2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice Theories

-

Upload

veroo-vero -

Category

Documents

-

view

22 -

download

0

Transcript of 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice Theories

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-

1188

Jack Knetsch, and Richard Thaler 1986); res-olution of social choice problems such aslocating nuclear-waste facilities (FelixOberholzer-Gee, Iris Bohnet, and BrunoFrey 1997); public-utility regulation (EdwardZajac 1985); and labor unemployment due toefficiency wages (e.g., George Akerloff andJanet Yellen 1990). The view that By now wehave substantial evidence suggesting thatfairness motives affect the behavior of manypeople (Ernst Fehr and Klaus Schmidt1999) is expressed in mainstream economics.This contrasts with the traditional belief ofmany economists that justice is chimerical oramorphous. A more sympathetic stanceplaced it outside the domain of economics,better left to philosophers, political scientists,or sociologists. There has been a steadytrend, however, of increasing interest in and

acceptance of justice in the economics pro-fession, even partially displacing efficiency.2

This is not to say, of course, that economistsare or should be abandoning their traditional

2 This is suggested, for example, by an examination ofstudies documented on EconLit. The number of entries forthe 1970s under the keyword efficiency outnumber thoseunder justice or fairness (not counting those under theequivocal term equity) by sixteen to one. For the 1980s

this ratio falls to about nine to one, and for the 1990s thisgap further narrows to 4.4 to one. In fact, if one considersentries under the JEL classification system in operationsince 1991 through the present, hits under the code closestto justice (D63: Equity, Justice, Inequality, and OtherNormative Criteria and Measurement) outnumber thoseunder that closest to efficiency (D61: Allocative Efficiency;Cost-Benefit Analysis) almost two to one.

1 Loyola Marymount University. I thank the editor andthree anonymous referees of the Journal of EconomicLiterature; Alison Alter, Gary Bolton, John Coleman, GaryCharness, James Devine, Jon Elster, Duncan Foley, SimonGchter, Wulf Gaertner, Guillermina Jasso, Serge-Christophe Kolm, Alexander Kritikos, Axel Ockenfels, JoeOppenheimer, Richard Posner, Matthew Rabin, Erik

Schokkaert, John T. Scott, Alois Stutzer, Peyton Young, EdZajac, and participants at the meetings of the PublicChoice Society, Social Choice and Welfare Society, andInternational Society for Justice Research for many help-ful suggestions and comments. Any remaining errors orshortcomings are, of course, my own. I also thank JackKnetsch for permission to use questions from Kahneman,Knetsch, and Thaler (1986).

Journal of Economic LiteratureVol. XLI (December 2003) pp. 11881239

Which Is the Fairest One of All?A Positive Analysis of Justice Theories

JAMES KONOW1

No man during, either the whole of his life, orthat of any considerable part of it, ever trod

steadily and uniformly in the path of justice, whose conduct was not principally directedby a regard to the sentiments of the supposedimpartial spectator, of the great inmate of thebreast, the great judge and arbiter of conduct. Adam Smith (1759) p. 357

1. Introduction

Justice arguments are now widely invokedto improve theoretical and empirical analysisin nearly every field of economics.Incorporated into game theory (e.g.,Matthew Rabin 1993), fairness predicts thedeviations from pure self-interest observed inmany laboratory experiments (e.g., WernerGth and Reinhard Tietz 1990). Its impact

has also been cited in many real-world con-texts, including the intermittent failure ofproduct markets to clear (Daniel Kahneman,

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-

Konow: A Positive Analysis of Justice Theories 1189

3 There are, however, excellent surveys on more narrowtopics from which this paper has also profited, e.g.,Bernard Cullen (1994) reviews normative philosophicaltheories and Erik Schokkaert (1994) normative economictheories.

interest in efficiency. Instead, stimulated byempirical evidence and, perhaps, the percep-tion of increasing economic inequality, theyare expanding their studies to encompass awider set of distributive concerns. Despite

the emerging consensus in economics overthe relevance of fairness, though, no suchagreement yet exists among economists or,for that matter, among psychologists, politicalscientists, sociologists, or philosophers, aboutthe proper theory of justice.

1.1 Two Goals of the Study

One goal of this paper is to conduct aposi-tive analysis of leading positive and normativetheories of justice, where a remarkable lacunaexists in the literature.3 By positive analysis Imean that each theory, whether originallyconceived for this purpose or not, will beevaluated in terms of how accurately itdescribes the fairness preferences of people.In this paper, the terms fairness, justice, andequity always refer to the view of AdamSmiths impartial spectator whose judgment isnot biased by any personal stake. The discus-sion includes both distributive justice, whichconcerns fair outcomes, as well asprocedural

justice, which addresses fair processes,whereby the more extensive treatment of theformer reflects the relative emphasis in thejustice literature. Justice is operationalizedhere mostly in relation to material wealth, thechief concern of most economists, even

though it is clear that the forces discussedoften impact noneconomic domains. Otherfactors that affect allocations include altruism,reciprocity, spite, kinship, and friendship.These are significant but distinct phenomena,which nevertheless underscore the importand timeliness of studying justice, given grow-ing evidence that some behavior previouslyattributed to these forces (especially reciproc-

ity) is likely due to distributive preferences.

A second, closely related goal of the paperis to propose and defend anintegrated justicetheory that synthesizes previous approachesand explains actual values as the conflation offour distinct forces or elements. These ele-

ments of justice inspire four correspondingtheoretical categories (or families) into whicheach of the theories is placed and analyzed.The category equality and need covers theo-ries that incorporate a concern for the well-being of the least well-off members of socie-ty including egalitarianism, social contracttheories (chiefly Rawls), and Marxism. Theyinspire the Need Principle, which calls forthe equal satisfaction of basic needs. The

utilitarianism and welfare economics familycomprises utilitarianism, Pareto Principles,and the absence of envy concept, which havegrown out of consequentialist ethics, or thetradition in philosophy and economics thatemphasizes consequences and end-states.They are most closely associated with theEfficiency Principle, which advocates maxi-mizing surplus. The category equity anddesert includes equity theory, desert theory,and Robert Nozicks theory. Together theyinform the Equity Principle, which is basedon proportionality and individual responsibil-ity. The context family discusses the ideas ofKahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler; MichaelWalzer; Jon Elster; H. Peyton Young; andBruno Frey and Alois Stutzer, among others.This fourth family does not generate a dis-

tributive principle but rather deals with thedependence of justice evaluation on the con-text, such as the choice of persons and vari-ables, framing effects, and issues of process.4

4 When dealing with such an extensive literature, even awide-ranging review cannot be comprehensive. Although Ihave striven to include the most influential theories of jus-tice, some theories are omitted because they are not pri-

marily theories of justice (e.g., game theories), or becausetheir focus is more remote from the subject matter of eco-nomics (e.g., juridical theories), or because their incorpo-ration into the four elements that frame the study seemsforced (rights theories). Actually, the paper seeks to repre-sent the breadth of the literature in a relatively concisemanner by treating many theories while focusing on thoseaspects of each that contribute to the integrated theory.

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-

1190 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XLI (December 2003)

While proceeding through the sometimesintricate analysis that follows, the reader canbetter maintain a sense of unity if he or shekeeps in mind the dual goals of this paper andthe framework that structures them. On the

one hand, the specific theories discussedoffer very different, and sometimes contra-dictory, perspectives on the meaning of jus-tice. On the other hand, I argue for a generaltheory of justice as a unifying framework forthe specific theories. These ostensibly disso-nant objectives are reconciled by the follow-ing two facts. First, the general theory guidesthe classification of a specific theory into thecategory (i.e., element of the general theory)that is judged as most helpful for distilling thespecific theorys most salient contribution tounderstanding actual justice views.Nevertheless, the evidence, taken as a whole,does not confirm any single theory in toto andsometimes even refutes central suppositionsor conclusions. Both favorable and unfavor-able evidence on the specific theories, how-ever, produces lessons for the general theory.Second, it should be emphasized that thegeneral framework around which the analysisis organized is anintegrated theory, but not acomposite theory: justice is more than thesum of its parts. The three principles of jus-tice must be weighted, and context providesthe weighting scheme in specific cases. Theargument is that each category captures anelement that is important to crafting a posi-

tive theory of justice but that no single familyor theory within a family suffices to this end.Instead, fairness views are best explained byan integrated approach that acknowledgesthe influence of the three principles of jus-tice, whereby the weight on each is deter-mined by the context. This method enablesone to treat justice rigorously and to reconcileresults that often appear contradictory or at

odds with alternative theories.1.2 Reasons for this Research Agenda

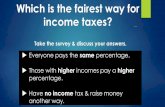

People justify their positions and behaviorin a wide range of situations based on justice,for example, in connection with affirmative

action, global warming, labor-managementconflicts, fair trade negotiations, anddebates on the taxation of income, inheri-tances, and corporate dividends. The fre-quency and vehemence of such claims, often

accompanied by sacrifices, attest to a convic-tion on the part of the advocates regardingboth their normative value and their powerto persuade and, thereby, to alter outcomes.These observations are significant becausethey indicate that fairness, in fact, appeals toa common moral sense, which, when appliedto specific cases, is subject to some interpre-tation. In particular, biases often emergewhen stakes are involved; e.g., KennethBinmore (1994) reports a strong tendency bysubjects, when debriefed following bargain-ing experiments, to describe their self-serv-ing decisions during the experiments asfair. Various studies, including those ofLinda Babcock et al. (1995), Tore Ellingsenand Magnus Johannesson (2003), and myself(Konow 2000), trace this bias in large part todeception, both of others and of oneself,regarding what is fair. These studies alsoindicate that, although biases sometimeswiden the range of predicted outcomes,behavior is still constrained by fairness.Thus, justice is not amorphous or arbitrarilymalleable, and, as I seek to show in thispaper, fairness preferences usually convergewhen stakes are removed.

These facts suggest at least two important

reasons for seeking a descriptively accuratetheory of impartial justice. First, social sci-entists must consider how justice, alone or intandem with other goals (such as self-inter-est or reciprocity), affects the phenomenathey study. Although stakeholders often sub-ject justice to biased and differing interpre-tations, in order to have moral force, theirclaims cannot be capricious but must be

constructed around impartial standards.Whereas observed behavior typically resultsfrom multiple motives, a study of impartialjustice consciously aims at separating theeffects of unbiased justice, biased justice,and other motives.

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-

Konow: A Positive Analysis of Justice Theories 1191

A second important motivation for a studyof impartial justice concerns normative andpolicy analysis in philosophy, law, and thesocial sciences. One specific purpose is in thearea of conflict resolution: given the afore-

mentioned fairness biases that often insinuatethemselves into legal, economic, and politicaldebates, impartial justice provides a standardagainst which to evaluate and reconcile con-flicting interests. In more general terms, theappropriate role of such a study for normativeanalysis depends on ones stance on certainquestions of moral epistemology (i.e., howone knows what is moral). Some scholars findthe impartial values of real people to be acompelling foundation for an ethical theory.As Tibor Scitovsky puts it, An important partof the economists task is to find out how wellthe production and distribution of goods andservices conform to the publics wishes. Thefirst thing to ascertain in this connection iswhat the publics wishes are (1986, p. 3).Philosophers, including Mill, Rawls, Nozick,and Walzer, tacitly acknowledge the merit ofthis approach by asserting that crucial prem-ises of their theories are consonant with gen-erally accepted values. Even those who wouldderive prescriptive theories in another man-ner cannot ignore the actual preferencestheir own theories will confront. As the bro-mide ought implies can suggests, any nor-mative theory with a claim to relevance mustdirect actions that are sustainable in the real

world of real values.

1.3 Empirical Method

Fairness is widely regarded as a motivebehind much behavior observed in the realworld (or the field), a view substantiated byresults of quasi-field studies that actually askimplicated parties about their motives, suchas Babcock, Xianghong Wang, and George

Loewenstein (1996); Alan S. Blinder andDon H. Choi (1996); and David I. Levine(1993). Fairness, however, is often offset orreinforced by other motives, such as self-interest, public spirit, friendship, and recip-rocal altruism (see Frey, Oberholzer-Gee,

5 Numerous studies have exposed a self-serving bias infairness judgments by stakeholders in the field, e.g.,Babcock, Wang, and Loewenstein (1996), as well as in thelaboratory, e.g., John Kagel et al. (1996) and Konow (2000).David Messick and Keith Sentis (1979) have found thisstakeholder bias even when payments are hypothetical.

and Reiner Eichenberger 1996 for an inter-esting example of how several such concernsinteract in the area of social choice).Unfortunately, field studies, though oftenuseful for demonstrating the impact of fair-

ness, are usually not designed for evaluatingtheories of fairness. Ones that elicit motives,such as those mentioned above, are few,and competing forces always threaten toundermine clear inferences about fairness.

The evidence brought here to bear on thejustice theories is marshaled from numerousstudies spanning different disciplines andemploying various methods. Because of theafore-mentioned difficulties with inferringethical intent from behavior in the field,however, the results cited are largely fromstudies that utilize experimental and surveydesigns. In moral contexts, these methodspermit better control over confounding fac-tors and stronger statements about causality.In particular, the primary goal is to track thevalues of the impartial spectator rather thanthe implicated stakeholder.5 Much of theevidence presented, therefore, comes fromstudies that encourage participants to pre-scind and abstract from personal stakes. Thesurvey method, in particular, exhibits lowself-interest bias in general attitude surveys(e.g., of support for income redistributionas in Christina Fong 2001) as well as in

vignettes, or questions that present hypo-thetical scenarios and elicit preferences over

them (e.g., Menahem Yaari and MayaBar-Hillel 1984). An advantage of experi-ments, on the other hand, is that they pro-vide behavioral measures of preferences anddemonstrate the willingness to act on themwhen stakes are involved. One drawback ofthis method for the current purpose, howev-er, is that the stakes in most experiments are

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-

1192 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XLI (December 2003)

personal and contribute to a self-servingbias. Another is that even clear departuresfrom self-interest cannot necessarily beattributed to justice as opposed to otherpreferences since motives are usually not

elicited. This paper attempts to balancethese concerns by establishing corroborativepatterns across evidence from both experi-ments and surveys.

Since many surveys and all experimentscited here use student subjects, the questionarises as to whether this group is representa-tive of the general population. In the mostcomprehensive examination of subject pooleffects in economics experiments, SherylBall and Paula-Ann Cech (1996) report theresults of various studies, including ones rel-evant to justice such as bargaining and pub-lic goods experiments, which compare stu-dent and non-student populations. With oneexception, they find little evidence of sub-ject pool effects between different popula-tions. The available evidence on such effectsfrom fairness surveys points in the samedirection. For instance, many of theKahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler (1986)results from telephone interviews withCanadian adults have been substantiallyreplicated, including with adult populationsin Germany and Switzerland (Frey andWerner Pommerehne 1993) and with U.S.adults and college students (Konow 2001,and the current study). Erik Schokkaert and

Bart Capeau (1991) relate judgments ofBelgian respondents about fair distributionsof gains and losses in diverse scenarios tosubject pool choice and to the socio-econom-ic characteristics of subjects. They compareresults from Schokkaert and Bert Overlaet(1989) with 243 college students enrolled inan introductory economics course, Overlaet(1991) with 234 parents of a different group

of economics students, and their own surveywith a representative sample of 810 adultsfrom the general population. The authorsfind that the three groups exhibit generallythe same pattern of choices and concludethat there is no need to worry about the use

of convenience samples. After biasing theirrepresentative sample study in favor of sub-ject pool effects by selecting the most con-troversial questions from the student/parentsurvey, Schokkaert and Capeau relate the

responses from the general population tosocio-economic variables including income,sex, age, education, and profession. Based onlogit estimations, they conclude that themost striking fact is the extremely smallamount of variance which can be explainedusing these equations. This is not completelysurprising It is even rather comforting inthis case: if the answers to our cases really areethically inspired, one would not a prioriexpect the socio-economic variables in ourequations to have much explanatory power(p. 337). Moreover, I will argue that, evenwhen significant differences across samplessurface, they are best explained not by dif-ferent values but by patterned variations insubject interpretation of a shared set of jus-tice principles based on differences in sub-ject information, experiences, or interests,which is entirely consistent with, indeed ispredicted by, the theory proposed here (seeespecially sections 4.2 and 5.2).

Many results cited here, including somepreviously unpublished ones, make use ofvignettes. Numerous significant economicstudies have employed this method (e.g.,Gordon B. Dahl and Michael R. Ransom1999; Kahneman and Amos Tversky 1979),

and it has proven especially useful for justiceresearch (e.g., Blinder and Choi 1990;Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler 1986;Levine 1993). Still, this method is less com-mon in economics than, say, psychology, so Iwill briefly review it and its application in thepresent study. A characteristic feature ofvignettes is their contextual richness, whichhas been shown to aid reasoning; e.g.,

William M. Goldstein and Elke U. Weber(1995) report that when a problem is pre-sented to people in abstract form, they dospectacularly bad at it, whereas when it isfleshed out with understandable content,there is remarkable improvement. In

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-

Konow: A Positive Analysis of Justice Theories 1193

6

A counterargument is that, given the above-mentioned misgivings about decision-making in abstractform, even a single vignette is more general by establishingcompelling findings in one, as opposed to no, context.Indeed, in this authors experience, conclusions based onthis method seem no less general when tested in differentcontexts and with different methods than those derivedfrom abstract questions or experimental tasks.

addition, vignettes are less prone to the mis-understandings, caused by ambiguities aboutrelevant details, that often plague otherinstruments. In fact, vignettes have beenused to improve surveys about objective

variables such as employment data (ElizabethMartin and Anne Polivka 1992). Moreover,Marilyn Lewis Lanza et al. (1997) report evi-dence that responses to vignettes closelyreflect reactions to events in the real world.An important strength of this method for jus-tice research is that it offers a flexible andeasily controlled means to provide informa-tion that can prove relevant to fairness, forexample, details about effort or needs. Theanswer formats may be qualitative or quanti-tative, but most studies cited here used theformer except where otherwise indicated. Ofcourse, a legitimate concern is that the con-tent specificity of vignettes might limit thegenerality of their results.6 A commonapproach to this question is to examine therobustness of claims through different ques-tions or versions of questions that vary con-textual elements. In fact, this also enables oneto establish evidence on the issue of whetherjustice is context specific or whether commonprinciples apply across different contexts.Another strategy is to compare results acrossstudies that employ other methods and data.Both techniques are employed in this study:for the new as well as previously publishedresults, claims are evaluated, where possible,

using multiple sources and methods.Although there exists much evidence on

justice, some theories considered here havenot heretofore been examined as represen-tations of impartial justice. For that reason,this evidence is supplemented by previouslyunpublished results drawn from a databasecontaining the responses of 3178 subjects to

numerous vignettes of the author. Thesecomprise telephone interviews with a gen-eral adult population and written question-naires completed by college students. Thesurveys were designed and conducted to

produce meaningful results and to avoidsubject pool and response biases in line withsound practices for survey research (e.g.,Floyd J. Fowler 2002, and Jon A. Krosnick1991). Fairness wording was explicitly usedfor purposes of validity, i.e., to ensure theinstrument measures what it claims to meas-ure, an important issue given evidence thatwhat is fair may differ from what is goodor what people prefer (see section 6).7

7 Other measures included the following. Different ver-sions that comprised different subsets of the master list andthat varied the order of questions aimed at avoiding sys-tematic order effects. When there were contrasting ver-sions of a scenario, each subject faced at most one versionof a scenario in order not to encourage any tendencytoward overly similar or dissimilar responses across ver-sions. A number of steps helped to minimize satisficing,i.e., suboptimal cognitive processing: scenarios were for-mulated briefly and clearly to reduce task difficulty, and

answer formats were qualitative and simple, which has alsobeen shown to improve reliability (i.e., consistency onretests). Relative to personal interviews, the telephone andself-administered surveys we used afford greater anonymi-ty and are associated with more candid responses. The tele-phone interviews were conducted on a random sample ofadults in Los Angeles, a city that, given its culturally diverseand large immigrant population, is probably more repre-sentative of the world population than most samples.Random digit dialing addressed issues of sample selection,and, to promote attentiveness, each telephone interviewposed no more than five questions and lasted no longer

than five minutes. The response rate of 47 percent, consid-ered good for telephone interviews, was achieved by briefinterviews, up to twelve attempts to contact respondentsand interviewing non-English speakers in their nativetongue. Written questionnaires were presented to studentsin a wide range of undergraduate classes at LoyolaMarymount University and lasted no more than ten min-utes. This written format was preferred for more intricatescenarios, which telephone respondents tend to processpoorly. Although the telephone interviews drew from amore general population, there were several other advan-tages of the written surveys. The questionnaires achieved

virtually a 100 percent-response rate and, by being self-administered, reduced if not eliminated possible interview-er-induced bias. More educated respondents, such as thesecollege students, are also less susceptible to various types ofsatisficing. Finally, several of the same or similar questionswere posed to both the adult and college respondents with-out large differences across samples, consistent with thefindings of Schokkaert and Capeau (1991) on this matter.

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-

1194 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XLI (December 2003)

1.4 Organization of the Paper

Section 2 addresses equality and need,section 3 covers utilitarianism and welfareeconomics, section 4 is devoted to equity anddesert, and section 5 deals with context. The

papers development resembles a Hegeliandialectic in which a theory is presented as a

thesis, often supported by evidence, only tobe confronted by its antithesis in the form of counter-arguments and evidence contrary tothe theory. Ultimately, however, the goal is toreach a synthesis of the theories at the endof each section in the form of a principle orlesson. Section 6 concludes with an even

broader approach that seeks to synthesizethe four elements of justice.

2. Equality and Need

Theories of equality and of need are usu-ally characterized by a concern for the wel-fare of those in society who are the leastadvantaged. Interpreted as a preference onthe part of real people for equally satisfyingbasic human needs, they form a principle ofjustice.

2.1. Egalitarianism

The most primitive, and probably oldest,notion of justice associates equity withequality. Justice has been construed asequality of original positions, opportunity,proportions and rights. Our discussion

begins with egalitarianism, by which I meanthe equality of outcomes. This simplest andstrongest notion of equality has often beendeclared to be one of several principles ofjustice (e.g., Morton Deutsch 1985).Equality is also sometimes taken as a point ofdeparture for studies of inequality (e.g.,Yoram Amiel and Frank A. Cowell 1999).Kai Nielsens radical egalitarian concept of

distributive justice (1985) advocates the abo-lition of material inequalities.

Some social psychologists (e.g., Deutsch1985; Gerold Mikula 1980) propose thatequality is the principle in a multi-criterionsystem that is favored in cooperative as

opposed to competitive relationships.Mikula and Thomas Schwinger (1973), forexample, study allocation decisions among36 pairs of soldiers in the same unit who per-form a task that generates joint earnings.

They find that many subjects who performwell relative to their partners act againsttheir own interests and allocate earningsequally, an effect that is stronger when sub-jects are paired with partners they like. Thisresult, which Mikula and his colleagues haveidentified elsewhere (see Mikula 1980),stands in stark contrast, however, to theself-interest bias that almost all otherresearchers find in allocation experiments(e.g., Robert Forsythe et al. 1994; ElizabethHoffman et al. 1994). The fact that eachgroup in Mikulas experiments favors a rulethat is to its disadvantage, equality by highperformers and proportionality by low per-formers, suggests that his experimentaldesign is not capturing a distributive prefer-ence for equality, which should be shared byall, but rather something closer to a gen-erosity bias on the part of both groups. Theadditional fact that this effect is strongerwhen subjects like their partners reinforcesthe impression that an interpersonal affinitydistinct from fairness is at work.

Numerous studies employing surveydesigns are unfavorable to the descriptivevalue of egalitarianism. One source of data isfrom vignette studies of micro-justice, or of

fairness to and among individuals, such asKonow (1996) and Schokkaert and Capeau(1991). These indicate a frequent preferencefor unequal allocations and that equal out-comes are only fair as a special case, e.g.,when variables subjects consider relevant tofairness happen to be equal across individu-als. Survey studies ofmacro-justice, or of jus-tice at the societal level, uniformly show

strong opposition to equal outcomes. Whenthe U.S. general public is asked about thejust distribution of income, only 7 percent of938 respondents to the survey reported inHerbert McCloskey and John Zaller (1984)and 3 percent of the 1415 respondents in

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-

Konow: A Positive Analysis of Justice Theories 1195

James Kluegel and Eliot Smith (1986) sup-port complete or near equality of income. Infact, Guillermina Jasso (1999) reports, basedon probability samples (N=8810), that ifpeople received what they consider just, the

distribution of income would be less, notmore, equal than the actual distribution ineight of thirteen countries studied.

Despite widespread evidence of supportfor departures from equal outcomes, equali-ty can, as stated above, emerge as a specialcase within a more general system, i.e., theuncontroversial concept of treating equalsequally. In other cases, equality appears tobe invoked, not as a general principle, but asa convenient approximation when the con-text renders first-best justice too complexor thorny (see section 6). If the evidencecasts doubt on equality as one of several prin-ciples, it topples egalitarianism as the singleconcern. Although complications can ariseimplementing even this simple rule (e.g.,does one equalize goods, income, or utility?),the plethora of disputes over justice suggestsit is not as straightforward as equal outcomes.

2.2. Rawls and the Social Contract

The publication of John Rawlss majorwork, A Theory of Justice, in 1971 was alandmark event in several respects. It provid-ed the principal impetus to the resurgence ofinterest in justice among philosophers, andeven many social scientists, during the twen-

tieth century. In addition, the authors of nearly every subsequent normative treatmentof justice have felt obliged to formulate theirtheories within Rawlss framework, or at leastto define their positions with reference to hiscontribution. In part a critique of utilitarian-ism,A Theory of Justice builds upon the the-ory of the social contract associated withLocke, Rousseau, and Kant. Equality plays a

central role in Rawlss theory, as does duty,including the duty to help those in need.

Rawls is concerned with social justice, ora standard whereby the distributive aspectsof the basic structure of society are to beassessed (p. 9). The principles of justice are

those that free and rational persons con-cerned to further their own interests wouldaccept in an initial position of equality (p.11). They are manifested as part of a socialcontract, or an original agreement for the

basic structure of society. This agreement ischosen in the original position, a hypotheti-cal situation in which people are behind aveil of ignorance of their places in society,i.e., their social status, wealth, abilities,strength, etc. Rawls argues that, since per-sonal differences are unknown and every-one is rational and similarly situated, thisveil of ignorance makes possible a unani-mous choice of a particular conception ofjustice (p. 140).

Competing contractarian theories of justicehave framed the question somewhat differ-ently. Binmore (1994) and David Gauthier(1985) employ game theory to examine theemergence of justice through bargaining. Inhis Treatise of Social Justice (1989), BrianBarry rejects both the Rawlsian and game-theoretic approaches and suggests that princi-ples of justice result, not from individualchoice or bargaining, but rather from debatein which others are convinced of the reason-ableness of principles, even if they run count-er to their interests. Serge-Christophe Kolmstheory of the liberal social contract (1985)departs from other contractarian theories inseveral respects. Kolms contract is an agree-ment between real parties aware of their posi-

tions and not between fictitious individualsbehind a veil of ignorance, agreements maybe reached for subsets such that not all deci-sions require unanimity, and people are moti-vated not only by self-interest but also byaltruism. As in the case of the present study,the goal of Brian Skyrmss Evolution of theSocial Contract (1996) is descriptive ratherthan normative. Specifically, Skyrms employs

evolutionary dynamics to explore the devel-opment of the existing implicit social contract.

Returning to Rawls, on whom we willfocus here, he claims two justice principleswould be chosen in the original position.The first emphasizes equality, including

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-

1196 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XLI (December 2003)

equal rights, liberties, and opportunities.The second principle (later called the differ-ence principle) has been the subject ofgreater commentary. Rawls himself statesthis second principle as the general concep-

tion of his theory: All social primarygoodsliberty and opportunity, income andwealth and the bases of self-respectare tobe distributed equally unless an unequal dis-tribution of any or all of these goods is to theadvantage of the least favored (p. 303). Thedifference principle, then, is a maximin rulefor the distribution of the goods, materialand other, that Rawls regards as primary.

The difference principle is the part ofRawlss theory that has generated the great-est volume of hostile reaction and on whichhe is generally considered most vulnerable.Kenneth Arrow (1973) and John Harsanyi(1975) raise objections from the perspectiveof welfare economics. Perhaps the mostdamaging criticism, however, is of the psy-chological assumption that people in theoriginal position prefer to maximize mini-mum outcomes to the complete exclusion ofany other goals. Norman Frohlich and JoeOppenheimer (1992; 1987 with CherylEavey) have conducted various laboratoryexperiments aimed at inducing the originalposition. University students, assigned togroups of five subjects, are introduced toand tested on their understanding of fourdistributive rules (including maximum

expected value and the difference principle).The subjects then discuss the rules. If theyarrive at a unanimous agreement, they arerandomly assigned to different income class-es and are paid according to income classand group choice of rule. Subjects almostalways reach a consensus, and the vastmajority agree to a mixed rule: maximumexpected value subject to a constraint on the

minimum income. Rawlss difference princi-ple is the least favorite rule, being chosen byonly one of 81 groups. Similar resultsemerge in experiments conducted inAustralia, Canada, Poland, Japan, and theUnited States and in a replication that

8 This might seem like a difference without a distinc-tion, but that is not so. For example, an egalitarian who isrisk-loving over his own allocations would prefer rules thatgenerate equal splits as impartial spectator but might favora very disperse distribution of outcomes in the originalposition.

purges the procedures of any explicit men-tion of justice or fairness (Paul Oleson 2001).

The experimental evidence on Rawlsianjustice seems to constitute a near-categoricalrejection of its crucial premise.

Nevertheless, legitimate questions can beraised about the efficacy of the experimentaldesign. Passing through the laboratory dooris not necessarily equivalent to passingthrough a veil of ignorance, and previously formed knowledge and expectations mighttaint subjects reasoning. In addition, thestructured discussion of the Frohlich andOppenheimer experiments resembles moreBarrys debate leading to consensus thanRawlss perfect coincidence of individualchoices. On the other hand, this aspect doesseems to err in Rawlss favor by allowing hisprinciple to be chosen even without identi-cal individual preferences. If the differenceprinciple really represents shared values, it isdifficult to grasp why, even behind an imper-fect veil, it does not emerge with greater fre-quency.

The question both Rawls and this study askis premised on a kind of impartiality. Rawlssthought experiment, however, involves indi-viduals who are presumed to have a stake inthe outcome and who, by assumption, aremotivated in their choice of principles solelyby self-interest. Our question, by contrast,concerns the choices of impartial spectatorswho are not stakeholders and who are

assumed to be motivated by social prefer-ences.8 In addition, we do not presume thatthey deliberate over or even have any explicitawareness of ethical theory, but only that theirpreferences be guided by general principlesthat can be deduced from their decisions.

The failure, therefore, of the Frohlich andOppenheimer experiments to confirmRawlss hypothesis does not necessarily rule

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-j

Konow: A Positive Analysis of Justice Theories 1197

TABLE 1. Questions 1A, 1B and 1C

1A. The owner of a small office supply store has two employees, Mike and Bill. They are equally productive andhardworking and are both currently earning $7 per hour. The owner decides to move his store to a new locationnearby where he knows business will be better. He lets his workers know that if they wish to continue at the newlocation he will be able to raise their wage. He explains that they will continue to have the same responsibilities butthat one worker will earn $8 per hour and the other $12 per hour. He also explains that which worker gets the high-er wage will be determined later on the basis of a coin toss. The workers can choose to go with the owner to thenew location under these terms or to find similar work elsewhere for their current $7 per hour. They both chooseto go with the owner. Please rate the store owners terms for the new wages as:

Fair 14% Unfair 86% N 142

1B. Suppose Mike and Bill begin working for a computer software company at the same time and in the samecapacity. Initially they both earn a salary of $50,000 per year. After a trial period Mike demonstrates that he is hardworking, productive and performs far beyond initial expectations. Bill, on the other hand, is lazy, unproductive andperforms far below initial expectations. Their supervisor decides to give Mike a $10,000 per year raise and to cutBills salary by $1000. Please rate the supervisors decision to raise Mikes salary and to cut Bills as:

Fair 80% Unfair 20% N 177

1C. Mike and Bill are identical twins who were reared in an identical family and educational environment. Theyare the same in terms of physical and mental abilities, but Mike is more industrious than Bill. For that reason, afterthey begin their careers Mike ends up earning more than Bill. Please indicate whether you view such a differencein their earnings as:

Fair 99% Unfair 1% N 1505

5

5

9 In this study, questions assigned the same number butdifferent letters (e.g., 1A, 1B, 1C) were always put to dif-ferent groups of respondents. Questions from the writtenquestionnaires are identified by italicized question num-bers (e.g., 1A), whereas ones from the telephone interviewsare identified by question numbers set in bold (e.g., 8A).

it out as a theory of justice in this othersense. A different instrument, which pur-posely seeks to elicit views of impartial spec-tators, is better suited to this objective. Inthis vein, the opposition cited to equal out-comes in the previous section is generallyunfavorable to Rawlsian justice. More spe-cific evidence is provided by the vignettes intable 1.9 Question 1A incorporates severalcharacteristics of Rawlss thought experi-

ment. Two individuals find themselves ini-tially in a situation of equality, which is fol-lowed by a randomly determined state inwhich their lots differ. Additionally, the pro-posed contract permits allocations that sat-isfy the difference principle: By acceptingthe owners offer, they will both be better offthan initially (including the least advantagedperson), and they both even demonstrate

their preference for this unequal butimproved state by choosing it over an oppor-tunity to duplicate the conditions of the ini-tial state. Nevertheless, 86 percent of the142 (N) respondents judge this contractunfair.

A possible shortcoming of question 1A isthat respondents might reason that theowners terms are unfair because they con-jecture that the owner could also choose ex

post equality by raising the wages of both tothe same level (e.g., $10 per hour). One canapproach this problem differently. Rawlsianrespondents, in keeping with the differenceprinciple, should oppose any change thatleaves the least advantaged person worse off.A corollary of this is that, beginning from aposition of equality, any change that makesone person better off while making another

worse off is not fair. Question 1B tests thiscorollary and finds that, in this context, 80percent of the 177 respondents do, in fact,support such a change, in opposition toequality and to the difference principle.Here the two parties appear similar, except

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-j

1198 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XLI (December 2003)

with regard to effort and productivity.Question 1C accentuates the equality ofstarting positions of two individuals whilefocusing on the role of differential effort,and respondents almost unanimously view

unequal rewards as fair. The latter two ques-tions highlight the fact that the drawbacks ofRawlss theory are not limited to what it con-tains but also to what it lacks. His frameworkdenies, or at least fails to assign any role to,factors not due to the vagaries of Nature.Question 1C, in particular, demonstratesthat inequalities can be fair even whenNature bestows on individuals identical abil-ities and positions.

In defense of Rawls, his goal is to describethe principles that govern the general struc-ture of society, which, he claims, might differfrom those that apply in more specific cases(p. 8), such as, perhaps, those above. On theother hand, if they are genuinely general,these principles must apply to a substantialnumber of specific cases, a point he alsomakes (p. 9), yet one is hard pressed to findevidence of significant support for the dif-ference principle. Nevertheless, otheraspects of Rawlss theory resonate with pop-ular values. In the context of duty, he stress-es the importance of helping the needy,although he grounds this rule on the self-interested desire to insure oneself againstbeing a victim of misfortune (pp. 33839).Rawlss attention to need and a kind of

impartiality probably represent his two mostsignificant contributions to justice theory.

2.3. Marxism

Justice is a highly controversial conceptamong scholars of Marxism and has beensubject to very divergent interpretations.Marxs own treatment of justice is sparse,and commentators have often read it as

rejecting justice, indeed the whole of moral-ity, as a bourgeois construct that is specificto context and history, and for whichsocialism no longer has any use. Engelswrites that justice is but the ideologised,glorified expression of the existing economic

relationships (Karl Marx and FriedrichEngels 1958, vol. 2, p. 128). Marx seems toassociate justice with rights and proportion-ality, which lead to inequalities. Instead, heendorses the communist distributive princi-

ple, From each according to his ability, toeach according to his needs! (1875, p. 531).Standing in contrast to these scant canon-

ical writings is an extensive literature onMarxian justice. Scholars of Marx have inter-preted his view of justice as, in Marxs words,obsolete verbal rubbish of capitalism(Allen Buchanan 1981), a critique of capital-ism (Gary Young 1981), a juridical ratherthan moral concept (Robert Tucker 1969;Allen Wood 1981), and a set of historically dependent principles that always reflect aconcern for equality and need (Jeffrey H.Reiman 1981). Whether or not Marx thoughtof justice in terms of need, this seems themost promising approach for a Marxian the-ory (as opposed to a Marxian critique) of jus-tice. There is no denying the centrality of need as a principle of distribution for Marx.Agnes Heller (1974), for example, writesWe can see, then, that in the new economicdiscoveries which Marx regarded as his own,the concept of need plays one of the mainroles, if not actuallythe main role (p. 25).

Experiments provide both implicit andexplicit evidence of need as a general distrib-utive concern. In the dictator experiment,one subject (the dictator) is given a fixed sum

of money, any amount of which he may sharewith an anonymous counterpart, who has norecourse. Catherine Eckel and PhilipGrossman (1996) conduct a dictator experi-ment in which some subjects allocate toanonymous student counterparts and othersto an established charity. They find donationsto the presumably more needy charities to besignificantly greater than those to fellow stu-

dents. In the ultimatum game experiment, aproposer selects an offer to make to a respon-der, who can choose to accept, in which casethe pie is divided as proposed, or to reject, inwhich no one gets anything. In the ultima-tum games of David Kravitz and Samuel

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-j

Konow: A Positive Analysis of Justice Theories 1199

Gunto (1992), responders are more likely toaccept low offers from (unknown to them,fictitious) proposers who appeal to their ownneed. Wulf Gaertner, Jochen Jungeilges, andReinhard Neck (2001) find between 66 per-

cent and 93 percent of 340 college studentssurveyed prefer funding to satisfy the needsof a handicapped child over educating anintelligent child. It is unclear, however, fromthese studies whether need is a justice prin-ciple or some other distributive motive.Moreover, studies of macro-justice paint adifferent picture. McCloskey and Zaller(1984) report that only 20 percent in theUnited States think a persons wages shoulddepend on his needs versus the importanceof his job (N=938), and only 6 percent thinkit would be fairer to pay peoples wagesaccording to economic need rather thanbased on how hard they work (N=967).Similarly, Kluegel and Smith (1986) find thatonly 13 percent of 1468 U.S. respondentsthink a persons income should be based onfamily needs rather than skills, although alarge minority of 41 percent agrees that itwould be fairer to pay people based on whatthey needed to live rather than the kind ofwork they do (N=669). These studies indi-cate that need affects distributive choicesand preferences but do not resolve whetherthat fact is related to fairness.

2.4. The Need Principle

Basic needs often factored into the writingsof political economists who lived during muchearlier stages of economic development (e.g.,Thomas Malthus 1798; Henry George 1879).Today whole nations are protected from direneed. Nevertheless, one out of every sevenpeople in the world still lives in hunger,according to a United Nations agency (www.wfp.org). The philosopher D. D.

Raphael (1980) appeals for the primacy of equality and basic needs and claims that jus-tice demands there be a basic minimum forall even if some of those affected could notachieve it by their own efforts (p. 56). Basicneeds are the material means considered as

essential for tolerable living and should besatisfied equally for all. Nevertheless, Raphaelargues one must consider not only need butalso utilitarian concerns, i.e., the effects onincentives for efficiency: Justice, then, is

thought to require a basic minimum of equalsatisfactions Above that line, room is leftfor individuals to do as they think fit (p. 54).

Raphaels comments imply, similar toRawls, a lexicographic ordering of goals:basic needs take priority over other concernsbut, once satisfied, attention turns to effi-ciency. The evidence cited above does sug-gest that people care not only about need butalso about adverse incentive effects of basingallocations solely on need, which is why theyoppose it as the foundation for a system of distribution. In addition, a scenario involvinga grant to an impoverished nation (Konow2001) provides specific evidence that satis-faction of basic needs for food, shelter, andclothing is considered fair. Moreover, asefficiency is increasingly jeopardized in thatscenario, the concern for basic needs dimin-ishes and is eventually overruled by efficien-cy, implying a tradeoff. Finally, in a survey study by Helmut Lamm and Schwinger(1980), respondents allocate earningsbetween two students who require differentamounts of money to purchase their books.Most divisions are unequal, with average allo-cations usually satisfying the differing needs.

The following conclusions seem consis-

tent with the evidence presented here.Empirical studies provide almost no sup-port for egalitarianism, understood asequality of outcomes, or for Rawlss differ-ence principle, although they do reveal aconcern for the least advantaged, in linewith core ideas of Marx, Rawls, and theirfollowers. The themes of equality and needcan be found in a more defensible rule I

will call the Need Principle: just allocationsprovide for basic needs equally across indi-viduals. Specifically, the evidence can bereconciled with a multi-criterion justicetheory in which, as suggested by Raphael,this concern tends to dominate when basic

http://www.wfp.org/ -

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-j

1200 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XLI (December 2003)

TABLE 2. Question2

2. Jane has baked 6 pies to give to her two friends, Ann and Betty, who do not know each other. Betty enjoys pietwice as much as Ann. In distributing the pies, what is fairer:A. 2 pies to Ann and 4 to Betty, or 40%B. 4 pies to Ann and 2 to Betty, or 4%C. 3 pies to each? 56%

N 2115

needs are endangered. Nevertheless, whenneeds differ across individuals, satisfyingneeds at an equal level implies unequalmaterial allocations. In addition, this princi-ple is not absolute: preferences over it are

not lexicographic but are instead consistentwith a trade-off between need and otherdistributive goals.

3. Utilitarianism and Welfare Economics

Much evidence, such as that cited in theprevious section regarding efficiency, indi-cates that people care about outcomes at thesocial, and not just individual, levels. The

theories discussed in this section share theproperty that they reflect a concern for theoverall consequences of allocations or alloca-tion schemes. In moral philosophy, thesebelong to the school of consequentialist the-ories, which judge the rightness of an actbased on its consequences. These are con-trasted, for example, with deontological the-ories, which stress the relevance of other fac-

tors, such as the Kantian concern withintentions, in evaluating the morality of anact. Most of normative economics is firmlyrooted in consequentialist ethics, havinggrown philosophically out of the Utilitariantraditions of Bentham and Mill. This isapparent in the prominent place welfareeconomics assigns to efficiency, a concernwe will consider as a principle of justice.

3.1. Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism is the leading consequen-tialist theory of ethics and the chief forebearin the lineage of welfare economics. It is themoral doctrine that one should act so as to

produce the greatest possible balance ofgood over bad, where good is understood tomean happiness or pleasure. JeremyBentham, who is responsible for the firstprecise formulation of this theory (1789),

advocated what is sometimes called act util-itarianism. According to Bentham, oneshould at every moment act so as to pro-mote the greatest aggregate happiness. Thisis contrasted with the views of anotherfamous utilitarian philosopher and politicaleconomist, John Stuart Mill, who champi-oned a version now usually called rule utili-

tarianism (1861). Mill proposed that one act

according to the general rules of conductthat produce the greatest happiness (e.g.,never lie, never steal), even if the rules donot maximize aggregate happiness in everyinstance. For Mill, justice is the mostimportant and binding subset of thesemoral rules.

Welfare economics is derived from actutilitarianism. Economic acts, i.e., choices,

are evaluated in terms of their consequencesfor social welfare. This, in turn, typicallydepends on a composite evaluation of indi-vidual welfare or utility, an approachAmartya Sen calls welfarism (1979).Classical economists, keeping withBentham, assumed individual utility to becardinally measurable and interpersonallycomparable and aggregated individual utili-

ties additively to derive social welfare.Utilitarianism implies that resources be allo-cated first to the person who derives thegreater marginal utility. Consider question2in table 2. According to utilitarianism, A isthe preferred choice among these three

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-j

Konow: A Positive Analysis of Justice Theories 1201

10 A clear and significant majority response emergesfor almost all questions in our survey. The evidence indi-cates that more evenly divided responses are due, not to

major divisions of opinion among respondents, but ratherto the fact that the views of most are close to indifferencebetween the response categories (e.g., see the results ofquestion 8 in Konow 2001; see footnote 11 for other rea-sons). The close splits found in question2 and versions ofquestion 3 are less typical but are reported here todemonstrate with brevity the effects of multiple goals orprinciples.

because the largest amount goes to the per-son who derives the greatest pleasure. Infact, a large minority of respondents (40 per-cent) identifies this as fairest. Alternative B,which is chosen by only 4 percent, suggests

equality across individuals, not at the mar-gin, but in total levels of utility, a concept ofjustice implied by Sens Weak Equity Axiom(1973, p. 18). Nevertheless, a small majority(56 percent) selects an equal split of theresource.

Utilitarianism proposes that welfare com-parisons be made, not on the basis of goodsor money, but rather using the subjectivevalues derived from goods, money, etc. Thisraises the question of the appropriatemetricof justice, that is, of the unit of account forjustice evaluation, and whether it should beallocable variables such as goods and money,or derived values such as health, satisfaction,pleasure and happiness. The results to ques-tion2 seem mixed: the majority choice of Csuggests a preference for equality in goods,but the relatively strong showing for Aimplies that pleasure has significant pull.Another possibility is that utilitarianism cor-rectly emphasizes subjective values but thatC strikes a compromise between maximizingtotal utility and equalizing utility across indi-viduals along the lines Sen suggests.

The close split on question2 is not typicalof survey findings on this issue or on fairnesspreferences, in general.10 Most evidence

favors Sens thesis. Yaari and Bar-Hillel(1984) present college applicants in Israelwith a scenario in which two individualsmetabolize the nutritional value of two foodsdifferently. Different versions of the question

11 The other questions in this study, however, generatedisperse responses, and no single category garners the sup-port of a significant majority. Yaari and Bar-Hillel concludethat The only general conclusion which we are preparedto draw from our work so far is that a satisfactory theory ofdistributive justice would have to be endowed with con-siderable detail and finesse (p. 22). Their seminal studymakes important contributions by employing survey tech-niques for the comparison of justice concepts, byapproaching fairness research as an ongoing process of dis-

covery and revision and by establishing some importantfindings in this area. I believe that the inability to drawclearer conclusions from many of their questions is proba-bly due to the facts that the theories they set out to test arenot specifically justice theories, and that many of the sce-narios are too complex for most respondents to evaluatewith reference to their moral intuition, indeed perhaps formany to evaluate by any standard.

vary the benefit to one of the individuals andask subjects to choose the fairest of fivequantitative allocations. In two versions (Q1and Q2), an identical 82 percent of therespondents (N=163 and N=146, respective-

ly) choose unequal quantities of the foods toeach person in order to equalize the totalderived health benefit to them.11 Other stud-ies provide support for the use of subjectivevalues. 69 percent of 81 college respondentsto question 1D in Konow (1996) regard asfair an unequal distribution of food that pro-duces an equal level of satisfaction. Similarly,Gerald Leventhal, Jurgis Karuza, andWilliam Fry (1980) conclude based on surveystudies that The emphasis is on equalizingthe members psychic gratification ratherthan actual outcomes (pp. 18283). Overall,the evidence suggests that derived values areimportant for justice evaluation and thatmaximization of these values holds somesway, but that fairness is associated morewith the equalization of derived totals.

3.2. Pareto PrinciplesAround the turn of the twentieth century,

Vilfredo Pareto (1906) defined a means foranalyzing social welfare that does not rest onthe strong cardinality and comparabilityassumptions of utilitarianism. Although util-itarianism continues to find its defenders(e.g., see Harsanyi 1955, 1975), the ParetoPrinciple has been more widely embraced by

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-j

1202 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XLI (December 2003)

12 The basic Pareto construct is the strong Pareto

Criterion, which states that an allocation,X, is Pareto pre-ferred to (or Pareto dominates) another, Y, if at least oneperson is better off, and no one is worse off, withXthanwith Y. The simple version of the Compensation Principlestates that an allocation,X, is preferred to another, Y, if itispotentially Pareto preferred, that is, if it is hypothetical-ly possible to undertake lump-sum redistribution fromXtoachieve an allocation that Pareto dominates Y.

economists as embodying an ostensiblyinnocuous value judgment, namely, itendorses any change that makes someonebetter off without making anyone else worseoff. Despite the fact that this concept is tout-

ed as relying on weaker informational andethical conditions than utilitarianism, certainof its deficiencies have also been noted,among others, that it does not produce acomplete ordering of allocations. In (notentirely successful) attempts to overcomethis shortcoming, variations and refine-ments, generically known as theCompensation Principle, have been pro-posed by Nicholas Kaldor (1939), JohnHicks (1940), Scitovsky (1941), and PaulSamuelson (1950). The CompensationPrinciple endorses any change in which thegains of some are more than sufficient tocompensate any losses of others, even if theprescribed compensation does not actuallyoccur.12 In a further step away from thePareto Principle, all measurable gains andlosses are often treated equally, in whichcase the Pareto Principle reduces to themaximization of allocable variables such assurplus or wealth. Pareto himself did notportray his principle as a justice theory, butthis version of his principle has been inter-preted as such, e.g., by Richard Posner in hisbook The Economics of Justice (1981).Although careful to set his views apart fromutilitarianism, Posner defends the claim that

justice be equated with economic efficiency,specifically, with wealth maximization.

Certain experimental results intimate aconcern for Pareto efficiency. In prisonersdilemma experiments subjects make adiscrete decision about whether to cooper-ate with one another, whereas in the more

continuous public goods analogues subjectschoose a level of cooperation throughamounts contributed to a public good. Ineither case, the equilibrium of rational, self-interested subjects is Pareto dominated by a

cooperative outcome. Alvin Roth (1995)reports that prisoners dilemma experimentsusually yield cooperation bounded well awayfrom both zero and 100 percent. JohnLedyard (1995) finds that total contributionsin public goods experiments typically liebetween 40 and 60 percent of the groupoptimum. These results are favorable to thePareto Criterion, although, of course, coop-eration in these studies might also be moti-vated by altruism or equity. Comparing, say,public goods experiments to dictator experi-ments, however, a distinguishing feature ofthe former is the size of total surplus, a con-cern that is reinforced by (the possibility of)partial compensation for cooperation.Moreover, public goods contributions tendto run higher than the usual average dictatorcontributions of about 5 to 25 percent.

Bargaining experiments provide morecompelling evidence of an efficiency motive.In Hoffman and Matthew Spitzer (1985) twosubjects are presented with sets of alloca-tions that generate different individual andjoint payoffs. One of the subjects is the con-troller, the person who can choose unilater-ally the payoffs. The controller is selected bywinning a preliminary game or randomly by

a coin flip, depending on the treatment. Inface-to-face negotiations, however, the othersubject can attempt to persuade the con-troller to choose specific payoffs and to agreeto transfers of payoffs between the parties.Although the controller is essentially a dicta-tor, 91 percent of Hoffman and Spitzers 86pairs reach agreements that maximize jointsurplus, and about one-half of the transfer

decisions result in equal or near equal splits,meaning that efficiency was often achievedat some sacrifice to controllers. Prompted bythe Hoffman and Spitzer experiment, PaulBurrows and Graham Loomes (1994)explore a variation that allows pairs of

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-j

Konow: A Positive Analysis of Justice Theories 1203

subjects (N 104) to engage in mutually beneficial trades from guaranteed initialearnings. They find that 97 percent of their584 negotiations maximize joint payoffs.

These experiments with direct negotiation

support surplus maximization under condi-tions that, through the availability of transfers,permit, not only potential, but actual Paretoimprovements. How is this goal affected inthe absence of transfers and direct negotia-tion? Gary Charness and Brit Grosskopf (2001) conduct dictator-like experiments inwhich the dictators face anonymous coun-terparts and select between two allocations:one gives equal payoffs to both and the otherinvolves unequal payoffs, usually favoring thecounterpart, that sum to more than the equalpayoffs. Between 66 percent and 88 percentof dictators (N 61) choose allocations thatmaximize total surplus, giving their counter-parts up to twice as much as themselves,sometimes even at a small sacrifice. Charnessand Rabin (2002) find a similar willingness tosacrifice in order to increase the total,although in the games they study this willing-ness varies with relative payoffs and with theprevious choices of counterparts. AlexanderKritikos and Friedel Bolle (2001) similarly find that 58100 percent of dictators (N 80)in a binary choice dictator game prefer allo-cations that maximize earnings over ones thatare more equal or even that favor themselves.

Perhaps the most thorough study related

to the efficiency motive is that of JamesAndreoni and John Miller (2002). In theirvariation on the dictator game, dictatorsselect gifts under conditions that differaccording to budget size and price of givingmoney to counterparts. The latter is manip-ulated in the sense that one dollar foregoneby the dictator increases the counterpartspayoff by $0.25, $0.33, $0.50, $1, $2, $3, or

$4. Andreoni and Miller find that the vastmajority of subjects (N 176) have well-behaved preferences for giving, falling intoone of three categories: about 47 percent actselfishly, keeping nearly all for themselves,30 percent tend to allocate so as to achieve

5

5

5

5

13 The weakened support in version B reflects perhapsthe view that the efficiency benefit is insufficient to justifythe inequality, whereas the increased inequality in versionC is perhaps seen as intolerably large.

equal splits, and around 22 percent act effi-ciently, tending to maximize total surplus.On average, though, dictators give them-selves a larger payoff than their counterpartswhen giving lowers or does not change the

total (at four of four such prices) and givetheir counterparts a larger payoff than them-selves when giving increases the total (at twoof three such prices).

These experiments suggest that manysubjects are motivated to maximize surplus,but they do not resolve whether peopleregard this motive as fair. In table 3, ques-tion 3, which appears in different versions,seeks to address this. Question 3A asks sub-jects to decide whether it is fair to adopt themore efficient policy X, which produces atotal of 240 but creates unequal benefits,over policy Y, which produces a smaller totalof only 200 but divides the benefits equally.Sixty-two percent of respondents deem thechoice of the efficient policy fair.Nevertheless, this support is quite labile, asrevealed by two other versions of the ques-tion. These versions are identical toA exceptfor variations in the size of the total benefitsfrom policy X, which are identified by itali-cized passages. In version B the total under

X decreases to 210, whereas in C the totalunderXrises to 290, and in both cases sup-port forXslips versus versionA.13 Althoughthese shifts are not significant, strongerresults have been reported for a similar sce-

nario. Four versions of question 5 in Konow(2001) identify solid support for the strongPareto Criterion but weaker backing for theCompensation Principle. Moreover, thefragility of efficiency as it conflicts withother principles of justice is demonstratedthere by statistically significant shifts insupport across versions.

At the macro level, efficiency appears to

figure more prominently in views of fairness.McCloskey and Zaller (1984) report that 78

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-j

1204 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XLI (December 2003)

TABLE 3. Question 3

3A. Suppose, as used to be the case, that the US government makes land available to farmers at no cost providedthey reside on their claim and cultivate it. Each farmer may sell whatever he produces. Suppose as well that thereare just two applicants, Farmer Adams and Farmer Brown, interested in two tracts of land, 1 and 2. Tract 1 is moreproductive than tract 2 and the tracts are located too far apart for one applicant to work both. The government maychoose among one of the following two policies,Xor Y:X. Farmer Adams gets tract 1 and produces 150 bushels of wheat and Farmer Brown gets tract 2 and produces

90 bushels for a total of 240.Y. Farmer Adams and Farmer Brown share tract 1 evenly whereby each then produces 100 bushels for a total

of 200.The government chooses policy X. Please rate this as fair or unfair:

Fair 62% Unfair 38% N 104

3B. X. Farmer Adams gets tract 1 and produces 120 bushels of wheat and Farmer Brown gets tract 2 and produces

90 bushels for a total of 210. Fair 52% Unfair 48% N 105

3C. X. Farmer Adams gets tract 1 and produces 200 bushels of wheat and Farmer Brown gets tract 2 and produces

90 bushels for a total of 290. Fair 55% Unfair 45% N 1095

5

5

percent of 938 respondents find that Undera fair economic system people with moreability would earn higher salaries. This ispresumably because, as 85 percent of 967persons surveyed agree, Giving everyoneabout the same income regardless of thetype of work they do would destroy thedesire to work hard and do a better job.

3.3.Absence of EnvyThe theory of fairness with the purest eco-

nomic pedigree, and the usual definition ofequity in welfare economics, is the absenceof envy criterion. The concept was first for-mally stated by Duncan Foley (1967) andwas further developed by Hal Varian (1974),Elisha Pazner and David Schmeidler (1978),William J. Baumol (1986), and others. Part

of the motivation for this research agenda isas a way to narrow the set of permissiblePareto optima, thereby identifying alloca-tions that are both efficient and equitable. Inthe simplest form, an allocation is envy-freeif no agent prefers (i.e., envies) the bundle of

another. The no envy criterion has been gen-eralized to include considerations of numberof agents, groups of agents, common choicesets, envy-free trades, leisure, output andlabor ability and has spawned the concept ofegalitarian equivalence.

Absence of envy is an appealing constructand seems like a reasonable goal. The ques-tion asked in this study, however, is whether

it describes allocations people call fair, orwhether it is distinct. Robin Boadway andNeil Bruce (1984) are skeptical about equat-ing the two: I might envy a friends luckyfind in an antique store yet perceive nounfairness that he, not I, owns it (p. 175).This inspired question 4 in table 4, whichtests the simple envy-free concept thatapplies to final allocations only. Even though

respondents are encouraged in this scenarioto envy the others allocation, a sizable 87percent judge it fair. It is possible, though,that respondents would be envy-free if oneinterpreted the bundle more broadly, e.g., toinclude the time spent searching for the

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-

Konow: A Positive Analysis of Justice Theories 1205

TABLE 4. Questions 4 and 5

4. You and an acquaintance would both like to have a rare record album. Your acquaintance spends several hoursa week looking in used record stores whereas you never bother to look. The acquaintance finds the album.

Fair 87% Unfair 13% N 299

5. Chris, who is blind, does not like TV and Pat, who is a vegetarian, does not like hamburger. Suppose that Chrisand Pat work for the same company in the same capacity and earn the same base salary. The time comes for theend of the year bonus. Chris, who works much harder than Pat, receives a $2 coupon for a hamburger. The lessproductive Pat, on the other hand, receives as a bonus a $2000 wide screen television.

Fair 10% Unfair 90% N 2605

5

14 I am indebted to a referee for this point.

album.14 Question 5, also in table 4, howev-er, is free of this concern. In this scenario,although one person works harder, bothindividuals receive as bonuses goods that theother could not possibly desire regardless ofwork effort, but 90 percent of respondentsfind this unfair.

Absence of envy is questionable not onlyas a description of justice but also of what ismeant by envy in common parlance: it seemsquite possible that I would like to haveanother persons allocation, but that I do notexperience the resentful feeling about hisadvantage that the word envy typically con-notes. Randall Holcombe (1997) similarlyrejects equating fairness with absence ofenvy. He faults the envy-free criterion forexamining only outcomes and argues thatjustice requires that one look at the processby which the outcome obtains. This seemsconsistent with the results of questions 4 and

5, in which rewards conflict with individualcontributions. These results support theclaim that justice requires consideration ofrelative merits associated with the process bywhich outcomes are generated as well as ofthe magnitude of the outcomes.

3.4. The Efficiency Principle

Various studies have demonstrated that

people often seek to maximize surplus,sometimes at a personal cost, and that thisgoal is regarded as fair. These findingssuggest that efficiency in this sense is not

necessarily at odds with justice but instead isitself a type of justice. Results reported inMcCloskey and Zaller (1984) show that effi-ciency figures prominently in popular con-ceptions of a fair economic system. At themicro-justice level, however, support for thePareto Principles is sensitive to the size ofbenefits, and other results (Konow 2001)indicate that efficiency can be overturned bycompeting justice principles. Utilitarianismchallenges us to think of efficiency, and jus-tice, not only in terms of goods or wealthbut, where possible, of the subjective valuesderived from them. The metric, or the unitof account, of justice turns out to be animportant issue and one to which we willreturn in section 5. The evidence in this sec-tion also indicates that the maximization ofderived values does exercise some pull onviews of justice, although the mixed resultssuggest that, as with goods or wealth, the

maximization of these values is not the sin-gle goal of fairness. Many of the counterex-amples to efficiency point toward equalizingvalues, which seems to contradict the rejec-tion of egalitarianism in section 2. As we willsee in the following sections, however,equality can be relegated to a special casewithin justice principles that generally callfor inequality. The evidence on the absence

of envy criterion underscores the main con-clusion of this section: although justicerequires consideration of the consequencesof acts, specifically, of the size of total sur-plus, the efficiency criterion is too austere toserve as a general theory of justice. One

-

5/25/2018 2003_Konow_Which is the Fairest One of All_A Positive Analysis of Justice The...

http:///reader/full/2003konowwhich-is-the-fairest-one-of-alla-positive-analysis-of-j

1206 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XLI (December 2003)

must also attend to the process by whichoutcomes obtain, and this is central to thetheories discussed in the following section.

4. Equity and Desert

The common thread in this class of theo-ries is the presumed dependence of fair allo-cations on individual actions. This contrastswith the motive investigated in section 2 tosatisfy needs or in section 3 to maximize sur-plus, with nonecessary dependence on indi-vidual actions. Theories of equity and desertare the intellectual progeny of two philosoph-ical traditions: the distributive justice theoryof Aristotle and the natural law/desert theoryof John Locke. This section presents theoriesand explores evidence on the questions of desert, i.e., which individual characteristicsare relevant to justice, and of equity, i.e.,what, exactly, the functional relationship is ofindividual characteristics to just allocations.

4.1.Nozick