172 Online

-

Upload

paulmazziotta -

Category

Documents

-

view

250 -

download

0

Transcript of 172 Online

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

1/85

FOCUS:

FEATURE:

PLUS:

FOCUS: Prevention & Clean-up of Unplanned Explosions

FEATURE: Asia & the Pacifc

PLUS: Notes from the Field and Research & Development

Issue 17.2 | Summer 2013

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

2/85

Te Journal o ERW and Mine ActionCenter or International Stabilization and Recovery

at James Madison UniversityIssue 17.2 Summer 2013 | ISSN: 2154-1469

Print Date: July 2013

Journal o Mine Action (printed edition)Issue 3.3 through Issue 12.1: ISSN 1533-9440

Te Journal o ERW and Mine Action (printed edition)Issue 12.2 and ongoing: ISSN 2154-1469

Journal o Mine Action (online edition): ISSN 1533-6905

he Journal o ERW and Mine Action (online edition): ISSN 2154-1485

Upcoming Issue

Issue 17.3 | Fall 2013 (Print and Online)Focus: Survivor AssistanceFeature: Te Middle EastSpecial Report: SyriaVisit http://cisr.jmu.edu/journal /cps.html or more details and additional Calls or Papers.

ON THE WEB: http://cisr.jmu.edu/Journal/17.2/index.htm

Te Journal of ERW and Mine Action is a professional trade journal for the humanitarianmine action and explosive remnants of war community. It is a forum for landmine andERW clearance best practices and methodologies, strategic planning, mine risk education

and survivor assistance.TeJournal o ERW and Mine Action Editorial Board reviews all articles or content andreadability, and it reserves the right to edit accepted articles or readability and space, andreject articles at will. Manuscripts and photos will not be returned unless requested.

Te views expressed in Te Journal o ERW and Mine Action are those o the authors and do nonecessarily reect the views o the Center or International Stabilization and Recovery, JameMadison University, the U.S. Department o State or the U.S. Army Human itarian DeminingProgram.

Authors who submit articles to Te Journalare expected to do so in good aith and are solelyresponsible or the content therein, including the accuracy o all inormation and correcattribution or quotations and citations.

Please note that all rights to content, including photographs, published in Te Journal arreserved. Notication and written approval are required beore another sou rce or publicationmay use the content. For more details please visit our website or contact the editor-in-chie.

Tao GrithsMartin JebensAtle KarlsenEdward LajoieNguy

~n Ti. Ty Nga

ed PatersonVicki Peaple

R&D Review BoardMichael BoldCharles Chichesterom HendersonPehr LodhammarNoel MullinerPeter NganErik olleson

CISR Programming andSupport StaffKen Rutherord, DirectorSuzanne Fiederlein, Associate DirectorKaylea Algire, Fiscal echnicianDaniel Baker, Research AssistantGeary Cox, Program ManagerCarolyn Firkin, Program Support echnicianEdward Lajoie, Assistant Program Manager

Cameron Macauley,rauma Rehabilitation Specialist

Nicole Neitzey, Grants OcerJohn Meagher, Research AssistantSusan Worrell, Fiscal echnician

CISR Program AssistantsRina Abd El RahmanBrandy HartEric KeeerPaige OberJessie RosatiChristopher SheehyKatie Stolp

Please direct all Journalsubmissions, queries and subscription/CFP requests to:

Lois Carter Craword, Editor-in-ChieCenter or International Stabilization & RecoveryJames Madison University800 S. Main Street, MSC 4902Harrisonburg, VA 22807 / USAel: +1 540 568 2503Fax: +1 540 568 8176Email: [email protected]

ContributorsMarian BechtelDaniel BraunEmanuela Elisa CepolinaMichael CreightonAnna CroweBonnie DochertyJo Durham

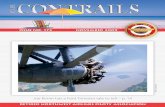

Cover PhotoQuality assurance for the Underwater UXO Clearance of Lake Ohrid, Republic of Macedonia, is conducted by PED

Sava d.o.o., Kranj, Republic of Slovenia. The project was funded by the Ofce of Weapons Removal and Abatemen

in the U.S. Department of States Bureau of Political-Militar y Affairs (PM/WRA) under the project management of IT

Enhancing Human Security and implementing partner Republic of Macedonia Protection and Rescue Directorat

(RMPRD). During three unexploded ordnance (UXO) clearance phases, RMPRD divers cleared more than 26,000 sq m

of Lake Ohrids bottom using underwater metal detectors and additional 30,000 sq m using visual detection. Altogethe

more than 19 tons of UXO were safely removed and destroyed.

Photo courtesy of Mr. Esad Humo, PED Sava d.o.o.

Mohammed QasimElena RiceKen RutherordAndy SmithAllen D. anBlake Williamson

To help save natural resources and protect our environment, this edition

of The Journal of ERW and Mine Actionwas printed on 30-percent post

consumer waste recycled paper using vegetable-based inks.

Like CISR on FACEBOOK at http://www.acebook.com/JMUCISR

Follow our blog on TUMBLR at http://cisrjmu.tumblr.com

Follow us on TWITTER at #cisrjmu

CISR Publications StaffLois Carter Craword, Editor-in-ChieAmy Crockett, Copy EditorHeather Holsinger,

Communications SpecialistJennier Risser, Managing EditorRachael ayanovskaya,

echnical & Content EditorBlake Williamson, Assistant Editor

Editorial BoardLindsay AldrichKatherine BakerLois Carter CrawordKristin DowleyJennier RisserKen RutherordRachael ayanovskaya

Editorial AssistantsDaniel BraunChloe CunninghamAlison DomonoskeBrenna FeiglesonPaul GentineMegan HintonEric KeeerPaige OberSarah PeacheyErica QuilliotineElisabeth ReitmanKathleen SensabaughDane SosnieckiJulie Anne Stern

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

3/85

Editorial

3 Director's Message

4 Abandoned Ordnance in Libya: Treats to Civilians andRecommended Responsesby Bonnie Docherty and Anna Crowe

Focus: Prevention & Clean-up o Unplanned Explosions

8 Weapons and Ammunition Security: Te Expanding Role oMine Actionby Elena Rice

Feature: Asia & the Pacifc

12 Cluster Munition Remnant Survey in Laos by Michael Creighton,Atle Karlsen and Mohammed Qasim

17 Assessment o Vietnams National Mine Action Programby ed Paterson and Tao Grifths

22 Securing Health Care Rights or Survivors: Developing an EvidenceBase to Inorm Policyby Jo Durham

26 Association or Empowerment o Persons with Disabilities in Quang BinhVietnam by Nguy~n Ti. Ty Nga

30 Mass Fitting or Amputees in am Kyby Ken Rutherord

Special Report: Underwater UXO Clearance & Detection

32 Addressing Underwater Ordnance Stockpiles in Cambodiaby Allen D. an

Notes rom the Field

38 Going Mobile: Inormation Sharing and the Changing Face oDigital Data Collection by Edward Lajoie

41 Making It Relevant: Risk Education in DRCby Vicki Peaple

44 Land Release in Action by Emanuela Elisa Cepolinawith editorial support rom Andy Smith

Research and Development

52 A Stand-o Seismo-acoustic Method or Humanitarian Deminingby Marian Bechtel

57 Analyzing Functionality o Landmines and Clearance Depth as a ool toDefne Clearance Methodologyby Martin Jebens

Endnotes 64

Access a PDF or html version o The Journal of Mine Action,

Issue 17.2 with bonus online content, and all past issues o

The Journal at http://cisr.jmu.edu.

Dear Readers,

Tis issue oTe Journalcovers a wide variety o interesting andtimely explosive remnants o war (ERW) and mine action topics, in-cluding unplanned explosions and weapons security, underwaterclearance, survivors rights aecting Asia and the Pacic, and re-search and development studies.

For example, in an article by Elena Rice o the U.N. Mine ActionService, the author contends the mission o the mine action commu-nity must expand to include weapons and ammunition security. Dis-cussing victim assistance and disability rights o survivors in Asia

and the Pacic, Jo Durham (University o Queensland) emphasizesthe importance o securing health care rights or survivors in Cam-bodia, Laos and Vietnam, while Nguyn T Ty Nga reects on howthe Association or the Empowerment o Persons with Disabilities,which employs ERW and mine survivors as outreach workers in Viet-nam, successully helps survivors reintegrate into their communities.Allen an o Golden West Humanitarian Foundation discusses thethreat o contamination rom sunken watercra littering Cambodiasrivers and tributaries, and how Golden West is addressing the prob-lem by identiying and training suitable candidates or underwatertraining. In addition, the online edition oTe Journalhas additionalarticles, and we suggest you access our current issue online.

Besides producing this publication, the Center or InternationalStabilization and Recovery (CISR) is busy providing programs and

training at James Madison University and abroad. For instance, CISRrecently wrapped up our ninth Senior Managers Course in ERW andMine Action (SMC). Currently supported by the U.S. Department oState, the SMC provides mine action program managers an innova-tive and challenging curriculum covering a broad range o topics toimprove par ticipants management ski llsrom conventional weap-ons destruction, victim assistance, physical security and stockpilemanagement to strategic management, public relations and emergingtrends in the post-conict recovery arena. Tis year we had the hon-or o hosting 14 participants rom 13 countries, bringing our total tomore than 270 participants rom 46 countries, including the mine ac-tion and ERW sessions we conducted in Jordan and Peru. We plan tocontinue with the SMC program next year (check the CISR website inwinter 2013 or application details).

We are continuing our work with peer-to-peer support programsin Burundi and are moving into new areas o program management,including advocating or the rights o persons with disabilities inVietnam and providing mine risk education to Syrian reugees inthe Middle East.

As we share our lessons learned in uture issues o Te Journal,we encourage you to send us articles detailing your best practicesand lessons learned as well. Our all issue oTe Journalis an excit-ing one, ocusing on survivor assistance, a long with current conictsand the evolving landmine/ERW situations in the Middle East, in-cluding Syria. We look orward to hearing rom you.Sincerely,

Ken Rutherord

Directors Message

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

4/854 editorial | the journal o ERW and mine action | summer 2013 | 17.2

EDITORIAL Abandoned Ordnance in Libya:

Threats to Civilians and

Recommended ResponsesIn a report released in August 2012, Explosive Situation: Qaddas Abandoned Weapons and the

Threat to Libyas Civilians, researchers rom Harvard Law Schools International Human Rights

Clinic (IHRC) examined Libyas abandoned ordnance problem and its humanitarian consequences

or the local population.1,2 Based on eld and desk research, the report documents the threats these

weapons pose, analyzes steps to address them and oers recommendations to minimize civilian

harm. IHRC co-published the report with the Center or Civilians in Confict (ormerly CIVIC) and the

Center or American Progress. In this article, two o the reports authors summarize its 2012 nd-

ings and recommendations.

by Bonnie Docherty and Anna Crowe [ Harvard Law School ]

Vast quantities o abandoned ordnance have littered

Libya since the end o the 2011 armed conict. 3,4 Mu-

nitions, ranging rom bullets and mortars to torpe-

does and surace-to-air missiles, have been scattered around

inadequately guarded bunkers; local militias have gathered

stockpiles in urban areas; and individual civilians have col-lected weapons or scrap metal or souvenirs. Determining the

scale o the problem is dicult, as Moammar Gadhas regime

acquired an arsenal worth billions o U.S. dollars. 2 Moreover,

the regimes weapons were divided among dozens o ammuni-

tion storage areas, each containing 25140 bunkers.5

Many experts express concern over the international pro-

lieration o these weapons, but the abandoned ordnance has

also posed serious domestic threats to civilians. Te report

Explosive Situation: Qaddas Abandoned Weapons and the

Treat to Libyas Civilians documents these dangers and ex-

amines the key activities needed to minimize them: stockpilemanagement, clearance, risk education and victim assistance.

As a oundational step, the Libyan government should create

a coordinated and comprehensive national plan eliminating

the government conusion generated by competing agencies

and acilitating the our areas o work.5 In addition, the inter-

national community needs to provide ongoing and increased

assistance and cooperation. Te prevention o more civilian

casualties requires urgent and immediate eorts by national

and international entities.

Threats to Libyas Civilians

During its eld mission to Libya, Harvard Law Schools

International Human Rights Clinic (IHRC) documented

ve major threats that abandoned ordnance has posed to

civilians.6 Each o them has the potential to lead to additional

civilian casualties.7

Stockpile locations. Te positioning o stockpiles in popu-

lated areas coupled with poor management practices have in-

creased the risk o catastrophic explosions that would cause

signicant injury and death. In March 2012 a member o the

Military Council o Misrata, where this practice has been par-

ticularly common, estimated that in his city more than 200

militias each held between six and 40 shipping containers ul l

o weapons.8 In the same month, an explosion in Daniya, a

town 20 km (12 mi) rom Misrata, exemplied the danger. A

militia had stored weapons in 22 adjacent shipping contain-

ers, and a stray shot reportedly penetrated one o the con-tainers, detonating the ammunition in a chain reaction and

spreading explosive remnants o war (ERW) across the neigh-

borhood. A mine rom the blast later killed a DanChurchAid

deminer, and in late March the community was again using

buildings in the aected area.9,10

Curiosity. Inquisitiveness has urther endangered civil-

ians who visit contaminated sites or handle abandoned weap-

ons. Children are particularly curious and unsuspecting, and

they have oen played with munitions. A Danish Demining

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

5/8517.2 | summer 2013 | the journal o ERW and mine action | editorial

Group manager observed that children try to set o the anti-

aircra missiles with nails and bricks, and IHRC learned o

multiple casualties resulting rom such behavior.11

Harvesting weapons materials. Civilians have been killed

or injured while harvesting scrap metal to sell or explosives

to use or shing. For example, a man and his two sons died

during an explosion in the Zintan ammunition storage areawhile gathering scrap metal in December 2011. Te mans

amily later asked a MAG (Mines Advisory Group) deminer

to clear piles o collected metal and propellant rom the am-

ilys home.12

Community clearance. Since the conict, abandoned and

unexploded ordnance has contaminated homes, public build-

ings (such as schools and mosques) and armland. Eager to

make their communities saer, some civilians have tried clear-

ing areas without expert training or assistance, an activity

that endangers them and exacerbates the challenges o pro-

essional clearance.Displays o mementos. Finally, war museums and pri-

vate individua ls have put weapons on display. Te museum

in Misrata, located on the citys main street, has exhibited

a large collection o weapons in a relatively haphazard way.

Demining organizations have worked to make such muse-

ums sae; however, the museums have undermined risk edu-

cation eorts by normalizing the collection o weapons and

subsequently encouraging private displays, which deminers

cannot monitor.

Stockpile Management

Since the end o the 2011 armed conict, proper stockpile

management has been sorely lacking in Libya, but good prac-

tices are essential to minimizing the threats o abandoned

ordnance to the Libyan people.13,14 International organizations

and the national governments Libyan Mine Action Center

(LMAC) have worked together to conduct surveys, and some

local authorities have agreed to measures to improve prac-

tices.15,16,17 Progress has been limited, however. Unstable and

inadequately secured weapons have remained in bombed am-

munition storage areas, temporary storage acilities and mili-

tia shipping containers.

Poor stockpile management practices have abounded. Max

Dyck, the ormer U.N. Mine Action Service (UNMAS) pro-

gram manager in Libya, reported in July 2012 that ammuni-

tion storage areas, littered with munitions that were kicked

out o bunkers by NAO bombings, had no real security. 5 As

a result, civilians have had access to the weapons. Further-

more, local militias have used dangerous storage methods,

such as keeping dierent types o ammunition together and

placing stockpiles within populated areas. A reluctance to give

up weapons acquired during the armed conict has interered

with U.N. and nongovernmental organization (NGO) eorts

to improve management practices and destroy unstable weap-

ons. In addition, unding or stockpile management initiat ives

has been insucient, and coordination within the nation-

al government, between national and local government, and

among the militias has been inadequate.

As a sovereign state, Libya bears the primary responsibil-

ity or dealing with its stockpiles. W hile it is engaged in a time

o political transition and has many pressing concerns, Libya

Weapons ranging rom artillery shells to surace-to-air mis-

siles spill out o an ammunition bunker near Zintan that wasbombed by NATO in 2011. These unstable and inadequatelysecured weapons exempliy the danger posed to civilians by

Moammar Gadhas abandoned ordnance months ater the

end o the armed confict.Photo courtesy of Nicolette Boehland.

Curious locals explore a tank yard in downtown Misrata where an Egy

tian migrant was gathering scrap metal. Many civilians have been killeor injured while harvesting scrap metal or explosives rom weapons.Photo courtesy of Bonnie Docherty.

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

6/856 editorial | the journal o ERW and mine action | summer 2013 | 17.2

should develop the national plan discussed above. In addi-

tion, it should take specic steps to reduce the humanitarian

threats caused by poor stockpile management. For example,

Libya should do the ollowing:

Allocate more resources to improving

stockpile practices

Increase physical security at ammunition storage areas

Prioritize coordination with militias to

move stockpiles out o populated areas

Initiate a program or building technical expertise

within Libya

Request international assistance to help put these

steps in place

Remedial Measures: Clearance, Risk Education

and Victim Assistance

o maximize civilian protection, a trio o remedial

measuresclearance, risk education and victim assistanceshould complement improvements in stockpile management.

Aer the conict, UNMAS and international NGOs took

the lead on clearance eorts.18 Tese groups, however, have

not received support rom the Libyan government, have not

had enough explosives to undertake controlled demolitions,

have had diculty nding sta with technical expertise and

sometimes have aced obstacles when accessing sites. Groups

have also expressed concerns about the lack o local capacity

to take over uture clearance activities.

International NGOs have played a role in risk education

and worked closely with local risk educators. Tey have held

sessions raising awareness o the dangers o abandoned ord-

nance and other ERW, distributed brochures, set up regional

ERW-inormation hotlines, placed billboards on streets and

created radio messages.19,20 Handicap International and MAG

told the IHRC team that they have also cooperated with the

Ministry o Education to train school teachers to provide risk

education.21 Tese NGOs have received some additional as-

sistance rom LMAC (part o the Army Chie o Sta s oce)

and the Libyan Civil Deense.17,22

Risk educators have aced several challenges, including

dangerous attitudes toward weapons, particularly among

children; diculties in reaching inuential audiences (espe-

cially women, who play a key role in educating their amilies

about ERW risks); insucient unding and the need to in-

crease capacity in Libyan civil society to undertake urtherrisk education activities.

As o July 2012, Libya had no established assistance pro-

gram dedicated to the victims o abandoned weapons and

other ERW. However, the broader assistance program or war

vict ims, which is run through t he Libyan Ministry o Health,

has helped those harmed by ERW.23

Libya, as the aected country, bears primary responsibility

or these remedial measures. In addition to developing a na-

tional plan, it should do the ollowing:

Increase its al location o resources

Promote capacity building and assist with the growth olocal civil society

Help deminers obtain explosives or ERW destruction

and acilitate access to contaminated sites or clearance

Ensure its victim assistance program ollows inter-

national standards articulated in the Plan o Action

on Victim Assistance under Protocol V on ERW to

the Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the

Use o Certain Conventional Weapons Which May Be

Deemed to Be Excessively Injurious or to Have Indis-

criminate Eects24

International Cooperation

and Assistance

Te our areas discussed previouslystockpile manage-

ment, clearance, risk education and victim assistancerequire

signicant resources and expertise, so international coopera-

tion and assistance is critical to protecting civilians rom the

threat o these weapons.

As o July 2012, the international community had provid-

ed more than US$20 million to address ERW in Libya, but

A visitor looks at the weapons on display at a war museumlocated on the main street in Misrata. Civilians may interpret

such public displays o munitions to mean it is sae to bringweapons into their homes.Photo courtesy of Anna Crowe.

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

7/8517.2 | summer 2013 | the journal o ERW and mine action | editorial

Anna Crowe completed a Master o

Laws at Harvard Law S chool in 2012.

Her academic interests lie in interna-

tional human rights law and interna-

tional humanitarian law. She works in

Bogot, Colombia, as a Henigson Fel-

low rom Harvard Law School. She

previously worked as a clerk to the

chie justice o New Zealand and as

a New Zealand government lawyer.

Anne Crowe

Human Rights Program,

Harvard Law School

Tel: +57 320 2720 163

Email: [email protected]

that assistance was decreasing while the

threats to civilians remained.25,26,27 o

address the situation adequately, Libya

needs increased and ongoing assistance.

During the conict, NAO launched

an estimated 440 airstrikes on ammu-

nition bunkers. Rehabilitating a sin-

gle bombed-out bunker can cost more

than US$1 million, not including secu-

rity walls, ences and lights, or clearance

o the ordnance scattered in the attack. 5

While nancial contributions are valu-

able, assistance can also come in the

orm o material or technical support.

As a result, all states, even those with

a limited ability to give nancial assis-

tance, should be in a position to provide

some kind o assistance.

NAO and its member states should

accept special responsibility to provide

cooperation and assistance to address

the abandoned ordnance problem re-

lated to bombed ammunition bunkers.

Although lawul, NAO airstrikes on

the bunkers contributed to the ERW

situation. NAO assistance would be

consistent with the emerging princi-

ple o making amends, under whicha warring party provides assistance to

Bonnie Docherty is a senior clinical in-

structor and lecturer on law at Harvard

Law Schools International Human

Rights Clinic (IHRC).She has extensive

experience doing eld investigations on

the eects o armed confict and spe-

cic weapons systems on civilians. She

was actively involved in the negotiations

o the Convention on Cluster Munitions

and has conducted in-depth legal

work promoting its implementation.

Bonnie Docherty

Human Rights Program

Harvard Law School

6 Everett Street, 3rd Floor

Cambridge, MA 02138 / USA

Tel: +1 617 496 7375,

Email: [email protected]

A shipping container that was part o a militia's urban stockpile exploded inMarch 2012, setting o a chain reaction that littered a Daniya neighborhood

with weapons. The painted message at the site reads, Dont come closer

danger, death.Photo courtesy of Nicolette Boehland.

civilians harmed in the course o law-

ul combat operations. Finally, such

assistance would be consistent with

the mandate under which NAO in-

tervened in Libyas armed conict: the

protection o civilians.

Conclusion

Due to the scale o Libyas aban-

doned ordnance situation, solving the

problem is a monumental task. Te

weapons have already killed or injured

civilians , and more casualties are almost

guaranteed. Libya and the international

community must thereore urgently de-

velop a coordinated response seeking to

minimize this humanitarian threat. As

a member o Libyan civil society told

IHRC, the country needs more cooper-

ation between all partiesall the way

rom NAO to the man who lives next

to the abandoned ordnance.28 I suc-

cessul, such coordinated action could

not only reduce the loss o lie in Libya,

but also serve as a model or dealing

with abandoned ordnance in other post-

conict situations.

See endnotes page 64

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

8/858 ocus | the journal o ERW and mine action | summer 2013 | 17.2

F

OCUS Weapons and Ammunition Security:

The Expanding Role o Mine Action

by Elena Rice [ United Nations Mine Action Service ]

Signicant expertise is necessary to meet the security challenges posed by unsecured and poorly

stored weapons and ammunition. To address this threat, many donors and mine action actors, in-

cluding the United Nations Mine Action Service, are including weapons and ammunition security

management as a core role.

OOn 27 November 1944, an underground bunker

holding 4,000 tons o ordnance detonated at the

Royal Air Force Fauld underground munitions

depot in Staordshire, England. Te explosion was the larg-

est non-nuclear explosion ever recorded, leaving behind the

Hanbury Crater (120 m deep [394 ] and 1.2 km [1,312 yd]

wide). While the exact death toll is unknown, approximately

70 people died.1 ime and time again, accidental explosions

at ammunition storage acilities have caused death and de-

struct ion. For example, in Nigeria in 2002 an armory ex-

plosion claimed 1,100 lives. In 2012 in the Republic o the

Congo (ROC) 282 people were killed, and children at a near-

by school were spared only because the explosion occurred

on a weekend.2

Te human tragedy o these events highlights the impor-

tance o preventive measures against unplanned explosions.

The inside o a damaged ammunition bunker.Photo courtesy of the author.

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

9/8517.2 | summer 2013 | the journal o ERW and mine action | ocus

However, the immediate impact is compounded by what is

arguably a more widely catastrophic byproduct o improp-

erly stored stocks. Te medium- to long-term security threat

posed by unsecured munitions holds exponentially more dan-gerous potential or destabilizing countries and regions, with

serious implications or international peace and security.

Prolieration o weapons and ammunition during and

in the atermath o recent conlicts starkly reveals the

dangers o unsecured arms and ammunition. As Moammar

Gadhais government gradually lost control over Libya

in 2011, opposition orces and other groups gained access

to unsecured depots. Looted weapons have since been

traced to Gaza, Somalia, and West and North Arica. he

U.N. Security Council stated in December 2012 that the

continued prolieration o weapons rom withi n and outside

[the Sahel] threatens the stability o states in the region.3

Weapons prolieration uels insurgency, with the 20122013

crisis in Mali clearly demonstrating the impact o poorly

stored and easily accessible weapons.

Stockpile Security

With the U.N. General Assembly calling or practical

measures to mitigate this threat, the international communi-

ty increasingly recognizes the challenge and calls upon states

to make realistic assessments o the potential security risks

o their stockpiles, while appealing to states in a position to

do so to assist those with less developed capacity. 4,5 Ensuring

the physical security o storage acilities reduces the possibil-ity that these weapons will be removed and used or nearious

purposes, including as components o improvised explosive

devices. Te role o the mine action community in alleviating

this risk is apparent and the need to ocus resources into practi-

cal implementation in the eld is increasingly recognized.

Te United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) in-

volvement in weapons and ammunition security management

draws upon its ability to contribute expert skills, specialized

equipment, and experience with explosive hazards. Several

UNMAS-implemented projects ocus on securing weap-

ons and ammunition rst and storing the materials second,emphasizing simple preventive measures such as perimeter

encing around ormal and inormal storage areas. For in-

stance, with the program in Misrata, Libya, UNMAS placed

secure storage containers inside the existing ammunition

storage areas (ASA), which were too large to secure quickly.

Implementing nongovernmental organizations (NGO) con-

ducted clearance inside the ASA to provide space, then add-

ed encing to increase security around the portion o the ASA

that was cleared. While extensive damage has already been

A damaged ammunition bunker in Libya.Photo courtesy of author.

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

10/850 ocus | the journal o ERW and mine action | summer 2013 | 17.2

done in terms o weapons prolieration rom Libya to region-

al conicts, these measures, implemented at the local and

national levels, address the ongoing threat in the context o

Libyas eorts to restore public secur ity.

Te U.N. program in Cote d Ivoire represents a pivotal suc-

cess or mine action-driven implementation o weapons and

ammunition management. Te HALO rust (HALO), with

UNMAS coordination, worked with Ivorian security orces

to rehabilitate a majority o the countrys storage acilities.

National technical capacity was strengthened to such an ex-

tent that the state became a regional model or sae and se-cure ammunition storage and is increasingly called upon to

share experience and technical expertise. In a strong display

o SouthSouth cooperation, Chad, the Democratic Republic

o the Congo (DRC) and the ROC v isited Cote d Ivoire in 2012

to learn rom its experience and apply the countrys methods

in the implementation o their own national weapons and am-

munition management operations.6

UNMAS made strong headway in accessing peacekeep-

ing and political unds or weapons and ammunition man-

agement, successully advocating to the U.N. Department o

Peacekeeping Operations and U.N. Department o Political

Aairs that unsecured munitions threaten security and sta-

bility and uel terrorist activities. As a result, the U.N. mis-

sions in Cote dIvoire, DRC, Libya and South Sudan have

allocated specic unding to UNMAS or projects that ad-

dress security and storage. UNMAS has in turn coordinat-

ed and implemented these activities through NGOs, such as

HALO, MAG (Mines Advisory Group) and t he Swedish Civil

Contingencies Agency. As circumstances demonstrate the ne-

cessity or similar projects in Mali and other conict-aected

countries, the trend o including weapons and ammunition

security management unding in peacekeeping budgets will

likely continue.

The Expanding Role o Mine Action

he term mine action implies that the work ocuses sole-

ly on landmines . Many states a nd NGOs have long advocat-

ed that explosive remnants o war (ERW) and small arms/

light weapons (SA/LW) need to be looked at in un ison. For

Libyan stockpile with artillery shells and a man-portable air-deense system (MANPADS).Photo courtesy of Nathan Beriro.

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

11/8517.2 | summer 2013 | the journal o ERW and mine action | ocus

example, the U.S. Department o State

initiated a comprehensive approach

to conventional weapons destruction

(CWD) incorporating mines, ERW

and SA/LW, as well as physical securi-

ty and stockpile management (PSSM)

with the consolidation o s everal relat-

ed oices into the Oice o Weapons

Removal and Abatement in 2003; other

states have also adopted t his approach.

An important step in educating

the disarmament-ocused diplomat-

ic community was the participation

o UNMAS and several mine action

NGOs, including MAG and Handicap

International, in the Programme o

Action on SA/LW in September 2012.

1

For instance, UNMAS presented a side

event at the conerence: Preventing

big bangs and saving lives ocused on

UNMAS work in Cote dIvoire and

Libya. Practical implementation les-

sons: armory and stockpile assessment

in Arica was organized by the U.K.s

Foreign and Commonwealth Oce and

MAG. Tese eorts represent progress

in encouraging member states to adopt

an expanded mine action role. However,more remains to be done beore the mine

action community is recognized as a key

implementer, supporting the weapons

and ammunition management agenda.

All mine action actors are responsible

or lobbying, advocacy and re-branding

their wide range o work (to include all

mine action, CWD, PSSM, SA/LW and

weapons security issues) as critical or

both security and development.

Second, sucient and sustainedunding is essential to the predictability

and eectiveness o interventions; how-

ever, gaining access to unds remains a

challenge or those implementing mine

action. Mine action implementers must

continue to engage in outreach eorts,

establish new links with these entities

and lobby states likely to und projects

in aected states.

Mine action work has traditionally

been unded through a dedicated gov-

ernmental department or mine action

or by oces dealing with humanitar-

ian unding. Meanwhile resources or

weapons and ammunition management

projects are requently derived rom di-

erent departments ocusing on disar-

mament, nonprolieration, security and

stabilization. Clear exceptions exist, or

example the U.S. State Department has

consolidated CWD and PSSM und-

ing in one combined budget. Likewise

U.K.s Department or International De-

velopment has generously unded arms

and ammunition management along-

side conventional mine action in com-

bined projects. We hope that this trend

will continue.

By securing weapons and ammuni-

tion, the mine action community can

prevent their prolieration and misuse

by nonstate actors. Tis role or mine ac-

tion is becoming increasingly recog-

nized by U.N. member states. However,

more work remains, including accessing

new resource pools and expanding or

re-branding the mine action mission tocorrespond with the widening spectrum

o its activities. UNMAS stands ready to

assist with these eorts.

See endnotes page 64

Te views expressed in this article are

those o the author and do not necessarily

represent the views o the United Nations.

Elena Rice began her mine action ca-

reer in 2006 with the United Nations

Mine Action Service (UNMAS) in South

Sudan. She has worked or UNMAS in

Aghanistan and in Gaza in the ater-

math o Operation Cast Lead. Currently,

she works in New York as special ad-

viser to the UNMAS director. Originally

rom Belast, Northern Ireland, Rice

holds two masters degrees rom the

University o Edinburgh in the U.K.

Elena Rice

Special Adviser to the Director

United Nations Mine Action Service

DC1, 760 U.N. Plaza

New York, NY 10017 / USATel: + 212 963 6975

Email: [email protected]

Skype: elena.rice

Website: www.mineaction.org

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

12/85eature | the journal o ERW and mine action | summer 2013 | 17.2

Cluster Munition Remnant Surveyin Laos

As the most heavily bombed country per capita in the world, clearance o cluster munition remnants

is a long and ongoing process in Laos. Norwegian Peoples Aid developed survey methodology to

address the unique challenges posed by cluster munition contamination.

by Michael Creighton, Atle Karlsen and Mohammed Qasim [ Nor wegian Peoples Aid ]

he clearance community traditionally uses struc-

tured surveys to locate and evaluate the extent o

contamination rom cluster munitions and explosive

remnants o war (ERW). However, Norwegian Peoples Aids(NPA) involvement in Southeast Asia over the last ew years

suggests current practices should be analyzed or eective-

ness and subsequently updated. raditional practices ocus

on battle area clearance and all types o unexploded ordnance

(UXO). In Cambodia, Laos a nd Vietnam, NPA ocuses on the

more commonly occuring cluster munition remnants (CMR)

in its method or UXO clearance. However, NPAs method still

considers and incorporates ecient ways to detect other UXO

and ERW.

When trying to dene the extent o the

problem with surveys, CMR present a dierent

challenge than landmines. CMR have uniquecharacteristics, which dier rom other types

o UXO and landmines.1,2 For instance, due to

the lack o extensive ground warare in Laos,

the incidence o considerable ragmentation

aecting detector use is inrequent and man-

ageable. CMR also all into more identiable

patterns than other UXO due to the deploy-

ment method. Tese patterns can be searched

or during echnical Survey (S). Additional ly,

CMR have a relatively high ailure rate, making

the pattern o deployment identiable in waysthat mines are not.

Te duration o CMR contamination can

also aect a traditional surveys ability to dene

the problem. Recent cluster munition strikes

may provide clear ootprints that can be sur-

veyed rapid ly and tasked or clearance, whereas

assessing the location and extent o contamina-

tion or older strikes is more challenging. Changes in the veg-

etation and landscape, deterioration o CMR and intererence

rom local populations, such as villagers completing partial

demining eorts, oen make the location and extent o con-tamination dicult to assess. Tis presents survey and clear-

ance organizations with the challenge o identiying where to

start and stop clearance.

For survey and clearance organizations using clearance re-

quests rom the local population as the only element o sur-

vey in their operational land release systems, the chal lenge

o when to start and stop is not oen adequately addressed.

While the inormation the local population provides orms a

large part o Non-technical Survey (NS) and S eorts, it

Figure 1. Surveyors move through a box beyond the initial evidence point.All graphics courtesy of the author.

FE

ATURE

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

13/8517.2 | summer 2013 | the journal o ERW and mine action | eature

should not determine conrmed hazardous areas (CHA) or

where to employ clearance assets.3 Survey decisions based

solely on requests rom the local population typically involve

extremely large areas that sometimes encompass entire vil-

lages. Recording a suspected hazardous area (SHA) or CHA

is not acceptable unless the area has a proven, valid claim o

contamination. Clearing an unconrmed area as i it is a CHA

wastes signicant time, unding and eort. In contrast to the

advances made in mine act ion over the last decade, many con-

taminated countries rely on civilian inormers to relay loca-

tions and the ex tent o contamination. However, CMR require

a more proessional, rigorous approach.

A New Approach

Demining organizations need to compile data gathered

rom the local population into a more thorough and proes-

sional NS and S system, using local inormation as well as

other indicators and survey methods to determine how best

to clear CMR. In the case o cluster munitions, their specic

types and methods o deployment can be used to develop oth-

er methodologies or NS and S approaches.

CMR have contaminated Laos or almost 50 years. Pro-

longed exposure to weather causes CMR to become in-

creasingly volatile, which makes determining the extent o

contamination dicult. Due to high levels o contamination,

CMR evidence is prevalent throughout most o the coun-

try; however, determining the extent o each area o con-

tamination is dicult. Tis uncertainty prohibits deminers

rom ocusing clearance assets in the contaminated areas. By

sourcing local inormation, NS can determine where survey

eorts should begin. Tese start or evidence points are iden-

tied and used to target the S, which then determines the

extent o the contamination in that area and creates a CHA.

Te CHA is reported to the national authority or addition to

the national contamination database (in the case o Laos, the

National Regulatory Authority or NRA).

Because determining where to start may be more manage-

able than determining where to stop or where to deploy clear-

ance assets, NPA developed the CMR survey methodology in

Laos to address the latter two issues.

Background Inormation

NPA ound that evidence points may be more dicult

to identiy in countries with contamination similar to Laos,

where contamination may be disturbed or partially exposed

(e.g., some areas o Vietnam). In these cases, the existence o

veried CMR in an area, determ ined through NS, may be

used as the start point or the S eort.

Due to the lack o extensive ground warare in Laos, bat-

tle areas requiring area clearance on the surace or at shallow

depths are rare, and spot tasks are sucient to destroy individu-

al pieces o ordnance. However, there are vast areas where large

bombs reside deep underground, and these are usually not en-

countered unless a particular development project requires deep

excavation.4

I an area experiencedground warare and received extensive

contamination, a CHA may be creat-

ed relative to the extent o the visible

contamination. Tis is rare in Laos, as

most contamination near the surace

usually consists o cluster munitions

and should be addressed through di-

erent methodologies.

Technical Survey

o address CMR contaminat ion inthe most ecient way possible, NPA

developed a system o S that takes

into account the unique characteris-

tics o cluster munitions contamina-

tion in Southeast Asia, including the

high metal signature o cluster muni-

tions (i.e., ootprint) and the ability

to walk with relative saety through

a suspected area. NPA uses a rapid

Bomblet found:

Stop / Record / Move to next box

Bomblet fragment(s) found:

Carry on survey / record if nothing else is found

Nothing found, after 20-30 minutes

Move on

UXO (not CMR) found:

Record for spot tasking & carry

on survey

Meaning

Bomblet gured by CMRs

Bomblet fragments found by CMRs

Nothing found by CMRs

Other UXO found by CMRs

Not surveyed inaccessibility

Not surveyed

ColorName

Red

Yellow

Green

Blue

Gray

Blank

CMRs

Figure 2. Team leader with GPS reading.

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

14/85eature | the journal o ERW and mine action | summer 2013 | 17.2

survey technique to eectively determine the extent o the

contamination beore clearance assets are employed.

In this process, the initial non-technical phase o the land

release process is conducted through village meetings and re-

view o existing documentation. Instead o identiying SHAs,

the NS records evidence points or both CMR and other

UXO in the area. All evidence points identied in a given area

(e.g., within the boundary o a village) are assigned to UXO

spot task teams, while CMR evidence points are addressed by

CMR survey teams.

Once the CMR survey (i.e., the S phase o the land release

process) is complete, a CHA polygon is ormed around the

contamination evidence and reported to the NRA as a CHA.

When clearing a CMR-surveyed site, in addition to clear-

ing the CHA, a 50 m (54 yd) ade-out area, the agreed dis-

tance rom a specic evidence point where the S/clearance

is carried out, is adopted rom the outer-most bomblets ound

within the CHA polygon.4

Te area cleared within the poly-gon, which includes any cleared, ade-out areas that extended

outside o the polygon, is classied as released ground. Te

rest o the area surveyed during the CMR survey, while deter-

mining the CHA, is classied as area surveyed only. Tis area

is not released as there was never a conrmed claim o con-

tamination rom which to release it.

Notably, to release land, there must have been an actual

conrmed claim o contamination. As a means o surveying

an area, visual observation cannot conrm contamination or

release land. Likewise, an area determined by a request-based

system should be considered a SHA and not a CHA. Te SHA

can be cancelled; when the actual contamination within the

SHA has been determined through S, it would then become

a CHA. In the CMR survey methodology a SHA is not creat-

ed, as it would be articial. Te S process commences rom a

conrmed evidence point, and a CHA is created through the

S activity.

CMR Survey

Te CMR survey methodology is based on existing

evidence (e.g., a bomblet or a valid claim o contamination)

and involves rapidly surveying 2,500 sq m (2,990 sq yd) boxed

areas or boxes beyond the initial evidence point. CMR survey

determines which boxes contain evidence o contamination.

Five surveyors are assigned to each box, and they use UXO

detectors (e.g., Vallon VMXC1-3) set to maximum sensitiv ity.

Te surveyors move through the box in a systematic manner,

under the direction o the section commander. I extensive

metal contamination is encountered in any area, the area

is skipped and the survey moves to an adjacent area. Te

purpose o the CMR survey is to paint a general picture o the

contamination in the area, with which surveyors can create

a CHA.

I surveyors nd a bomblet, survey in that boxed area is

terminated and the box is recorded in red. I the surveyors

nd ragments o CMR (e.g., a ragmentation ball rom a BLU

8 2 8 4868 88

9 29 49 69 89 109 129 149

7 27 47 67 87 107 127 147

6 26 46 66 86 106 126 149

5 25 45 65 85 105 125 145

4 24 44 64 84 104 124 144

3 23 43 63 83 103 123 143

108 128 148

BLU26

BLU26BLU26

BLU26BLU26

BLU26BLU26

BLU26 BLU26 BLU26 BLU26BLU26

BLU26

BLU26BLU26BLU26

BLU26

BLU26

BLU26

BLU26

BLU26

BLU26

BLU26

BLU26BLU26

40mm Rifle Grenade

BLU26

BLU26SboxName SearchDate Finding Result

A09

A10

A026

A027

A028

A029

A030

A044

A045

A046

A049

A050

A069

A070

A083

A084

A089

A090

A0104

A0109

A0123

A0124

A0129

A03

A07 11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

11-Aug-2011

12-Aug-2011

BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26 = 2

BLU 26 Fragment

Nothing Found

Nothing Found

Nothing Found

Nothing Found

Nothing Found

Nothing Found

Nothing Found

Nothing Found

Nothing Found

Nothing Found

Nothing Found

Nothing Found

Nothing Found

Nothing Found

Nothing Found

Could not be surveyed

Could not be surveyed

6

2

2

2

6

6

6

2

2

2

2

4

2

6

2

1

2

6

2

2

2

1

2

6

2

Figure 3. CHA establishment.

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

15/8517.2 | summer 2013 | the journal o ERW and mine action | eature

pecially signicant in Southeast Asia, where the vegetation is

a dominant limiting actor in any mine or UXO operation.

Te CMR survey methodology works eciently in average

levels o vegetation and only requires the ability o the de-

tector head to be pushed through and around vegetation. In

most cases, only minimal vegetation removal is needed or the

CMR survey methodology to operate.

Conclusion

Developed by NPA, the CMR survey approach in Laos

commenced in 2010 and the methodology was ully accept-

ed in mid-2012. As the CMR survey process involves prelimi-

nary survey, suspected areas can be conrmed and recorded

prior to targeted clearance, eliminating costly clearance o un-

contaminated land. Tis process provides a clear estimation

o clearance needs, and enables Laos to make more specic

and accurate assessments o needed assets and donor unding.

Tis requirement is dicult to achieve i survey/clearance or-

ganizations accept tasks based only on community requests,

where the extent o contamination is unknown until clearance

has been completed. Beore the use o CMR survey, alternate

surveys have resulted in expensive, superuous searches that

spent unnecessary assets without nding contamination.

26), the box is recorded in yellow. In yellow areas, sur veys are

continued until either a bomblet is ound or surveyors exceed

a timed limit o 2025 minutes. In this event, the recorded box

remains yellow. I no CMR evidence is ound within the box

during the allotted t ime, the box is recorded as green. Inacces-

sible boxes are recorded in gray, and boxes that contain other

UXO are recorded in blue. While the CMR survey is ocused

on identiying the CHA o CMR contamination during the S

phase, all other UXO in the area are recorded during the NS

and are destroyed by UXO teams during the clearance phase

o the land release process.

Five deminers and a section commander spend a maxi-

mum o 20 to 25 minutes in each boxed area. Tis includes

the time to lay out the dimensions o the box, which is donerapidly with a rope system. An assessment during the trials

showed that this time rame allows the group o deminers to

cover approximately 6070 percent o each box in the allotted

time. During normal operations a CMR survey team surveys

up to 4 hectares (10 ac) in each three-week period. Tis gure

is based on ideal ground conditions and will drop as condi-

tions deteriorate.

Te ecient speed o CMR survey is possible largely be-

cause excessive vegetation removal is unnecessary. Tis is es-

TP1 TP2

TP3

TP4

TP5

TP6

TP7

SPBLU 26

BLU 26 BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26BLU 26BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26BLU 26

BLU 26BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26

BLU 26

40mm Rie Grenade

Figure 4. Village contamination.

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

16/85eature | the journal o ERW and mine action | summer 2013 | 17.2

Michael Creighton holds a Bachelor

o Arts in politics and a Ma ster o

Arts in international relations rom

the University o New South Wales(Australia). He served 11 years as an

ocer in the Royal Australian Engineers

beore establishing himsel as a project

operations and planning manager in the

explosive ordnance disposal and mine

action elds in 2001. Creighton has

since worked in Aghanistan, Bosnia

and Herzegovina, Cambodia, Iraq, Laos

and Lebanon in a variety o commercial

and United Nations Mine Action Service

positions. From 200 9 to 2011 Creighton

held the position o programme

manager or land release at the Geneva

International Centre or Humanitarian

Demining. In 2012 he joined Norwegian

Peoples Aid (NPA) and is currently the

operations manager o NPAs Surveyand Clearance Programme in Laos.

Michael Creighton

Operations Manager Norwegian

Peoples Aid

368 Unit 20

Ban Saphanthong, Sisattanak District

Laos

Tel: +61 267 323 090

Fax: +85621246813

Email: [email protected],

Website: http://npaid.org

NPA has ound that CMR survey is

the best survey approach in Southeast

Asia and potentially or other cluster

munition contaminated countries as

well. Providing answers to questions o

conrmation o contamination, it re-

mains cost-ecient and presents an e-

ective, low-tech clearance option that

allows rapid implementation. NPA has

already established more than 16 sq km

(6 sq mi) o CHAs in Laos using the

CMR survey approach (more than 238

CHAs o known and marked areas o

contamination). Tese CHAs were the

rst to be entered into the national data-

base, providing a basis rom which the

national authorities can set priorities and

plan the use o clearance resources.

See endnotes page 64

Atle Karlsen is the country director or

Norwegian Peoples Aid (NPA) in Laos.

Karlsen holds a Master o Art s in devel-

opment economics rom the Univer-

sity o East Anglia (U.K.) and a Master

in Management rom the BI Norwegian

Business School (Norway). Karlsen has

worked in mine action or more than

10 years ater accidently getting in-

volved in strategic assessment or NPA

and conducting an evaluation o the

global Landmine Impact Survey initia-

tive. He has worked as regional director

or NPA in South Arica and as a policy

and strategy advisor to NPA prior to

taking his current position in Laos. He

is a board member o the InternationalCampaign to Ban Landmines, the Clus-

ter Munitions Convention and the Land-

mine and Cluster Munitions Monitor, and

a co-c hair or the United Nations and

nongovernmental organization orum.

Atle Karlsen

Country Director/Policy Advisor

Norwegian Peoples Aid

368 Unit 20

Ban Saphanthong, Sisattanak District

Laos

Tel: +856 207 744 7000

Fax: +856 21246813

Email: [email protected]

Website:http://npaid.org

Mohammad Qasim is a skilled mine

action inormation management and

geographic inormation systems spe-

cialist and has more than 15 years

experience with various mine action

programs around the world. Qasim has

worked with Norwegian Peoples Aid

(NPA) since 2009. Qasim is currently

based in Laos as the regional inorma-

tion management supervisor, provid-

ing inormation management services

to NPAs Southeast Asia programs in

Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar (Burma),

Thailand and Vietnam, and assisting

national authorities where NPA is en-

gaged in national capacity development.

Mohammed Qasim

Regional Inormation Management

Supervisor

Norwegian Peoples Aid

368 Unit 20

Ban Saphanthong, Sisattanak District

Laos

Tel: +856 202 221 2802

Fax: +856 212 46813

Email: [email protected]

Website: http://npaid.org

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

17/8517.2 | summer 2013 | the journal o ERW and mine action | eature

Assessment o Vietnams NationalMine Action Program

by Ted Paterson [ GICHD ] and Thao Grifths [ VVAF ]

A December 2012 assessment conducted by the Geneva International Centre or Humanitarian De-

mining and the Vietnam Veterans o America Foundation ound that despite Vietnams well- received

mine action program reorm eorts, various actors, including economic and bureaucratic challeng-

es, continue hindering progress.

Vietnam suers rom extensive landmine and ex-

plosive remnants o war (ERW) contamination

as a result o the Vietnam War (19651973).1

Vietnamese oicials maintain that ERW contamination

covers one-ith o Vietnams total land area, or 66,000 sq

km (25,483 sq mi), and that an estimated 350,000600,000

tons o ERW still need to be cleared.2

Vietnams response to contamination has undergone a

number o distinct stages:

19751979. Te Ministry o Deence (MoD) organized

post-war clearance eorts as a campaign model to

clear essential livelihood spaces.

19792006. Military demining supported national

development projects.

20062010. On 29 April 2008, the government o

Vietnam initiated mine action reorms, including the

establishment o Vietnam Bomb and Mine Action Center

(VBMAC), a civilian entity housed within the Ministry o

Labour, Invalids and Social Aairs (MoLISA).2

2010present. Vietnams National Mine Action Pro-

gram (VNMAP) transitions rom military to civil-

ian oversight.

Financing Mine Action

VNMAP (also known as Program 504 in Vietnam as it

was established in Decree 504 by the Prime Minister in De-

cember 2010) is unded primarily by its national budget and

private investors, through our channelsthe MoD, other

ministries, subnational governments and private investors

as depicted in able 1.3 A number o international mine ac-

tion nongovernmental organizations (NGO) are active in

Vietnam and generally work with provincial governments.

International donors und these NGOs. Grants rom interna-

tional donors such as Australia, Germany, Ireland, Norway,

aiwan, the U.K. and the U.S. averaged about US$6.1 million

per annum in recent years and continue to rise.

Still, the bulk o unding comes rom Vietnams national

budget. Engineering CommandVietnams headquarters or

military engineering units, including demining unitsreports

that demining expenditures averaged US$20 million rom

1979 to 2006, then rose signicantly rom 2006 to 2010, driv-

en largely by a demand or demining support to inrastructure

projects a nd private investments.4 Te recession in 2011 led to

a reduction in public and private investment, delaying imple-

mentation or a number o approved demining tasks.

Source of funding Decision-makers Purpose Service provider

National budget Ministry of Defence Military requirements Military deminers

Other ministries Public investment Military

Sub-national governments Provincial-district-commune

investments

Local demining firms

NGOs

Private investors Private investors Private investments Firms

Table 1. VNMAPs unding channels.All graphics courtesy of the authors.

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

18/85eature | the journal o ERW and mine action | summer 2013 | 17.2

VNMAPs nancing pattern is distinctly dierent rom

that in most other mine/ERW-aected countries (Figures 2,

3 and able 2).

Outline o Recent Reorms

Evidence rom the Vietnam Landmine Impact Survey

(VLIS), as well as the World Bank and Asian Development

Bank, suggests that VNMAP is eective in terms o develop-

ment (e.g., support to public and private investment projects).5

However, the national program was not as eective in sup-

porting humanitarian mine action or bottom-up initiatives

o communities or or targeting clearance and mine risk edu-

cation (MRE) services based on casualties incurred.

In addition, Vietnam was unable to attract international

mine action support, in part because many donors reuse to

nance act ivities undertaken by the MoD. Tereore, VBMAC

initiated the reorm with a demining capacity under MoLISA.

VBMAC received some international unding, but this has

been sporadic.

In 2010 the government approved an ambitious National

Mine Action Program Plan or 20102025, with seven tasks

set or the period o 2010 to 2015:

Complete VLIS

Conduct unexploded ordnance (UXO)/landmine clearance

projects that support the governments socio-economic

development plans and ensure saety or the people

Establish a national database center

Develop the Vietnamese National Mine Action Standards

Implement MRE programs

Initiate victim assistance

Raise international awareness o the scale o Vietnams

contaminationIn 2011, the government established and appointed mem-

bers to a steering committee to oversee the VNMAP plan. Te

plan or 20102015 was extremely ambitious; nancing re-

quirements reached $110 mill ion in 2011 and continue to rise

in subsequent years to an annual average o almost $150 mil-

lion. Implementation was successul on some components,

$140

$120

$100

$80

$60

$40

$20

$0

USDmillions

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Delayed

Actual

Figure 1. Annual expenditures or survey and clearance operations.

Delayed

Actual

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

70,000

60,000

50,000

40,000

30,000

20,000

10,000

0

Hectares

Figure 2. Areas cleared by year in Vietnam.

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

19/8517.2 | summer 2013 | the journal o ERW and mine action | eature

he results were reported in December 2012 at the Vietnam

Mine Action Forum held 14 December 2012 in Hanoi. he

assessment ocused speci ically on the views o internation-al stakeholders.

Working with the Vietnam Veterans o America Founda-

tion (VVAF), GICHD developed a simple questionnaire and

distributed it primarily through email to donors, U.N. agen-

cies, operators, government ministries and provincial author-

ities involved in mine action. Ten, on a trip to the cities o

Hanoi, Quang ri and Hue in October 2012, an assessment

team rom VVAF and GICHD met with 19 organizations to

review responses and ask ollow-up questions.

Te assessment team obtained 21 questionnaire responses

which were broken down into the ollowing categories: Operators (7)

Donors (5)

Government ministries/oces (5)

Provinces (2)

U.N. agencies (1)

Consultants (1)

Findings

In brie, the assessment ound t hat international stakehold-

ers approved o VNMAP, but current progress disappointed

them. More specically, the majority o respondents were hap-py with VBMACs establishment in 2008 and with the an-

nouncement o a national program in 2010 or a variety o

reasons, as these actions showed the ollowing:

Signied growing awareness within the Vietnamese gov-

ernment o the mine/UXO problem

Included provision o MRE and victim assistance

Suggested greater transparency and a level playing eld

(i.e., national standards that all operators would be re-

quired to meet)

such as VLIS, but progress was uneven overall. In some cas-

es, the international community seemingly remained largely

unaware o new initiatives launched by VNMAP.

Assessment

In June 2012 Vietnamese mine action oicials request-

ed that the Geneva International Centre or Humanitarian

Demining (GICHD) undertake an assessment o VNMAP.

Government

Donor

Private

Figure 3. Financing VNMAP in Vietnam (2009 ).

Government

Private

Donor

Figure 4. Financing mine action in other countries.3

Map o Vietnam.

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

20/85eature | the journal o ERW and mine action | summer 2013 | 17.2

Indicated that a balanced ap-

proach might emerge, with more

demining targeted to support

community development and re-

duce the number o victims

Tough the national program repre-

sented a signicant advance, several aws

were noted, including the ollowing:

Vietnams unwillingness to join

the Convention on Cluster Muni-

tions

Te ailure to make VBMAC ul-

ly civilian

Lack o oversight, as VBMAC

serves as both a national mine

action center and as a demining

operator

Most international stakeholders

were unhappy with the rate o imple-

mentation or one or more components

o the 20102015 plan. Specic con-

cerns included the ollowing:

Delays in completing the nation-

al standards

Failure to appoint ull-time personnel to VBMAC

Lack o communication by national ocials

International stakeholders avorably mentioned a number

o recent actions, including the attendance o VBMAC ocials

at Mine Action Working Group meetings and the meeting o

the rst Vietnam Mine Action Forum in December 2011.

Interestingly, most international stakeholders seemed

unaware o progress on certain ronts. For example, they

were not aware o MRE messages broadcast on television in

Vietnam. Nor did they know that highly contaminated prov-

inces received national budget transers o approximately $7.5

million per year in 2011 and 2012 or demining projects.

Concerns raised most oen were the continuing depen-

dence o VBMAC on the MoD, VBMACs lack o progress in

draing national standards, establishment o a true mine ac-

tion center and the absence o a national database center.

Operators emphasized that they worked closely with pro-

vincial authorities and were not ul ly aware o developments

in Hanoi. Most said relations with provincial authorities were

improving steadily; a ew expressed concern that the new na-

tional program might create problems or operators because o

additional registration requirements.

International respondents presented a number o hypoth-

eses as to why implementation lagged:

Dem

$160

$140

$120

$100

$80

$60

$40

$20

$0

2011 201215

Oth

VA

MR

Figure 5. Annual nancing requirements or VNMAP 20112015.

YearFinancing ($ millions)

Total funding International as% of total

Government& investors

Internationalgrants3

07 $ 49.50 $ 3.95 $ 53.45 7.39%

08 $ 69.50 $ 7.64 $ 77.14 9.90%

09 $ 84.17 $ 4.20 $ 88.37 4.75%

10 $ 116.70 $ 7.07 $ 123.77 5.71%11 $ 50.73 $ 7.89 $ 58.62 13.46%

Table 2. Annual nancing requirements or VNMAP 20112015.

Recent economic downturn pushed mine action lower

on the government agenda.

Bureaucratic battles delayed progress (e.g., MoD wanted

to keep ul l control o demining).

Unresolved policy issues (e.g., the relative roles o na-

tional ministr ies and provincial governments) hinderedimplementation.

Inaccuracies in initial assumptions and policies, and

mine action ocials now realize these should be amend-

ed (e.g., VBMAC should not have been created as both a

regulator and an operator).

National Stakeholders

National stakeholders ocused more on the work that has

been done to get VNMAP operating, and mentioned the

ollowing:

Progress on VLIS and MRE Establishment o a high-prole steering committee

ransers rom the state budget to provinces to und de-

mining projects

he Ministry o Planning and Investment also empha-

sized that mine action is a priority or both oicial devel-

opment assistance and in its priorities issued to donors.

Ministry oicials also spoke o plans or 2013 that await-

ed Prime Minister Nguyen an Dungs approval. hese in-

clude the ollowing:

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

21/8517.2 | summer 2013 | the journal o ERW and mine action | eature

Ted Paterson has a background in in-

ternational development, working with

nongovernmental organizations, re-

search and education institutes, and

consulting rms, as well as in an inde-

pendent consultant capacity. Paterson

has been active in mine action since

1999 and has worked on socioeco-

nomic and perormance-management

issues. Paterson joined the Geneva

Centre or International Humanitarian

Demining in 2004 and serves as se-

nior advisor on strategic management.

He has a Bachelor o Commerce rom

the University o Manitoba (Canada),

a Master o Arts in economics rom

York University (Canada) and a Mastero Science in development economics

rom the University o Oxord (U.K.).

Ted Paterson

Senior Advisor, Strategic Management

Geneva International Centre

or Humanitarian Demining

7bis, avenue de la Paix

P.O. Box 1300

1211 Geneva 1 / Switzerland

Tel: +41 22 906 1667

Email: [email protected]

Skype: gichd.t.paterson

Website: www.gichd.org

Thao Grifths has been the country di-

rector o Vietnam Veterans o America

Foundations (VVAF) Vietnam oce

since 2007. Previously, Griths worked

as the senior Vietnamese program o-

cer at VVA F and also held positions at

Microsot and the United Nations De-

velopment Programme. Griths holds

a Master o Arts in international rela-

tions rom American University (U.S.)

and a Master o Science in systems

engineering rom Royal Melbourne In-

stitute o Technology (Australia).

Thao Griths

Vietnam Country Director

Vietnam Veterans o AmericaFoundation (under the International

Center)

No 20, Ha Hoi St

Hanoi / Vietnam

Tel: +84 4 733 9444

Email: [email protected]

Skype: thaogriths

Website: http://www.ic-vva.org/

Establishment o a national regu-

latory oce

Division o VBMAC to create a

new Viet Nam Mine Action Coor-

dination Centre (VNMACC) and

a separate civilian operator

Appointment o qualied person-

nel to VNMACC on a ull-time

basis and to a new location

Assuming approval is obtained,

these plans address the majority o the

concerns raised by stakeholders.

Conclusions

While VNMAPs approval was widely

welcomed, the pace o implementation

disappointed many stakeholders. Te di-

vision o roles and responsibilities among

MoD, VBMAC and the proposed regula-

tory oce remains unclear to most stake-

holders, and this represents a signicant

concern to those involved. Contributing

to disappointing progress on other mea-

sures envisaged, the delay in providing

adequate human and nancial resources

to the mine action center is a core prob-

lem. However, better progress can be ex-

pected in 2013 and beyond, assuming that

the plans and budgets already prepared

are approved.

See endnotes page 64

17 YEARS / 40 ISSUES / SEARCHABLE CONTENT

Clearance Operations Age and Gender Issues Mine/ERW Risk Education Challenges in Africa Mine Action Disability Is-sues and Rights of Persons with Disabilities Small Arms and Light Weapons Urban Land Release NGOs in Mine Action Food,

Water and Health Security Issues Cluster Munitions Government Stability and Mine-action Support Victim Assistance

Deminers on the Front Lines Information Systems and GIS Mapping The Middle East Training and Capacity Development Le-

gal Instruments Non-state Actors Physical Security and Stockpile Management Land Cancellation and Release ...and more.

HTTP://CISR.JMU.EDU/JOURNAL/PAST.HTML

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

22/85eature | the journal o ERW and mine action | summer 2013 | 17.2

Securing Health Care Rights orSurvivors: Developing an Evidence

Base to Inorm Policy

Analysis o current literature on landmine/explosive remnants o war casualties in Cambodia, Laos

and Vietnam reveals faws in recording systems. An integrated course o action should aid mine ac-

tion and public health communities in preventing incidents and providing care to survivors.

by Jo Durham [ University o Queensland ]

he United Nations Convention on the Rights o Per-

sons with Disabilities (CRPD), adopted by the Gener-al Assembly in December 2006, aims to promote and

protect the rights o people with disabilities (PWD). It recog-

nizes that PWDs have the right to the highest attainable stan-

dard o health without discrimination, and should be able to

access the same range, quality and standard o ree or aord-

able health services as people without disabilities, as well as

any specialized health resources they may require.1 Te pro-

tections o the CRPD, however, only apply in countries that

have become states parties to this convention. Te rights o

landmine and cluster munition sur vivors are urther protect-

ed by the Convention on the Prohibition o the Use, Stockpil-

ing, Production and ranser o Anti-personnel Mines and on

Teir Destruction (Anti-personnel Mine Ban Convention or

APMBC) and the Convention on Cluster Munitions (CMC),

again, only in states that sign and ratiy these conventions.2,3

In order to ulll these international obligations, a con-

sistent and comparative description o injuries, risk actors

and comorbidities is required to inorm the health decision-

making and planning processes. Tis is especially important

as a substantial number o nonatal injuries result in perma-

nent disabilities, which can put signicant strains on existing

health care systems.4,5 Valid estimates are also needed to cal-

culate the cost-eectiveness o interventions.6

Using Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam as examples, the

World Health Organization (WHO) signicantly under-

estimates landmine and explosive remnants o war (ERW)

injuries. It is important to note that only Laos is a state party

to the CRPD and CMC. Cambodia is a state party to the

A survivor rom Laos, 1998.Photo courtesy of Sean Sutton/MAG.

-

7/27/2019 172 Online

23/8517.2 | summer 2013 | the journal o ERW and mine action | eature

APMBC, but not the others. Vietnam is not a state party to

any o these conventions; Cambodia and Vietnam have signed

but not ratied the CRPD. Nevertheless, this underestimation

o landmine/ERW injuries means that survivors are more

likely to be excluded rom health systems planning, and this

has important ethical and social justice implications.

Estimates o Mine/ERW Injury-related Fatalities

Te author systematically studied the peer-reviewed

health literature examining landmines and ERW deaths and

disabilities in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam, nding only six

relevant studies. One o the articles ocused on Laos while

the remaining ve examined Cambodias situation. O the six

studies, ve were undertaken beore 1996. Furthermore, our