1990 Mandatory Audit for Cost and Management Accounts

-

Upload

norashikin-kamarudin -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of 1990 Mandatory Audit for Cost and Management Accounts

-

8/2/2019 1990 Mandatory Audit for Cost and Management Accounts

1/7

10 MANAGERIAL AUDITING JOURNAL 5,3

MandatoryAudit forCost andManagementAccountsB.C. Ghosh, J.G. Oliga and B. Banerjee

s a mandatory audit a preposterous ideaor the ending of an anachronism?

Although there are ongoing debates about the m erits anddemerits of (financial) accounting regulation, today it isa fact of life. Financial accounting standards governpreparation of published financial statements, and theseare subject to mandatory, statutory audit. The object ofsuch regulation is to make firms report more fully, m oreaccurately, and more truthfully and fairly than mightotherwise b e, all for the purpose of protecting the publicinterest as well as inducing investors' and other externalusers' confidence in the credibility of the financial reportingsystem. But these regulatory measures do not apply tothe second wing of accounting, the internal, cost andmanagement accounting system. The difference intreatment is presumably based on the fact that the productof financial accounting is primarily intended for externalusers, while that of cost and management accounting isfor private, internal use. This article offers, from bothconceptual and institutional standpoints, an exploratorydiscussion of the idea of extending mandatory audit to costand management accounts. What emerges from thediscussion is that the idea of mandatory audit for internalaccounting information poses a formidable dilemma: it isconceptually compelling and yet practically problematic.

The article illustrates this dilemma by citing the case ofIndia, the first country ever to legislate mandatory auditfor cost accounts, but only for specified industries andnot on a continuous, annual basis. Interviews with anumber of Indian industrialists about their experience andviews on the merits of auditing cost accounts as legislatedby the government revealed mixed reactions, evidence ofthe presence of a deeply perceived dilemma. The articleconcludes that the whole idea, far from beingpreposterous, is conceptually compelling. But, from aninstitutional standpoint, it could be that the presentworldwide practice of no requirement for the mandatoryaudit of internal cost and management accounts is ananachronism. The implication is that perhaps more studiesin the future should begin to address this seeminglyintractable issue.Financial versus Management AccountingPrivate sector or enterprise accounting has conventionallybeen dichotomised into the external wing (financialaccounting) and the internal wing (managementaccounting). While the former represents externallyoriented financial information and reporting, mainly forexternal users, the latter is concerned with internallyoriented accounting information for (managerial)organisational decision making and control. This dichotomyhas led to a corresponding difference in the legislativetreatment of the two wings for purposes of statutory audit.Statutory audit is mandatory for the external wing. Theinternal wing is considered a purely private matter, andas such falls outside the purview of public concern andregulation. However, does this orthodox accountingscenario have valid conceptual foundations? Specifically,is the very notion of a dichotomy conceptually tenable inrelation to this domain of social activity? In the nextsubsection, we examine the notion of dichotomy againstthe alternative notion of "dialectic" as a means ofilluminating, from a conceptual standpoint, the problemof differential audit treatment for the two wings.Dichotomyor Dialectic?That many systems exhibit tendencies, mechanisms,processes or forces that constitute opposing polaritiesdoes not seem to be in dispute. It is, however, the wayof conceptualising the nature of those polarities in differentcontexts that is the cause of much controversy andconfusion. Specifically, under what circumstances is it validto speak of a polarity as a dichotomy, a simple continuum,or a dialectic[1]?Voorhees[2] has made an important contribution to theanalysis of three approaches to unity in term s of duality.First, the positivist conception of polarities is in termsof dichotomies. This is an either/or classificatory approach,in which each pole is different and subsists for itself,without any essential need to be referred to the o ther :a case of mutually exclusive opposition[3]. The structuralistperspective, however, sees the positivist conception as

-

8/2/2019 1990 Mandatory Audit for Cost and Management Accounts

2/7

MANDATORY AUDIT FOR COST AND MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTS 11

inadequate to cover two other cases : the both/andsituation, and the neither/nor situation. The both/and caseis a situation of inclusive opposition, where each opposingpole constitutes a negation of the other, such that eachopposite is nothing in itself and for itself and hencemeaningless except by implying a relation to the other[3].The underlying logic here is the Hegelian dialecticalreasoning that translates into the discursive formula :thesis + antithesis = synthesis. The neither/nor approachextends the dialectical logic by including cases wherechange is instantaneous and discrete (quantum changes,as in mutations) [2].While the structuralist perspective provides an importantpointer to the limitation of the positivist concept of dichotomy,the role of human agency is conspicuous by its absence.Both perspectives rely on one or another of nature'sdimensions of space, time and cycles. In contrast, theinterpretative approaches seek to ground the explanationof opposing polarities not only in constraining objectivereality, but also in the active role of human agency.From an interpretative point of view, Gharajedaghi[4] hasgiven an insightful elaboration of the nature of polarities,clearly distinguishing between the unidimensional and themultidimensional concepts of opposing realities. Dichotomyas a unidimensional concept treats polarities as if they wereall isolated (independent), discrete entities. For instance,the polarity in the statement that "a person is either deador alive". A simple continuum, although still uni-dimensional, recognises the possibility of gradationsbetween the two extremes (e.g. relatively tall/short). Butit is only the dialectic that recognises the multi-dimensional nature of polarities, and the mutualinterdependence of their opposing tendencies, which notonly co-exist and interact, but also form a complementaryrelationship (e.g. the north and south poles of a magnet,stability/variation tendencies, fragmentation/integrationtendencies, etc.). Thus, in a context of social conflicts,Gharajedaghi sees dichotomies as representing no morethan a win/lose struggle situation which calls for a solutionin terms of the best possible outcome for one side at thecost of the other. Simple continua call for a compromiseor resolution of the conflict, which is nothing more thana superficial integration of the opposing sides . It is onlythe dialectic that permits the possibilities of a win/winstruggle (as well as lose/lose and win/lose possibilities);in this case, the conflict can be dissolved (i.e. removed)in such a way that a new framework that encompassesboth poles emerges from the discursive process of"thesis-antithesis-synthesis".In relation to the so-called two wings of accounting, it cannow be argued that they constitute not a dichotomy buta dialectic. As such, differential audit treatment wouldappear to be conceptually unwarranted. In the first place,the so-called two wings reflect but two moments whichconstitute a unity in the circuit of capital, from exchangeto production and back to exchange, cf.[5]. The externalwing highlights the "exchange moment", the humanactivities that reflect the interfacing of the system with

its environment (constituents). In the input-transformation-output model of organisational activities, the external wingfocuses on the transformation of money capital tocommodity capital (inputs) and commodity capital backto money capital (outputs). T he internal wing, on the otherhand, is essentially concerned with the "productionmoment", where commodity capital as inputs istransformed into productive capital for the purpose ofcreating new commodity capital with higher added value.Without this unity between the exchange and productionmoments, the very circuit of capital is inconceivable. Eachmoment presupposes the other, and has no meaning inand of itself. Thus, from a conceptual standpoint, thesupposed dichotomy invalidly truncates the recursivecircuit of capital, thereby ignoring the importance of therelationship between the notions of efficiency (as reflectedin the production moment) and effectiveness (the exchangemom ent). And yet both notions are presupposed in thevery purpose of mandatory audit for financial accounting."Truth and fairness" in statutory audit are, in the finalanalysis, vicarious notions for the state of organisationalefficiency and effectiveness, at least to an extent.Certification by auditors, for instance, of a company'simproved performance will make it more credible toinvestors.In the second place, the differential treatment ignores theautopoietic (the need for living systems continuously torenew themselves) nature of social systems[6-9]. Theinherent open-closed duality of autopoietic systems (ahuman organisation is supposedly such a system) impliesthat the autonomy characterising the internal reproductiveprocesses of organisational closure is just as essential asthe dependence that derives from the openness of asystem to its external environment.As Bednarz[9, p. 60] cogently elaborates, autopoieticsystems are characterised by the simultaneity of opennessand closure. They are "open with respect to structuralinteraction with the environment, and closed with respectto organisation". For accounting, the external wing reflectsthe "open" moment; the internal wing the "closed"moment, which is "intrinsically self-referential" [9, p. 58].Both moments constitute a unity which cannot bedichotomised for differential treatment.A third aspect of the dichotomy is that the differentialtreatment ignores the reflective-constitutive dialectic,whereby internal transformation processes necessarilyhave important, and yet often unintended, consequencesfor the external. In his structuring theory, Giddens[10]has extensively elaborated on the nature of the relationshipbetween the constitution of agents and external socialstructures. The two represent a duality in which structureis a medium as well as an outcome of action. In accounting,the external wing focuses on the social structural aspects,while the internal wing is more concerned with the active(autonomous) aspects of human agency and action.However, the internal self-referential activities influenceand shape the nature of the external output-environmentinterface which in turn influences the internal wing. T hus,

-

8/2/2019 1990 Mandatory Audit for Cost and Management Accounts

3/7

12 MANAGERIAL AUDITING JOURNAL 5,3

the differential treatment of the two wings is conceptuallyindefensible.Institutional Dilemm aHowever, social science debates are seldom settled onthe basis of conceptual considerations alone. Normativequestions and policy considerations are often morecompelling. Similarly, this debate faces a formidableinstitutional dilemma. On the one hand, the idea ofmandatory audit for the internal wing is simply a logicalextension of the societal desire to foster optimal allocationand utilisation of scarce economic resources. The presentworldwide practice of ignoring the internal wing for auditpurposes naively assumes that reactive responses byorganisational constituents (actual and potential) constitutea necessary and sufficient control mechanism. Obviously,while the "n ec es sary" part of the social control conditionis not in doubt, the "sufficient" part is seriously doubtful.One cannot just assume that internal controls currentlyin place in an organisation are sufficient for its purpose.A properly constituted internal audit system will certainlyhelp in this matter but existence of such an internal controlsystem cannot be taken for granted in all situations(certainly not in a developing country context). Besides,though internal auditors in certain circumstances can domore than external audit, their independence may still bedoubted. Hence organisations and their management m ustalso be made to respond in specific ways as a result ofrevelations from mandatory audits of internal cost andmanagement accounts.On the other hand, one has to accept that, in a free marketeconomy, the operation of these very agencies is predicatedupon the need for individual autonomy and the spirit ofenterprise to innovate, initiate and experiment. This isincompatible with an all-embracing regulatory framework,which is likely to stifle the entrepreneurial spirit,encouraging instead conformity and bureaucratic behaviour.In other words, the entrepreneurial decisions on how torun one's business would be seriously compromised bythe framework of a regulatory straitjacket.It is this institutional dilemma that perhaps accounts forthe present differential audit treatment. However, morethan two decades ago, one country (India), in a pioneeringmove, sought to break away selectively from thisorthodoxy. We now look at this Indian experiment.The Indian ExperimentTwo years after independence from the British, theGovernment of India set up its first professional accountinginstitute, The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India(ICAI) by Act of Parliament in 1949. Shortly thereafter Indiafelt the need for a separate institute to oversee thedevelopment of cost and management accounting practicesin India, chiefly (to begin with) in the state-ownedmanufacturing companies in many sectors. So, in 1959another institute, namely The Institute of Cost and WorksAccountants of India (ICWAI), was established by the

Government of India by Act of Parliament. Since then, costand management accounting has made significant progressin India. In particular, cost audit has been made mandatoryin large segments of industry in India.The ICWAI has been engaged in a number of governmentactivities such as the Panel for Rehabilitation of SickIndustry, Fixation of Prices, Electricity Tariff Commission.These are mainly socialist ideas, a hallmark of the nation.It is at present seeking a role in the following areas too[11]:

(1) valuation of inventories by practising costaccountants before the annual accounts are certifiedby the financial auditors;(2) mandatory employment of qualified cost account-ants in organisations of a certain minimum size;(3) monitoring of loans given by state-owned financialinstitutions;(4) appointment of cost accountants in practice asnominee directors on the Boards of Sick Industries(these are companies which are not profitable butthe Government wants them to continue to provideemployment).

As a result of the efforts made by the ICWAI, theDepartment of Tourism has accepted the proposal that,besides chartered accountants, cost accountants in practicecan now certify room tariff earnings in all hotels. TheFertiliser Co-ordination Committee under the Ministryof Fertilisers and Chemicals have included certification offertiliser pricing by practising cost accountants. Fertiliserprices are subsidised in India. Several other developmentstook place at the instance of the ICWAI. However, herewe focus upon one significant aspect only, namely, theauditing of cost accounts.The need to introduce the auditing of cost accounts wasrecognised in the late 1950s by several influential membersof the accountancy profession in India. They felt that th iswould make it imperative for companies to maintainappropriate cost records in a systematic manner. TheCouncil of ICWAI thus insisted that cost accounts shouldbe maintained on a generally accepted basis and that, oncethis was done, an audit of cost accounts should also becarried out so that areas of weakness could be broughtto the attention of company management.Because of these efforts, we now find a provision in theIndian Companies Act for maintenance of cost records byselected companies in a prescribed manner as and whenfelt necessary. By another provision in the said Act, theGovernment has also assumed power to order audit ofthose cost accounts by a qualified person. We now dealwith these legal aspects relating to the maintenance ofcost records and their audit.Power to Order Cost AuditThe power to order cost audit is contained in Section233-B of the Indian Companies Act 1956. This wasintroduced in 1965 and was the firstof its kind in the world.

-

8/2/2019 1990 Mandatory Audit for Cost and Management Accounts

4/7

MANDATORY AUDIT FOR COST AND MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTS 1 3

The prerequisite of a cost audit is the maintenance ofproper books of accounts which are required to bemaintained by rules prescribed under Section 209(1)(d)of the Act. Section 209(1)(d) states that:Every company shall keep at its registered office properbooks of accounts with re spect to : in the case of a companypertaining to any class of companies engaged in production,processing, manufacturing or mining activities, suchparticulars relating to utilisation of material or labour or toother items of cost as may be prescribed, if such a classof companies is required by the Central Government toinclude such particulars in the books of accounts.

The relevant portion of section 233-B, as amended to date,reads as follows:Where in the opinion of Central Government it is necessaryso to do in relation to any company required under clause(d) of subsection (1) of section 209 to include in its booksof accounts the particulars referred to therein, the CentralGovernment may, by order, direct that an audit of costaccounts of the company shall be conducted in such manneras may be specified in the order byan auditor who shall bea cost accountant within the meaning of the Cost and WorksAccountants Act 1959. Where sufficient number of costaccountants are not available for conducting the audit of cos taccounts of companies, the Government may by notificationin the Official Gazette direct that, for such period as maybe specified in the said notification, such CharteredAccountants within the meaning of the CharteredAccountants Act, 1949, as possess the prescribedqualifications may also conduct the audit of the cost accountsof companies.

The auditor under this section, i.e. the section relatingto cost audit, shall be appointed by the board of directorsof the company with the previous approval of CentralGovernment. An audit conducted by an auditor under thissection shall be in addition to an audit conducted by anauditor appointed under section 224, i.e. normal annualaudit of company accoun ts. An auditor for cost accountsshall have the same powers and duties in relation to anaudit conducted by him under this section as an auditorof a company has under sub-section (1) of section 227,i.e. normal company audit, and such auditor shall makehis report to the Central Government in such form andwithin such time as may be prescribed and shall also atthe same time forward a copy of the report to thecompany. The addition of a proviso to subsection (2) tosection 233-B requires that, before the appointment ofany auditor is made by the Board, a written certificateshall be obtained by the Board from the auditor proposedto be so appointed to the effect that he is entitled to beso appointed.Th e Governm ent of India has also issued Cost Accounting(Record) Rules for maintenance of cost statements forvarious industrie s. Up to M arch 1987, 35 industries havebeen brought under the purview of Cost Accounting(Record) Rules. They are (ICWAI, 1986-87) Cement,Cycles, Rubber Tyres and Tubes, Caustic Soda in anyform, Room Air-conditioners, Refrigerators, AutomobileBatter ies, E lectric lamps, Electric Fans, Electric M otors,

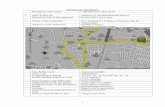

Motor Vehicles, Tractors, Aluminium, Vanaspati, BulkDrugs, Sugar, Infant Milk Food, Industrial Alcohol, JuteGoods, Paper, Rayon, Dyes, Soda Ash, Nylon, Polyester,Cotton Textiles, Dry Cell Batteries, Sulphuric Acid,Electric Tubes and Pipes, Power-driven Pum ps, InternalCombustion Engines, Diesel Engines, Electrical Cablesand Conductors, Ball and Rubber Bearings, and Milk Food.Th e ICWAI has be en actively pursuing with the CompanyLaw Department the case for also including the plasticsindustry, mini-steel plants, the general engineeringindustry, polymer and chemical industry under CostAccounting (Record) Rules. According to informationavailable to the authors up to 31 March 1987, 5,367 unitsin 34 industries were covered by these rules as shownin Table I below.Table I. Annual Number of Establishments (Units)Covered under the Cost Accounting (Records)Rules in the 1977-87 Period

Calendar Year

19771978197919801981198219831984198519861987

No. of Units Coveredunder Cost Audit49 070 736 643274535640 545 746 847246 9

5,367Source: Professional D irectorate of ICWAI Various Issues:1977-87.Note: Thus, on average, 481 units per year have been broughtunder the purview of Record Rules during 1977-87.

As pointed out earlier, under Section 233-B, theGovernment issued from time to time, as a secondarystep, orders under section 233-B for cost audit in theselected industries falling un der the purview of the rec ordrules . Accordingly, th e s tatuto ry c ost audit has so far onlybeen selective. It is also not necessary that a cost auditof a company be conducted every year as a regularfeature: 458 and 462 cost audits were ordered by theGovernment during 1985-86 and 1986-87, respectively.But in 1987-88 the number exceeded 1000. The se costaudits, however, are restricted to periods as specifiedin the order, usually the last financial year cost recordsof the company.

-

8/2/2019 1990 Mandatory Audit for Cost and Management Accounts

5/7

14 MANAGERIAL AUDITING JOURNAL 5,3

Cost Audit as an Annual FeatureAt present, many companies do not maintain any costaccounting records in the year in which there is nomandatory cost audit. But, for conserving the scarceresources of the country, or for utilising them to the b estpossible advantage, the ICWAI has been insisting onregular maintenance of proper cost accounting records anda continual cost audit. After all, this must have been thebasic rationale for the introduction of new legislativemeasures. Way back in 1978, a high-powered ExpertCommittee on the Companies Act and the MonopoliesAct (known as the Sachar Committee) recommended,among other things, continuous audit both as a step inthe direction of consumer protection and as an advantageto the company itself. The matter hasbeen pending beforethe Government of India since then. As an interimmeasure, the Government has recently agreed to ordercost audit on a biennial basis.

Cost Accounting Records and AuditThe ICWAI has so far published 30 booklets giving detailsof cost accounting records requirements and cost audit(report) rules relating to various industries. A typicalbooklet will have the following sections:(1) A brief summary of the industry.(2) Key points regarding cost accounting and cost auditrequirements in the industry.(3) A recommended costing system.(4) Guidelines for a cost audit programme.(5) Cost accounting records rules as prescribed for thatindustry by the Department of Company LawAffairs.

The prescribed rules will typically require records to bemaintained with respect to (among others):(1) Raw materials, consumables store s, wastages andrejections, etc.(2) Salaries and wages including overtime and piece-rate wages earned and any wages and salaries tobe allocated to capital works.(3) Service department expenses and the bases forequitable apportionment; the amount to becapitalised should be shown separately.(4) Utilities consumed, e.g. water, power, steam, etc.(5) Workshop repairs and maintenance and the basesfor charging out these expenses to various

departments/jobs.(6) Depreciation.(7) Works administration, selling and distributionoverheads and the bases for their absorption onjobs and capital works.

(8) R&D expenditure.(9) By-products and the bases for their valuation.

(10) The methods followed for valuation of WIP andfinished products.(11) Cost statements.(12) Intercompany transactions, etc.

The possibility of widening the scope of cost audit canbe better understood from a reading of clause 16 of theAnnexure to the Cost Audit Report, as laid down by CostAudit (Report) Rules 1968, under the heading "Auditor'sobservations and conclusions". It includes, amongstothe rs, suggestions for improvements in performance, ifany, by:(1) rectification of general imbalance in productionfacilities;(2) fuller utilisation of installed capacity;(3) concentration of effort on areas offering scope for(i) cost reduction, (ii) increased productivity, (iii)removal of key limiting factors causing productionbottle-necks;(4) improved inventory policies.

It shows that a cost auditor may go well beyond the m erequestion of maintenance of prescribed records in a propermanner so as to give a " true and fair" view of the costof production activities and the marketing of the product.This is a daring vision and intent of considerablemagnitude. Is it likely to succeed? Is it worth emulatingelsewhere?Lacunae in Cost Audit Report Rules and Cost AuditIt is not the intention of the authors to give a conclusiveopinion on the suitability o r otherwise of this concept ofmandatory cost audit. Nevertheless, a few drawbacks ofthe present system deserve mentioning.All companies engaged in production, processing,manufacturing and mining activities are not yet coveredby Cost Accounting (Record) Rules, as may have beenintended under section 209(1)(d). And, why is the serviceindustry excluded, given its significance in India today?Indian hotels are notorious for overcharging, for instance.Prescribing separate ru les for each industry involves toomuch time, effort and delay. Instead, rules could perhapsbe standardised for a group of industries like Engineering,Chemical and Process, Mining, Textiles, etc.When there is no cost audit there is a provision forcertification by the financial auditor of the Companyregarding maintenance of cost accounting records on thebasis of prima-facie evidence of maintenance of costrecords. But in many cases the reality is otherwise.

-

8/2/2019 1990 Mandatory Audit for Cost and Management Accounts

6/7

MANDATORY AUDIT FOR COST AND MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTS 1 5

In the rules framed so far, there is no scope for gettinginformation on variable costing, which may be useful forthe cost auditor in his comment on pricing policiesfollowed. And, although standard costing is alreadyaccepted by the Government as a basis for inventoryvaluation, there is no provision to report how variancesare analysed and what steps are taken on them. Further,the previous year 's figures are not required to be includedin the Report. Thus, a comparative picture on costs cannotbe obtained.A firm of cost accountants cannot undertake cost auditin its own name. This acts against proper developmentof the profession of cost audit as an individual cost auditorcannot afford to maintain a permanent establishment unlesshe is assured of continuous work to sustain it. It is alsointeresting and perhaps significant to note that theshareholders do not have, as a m atter of right, access tothe cost audit report.But many of the above can be overcome by suitableamendments in the Act or in the Cost Audit Report Rules.The experience gained by the industry on the one handand the Company Law Board and the ICWAI on the othermay be taken into consideration while taking any furthersteps in the matter. Before we conclude, a few lines onthe industry view may also be pertinent.

The Industry ViewThe authors interviewed, as a separate exercise, 14 seniorindustry officers, mainly from the eas tern parts of India,and their views on the mandatory maintenance of costrecords and cost audit can be summarised as follows: Good management is not proper maintenance ofcost and management accounts alone and theGovernment has assumed a somewhat paternalisticrole in this respect. Some agree that without legislation it could havebeen a long time before some of the companiesmaintained proper management accounting records;once having maintained them, however, theydiscovered their usefulness. A proper database is now available to manycompanies for short- and long-term decision makingand pricing decisions. The cos t of record maintenance has gone upsignificantly. There is an uneasy feeling about possible futurefurther Government intervention. Some of the requirements should be simplified andthere ought to be continuing research in thisrespect.

Proliferation of audit in this fashion is unhelpful.Management accounting is a matter of internalmanagement and decision-making support. Some regarded the whole proposition as atrocious.

Some also thought that information obtainedthrough cost audit may be abused by theGovernment (it is of interest that Chakrawarty[12]reported that India's Income Tax Department hasused cost audit reports to detect hidden profits).

SummaryWe have mentioned earlier tha t, in the Indian experiment,cost audit reports go well beyond financial audit and th einformation contained in the cost audit repor ts disclosessuch matters as operational inefficiencies regarding theutilisation of installed capacities, consumption of materials,utilisation of manpower, abnormal wastages inprocess/production and the reasons therefor, properutilisation of available financial resources, the deficienciesin the system of cost accounting currently followed,correctness of the cost computed, and the overall profitmade per unit. The reports a re also expected to discloseshortfalls in achievements against targets and thepersons/cost centres responsible for such shortfalls. Thus,the data available in the cost audit reports should createcost consciousness in the management, thereby leading tobetter efficiency, lower costs, higher profit and, possibly,in some cases a reduction in consumer prices. Theprogressive managements of the industries covered byCost Accounting (Record) Rules have already startedrecognising the usefulness of the statutory rules and havevoluntarily introduced continuous internal cost audit insome cases. From the information gathered it transpiresthat in the units where cost audit has been ordered andreordered by the Company Law Board, the second andsubsequent cost audit reports revealed improvements interms of better cost control and hence overallperformance [13]. It is to be hoped in the Indian contextthat, as the concept of cost audit gets into mainstreamindustry by the inclusion of more and more industrieswithin its scope, fruitful results will ensue . Th esedevelopments might possibly have prompted authoritiesin some other Asian countries (e.g. Bangladesh, Pakistan,Sri Lanka) to consider incorporating similar provisionsin their Companies Acts. However, it is likely that, asIndia becom es more open economically and privatisationgains momentum, the whole question may have to bere-examined. Much further research is also perhapsnecessary before further international recognition ofthe idea is accorded. At the root of the matter is thequestion of whether financial audit in its present form issufficient universally. The answer is inextricably tied tothe issue of mandatory audit for cost and managementaccounts.

-

8/2/2019 1990 Mandatory Audit for Cost and Management Accounts

7/7

16 MANAGERIAL AUDITING JOURNAL 5 ,3

ConclusionPresent worldwide practice is that statutory audit ismandatory only for the external wing of accounting:financial accounting and external reporting. In discussingthe idea of extending such mandatory audit to the internalwing, we have come to the conclusion that the idea, farfrom being pre posterou s, is infeetconceptually compelling.From a "systems-environment linkage" perspective, threepersuasive reaso ns can be advanced in support of the idea.First, differential treatment of the two wings of accountingleads t o an unw arranted and fallacious d ichotomisation ofthe "external" from the "internal" dimensions oforganisational reality. By polarising the (external) exchangemom ent and the (internal) transformation mom ent of theinput-transformation-output cycle, the dichotomy truncatesthe recursive circuit of capital, thereby ignoring theimportance of the relationship between efficiency andeffectiveness in organisational life. Secondly, the differentialtreatm ent ign ores the autopoietic nature of social systems.The inherent open-closed duality of autopoietic systemsimplies that the autonomy characterising the internalreproductive processes of organisational closure is justas crucially important as th e de penden ce that derives fromthe openness of a system to its external environment.Systems do not merely depend upon or react to theirenvironmental contingencies; they also actively participatein the creation of their future environments through whatare intrinsically self-referential activities. Finally, thedifferential treatment ignores the reflective-constitutivedialectic, whereby internal transformation processes mayand do have important, yet unintended, consequ ences forthe external.On the other hand, from an institutional standpoint,internal accounting for transformational activities is privyto the firm and hence potential disclosures, because ofmandatory audit and a regulatory strait-jacket, mayultimately prove to be detrimental to the very survival ofthe firm. Such a regulatory m easure may, in the long term ,seriously inhibit the entrepreneurial spirit, the veryfoundation of corporate business and economic growth anddevelopment. This institutional dilemma is well illustrated

by India's pioneering experiment. Not only has theGovernm ent of India had to move cautiously (and pe rhap seven hesitantly) by imposing regulatory measures onlyselectively; the experiences of the companies that haveundergone the experiment also reflect a mixed reactionabout the potential benefits from the experiment.References1. Oliga, J.C., "The Quantitative vs Behavioural Aspects ofManagement Accounting: Wings of Dichotomy orDialectic?", Proceedings (Supplementary) of the 31stAnnual Meeting of the International Society for GeneralSystems Research, Budapest, Hungary, 1987.

2. Voorhees, B., "Trialectical Critique of ConstructivistEpistemology", in Dillon J.A., Jr (Ed.), Mental Images,Values, and Reality, Society for General SystemsResearch, Louisville, Ky, 1986.

3. Colletti, L., "Marxism and the Dialectic", New LeftReview, Vol. 93, 1975.4. Gharajedaghi, J., "Social Dynamics: Dichotomy orDialectic?", in Ragade, R.K. (Ed.), General Systems,Society for General Systems Research, Louisville, Ky,1986.5. Fine, B. and H arris, L., Re-reading Capital, Macmillan,London, 1979.6. Maturana, H. and Varela, F., Autopoiesis and Cogn ition,D. Reidel, Boston, Mass., 1980.7. Varela, F., Autopoiesis: A Theory ofLiving Organization,Elsevier, New York, 1981.8. Zeleny, M. (Ed.), Autopoiesis, Dissipative Structures andSpontaneous Social Orders, Westview, Boulder, Colo.,1980.9. Bednarz, J., Jr, "Autopoiesis: The Organisational Closureof Social Systems", Systems Research, Vol. 5 No. 1,1988,pp. 57-64.10. Giddens, A., Th e Constitution of Society, Polity Press,Oxford, 1984.

11. Rao, A.V.S., Practising M embers' Meet, New Delhi, 1988.12. Chakrawarty, P., "Auditing Industrial Performance: India'sExperience", Managerial AuditingJournal, Vol. 2 No. 2,1987.13. Institute of Cost and Works Accountants of India (ICWAI),1986-87 AnnualReport;1987 Cost Audit: Social Objectives.

B.C. Ghosh and J.C. Oliga are at the Nanyang Technological Institute, Singapore; B. Banerjee works in the Universityof Calcutta, India.