OUT OF THE NORTH The Subarctic Collection of the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology

2014 Contexts--Annual Report of the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology

-

Upload

haffenreffer-museum-of-anthropology -

Category

Documents

-

view

204 -

download

0

description

Transcript of 2014 Contexts--Annual Report of the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology

-

CONTEXTSTheAnnual Report of the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology

Volume 39 Spring 2014

-

The Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology is Brown Universitysteaching museum. We inspire creative and critical thinking about cultureby fostering interdisciplinary understanding of the material world.

The museums gallery is in Manning Hall, 21 Prospect Street, Providence,Rhode Island, on Browns main green. The museums CollectionsResearch Center and Circumpolar Laboratory are at 300 Tower Street,Bristol, Rhode Island.

Manning Hall Gallery Hours:Tuesday Sunday, 10 a.m. 4 p.m.

Haffenreffer Museum of AnthropologyBox 1965Brown UniversityProvidence, RI 02912www.brown.edu/Haffenrefferwww.facebook.com/HaffenrefferMuseum(401) [email protected]

About the Museum

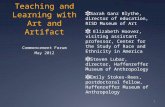

On the front cover (clockwise from upper left): Doing research on an Egyptian Old Kingdom carving; a pre-Columbian vessel from Costa Rica donatedto the Museum; students in Faculty Fellow Elizabeth Hoovers class Native American Environmental Health Movements examine an Inuit mukluk in CultureLab;a Thai Spirit House purchased for the collection; delegates of the Bangwa (Lebialem) community examine masks collected by Robert Brain in Cameroon.

-

1As the new Director of the HaffenrefferMuseum of Anthropology, I would liketo share some thoughts about museumsin general and university-basedanthropology museums in particular.

All museums, from the Smithsonian Institution,to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, to the HaffenrefferMuseum, are experiencing challenging times today.They are facing increasing public scrutiny regardingtheir traditionalmissions. There is an ongoing academicdiscourse about their elitist origins, their collectinghistories, and their representational authority. At thesame time, there is a popular debate about the valueof museums in the Internet age. After all, why goto a museum if you can see their collections on-line?

These challenges have led to a productive rethinkingof the functions of museums and a growing awarenessof the importance of engaging the needs and agendasof diverse interest groups. A newmuseum ethos isemerging that sees museums not as passive reposito-ries of things, but as places where new relationshipscan be established. The Internet has not renderedmuseums obsolete; rather, it has provided a new con-text for museums to reach out to broader audiences.Museums are now recognized as active participantsin society, often taking on challenging social issuesin order to highlight injustices and to promote greatercross-cultural understandings.

University-based anthropology museums, like theHaffenreffer Museum, occupy a special role in thisnew landscape. Such museums are places for theacquisition of new knowledge through archaeologicaland anthropological fieldwork and research. They areplaces for the development of innovative approachesto teaching. They are places for the exploration ofrepresentational practices by combining virtual anddigital exhibitions. They are places for the promotionof ethical practices regarding collecting, stewardship,and repatriation.

My vision is for the Haffenreffer Museum to helpshape this new ethos, both nationally and in the stateof Rhode Island. The Haffenreffer is well positionedto serve as a key site for the production of new under-standings about thematerial mediation of culture,in the past and for the present. It provides unparalleledopportunities for faculty and students to explore someof the interrelationships between identity discourseand heritage claims in all their complexities and nuances.Significantly, this new dialogue needs to criticallyexamine the interface between objects and their repre-sentations, museums and the Internet, and researchand teaching, for the benefit of multiple audiences.

Robert W. Preucel

From

theDire

ctor

-

2Haffenreffer Faculty FellowsProgram InstitutedThe Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology hasestablished a Faculty Fellows Program to encouragefaculty to use themuseums collections in theirteaching. The 2013-2014 fellows are Ariella Azoulay(Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature andModern Culture and Media), Peter van Dommelen(Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology),Paja Faudree (Assistant Professor of Anthropology)and Elizabeth Hoover (Assistant Professor ofAmerican Studies). Stephen Houston (Professorof Anthropology), and Andrew Scherer (AssistantProfessor of Anthropology) will share the award.More information on this project appears on page 7.

TwoPostdoctoralFellows are AppointedThe Museum has appointed two PostdoctoralFellows for the academic year. Jennifer Stampe hasbeen reappointed as the Postdoctoral Fellow inMuseum Studies. She is particularly interested inAmerican Indian self-representations in museumsand tourist sites and non-Native responses to theserepresentations. Sean Gantt has been appointedas the Postdoctoral Fellow in Native AmericanStudies. Sean is a visual and public anthropologistspecializing in tribal economic development,Indigenous self-representation, and identity amongSoutheastern tribes.

Mellon Foundationfunds collaborationwith RISDs ArtMuseumRobert Preucel and John Smith (Director of theRISD Art Museum) received a four-year $500,000grant from the AndrewW. Mellon Foundation tosupport a program on object based teaching andresearch. The organizing concept for the program isthe idea of the assemblage, which has a varietyof meanings in different disciplines. The project willinvolve Faculty Teaching Fellows, Postgrad/PostdocPhotography Fellows, conferences and workshops.It is the first major collaboration between ourtwomuseums.

NSF funds researchonwomens rolesin the production and tradeof cloth in theNorth AtlanticMichle Hayeur Smithwas awarded a three-year,$605,000 research grant from the National ScienceFoundations Arctic Social Sciences program toexamine womens roles in the production and tradeof cloth across the North Atlantic from the VikingAge into the early 1800s. Dr. Hayeur Smiths newproject expands upon her previous, successful,3-year (2010-2013) collections-based archaeologicalproject also funded by the Arctic Social Sciencesprogram. This is the largest federal research grantever received by the Haffenreffer Museum. Moreon Dr. Hayeur Smiths research can be found onpage 14.

NSF funds Viking Age researchKevin Smith received a $45,503 RAPID grant fromthe National Science Foundations Arctic SocialSciences program to conduct emergency excavationson a Viking Age site deep within Icelands Surtshellirlava cave. The work done in August 2013 resultedin the recovery of a unique and informative assem-blage of Viking Age objects and produced newradiocarbon dates. More information on this projectappears on page 15.

CollectionsManagement SystemsBeing RevampedWith support from the Office of the Provost,the Haffenreffer Museum is preparing to migrateits database system from Argus to ZetcomsMuseumPlus Collections Management System.The move to MuseumPlus will allow the museumtomanage the collections more efficiently andmake them available online to faculty, students, andthe public. More on thismigration can be found onpage 19.

Announ

cements

-

Our fall season kicked off with Christopher Steiner(Connecticut College) joining us as the Jane PowellDwyer Lecturer. In his talk, The Invention of AfricanArt, he discussed African art exhibitions and theirroles in encouraging new forms of reproduction,tourist art, and copies.

We sponsored a series of programs during BrownsFamily weekend that also fell on the ArchaeologicalInstitute of Americas International Archaeology Day.Our programs included a talk by director RobertPreucel, who discussed his research in NewPerspectives on the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. MuseumProctor Jen Thum, a graduate student in theJoukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the AncientWorld, demonstrated her work using RTI analysisto transcribe an Egyptian tomb relief in Digital Magicin Ancient Egypt. To cap off the day, MuseumCurator Thierry Gentis gave a curators tour ofThe Spirit of the Thing Given.

Praveena Gullapalli (Rhode Island College) engagedus with her presentation What Happens in aMuseum? Exhibits, Display Strategies and VisitorEngagements. Dr. Gullapalli discussed interactionsbetweenmuseums attempts to speak to audiencesthroughmuseum displays and visitors preconcep-tions that dont always interact with exhibits in waysexpected or designed by their curators.

In conjunction with the Love Medicine exhibit, wehosted a Roundtable Discussion of Louise ErdrichsLove Medicine in collaboration with the NativeHeritage Series at Brown and sponsored by theTomaquagMuseum.DawnDove, Narragansett elder,oral historian, author, and educator led the panel,

which includedDr.Maria Lawrence, Ramapaugh, andRhode Island College Professor of Education; LornSpears, Narragansett, Executive Director of theTomaquag Museum, educator, artist, and author;Dr. Elizabeth Hoover, Mohawk/Mikmaq, Professorof American Studies at Brown; and Paulla Jennings,Niantic/Narragansett, elder and oral historian.Panelists discussed key themes in Love Medicineand their relevance to their communities.

William Yellow Robe, Jr. (Assiniboine, Universityof Maine) discussed his work as a Native playwrightfor the Barbara Greenwald Memorial Arts Program.In a dynamic talk entitled Native American TribalTheatre, he spoke about the trials of establishinghimself as a Native author and working with variousNative communities to use theatre for individualand community healing.

PublicProgramsandEvents

Guests at Sergei Kan's lecture examine the Museums Chilkat blanketwith deputy director Kevin Smith (left) and director Robert Preucel(second from right).

Undergraduate and graduatestudents chat about researchwith Sergei Kan at one of theMuseums Pizza Roundtablediscussions for Brown Universitystudents and faculty.

Geralyn DucadyCurator for Programs and Education

Fall 2013

-

4Our spring programming started with events linkedto our new exhibit In Deo Speramus: The Symbolsand Ceremonies of Brown University and Browns250th Anniversary opening weekend. We hosted aprogram for middle school students spending a dayat Brown in which they had a chance to learn howto look at, analyze, and handle objects in CultureLab.We served cookies and cocoa during a late night,University-wide celebration open to the public. Thefollowingmorning,WilliamSimmons, Professor ofAnthropology, led a curators tour of the new exhibit.

In further celebration of Browns sesquicentennial,the HaffenrefferMuseum Student Group hosteda scavenger hunt of Brown Universitys Signs andSymbols for the Brown community, coordinated byStudent Groupmembers Abby Muller and LauraBerman, and we hosted a talk, Inventing Tradition,by Jane Lancaster (Brown University) on the originsof some of Browns traditions, the invention oftradition, and how traditions create community.

In Stealing the Past: Collectors and Museums ofthe 21st Century, RichardM. Leventhal (Universityof Pennsylvania) discussed controversial aspectsof museum and private collecting practices that leadto the looting of archaeological sites. He called formuseums to set up global systems for long-termloans rather than using covert methods to acquireobjects of international cultural heritage.

Sergei Kan (Dartmouth College) was 2014s ShepardKrech III Lecturer and spoke of An Old Art Form forNew Occasions: Tlingit Totem Poles at the Dawn ofthe NewMillennium. Dr. Kan sharedmany decadesof work with Tlingit families in Southeast Alaska,discussing howmodern carvers have re-interpretedthe traditional totem pole to honor communitymembers and as symbols of healing.

For the Barbara A. and Edward G. Hail Lecture,artistMateo Romero spoke about his work as acontemporary Pueblo painter whose work drawson family connections at Cochiti Pueblo and hisexperiences among the Rio Grande pueblos. Hiswife,Melissa Talachy, a ceramic artist, gave ademonstration and workshop for student membersof Native Americans at Brown.

This spring we also collaborated with studentvolunteers fromBrown Green Events. Youmay haveseen the volunteers at our receptions dutifullyhelping you sort your trash, recyclables, andcompost. We earned a Gold Event Certificate forthe In Deo Speramus exhibit opening receptionby diverting 99.6% of our waste from the landfilland a Silver Event Certificate for Stealing thePasts reception.

Mateo Romero shares insightson his work with the audienceattending the annual Barbara A.and Edward G. Hail Lecture.

Richard M. Leventhal (University of Pennsylvania)chats with Museum guests at a reception in Manning Hallfollowing his talk, Stealing the Past.

Spring 2014

-

We finished our fifth year of the Think Like anArchaeologist program in 2014, partnering with theJoukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the AncientWorld, the RISDMuseum of Art, Providence PublicSchools, and Nathan Bishop Middle School. Thisyear, we also worked with teachers at NathanaelGreene and Roger Williams Middle Schools. To date,we have worked with seven teachers/librarians andmore than 1,700 students, including nearly 475students this year. Think Like an Archaeologistincludes four classroom sessions and one off-sitefocal session at the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthro-pology and the RISDMuseum of Art that introducesixth grade social studies students to the processesof archaeology from recording a survey tounderstanding stratigraphy, recording, mapping, andinterpreting an excavation site, and analyzing itsartifacts. Faculty, staff, and graduate students fromBrown and RISD lead each hands-on session.

The program enhances the social studies curriculumby helping students understand how researcherslearn about the past and develop critical, integrativethinking skills. We encourage students to practicewriting, collaborative problem solving, group work,and public speaking, while introducing them to keyarchaeological concepts such as stratigraphy,mapping, and dating. Through these approaches,we help students learn to synthesize differentsources of interdisciplinary information, at different

scales, and provide opportunities for studentsto work with real archaeologists, anthropologists,and museum educators. Teacher partners helpensure that the lessons fulfill state and CommonCore standards.

Rachel Shipps and Molly Kerker, our educationinterns and students in Browns Public Humanitiesprogram, worked with me on this project duringthe academic year, along with our partners fromthe RISDmuseum and the Joukowsky Institute. Ourteams success was shared at The MassachusettsArchaeological Education Consortiums (MAECON)first workshop last summer and I presenteda team-authored paper, Museum Education andArchaeology: Using Objects and Methodology toTeach 21st-century Skills in Middle School at theSociety for American Archaeologys annual meetingthis April. The papers co-authors are MarianiLefas-Tetenes (RISD Museum), Sarah Sharpe(Joukowsky Institute), and Christopher Audette(Nathan Bishop Middle School).

Thinking Likean ArchaeologistGeralyn DucadyCurator for Programsand Education

Collaborations

inEd

ucation

Exhibiting Animalswith the Brown/Fox PointEarly Childhood Education Center

We are in our second full year of collabo-rations with the principal and teachersat the Brown/Fox Point Early ChildhoodEducation Center, Inc. Piloted in thespring of 2012 by Public Humanitiesstudent Alexandra Goodman with theCenters four-year-olds, the programhas expanded to include three-year-oldsas well. Throughout the year, educationintern Rachel Shipps and I visitedeach classroom three to four times,the four-year-olds have come to the

museum twice, while the three-year-olds are gearing up for their first visitthis spring. Students learn about objecthandling, how to describe objects, andpropermuseum behavior. For the secondyear, the four-year-olds are workingwith the Museums staff to put togetheran exhibit with carefully selected objectsfrom the Haffenreffers collections.This years exhibit, Animal Faces andFigures will be installed in ProvidencesRochambeau Library.

-

Jennifer StampePostdoctoral FellowinMuseumAnthropologyI am a cultural anthropologist in my second yearas a Postdoctoral Fellow in Museum Anthropologyat Brown and the Haffenreffer. I have previouslytaught Museum Studies at New York Universityand Anthropology at the University of Minnesota,where I earnedmy PhD.

My teaching and research interests center on thecultural politics of indigeneity, focusing on NativeAmerican self-representation and sovereignty. Ihave conducted ethnographic fieldwork in residenceat the Mille Lacs Ojibwe Reservation in Minnesota.Focusing on theMille Lacs IndianMuseumandTradingPost State Historic Site, I examine the priorities andexperiences of Indigenous peoples in representingthemselves as well as the responses of non-Nativepeople to new, unexpected, representations. I havepublished articles from this research in the journalsTourist Studies and Settler Colonial Studies, andamworking on a book tentatively entitled YouWillLearn about Our Past: Representing Ojibwe Culturein the Treaty Rights Era.

At the Haffenreffer, I coordinate our new FacultyFellows Program and teach Anthropology in/of theMuseum [ANTH1901], a course that develops ananthropological approach to anthropologymuseums,understanding them as social spheres in their ownright. The course introduces students to object,visitor, and archival research in museums, usingthe Haffenreffers collections and facilities. Last fall,I curated an exhibit of Ojibwe and otherWoodlandsIndianmaterial to support the 2013-2014 Big Readin Rhode Island sponsored by the TomaquagMuseum. Most recently, I assisted Bill Simmonswith his work on In Deo Speramus: The Symbolsand Ceremonies of Brown University.

SeanGanttPostdoctoral Fellowin Native American StudiesI joined the Haffenreffer Museum this year as theMuseums Postdoctoral Fellow in Native AmericanStudies. In the course of the year I have strengthenedmy engagement with national and internationalNative American and Indigenous scholarship byactively participating and presenting my researchthrough theNative American and Indigenous StudiesAssociation (NAISA), the Society for AppliedAnthropology (SfAA), and Association of IndigenousAnthropologists (AIA) section within the AmericanAnthropological Association (AAA). I taughtIntroduction to American Indian Studies (ETHN1890),a cross-listed course in Ethnic Studies and Anthro-pology during the spring semester. I have also beenactively involved in developing the Native Americanand Indigenous Studies at Brown (NAISAB) interdis-ciplinary working group by helping to put on itslecture series, organize the Spring Thaw Powwow,and present my research at Brown and RogerWilliams University.

I am expandingmy involvement in academia whilemaintainingmy relationships in Mississippi and withNative American students and faculty at both theUniversity of NewMexico and Brown University. I amstrongly invested in working with undergraduateNative American students and student organizations,and have been mentoring and advising studentmembers of Native Americans at Brown (NAB).Much of my focus this past year has been workingwith students and organizations interested in NativeAmerican/Indigenous Studies here at BrownUniversity and serving as a liaison between thesegroups and programs, the Anthropology Department,and the Haffenreffer Museum. I have also partici-pated in the Haffenreffers events and contributedto the In Deo Speramus: The Symbols andCeremonies of Brown University exhibit throughdigital video editing.

6

PostdoctoralFellows

-

7Faculty

Fellows

This year the Haffenreffer Museum inaugurated aFaculty Fellows Program to encourage tenure-trackfaculty at Brown University to develop courses orcourse components using themuseums collectionsand facilities. The program formalizes and expandsthe Haffenreffers longstanding commitment toworking with faculty and others interested in teachingwith museum objects by granting a stipend tosupport Fellows research and course development.At the same time, it promotes object-based teachingacross the University by reaching out to facultywhomay not yet have thought of usingmuseumcollections in their teaching.

This year, after an open campus-wide call forproposals, we selected six facultymembers: ElizabethHoover from American Studies; Paja Faudree,Stephen Houston, and Andrew Scherer from Anthro-pology; Ariella Azoulay fromModern Culture andMedia; and Peter van Dommelen from Anthropologyand the Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology andthe Ancient World. They used objects and imagesfrom our collections to teach about issues as diverseas human-environment interactions, the wayslanguage andmaterial culture operate as complexsymbol systems, methods in anthropologicalarchaeology, the material quality of colonial andimperial relations, and the circulation of imagesand idioms of revolution and reform.

Over the year, Haffenreffer staff members introducedFellows to themuseums resources and assistedthem in identifying appropriate objects from thecollection, finding useful researchmaterials, anddeveloping object-based pedagogies. Course projectsincluded sessions in CultureLab and classroomsaround campus examining objects and archives,assignments from research papers to exhibitproposals, and innovative student projects including,in one case, making a reproduction of a headhuntersaxe in the Haffenreffers collection in order to under-stand howmaterials inspire human innovation.

The Faculty Fellows found the use of museumobjects to be extremely helpful in their educationalobjectives. Peter van Dommelen stated that Withoutthe rich variety of the Haffenreffers collections,my freshman seminar (Postcolonial Matters: MaterialCulture between Colonialism and Globalization -ANTH0066) would have beenmuchmore abstract.

That would have been a shame. Studyingmaterialculture is by nature hands-on: having real objectsat hand is crucial. Paja Faudree explained that,The Faculty Fellows Programmade an enormousdifference to me andmy students this term. Ithelpedmemake clear to the students, using newmaterials and new approaches, some of the funda-

mental insights of the course (Sounds and Symbols- ANTH0800). First, that thewayswe talk about things,and the ways we use language, have numerousmaterial effects andmanifestations. And second,that anthropologys central ideas about languagecan easily be applied to other semiotic systems,including those embedded in material objects. Inshort, the Faculty Fellows Program helpedmetransform the course and push it in rewarding andinnovative directions.

We encourage faculty from all disciplines toconsider adding amaterial culture component totheir teaching. Contact the museum to learnmore.

Students examine African objects of communicationfrom the Museums collections with curator Thierry Gentis (left)and Paja Faudree (right) in her class, Sounds and Symbols.

TheHaffenrefferMuseumWelcomesits First Faculty FellowsJennifer StampePostdoctoral Fellow in Museum Studies

-

The Haffenreffer Museums two Black Forest bears,recalling Brown Universitys mascot, stand beforethe universitys iconic VanWickle Gates at the entranceto In Deo Speramus: The Symbols and Ceremoniesof Brown University.

Symbolizing Brown:In Deo SperamusKicks OffBrownUniversitys SesquicentennialWilliam SimmonsProfessor of Anthropology

Symbols underpin all human socialand cultural life. They can be objects,words, or social practices that communi-cate sharedmeanings and ideas. Theycreate a sense of solidarity and inspireidentification with something beyondthe self, distinguish groups from oneanother, and orient action. They encodeprecedents and principles that serveas guidelines for initiating, resisting,and incorporating change.

While symbols may seem to be stable and eternalexpressions of enduring truths, they are surprisinglydynamic and easily adapted to newmeanings anduses. Brown Universitys symbols and ceremonieshave changed since its founding 250 years ago, yetthey provide a unifying sense of purpose, enshrininga version of the Universitys past that burnisheseven its newest traditions and serves to guides usin imagining the future.

On the occasion of the Universitys 250th anniversary,we assembled Browns central symbols for ourexhibit In Deo Speramus: The Symbols and Cere-monies of Brown, which opened in Manning Hallon Friday, March 7, 2014 as the first public eventin Browns 250th Anniversary celebration. In thisexhibit, we integrated objects, images, and actionsthat illustrate three dimensions of Brown Universityssymbolic life thematerial icons of Browns longhistory, Browns unique sense of place, and therejuvenating purpose of its academic processions.

Browns key symbol the design on the Corporationsseal has been through three transformations asthe university, itself, evolved. The first, of 1764, borethe profiles of Englands King George III and QueenCharlotte of England and was replaced after theAmerican Revolution with one that depicted a templeof learning inscribed with the names of the sevenliberal arts. Todays In Deo Speramus seal with itsradiant sun replaced the second when the Collegeof Rhode Island and Providence Plantations changedits name to Brown University. Other key symbols

Brown Universitys president, Christina Paxson,opens In Deo Speramus, on March 5, 2014,for Browns 250th anniversary.

Exhibitions

-

include logos and coats of arms, our bear mascot,the AlmaMater, the Presidents and Chancellorschains of office and academic gowns, and Brownsceremonial mace. All of these are assembled inIn Deo Speramus, with the Haffenreffer Museumshand carved Black Forest bears welcomingvisitors to the exhibit.

Colleges and universities, through their architectureand their placements, are among themost symbolicsites in our culture. Browns founders selectedfor its location an eight-acre tract that already hadstrong communal, theological, and ethical meaningsthat seeped into the college they planted and thatexists today. Throughmaps, interactive displays, anda student-generated scavenger hunt for Brownssymbols, we examine some of the continuities of pastand present that give meaning to Browns location.

Browns most symbolic gatherings are occasions onwhich the universitys dispersed community gathersto renew friendships, display its symbols, and, atcommencement, invest graduates with their personal

imprint of the seal on their diplomas. Through filmfootage, maps, and audio components we encouragevisitors to consider how singing the almamater,performing in contemporary a cappella groups, andmarching in a traditional order strengthens andrenews Brown itself through bonds forged betweensymbols, place, and the living community.

Jennifer Stampe, Postdoctoral Fellow in MuseumStudies, provided extraordinary guidance to the projectfrom the beginning. She and Nathan Arndt, HMAAssistant Curator, transformed the academic planinto an exhibit true to the tone that I hoped it couldconvey. Our undergraduate research apprentice,Emma Funk, was truly a gift to the project. JenniferBetts, University Archivist, went the extra mile timeafter time, as did her staff. Kirsten Hammerstromand J.D. Kay generously helped with materials fromthe Rhode Island Historical Societys collections, asdid KateWells and Jordan Goffin with the ProvidencePublic Library. Martha and ArtemisJoukowsky, Catherine Pincince,Rob Emlen, Mitchell Sibley,Tobias Lederberg, Russell Carey,Janet Cooper-Nelson, Mike Cohea,Steve Maiorisi, Jo-Ann Conklin,Michael Thorp, and Amalia Davisall contributed valuable expertise.

Clockwise, from top: Brown Universityspresidential gown and chain of office;the top of Brown's ceremonial mace;and the auditory artifacts cornerof In Deo Speramus, where sounds fromBrown's ceremonies, past and present,can be enjoyed.

-

Teaching with the Museum, a new exhibit in oursatellite space at the Stephen Roberts 62 CampusCenter showcases the Haffenreffer Museums newFaculty Fellows program and our commitment toobject-based teaching. It also aims to inspire facultymembers and others to consider usingmuseumobjects in their teaching.

There is an increasing appreciation in the academyfor the power and efficacy of object-based teaching.Teaching with objects makes abstract conceptsmaterial in ways that engage the senses. It provideshands-on experience and a form of knowledge that

students might not otherwise acquire. Objects alsoinspire discussion, teamwork, and lateral thinking,all of which are essential skills in higher educationand in the workplace.

The objects on display were used this year by Brownfaculty in their teaching. They includemukluks onceowned by Inupiat dancer and author Aknik (Paul)Green of Kotzebue Sound, Alaska. Elizabeth Hooverused these in her course Native AmericanEnvironmental Health Movements to emphasize theinventiveness of indigenous peoples in relationshipto their environment, and the threat environmental

I curated a special exhibit Reading Love Medicine:Beads, Bark, and Books from Ojibwe Country

in connection with the 2013-2014 BigRead program in Rhode Island,a year-long series of eventshosted by the TomaquagIndian Memorial Museum.The program selected LouiseErdrichs novel, LoveMedicine, a story of severalgenerations in two Ojibwefamilies set in a fictionalNorth Dakota community.We installed Reading LoveMedicine in a new locationfor us, the Finn Room ofBrown Universitys John D.Rockefeller, Jr. Library,where it was on display fromSeptember 27 throughOctober 24, 2013.

Our exhibit juxtaposed objects, such as beadedbandolier bags and birchbark baskets from Ojibwecountry, the Upper Great Lakes region of the USand Canada, with relevant books, many authoredby Native American scholars. Ojibwe people (alsoknown as Chippewa and Anishinaabe) have longshared this territory with other American Indiangroups, including the Dakota, Ho-Chunk, and

Potawatomi, and with Euro-American immigrants.The exhibit included objects that addressed thismulti-ethnic landscape. In keeping with the themesof Love Medicine, it examined stories that can betold by following the ways people have used things as gifts, commodities, andmementoes to forgeconnections across generations of Ojibwe people,among tribes in the Woodland regions of NorthAmerica, and between American Indian and non-Indian communities.

With its focus on books and stories, the exhibitprovided an opportunity to collaborate not only withthe Tomaquag Museum but also with BrownsRockefeller Library, whose Finn Room display spacegave us a forum for addressing a new audience.The library contributed to the exhibit by displayingbooks on Ojibwe culture and history fromits collection, and highlighting those by NativeAmerican scholars.

The Big Read is a program of the NationalEndowment for the Arts in partnership with the ArtsMidwest. The 2013-2014 Big Read in Rhode Islandwas hosted by the Tomaquag Indian MemorialMuseum, the states only Native-operated museum,with support from Brown Universitys HaffenrefferMuseum of Anthropology, its Third World Center,Native American and Indigenous Studies at Brown(NAISAB), and Native Americans at Brown (NAB).

Cap-tion

Reading LoveMedicine: Beads, Bark,andBooks fromOjibwe CountryJennifer StampePost-Doctoral Fellow in Museum Studies

Teachingwith theMuseum

10

continued on page 11

-

11

Exhibiting A Living Collection: Imagesof Power and ConnectionLaura Berman (Brown 14) andKevin P. Smith, Deputy Director/Chief Curator

Images of Power: Rulership in the Grasslands ofCameroon opened in themuseums Manning Hallgallery on November 15, 2013. The HaffenreffersStudent Group curated this exhibition under theleadership of Laura Berman (Brown 14), with objectsdrawn from themuseums vast African collections.Images of Power examines ways in whichCameroonian Grasslands kings, or fons, have usedimages and symbols of power drawn from indige-nous concepts of authority to legitimize their officesand their rights to rule despite, and at times inassociation with, potentially disrupting forces ofglobalization and colonialism. By choosing objectsfor this exhibition that were produced over thecourse of the late 19th through early 21st century,the exhibition challenges the notion of a dividebetween the traditional and the contemporary,querying instead the role of tradition within thepolitics of contemporary life.

The theme of the exhibit solidified after conversa-tions with a delegation of nobles and leaders fromCameroons Bangwa (Lebialem) community inAmerica. The delegation visited the Haffenreffer inthe summer of 2013 to see themuseums collectionof Bangwamasks collected by Robert Brain, ananthropologist who worked in the Bangwa capital ofFumban during the late 1960s. Mbe Tazi, the leaderof this group, remembered Brains visits from thetime he was a child and recognized several of themasks in themuseums collection as pieces carvedby his father. Their visit gave the group a newperspective on the enduring political and personalsignificance of these objects in Cameroonian society.Through these conversations and their research,the student groups exhibition also brings togethercontemporary and traditional museum perspectiveson the voices that inform visitors understandingof a living collection.

Teaching, continued from page 10

contamination poses to the health of individuals,communities, and places. For Peter van Dommelensfreshman seminar Postcolonial Matters, studentSamHill-Cristol, wrote a proposal for an exhibitcomparing Moro, Japanese, and Filipino weapons,understood as tools of colonial domination,appropriation, and resistance. Part of his proposal

Teaching, continued from page 10

appears as an exhibit-within-this-exhibit. An Ogonispirit mask fromNigeria and a Baule linguists stafffinial from Ghana, which illustrate subtle intercon-nections between abstract language andmoretangible material culture, were among the objectsthat students studied during Paja Faudrees courseSounds and Symbols.

-

12

Collaborating with the Haffenreffer Museumcontributed significantly to the success of BrownUniversitys first Mellon Sawyer Seminar, AnimalMagnetism: The Emotional Ecology of Animalsand Humans, and tomy teaching at Brown.

For Animal Magnetism, an interdisciplinary projectorganized by Browns Program in Early Cultures,I curated, with anthropology graduate student Alycede Cartaret, two displays using objects from theHaffenreffers collections to engage the themeof human/animal interactions. Our first installationcontrasted archaeological objects frompre-ColumbianPeru, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic thatrepresented non-human animals more-or-lessrepresentationally although with less directlyrepresentational meanings with others, ethno-graphic and archaeological, made expressly fromanimal parts. This exhibition contributed to ourworkshop, Menageries and the Giving and CostlyPet. Our Graduate Fellows, Alyce de Carteret,Michiel vanVeldhuizen, andClive Vella eachdiscussedan object from the exhibit during one of the work-

shops receptions, exposing our guests to thecollection and adding a valuablematerial cultureelement to our seminar.

This, and our second installation, which focused onthe theme of hybridity, also contributed significantlytomy teaching at Brown. I assigned each of thestudents in my class, Animals in the Ancient City:Interdependence in the Urban Environment, to look,study, and describe their experience of understandingone object from the first exhibit. Then, they wereasked to examine the second exhibit and brainstormthe significance of the hybrid features of each objectand speculate on its meaning in its culture of origin.

During our most recent workshop, The Pushmi-Pullyu of Consocial Life, the Animal Magnetismseminar benefited from yet another collaboration:that between the Haffenreffer and Public HumanitiesJenks Society for Lost Museums. The Jenks Societygave a very well received presentation at ouropening reception and, so, we benefited yet againfromHaffenreffer collaborations!

Mutual Attractions:AnimalMagnetism andMuseumCollectionsSusan CurryPostdoctoral Fellow, Joukowsky Institutefor Archaeology and the Ancient World

As Assistant Curator at the Haffenreffer Museum,I have been looking for ways to introduce newtechnologies and digital media into our exhibitsnot only to give patrons improved experiences,but also to maintain secure and stable conditionsfor our collections.

This year I worked with a number of groups withinBrown to expand our use of digital technologies.Our goal was to enhance the objects on display byproviding access to a larger selection of objectsthrough digital media. The introduction of BrownsTouch Art Gallery (TAG) database into the In DeoSperamus exhibit was a key element in making thispossible. We added hundreds of photographsand additional details into a database that can be

searched by those interacting with the exhibit.As wemove into phase two of the exhibit, we planonmaking this program available online.

We also partnered with Ken DeBlois at CIS to designa customwebsite that would later become a digitalradio dial allowing an auditory history to be includedin the In Deo Speramus exhibit. While we haveincluded soundscapes before, this was the first timethat we have givenmuseum visitors the chanceto customize their experience.

Not all of the innovationsmade at themuseumwerevisible to visitors, but they all played an importantrole in moving us into the future. The use of LED

NewTricksNathan Arndt, Assistant Curator

New Tricks, contined on p. 16

Hybrid devilsmaskby the artist Juan Horta,of Michoacan, Mexico.

-

In 1680 the Pueblo Indian people of NewMexico andArizona successfully asserted their sovereignty inthe famous Pueblo Revolt and lived free of Spanishrule for 12 years. The period immediately followingthe revolt, however, was an especially turbulent timein the northern Rio Grande region. It was character-ized by multiple population movements involvingindividuals, families, clans, and even whole villagesin response to the anticipated return of the Spaniards.This high degree of mobility was facilitated byan intricate social network grounded in kinshiprelations and political alliances.

One of the most distinctive features of this periodis the shift in settlements frommission puebloslocated along the Rio Grande tomesa villages locatedon high, defensible promontories. In the Keres,Jemez, and Tewa districts, about ten newmesavillages were established (Table 1). Many of theseweremulti-ethnic, composed of groups of peoplefrom several different mission pueblos. Most wereinhabited during Diego de Vargass peaceablereconquest in 1692 and they posed a real threatto his authority. In 1694, Vargas mounted amajorcampaign against them and with the helpof his Indian allies successfully subdued them,one by one.

Since 1995, I have been working with Cochiti Puebloto research theirmesatop village known asHanatKotyiti (Cochiti above) located in the Santa FeNationalForest. The central goals of our project are to iden-tify the social processes surrounding the founding

and occupation of HanatKoytiti and to understand themeaning and significance ofthe village andmesa to theCochiti people today. Theproject involved archaeologi-cal survey andmapping,an oral history project, andan internship programmefor Cochiti youth.

My colleagues, MatthewLiebmann (AssociateProfessorat Harvard) and JosephAguilar (from San IldefonsoPueblo and a doctoralcandidate at the Universityof Pennsylvania), have

extended this research into the Jemez and Tewadistricts. Our research is revealing new insightsinto the cultural revitalization ideology of the PostRevolt period. For example, Popay, one of the keyleaders of the revolt, instructed his followers thatif they would live in accordance with the laws oftheir ancestors, they would have a bountiful harvestand could erect their houses and enjoy abundanthealth and leisure. This cultural revitalization discoursewasmadematerial in the architectural layout ofsome of themesa villages.

We have discovered that threemesa villages- HanatKotyiti, Patokwa, and Boletsakwa- were constructedas double plaza pueblos. This architectural formreproduces the communitys dual division socialstructure that, among the Keres and Jemez people,is expressed by the Turquoise and the Pumpkinmoieties. The villages may have even been built inthe image of the ancestral village known asWhiteHouse, the first village that people inhabited afterthey emerged from the underworld.

We are currently attempting to identify the flowsof people that circulated between some of thesemesatop villages and themission pueblos by meansof social network analysis. Our analysis is madepossible because of the Vargas journals that recordthemovements of the Pueblo people and evenmention some individuals by name. It is also facili-tated by means of the ceramics that Pueblo womenproduced, used, and discarded at these villages.Here historical archaeology can provide valuablenew insights into this poorly understood period.

13

Post Revolt Mesa Villagesof theNorthern Rio GrandeRobertW. Preucel,Director and Professor of Anthropology

Table 1.Post Revolt Mesa Villagesof the Rio Grande Region

Hanat Kotyiti Keres District

Canjilon Keres District

Old San Felipe Keres District

Patokwa Jemez District

Astialakwa Jemez District

Boletsakwa Jemez District

Cerro Colorado Jemez District

Tunyo Tewa District

Embudo Tewa District

San Juan Mesa Tewa District

Research

-

Weaving Islands:Archaeological Textiles and Genderin theNorth Atlantic, AD 800-1800Michle Hayeur SmithMuseumResearch Associate

In July 2013, I received a three-year, $605,000,research grant from theNational Science FoundationsArctic Social Sciences program to initiate a projectentitled Weaving Islands of Cloth: Gender, Textiles,and Trade Across the North Atlantic from the VikingAge to the Early Modern Period. This archaeological,collections-based project will expand on the scopeof my previous NSF-funded, 3-year (2010-2013)project, Rags to Riches An Archaeological Studyof Textiles and Gender in Iceland AD 874 -1800,andmy previous archaeological research on gender,dress, and adornment in medieval Iceland.

In Rags to Riches, I analyzed archaeological textileassemblages from 31 Icelandic archaeological sitesthat spanned 1,000 years andwas able to generatenew information on the roles ofmen andwomenin Icelandic society, changing approaches to textileproduction through time, the role of Icelandic textilesand women in international trade and Icelandseconomy, creative approaches that Icelands womendeveloped as sustainable responses to climate changeduring the Little Ice Age, and changes through timein Icelandic dress. Critically, I foundmaterial evidencein the form of increasingly standardized textileproduction that women were pivotal in makingIcelands cloth currency during themedieval period.Further, I was able to use these funds to obtainradiocarbon dates on textile samples frommostof these sites, enablingme to directly date critical

changes in textile production strategies andprovidemuch needed dating formany of the sitesI investigated.

Weaving Islands of Cloth will allowme to take theknowledge I gained and the lessons I learned fromRags to Riches to the next logical level: a comparative,millennium-scale examination of textiles as evidencefor womens labor and roles in all of the colonies thatNorse settlers established across the North Atlanticin the 9th century AD and that developed, over thefollowing centuries, into themodern nations ofScotland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland.This international collaborative project will integratecomparative analyses of existing collections in sixnationalmuseumswith a pilot project to assess thepotential for using isotopic and trace element analysestomonitor how clothmoved in trade across thisregion. Through these analyses, I hope to gain newinsights into the ways these island nations developed,while exploring womens roles in creating thefoundations of international trade, developing nationalidentities through the transformation of cloth intoclothing, and adapting to climate change.

Both of these grants are providing new insights intoNorth Atlantic archaeology andwomens roles in thedevelopment of northern societies and economies.They are also expanding the range of the HaffenrefferMuseums international partnerships and collabora-tions, with work underway inmuseums in, andwithcolleagues from, Iceland, Norway, Denmark, Sweden,Germany, Scotland, the Faroes Islands, Greenland,and Canada.

Icelands North Atlantic landscapes providedperfect grazing for the sheep whose wool forms the basisof Michle Hayeur Smiths current research.14

-

15

In August 2013, I received funding from the NationalScience Foundations Arctic Social Sciences Programto excavate an endangered Viking Age site deepinside western Icelands Surtshellir Cave. Surtshellir(Surts Cave) formed inside lava that flowed at thestart of the 10th century over six newly settled VikingAge farms, filled two upland valleys and covered242 km2 of grazing land.

For settlers just arriving from Scandinavia and theBritish Isles, this first experience of volcanic activitymust have been terrifying. They named this largestcave within the newly formed lava field for Surt, theelemental being they believed was present at theworlds creation and would eventually bring about itsdestruction and the gods death. Over succeedingcenturies, Surtshellir became associated with storiesabout chieftains seeking to placate Surt, outlawsravaging the surrounding region, acts of crueltymetedout by chieftains on their rivals, ghosts and evil spirits.Surtshellir may well have been themost dreadedplace in Iceland; but in 1750 two Icelandic naturalistsentered Surtshellir, dispelling these beliefs,describing a roofless house and piles of bones deepwithin the cave they believed was an outlawbands lair.

In 2001, colleagues from the National Museum ofIceland and I documented this enclosure, its bonepile, and amassive stone wall sealing the cave forthe first time, dating them to Icelands Viking Age(ca. 870-1000 AD). In 2012, we returned with

Mehrdad Kiani (Brown 15) to document thoseremains in greater detail. In doing so, we discoveredthat the enclosures delicate floor deposits, longassumed to be sterile, contained Viking Age artifactsthat were being actively damaged by touristsexploring the cave.

Last summer, we excavated these floor deposits andrecovered an unexpectedly informative suite of VikingAge artifacts that includes calibrated lead weights forweighing silver, a large assemblage of glass beadsincluding several that were probably produced in theMiddle East, and fragments of orpiment an arsenicore from theMediterranean used as pigment, poison,andmedicine. All of these arematerials associatedwith Viking Age chieftains rather than outlaws.In addition, scores of jasper and flint fire-starterfragments and 3-5 new areas where fragmentedbones of domestic animals had been piled orcremated document intense, focused activitiesundertaken over the course of a century in the totaldarkness of this caves interior. However, we foundno areas with residues from occupation, underminingthe outlaw occupation hypothesis. My colleaguesand I are nowworking on this material to unravelSurtshellirs subterranean secrets. Although wehave much to do, we now suspect that Surtshellirwas a sacrificial site where offerings weremade,quite possibly by Icelands Viking Age elites to placateSurtur and forestall the end of the world.

Deputy director Kevin Smith standsinside the Viking Age structure withinSurtshellir Cave.

Below: four lead scale weightsfrom the floor of the cave.Photograph by var Brynjlfsson,National Museum of Iceland.

Documenting a Den of Thievesor the Temple of Doom?Kevin P. SmithDeputy Director and Chief Curator

-

16

In early 2011, I received funds from the NationalScience Foundations Arctic Social Sciences programto investigate the origins of northern Alaskas enig-matic Old Whaling Culture, first documented in 1958by William Simmons (then a Brown undergraduate,now Professor of Anthropology) and J. Louis Giddings(the Haffenreffer Museums first director). OldWhaling, perhaps the earliest arctic whale huntingculture, is still known in Alaska from a single site Giddings and Simmons initial discovery on CapeKrusenstern and on the Siberian side by two possiblyrelated sites. Since its discovery, the Old Whalingsite and the origins of its occupants have beenscrutinized several times with ambiguous results.It has been suggested, for example, both that theOld Whalers came to Cape Krusenstern fromSiberia or that they were Indians from Alaskasinterior; that the Old Whaling site was a short termencampment or that it has underlying layerssuggesting a longer occupation or the presence ofearlier residents; and that its different house typesrepresent summer and winter villages of a singlegroup or different occupations entirely.

My field research at the Old Whaling site soughtto investigate whether earlier occupations did existthere and to assess whether they could indicatehistorical connections between the Old Whalersand other documented cultures in the Bering StraitRegion. To that end, we returned, with NSF funding,to assess the sites stratigraphy through geophysicalsurveys and test excavations. While that investigationdid not reveal evidence of preceding occupations,we learned a great deal about the sites taphonomyand the effects of contemporary climate changein the region and on its archaeological resources.

In 2013, we pooled the remaining NSF funds withmoney contributed from the Haffenreffer Museum

and fromMichele Hayeur Smiths Rags to Richesgrant to purchase a Bruker Tracer III-SX portableX-ray fluorescence device that we are now using toanalyze the lithic assemblage from the site so thatwe can assess and compare stone tool use andcuration across cultures. In particular, we are lookingfor any similarities in rawmaterial procurementand production strategies between the Old Whalersand near-contemporaneous cultures in the regionthat could help us to assess possible historicalrelationships and provide clues to the Old WhalingCultures origins. This ongoing research has providedtraining and employment for Brown University andPlattsburgh State University undergraduate students.Further studies will include both microscopic andmacroscopic analyses of the various artifacts fromthe site curated at the Circumpolar Laboratory ofthe Haffenreffer Museum.

Seeking the Originsof the OldWhaling CultureChristopherWolffMuseumResearch Associate/Assistant Professorof Anthropology, SUNY-Plattsburgh

technology has given themuseum greater lightcontrol while minimizing the risk of UV damage toour collections. This technology has been in usein the past, but we have recently begun an initiativeto change our exhibit and work spaces to these lightsources to provide better care for our collections.

While these changes seem small, they allow usto bring the collections to a wider audience and willcreate safer exhibits with the ability change regularly,giving our visitors a new and shared experienceevery time they walk through our doors.

New Tricks, contined from p. 12

-

17

Seeking OldWhalersConnor Hilton (Brown 15), Student Research Assistant

AnOld KingdomEgyptian ReliefRevealed throughRTI:Jennifer ThumHaffenreffer/Joukowsky Institute Proctor

X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) can be a powerful toolfor measuring the elemental profiles of geological,archaeological, and ethnographic objects. At theHaffenreffer Museum, I am currently assisting KevinSmith and Chris Wolff in analyzing scrapers, projec-tile points, and knives from the Old Whaling Site inAlaska, using the Museums newly acquired portableXRF set-up. While many chert or chalcedony objectslook similar, XRF analysis allows us to differentiatethem at the elemental level. We are seeking linkagesbetween objects from different parts of Old WhalingSite, comparisons with the types of stone that earlierand later occupants of Cape Krusenstern usedfor making tools, and similarities with rawmaterialfrom known sources of chert, chalcedony, and obsid-ian in Alaska. This will hopefully provide insights intothemobility and origins of the Old Whalers and

their knowledge of the regions resources. Commonmarkers that we see include Barium, Strontium,Zirconium, and Yttrium, which are not present in allof the tools or in the same ratios. Comparing thepresence and relative intensities of elements suchas these will hopefully result in distinct groupingsof rawmaterial and, from these, insights into thecommunities that used them.

I am a doctoral candidate studying Egyptology in theArchaeology and Ancient World Program at theJoukowsky Institute. This fall I held a proctorship atthe Haffenreffer Museum, and tomy surprise foundthat themuseum had in its collection a raised-relieflimestone block from the wall of a private tomb ofEgypts Old Kingdom, 5th or 6th Dynasty (ca. 2494-2181 BCE), that had never been displayed due to itspoor condition.

In order to read the images and hieroglyphicinscriptions on the block, I used a technique calledReflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI). RTI usesa series of photographs to create a composite digitalimage of an object, enhanced with ideal lighting.As part of this process, I ran a public demonstrationin CultureLab, letting visitors shine the light sourceat the block from different angles.

We can now read the inscriptions on the two regis-ters on the block. The top shows six offering bearersbringing goods in the direction of the burial. Thebottom, although only partially preserved, is clearlya butchering scene, where the butchers talk incolloquial speech: one says to the other, Give methat! The other replies, I will do! This cartoon-

style captioning is typical of Old Kingdom privatetomb decoration, where scenes from daily lifeensured that the deceased would have provisionsin the afterlife.

The RTI software and equipment used for thisanalysis are now a part of the Museums analyticaltoolkit, promising other insights to be gained fromits collections.

-

NewAcquisitionsThierry Gentis

A sampling of new acquisitions (l. to r., top to bottom): Stone amulet, Taino, Dominican Republic, AD 1200-1500; Dog vessel, Colima, Mexico,100 BC-AD 250; Strawberry basket, made by Carrie Hill, Mohawk; Stone vessel, Olmec, Xochipala, Mexico, 1500-900 BC; Canoe ornament,Trobriand Islands, early 20th century; Stool, Duala, Cameroon, early 20th century; Ship cloth, Paminggir, Sumatra; Ivory seal-shaped toggle,Alaskan Eskimo, 19th century; Canoe model, Tlingit, southeastern Alaska, late 19th century; Polychrome jar, Hopi, Polaca, Arizona, early20th century; Harp, Fang, collected in Gabon in 1963-65.

Collections are the lifes blood of anymuseum. Their care,examination, exhibition, investigation, and use underlie allother aspects of amuseums activities. The HaffenrefferMuseumseeks to acquire archaeological and ethnographicobjects that serve to illustrate and document humancultures and societies worldwide; that enhance the educa-tional, cultural, or research value of the collection; thatare sources of artistic inspiration; and that can be properlystored, conserved, and preserved. TheMuseumwill notknowingly acquire materials that have been illegallyexcavated, norwill it support, in anyway,markets in illegallytrafficked antiquities. We acquire objects only whenwehave determined to the best of our ability that they havebeen collected, exported, and imported in full compliancewith the laws and regulations of the country or countriesof origin, of the federal government of the United States,and of the pertinent individual states within theUnited States.

This year saw remarkable growth in themuseumscollection with new objects from all parts of the globe Greenland to NewGuinea, Nepal to Peru withethnographic objects, stunning images, archaeologicalspecimens, and contemporary art represented. Some

highlights of this years acquisitions include 3000-year oldOlmec figures and a stone bowl fromGuerrero, Mexico;a 2000-year old stone figure also fromGuerrero; and acollection of 31 superb Taino objects from the DominicanRepublic. These objects were vetted by themuseumsCollection Committee as having been in the United Statesprior to 1970, the year of UNESCOs Convention on theMeans of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import,Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.

Themuseumwas the recipient of 50 objects fromWestAfrica donated through the generous continuing supportof WilliamC.Mithoefer and Renee-PauleMoyencourt. Thecollection includesmany examples of traditional furnitureincluding the impressive Bamileke chair fromCamerooncurrently on view in the exhibition Images of PowerinManning hall. Mr. Michael B. Tuckers gift of 67 objectsfromGabon is an important addition from an area previ-ously not well represented in themuseums holdings fromAfrica. Collectedmostly fromFang and Punu peoples,the objects were acquired as gifts and purchases in Gabonby Michael Tucker when he was working as a PeaceCorps volunteer from 1963 to 1965.

-

19

This year we decided, with generous support fromthe Office of the Provost, to convert our collectionsmanagement system from ARGUS, our currentDatabase, to Zetcoms MuseumPlus system. ARGUShas served themuseum very well over the yearsand with it we have been able to catalog more than90 percent of our collections into its database. Thelast several years have also seen the incorporationof thousands of images, which now cover nearly 50percent of our collections. This work, done by ourstaff and by students training with us as interns, hasallowed faculty and students visiting themuseumto acquire information and printouts to aid in theirresearch. It also helps us in managing loans of ourobjects to other institutions for research or exhibits,such as those this year to the Muse du Quai Branly(Paris), the Autry National Center (Los Angeles),and the New Bedford Whaling Museum (NewBedford, MA).

MuseumPlus will allow us to take this work to thenext level and offer all of our collections online forthe first time. When the conversion and onlinesystems are complete, anyone will be able to accessthe Haffenreffers collections, download photo-graphs, request loans, or create object lists fromour collections. Our goal is to open up our collec-tions to the general public and to give students,faculty, and staff at Brown a clearer understandingof what we curate and can offer them.

Our shift to MuseumPlus came after years ofresearch and consideration of databases currentlyavailable, and visits to other local institutions,including RISD, to assess and experiment with theirdatabases to gain an understanding of what wouldwork best for the HMA collections. We are impressedwith MuseumPluss capabilities and flexibility. Forthe first time, we will be able to include data fromour archives and track our collections in ways thatwere never possible before. We will start this projectin the next fewmonths and we plan to have itcomplete by the end of the year.

Managing the CollectionsNathan ArndtAssistant Curator

The Haffenreffer Museum regularly loans objectsfor exhibitions around the world: on the left, Lakota artistClaire Ann Packards Waterbirds star quilt, on loanto Paris's Muse du Quai Branly; on the right, a GreenlandicInuit childs outfit, on loan to the New BedfordWhaling Museum.

Collections

-

Over the past year, we have beenworking to identifyinteresting and historically significant archivalcollections held by the museum. These archival

collections represent much of our vastcollections history and include a wide

variety of documents, images, notes,and occasionally films or record-ings donated by collectors and

researchers that complement andcontextualize our ethnographicand archaeological collections.

Working together, we have begun toselect archival collections, both large and

small, that are ideal candidates for which tobuild finding aids. Finding aids are the fundamentalorganizational tool that archivists use to inventory,organize, and describe collections in a standardizedformat that allowsmuseums to document theirarchival collections and make them available toresearchers in the outside world. This year the

Haffenreffer Museum joined RIAMCO, the RhodeIsland Archival and Manuscript Collections Online,a virtual consortium of cultural repositoriesthroughout the state that will assist us in highlightingour extensive but poorly known archival collections.

Currently, two of themuseums archival collectionsrepresenting past Rhode Island residents arepublished on RIAMCO: one supports the collectionsbuilt by Emma Shaw Colcleugh, a late 19th and early20th century journalist and collector; the otherrepresents the work of Gino E. Conti, an artist whosecollections from the American Southwest arecurated at the Haffenreffer. Later this spring, wewillmake the archival collection of the museums firstdirector and first anthropology professor at Brown,J. Louis Giddings, accessible through RIAMCO.

To learnmore about RIAMCO, and themuseumsFinding Aids go to http://www.riamco.org.

20

HaffenrefferMuseumbecomesParticipating Institution of Rhode IslandManuscriptand Archival Collections Online. (RIAMCO)Anthony Belz,Guard/Greeter andRip Gerry, Photographic Archivist/Exhibition Preparator

Tlingit feastbowl fromSitka, Alaska,collected byEmma ShawColcleugh,whose archiveswere listedwith RIAMCO.

Workingwith ThingsArianna Riva (Brown 16),Student Collections Intern

Working at the Haffenreffer Collections Center hasbeen one of the great joys of my time at Brown.Not only have I been introduced to a broad range oftasks and procedures within themuseum sphere,but Ive been encouraged to pursue projects relatingto my own interests. One of the most satisfyingmoments of my work here was completing the initialsurvey, photography, data entry, and organizationof the museums extensive pottery collection fromthe American Southwest. Now, when I come acrossmentions of Zuni or Cochiti pottery, or images ofthese pots, I cant help but smile: the hands-on workI did with these pieces hasmademy sense of connec-tion to themmuch stronger. In addition, followingthrough with the entire project and being ableto see the pots shelved and lined up was extremelysatisfying and was a wonderful way of visualizingthe accomplishments we had achieved. I have also

undertaken projects as varied as archival slidescanning to cleaning, cataloguing and photographingcollections of Indonesian and South Americantextiles. As I continue to work at theMuseum, I hopeto involve myself in its Student Group in order toengage with my peers more about aspects of themuseums work.

-

Friends Board Jeffrey SchreckPresident

Susan HardyVice President

Diana JohnsonTreasurer

Elizabeth JohnsonSecretary

Susan Alcock

Peter Allen

Edith Andrews

Laura Berman

Gina Borromeo

KristineM. Bovy

David Haffenreffer

Rudolf F. Haffenreffer

Barbara Hail

Sylvia Moubayed

RobertW. Preucelex Officio

Mark SchlisselProvost

Daniel SmithChair, Departmentof Anthropology

Kevin Smithex Officio

Museum Staff RobertW. PreucelDirector and Professorof Anthropology

Douglas AndersonDirector, CircumpolarLaboratory and Professorof Anthropology

Kevin P. SmithDeputy Director/ChiefCurator and Editor,Contexts

Curators

Barbara A. HailCurator Emerita

Thierry GentisCurator

Nathan ArndtAssistant Curator

Rip GerryExhibits Preparator/Photographic Archivist

Carol DuttonOffice Manager

AnthonyM. BelzMuseumGuard/Greeter

Programs and Education

Geralyn DucadyCurator for Programsand Education

Kathy SilviaOutreach Coordinator

Grace ClearyEducation Program Intern

Molly KerkerOutreach Intern

Rachel ShippsOutreach Intern

Postdoctoral Fellows

Sean GanttPostdoctoral Fellowin Native American Studies

Jennifer StampePostdoctoral Fellowin Museum Studies

MuseumResearchAssociates

Michle Hayeur SmithMuseumResearch Associatein Circumpolar Studies

ChristopherWolffMuseumResearch Associatein Circumpolar Studies

Student Assistants

Pinar DurgunProctor

Jennifer ThumProctor

Connor HiltonStudent Research Assistant

Arianna RivaStudent Collections Intern

Mge DurusuCultureLab Assistant

Ximena Carranza RiscoPhotographer

Assistant guard/greetersMorayo AkandeLaura BermanAisha CannonChristina DiFabioAida Haile-MariamNora HakizmanaConnor HiltonCaroline SeylerDestin SisemoreSara TroppDaphne Xu

On the back cover (clockwise from upper left): A detail of the Chain of Office worn by Brown Universitys President, on exhibit for Browns 250th anniversary;a Maya woman in themarketplace, from an ethnographic image collection gifted to theMuseum; a 19th century Ojibwe vest on exhibit for The Big Read;contemporary ledger art by Lakota artist QuintonMaldonado and beadedmoccasinsmade by Ojibwe artist Cheryl Minnema, both purchased by theMuseum.

-

Haffenreffer Museum of AnthropologyBrown UniversityBox 1965Providence, RI 02912

brown.edu/Haffenreffer

Non-ProfitOrganizationUS PostagePAIDPermit No. 202Providence, RI