The Missouri Nurses Association & American Nurses Association

2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An]...

Transcript of 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An]...

![Page 1: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/1.jpg)

WENDY BENBOW AND GILL JORDAN

2015–16

The 2015–16 edition of A Handbook for Student Nurses has been brought completely up to date to incorporate the revised 2015 NMC Code, new NMC guidance on raising concerns and on using social media, the duty of candour, and other recent developments in the health service. References have also been comprehensively updated.

The book provides an introduction to the essential background knowledge that pre-registration nursing students need as a foundation for their training. It covers the core of first year nursing studies:

• Legal and professional issues • Communication • Values and health care ethics • Reflection and personal development • Evidence-based practice • Study skills • Medicine, IV fluid and drug administration

Case studies and examples, activities and reflectionpoints all aid learning, while references to legislation,key documents and reports, and website links to relevantorganisations provide easy access to core information.

A Handbook for Student Nurses is widely recommended in institutions across the UK and is essential reading for new students.

What lecturers think about this book:

“I found this to be an excellent resource and I feel students new to the profession would find it extremely useful…. The book is well-organised,

highly readable and accessible.”

“An excellent introductory text for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.”

“[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information

for pre- and post-registration nursing students.”

“This is an excellent book, full of relevant information

for student nurses.”

STUDENT NURSESI N T R O D U C I N G K E Y I S S U E SR E L E VA N T F O R P R AC T I C E

A HANDBOOK FOR

2015–16 EDITION

9 781908 625359

ISBN 978-1-908625-35-9

BENBOW &

JORDANA H

ANDBO

OK FO

R STUDENT N

URSESR E L AT E D T I T L E S :

www.lanternpublishing.co.uk

![Page 2: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/2.jpg)

2 015 –16 E D I T I O N

![Page 3: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/3.jpg)

O T H E R T I T L E S F R O M L A N T E R N

9781908625151

9781908625243 9781908625014 9781908625021 9781908625175

9781908625328 9781908625281

F o r mo r e de t a i l s s e e w w w. l an t e r npub l i s h in g .c om

A HANDBOOK FOR

STUDENT NURSESI N T R O D U C I N G K E Y I S S U E S R E L E VA N T F O R P R AC T I C E

2 015 –16 E D I T I O N

WENDY BENBOW AND GILL JORDAN

![Page 4: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/4.jpg)

A HANDBOOK FOR

STUDENT NURSESI N T R O D U C I N G K E Y I S S U E S R E L E VA N T F O R P R AC T I C E

2 015 –16 E D I T I O N

WENDY BENBOW AND GILL JORDAN

![Page 5: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/5.jpg)

ISBN 978 1 908625 35 9

First edition published in 2009 by Reflect Press Ltd (ISBN 9781906052195)

Second edition published in 2013 by Lantern Publishing Ltd (ISBN 9781908625144)

2015–16 edition published in 2015 by Lantern Publishing Ltd

Lantern Publishing Limited, The Old Hayloft, Vantage Business Park, Bloxham Rd, Banbury, OX16 9UX, UK

www.lanternpublishing.com

© 2015, Wendy Benbow and Gill Jordan

The right of Wendy Benbow and Gill Jordan to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

www.cla.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The authors and publisher have made every attempt to ensure the content of this book is up to date and accurate. However, healthcare knowledge and information is changing all the time so the reader is advised to double-check any information in this text on drug usage, treatment procedures, the use of equipment, etc. to confirm that it complies with the latest safety recommendations, standards of practice and legislation, as well as local Trust policies and procedures. Students are advised to check with their tutor and/or mentor before carrying out any of the procedures in this textbook.

Typeset by Medlar Publishing Solutions Pvt Ltd, IndiaCover design by Andrew Magee Design LtdPrinted in the UKDistributed by NBN International, 10 Thornbury Rd, Plymouth, PL6 7PP, UK

![Page 6: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/6.jpg)

CONTENTS

Preface vii

About the authors viii

1 Nurse education and mentorship 1

2 Communication 19

3 Legal and professional issues 33

4 Values and health care ethics 61

5 The UK as a culturally diverse society 77

6 Quality assurance 99

7 Evidence-based practice 123

8 Interprofessional practice and changing roles in nursing 139

9 Reflection and professional development 159

10 Study skills and information technology 177

11 Medicine, IV fluid and blood administration 201

Index 245

![Page 7: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/7.jpg)

![Page 8: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/8.jpg)

PREFACE

The NMC is responsible for setting standards of proficiency that define the overarching principles of being able to practise as a nurse, and must be achieved before students are eligible to join the register. The aim of this handbook is to highlight and address many of the key issues which sur-round these standards of proficiency and relate them to working knowledge you require in the practice setting.

The handbook has been written primarily for student nurses, return to prac-tice nurses and those who trained overseas, but it is envisaged that students undertaking Further Education access courses and NVQ/QCF (health care) qualifications will also find the information helpful. The content is also rel-evant for Health Care Assistants and Assistant Practitioners.

The information within the book is relevant to all areas of nursing, and all fields of nursing. It is designed so that you can utilise individual chapters as a quick source of reference, although along with the activities and further reading, it may serve as a starting point for more in-depth study. Where websites are identified, these are only suggested sources of further infor-mation and others may be found through general search engines such as Google. Although the emphasis is mainly related to healthcare in England, we do refer to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland when appropriate.

Wendy Benbow and Gill JordanJune 2015

vii

![Page 9: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/9.jpg)

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Following qualification as a registered nurse in 1969, Wendy Benbow worked for two years in genito-urinary surgery and major spinal injuries before moving into community nursing. Over a 14-year period Wendy was involved in a variety of roles that included community nursing sister, prac-tice work teacher and nurse manager, as well as time seconded for research and co-ordinating pre-registration student placements for the local acute hospital.

After a year out to complete her teaching qualification, Wendy began work-ing full-time in education in 1985. She was involved in both teaching on and managing a range of pre- and post-registration courses, programme development, regionally funded research and national project development. She has now retired from working in healthcare.

On qualifying as a registered nurse in 1978, Gill Jordan completed her Ortho-paedic Nursing Certificate and moved to New Zealand where she worked in a large orthopaedic teaching hospital, ultimately as a ward sister of a trauma orthopaedic ward.

On her return to the UK in 1988, Gill moved into nurse education. Since then, she has been involved in a variety of courses and professional development programmes, as both a teacher and programme leader. These have included courses leading to professional registration, Return to Practice, Overseas Nurses Programme, conversion courses and various post-registration under-graduate programmes.

viii

![Page 10: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/10.jpg)

0�3LEgAL ANd PROFESSiONAL iSSUES

The aim of this chapter is to make you aware of the legal and professional issues surrounding nursing.

• demonstrateanawarenessofthelegalframeworkwithinwhichcareisprovided;

• discussthelegalresponsibilitiesofnurseswhencaringforpatientsorclients;

• definetheterm‘accountability’inrelationtoTheCode: Professional Standards of Practice and Behaviour for Nurses and Midwives (NMC,2015)andotherguidelinesissuedbytheNursingandMidwiferyCouncil.

Learning Outcomes

Oncompletionofthischapteryou

shouldbeableto:

You may not feel that all the considerations discussed in this chapter apply to you as you are not yet a Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) regis-trant. However, as a citizen or resident of the United Kingdom (UK) the legal aspects do apply (under both criminal and civil law). In addition you are advised to look on the NMC regulations as a guide for best practice. Any employment regulation may affect you when undertaking clinical practice and you should also be aware of any charters, guidelines, policies, etc. that your university or college and/or placement organisation asks you to respect.

Accountability‘To be accountable is literally to be liable to be called upon to give an account of what one has done or not done’ (Banks, 2004, p. 150). The importance of accountability in professional life is not new, but there is an increasing focus on issues around nursing accountability and nurses, both registered and in preparation for registration, must be aware of its implications.

33

![Page 11: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/11.jpg)

A Handbook for Student Nurses

34

Accountability is often defined as responsibility, but there is a difference between the two. Responsibility is concerned with answering for what you do, whereas accountability is being answerable for the ‘consequences’ of what you do. The most important factor in accountability is that it is ‘personal’ and no other registered nurse can be accountable for another. Before regis-tration you are not professionally accountable in the way that you will be after registering with the NMC; however, the NMC states that as a student you must conduct yourself professionally and in alignment with The Code.

Castledine (1991) offers a further definition of accountability which encom-passes the whole ethos of how accountability in nursing should be viewed. He states that accountability is:

‘thatspecialphenomena[sic]relatedtonursingpracticewhichnursesareentrustedwith,areanswerablefor,takethecreditandtheblamefor,andcanbejudgedwithinlegalandmoralboundaries’.

Castledine(1991,p.28).

This chapter explores those legal boundaries.

Arenas of accountability

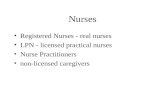

As you can see from Figure 3.1, Dimond (2011), a barrister who has a great interest in professional accountability and patients’ rights, believes there are four arenas of accountability which nurses must consider.

Criminal law and the courts

In criminal law, a crime is committed against the state either when an act is performed that the law forbids, or when an act is omitted that the law requires. For a conviction it must be proved that a person intended to

PublicCriminal Law

Criminal Courts

PatientCivil Law

Civil Courts

ProfessionNMC: The Code NMC: Fitness to Practise Panels

EmployerContract of EmploymentEmployment Tribunal

Professional

Figure 3.1 – Arenas of accountability (adapted from Dimond, 2011)

![Page 12: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/12.jpg)

Chapter 3: Legal and professional issues

35

commit the crime, or was reckless in doing the criminal act. More serious cases include murder, manslaughter and rape (all of which nurses have been found guilty of) and are heard in a Crown Court before a judge and jury. Lesser cases (such as driving offences) are heard in a magistrates’ court. The outcome of prosecution is a custodial sentence or a fine, or both.

Civil law and the courts

This part of the law involves the rights and duties individuals have towards each other. Legal action can be taken by a private individual against another individual or an organisation. This is the main area which affects nurses and which lawyers refer to as the law of torts. The outcomes from these cases usually involve awards of compensation (for damages) or orders (injunctions) to stop an individual acting unlawfully. The NMC recognises that this is an area where nurses are increasingly being involved and states that nurses must have an indemnity arrangement which provides appropri-ate cover for their practice (NMC, 2015, Section 12.1).

Dutyofcare(negligence)

An action for negligence is a civil action, and results from a breach of duty of care. A nurse may be held legally liable if it can be shown either that they have failed to exercise the skills properly expected of them, or that they have undertaken tasks that they are not competent to perform (Dimond, 2011).

For negligence to be proved the following conditions must be satisfied:1. A duty of care is owed by the defendant (nurse) to the claimant

(patient) i.e. the nurse / patient relationship (duty);2. There is a breach in the standard of care owed (breach);3. This breach has caused reasonably foreseeable harm (causation);4. This breach has caused harm, either by action or omission.

Some criminal cases may also have a civil action brought if any harm has been caused by ‘action or omission’.

• Thinkofacircumstancewhereanursemightbeheldcriminallyliable(i.e.acriminalactthatanursemightcommit).

• Thinkofcircumstancesinclinicalpracticewhereanursemightbejudgednegligent(i.e.performanactthatcouldbereferredtoacivilcourt).

A C T i v i T y 3 .1

![Page 13: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/13.jpg)

A Handbook for Student Nurses

36

Accountability to the employer

Everyone in a nursing role is accountable to their employer. There is an implied term in every contract of employment that the employee will obey the reasonable instructions of the employer (i.e. follow any policies, proce-dures, standards, etc.), and that any employee who breaches their contract may be subject to disciplinary action. Even though, as a student nurse, you are not ‘employed’ by a placement organisation as such, you are still bound by their ‘instructions’, and any deviation from these could lead to disciplinary action by your university and/or your placement provider. You must therefore be familiar with the policies, procedures, etc. of your place-ment provider, as you could be called to account by your university or by the law.

Vicariousliability

An employer is liable for any actions committed by his/her employees (for example nurses) during the scope of their employment. The employer (for example, an NHS Trust or a care home) cannot shirk this liability by saying it provides competent, trained staff – it will always be primarily responsible for any negligence to patients by their staff (Dimond, 2011).

However, this does not remove any legal responsibility / accountability from the nurse. If a patient takes a civil action against a hospital (for example, for damages caused by one of its employees), and the hospital is found directly liable by the civil courts, the hospital as the employer could in turn take legal action against the employee. This usually happens when a hospital (an employer) has to pay compensation to a patient as a result of an employee’s negligence, and tries to recoup their money from the employee. As this falls in the arena of civil law, which applies to all citizens and residents of the UK, this could affect you as a student nurse.

Professional liability – the Nursing and Midwifery CouncilThe core function of the NMC is to establish standards of education, train-ing, conduct and performance for nursing and midwifery and to ensure those standards are maintained, thereby safeguarding the health and well-being of the public. The powers of the NMC are set out in the Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001. Although you are a student nurse, you are already affected by the role of the NMC as it sets the standards of education and

![Page 14: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/14.jpg)

Chapter 3: Legal and professional issues

37

training you are undertaking. The NMC determines the level of entry and content of pre-registration nursing programmes, and universities have to have validation from the NMC to run such programmes. Programmes are also monitored and reviewed by the NMC on a regular basis.

The NMC’s key tasks are to:

• safeguard the health and wellbeing of the public;

• set standards of education, training and conduct so that nurses and midwives can deliver high quality healthcare consistently throughout their careers;

• ensure nurses and midwives keep their skills and knowledge up to date and uphold professional standards;

• have clear and transparent processes to investigate nurses and midwives who fall short of standards.

(NMC, 2014)

All nurses working in a registered nurse capacity must be registered with the NMC. When you have successfully completed your nursing programme your university will notify the NMC that you have met the required standards and that you are eligible for entry on the register. Your course director will also complete a Declaration of Good Health and Good Character on your behalf, which must be received by the NMC before registration can take place.

What constitutes good health and good character?

Good health and good character are fundamental to fitness to practise as a nurse.

Good health means that you must be capable of safe and effective prac-tice without supervision. It does not mean the absence of any disability or health condition. Many disabled people and those with health condi-tions are able to practise, with or without adjustments to support their practice.

Long-term conditions such as epilepsy, diabetes or depression can be well managed and would not be incompatible with registration. Equally, tempo-rary health conditions do not necessarily mean a person is not fit to practise. For example, having a broken leg may mean a person is not fit to work for a period of time. It does not mean they are not fit to practise as they can reasonably expect to recover fully and return to work.

![Page 15: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/15.jpg)

A Handbook for Student Nurses

38

Good character is important as nurses and midwives must be honest and trustworthy. Your good character is based on your conduct, behaviour and attitude. It covers examples such as someone who knowingly prac-tises as a nurse before they are on the register, or someone who signs a student off from an educational programme while being aware of poor behaviour.

It also includes any convictions and cautions that are not considered com-patible with professional registration and that might bring the profession into disrepute. Your character must be sufficiently good for you to be capa-ble of safe and effective practice without supervision (NMC, 2010).

Guidance on professional conduct for nursing and midwifery students

The NMC acknowledges that as a student you will come into close contact with patients, by observing care being given, by helping to provide care and, towards the end of your course, through full participation in providing care. As a student nurse you are bound by The Code: Professional Standards for Practice and Behaviour of Nurses and Midwives (NMC, 2015) and must conduct yourself professionally at all times. Additionally, the NMC empha-sises that you must “raise concerns immediately if you are being asked to practise beyond your role, experience and training” (NMC, 2015, Section 16.2); and “ask for help from a suitably qualified and experienced health-care professional to carry out any action or procedure that is beyond the limits of your competence” (NMC, 2015, Section 13.3).

Adherence to the NMC Code is important not just in the clinical setting, but also in your university or college. In addition most universities will ask you to sign a Code or Charter which would include expectations that you would:

• take responsibility for your own learning;

• follow the policy on attendance as set out by your university and clinical placement provider;

• follow the policy on submission of coursework and completion of clinical assessments as set out by your university and clinical placement provider;

• reflect on and respond constructively to feedback you are given;

![Page 16: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/16.jpg)

Chapter 3: Legal and professional issues

39

• endeavour to provide care based on the best available evidence or best practice;

• not plagiarise or falsify coursework or clinical assessments.

The Code: Professional Standards of Practice and Behaviour for Nurses and Midwives (NMC, 2015)

Once registered, you must be aware of the professional accountability you will automatically assume. The NMC stresses the need for all reg-istered nurses to be personally accountable for their practice by issuing them with The Code: Professional Standards of Practice and Behaviour for Nurses and Midwives (NMC, 2015). Although this document is not part of law, the functions of the NMC include a requirement to establish and improve standards of professional conduct (Health Act, 1999; Nursing and Midwifery Order, 2001), and they do this by issuing The Code and a requirement for all registered nurses to abide by it. Breaching The Code is in effect a breach of registration and may lead to the removal of the nurse’s name from the register.

Paramount in The Code is the requirement for registered nurses to have ‘the knowledge and skills for safe and effective practice’ (NMC, 2015, Section 6.2). In line with this the NMC warns that careful consideration must be made of professional accountability if nurses are asked to work in an area for which they are not adequately prepared – being open about their limitations is not a sign of weakness but rather a key indicator of mature and caring practice (Richards and Edwards, 2008).

The Code is divided into four themes with a number of subsections under each theme:

• Prioritise people;

• Practise effectively;

• Preserve safety;

• Promote professionalism and trust.

This code of conduct should be considered together with the Nursing and Midwifery Council’s rules, standards, guidance and advice, available from www.nmc-uk.org.

![Page 17: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/17.jpg)

A Handbook for Student Nurses

40

Delegation

Although all registered nurses are personally accountable for their prac-tice, there may be some instances where nurses may be delegated tasks, or indeed delegate tasks themselves.

The NMC has a section in The Code (NMC, 2015, Sections 11.1–11.3) outlin-ing the considerations nurses must take before delegating:

• Only delegate tasks and duties that are within the other person’s scope of competence, making sure they fully understand your instructions;

• Make sure that everyone you delegate tasks to is adequately supervised and supported so they can provide safe and compassionate care; and

• Confirm the outcome of any task you have delegated to someone else meets the required standard.

This second clause could affect you if you believe that a registered nurse has delegated you a task and is not supporting or supervising you. As mentioned before, as a student, you must recognise and stay within the limits of your competence and work only under the supervision and support of a qualified professional and ask for help from your mentor or tutor when you need it.

Peate (2012) reminds registered nurses of the legal perspective of delegation, and believes that when delegating a task the following must be borne in mind:

• when working as a team member you are personally accountable for your own actions or omissions – there is no such concept as team negligence. If harm occurs, you are individually accountable;

• you must make it known and obtain help and supervision from a competent practitioner if you feel an aspect of practice lies beyond your level of competence or outside your area of registration.

As previously identified, The Code (NMC, 2015) is divided into sections. The following pages look at some of the issues The Code raises in more detail, those of consent, confidentiality, record keeping and maintaining profes-sional knowledge and competence.

ConsentEvery mentally competent adult has the right in law to consent to any touch-ing of his/her person, or to refuse any examination or treatment. If he/she is touched without consent or other lawful justification, then the person has

![Page 18: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/18.jpg)

Chapter 3: Legal and professional issues

41

ObtainacopyofThe CodefromtheNMCwebsite(www.nmc-uk.org).ReaditandthenreadthefollowingarticleandidentifythesectionsofThe Codeyouthinkthisnursebreached–theanswersareintheconclusionattheendoftheactivity.

(Reproduced with permission from British Journal of Nursing)

Staff nurse who failed to provide adequate nursing care for patientsBritish Journal of Nursing,2004,Vol.13,No7:389ProfessionalMisconductSeries

InthefollowingcaseaseniornursecalledJodeliberatelyignoredcertainaspectsofcarewhileonnightdutybecauseshefeltthatitwasnotherresponsi-bilitytocarryoutcertaintasksortocheckthattheyhadbeendone.

Joworkedonnightsforalargeinner-cityhospitaltrustandhadbeendoingsoforover10years.Whenworkingonthegeneralmedical/surgicalwardsshewasoftenheardtosayderogatoryremarksaboutsomeofthepatientsorcorenurs-ingtasksshewasexpectedtodo.Forexample,shesawitasajuniornursingroletogoroundandattendtopatients’pressureneeds.Shefeltherexpertiselayingivingoutdrugs,managingintravenousinfusionlinesanddoingcertainnursingprocedures.

Ontheparticularwardwhereshewasworkingtwopatientsrequestedpainrelief.Jodidnotbothertogoandseethepatients,butinstructedtwohealth-careassistantswhowereondutywithhertogiveeachofthepatientstwoparacetamoltablets.Thehealthcareassistantsgavethemedicationtothepatientsasdirected,butatnotimedidJoattempttocheckwhattheyhadgivenortoclarifywiththepatientshowtheywerefeeling.Thesituationcontinuedforseveralshifts.AnypatientwhorequiredadditionalpainreliefwasreferredbythehealthcareassistantstoJo,whotoldthemtogiveparacetamol.

OnthelastoccasionthatJoandthehealthcareassistantswereondutytogether,anagencynursewasalsopresentbecauseoftheworkloadontheward.How-ever,Jostilldidnothelpunlessshefeltitwasabsolutelynecessary.Atonetimeduringtheeveningsheleftthewardforabreakstatingthatshehadleftthekeysontheshelfintheoffice.Thesekeysincludedkeystothecontrolleddrugcup-boardandthedrugstrolley.AlthoughJowasentitledtoabreakfromtheward,thiswasthethirdshehadtakenthatnightandshedidnottellthestaffwhereshewasgoing.

TheagencynursewasangrythatJohadleftthewardwithoutinformingherofwhereshewasgoingandhowshecouldbecontacted.Joalsodidnottellthe

A C T i v i T y 3 . 2

![Page 19: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/19.jpg)

A Handbook for Student Nurses

42

agencynursewhereshecouldfindthekeys.Apatientthencomplainedofpainandthehealthcareassistantaskedtheagencynurse,whowasaregisterednurse,ifshecouldgivethepatientsomeparacetamol.Theagencynursethenquestionedthehealthcareassistantsabouttheproceduretheyhadbeenfollow-ingwithJo.

WhenJoeventuallyreturnedtotheward,theagencynursechallengedheraboutthedrugadministrationandleavingthekeysinthewardoffice.Jowasoffhandwiththeagencynurseanddidnotspeaktoherfortherestoftheshift.Atthehandovertothedaystaff,Jogavethereportwithoutinvolvingtherestofthenightnursingteam.Sheletthehealthcareassistantsandtheagencynursewriteupthenursingrecords,butatnotimeinthehandoverdidsheinvolvethemintheverbalreport.

Theagencynursecomplainedtothewardmanagerabouttheincidentsthathadoccurred,andalsosomeproblemsrelatingtoabloodtransfusionthatJohadbeenmanaging.ItappearedthatJohadnotfollowedthetrustprotocolwithregardtoadministrationofatransfusion.TherehadbeenalongdelaybeforeithadbeencommencedandJohadnotrecordedanyobservationsofthepatientduringthetransfusion.

ConclusionAninvestigationwascarriedoutbytheTrustanditwasfeltthatJoshouldbedismissedfromherpostandhercasereferredtotheNursingandMidwiferyCouncil.JowaschargedbytheNMCandfoundguiltyof:

• failingtoprovideadequatesupportforpatientsonaward;

• givingmedicationtohealthcareassistantstoadministertopatients;

• leavingawardwithoutadvisingstaffofherwhereabouts,andnothandingoverthewardkeystoaregisterednursecolleague;

• failingtoprovideanadequateandappropriatehandoverofpatientcare;

• failingtofollowthecorrectprotocolandprocedurewhileadministeringabloodtransfusion.

Hernamewasremovedfromthenursingregister.

Note:thiscaseispartofaseriesbasedontruecaseswhichwerereportedtotheNMC.

A C T i v i T y 3 . 2 c o n t i n u e d

![Page 20: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/20.jpg)

Chapter 3: Legal and professional issues

43

the right to bring a criminal action for battery, or a civil action for trespass to the person (Dimond, 2011). Furthermore, should harm occur to the patient, it could result in a legal action against the nurse for negligence. Consent also affirms the person’s right to self-determination and autonomy (Caulfield, 2005). Lord Donaldson, once the second most senior judge in England and Wales, pointed out that consent is twofold – first to obtain ‘legal’ justification for care (as above), and secondly ‘clinical’ consent to secure the patient’s trust and co-operation.

The NMC Code states that you must make sure that you get informed consent and document it before carrying out any action (NMC, 2015, Section 4.2), and that any information you give a patient so that they can make an informed decision should be accurate and truthful and presented in such a way as to be easily understood.

Consent can be written, verbal or implied (‘by co-operation’). They are all equally valid. However, they vary considerably in their value as evidence in proving that consent was given. Consent in writing is the best form of evidence and therefore is the preferred method for patients when any procedure involv-ing some risk is contemplated. As a student you would not be expected to give information to patients about their condition or treatment or to obtain any writ-ten consent. However, any form of nursing intervention requires the patient’s consent and it is good practice to:

• make sure people know that you are a student;

• ensure that you gain their consent before you begin to provide care;

• respect the right for people to request care to be provided by a registered professional.

It is a basic principle of law in this country that a mentally competent adult has the right to refuse treatment and take his or her own discharge contrary to medical advice. The NMC (2015, Section 4.1) supports this by stating that you must ‘balance the need to act in the best interests of people at all times with the requirement to respect a person's right to accept or refuse treatment’.

Consent must be:

• given by a legally competent person;

• informed;

• given freely.

![Page 21: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/21.jpg)

A Handbook for Student Nurses

44

A legally competent person

The person giving consent must have the capacity to do so. A legally compe-tent person must be able to understand and retain information and use the information to make an informed decision. You must presume that a patient is competent unless otherwise assessed by a suitably qualified practitioner. The assessment of whether an adult lacks the capacity to consent is made by the cli-nician providing treatment or care, but it should involve nurses’ views as well.

No one has the right to consent on behalf of another competent adult. Fur-ther, it is accepted that adults over the age of 16 have the relevant capacity to understand and make their own decisions about medical and nursing treatment (Caulfield, 2005).

Adults temporarily unable to consent

In emergency situations where an adult becomes unable to consent (for example, if they are unconscious), the law allows treatment as long as it is ‘in the patient’s best interests’. Medical intervention that can be delayed until the patient can consent should be delayed (exceptions to this are if the person has issued an advanced directive refusing treatment, in which case the treatment is not given). In ‘the patient’s best interests’ is said to be when a ‘body of other similar treatment providers would also give the same treatment’ (Tingle and Cribb, 2007, p. 168), and arises from a court case in 1989 (F. v. West Berkshire Health Authority).

Informed consent

The patient must be able to give informed consent to the proposed treat-ments, and the information given by any health care professional (including registered nurses) should include any material risks such as the nature and consequences of the proposed treatment, the consequences of not having the treatment and any alternatives to the treatment.

Given freely

Consent must be given freely – this means that no threats or implied threats must be used, that no ‘coercion and undue influence’ is applied. Coercion invalidates consent, and if a nurse feels that the patient is being coerced, either by another health care professional or by a family member, they should seek to see the patient alone to ascertain that their wishes are being adhered to (Peate, 2012).

![Page 22: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/22.jpg)

Chapter 3: Legal and professional issues

45

Children and young people

If the patient is under 18 years old (age of consent) the rules concerning consent for medical treatment are different. A person aged 16–17 is allowed to consent to treatment under the Family Law Reform Act (1969), in a simi-lar way to an adult. However, refusal of treatment can be overridden by a person with parental authority or a court order until they are 18 years old.

A person under the age of 16 years, who has sufficient understanding and intelligence to enable them to understand the proposed treatment or inves-tigation may have the capacity to consent (Department of Health, 2009). Children who have these capacities are said to be ‘Gillick competent’. The term Gillick (sometimes referred to as ‘Fraser’ after the judge who heard the case) comes from a court case in 1985 which concerned a teenage girl’s right to consent to medical treatment without her parents’ knowledge (Gillick v. West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health Authority).

An assessment to determine whether a minor is Gillick (Fraser) competent must consider the following questions (Peate, 2012, p. 75):

• Does the child understand the proposed treatment, his/her medical condition, and the consequences that may emerge if he/she refuses or agrees to treatment?

• Does he/she understand the moral, social and family issues involved in the decision he/she is to make?

• Does the mental state of the child fluctuate?

• What treatment is to be performed? Does the child understand the complexities of the proposed treatment and the potential risks associated with it?

Mental Capacity Act (2005)

The Mental Capacity Act affects people living in England and Wales over the age of 16. It is concerned with protecting people who lack the capacity to make their own decisions about a variety of health and social circumstances.

The Act includes:

• a test to determine ‘a person’s best interests’;

• Lasting Powers of Attorney that extend to a person’s health and welfare as well as property and money;

![Page 23: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/23.jpg)

A Handbook for Student Nurses

46

• a Court of Protection and an office of Public Guardian to support the Court;

• deputies who can make decisions in the ‘person’s best interests’;

• a criminal offence of ill-treatment and neglect;

• regulation of advance decisions to refuse treatment;

• regulation of research in relation to individuals who lack mental capacity;

• an Independent Mental Capacity Advocate service (IMCA) for people with no family or friends;

• a Code of Practice to accompany the Act – health care professionals have a duty to abide by the Code.

Underlying principles of the Mental Capacity Act (2005)

• A presumption of capacity: everyone has the right to make their own decisions, so a person must be assumed to have capacity unless it is established that they lack capacity.

• Individuals should be supported where possible so that they can make their own decisions: a person must not be treated as being unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to help them to do so have been taken, without success.

• People have the right to make decisions which may seem eccentric or unwise to other people: a person is not to be treated as unable to make a clear decision merely because he or she makes an unwise decision.

• Best interests: acts done or decisions made on behalf of a person established to be lacking capacity must be in their best interests.

• Rights and freedoms must be restricted as little as possible: before doing an act or taking a decision on behalf of a person, regard must be had as to whether the purpose underlying that act or decision can be achieved in a way that is less restrictive of his rights or freedom of action.

Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS)

The Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) are part of the Mental Capac-ity Act (2005). They aim to make sure that people in care homes, hospitals and supported living are looked after in a way that does not inappropriately restrict their freedom.

![Page 24: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/24.jpg)

Chapter 3: Legal and professional issues

47

A deprivation of liberty occurs when ‘the person is under continuous super-vision and control and is not free to leave, and the person lacks capacity to consent to these arrangements’ (Department of Health, 2014).

The safeguards apply to vulnerable people aged 18 or over who have a mental health condition (this includes dementia), who are in hospitals, care homes and supported living, and who do not have the mental capacity (ability) to make decisions about their care or treatment.

The Mental Capacity Act (2005) says that someone who lacks mental capac-ity cannot do one or more of the following four things:

• understand information given to them;

• retain that information long enough to be able to make a decision;

• weigh up the information available and understand the consequences of the decision;

• communicate their decision – this could be by any possible means, such as talking, using sign language or even simple muscle movements like blinking an eye or squeezing a hand.

The key elements of the safeguards are:

• to provide the person with a representative;

• to give the person (or their representative) the right to challenge a deprivation of liberty through the Court of Protection;

• to provide a mechanism for deprivation of liberty to be reviewed and monitored regularly.

These safeguards do not apply when someone is detained (‘sectioned’) under the Mental Health Act 1983.

Any assessment must be made by at least two assessors – a best inter-ests assessor and a mental health assessor, neither of whom is involved in that person’s care or in making any decisions about it. The best interests assessor will be a qualified social worker, nurse, occupational therapist or chartered psychologist with the appropriate training and experience. The mental health assessor must be a doctor (likely to be a psychiatrist or geri-atrician). If the assessment determines that a deprivation of liberty would be in the person’s best interests, the Local authority (in England) will grant an authorisation.

![Page 25: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/25.jpg)

A Handbook for Student Nurses

48

Everyone who is subject to an authorised deprivation of liberty must have a ‘relevant person’s representative’ to speak for them. The representative is appointed by the supervisory body authorising the deprivation. Often it will be a family member or friend, or other carer, and they would normally have been involved in the assessment. The representative can gain access to documents about the decision and ask for a review of the decision, and should be informed if anything changes.

If the person has no immediate family or non-professional carer to sup-port them, the supervisory body will appoint a representative. This may be an independent mental capacity advocate (IMCA). The representative must stay in touch with the person deprived of their liberty in order to fulfill their role and to protect the rights of that person.

There have been several test cases in the European Court of Human Rights and in the UK that have clarified which situations may constitute a depriva-tion of liberty:

• a patient being restrained in order to admit them to hospital;

• medication being given against a person’s will;

• staff having complete control over a patient’s care or movements for a long period;

• staff making all decisions about a patient, including choices about assessments, treatment and visitors;

• staff deciding whether a patient can be released into the care of others or to live elsewhere;

• staff refusing to discharge a person into the care of others;

• staff restricting a person’s access to their friends or family.(www.alzheimers.org.uk)

Advance decisions to refuse treatment

The Mental Capacity Act (2005) allows adults over the age of 18 years to state, in writing, in advance what treatment they would not like carried out should they become unable to give consent. These decisions must be respected by all health care professionals, including nurses. The person must be deemed competent when making the advance directive, and only clear refusals of specific treatments will be upheld (surgery, drug therapy,

![Page 26: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/26.jpg)

Chapter 3: Legal and professional issues

49

etc). If any doubt exists, then treatment may be given ‘in the patient’s best interests’. Furthermore, a patient cannot refuse basic care, but if treatment falls within the remit of the Mental Health Act 1983, refusal cannot be over-ridden by an advanced directive (Peate, 2012).

Mental Health Acts

For people detained under relevant mental health legislation, the principles of consent continue to apply for all conditions not related to the mental disorder.

Further information about consent can be obtained from the Depart-ment of Health website at www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/138296/dh_103653__1_.pdf

Key guidance includes:

• reference guide to consent for examination or treatment;

• good practice in consent implementation guide.

In addition, on the same website, there is information about consent forms and associated guidance for patients. Another website with infor-mation about the Mental Capacity Act (2005) is the Department of Justice (www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/contents).

F U R T H E R i N F O R m AT i O N

ConfidentialityConfidentiality is a fundamental part of the patient / carer relationship. Any information given to a nurse by a patient should not be passed on to anyone outside the health care team without the patient’s consent. The fundamen-tal importance of trust between a health professional and the patient brings with it a ‘duty of confidence’ (Caulfield, 2005).

This duty arises from:

• duty of care in negligence (discussed earlier in the chapter) – a breach of confidentiality can lead to civil action;

• implied duties under the nurse’s contract of employment;

![Page 27: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/27.jpg)

A Handbook for Student Nurses

50

• requirements of the NMC outlined in The Code – a breach of this could result in removal from the nurses’ register.

The NMC endorses Caulfield’s statements in The Code by stating (NMC, 2015, Sections 5–7): ‘As a nurse or midwife you owe a duty of confidentiality to all those who are receiving care. This includes making sure they are informed about their care and that information about them is shared appropriately’.

Disclosing information

Although The Code requires you to respect patient confidentiality, it also states that you must:

• share information if you believe someone may be at risk of harm, in line with the laws relating to the disclosure of information.

(NMC, 2015, Section 17.2)

However, disclosure of confidential information without consent should only happen in exceptional circumstances. Nurses must be able to justify their actions in doing so, and it must only be done in the public interest to protect individuals, groups or society as a whole from the risk of significant harm. Examples could include child abuse, serious crime or drug trafficking. If a decision to disclose is made, a clear and accurate account should be recorded in the person’s records.

Dimond (2011) summarises this when stating there are seven exceptions to the duty of confidence, when nurses can divulge information about their patients:

• with the patient’s consent;

• in the patient’s best interests;

• by court order;

• under a statutory duty to disclose;

• in the public interests;

• to the police;

• under provisions within the Data Protection Act (1998).

Confidentiality does not only apply within a health care setting. As a stu-dent you may wish to refer to a real-life situation you have been involved with in an academic assignment. If so, your university will have guidelines on confidentiality that you must abide by, which will advise you not to pro-vide any information that could identify a particular patient.

![Page 28: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/28.jpg)

Chapter 3: Legal and professional issues

51

Ownership of and access to records

Records of information belong to an organisation (for example, a hospital) and not to specific people. People can, however, request to see their paper-held and computer-held notes, usually on payment of a fee, under the following Acts:

• The Data Protection Act 1998 gives the patient a statutory right to access personal information in the form of health records held on them (both computer and manually-held records). The definition of ‘health record’ includes all records relating to their health, such as nursing records, physiotherapy records, laboratory results, etc. The patient also has the right of rectification, that is, correcting or amending the data recorded, if they appear to be inaccurate.

• The Access to Medical Reports Act 1988 gives an individual the right of access to any medical report relating to them which is supplied for employment or insurance purposes.

• The Access to Health Records Act 1990 governs access to health records of deceased people.

• The Freedom of Information Act 2000 and Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 grant anyone the right to information held by public authorities that is not covered by the Data Protection Act 1998.

Caldicott Guardians

A review was commissioned in 1997 by the Chief Medical Officer of England in response to:

increasingconcernaboutthewaysinwhichpatientinformationisbeingused in the NHS in England andWales and the need to ensure thatconfidentialityisnotundermined.Suchconcernwaslargelyduetothedevelopmentofinformationtechnologyintheservice,anditscapacitytodisseminateinformationaboutpatientsrapidlyandextensively.

(DepartmentofHealth,1999)

As a result of the report every NHS organisation is required to appoint a ‘Caldicott Guardian’ who is responsible for agreeing and reviewing internal protocols governing the protection and use of patient-identifiable informa-tion by the staff of their organisations.

![Page 29: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/29.jpg)

A Handbook for Student Nurses

52

• Further information about confidentiality can be obtained from the Department of Health website at www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/200146/Confidentiality_-_NHS_Code_of_Practice.pdf.

• Key guidance includes:

• what is confidential information?;

• providing a confidential service;

• legal requirements;

• a list of confidentiality decisions.

F U R T H E R i N F O R m AT i O N

Record keepingRecord keeping is part of the professional duty of care owed by the regis-tered nurse to the patient. As a student you can take part in record keeping activities provided you have the knowledge and skills to undertake this and you are adequately supervised. Your ability to contribute to record keeping will be assessed in your practice area by the person delegating the task to you (usually your mentor) – if they feel you are not competent they must clearly countersign any entries made by you.

Record keeping is an integral part of nursing and midwifery practice. It is a tool of professional practice and one that should help the care process and it is not an optional extra to be fitted in if circumstances allow. Failure to maintain reasonable standards of record keeping could be evidence of professional misconduct and subject to professional conduct proceedings.

The NMC (2009b, p. 12) further states that good record keeping helps to protect the welfare of patients/clients by:

• helping to improve accountability;

• showing how decisions related to patient care were made;

• supporting the delivery of services;

• supporting effective clinical judgements and decisions;

![Page 30: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/30.jpg)

Chapter 3: Legal and professional issues

53

• supporting patient care and communications;

• making continuity of care easier;

• providing documentary evidence of services delivered;

• promoting better communication and sharing of information between members of the multi-professional health care team;

• helping to identify risks, and enabling early detection of complications;

• supporting clinical audit, research, allocation of resources and performance planning;

• helping to address complaints or legal processes.

Patients should be equal partners, whenever possible, in the completion of their records. They have the right to expect that all health care profession-als, including registered nurses and student nurses who contribute to their records, will practise a high standard of record keeping. Therefore, failure on the part of a registered nurse to maintain reasonable standards of record keeping could be evidence of professional misconduct and subject to Fit-ness to Practise proceedings. Records can also be called as evidence by the Health Services Commissioner, before a court of law, or in a local investi-gation of a complaint made by a patient. This may include anything that makes reference to a patient such as:

• handwritten clinical notes;

• emails;

• letters to and from other health professionals;

• laboratory reports;

• X-rays;

• printouts from monitoring equipment;

• incident reports and statements;

• photographs;

• videos;

• recordings of telephone conversations;

• text messages.

![Page 31: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/31.jpg)

A Handbook for Student Nurses

54

Any absence of a record may be seen as a lack of care, negligence, inabil-ity to write a record, lack of interest, concealment or a general failure to communicate in the best interest of the patient. A coroner stated: ‘Nurses are good observers - it’s only a question of whether or not they write their observations down – when they come to court to testify, facts which seemed trivial at the time take on a paramount importance’ (anon).

Content and style

The principles of good record keeping include:

• Handwriting should be legible.

• All entries to records should be signed. In the case of written records, the person’s name and job title should be printed alongside the first entry.

• In line with local policy, you should put the date and time on all records. This should be in real time and chronological order, and be as close to the actual time as possible.

• Records should be accurate and recorded in such a way that the meaning is clear.

• Records should be factual and not include unnecessary abbreviations, jargon, meaningless phrases or irrelevant speculation.

• Professional judgement should be used to decide what is relevant and what should be recorded.

• Include details of any assessments and reviews undertaken, and provide clear evidence of the arrangements you have made for future and ongoing care. This should also include details of information given about care and treatment.

• No alteration or destruction of any records without being authorised to do so.

• Alteration to your own or another healthcare professional's records must include your name and job title, and you should sign and date the original documentation. You should make sure that the alterations you make, and the original record, are clear and auditable.

• Where appropriate, the person in your care, or their carer, should be involved in the record keeping process.

![Page 32: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/32.jpg)

Chapter 3: Legal and professional issues

55

• Records should be readable when photocopied or scanned;

• You should not use coded expressions of sarcasm or humorous abbreviations to describe the people in your care.

Maintaining professional knowledge and competence (revalidation)Once you are a registered nurse you will have to undertake post-registration education and practice (Prep), although this is changing in December 2015 and will be called revalidation. Prep is a set of NMC professional standards and guidance designed to help nurses provide the best possible care for patients and keep up to date with developments in practice by thinking and reflecting on their practice (NMC, 2011).

Currently, in order to renew registration every year registered nurses must provide a signed Notification of Practice (NOP), which asks them, amongst other things, to declare that they have met the Prep requirements. There are two separate Prep standards which affect registration (NMC, 2011, p. 5):

• The Prep (practice) standard – nurses must have worked in some capacity by virtue of their nursing or midwifery qualification for a minimum of 450 hours during the previous three years, or have successfully undertaken an approved return to practice course within the last three years;

• The Prep (continuing professional development) standard – nurses must have undertaken and recorded their continuing professional development (CPD) over the three years prior to the renewal of their registration.

Continuing professional development is defined as:

A process of lifelong learning for all individuals which meets theneeds of patients and delivers health outcomes and health careprioritiesoftheNHSwhichenablesprofessionalstoexpandandfulfiltheirpotential.

(HSC,1999/194).

Although this definition specifically refers to the NHS, it applies to all areas where registered nurses are employed.

To satisfy the Prep CPD standard (NMC, 2011, p. 9) registered nurses must produce evidence that they:

![Page 33: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/33.jpg)

A Handbook for Student Nurses

56

• have undertaken at least 35 hours of learning activity relevant to their practice during the three years prior to renewal of registration;

• have maintained a personal professional profile (PPP) of their learning activity;

• comply with any request from the NMC to audit how these requirements have been met.

For further details on how to meet the Prep requirements see The Prep Handbook (2011) at www.nmc-uk.org.

Providing care in an emergency situation outside the work environment

The NMC (2015, p. 15) has added a section on offering help if an emergency arises in your practice setting or anywhere else. It states:

• only act in an emergency within the limits of your knowledge and competence (Section 15.1)

• arrange, wherever possible, for emergency care to be accessed and provided promptly (Section 15.2)

• take account of your own safety, the safety of others and the availability of other options for providing care (Section 15.3).

Giving assistance in an emergency or accident spans all the areas of account-ability nurses are concerned with (criminal, civil, employment and profes-sional law), and as a student you should be aware of the implications for you. In the UK there is generally no legal obligation to provide care or assis-tance in an emergency situation. However, in an emergency, in or outside the work setting, registered nurses have a professional duty to provide care, and in providing that care they are accountable for any actions or omissions in their practice, and would be judged against what could reasonably be expected from someone with their knowledge, skills and abilities in those circumstances. They would need to ensure that they work within the limits of their competence and that they are able to demonstrate that they acted in the person’s best interests.

The NMC also acknowledges that student nurses may be placed in emer-gency situations on occasion; their advice is the same as in The Code, i.e. that you only act within the limits of your knowledge and competence (NMC, 2015, Section 15.1).

![Page 34: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/34.jpg)

Chapter 3: Legal and professional issues

57

And finally…..

Listed below are some of the common reasons why registered nurses are removed from the NMC register. Removal from the register is a result of the findings of Fitness to Practise panels where registered nurses’ conduct and performance are measured against The Code (NMC, 2015). Anyone has the right to complain to the NMC about a registered nurse – fellow registered nurses, colleagues in other healthcare professions, patients and their fami-lies, employers, managers and the police. Grounds for removal in 2011–12 included:

• Prescribing/drug administration 12.5%

• Record keeping 11.5%

• Clinical treatment issues 10%

• Dishonesty 8%

• Neglect of patients 6%

• Patient care 5%

• Non-clinical incidents 5%

• Lack of knowledge, skills and judgement 3%

• Physical abuse 3%

• Verbal abuse 2.5%

• Drug- or drink-related offences 2%

• Communication issues 2%

• Theft 2%

• Violence towards colleagues 2%

• Management/delegation 2%

Perhaps not on such a serious scale as the above, if you as a student nurse have any doubts about the actions or performance of a registered nurse, you mustn’t ignore the situation even if it could put you in a difficult posi-tion. The NMC Code (NMC, 2015, Section 16.1) advises that you ‘raise and, if necessary, escalate any concerns you may have about patient or public safety, or the level of care people are receiving in your workplace or any

![Page 35: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/35.jpg)

A Handbook for Student Nurses

58

other healthcare setting and use the channels available to you in line with our guidance and your local working practices’. You should also discuss this with your university advisor.

VisittheNMCwebsiteatwww.nmc.org.uk/concerns-nurses-midwives/hearings-and-outcomes/schedule-and-outcomes/andfinddetailsofrecentFitnesstoPractisecases.LookatthefactsofthecasesandseehowtheNMCdecidedtodealwiththeallegations.

A C T i v i T y 3 . 3

This section has given a very brief introduction to the law. Further detail can be found in a variety of texts written for nurses, perhaps the most comprehensive being Bridgit Dimond’s Legal Aspects of Nursing, and Helen Caulfield’s Accountability (see reference list). The follow-ing websites are also useful:

Alzheimer’s Society www.alzheimers.org.uk (accessed 17 March 2015)

British Medical Council www.bma.org.uk

Department of Justice www.justice.gov.uk (Mental Capacity Act)

Department of Health www.dh.gov.uk

European Court of Human Rights www.echr.coe.int

General Medical Council www.gmc-uk.org

Health Service Ombudsman www.ombudsman.org.uk

Law Society for England and Wales (has a useful section on clinical negligence) www.lawsociety.org.uk

Nursing and Midwifery Council www.nmc-uk.org

Royal College of Nursing www.rcn.org.uk

F U R T H E R R E A d i N g

![Page 36: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/36.jpg)

Chapter 3: Legal and professional issues

59

Chapter summary• Registered nurses are accountable in the criminal courts, the civil

courts, before their employer and before the Fitness to Practise Committees of the NMC.

• Student nurses are similarly responsible to the criminal courts, civil courts, their university and placement provider and must act within The Code: Professional Standards of Practice and Behaviour for Nurses and Midwives (NMC, 2015).

• Department of Health and NMC guidance for gaining consent, ensuring confidentiality and record keeping must be adhered to.

• Nurses must engage in continuing professional development throughout their working lives.

ReferencesBanks, S. (2004) Ethics, Accountability and the Social Professions.

Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Castledine, G. (1991) Accountability in Delivering Care. Nursing Standard, 5 (25), 13: 28–30.

Caulfield, H. (2005) Vital Notes for Nurses: Accountability. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Department of Health (1999) Caldicott Guardians, NHS Executive, HSC, 1999/012. London: Department of Health.

Department of Health (2009) Reference Guide to Consent for Examination or Treatment (2nd edition). London: Department of Health.

Department of Health (2014) Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS). London: Department of Health.

Dimond, B. (2011) Legal Aspects of Nursing (6th edition). London: Pearson.

Health Act (1999) www.legislation.gov.uk (accessed 1 June 2015)

HSC (1999/194) Continuing Professional Development (Quality in the New NHS). London: Department of Health.

Mental Capacity Act (2005) www.legislation.gov.uk (accessed 1 June 2015)

![Page 37: 2015–16 EDITIONtext for student nurses, written in a clear and illuminative style.” “[An] excellent textbook that provides up-to-date and relevant information for pre- and post-registration](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022052002/601481a4b188c938a152c748/html5/thumbnails/37.jpg)

A Handbook for Student Nurses

60

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2010) Good Health and Good Character: Guidance for Approved Education Institutions. London: NMC.

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2011) The Prep Handbook. London: NMC.

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2014) Our Role. www.nmc-uk.org/About-us/Our-role/ (accessed 5 March 2015)

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2015) The Code: Professional Standards of Practice and Behaviour for Nurses and Midwives. London: NMC.

Nursing and Midwifery Order (2001) www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2002/253/contents/made (accessed 10 June 2015)

Peate, I. (2012) The Student’s Guide to Becoming a Nurse. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Richards, A. & Edwards, S. (2008) A Nurse’s Survival Guide to the Ward. London: Churchill Livingstone.

Tingle, J. & Cribb, A. (2007) Nursing Law and Ethics (3rd edition). Oxford: Blackwell.