#129 In Practice, JAN/FEB 2010

-

Upload

hmi-holistic-management-international -

Category

Documents

-

view

224 -

download

3

description

Transcript of #129 In Practice, JAN/FEB 2010

Collaborating Into the Future—From the CEOby Peter Holter

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2010 NUMBER 129 WWW.HOLIST ICMANAGEMENT.ORG

healthy land.sustainable future.

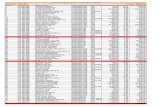

Book Review . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18Certified Educators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19Marketplace . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

NEWS and NETWORK

LAND and LIVESTOCKWinter Bale Grazing—Feeding the SoilKELLY SIDORYK . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .10

Bringing Carbon Back to Agriculture— A Bedded Pack Management SystemJOHN THURGOOD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12

CRP GrazingKELLY BONEY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14

FEATURE STORIES

HolisticFinancialPlanning isa critical stepto help peopleachieve theirholisticgoal.Learn moreabout how

the Campbell family is using HolisticFinancial Planning to improveprofitability on page 5.

As HMI moves into its 26th year as aninternational non-profit, our mission remains what it has always been: to reverse the degradation of private and

communal land used for agriculture andconservation, restore its health andproductivity, and help create sustainable andviable livelihoods for the people who depend onit. How do we do that? Using our statement ofpurpose— Advance the practice andcoordinate the worldwide development ofHolistic Management to heal the land whileimproving quality of life and creatinghealthy economies—as our compass, wedevelop those strategies that get us there, withthe greatest benefit for all and the biggest bangfor the buck.

HMI’s Board of Director and staff met at theannual Board meeting in November 2009. Out ofthat meeting came a unanimous andunequivocal call to more aggressively andpurposefully pursue opportunities forcollaboration and collegial cooperation withindividuals and organizations who share ourmission. And there are many; farmers andranchers in the U.S. and other parts of the worldwho seek to create a legacy of good stewardshipand leave a healthier resource base for the nextgeneration; government agencies who, like us,support individuals and communities in theirefforts to implement sustainable landmanagement practices; conservation and otherenvironmental organizations contributing topreserving important habitats; academicinstitutions who teach the next generation aboutsustainability and prudent stewardships; andbusinesses and corporations participating increating healthier food systems and sustainableresource management.

Another area of exploration and

collaboration will be the carbon sequestrationarena. There’s ample evidence that the kind ofmanagement practices HMI and others promoteand help implement, lead to an increase in soilcarbon and, therefore, sequester larger amounts ofcarbon dioxide from the air than industrial orconventional agriculture. We’re working onstrategies to inform the public debate and tosupport our network of practitioners in theirefforts to qualify for – and access – carbon credits.

Clearly, collaboration is a major strategicdriver in our plan for the next five years. And soare effectiveness and results. Whatever weundertake in terms of projects, trainings,collaborative ventures, and other initiatives, wewant to be sure we achieve the intended results onthe ground and that we have the data to prove it!So we plan, monitor, control, and re-plan.

Now that we have outlined our mission,purpose, and core strategies, here’s what it’ll looklike on the ground. Here some of the highlights ofour activities over the next three years:

In six Northeastern states, close to twohundred beginning women farmers willparticipate in a three-year whole farm planningtraining program that will help them make theirfarms more profitable and their land healthierand more productive;

Our work with Horizon Organic continues and will expand to include work with their 500family farms

Our Data & Documentation Division spans allprojects and departments, making sure we collect,analyze, and disseminate data relevant to ourcommunity and collaborators.

We will develop and roll-out a new product:Holistic Management Remediation on Oil & GasDrilling Sites;

CONTINUED ON PAGE 2

I N S I D E T H I S I S S U E

FINANCIAL PLANNING

Influence of Predators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2Why Monitor?Control What?TONY MALMBERG . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

Financial Planning—Make the CommitmentDON CAMPBELL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

Getting It Done—Building a Financial Management TeamROLAND KROOS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6

Holistic Management® Financial PlanningHuman Creativity and TechnologyANN ADAMS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Data Mine: Improving Forage DistributionUtilization & Livestock Production—Planned GrazingMATT BARNES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

Learning From Two Environments—The Need for Plant RecoveryTINA WINDSOR & BLAKE HALL . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

2 IN PRACTICE � January / February 2010

Holistic Management International works to reverse thedegradation of private and communal land used foragriculture and conservation, restore its health andproductivity, and help create sustainable and viable

livelihoods for the people who depend on it.

STAFFPeter Holter, Chief Executive Officer

Tracy Favre, Senior Director/ Contract Services

Jutta von Gontard, Senior Director / Philanthropy

Kelly King, Chief Financial OfficerAnn Adams, Managing Editor, IN PRACTICE and

Senior Director of Education

Donna Torrez, Manager: Administration & Executive Support

Mary Girsch-Bock, Communications AssociateValerie Grubbs, Accounting Associate

BOARD OF DIRECTORSBen Bartlett, Chair

Ron Chapman, Past ChairRoby Wallace, Vice-ChairJohn Hackley, Secretary

Christopher Peck, TreasurerSallie Calhoun Mark GardnerLee Dueringer Clint JoseyGail Hammack Jim McMullanIan Mitchell Innes Jim ParkerDennis Wobeser Jesus Almeida Valdez

ADVISORY COUNCILRobert Anderson, Corrales, NMMichael Bowman,Wray, COSam Brown, Austin, TX

Lee Dueringer, Scottsdale, AZGretel Ehrlich, Gaviota, CA

Dr. Cynthia O. Harris, Albuquerque, NMLeo O. Harris, Albuquerque, NMEdward Jackson, San Carlos, CA

Clint Josey, Dallas, TXDoug McDaniel, Lostine, OR

Guillermo Osuna, Coahuila, MexicoSoren Peters, Santa Fe, NMJim Shelton, Vinita, OK

York Schueller, Ventura, CA

The David West Station for Holistic Management

Tel: 325/392-2292 • Cel: 325/[email protected]

Joe & Peggy Maddox, Ranch Managers

HOLISTIC MANAGEMENT IN PRACTICE (ISSN: 1098-8157) is published six times a year by

Holistic Management International, 1010 Tijeras NW, Albuquerque, NM 87102, 505/842-5252, fax: 505/843-7900;

email: [email protected].; website: www.holisticmanagement.org

Copyright © 2010

healthy land.sustainable future.

We’ll be expanding our Kids on the Landeducational program in Texas and other Western states;

Periodically and on demand, we’ll coordinatecustomized regional workshops;

Customer-driven consulting with ranchers,farmers, and businesses will expand all across the country;

We’re expanding our Certified Educatortraining

Provide further outreach and education with“The First Millimeter” the PBS documentary

Intensified Collaboration with HMI affiliatesSupport of Holistic Management field days

in key areas of the country and support ofManagement Clubs;

Collaborating Into the Future continued from page one

The New York Times recently publishedan essay by Olivia Judson entitled“Where Tasty Morsels Fear to Tread.” Init, Judson talks about her experiences

in Romania; which she describes as the“predator capital of the world,” as Romaniais home to Europe’s remaining bear, lynx,and wolf populations.

Although no longer a real threat to thehuman race, predators remain a driving forcebehind the behavior of all of nature’screatures, great and small. While injury andultimately death occur on a routine basis innature, what predators really change is thenatural dynamic that other creatures exist in.According to Judson, what predators do reallywell is create an atmosphere of fear.

What other living creatures do in responseto this atmosphere of fear is create an anti-predator environment; traveling in herds,flocks, and schools. What this group dynamicdoes is enable animals to relax and do thethings that they need to do, such as eating,sleeping, or finding a suitable mate; allactivities that diminish or stop when ananimal is basically on its own.

It’s not only certain activities that stop. Thepresence or threat of predators also determineswhat direction animals travel in. Judson goeson to cite the behavior of the vervet monkey, asmall African monkey that has several naturalpredators which include leopards and

baboons. The monkeys will avoid the areasthat leopards and baboons frequent, even if thefood supply is good. Judson also notes thatother creatures behave in similar fashion.Bumblebees avoid the flowers that typicallyattract spiders, and impala avoid locationswhere lions are frequently found.

This “fear factor” also influences otheraspects of an animal’s life, frequently resultingin a slower growth rate and less reproduction.In fact, Judson notes that birds that perceivethe presence of predators may skip breedingaltogether. An indirect result of this climate offear also affects plants in the area as well.When animals avoid certain areas, the plantsthat typically are eaten for survival suddenlyhave a chance to grow and flourish;something they could not do before. Forexample, prior to the introduction of wolves inYellowstone National Park in the 1990s, youngwillow trees were never given a chance to growto mature trees due to the propensity of elk inthe area that enjoyed nibbling on the trees.With the introduction of the wolf, elk nowperceive the area…and the trees asdangerous, thus enabling the willow trees togrow to maturity.

While many of us will never be able toperceive the world through the eyes of nature’sprey, as Judson so eloquently states, “Whenpredators vanish, our planet becomes a safer,but poorer place.”

In addition to the examples above, we’llcontinue to develop our contract servicesopportunities in the corporate sector which willhelp us monetize and further our non-profiteducation and training programs, furthersupplemented by grants, donor initiatives, and fees. We will continue to strengthen the HMI brand and support our affiliates in the U.S.and abroad in their efforts to effect change in their communities.

As always, the staff and Board at HMI aregrateful for your dedication, patience, andperseverance. Many thanks to you all! Please giveus a call so we can discuss with you how to helpyou spread the word about Holistic Managementin your area.

Influence of Predators

Why don’t we get our planning,monitoring, and controlling done? Ihave repeated the feedback loop somany times, it has become a

mindless mantra. Plan> Monitor> Control>Replan>; Plan> Monitor> Control> Replan???Monotonous repetition has blurred the distinctand necessary purpose and mindset of eachindividual step. Our sloppiness blursmonitoring toward simple record keeping.Grasping attempts to regain control boil into“busyness,” just to be busy. Monitoring andcontrolling are ineffective until we realize theyare an interactive event.

Creating your RecordNot that record keeping is bad. Records give

us useful information for planning in futureyears by documenting actual events—during themoment we think we will never forget significantevents. But over time, our memories modifytoward the dramatic exaggeration or we simplyforget. Good decision-making requires accuraterecords for better future planning.

Accurate records provide critical perspectivetoward the limits of our abilities. Without thisperspective we create unrealistic plans; plansdoomed to fail.

Planning identifies the desired future record.Monitoring provides reference to our reality,relative to our plan. Control gets our reality backto the plan. It sounds so simple, so why is it sodifficult? Let’s revisit our analogy used by Allan Savory.

He likens meaningful monitoring to drivinga car down the highway. Meaningful monitoringlooks out the front window so we can apply thebrakes and turn as we enter a curve. Looking inthe rear view mirror does not provide feedback tokeep us on course. The rearview mirror providesa record of where we have been. Manymonitoring plans are actually records and do not provide data necessary for making dailymanagement decisions. For example, on theranch we owned in Wyoming, the Bureau ofLand Management monitoring documentedchanges in species diversity, bare ground, andplant density. These records provide a necessarydocumentation of what things look like out therearview mirror.

Knowing the route we took last time, the time

that route took, the gallons of gasoline, etc., giveus perspective on planning the next trip, but notin navigating our trip in the “live, threedimensional” present. Records from past tripsinform our plan. Executing the plan creates the record.

Monitor What?The first big transformation toward

practicing Holistic Management happens whenwe start planning. Most of us look forward todoing our grazing plan and monitoring plantgrowth to regularly adjust our recovery period. Ittook much longer for me to get into the habit ofHolistic Financial Planning and my wife Andreawould drag me by the ear to the planning table.The fact remains that we have nothing tomonitor or control until we have a plan! Whatshould we have in a plan?

Everyone knows that a plan identifies 1) where we are starting from, 2) where aregoing, 3) how we are going to get there, and 4) how we know when we have arrived. However,what makes Holistic Management different fromothers is that we identify early warningindicators. This needs to be done now and statedin our plan.

How do we think through identifying effectiveearly warning indicators? Too often we spendtime and money on factors that don’tsignificantly affect progress toward ourholisticgoal. To begin, think of the potential100% perfect outcome, whether a crop, grass, afield of potatoes or our cash flow. Think of waysto prevent lost potential. Ask, “What are the earlywarning indicators that will prevent that loss?”

Back to our Wyoming ranch scenario. The

BLM monitoring provided good records of resultsbut not on controlling our grazing plan. Ourgrazing plan estimated ADA, on a paddock basis.If we have to move before our planned time dueto lack of feed, we immediately know that we are over stocked. This monitoring allows us tomake an immediate adjustment in stocking rates that will minimize our necessary reduction.We monitor plant re-growth daily and adjust our moves to minimize overgrazing. Monitoringplant re-growth and residual cover are twomeans of looking out the front window andadjusting our actual grazing to control it towards our planned grazing. These two forms of monitoring help control our grazing plan.

Another example would be, what if we miss the opportune time to harrow and weedsrob some moisture and nutrients from our crop? We are suddenly at 90% of the plannedpotential. We will never get that 10% back again.It is gone forever. If we are three days late onirrigation and cause plant stress, we have lostanother 3%, and are down to 87%. If we missanother irrigation by 5 days, it might take usdown to 77% of our potential. Finally, if we are a week late harvesting, we might end up with a crop that is 60% of the initial 100% potential.

Much of agriculture literature is designedaround “best practice” to achieve the 100%potential. Perfection may not be the bestmarginal reaction. As we think through thedesign of our early warning indicators, thinkmarginal reaction towards our holisticgoal. Forexample, if it takes 20 hours a week to retain thelast 5% of potential, that time might be bestspent playing softball with our children.Therefore, we may only plan for a 95% crop.Plan early warning indicators toward ourholisticgoal to know exactly what to look for asexecution begins to unfold. Don’t get confused by“best practices” that only consider a crop or agrazing event.

Execute MeansThe best of plans are useless unless they are

executed. This means control. Back to the caranalogy, we control the direction and speed ofthe car as we navigate through heavy traffic androad interchanges. Our plan identified that if wedrove the speed limit we would approach exit23B, to cross the second bridge into Denver,Colorado, sometime between 2:00 and 2:15 PM.We might have coasted on cruise control forhours and monitored our speed and timecasually. Having noted little deviation from ourplan we relax until we approach 2:00 PM.

Number 129 � IN PRACTICE 3

CONTINUED ON PAGE 4

Why Monitor?Control What?by Tony Malmberg

Monitoring and controlling are ineffective until we realize they are an interactive event.

4 IN PRACTICE � January / February 2010

Knowing we are not exact, we need to intensifyour monitoring to control our actual course toalign with our planned course.

We need to be “full-on” as the exitapproaches because if we miss this one it’sseveral miles and maybe an extra hour of drivingto get back on course. To control our potentialfive-hour trip we must prevent missing this exitand making it a six-hour trip. We need to haveour eyes peeled, our hands on the wheel and ourmind in the middle. We have a constant

exchange of monitor-control-monitor-control to navigate the exit, lane change, turn to a one-way street, lane change, turn to parkinggarage, and finally stop. The high-speedinteraction between monitor and control resultsin creating the record we planned. Our planprepared us for the window of time to applyacute awareness to monitor and control for thebest marginal reaction.

In the grazing plan example above, we mightspecify that one inch of growth per day signalsfast growth and we speed up our livestock moves.In the farming example, we might specify thatweeds with a density of 4-inch spacing and 2-inch height signal a need to cultivate. Thesemonitoring “red flags” specify a predeterminedaction that we can readily execute.

Sticking Our Head in the SandThere are times that we just flat get behind.

We seem to have a default mechanism kick inand we just look the other way. Ignoring is notthe same as controlling. At this stage we becomelike a small child, covering our eyes to becomeinvisible. We have a tendency to “look away” or“explain away” the red flag an early warningindicator provides. For some reason we haven’tregistered the urgency and best marginalreaction of keeping on course.

I suggest this default takes us back to poorplanning. If our plan doesn’t registercommitment to controlling the plan, it was abad plan. The plan must clearly connect our

need to control to our desired quality of life. If we have a hard time getting out of bed in themorning, our plan didn’t connect to our quality of life statement. We need to revisit ourholisticgoal.

In the early part of the worst drought inrecorded history, I recognized we wereoverstocked on our Wyoming ranch. We relied onpasture cattle and destocking directly affected ourcash flow. I knew our cash flow and debt servicewere already marginal. I became depressed andwould struggle to get out of bed and monitor the pasture utilization. I knew I would find 700head of cattle bunched in the corner andbawling for fresh pasture. The tendency was toignore the situation and hope for rain. And Imay have, had it not been for a planned earlywarning indicator.

We were into the fourth year of drought and Ilearned that rain after June 20 did not result insignificant growth in our sagebrush steppeenvironment. The previous fall we had decentmoisture so we planned to increase our stockingrates. However, I knew we were pushing ourpotential. We planned the early warningindicator demanding action if we did not havesignificant rain. I took a huge red ink markerand drew a line down through our grazing planand wrote DDD at the top of the line, at thebottom of the line, and in the middle of the line.DDD- Drop Dead Date.

No matter how how depressed, how lethargic,or how much I wished to ignore the situation, Icould not ignore that big red line and DDD. It isimperative to define early warning indicatorswhen we do our plan. If we clearly identify thereason for the red flag and the necessary action,it will more likely be implemented in a time ofstress. I called trucks and we destocked to a levelthat got us through the year.

Our tendency to ignore early warningindicators happens most often in controlling ourfinancial plan. If we fail to check our actualspending against our financial plan by the 10thof the month, it is in fact, an early warningindicator. This may be fine if you have a strongsense that you are on track and coasting. Butwhen we get behind in monitoring and we knowwe’ve experienced several unplanned spendingevents, we often panic. In a grasping effort toregain control we place a moratorium on ourspending. We think we are controlling our planbut once again this attempt at control is justanother way of sticking our head in the sand. Wemay actually be causing damage.

How? By freezing spending we gain a false

Why Monitor? continued from page three sense of security. We developed a HolisticFinancial Plan, and we did not plan for anexpense that wasn’t rigorously scrutinized. Weare monitoring and controlling so our costs areactually investments toward achieving our plan.Freezing spending may starve necessary inputsfor creating our desired outcome. We run aroundbeing busy and are soothed by activity that is notcontrolling our plan.

Still another form of early warning indicatorsis failed testing questions. Brushing failed testingquestions aside fails to “control.” In the case ofearly warning indicators and failed testingquestions, “control” means addressing theuncomfortable situation. A bad situation has atendency to get worse and the more we prolongcontrol the more we veer off course. When atesting question fails it usually means to modify

our proposed action or revisit our holisticgoal.For example, let’s say building a permanent

fence fails the marginal reaction test in favor ofusing a temporary electric fence. An examplemight be spending $10,000 to build one mile ofpermanent fence to minimize overgrazing. If ourinterest cost is 10%, we have an annual cost of$1,000. If the life of the project is 49 years, ourdepreciation is $250. We will have an annualmaintenance fee of $100, at least. So we have atotal annual cost of $1,350, without consideringretiring the initial investment.

If we have temporary electric fence, already,and it takes two hours to put up and take downthe fence, $1,350 is a pretty good marginalreaction for labor and a little wear and tear. Yet,we often blunder ahead because we don’t want totrudge up the hills and fight the brush. Wereason our way around the testing questions toavoid something we don’t want to do!

In this example, the failed test may meanrevisiting our holisticgoal and specifying our

The fact remains that we have nothing to monitor or control until we have a plan!

. . . I took a huge red ink marker and drew a line

down through our grazing plan and wrote DDD at the top of the line, at the bottom of the line, and in the middle of the line. DDD- Drop Dead Date.

desire for shade on hot days and saving time toopen a gate rather than put up a mile oftemporary fence. Be careful not to lie to yourselfin testing decisions. Ignoring a failed testingquestion is an early warning indicatordemanding action. In this example, the actiondirects us to use temporary fence or change ourholisticgoal.

Do Nothing to Get MoreThe most damaging instance of mindless

activity is addressing the social weak link withaction. This is the only testing question that isnot a pass/fail test. It tells us to be aware of socialissues and adjust our action to address thoseconcerns or be forewarned of what might happenif we proceed. Those of us who have “been thereand done that,” recognize the wisdom in BudWilliams rule in handling cattle: Slow is Fast. Hisadvice especially rings true in the social weaklink. If we “stick our head in the sand” andblunder ahead, we could make a bad situationworse. In this case, responding to early warningindicators means doing nothing.

Corporate structure and government agenciestend to exacerbate the social weak link by forcing imposition. This provides a false sense of control in a situation asking for pause. Don’tconfuse “control” with doing something just to do something. When dealing with the

complexity of nature and human nature,“control” means self-control.

Making Monitoring MeaningfulFinally, we will never find the gumption to

“get ‘er done,” if our plan is not relevant to eachof us in our own individual way. In the mostbasic sense this means totally comprehendinghow monitoring and controlling will create ourdesired quality of life. If we grasp and internalizethat connection, we want to get up in the

morning. If life is getting in the way, we need torevisit our plan because the plan should bedirectly proportional to creating our desiredquality of life.

We have a huge investment of time andenergy in our plan. We identified decision

Number 129 � IN PRACTICE 5

makers, those with veto power, and our futureresource base. An unexecuted plan, makes theplanning a very poor marginal reaction. Timewasted. A replanning event is simply anacknowledgement that we did not have buy-in to our plan, or we did not adequately identifyearly warning indicators in our plan, or wedidn’t have a plan meaningful enough to control.

Our feedback loop may be more effective if we stop thinking of it asPlan>Monitor>Control>Replan. There is, infact, a clear disconnect between plan andmonitor. A plan is completed and set aside. It isdone. There is not a disconnect between monitorand control! There is a constant interactionbetween monitoring where we are relative to theplan and nudging control to keep us on plan.This interaction, back-and-forth continues untilthe plan is complete. The need of a replan is dueto the failure of identifying early warningindicators in the plan or failing to respond toearly warning indicators. Maybe our feedbackloop should read: Plan. Monitor and Control.Replan if we fail to Control. In other words,Plan>Monitor><Control>Replan.

Tony Malmberg is a Certified Educator inUnion, Oregon. He can be reached at:[email protected] or 541/663-6630.

We reason our way aroundthe testing questions to

avoid something we don’t want to do!

CONTINUED ON PAGE 17

Our year end is August 31st. Last year, wespent a lot of time planning. I amamazed, encouraged, and impressed with what a powerful tool Holistic

Financial Planning is. I have always knownthis, but it becomes even more obvious whentimes are tough.

Most of you are likely on a calendar year. Iencourage you to Commit, Pledge, andPromise yourself that you will do a properfinancial plan now. I am confident this would beone of the best investments of your time andmoney that you could make. If you need help,seek out a trusted friend or your managementclub or a Certified Educator. One of the comments our son Mark made during the tourswe hosted was: “Financial Planning is the hardestand the most important work we do during theentire year.”

We began our planning with looking at thebig picture.

1. Our quality of life is excellent. We like whatwe do and we want to continue to raise ourfamilies here.

2. We are willing to adjust our standard ofliving in the short term because we believe thelong term will be better.

3. We think there is a future for familyranches.

4. We think a cow yearling operation is bestsuited to our ranch.

The challenge is how do we make it pay?

Financial Planning StepsWe looked at four scenarios. We did a detailed

financial plan for each one (all eight steps) andvaried our cow numbers. We planned for 550-pound (248-kg), 650-pound (293-kg), 700-pound(315-kg), and 750-pound (338-kg) cows. We usedconstant prices for our cattle sales. Fall cull cowsat $.22, summer culls at $.45, yearling steers 825-pound (371-kg) at $1.00, and open heifers 825-pound (371-kg) at $.85.

We projected all four scenarios out for threefull years. The bottom line was that the more cows

we had the better off we would be. These prices arewhat we felt comfortable projecting. They are nota forecast or meant to be used by anyone else. Useyour own projections.

This was a very useful exercise and helped ushave a realistic look at our business and what thefuture might hold. After finishing this exercise, wedecided that we needed to focus on the upcomingyear. Our goal is to make a profit this year so thatwe will be here next year to deal with whatever thefuture holds.

We identified our weak link as resourceconversion. The single most important thing wecan do to be more profitable is to grow moregrass. This extra wealth will contribute to cashflow if harvested into biological capital, improvedland, and sustainability if left on the land.Identifying our weak link allowed us to sort ourexpenses into W (wealth generating), I(inescapable), and M (maintenance expenses).This allows us to spend our money wisely.

We brainstormed on ideas to improve ourfinancial plan. We came up with nine ideas andput some numbers on all of them. We will

Financial Planning—Make the Commitmentby Don Campbell

6 IN PRACTICE � January / February 2010

In the early ‘90s I remember a rancher fromnorthern Montana asking me when I would beteaching the next Holistic Management®Financial Planning workshop. I was

perplexed by his question because he had alreadyattended this workshop twice. He immediatelyresponded that he wanted his wife to attend thisworkshop so she could do the financialmonitoring for the ranch. The only problem wasthat neither he nor his wife had any passion(interest) in doing the financial planning.

In the mid ‘90s I attended an EntrepreneurWorkshop by Ernesto Sirrolli. After listening toErnesto, I understood why so many ranchmanagement teams still don’t effectively do thefinancial planning as required by HolisticManagement. Even if every team member hasattended a Financial Planning course, no amountof training will substitute for passion.

At this workshop Ernesto went on to explainwhat makes an entrepreneurial business great. Firstand foremost it takes great passion combined withcertain management skills: technical, financial,and marketing. Ernesto shared another discoverywith the group, “I’ve never met one person who isequally passionate about and capable of doing thesethree skill sets well.” There in lies the challenge tomanaging a ranch holistically.

The Three-Legged StoolIf we think about entrepreneurship as a three-

legged stool, the three legs are:Technical – To be able to create a high quality

product or serviceMarketing – To be able to effectively market

whatever it is you are producingFinancial – To understand what it costs to

produce this product and be able to manage cashflow so you are profitable (Income in and expensesout)

He has met people who may be skilled in twoareas (technical + financial) or (technical +marketing). Because of this fact, there is no suchthing as a one-person business. A person may try toprovide all of the skills. But when this personbecomes stressed from trying to do everything, theystop doing the tasks they are least passionate about.In many ranch businesses, the financialmonitoring and control stops when the cows beginto calve in the spring and is not resumed until thecalves are sold in the fall.

What’s the most urgent task for you in yourbusiness? Ernesto says it is to sit in front of a

mirror and determine what you are trulypassionate about. If you like raisinglivestock/crops but hate financial planning and/ormarketing, admit it. Our natural inclination is toassign this financial planning to another teammember, but what happens if this team memberhas no interest in financial planning either. Asone rancher in Wyoming recently told me, “Ialready know that I procrastinate when it comes tothe financial monitoring and control, so I askedmy sister to help me. However, I found my sisterprocrastinated worse than I did. When she cameout to the ranch, she also wanted to spend most ofher time on a horse moving livestock or feedingmineral. I already lack the discipline to do thefinancial planning and I hoped she would keepme on track, but it’s impossible if you both findreasons not to do it.”

Creating Financial Management SupportAfter the Sirolli workshop, I challenged the

Milton Ranch team (a ranch that I have consultedwith over 10 years) with this question: Are youtruly passionate at making the Milton Ranchprofitable? If so, then make me your ChiefFinancial Officer (CFO). As CFO, I would facilitatethe creation of the Milton Ranch Financial Planand ensure that the monthly monitoring,controlling and re-planning were completed.Dana Milton still paid the bills, but I would receivea monthly QuickBooks report and enter this dataonto the Milton Ranch Financial plan. Then Iwould make sure that we had a conference call orface-to-face meeting regarding any items that wereadverse to plan. Bill and Dana Milton report“[We] appreciate Roland’s steady, candid, andsometimes uncomfortable persistence when itcomes to financial management, because he won’tlet you be satisfied with a plan that doesn’t work.”Today, Dana has resumed doing most of thefinancial planning on the Milton Ranch. I stillparticipate in monthly control meeting/conferencecalls and facilitate the conversation about itemsadverse to plan.

I truly enjoy doing the financial planning andcrunching number with clients. In the last 10years I have engaged in the role of being a CFO fora handful of ranches. AS CFO, I demandaccountability and make sure the control happens,no excuses! I remind the team that if they trulywant to make their ranch profitable, they mustmake it happen. Since I have no vested interest inthe ranches I consult with, I cannot stop or make

them do something they don’t want to do.However, as CFO they know that I will hold them accountable for the decisions and actionsthey take.

A year ago, my wife, Brenda, assumed the roleof bookkeeper for the J Bar L Ranch. This ranchhad previously asked ranch personnel to completethis part-time job (pay bills; enter actual incomeand expenditures on QuickBooks program). Theemployees did not enjoy entering the data and didnot collect the needed information to make itaccurate. So, after losing its second in-housebookkeeper in less than two years, I suggested theycontract with Brenda for this service.

Bryan Ulring from J Bar L Ranch reports “It isreally nice to have the Kroos team workingtogether to fulfill our needs. Because Roland nowsour ranch operation very well, he has been

Brenda and Roland Kroos

Getting It Done—Building a Financial Management Teamby Roland Kroos

CONTINUED ON PAGE 17

In 1997, Holistic Management Internationalcame out with our first financial planningsoftware at the request of our network whowanted to continue to use holistic financial

planning process while wanting the benefits ofcomputer calculations. It functioned as a macrooff of Microsoft® Excel and mimicked the paperfinancial planning spreadsheet charts andworksheets. Over the years as Excel continued to beupdated, we updated the software.

We also received feedback over the years of whymany in our network used other software programslike Quicken or Quickbooks or created their own Excelspreadsheets. Ultimately, people were working on waysto address their budgeting, financial planning,financial management, and accounting needs.

Ultimately, realized profit is reinvested in either improved qualityof life or increased net worth or a

combination of the two.

Successful financial planning and managementcombines the best of human creativity andtechnology (software). Because each person orbusiness is unique, one software does not alwaysaddress everyone’s needs. Likewise, people approachholistic financial planning in different ways. Thebest software program won’t help you if you haven’tdone the thinking necessary for good financialplanning or don’t have ownership in the outcome.Moreover, if your recordkeeping or software feels liketoo much work, you are less likely to monitor. Thekey is to create a financial planning andmanagement system that works for you andaddresses the key steps in holistic financial planning.

Nine StepsIf you look at the graphic on page 17 you will see

the nine steps to financial success that CertifiedEducator Don Campbell talks about when he teacheshis classes. 1) The focus is always to look first at yourprogress toward your holisticgoal. If there is alogjam or adverse factors, you want to make sureyou are putting your money and/or energy therefirst. 2) The next step is to assess your current net

worth as a baseline for theyear. 3) Next you plan yourincome which includeslooking at currententerprises and consideringnew enterprises. That’swhere the gross profitanalysis comes into play.

4) Once you’vedetermined your income, you look at profit next tochallenge yourself to determine what you can setaside. Many people aren’t motivated to make profitjust to make profit. That’s why it is critical for peopleto understand that profit is invested in a number ofareas including: quality of life (logjams, adversefactors, etc.), the business (addressing weak links and increased net worth), or theenvironment (improving land health by buildingbiological capital which for some people is reallyabout quality of life). Ultimately, realized profit isreinvested in either improved quality of life orincreased net worth or a combination of the two.

5) After you have set aside a certain percentage ofyour income as your profit you will invest in avariety of investment areas, you need to determineweak links for each enterprise so you can determinehow much of your profit will go to addressing thoseweak links. 6) This information will then allow youto prioritize your expenses as wealth generating (logjam, adverse factors, weak links), inescapable (suchas debt), and maintenance.

7) When you look at yourplan to see if it cash flows, youcan then adjust when you arespending or bringing in incometo minimize need for credit ormaximize returns and play withthe market (see Don Campbell’sarticle that starts on page 5).

8) Last you look at how thisplan affects your net worth. If younet worth is less than before andyou feel fine about that givenyour holisticgoal and yourimproved quality of life, that’sgreat. It’s not about having themost money. It’s about knowingwhy you are making the decisionsyou are making and havingownership in the plan.

9) Any plan needs

Financial Planning Spreadsheet.

Holistic Management® Financial Planning—Human Creativity & Technologyby Ann Adams

a system for implementation and feedback. The plan,monitor, control, replan feedback loop in holisticfinancial planning is critical. This is where you needto create your own system that works for you. A plan isonly as good as your ability to implement, monitor,and adapt.

Simple or ComplexWhether your financial plan is simple (a

household with one salaried employee) or complex(a business with multiple enterprises includinglivestock), you need a way to create and monitor it.We created the new financial planning software withthat in mind. If you just want to have a quick way tocreate a budget or financial plan and an easy way toenter in your actual income and expense as ithappens throughout the year, the planning softwaremakes that easy with autofill features. Likewise, ifyou have a more complex business and want to runa variety of scenarios and explore different grossprofit analysis for different enterprises and have a

variety of products and assets thatyou want to track acrossdepartments, this software willalso perform those functionsalong with creating invoices andwriting checks.

The underlying factor in bothscenarios is that the decisionmakers are using the tools ofhuman creativity and technologyto improve their quality of life orincrease their net worth. Whetheryou use the old software or new, adifferent database drivenaccounting software, your owncomputer spreadsheet or HMI’spaper forms, stepping through thenine key steps to holistic financialplanning will move you towardyour holisticgoal—that’ssomething you can bank on.

Holistic Management®Financial Planning SoftwareThe key areas of the Annual Plan Spreadsheet area are:

FinancialsIncome/ExpenseLivestock WorksheetAssetsBank Accounts WorksheetSavings WorksheetLoan WorksheetProduction WorksheetGross Profit AnalysisProfit AllocationInvoicingAccount SetupReports

Number 129 � IN PRACTICE 7

8 IN PRACTICE � January / February 2010

A recent study in Rangeland Ecology &Management offers a resolution to this long-standing and puzzling inconsistency. The article,“Paddock size and stocking density affect spatialheterogeneity of grazing,” found that subdividinga landscape into paddocks and grazing them athigh stocking density for a short grazing periodwould change the distribution of forage utilizationacross that landscape. Paddocks representing 16-,32-, and 64-paddock rotations were more evenlygrazed than much larger deferred-rotationpaddocks.

Grazing distribution is uneven, especially inlarge paddocks on extensively managedrangelands, due in part to the inherent variationin the landscape, but also to differences in thepalatability of individual plants. Animals areattracted to previously grazed plants, leading to anuneven pattern of utilization where some patchesare grazed very heavily while adjacent areas arenot used at all. These patches can become centersof expanding rangeland degradation, even whenthe overall stocking rate and utilization are low,especially on arid and semiarid rangelands—hence the phrase “under-stocked yet overgrazed.”

With small paddocks, you can increase theproportion of plants that are grazed, and, withlong enough recovery periods, you can break thecycle of patch degradation. This improvement isnot automatic and requires adaptivemanagement.

Grazing periods should be short enough thatthe livestock are out of the pasture by the time re-growth occurs, and the non-grazing intervalshould be long enough that the plants haverecovered and can withstand another grazingbout. Thus the length of grazing and recoveryperiods should be determined by plant growthrates, and need to be lengthened during periods ofslow or no growth, when little or no recovery isoccurring—otherwise the result may not bedifferent from continuous grazing. In our study,we tried a second grazing period after aninsufficient recovery period, and the improveddistribution we had measured after the first

grazing period weakened. This implies aninteraction between the temporal and spatialdimensions of grazing management.

This may have occurred in previous grazingstudies where calendar-based schedules were rigidlyadhered to, and in the end there was no differencebetween grazing systems—because rotations werenot adapted to changing growth rates, sometimescausing overgrazing rather than preventing it. Theconclusion should be that rotational grazing doesnot work. Adaptive management, of course, is theessence of planned grazing.

Another reason why previous studies found nodifference between grazing systems was that all ofthe treatments were in very small paddocks, oftenwithin a single ecological site—including thecontinuous grazing treatment. “This is intended torepresent a large continuously grazed paddock,but what it really represents is a landscape ofmany small paddocks, each of which iscontinuously grazed,” said Ben Norton, a coauthorof the study. Thus, one of the signature benefits ofrotational grazing—paddock subdivision—wasincorporated into the continuous grazingtreatment. The results would be quite different atthe full landscape scale on a commercial ranch.

The study demonstrates that grazing should bemanaged in terms of spatial distribution as well asintensity (stocking rate), timing, and frequency.The spatial benefits of planned grazing may berealized through methods other than intensivefencing, including changing access to watersources, strategic supplementation, herding, and

manipulating animal behavior, including selectingor culling individual animals based on where theyforage. What really matters is the spatial andtemporal pattern of grazing as actually experiencedby the plants, and there are many ways, includingplanned grazing, to influence that.

Land managers have to deal with all variablesat once, and try to implement an optimumcombination to achieve a desired outcome.Scientists do essentially the opposite: hold allvariables constant except for one, to identify themechanisms by which nature works. Science couldtell you how a blanket was woven, by teasing apartthe strands; but would not illuminate the patternin all its complexity. The artist weaves the patternthat tells the story, giving the blanket its beauty,much as managers and animals create patterns onthe landscape.

This is the first study to quantify the beneficialeffect of planned grazing on livestock distribution.This leads to better land health and higher grazingcapacity, but this improvement depends on goodplanning and adaptive management. The articlerepresents an emerging scientific understanding ofgrazing ecology and management, based on aholistic view of complex, self-organizing systems ofsoil-plant-herbivore interactions, and adaptivemanagement of change on large and variablelandscapes. As such it is a beacon of hope forrestoration of the world’s grazing lands.

The paper is in the July 2008 issue ofRangeland Ecology & Management 61:380-388.It is available online at www.srmjournals.org,where it was one of the top five most viewed articlesof 2008.

Matt Barnes is a Certified Professional inRangeland Management in Kremmling, Colorado,whose holisticgoal recently led him to form ShiningHorizons Land Management, through which he isseeking a ranch to plan and manage. He can bereached at: [email protected].

The full citation for this information is: Barnes,M.K., B.E. Norton, M. Maeno, and J.C. Malechek.2008. Paddock size and stocking density affectspatial heterogeneity of grazing. RangelandEcology & Management 61:380-388.

http://www.srmjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-abstract&doi=10.2111%2F06-155.1

Improving Forage DistributionUtilization & Livestock Production—Planned Grazingby Matt Barnes

Progressive livestock producers around the world, including holistic managers, havesuccessfully improved both grazing land health and livestock production through variousforms of planned grazing, where paddocks are grazed briefly and then given time torecover. Until recently, however, grazing studies on research stations have generally failed

to find any advantage of planned over continuous or season-long grazing.

Study finds that intensive plannedgrazing can improve distribution,

offers resolution to longstanding discrepancy

pugging because of the moisture-laden clay-richsoils. Moving the herd frequently was an alternativeto feeding hay.

The tool of money and labor was used here aswell. On this farm there were two farmers, one whomilked the herd with an assistant. This allowed theother farmer to dedicate a larger portion of his timeto moving cows and maintaining ultra-high stockdensity. This high stock density laid down a litterlayer which feeds soil microbiology, ultimatelyincreasing the quality of the soil. Here the producerused primarily visual observation to determinegrazing moves and haying times.

On both farms visual checks of gut fill andgrass lengths were also used to determine movetiming and whether bale feeding was necessary. Thefocus for all farmers was that the grass had fullyrecovered so there would be no overgrazing.

Allowing for full plant recovery had positiveresults in both environments. Each producer wevisited managed differently in order to achieve theirown holisticgoal. Of all the tools outlined in HolisticManagement, grazing planning and animalimpact were the tools we have seen used mostfrequently. It was clear that regardless of how brittlethe environment of the farm was, keen planningand management benefited the farm on all levelsfrom soil to plant to animal.

Blake Hall has pursued learning about farming,including a trip to Judy Farms in Missouri where heattended his first Holistic Planned Grazing Class ledby Ian Mitchell-Innes. He completed his CarpentryApprenticeship in April 2009. Tina Windsor workedto promote sustainable living and global awarenessthroughout high school. Her undergraduate thesisresearched focused on the effects of climate changeon food and water security which led to a keeninterest in sustainable agriculture and local foodsystems. She completed her Bachelors in LandscapeArchitecture in December 2008. Tina and Blake canbe reached at: [email protected].

means to stretch the grass to follow the grazingplan. In this case the pastures needed to be grazedfor longer periods of time to ensure full recovery forthe rest of the farm without overgrazing. Thetechniques used were increased stock density,increased frequency of moves and supplementalfeed in the form of hay. Frequent moves separatedthe animals from where they had previously beengrazing, creating a physical barrier between themand the tempting second-bite.

Animal impact was used to lay-down litter tocreate a mulch layer of “armor” which maintainedsoil moisture during the heat of the day and acomfortable environment for soil micro-organisms.Tests with thermometers showed that soiltemperatures were up to 14 degrees F (8C) coolerwhere soil covered with mulch. In Vermont therewas much more biomass because of the moisture,which meant there was a thicker mulch layer. Thistool was clearly beneficial in both environments.

By allowing full grass recovery and movingcattle quickly at a higher stock density, the benefitsof avoiding the “second bite” after the grass planthad begun to re-grow were clear. The grass was tall,healthy and obviously had a very healthy rootsystem. Moreover, the cattle could eat relativelyselectively without creating favorable conditions forundesirable plant species.

Our two months in Vermont were spent on adairy. Tools used here were technology, grazingplanning, money, labor, and animal impact. Thetool of technology was in the form of sub-soiling.This particular technology was permitted by thehigh moisture levels, which allowed for more severesoil disruption because of quick soil and plantrecovery. We saw a test plot of sub-soiling while we were in Saskatchewan.The re-growth post sub-soiling wassignificantly more stunted than inVermont; however the farmer inSaskatchewan was hopeful that thebenefits will be clearer next season.This was a clear example of therecovery lag-time in more brittleenvironments.

Haying was incorporated intograzing planning if the grass gotahead of grazing. This also allowedfor the farmer to feed hay in the barn ifit rained for too many days and thepastures were getting too wet. Thedifficulty here, as opposed to inSaskatchewan, was in controlling

We’ve been interested in sustainableagriculture for quite some time andwhile Blake has been working oncompleting his Carpentry

Apprenticeship (finished last year), we’ve beenlearning all we could. While staying up-to-dateon innovative farming through reading theStockman Grassfarmer, Acres USA, and INPRACTICE, we worked part time on farms insouthwestern Ontario. Once Blake finished hisapprenticeship, we felt ready to hit the road andwork with innovative farmers and graziers tolearn enough to run our own successful operationin the future.

We have been on a trip across Canada and partsof the U.S. working on a number of farms, somewho practice Holistic Management, learning aboutgrass-based livestock. Our trip started in May withten days in New Jersey, spent two months inVermont and then moved westward across Canada.We spent August on two different farms insoutheastern Saskatchewan and were on a farm in northern Alberta.

Though we have learned much since we startedour trip, there has been one significant “A-HA!”moment: We witnessed similar tools being usedsuccessfully to manage land in both brittle andnon-brittle environments. These tools weremodified to suit the particular climate and goals ofeach farm, which provided us with a betterunderstanding of the effect that climate and soiltype has on re-growth and the importance ofallowing plants to fully recover.

It became clear that more-brittle environmentswould be more negatively affected by impropermanagement. A significant point was learning,through seeing, that overgrazing is a factor of timebecause it allows the “second bite” which results instunted re-growth of the plant. This is where we sawthe tool of grazing planning implemented.

In early August we moved from a non-brittleenvironment in Vermont to a more-brittleenvironment in southeastern Saskatchewan. Toolswe saw being used in Saskatchewan were: grazingplanning and animal impact. Our “A-HA!”moment occurred when we saw the differencebetween grass plant recovery times in Vermont (60days) and Saskatchewan (90 days).

It has been a very dry summer in southeasternSaskatchewan, particularly during peak growingtimes in June and July which resulted in stuntedgrass recovery. Graziers there noted this delayed re-growth through monitoring and took appropriate

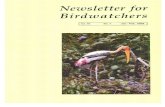

Learning From Two Environments—The Need for Plant Recoveryby Tina Windsor & Blake Hall

Blake Hall and Tina Windsor in Saskatchewan, Canada

Number 129 � IN PRACTICE 9

10 � January / February 2010Land & Livestock

Winter Bale Grazing—Feeding the Soilby Kelly Sidoryk

Our family has been involved in Holistic Management for over 20years. In that time our operation has moved from a custom feedlotto a forage-based, cow-calf/yearling outfit. At our Lloydminster site,we manage over 3,500 acres (1,400 ha), with about 1,000 deeded

and the balance rented. Our rental agreements are long term and withprivately owned land. The livestock numbers vary somewhat but there areusually 300-400 cows and approximately 700 yearlings. At theSaskatchewan location there is about 6,700 acres (2,680 ha), half leasedfrom the government. Cow numbers vary between 400 and 500. All theland is in forage. We try to focus on capturing and converting as muchsolar energy as possible. Our environmental conditions tend to besomewhat more non-brittle.

The operation is a family business founded by Dennis and Jean Wobeser,who are still active. Other members include son Brady and his wife, Shaunaand their two boys, Dalen and Nolan; and daughter Kelly Sidoryk and herhusband Mike and their children, Tess, Leah and Carter. Dennis, Brady andKelly are responsible for the day to day operations.

The FoundationOver the years we have realized the importance of the holisticgoal and the

various planning processes. Our holisticgoal is as follows:

Quality of LifeAs a family; growing, open, honest relationships are important. We value

a high level of trust with our family, friends and associates.We strive to be lifelong learners continuing the journey toward personal

growth and development. As well as being innovative leaders striving forwisdom and knowledge and the ability to share this with others.

We recognize the importance of respecting and working with nature.We strive for independence without relying on banks, professionals and

agri-business.We value freedom, independence and fun. The well-being of our

community is important.

Forms of ProductionWe wish to produce profit by harvesting growth on the land, converting

sunlight through livestock, based on renewable production.We wish to produce profit from the services we provide, in a manner not

conflicting with our values.We wish to produce an environment that promotes healthy relationships

and growth opportunities for all members.We strive to establish a positive working relationship with landowners

whose land maybe involved in our total operation as part of a joint venture.

Future Resource BaseWe believe in the importance of a healthy vibrant ecosystem; water cycle,

&

The darker green spots indicate where the bales were fed.

The top right hand corner shows the forage not impacted by bale grazing.The balance of the picture illustrates the lush, dark green color andincreased volume of plant material.

Number 129 � 11Land & Livestock

Gross profit analysis—does not apply as we were not comparingenterprises.

Energy/Money Source and Use—the energy used would be fossil fuelsbut would be a one time use only. Once the bales were set out the feed wouldnot be handled again mechanically versus all the fuel if we had done itourselves. Granted, the fuel was still being expended elsewhere. The source offinancing was partially solar dollars from previous profits and the balancewould be paper dollars from our operating loan through the bank.

Society and Culture—passed as we felt it would not have a negativeimpact. There was the issue however, of a new and untested feed method. Weexpected there to be negative feedback but didn’t think it would be enough todeter us, as we had been involved in Holistic Management for a number ofyears already we had received criticism because we did not fall intomainstream agriculture. So we felt we could handle it.

Giving It A GoIn 1996 we began moving out into the paddocks with winter-feeding.

Initially different combinations of straw and pellets were fed. Then in 2003on this particular paddock we began bale grazing hay. It has turned out to be better than we had hoped. Production has significantly increased, as hasbiodiversity.

Production in the form of ADAs has been a little more difficult to assess in our operation as we have been using some as stockpiled forage into thenext year.

The biological monitoring supports this improvement. We looked at themonitoring results on a particular paddock that had been bale grazed forthree winters over the last five years. Bare ground has decreased from around20% to virtually zero. The average distance between plants has gone fromover 3 inches to .6 inches. We now have a litter 3 category, which is a thicklayer of thatch where the bale butts were. This makes up 21% of the area. Theplants are predominantly grasses. More legumes and forbs for greaterdiversity would be desirable.

Some have questioned how much waste there is and if this will choke outor kill the grass. Our answer is we do not consider leftover hay to be waste asit becomes litter, which builds organic matter. The increase in productionand health of the grass plants more than makes up for the plants that maybe lost. Initially, there is a tremendous increase in growth in a circle aroundthe bale butt, which makes up for the mat in the center.

However, we have observed if the litter is initially quite thick there will bea delay in the grass growing through. Some have dealt with this byharrowing the bale butts, but one question that arises is the cost of runningthe equipment to do this. The bale butt is a large deposit of organic matter,which becomes a food source for micro-organisms. These in turn enhancethe availability of nutrients to the plants. The thick growth of the circles thencontinues expanding.

Others have also utilized this form of winter-feeding and done trialscomparing bale grazing to other types.

Don Campbell, from Meadow Lake, Saskatchewan, a fellow HolisticManagement® Certified Educator, estimates the increase in forageproduction from bale grazing to be two to four times in the next growingseason.

Cost/Benefit AnalysisSteve Kenyon ranches in the Barrhead area of northern Alberta and also

has experience with bale grazing. “Bale grazing allows us to greatly reducelabor and equipment requirements during the feeding period. Last seasonwith a four-five day graze, feeding labor worked out to under $.10/hd/day.Total feed and labor costs were under $1.15/hd/day. In addition to the

mineral cycle, and energy flow; which emphasises complexity. Our landscapewill be at a level of succession mostly comprised of grasslands along withnatural bluffs, wetlands, water sources and a diverse community of wildlife,birds, insects and micro-organisms.

Moving CowsWe have been practicing planned grazing for many years. The grazing

cells are subdivided into paddocks with electric wire. We were one of thosewho spent a lot of time on fencing after first being introduced to HolisticManagement. Along with this we have been doing grazing plans to ensureadequate recovery time of plants. Initially our recovery times were not longenough and we have extended these.

The weak link in our operation has been resource conversion. We werenot growing as much forage as we could. There was more bare ground thanwe would have liked. In our winter climate, one of the biggest expenses iswinter feed. We wanted to extend our grazing season and simplify the winter-feeding. That meant handling the feed as little as possible. As we hadchanged the operation, we had gotten rid of most of the feed producingequipment and our calculations showed it was cheaper to buy the feed thanmake it.

One of our guiding principles was to make the cows do most of the work.The idea of setting hay bales out in the paddocks in the winter and movingthe cows regularly started to make more sense. In effect we would be movingthe cows in the non-growing season similar to how they were in the growingseason. We had encountered some that were doing it with straw as asupplement.

Testing StrawWhen running this idea through the testing guidelines this is what we

came up with: Cause and effect—the issue of too much bare ground could have been

caused by lack of nutrients due to previous farming practices. The addition oforganic matter through bale grazing and the associated animal impact willhelp increase organic matter and the health of the soil and, therefore, theplants. It is also important to ensure that plant recovery times are adequatethrough our planned grazing during the growing season.

Sustainability—passed as it was taking us toward more complexity inour ecosystem as described in our future resource base.

Weak link—passed as our weak link was resource conversion andcovering more bare ground, we felt would increase forage growth.

Marginal reaction—this did give us the best return on money invested.The least investment was required with the greatest return as compared totraditional daily feeding where one had to process and handle the feed (withlabor, equipment and fuel) to take it to the animals as opposed to theanimals getting it themselves.

Cows bale grazing in the winter.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 16

12 � January / February 2010Land & Livestock

Bringing Carbon Back to Agriculture—A Bedded Pack Management Systemby John M. Thurgood

Five miles outside of Arkville, New York, deep in the Catskill Mountains,on a farm with steep, productive pastures and meadows, Jake and KarenFairbairn were managing a mixed herd of 35 dairy cows. The cows weregrazed during the six-month growing season and were out-wintered

using a pack of straw for loafing and resting. They were fed large round balesof hay in an area adjacent to the pack. Jake had remodeled a beautiful tie-stall dairy barn to accommodate a five-unit swing parlor. The cows werehealthy, as evidenced by low bacteria counts in their milk. Jake related, “Myherd had the lowest somatic cell count for the county (Delaware 2005). “Thechallenge was runoff from the pack and feeding area moving to a nearby roadditch, then a stream. In addition, the fields used for manure spreading wereinaccessible during most of the winter due to icing of farm lanes and asnowpack on fields.

The Fairbairns decided to enroll in the Watershed Agricultural Program ofthe Watershed Agricultural Council (WAC). In the New York City Watershed,whole farm planning is being done on nearly every farm with significantnumbers of livestock to protect the water supply for 9 million water consumersthat reside in and around New York City. The voluntary program is led by acouncil of farmers and is fully funded by the New York City Department ofEnvironmental Conservation, federal agencies and other sources.

Whole farm environmental planning and implementation is done by ateam of professionals with the participating farmer as an equal member. TheFairbairns’ team included Dan Flaherty, WAC Small Farm ProgramCoordinator, and Civil Engineering Technicians Chris Creeelman and PaulaChristman Bagley, of the Delaware County Soil and Water Conservation Districtand the WAC respectively.

The traditional way to store winter manure in the Northeast is in liquidform using a tank or lagoon. The team wanted to explore other alternativesdue to the negative aspects of liquid manure: odors, the instability of nitrogen,the need for specialized equipment to transfer, transport and apply, and thehorsepower needed to perform these functions.

Jake and Karen didn’t want to have their cattle confined to a concretebarnyard and had concerns with the associated water management system.Effluent from rainfall hitting the barnyard would need to be treated using avegetative filter area. In the Fairbairns’ case, barnyard rainfall would be pumpedup a steep hill to the filter area. The energy needed to pump this effluent and theassociated maintenance didn’t seem to be a wise use of resources.

Thinking Outside the BoxIt soon became apparent to the team that an “outside of the box”

solution was needed. They learned about a new approach being used innorthern Vermont. The team and a delegation from the WatershedAgricultural Program visited numerous farms, including Jack and AnnLazor’s Butterworks Farm, where the organic herd of 45 dairy cows is housedin a bedded-pack barn. Jack does not stir the bedding, just adds new layers ofstraw daily to cover manure deposited the previous day. Dan and Jake wereimpressed with how clean and content the cattle were on the bedded pack—the cows were down-right happy! In addition to housing the cattle, Jackbelieves the pack is a major benefit to his farm system as a valuable source of carbon to be returned to the soil.

Jack expressed concerned that we have “de-carbonized” agriculture inAmerica. He expects the composted pack to benefit the soil biologicalcommunity, increase soil organic matter, and enhance soil health. Increased soil organic matter also carries the benefit of sequestering carbonfrom the atmosphere.

After the visit, the team was convinced that a bedded-pack barn was the best solution for the Fairbairn farm, and planning began in earnest. A Natural Resources Conservation Service Conservation Innovation Grantwould fund construction as well as a labor and economic case study of the bedded-pack project. To differentiate the system from composting barn technology, the team coined the term “Bedded Pack ManagementSystem (BPMS).”

The Fairbairn facility was designed to house a 50-cow milking herd forsix months, approximately mid-November to mid-May, depending on theweather. The farm’s average weight per cow was 1,000 pounds (450 kg). Thefacility was constructed as a natural wood-sided structure with a steel-framed,fabric-covered, roof structure. The walls are composed of rough cuttamarack planks that were nailed and lagged to rough cut locust posts.

A great source of design information for bedded pack barns is “Penn StateHousing Plans for Milking and Special-Needs Cows” (NRAES-200) whichcalls for a bedded pack area of 125-150 square feet (14-17 sq m) per dairycow, along with a feed alley. The Fairbairn facility did not include a feedalley, as manure scraped from a feed alley is in liquid form requiring astorage tank. Manure accumulation was estimated using figures from the“Livestock Waste Facilities Handbook,” Midwest Plan Service-18. The cowswere fed using round bale feeders. When designing a structure, space toaccommodate the feeders and waterers needs to be accounted for.

Two waterers were installed, one on the sidewall and one in the center ofthe building. As the pack rose, cribbing was added to raise the waterers.Exterior of the Bedded Pack Management System

Interior of the Bedded Pack Management System

Number 129 � 13Land & Livestock

Adjusting the SystemThe first two years the Fairbairns housed animals in the BPMS they used

an average of 3,200 pounds (1,440 kg) of straw per 1,000 pounds (450 kg) ofanimal. The first year they housed cows and heifers and the second onlycows. Jake added bedding to the pack every other day using a rear dischargemanure spreader. Maneuvering the spreader, Jake was able to bed the facilitymechanically, without having to manually pitch the bedding.

The pack was removed from the facility using a skid steer with a grappleattachment. With significant dust, good ventilation proved to be important.Processed straw makes removing the pack much easier. There were odorswhen emptying the pack, but they dissipated quickly and there were nocomplaints from neighbors. The pack was loaded into a flail manurespreader and windrowed for composting.

Three samples of the pack were taken from the BPMS and analyzed by thePennsylvania State University Agricultural Analytical Services Laboratory. Thebulk density and carbon-to-nitrogen level of the material proved to be wellsuited for composting (On-Farm Composting Handbook, NRAES 54). Themoisture level of 70% was higher than a more optimum 60%, but this couldbe managed by turning the windrows. It is important to note that little to nocomposting activity occurred in the pack. This was as expected; the packdoesn’t provide enough air for composting to take place.

Results and RecommendationsThe Bedded Pack Management System proved to be an excellent

environment for the cows as evidenced by continued outstanding milkquality performance and an increase of 2,000 pounds (900 kg) per year inherd average milk production due at least in part to the BPMS.

On the whole, there were no large labor saving advantages of the BPMSon the Fairbairn farm as the Fairbairns had a labor efficient swing parlorand out-wintered their cattle before the BPMS was implemented. Farms thathave labor intensive tie-stall barns and facilities with a substandardenvironment for dairy cattle might reap more benefits.

The large amount of bedding required by the BPMS indicate that limitingthe use of the facility to half of the year during the inclement months, thenkeeping animals on pasture, is necessary to make bedding costs manageable.It is expected that bedding costs will also make this an unattractive option forbeef farmers that have extremely tight profit margins.

Reducing bedding cost is important for the BPMS to be sustainable.Farms that produce small grains and associated straw will be able to reducebedding costs since they won’t have to pay for transport. Producing andcycling straw/carbon on the farm avoids the accumulations of importednutrients from purchased straw. For farms that don’t raise annual cerealcrops, the harvest of mature hay, such as Reed Canarygrass, might be a viable option.

Organic farms that place a higher value on compost, due to the relativelyhigh cost of organic fertilizers and their increased emphasis on soil health,will be better able to justify the additional cost of bedding material. There isa trend of organic dairy farms to produce small grains to feed their cattle toreduce purchased feed costs and to better cycle nutrients on the farm. Inaddition to providing nutrients for cattle, the small grains can also supply thebedding needs of the animals.

Another option to reduce bedding costs would be a BPMS design toinclude a concrete feed alley, thereby reducing the amount of manuredeposited on the pack since livestock excrete significant amounts of manurewhile eating and drinking. The downside is that manure removed from thefeed alley may need liquid storage. The capital expense of implementing asolid and liquid system might be economically prohibitive.

Farms with significant herd health issues transferrable between animals,especially through their manure, might not want to implement the BPMS

since the animals are fed on the pack. Raising the round bale feeder abovethe pack or using a feed alley will reduce this risk.

Finally, the bedded pack may eliminate, or significantly reduce, the hoofand leg problems associated with housing dairy cattle on concrete or otherhard surfaces. Animal longevity and productivity should provide economicgains not quantified due to the limitations of the case study.

The Fairbairns were very happy with their three years using Bedded PackManagement System. Last year, they made a career decision for Karen toutilize her talent and love of managing a summer camp enrichmentprogram, accepting a position at a camp in Connecticut. The camp includesa model farmthat Jake takesgreat satisfactionin managing.Jake and Karen’sparents are nowraising heifers inthe facility.

The decisionto implement aBPMS has verylargeimplications.Farmersconsideringsuch a systemshould evaluate how it fits withtheir resources and management philosophy. Complete information andrecommendations on the BPMS can be found in “Bedded Pack Management System Case Study,” John M. Thurgood, Bagley P. C., Comer C.M., Flaherty D.J., Karszes J., Kiraly M., Department of Applied Economics and Management, College of Agriculture and LifeSciences, Cornell University, EB 2009-16, September 2009. If you areconsidering a BPMS, you will certainly benefit from this resource. You can obtain a copy at this web address:http://aem.cornell.edu/outreach/extensionpdf/2009/Cornell_AEM_eb0916.pdf

John Thurgood is a Holistic Management® Certified Educator, HolisticManagement International, and Watershed Agricultural Extension TeamLeader for Cornell Cooperative Extension in Delaware County as part of theWatershed Agricultural Program. He can be reached at: [email protected].

Jake bringing a large round hay bale into BPMS

Jake and Karen Fairbairn

14 � January / February 2010Land & Livestock

When my granddad homesteaded here near San Jon, NewMexico in 1907 his dream was to farm. He owned the firstInternational Harvester Dealership in east central NewMexico. My dad has many stories of him and his older

brother picking up horses from farmers who had traded them in on anew tractor. I grew up listening to stories of them meeting the train inHereford, Texas and driving the tractors back home. We still have acombine from granddad’s implement dealership and another that daddrove home from Hereford. My mom and dad did custom wheat andmilo harvesting for a number of years; one of the old combines proudlybears a sticker of when it was in the “Million Acre Harvest” to help feedthe troops in WWII. Needless to say farming is in our blood.

There have been many tough decisions to make over the past 100 years.In the mid ‘90s my parents had to make a decision that could, and inessence did, change the face of our family homestead. They enrolled ourcropland into the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). The programadministered through the Farm Service Agency (FSA) paid farmers to takehighly erodible acres out of farm production and plant those acres to grass.The land was then to sit idle for 10 years. We have taken advantage of twoCRP programs and one extension, meaning some of our farm land has notseen a plow for over 22 years.

Cropping versus PastureAttitudes have changed dramatically since the first CRP enrollment. I

remember my parents spending long hours discussing whether to enroll ornot. Everyone was talking about it: Who was going to sign up? What werethe requirements? Where would you get a grass drill? Who was selling grassseed? But the number one comment was: “We will sign up for 10 years andthen break it out again.” That was my parents’ conclusion also. So when itcame time to plant grass, they chose the cheapest grass seed because therewas no intention of leaving it in pasture. They enrolled only a portion ofour farm so that we could still have wheat pasture and hay production forthe cattle.

In that ten-year period we made some hay, but had no wheat pasture.When we cut our last wheat crop, Dad and I went to town to sell the grain.Briefly figuring our expenses and anticipated income we concluded we hadnot even paid for our fuel or our time. So when the second CRP programwas announced, we quickly decided to enroll all our acres! By this time itwas pretty well established our farming days were over so we planted abetter mix of native grasses and forbs with grazing in mind. After the grasswas planted we took our prized 3588 International Harvester to a farm saleand watched another proud farmer leave with his new to him tractor. Weknew it was the end of an era.

Twenty some odd years ago our community and family was abuzz withwhether or not to enroll acres into the CRP program. Today the buzz isabout what to do with it now that it is coming out. With nearly 31 millionacres generating $1.7 billion nationwide, I know we are not alone in thisdilemma. Our CRP sits in Curry County in east central New Mexico. Weenjoy on average 16 inches (400 mm) of rain a year with six months offrost-free days. The only weather event we can count on is the wind; it’sgoing to blow; it’s just a matter of how hard.

Dad and I have known the CRP grass would enable us to increase ourcow herd and add flexibility to our grazing plans on our native grasspastures. For the past several years we have taken advantage of the

To CRP or Notby Kelly Boney