistance as shown in the table below.

Moderately frost-resistant (M or F1) bricks can beused for the external walls of many buildings. Suchwalls are vertical and most of the rain driven onto thewall surface by wind will be shed rapidly and so wettingwill normally be restricted to a few millimetres near theouter surface of the wall. Saturation is extremely rareprovided that the top of the wall and the wall areasbelow window openings are protected by roofoverhangs, projecting weathered copings and windowsills. Flush finished cappings and sills do not provideadequate protection. Moderately frost-resistant bricksare not suitable for the construction of copings andwindow sills themselves. Mortar joints with a recessedprofile should not be used with moderately frost-resistant bricks as they impede rainwater run-off andencourage wetting.

Wherever moderately frost-resistant bricks aresuitable, frost-resistant (F or F2) bricks can be used, butthey must be used if a design includes brickworksubject to saturation. The degree of exposure towetting is difficult to predict but, as common sense willconfirm, water stands on flat surfaces and will not runoff sloping surfaces as easily as from vertical ones.Brickwork forming such surfaces, such as brick-on-edgecappings and sills, together with the brickworkimmediately below, which receives water run-off, islikely to become very wet and often saturated andtherefore it is vulnerable to frost action. Frost-resistantbricks should be specified here.

For any building, check the various parts of thestructure and assess what exposure can be anticipated

TECHNICAL

UNDERSTANDINGIn this issue’s technical guide for specifiers, Mike Hammett looks

14 ● BRICK BULLETIN

M

Frost-resistance categories in British and European standards for bricks

Performance BS 3921 category EN 771-1 category Description of suitability Not frost-resistant O F0 Bricks suitable for internal use but if

used externally are liable to be damaged by frost action if not protected by impermeable cladding

Moderately frost-resistant M F1 Bricks durable except when in a saturated condition and subjected to repeated freezing and thawing

Frost-resistant F F2 Bricks durable in all building situations including those where they arein a saturated condition and subjected to repeated freezing and thawing

in the worst-case scenario, then specify a suitable brickfor that. It is impractical to specify different bricks forthe various parts of a structure on the grounds ofvarying frost resistance requirements. Any particularbrick product will have a frost resistance derived fromthe clay and the firing process and so it will not beavailable in alternative categories of durability to suitdifferent applications.

It has been extremely difficult to develop a testmethod that accurately reflects real experience of thefrost resistance of clay bricks in buildings, even aftermany years of work in this field. A test method for frostresistance is now recognised by the standards, but it isnot mandatory and a manufacturer’s declaration basedon evidence of established long term performance isaccepted as reliable, such as the moderately frost-resistant (M or F1) standard and the frost-resistant (F orF2) standard.

It is important to note that, despite popularassumption to the contrary, neither strength nor waterabsorption of a clay brick indicates its frost resistance.Furthermore, the definition of an engineering brickdoes not require it to be frost resistant. Frost resistanceis specified as a separate property.

Not-frost-resistant (O or F0) bricks are no longermade in the UK or Ireland. The F0 category in BS EN771-1 is for units that are not normally used in masonrysubject to weathering, such as perforated clay blocks.

Soluble salt contentClays from which bricks are made sometimes containsoluble salts that remain in the brick after firing. Fuelsburned during firing may also add more salts. In smallquantities these salts are harmless to properly fired

bricks, but soluble sulphates can damage cementmortar in brickwork exposed to long-term wetting.

Bricks are tested for soluble salt content inaccordance with the standards. Content is limited bydefined maximum percentages, by mass, of solublesalts. Two categories are defined in BS 3921 – normal(N) and low (L). The test method is not identical for theBS EN 771-1 categories, but in practice normal level (S1)and low content (S2) are equivalent to the N and Lcategories in BS 3921. In addition there is a “norequirement” (S0) category in BS EN 771-1, primarily torecognise that salt content is irrelevant for units usedin internal, dry locations.

Soluble salt content is significant when deciding whatmortar to use for brickwork. When bricks with normallevels of soluble salts (categories N and S1) are to beused for brickwork that is liable to be substantially wetfor prolonged periods, the mortar must be resistant to damage by sulphates – such as by the use ofsulphate-resisting Portland cement. In bricks with low soluble salt content (categories L and S2), thequantities are considered insufficient to constitute arisk to the mortar.

BRICK DURABILITYat what affects brickwork’s durability, and how to limit damage

BRICK BULLETIN ● 15

Further informationFor guidance on the appropriate brick durabilitycategories for a range of applications, see table 2 in the article “Understanding Brick Mortars”(Brick Bulletin, October 2004, page 15)■ A PDF version is downloadable fromwww.brick.org.uk/bulletin/PDF/bb_Oct_04.pdf

Moderately frost-resistant bricks (M or F1) can be used

where projecting eaves and sills protect against saturation

Flush windowsills demand frost-resistant bricks (F or F2)

16 ● BRICK BULLETIN

DIRECTORY The Brick Development Association’s member companies

Baggeridge Brick T 01902-880555F [email protected]

Blockleys BrickT 01952-251933F [email protected]

Bovingdon BrickworksT 01442-833176F [email protected] www.bovingdonbrickworks.co.uk

Broadmoor BrickworksT 01594-822255F [email protected]

Bulmer Brick & Tile CoT 01787-269232F [email protected]

Carlton BrickT 01226-711521F [email protected]

Charnwood Forest BrickT 01509-503203F [email protected]

Coleford Brick & Tile T 01594-822160F [email protected]

Dunton BrothersT 01494-772111F [email protected]

Freshfield LaneBrickworksT 01825-790350F [email protected] www.flb.uk.com

Hammill BrickT 01304-617613F [email protected]

Hanson BuildingProducts T 08705-258258F [email protected]

Ibstock BrickT 01530-261999F 01530-257457www.ibstock.co.uk

Kingscourt BrickT +353 (0)42-9667317F +353 (0)42-9667206

Michelmersh Brick & Tile T 01794-368506F [email protected]

Normanton Brick CoT 01924-892142/01924-895863F 01924-223455

Northcot BrickT 01386-700551F [email protected]

Ormonde BrickT +353 (0)56-41323F +353 (0)56-41314

Phoenix Brick CompanyT 01246-233223F 01246-230777www.bricksfromphoenix.co.ukenquiries@bricksfromphoenix.co.uk

Wm C Reade ofAldeburghT 01728-452982F [email protected]

Selborne Tile & Brick T 01420-478752F [email protected]

Swarland BrickT 01665-574229F [email protected]

Tyrone BrickT 02887-723421F 02887-727193www.tyrone-brick.com

The York HandmadeBrick CoT 01347-838881F 01347-838885 [email protected]

Wienerberger T 0161-485 8211F 0161-486 [email protected]

The Brick DevelopmentAssociationT 01344-885651F [email protected]

Stirling & Gowan’s Leicester Engineering Building (1963) is a brick tour de force

he work of Stirling & Gowan has beeninspirational to many architecture studentssince the 1950s. Characterised by a bold useof simple materials such as brick, tiles and

concrete, much of the practice’s work, particularly the Leicester University Engineering School (1963,pictured), helped to usher in a more expressive use ofmaterials away from orthodox modernist ideologies.

Surviving partner James Gowan, who at 83 continuesto practice as an architect, is as enthusiastic aboutbrick as a contemporary material of construction as hewas back then. “Brick is very versatile and economical,”he says. “Although modular, it can be halved like achild’s friable toy and can adapt to a wide range ofshapes and plans. Brick gives a great deal of freedomand is just the right weight for a workman to handle. I have used it on many projects.”

After the split with Stirling, one of Gowan's firstprojects was to design a house near Hampstead Heathfor the Schreiber family. “I recently revisited this houseand the brickwork is still absolutely splendid,” heexplains, adding: “The engineering bricks and recessedjoints have lasted terribly well.” Just another exampleof the aesthetics and longevity of brick, then.

The contents of this publication are intended for general guidance only and any person intending to use these contents for the purpose of design, construction or repair of brickwork or any related project should firstconsult a professional adviser. The Brick Development Association, its servants, and any persons who contributed to or who are in any way connected with this publication accept no liability arising from negligence orotherwise howsoever caused for any injury or damage to any person or property or as a result of any use or reliance on any method, product, instruction, idea or other contents of this publication.

TStill going strong …