1174 Sapirstein Suppl

-

Upload

valentinonizzo -

Category

Documents

-

view

239 -

download

0

Transcript of 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

-

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

1/47

OPEN ACCESS: APPENDICES www.ajaonline.orgAJA

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

DOI:10.3

764/ajaonline1174.Sapirstein.suppl

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

Appendix 1: Methodology

ASSUMPTIONS

This study of the productivity of Attic vase paintersbegins with three underlying assumptions. First, the at-tributions made by Beazley and other scholars are in largepart reliable, although permitting a degree of uncertaintyand occasional mistakes. Second, the chronological frame-work for Attic vases is accurate enough for individualcareer lengths to be estimated within several years of thereality. Third, the collection of vases studied by Beazleyand his successors is a relatively unbiased sample of thetotal Attic pottery production from the sixth and fifthcenturies B.C.E. The results of this study suggest thatthese assumptions are not problematic.

On the first assumption, the validity of attribution as

a process is supported by the facts that more than 40 ofthe most prolific painters produced 710 works per yearand that many of the less productive hands belonged topotters. Despite past criticism of the method of attribu-tion, it is difficult to imagine how these results could have

been attained if the hands examined here were artificialconstructs. If attribution were an arbitrary process, eachidentity would have a random number of works. Whilethis reasoning might sound circular, the confirmation isactually from two independent sources: the lists of attri-

butions and the time span over which these works wereproduced. Since the chronology has been determined

by external evidencesuch as archaeological contexts,broader stylistic developments, and parallels with other

artswe can say that the chronology generally confirmsthe number of attributions for each hand.

This confirmation applies only to the well-definedhands. The results of this study emphasize that Beazleytended to overdivide the vases whose authorship is

unclear.1

The methodology of attribution begins with eachside of an Attic vase potentially mapping to a differentpainterso, for example, 40,000 vases could equal 80,000painters. Identifying unique stylistic features connectsmultiple works to an artisanal identity. The linkageswithin the works of the major painters are well defined,

but Beazleys work was far from complete. The uncer-tainty in the linkages for the bulk of the Attic material isevident in the hundreds of minor painters and groups,many of whom were followers or in the circle of aprolific hand. New relationships may be demonstratedwith future study, but most of these minor hands willprobably remain ambiguous. Beazley also lumped to-gether many low-quality vases, such as more than 1,000

in the manner of the Haimon Painter, which are unlikelyever to be sorted into individual hands. As a result, minorpainters have been excluded from this study because wehave little reason to believe that any of these designationsactually correspond to one artisan.

As for the second assumption of this study, the internalchronological framework for Attic vase painting cannot

be tested by comparison with the number of attributions.However, it is of interest that there are no periods whenaverage productivity markedly rises or drops for specialistpainters. When working full-time, Attic painters appearto have decorated about the same number of vases eachyear throughout the 125-year period when specialists werepainting in the black-figure and red-figure techniques.

There must have been differences for specialists in sometypes, such as Little Master cups, but as a whole the

1 Beazley employed a Morellian technique to identify individual hands of anonymous painters, describing the method insome detail in two articles (Beazley 1922, 1927) defining the characteristics of the Berlin and Antimenes Painters; see also Kurtz1985; von Bothmer 1985a, 13; Turner 1996, 267. Scholars of the following generations have defended his methods validity andarticulated in detail the characteristics of many painters, especially in response to the controversial hypotheses of Gill and Vick-ers (Robertson 1976, 29, 3240; 1985, 19, 257; 1992, 45; Gill 1988a, 1988b, 1991; Gill and Vickers 1990, 1995; Vickers and Gill 1994,859; Williams 1996; Neer 1997, 1625, 256; Whitley 1997; Oakley 1998; 1999; 2004a, 6971; 2009, 6056; Rouet 1999; Boardman2001, 12838). Beazley certainly was fallible, but only a small portion of his attributions have been vacated. Most debate has con-centrated on pieces about whose attribution Beazley himself was unsure.

Methodology, Bibliography, and Commentary for thePainters in the StudyTwo appendices to Painters, Potters, and the Scale of the Attic Vase-Painting Industry,by Philip Sapirstein (AJA117 [2013] 493510).

Print figures and print table 1 cited herein refer to figures and the table in theAJAprint-published article.

http://www.ajaonline.org/http://www.ajaonline.org/article/1649http://www.ajaonline.org/article/1649http://www.ajaonline.org/article/1649http://www.ajaonline.org/ -

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

2/47

2

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

P.Sapirstein,Methodology,B

ibliography,andCommentaryforthePaintersintheStudy

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

industry turned out a relatively consistent productregardless of technique. The only chronologicaladjustments that might be warranted are in thecareers of individual artisans.2

On the third assumption, the collection of about40,000 published vases and sherds appears to be

relatively unbiased. Beazley attempted to cata-logue all vases and fragments, regardless of theirquality. Most attributed Attic vases are held by mu-seums, especially those vases in Beazleys lists andthe CVAseries, with the result that relatively fewof the attributed finds are from recent documentedexcavations. Pots from graves are certainly betterrepresented than pots from any other type of con-text, because they tend to be better preserved andare more attractive to purchasers. The collection isa subset of the whole body of Attic material, lessthan half, but it is a sizeable fraction of the vasesthat can be attributed at all.3Statistically, it is a verylarge sample, and it is unlikely that the relative

proportions of attributions by each painter in thisstudy would change much even if we had reliableattributions for all known vases and sherds. OnlyMakron stands out as potentially overrepresented

because of the special attention of one collector.

TALLYINGSYSTEM

The study depends on a consistent method forcounting attributions and estimating career datesfor each artisan. All painters with more than 150possible attributions are included in the study, asare the best-studied individuals with fewer than150 attributions.

Most of the vases in this study were identified

by Beazley himself. However, monographs anddissertations from the past 40 years have refinedthe attributions for many individual painters andgroups and in most cases supersede Beazleys lists.All other things being equal, a study of an Atticpainter published in 2005 will inevitably havemore catalogued works than will a similar studyfrom 1975. To level the discrepancies from the timeof publication, attributions through 2011 have beenincluded in this study. The richest sources are

recent museum catalogues of vases, especially theCVA. Final excavation volumes contain relativelyfew new attributions and are dominated by thepottery catalogues from the Athenian Agora andthe Kerameikos. Because the quantity of materialis overwhelming, and some of the newer attribu-

tions are disputed, the tallies analyzed here areonly approximations.

Almost every painter has some associatedworks whose authorship is uncertain. Beazleyused a variety of phrases to designate uncertainty,such as near or in the manner of a particularpainter, group, or vase. He never wrote a completeglossary, and it became apparent during the com-pilation of this study that he did not always applyhis terminology consistently. For the purposes ofthis project, the various shades of meaning areless important than whether Beazley thoughtthe vase might be from the hand of the painterhimself. Generally these are the works listed as

near a painter, which Beazley appended to themain list of attributions. The near works have

been tallied as uncertain attributions here, withsome exceptions.4

Many of Beazleys other categories of relation-ship, such as related to or manner of, implythat a vase was painted by a different artisan. Ofthe vases falling under the category manner of,Beazley writes:5

[T]he list may include (1) vases which are likethe painters work, but can safely be said notto be from his hand, (2) vases which are like thepainters work, but about which I do not know

enough to say that they are not from his hand,(3) vases which are like the painters work, but ofwhich, although I know them well, I cannot saywhether they are from his hand or not. SometimesI make the situation clear, but more often I do not.

In this study, a vase in the manner of a painterhas been tallied as an uncertain attribution onlyin the rare cases where Beazley wrote that it fellinto his second or third category. Vases in the firstcategory have not been counted.

2Rotroff (2009) recently down-dated the introduc-

tion of red-figure to ca. 520 B.C.E. through the analy-sis of the Athenian Agora contexts, bringing theattribution rates for Oltos and the first three phasesof Epiktetos career in line with the rest of the special-ist painters. If Oltos and Epiktetos had started at 525B.C.E., as in the conventional chronology, their attri-

bution rates would be slightly below the norm.3 Beazley catalogued ca. 34,000 vases and frag-

ments, whereas a recent search of the Beazley archive(www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/xdb/ASP/default.asp)returned almost 80,000 records. The new material isdominated numerically by the recent publication oflarge quantities of context material from excavations.The total numbers of Attic sherds are even higher

(Scheibler 1983, 9; Stissi 2002, 2433). Because the

greater part of this new material has not been attribut-ed and there is a high potential for preservation bias,it has been largely excluded from this study. The at-tribution rate (a function of the recovery ratio) for allpainters would rise if all the tens of thousands of ad-ditional fragments could be fully attributed.

4 Beazley Addenda2, xviiixix. Throughout his cata-logues, Beazley uses near to designate the worksthat he thought but could not be sure belonged tothe painter. However, he occasionally used the wordnear to compare separate hands, so near worksthat Beazley clearly believed were by another artisanhave been excluded here.

5ABV, x; Paralipomena, xviiixix.

-

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

3/47

3

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

P.Sapirstein,Methodology,B

ibliography,andCommentaryforthePaintersintheStudy

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

Several painters in this study have been af-fected by the lack of clarity surrounding worksclassified in their manner. The chapter on Lydosincludes numerous sherds that Beazley was unableto attribute specifically but that may have belongedto Lydos himself, his companion the Painter of

Louvre F6, or their minor associates. As a result,these two major hands are probably undercountedin this study relative to more distinctive hands.6

Beazley left the Antiphon, Beldam, Emporion, andTarquinia Painters all with relatively long man-ner lists or other problematic attributions, and thesituation is similar with the recent monographs onthe Griffin-Bird, Red-Line, and Niobid Painters.These painters have relatively low attributionrates, ranging from 5.2 to 7.1. The Antiphon Painterwould almost certainly have been as productive asa typical specialist if some of the 126 undifferenti-ated works in his manner could be demonstratedas his own.7 The low rates of any of these painters

could be due to the problem of identifying theirworks.8 Nonetheless, a high proportion of man-ner attributions does not guarantee that a painterhas been undercounted.

PRESERVATIONBIAS

Despite the assumption that most of the tensof thousands of Attic vases now in museums area randomized, largely unbiased sample of theproduction of individual painters, there are severalexceptional contexts that appear to have a muchhigher preservation rate than that of other Atticvases. Although these sherds make up a smallpercentage of the total, they have introduced

a significant preservation bias into the corpusfor several painters in this study. Most are fromAthens, and there is at least one unusually richcontext in Thasos.

Athens, Kerameikos DepositsThe foremost example is the collection of

more than 160 sherds purchased by the FriedrichSchiller University of Jena in the 1850s. Traced toexcavations at Hermes Street near the Keramei-

kos, the deposit has been interpreted as a stock ofvases ready for sale.9 This single deposit from ca.400 B.C.E. contains more than half of the knownworks by the Jena Painteronly a few dozen ofhis vases come from outside Hermes Street. Thealmost 100 works from the Hermes Street deposit

make the Jena Painters corpus statistically unlikethat of most Attic painters, whose lists have beenassembled from dozens or hundreds of differentcontexts with no more than a few vases in each.Consequently, any collection of material with ahigh concentration of figured potteryin par-ticular, numerous works in a single handmust

be excluded or adjusted.There are two other contexts from Athens that

appear to come from concentrated debris of work-shops or pottery merchants. Most of another as-semblage excavated at the Thission metro station inAthens, near the Kerameikos, was purchased in theearly 1900s by the University of Bonn museum.10

The collection of more than 460 sherds includesmisfires, and the deposit is interpreted as discardsfrom one or more kiln firings between ca. 420 and400 B.C.E., although there is also a small quantityof earlier material. The Painter of the Athens Dinosis dominant, with fragments from at least 50 vases,yet he has only two attributions from outside thislarge deposit. Consequently, he and the Jena Painterhave been excluded from this study. Both appearto have been relatively minor figures whose worksare much better preserved through accidental dis-covery than those of most other Attic painters. Thethird concentrated deposit is at Marathon Street 2.11

Although it includes several sherds by the Brygos

Painter, it is a minor percentage of his corpus andhas not been treated specially in this study.

Athens, Sanctuary of NympheThe Sanctuary of Nymphe, to the south of

the Acropolis, may be the richest context of At-tic figured vases yet excavated. Hundreds ofthousands of sherds, including large numbers ofnuptial loutrophoroi, are reported from the 1950sexcavations of the unusual deposit.12 Hundreds

6See the commentary in appx. 2 on these painters.7

Because the works in his manner outnumber theattributions to the Antiphon Painter himself, he hasbeen treated as a statistical outlier.

8Although the group of 61 vases in the manner ofthe Niobid Painter is the second largest in proportionto the painters regular attributions, his low attribu-tion rate can be explained by his activity as a potter.

9ARV2, 151021, 1697, 1704;Paralipomena499501;Oakley 1992, 19697; Paul-Zinserling 1994; Geyer1996, 1, 534; Monaco 2000, 628, 2016; Kathariou2002, 24060; 2009; Tugusheva 2009; Bentz et al. 2010,113, 12849.

10 Oakley 1992; Monaco 2000, 5962, 195201;Bentz et al. 2010, 129, 150204. Oakley (1992) cites this

example as reason to doubt studies of the preserva-

tion rate of Attic pottery as a whole, although this andthe Jena material are clearly exceptional.11Maffre 1972, 1982, 1984, 2001; Monaco 2000, 82

5, 21112. More than 200 fragments were excavatedat the outskirts of the Kerameikos, of which ca. 10%are cups painted by the Brygos Painter and his circle.The Brygos Painter has six attributions; removingthem would reduce his attribution rate to 9.3 from 9.5works per year (see appx. 2). Myson, Onesimos, andthe Triptolemos Painter each have one attribution.

12Orlandos 1955, 1112; 1957, 912; Miliadis 1955,512; 1957; Oikonomides 1964, 1617, 227, 48; Trav-los 1971, 361; Papadopoulou-Kanellopoulou 1972;1997, esp. 15, 215; Tsoni-Kyrkou 1988.

-

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

4/47

4

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

P.Sapirstein,Methodology,B

ibliography,andCommentaryforthePaintersintheStudy

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

of the fragments have been attributed by Beazleyand later scholars. The Washing Painter is the bestrepresented, with at least 230 secure and 21 uncer-tain attributions from the sanctuary. The GorgonPainter, the Polos Painter, Lydos, the Painter ofLouvre F6, the Theseus Painter, the Pan Painter,

Hermonax, and the Sabouroff Painter also haverelatively high numbers of attributed fragmentsfrom here (see print fig. 1).13 Unfortunately, thepublication of the material is incomplete, par-ticularly the more numerous red-figure fragments.Although a monograph on the sanctuarys black-figure material was recently published, Fritzilassubsequently catalogued 86 new black-figureattributions for the Theseus Painter.14

The circumstances of the find at the Sanctu-ary of Nymphe are unique. The major survivinginstallation is an Early Classical elliptical periboloswall, 10.5 x 12.5 m, over an older altar; both weredisrupted by Roman houses that must have re-

moved much of the earlier deposit.15 The sherdswere concentrated in layers up to 1 m thick insidethe peribolos and up to twice as thick outside itswalls. Finds were chronologically mixed withinthe deposit, ranging from the seventh to late thirdcenturies B.C.E.16

The rich deposit is most problematic forthe Washing Painter, whose roughly 250 frag-ments from this single context outnumber theapproximately 200 pieces by him from all otherplaces. His attribution rate excluding this contextis below seven works per year but jumps to morethan 15 attributions per year when the context isincluded. To look at the problem another way, if

these 250 fragments represented only 1% of theoriginal number of Washing Painter loutrophoroiat the Sanctuary of Nymphe, the Washing Painterwould have had about 25,000 of the vases at thissite aloneand twice as many if the recovery ratiowere closer to 0.5%. Including the loutrophoroi byother painters, the original numbers implied by a1% recovery ratio might be in the millions.

Obviously, the 0.51.0% recovery ratio does notapply to this particular context. Unfortunately, it isimpossible to develop a reliable estimate for howmany actual loutrophoroi are represented by thismass of fragments at the Sanctuary of Nymphe.

Many thousands of vases could have been dedi-cated during the 180 years between the time of theGorgon and Washing Painters, and the loutropho-roi must have been periodically smashed and thefragments packed into the peribolos to make roomfor new dedications by Athenian brides. While

it is tempting to exclude the deposits from thisstudy altogether, this would introduce a significant

bias against the nine painters who, owing to thefortuitous discovery of this sanctuary, are knownto have decorated many of these nuptial vases.

To reconcile the Sanctuary of Nymphe withother places, only 20% of the attributed fragmentshave been counted in this study, as if the recov-ery ratio were five times the norm.17 Althougharbitrary, this adjustment reconciles the fact thatthe deposit is incomplete and thus may be only afraction of the total number of vases dedicated atthe sanctuary. It is still richer than most contextswith Attic vases. With this compromise, during

his three decades the Washing Painter would stillhave decorated the equivalent of 5,00010,000loutrophoroi. If distributed evenly throughout hiscareer, he would have painted on average about200400 loutrophoroi per year, whereas the The-seus Painter, the second most prolific painter of thetype, would have decorated about 50100 per year.The 20% adjustment is a necessary compromiseif the loutrophoros painters are to be included inthe study at all, and it brings the attribution ratesfor the Washing and Theseus Painters in line withthose of other painters.

It is important to point out that most Atticpainters have no loutrophoroi from the Sanctuary

of Nymphe (fig. 1). Consequently, the exclusionof the nine painters who did decorate the typewould have no significant effect on the results ofthis study. Only the Theseus and Washing Paint-ers have very large numbers of sherds from thesanctuary.

Athens, Acropolis

The second place that requires special treat-ment is the Acropolis itself. Although many ofthe attributions from the early excavations do nothave specific context records, the deposits fromthe Persian sack of 480 B.C.E. and the subsequent

13www.ajaonline.org/article/1649; see also appx. 2on these painters. Beazley (Paralipomena, xvii) was thefirst to attribute many fragments from the sanctuary.

14The catalogue by Papadopoulou-Kanellopoulou(1997, 19396, 2001) includes only four fragments byor near the Theseus Painter. See appx. 2 on the newattributions in Fritzilas 2006.

15See the accounts in Miliadis 1957; Travlos 1971,361. Because of the later disruptions, the archaicsherds from outside the main sanctuary deposit are

assumed to have originated from the sanctuary layers(Papadopoulou-Kanellopoulou 1972, 18587).

16Miliadis 1957, 26; Orlandos 1957, 11; Papado-poulou-Kanellopoulou 1972, 18587; Tsoni-Kyrkou1988, 225.

17For all the calculations, 20% of the attributions toa painter from the sanctuary are counted in his careertally, and all fractional values are rounded up. Thus, apainter with one or two sherds from the sanctuary isstill given one attribution.

-

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

5/47

5

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

P.Sapirstein,Methodology,B

ibliography,andCommentaryforthePaintersintheStudy

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

renovations appear to have contained the pre-ponderance.18 Figure 1 shows that all the best-represented painters from the Athenian Acropoliswere active by the time of the sack. The EuergidesPainter, the Theseus Painter, Makron, and the Eu-charides Painter each have at least 30 attributions

from the Acropolis, while the Polos Painter, Lydos,the Berlin Painter, the Kleophrades Painter, theBrygos Painter, and Syriskos each have at least 10.In contrast, more than half of the painters whosecareers began after the Persian sack have no frag-ments identified from the Acropolis, and only thePan and Calliope Painters have more than 10 at-tributions.19Among the painters considered in thisstudy, those active in the Archaic period have eighttimes as many fragments from the Acropolis as dopainters active in the Classical period.

These data indicate that the recovery ratiofor vases dedicated on the archaic Acropolis ishigher than normal. A correction is a necessary, if

arbitrary, measure. Because the attributions are notas dramatically concentrated as at the Sanctuaryof Nymphe and because the Acropolis is a muchlarger and more complex site, only two-thirds ofthe attributions from the Acropolis have been dis-counted for painters active before 480 B.C.E. Thismeasure brings the maximum number of Acropolisattributions belonging to a single painter, theEuergides Painter, down from 43 to 15, which isstill high but is more consistent with the quantitiesobserved after the Persian sack. The attributionsfor painters who began working after 480 B.C.E.have not been adjusted.

Athens, AgoraAnother site of potential preservation bias is

the Athenian Agora, where pottery productioncontinued through the Classical period. However,as revealed in figure 1, the material is relatively

evenly distributed among all the painters in thisstudy, and few have more than seven secure at-tributions. Only the Polos Painter, Lydos, the GelaPainter, and the Theseus Painter have more than 10secure attributions from the Agora. Because mostpainters have only a few attributions, a general

adjustment is not warranted. However, two Agoracontexts, both rich in debris associated with pot-tery production, are potentially overrepresented.20

The first, the Rectangular Rock-Cut Shaft, wasa 20 m deep stratified deposit whose upper 12 maccumulated during the first two decades of thefifth century B.C.E.21The debris included evidenceof pottery production, such as misfired vases andfragments reported to contain pigment. From thecurrent study, only the Gela and Theseus Paintershad a significant number of sherds attributed fromthe context.22 The second problematic context isthe Stoa Gutter Well, the richest ceramic depositin the Agora. Packed with sherds primarily dated

to ca. 520480 B.C.E., a portion of the debris origi-nated from pottery workshops.23 Epiktetos, theEdinburgh Painter, and the Gela Painter are theonly artisans in this study who are representedin the well. As with the archaic Acropolis attribu-tions, only one-third of the sherds from these twounusually rich Agora deposits have been countedin the figures in this study.

Thasos, AgoraOne context outside Athens has been singled

out for preservation bias, the Artemision near theAgora of Thasos.24Excavations since 1958 at the siterecovered tens of thousands of sherds dominated

by Attic black-figure imports. The sanctuary ac-counts for more than half of the attributions fromThasos to painters in this study. Accordingly, onlyone-third of these attributions are counted for theC, Taras, Heidelberg, Griffin-Bird, Theseus, and

18Graef and Langlotz 1925, 1933; Wagner 2003, 53;Stewart 2008a. On this phenomenon for the Panathe-naic amphoras attributed to the Eucharides Painter,see Langridge 1992; 1993, 1416.

19 If the unusually high numbers of attributionsfrom the Athenian Acropolis for archaic painters areconnected to the Persian sack, the Pan Painters 15

works might fit the pattern. Although scholars re-cently have placed the beginning of the Pan Painterscareer at ca. 480 B.C.E., some early works were oncedated to ca. 490 (e.g., CVA Oxford, Ashmolean Mu-seum 1 [Great Britain 3], 26, 44). Because the CalliopePainter also has as many fragments from the Acropo-lis, dating the Pan Painters career to well before 480seems unnecessary, and the lower dating system has

been retained in this study. Eliminating 10 of the PanPainters 15 Acropolis attributions would lower hisproduction rate to well below normal (see appx. 2).

20Monaco 2000, 3454, 18586, 242. A third depos-it, the rich debris from a public dining area (Pit H 4:5),has not been adjusted in this study. A small pit con-

tained material from 475 to 425 B.C.E., which was inlarge part broken and discarded ca. 425 (Rotroff andOakley 1992, 210). Although the context includedsherds attributed to several painters in the study,the best represented, Hermonax and the Villa GiuliaPainter, have only four each. For this reason and be-cause of its wide chronological range, the deposit has

not been adjusted, despite the modest potential foroverrepresentation. See also the commentary on My-son in appx. 2.

21Vanderpool 1946; Moore and Philippides 1986,33132.

22Vanderpool 1946, 266, 269. See also the commen-tary on these painters in appx. 2.

23Thompson 1955, 626; Moore and Philippides1986, 335; Roberts and Glock 1986, esp. 4. For thepainters represented in the deposit, see the respectivecommentaries in appx. 2.

24Daux 1958, 80813; Maffre and Salviat 1976, 774,781; Maffre 1979, 1112.

-

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

6/47

6

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

P.Sapirstein,Methodology,B

ibliography,andCommentaryforthePaintersintheStudy

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

Centaur Painters. Attributions from elsewherein Thasos, which was a major importer of Atticvases in the sixth century B.C.E., have been talliednormally.25

CHRONOLOGY

Establishing a consistent approach to chronolo-gy has been a challenging part of this project. Mostof the best-known painters have published careerranges, but scholars often disagree substantiallyover start and end dates. To resolve discrepanciesin published career lengths, monographs and othercomprehensive studies of individual painters have

been favored. Ideally, an author of a monograph

or dissertation has examined the entire oeuvreof a painter and built a chronology from contextevidence, comparisons to the monumental arts,datable stylistic features, and vase shapes. Indi-vidually dated works then form the framework forestablishing a painters period of activity.

However, there is probably a delay betweenwhen an artisan first began painting and whenhe reached the full rate of production. The datesfavored here represent the beginning and endof major activity for the painter, not the widestrange of dates possible. For example, Oakleyhas identified the decade of 470460 B.C.E. asthe beginning for the Achilles Painter.26There is

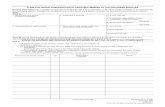

Fig. 1. Attributions from contexts with potential preservation bias. Black-figure specialists are in bold; red-figure specialistsare in italics; (

-

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

7/47

7

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

P.Sapirstein,Methodology,B

ibliography,andCommentaryforthePaintersintheStudy

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

substantial evidence that the Achilles Painter wasin full production by ca. 460 B.C.E., whereas onlya few works could be as early as 470. Because veryfew of his works are dated in the 460s, the date 465B.C.E. has been selected as the beginning of his fullproduction, despite the possibility that the Achilles

Painter decorated some vases in the years before.Some painters in this study lack any published

career range. In these cases, individually datedworks, in particular those published in recenteditions of the CVA, are the basis for assembling aprovisional chronology. Of the painters not studiedin an individual monograph or its equivalent, onlythose for which there are at least 20 dated workshave been included in the figures in this study.

While the chronological resolution for individ-ual vases is not higher than 10- or 5-year intervals,it is possible to achieve a somewhat finer resolutionwhen viewing the whole career of a prolific painter.Scholars often describe an artisan as active a few

years or some time before or after a calendardate rounded to 5 years. Evidence for activity

before or after a 5-year calendar date has beensymbolized with a greater-than or less-than signin print figures 1, 2, and 4. In the calculations, thisis interpreted as 2.5 years. For example, a painterwith nine works dated to ca. 470 B.C.E., 10 to470460, 12 to 460450, and two at midcenturywas probably active at least 20 years (470450),

but the nine early pieces suggest he may havebegun painting regularly as early as ca. 475 B.C.E.The resulting career spans 25 years. If the samepainter had only three to five works dated to ca.470 B.C.E., then he is assumed to have worked for

only the final years of the 470s, for a total career of22.5 years in the calculation of the attribution rate.Print figure 7 presents a more nuanced picture ofthe chronology by plotting the range of possible

beginning and end dates with dashed lines.This approach is effective for painters with

relatively long careers, but it tends to exaggeratethe career lengths of painters active for fewer thantwo decades. For example, a painter with only20 attributions, all dated within 450440 B.C.E.,would appear to have worked 10 years for an at-tribution rate of two works per year. However, theimprecision in his chronology makes it impossibleto determine whether the painter had actually beenactive for only three years, which would triple his

attribution rate to give him more than six vases peryear. The imprecision of the chronology obscuresany meaningful assessment of such a paintersproductivity by both blurring his period of activ-ity and depressing his apparent attribution rate.This effect has probably reduced, although more

subtly, the apparent productivity of the moderatelyproductive specialist painters (see print fig. 2) with100150 works, such as the Painter of London D12and the Veii Painter.

STATISTICALRESULTS

The statistical analysis reveals a remarkableregularity in the attribution rate. For the prolifichands presented in print figure 1, the attributionrates across the group are very homogenous. Over-all, the number of years an Attic painter workedhas a strong linear correlation to his number ofattributions. The Pearsons r-coefficient, whichmeasures linear dependence, is a very strong 0.94.

The group has an average attribution rate of 8.2with a standard deviation of about 0.68. The lattermeasurement is close to what should be expectedfrom the uncertainties in the total number of works

by each painter, his actual career length, and therounding to 2.5-year intervals. Simulating theseconditions on a set of randomized paintersproduces a distribution with a standard devia-tion of 0.60.27

The adjustments to counteract preservationbias do not appear to have affected these results.Only two painters have relatively large adjust-ments to counteract preservation bias. Countingall their works from the Sanctuary of Nymphe and

elsewhere would give the Washing and TheseusPainters 14.9 and 12.0 vases per year, respectively.Excluding these two and Makron, whose highannual productivity can be explained by otherfactors, the adjustments for preservation bias haveno significant effect on the results for the remain-ing 33 painters. The groups overall attributionrate and standard deviation rise to 8.77 and 0.70,respectively. The modest increase in the attribu-tion rate should be expected, since more vases are

being counted. That variance in the data is higherwithout the preservation adjustments, whichhave been targeted only at the few contexts thatare likely to have been overrepresented, indicatesthat these corrections are effective.

27The simulation was conducted by the following procedure: a group of simulated painters are assigned ran-dom career lengths between 15 and 45 years (rounded to the nearest integer), and each painter s total number ofworks is determined by multiplying the career length by 8.2 (vases per assigned year of activity). Next, the careerlength is rounded to 2.5 years, and the attribution rate is recalculated from these new career lengths (already rais-ing the standard deviation to 0.23). Next, to simulate uncertainty in the chronology and attributions, a 5randomerror is introduced into the career length; a 15 error is introduced to the total number of vases; and the attributionrates are recalculated. With more than 10 random trials for 50 painters, the standard deviation is ca. 0.60. Although5 years may seem large for career error, in practice the career length blurred by random error seldom differs fromthe original by more than 2.5 years.

-

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

8/47

8

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

P.Sapirstein,Methodology,B

ibliography,andCommentaryforthePaintersintheStudy

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

The 2.5-year resolution for the chronology isalso defensible. If, for the sake of argument, weround the career lengths of the painters in thestudy to 5-year intervals, the distribution of at-tribution rates becomes less regular. The linearcorrelation between years worked and number

of vases drops to 0.888, which is still significant;the average attribution rate rises to 8.54; and thestandard deviation is a much higher 0.995. Theattribution rate increases slightly because mostpainters have their careers lengthened by the 2.5-year resolution in the study.28That the distributionis more regular at the finer chronological resolutionindicates that the 2.5-year interval is a legitimaterefinement, at least for most painters.

The correlation between years worked and totalnumber of attributions is even stronger when weadd the information about a painters mode ofactivity. If we examine only specialist painters,excluding hands with a large number of problem-

atic attributions, there are 38 artisans from printfigures 1 and 2 whose annual production rangesfrom 7.4 to 9.5 vases. The average rate for thesespecialists rises to 8.3 vases per year, a consequenceof filtering out a few underperforming atypicalpainters like Epiktetos. The standard deviationdrops to 0.58, and the linear correlation (r-value)is strengthened to 0.974.29 When focused only onclear specialists, the data match almost exactly thesimulated distribution.30 We may safely concludefrom this analysis that specialist painters workedat consistent rates.

COMMENTARYONTHEINDUSTRY-WIDEANALYSIS

In print table 1, a critical measurement is thenumber of vases attributed for each 25-year period

between 600 and 400 B.C.E. Although Beazley at-tempted to include all Attic vases from the sixththrough fourth centuries B.C.E., the following gen-erations of scholars have significantly expandedhis lists of attributions. Thus, an attribution rate of

8.3 for specialist painters is based on publicationsup to 2011, and so the raw, unadjusted figures fromBeazleys catalogues are inappropriate for com-parison with the industry as a whole. Furthermore,the expansion in the corpus of attributed vasesvaries by period. Since Beazleys time, more vases

have been published from the sixth century B.C.E.than from the Late Archaic and Classical periods.31

Thus, for print table 1, the method for countingthe total attributed Attic vases has been tailoredto match the conditions of the study of individualpainters. For each 25-year period, the initial tally

begins with Beazleys catalogues of vases, regard-less of the type of attribution. To compensate forthe new attributions since Beazleys death, thetallies from each quartile have been adjustedupward. The adjustment has been determined bythe expansion in the corpus of the painters activein each period. That is, the adjustment is based onthe ratio of a painter s final tally in 2011 to his final

tally in Beazleys Paralipomenain 1971. An averageexpansion of 1015% is typical among the fifth-century painters in this study, but it often exceeds50% for those active at the beginning of the sixthcentury. Thus, 50% has been added to the Beazleycounts for the first quarter of the sixth century,stepping down to +25% by the last quarter of thecentury and +12% for all of the fifth century B.C.E.These adjustments, which have been based on thefinal tallies of studied painters, also compensateroughly for preservation bias. In other words, the38,830 vases in print table 1 do not represent atrue count of all Attic pots with figure decoration

but rather are an approximation of the conditions

imposed in this study.A final note on print table 1: the population

of specialist painters has been determined by as-suming that at least half were prolific enough to

be detected in this project. That is, print figure 7would show us about half of the actual special-ist painters active in each period. Assuming an

28Altogether, 22 painters have their career lengthschanged when the lengths are rounded to 5-year in-tervals; of these, 18 are rounded down and only fourare rounded up. The Gela Painter loses five years from

his total career length, and the rest are altered by 2.5years. There is no net change in career length for the 13other painters. There are fewer than 930 total years ofactivity at 2.5-year intervals, compared with 890 whenthe career lengths are rounded to 5-year intervals.

29The adjusted total for the group is 7,672 vasesover 925 years, or 8.29 works per year. The produc-tivity of black-figure and red-figure artists is indis-tinguishable. The 38 painters are as follows: in black-figure, the Antimenes, Athena, Diosphos, Edinburgh,Gela, Haimon, Swing, and Theseus Painters; in red-figure, Hermonax, Oltos, and Onesimos; the Achilles,Aischines, Altamura, Berlin, Bowdoin, Brygos, Carl-sruhe, Eretria, Euaion, Eucharides, Euergides, Len-

ingrad, Pan, Penthesilea, Phiale, Providence, Reed,Sabouroff, Splanchnopt, Triptolemos, Tymbos, VillaGiulia, and Washing Painters; and the Painters of Bo-logna 417, Munich 2335, the Louvre Centauromachy,

and the Paris Gigantomachy.30Supra n. 27. The simulated standard deviation isca. 0.60, and the r-value is 0.982.

31 Beazley appears to have been more thoroughwith red-figure than black-figure vases, and he alsoindividuated more red-figure than black-figure paint-ers compared with the respective numbers of vases.Furthermore, although new attributions up to hisdeath are compiled in the Paralipomena, Beazleyswork on black-figure painters appeared in only one1956 edition (ABV), whereas he issued the significant-ly expanded second edition of his catalogues of red-figure in 1963 (ARV2); see also Hannestad 1991, 211.

-

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

9/47

9

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

P.Sapirstein,Methodology,B

ibliography,andCommentaryforthePaintersintheStudy

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

average attribution rate of 8.3 vases per year forthese specialists, we can estimate the number ofvases they painted for each 25-year interval. Next,the number of potter-painters is calculated fromthe extra vases in each quartile that are beyondthe productive capacity of the estimated cohort

of specialists. While the productivity of a potter-painter is highly variable, an average annual rateof 3.0 for the group is plausible.32 Because the rateof 3.0 is more of an educated guess based on thelimited data considered here, the population ofpotter-painters is more speculative than that ofthe specialist painters.

The Population of Attic Painters and the RecoveryRatio

Starting with Beazleys corpus, Cook proposedtwo methods to determine the ancient populationof Attic painters.33 First, he noted that about 500individual painters had been distinguished from

the fifth century B.C.E. Guessing an average careerof 25 years, he calculated that about 125 painterswere active simultaneously each year.34 Second,Cook estimated that the total number of extantred-figure vessels or sherds was close to 40,000.He argued that, because typically three or foursherds are attributed to painters over each yearof their careers, about 7090 painters must have

been active over the 150 years when the bulk ofred-figure was manufactured.35Cook split the dif-ference of the two estimates and suggested 100 ormore painters were active at once. Granting threeassistants/potters to every painter, he estimated atleast 400 craftsmen were employed during the fifth

century B.C.E. in Athens. The lower numbers ofsherds from the sixth century, however, indicatedto him that no more than 200 craftsmen were ac-tive at once.

The first method assumes an average painterhad a career of 25 years, yet few of the hundreds ofpainters appear to have been active over so long aperiod. As summarized in print figure 6, a medianBeazleyan hand has fewer than 10 attributions. Ifeach of these hands were a real individual, thecareer length implied by the attribution rate estab-lished in the current project is slightly more than

a year for a specialist or less than five years for apotter-painter. Clearly, the 25-year career assumed

by Cook is far too high.The current study has refined Cooks second

method. His initial assumption that typical vasepainters generated three or four sherds per year

was flawed, and at that time he could not haverecognized the critical distinction between potter-painters and specialists. Still, Cooks study wasimpressively close to the mark, and the currentproject would not have been possible without the50 years of research and publication since Cooksarticle appeared in print.

Cooks study also includes an influential meth-od for estimating the recovery ratio of figural Atticpottery.36He used the preservation of Panathenaicprize amphoras as a proxy for Attic vases in gen-eral. It is possible to estimate the total number ofthe amphoras commissioned for the Panathenaicfestivals from epigraphic sources, from which the

recovery ratio can be determined by comparisonwith the number of extant amphoras in moderncollections. Cooks estimate has been revisitedmany times in the literature.37Estimates from 0.2to 10.0% have been proposed, although approxi-mately 1% is the most common. The recent publica-tion of a comprehensive catalogue of Panathenaicamphoras supports a 1% ratio.38 Several factorsmay have slightly inflated the estimate, however,and the ratio may have been as low as 0.5%.39

Appendix 2: Bibliography andCommentary for the

Painters in the StudyThe Attic Vase Inscriptions (AVI) cited below

can be found in the AVI database (http://avi.unibas.ch/home.html). See the section TallyingSystem in appendix 1 for a discussion of Beaz-leys use of the terms near, in the manner of,and the like. The entry for each painter includessources of recent attributions. The numbers inparentheses preceding these sources refer to thenumbers of certain and uncertain attributions,respectively.

32Although the potter-painters in this study havea somewhat higher annual production of four or fivevases, the methods employed here have tended topick out the more productive potter-painters and toexclude the least productive artisans.

33Cook 1959, 11921.34I.e., 500 painters x 25-year career 100 years =

125 painters per year. Cook (1959) made this estimatebefore Beazleys second edition,ARV2, expanded thedesignations to more than 750 painters and groups.

35At three or four sherds per year, the 40,000 sherds

would take ca. 10,00013,000 years for a single paint-er to generate. Because the time span of the produc-tion is ca. 150 years, roughly 7090 painters wouldhave been active simultaneously.

36Cook 1959, 120.37Webster 1972, 46; Boardman 1979a, 34; Scheibler

1983, 9; 1984, 133; Johnston 1987, 12526; Hannestad1988, 223; Oakley 1992, 199200; Turner 2000, 118;Morris 2005, 959.

38Bentz 1998, 1718 n. 62; 2003, 111; Kotsidu 2001.39Stissi 2002, 269; see also supra n. 10.

-

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

10/47

10

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

P.Sapirstein,Methodology,B

ibliography,andCommentaryforthePaintersintheStudy

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

ACHILLESPAINTER

Beazley (ABV, 409; ARV2, 9861004, 1677, 1708;Paralipomena 43839) lists 232 secure and 48 un-certain attributions. Oakley (1997, 11470) cata-logues 307 works by the painter and 23 nearhim (three more attributed either to him or to the

Phiale Painter are counted in this group). Anoth-er 67 vases loosely connected to the AchillesPainter and 36 in his manner are excluded fromthis appendix.

Chronology: Isler-Kernyi 1973, 24; Boardman1989, 61; Oakley 1997, 59; 2004b, 15.

Recent Attributions (17/8): CVABochum, Kunst-sammlungen der Ruhr-Universitt 2 (Germany81), 12; CVA Moscow, Pushkin State Museum 6(Russia 6), 51; Bentz 1998, 151; Oakley 2004a,713; 2005, 285; Panvini and Giudice 2004, 484;Phoenix Ancient Art 2006, 769; Papili 2009, 242,24748 n. 16.

Mode of Activity: Specialist painter (Type 2) whodominated a workshop with perhaps four pottersand appears occasionally to have painted outsidethe workshop (Kurtz 1975, 413; Euwe 1989, 128;Oakley 1990, 4757, 656; 1997, 7398, 10513).

THEAFFECTER

Beazley (ABV, 23848, 690; Paralipomena 11112)lists 119 secure and two uncertain attributions.Mommsen (1975, 6177, 85115) catalogues 123works by the painter and four near him.

Chronology: Boardman 1974, 65; Mommsen 1975,7781.

Recent Attributions (7/0): CVA Bochum, Kunst-sammlungen der Ruhr-Universitt 1 (Germany79), 367; CVAMunich, Antikensammlungen 10(Germany 56), 39; Kreuzer 1998, 93, 12021, 168;Iacobazzi 2004, 1:209.

Mode of Activity: Potter-painter (Type 5) (vonBothmer 1969, 15; 1980, 94, 106; Boardman 1974,65; Mommsen 1975, 6, 545, 82; Shapiro 1989, 35;Fellmann 1990, 168; Tosto 1999, 197). His stiff, an-gular figures and unique iconography find fewparallels among his contemporaries, and he dec-orated unusual vase forms exclusively.

AISCHINESPAINTER

Beazley (ARV2, 70920, 166768, 1706; Paralipo-mena 40910) lists 260 secure attributions andone uncertain attribution, while 39 works in thepainters manner have not been tallied. Two ofthe three loutrophoroi said to be from the Athe-nian Acropolis, but which are actually very like-ly from the Sanctuary of Nymphe, are excludedfrom the tally (ARV2, 717).

Chronology: CVA Amsterdam, Allard PiersonMuseum 4 (Netherlands 10), 24; CVA Munich,Antikensammlungen 15 (Germany 87), 19. Thepainter was active by the mid 470s B.C.E. giventhe at least seven attributions dated to ca. 470 andcontemporary works in two Kerameikos graves

(Knigge 1976, 115, 146; Kunze-Gtte et al. 1999,84). He remained active through the 440s, withat least 10 attributions at midcentury and two in450440 B.C.E. (CVABochum, Kunstsammlungender Ruhr-Universitt 2 [Germany 81], 59; CVALaon, Muse de Laon 1 [France 20], 29). He mayhave worked until somewhat later.

Recent Attributions (29/2): CVA Adria, MuseoCivico 1 (Italy 28), 3.1.38; CVAAthens, Museumof Cycladic Art 1 (Greece 11), 1078; CVA Bo-chum, Kunstsammlungen der Ruhr-Universitt 2(Germany 81), 59; CVA France 36, 44; CVA Mara-thon, Marathon Museum (Greece 7), 634; CVAMoscow, Pushkin State Museum 4 (Russia 4), 35;CVA Palermo, Collezione Mormino 1 (Italy 50),3.1.6; CVA Vibo Valentia, Museo Statale Vito Ca-pialbi (Italy 67), 345, 38; Knigge 1976, 115, 141,146; 2005, 125; Rotroff and Oakley 1992, 889;Pologiorgi 19931994, 26769; Schwarz 1996, 38;Kunze-Gtte et al. 1999, 43, 72, 834, 91, 152; Pan-vini and Giudice 2004, 500; Panvini 2005, 5960.

Mode of Activity: Specialist painter(?) (by attri-bution rate alone).

ALTAMURAPAINTER

Beazley (ARV2, 58997, 1661) lists 91 secure and

16 uncertain attributions. Prange (1989, 127, 15777, 232) catalogues 95 works by the painter and15 in his manner. Because it is not clear which ofthe pieces in his manner are possible works of thepainter, none is counted, but two uncertain at-tributions from Beazley (ARV2, 597, 1661) not in-cluded by Prange are returned to the tally.

Chronology: New Pauly,Antiquity1:543, s.v. Al-tamura Painter; Prange 1989, 115, 12325; Moore1997, 107; Mannack 2001, 113.

Recent Attributions (3/1): CVATbingen, Antiken-sammlung des Archologischen Instituts derUniversitt 4 (Germany 52), 645; J. Paul Getty

Museum 1983, 76; Rotroff and Oakley 1992, 91;Panvini and Giudice 2004, 473.

Mode of Activity: Potter-painter(?) (Type 5?) inprint figure 5. Specialist painter (Type 2/3) inprint figure 7 because of his high attribution rate(Philippaki 1967, 735; Webster 1972, 367; Prange1989, 356, 38; Frank 1990, 197207). Prange (1989)identifies the Altamura Painter as a potter-painterdespite some evidence that he painted for otherpotters. For example, the Altamura and Niobid

-

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

11/47

11

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

P.Sapirstein,Methodology,B

ibliography,andCommentaryforthePaintersintheStudy

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

Painters decorated two bell kraters by the samepotter, and the Altamura Painter decorated neckamphoras and oinochoai by more than one potter.

AMASISPAINTER(AMASISHIMSELF)

Beazley (ABV, 15058, 688, 714; Paralipomena657)lists 116 secure attributions and one uncertain at-tribution. Von Bothmer (1985b, 11, 23639, 243)catalogues several new vases and raises the totalattributions to 132. Only three of his nine attribu-tions from the Athenian Acropolis are included inthe tally.

Chronology: Boardman 1974, 54; von Bothmer1985b, 15, 39, 239; Moore and Philippides 1986,87; Wjcik 1989, 79; Isler 1994, 94107; Heesen2009, 135. Von Bothmers (1985b) 560515 B.C.E.dates for the painter have been challenged, anda slightly shorter career has been adopted herereflecting the Amasis Painters major activity as

a painter.Recent Attributions (13/5): CVA Kiel, Kunst-halle, Antikensammlung 2 (Germany 64), 567;Kreuzer 1992, 567, 678; 1998, 92, 11819, 145,199200; Papadopoulou-Kanellopoulou 1997,12931, 16970, 17374; Kreuzer 1998, 92, 11819, 145, 199200; Kunze-Gtte et al. 1999, 678;Tuna-Nrling 1999, 42; Iacobazzi 2004, 1:5665;Panvini and Giudice 2004, 409. One of the frag-ments from Samos was already counted in vonBothmer (1985b) and has been excluded fromthe final tally. Two near attributions from theSanctuary of Nymphe have also been excluded

(Papadopoulou-Kanellopoulou 1997).Mode of Activity: Potter-painter (Type 5) (Board-man 1958; 1974, 545; 1987, 14449; 2001, 15051; Webster 1972, 911). At least 10 vases by theAmasis Painter name Amasis aspoietes; two oth-ers signed by Amasis have no figurework; tworecently identified pieces probably signed byhim are in red-figure; and one lekythos recentlyacquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum and at-tributed to the Taleides Painter has an Amasissignature that may be a forgery (AVI, nos. 0077,0119a, 2067b, 2703, 2704, 3070, 3619, 4335, 4941,5734, 6090, 6284, 6987, 8079 [the lekythos with adubious signature is AVI, no. 4926]; von Both-

mer 1985b, 345, 229, 239; Immerwahr 1990, 369;Isler 1994, 946; Williams 1995a, 144; Mommsen1997a, 1718).

Boardman has made a strong case that Ama-sis,poietes, threw and painted his own vases, anassertion supported by a correlation between thepainting and the vase shapes. However, manyhave disputed this combination (Frel 1983, 35 n. 5;Mertens 1987, 18081; Hemelrijk 1991, 253; Mom-msen 1997a, 32; Stissi 2002, 11718, 133). Othersare noncommittal (e.g., von Bothmer 1985b, 379;

Beazley 1986, 52; Isler 1994, 109). Some objectorshave argued that thepoieteswas given the nameAmasis at birth and was thus too young to have

been the painter, given that the Egyptian pharaohAmasis did not ascend to the throne until ca. 570B.C.E. (Isler 1994, 106, 109; Mommsen 1997a,

1823; Stissi 2002, 118). However, this argumentis weak, and it is also possible that Amasis wasan adopted trade name (e.g., Boegehold 1983;Immerwahr 1990, 389; Pevnick 2010). The sameobjectors cite another reason for dividing the pot-ter from the painter: the Egyptian, and perhapsIonian, influence is evident in the potters vases,whereas the painting is solidly grounded in theAttic tradition. However, Nikosthenes, widelyregarded as both potter and painter, exhibits thissame combination of foreign shapes with typicalAttic painting (see the entry for Painter N).

A more credible objection to the combinationcomes from the possibility that the Amasis Paint-

er painted for Neandros. Two vases thrown byNeandros are painted in a style close to that of theAmasis Painter but also related to the styles of Ly-dos and the Heidelberg Painter (Blatter 1971 [byLydos?], 1989 [by the Amasis Painter?]; Brijder1991, 41820; Kreuzer 1992, 678 [by the Heidel-

berg Painter]). Heesen (2009, 13036, 283) takesthe argument further by connecting unsigned

band cups attributed to the Amasis Painter to thepotterwork of Neandros. If this association is con-firmed, these vases do not necessarily imply thatthe Amasis Painter roved about various work-shops. These early vases might instead demon-strate an apprenticeship of the young Amasis to

Neandros, before Amasis became a master potterand painter. Later in his career, Amasis did notpaint for other potters, although he seems to haverecruited outsiders to paint in red-figure (Tiverios1976, 56, 61; Boardman 1987, 144; Isler 1994, 967;Mommsen 1997a, 18, 2332).

ANTIMENESPAINTER

Beazley (ABV, 26682, 69192, 715; Paralipomena11924) lists 158 secure and 70 uncertain attribu-tions. Burow (1989, 79105) catalogues 132 works

by the painter and 16 possibly by him, while sev-en in his manner have been excluded. Four works

attributed to the painter by Beazley but not cata-logued by Burow have been added to the finaltally.

Chronology: Boardman 1974, 109; Moore andPhilippides 1986, 90; Burow 1989, 1, 55.

Recent Attributions (12/6): CVA Adria, MuseoArcheologico Nazionale 2 (Italy 65), 17; CVAAmsterdam, Allard Pierson Museum 5 (Nether-lands 11), 31, 334; CVABerlin, Antikenmuseum7 (Germany 61), 268; CVA Erlangen, Antiken-

-

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

12/47

12

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

P.Sapirstein,Methodology,B

ibliography,andCommentaryforthePaintersintheStudy

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

sammlung der Friedrich-Alexander-Universitt2 (Germany 84), 279; CVA Gttingen, Archolo-gisches Institut der Universitt 3 (Germany 83),346; CVATaranto, Museo Nazionale 4 (Italy 70),9; CVA Urbana-Champaign, University of Illinois1 (United States of America 24), 910; Moore and

Philippides 1986, 112; Shapiro et al. 1995, 10810;Pacini 1996, 81104; Schwarz 1996, 19; Bentz 1998,130; Iozzo 2002, 58, 69; Panvini and Giudice 2004,41617; Phoenix Ancient Art 2006, 1215. Thereare 15 attributions in his manner that have beenexcluded.

Mode of Activity: Specialist painter (Type 2) (Bu-row 1989, 209, 525, 76).

ANTIPHONPAINTER

Beazley (ARV2, 33547, 1646, 1701, 1706; Paralipo-mena36263) lists 104 secure attributions and oneuncertain attribution. It is difficult to distinguishthe painting style from imitators and Onesimos,and works in his manner are unusually numer-ous. The list of 126 pieces in his manner contains22 other possible attributions. Only two of his fiveattributions from the Athenian Acropolis are in-cluded in the tally. If half of the works in the man-ner of the Antiphon Painter were counted as hisown, his attribution rate would rise to about 7.5.

Chronology: CVA London, British Museum 9(Great Britain 17), 28; Blatter 1968, 651; Boardman1979b, 135; Williams 1995b, 9; Gntner 1997, 92.

Recent Attributions (0/11): CVALondon, BritishMuseum 9 (Great Britain 17), 29; CVAMalibu, J.

Paul Getty Museum 8 (United States of America33), 323; CVAParis, Muse du Louvre 19 (France28), 18; Blatter 1968, 64041; 1984, 7; Tamassia1974, 150; Williams 1986a; 1988, 676, 678, 683 n.18; 1995b, 9; Cahn 1993, 15. Blatter (1968) rejectednine Beazley attributions, which have been re-served as uncertain attributions.

Mode of Activity: Specialist painter (Type 3?). Avase signed by Euphronios aspoieteswas recentlyattributed to the Antiphon Painter, and severalothers painted by him are associated with Euph-ronios by shape (AVI, nos. 1361, 2344, 2347, 2352,2707, 3368, 5934, 8113; Bloesch 1940, 703; Beazley1944, 356; Williams 1991a, 51).

ATHENAPAINTER

To the 141 secure and two uncertain works listedby Haspels (ABL, 25460), Beazley (ABV, 52233,704; Paralipomena 26163) adds 34 new and 16uncertain attributions, including some reassign-ments from Haspels lists. Two of his four attribu-tions from the Athenian Acropolis are excludedfrom the tally.

Beazley and Haspels entertained the pos-sibility that the Athena Painter, who worked in

black-figure, was also the Bowdoin Painter, a red-figure hand, although the combination wouldresult in an extremely long unified career (ca.500440 B.C.E.) (Kurtz 1975, 16). Besides havingan implausibly long 60-year career, a combinedpainter would have 9.2 attributed vases per year.

Although the overall rate of the 60-year career isnot exceptionally high, the combination resultsin an implausibly high concentration of worksin the 470s B.C.E., when both hands were activesimultaneously.

Chronology:ABL, 163; CVA Palermo, CollezioneMormino 1 (Italy 50), 3.Y.3; Kurtz 1975, 16, 10911; Wjcik 1989, 279; Borgers 2004, 74. The end ofhis career has been moved up slightly here fromca. 470 B.C.E. because he has few attributionsdated in the 470s B.C.E. (CVAPalermo, Collezi-one Mormino 1 [Italy 50], 3.Y.3; Kunze-Gtte etal. 1999, 778).

Recent Attributions (30/3): CVAAmsterdam, Al-lard Pierson Museum 3 (Netherlands 9), 389,413; CVA Great Britain15, 14; CVAHeidelberg,Universitt 4 (Germany 31), 58; CVA Malibu, J.Paul Getty Museum 2 (United States of America25), 1617; CVAPalermo, Collezione Mormino 1(Italy 50), 3.H.15, 3.H.25,3.Y.34; CVA Paris, Mu-se du Louvre 27 (France 41), 824; CVA Urbana-Champaign, University of Illinois 1 (United Statesof America 24), 25; Papadopoulou-Kanellopoulou1972, 276; Moore and Philippides 1986, 199;Giudice et al. 1992, 11718, 120; Kreuzer 1992,115; Steinhart 1993; Shapiro et al. 1995, 12425;DeVries 1997, 449; Gntner 1997, 645; Kunze-

Gtte et al. 1999, 74, 778, 801; Galoin 2001, 82;Iozzo 2002, 102; Padgett 2003, 25458. One of thetwo fragments from the Sanctuary of Nymphe at-tributed by Papadopoulou-Kanellopoulou (1972)is tallied here.

Mode of Activity: Specialist painter(?) (Type 2).The Athena and Bowdoin Painters decoratedsome lekythoi of the same shape, perhaps whileworking for one potter, and both painters deco-rated other classes of lekythoi (Kurtz 1975, 16, 79,84, 10411).

BELDAMPAINTER

To the 77 secure works and one uncertain work ofthe painter listed by Haspels (ABL, 26670), Beaz-ley (ABV, 58687, 709; Paralipomena29394) adds22 new and 12 uncertain attributions.

Chronology: ABL, 18789; CVA Naples, MuseoNazionale 2 (Italy 71), 34; Kurtz 1975, 135, 153;Nakayama 1982, 245; Turner 1996, 12. Thoughit is often said the painter was active only withinthe second quarter of the fifth century B.C.E., 10of his works are dated to ca. 480 B.C.E. (CVAGela,Museo Archeologico Nazionale 3 [Italy 54], 27;CVANaples, Museo Nazionale 5 [Italy 69], 456;

-

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

13/47

13

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

P.Sapirstein,Methodology,B

ibliography,andCommentaryforthePaintersintheStudy

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

Borriello 2003, 34). Thus, the painter may havebegun during the latter part of the 480s. Fourmore pieces dated to the 460s suggest he mayhave worked through the middle of the decade(CVA Prague, Muse National 1 [Czech Repub-lic 2], 78; CVA Zrich, ffentliche Sammlungen 1

[Switzerland 2], 27; Kunze-Gtte et al. 1999, 712).His period of activity is obscured by the manyworkshop pieces produced during the first half ofthe fifth century.

Recent Attributions (16/6): CVAAmsterdam, Al-lard Pierson Museum 3 (Netherlands 9), 60; CVAAthens, Museum of Cycladic Art 1 (Greece 11),53; CVAGela, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 3(Italy 54), 27; CVA Hannover, Kestner-Museum1 (Germany 34), 33; CVALeiden, Rijksmuseumvan Oudheden 2 (Netherlands 4), 66; CVAMainz,Rmisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum 1 (Ger-many 42), 712; CVANaples, Museo Nazionale2 (Italy 71), 34; CVANaples, Museo Nazionale5 (Italy 69), 456; CVAPrague, Muse National1 (Czech Republic 2), 78; CVA Silifke Museum(Turkish Republic 1), 2; CVATurin, Museo di An-tichit 2 (Italy 40), 3.H.9; CVAZrich, ffentlicheSammlungen 1 (Switzerland 2), 27; lo Porto 1998,16; Kunze-Gtte et al. 1999, 712, 130. Recent at-tributions to the painters manner/workshopare very common, possibly lowering his appar-ent output.

Mode of Activity: Potter-painter(?) (Type 5?).Grounded in the tradition of the Edinburgh,Athena, and Theseus Painters, the Beldam Paint-er specialized in the BEL Class, which was prob-

ably the work of one potter (ABL, 17071, 17679,186; Kurtz 1975, 18, 847, 15354). The distinctivechimney lekythos was another specialty of thepainter, but the Emporion and Haimon Paintersalso decorated the type. The Beldam Painter wasat the center of a workshop where numerous un-attributed vases were produced for decades afterthe painter himself ceased any identifiable activ-ity. His mode of activity thus remains obscure.He may have been a potter-painter who eventu-ally turned to throwing vases full-time for later,anonymous painters, but he may also have beena specialist painter within the workshop.

BERLINPAINTER

Beazley (ABV, 4089; ARV2, 196216, 163436,17001; Paralipomena177, 34446, 520) lists 299 se-cure and 31 uncertain attributions. Cardon (1977,6190) catalogues 315 works by the painter and25 more in his manner, of which only three aretallied as possibly from his hand. Only five of his13 attributions from the Athenian Acropolis areincluded in the tally.

Chronology: New Pauly, Antiquity 2:6045, s.v.Berlin Painter; Beazley 1974a, 6; Cardon 1977,68, 15662, 17778; Boardman 1979b, 94; Kurtz1983; Oakley 1997, 97, 112.

Recent Attributions (15/3): CVA Cleveland, Mu-seum of Art 2 (United States of America 35), 334; CVAMalibu, J. Paul Getty Museum 7 (UnitedStates of America 32), 7; CVAWrzburg, Martinvon Wagner Museum 2 (Germany 46), 53; Robert-son 1983, 5566; 1992, 767, 823; Kotansky et al.1985; Giudice et al. 1992, 153; Cahn 1993, 9; Pas-quier 1995; Moore 1997, 31718; Bentz 1998, 145,165; Neils et al. 2001, 199; Panvini and Giudice2004, 46566; Panvini 2005, 40; Hofstetter 2009,6872. Pinneys (1981) argument for combiningattributions of the Carpenter Painter and relatedhands with those of the early Berlin Painter is notgenerally accepted, nor would it significantly ex-pand the painters total number of works (vonBothmer 1986; Robertson 1992, 802).

Mode of Activity: Specialist painter(?) (Type 2)who led the workshop later dominated by theAchilles Painter (Philippaki 1967, 3142, 15051;Webster 1972, 326; Jubier-Galinier 2009, 514;see also the entry for the Achilles Painter). Onthe vase shapes of the Berlin Painter, see Cardon1977, 163, 199200, 218, 224; Pinney 1981.

PAINTEROFBOLOGNA417

Beazley (ARV2, 90718, 1674, 1707; Paralipomena430, 516) lists 226 secure and six uncertain attri-

butions, excluding two others in the painters

manner.Chronology: His career range is approximate. Hiscollaboration with the Splanchnopt Painter andat least three vases dated to ca. 460 B.C.E. sug-gest he was active by the end of the 460s (CVAMoscow, Pushkin State Museum 4 [Russia 4],378; von Bothmer 1981a, 42). At least eight at-tributions dated to ca. 440 or later suggest he mayhave been active through the mid 430s (CVAAm-sterdam, Allard Pierson Museum 1 [Netherlands6], 8995; CVA Harrow School [Great Britain 21],1920; CVAParma, Museo Nazionale di Antichit1 [Italy 45], 3.1.9).

Recent Attributions (15/3): CVA Athens, BenakiMuseum 1 (Greece 9), 557; CVA Leipzig, An-tikenmuseum der Universitt 3 (Germany 80),11113; CVALille 1 (France 40), 128; CVAMainz,Universitt 2 (Germany 63), 658; CVA Mali-

bu, J. Paul Getty Museum 8 (United States ofAmerica 33), 58; CVA Milan, Collezione H.A.2 (Italy 51), 3.1.56; CVAMoscow, Pushkin StateMuseum 4 (Russia 4), 378; CVA Reading, Uni-versity of Reading 1 (Great Britain 12), 41; CVASt.

-

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

14/47

14

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

P.Sapirstein,Methodology,B

ibliography,andCommentaryforthePaintersintheStudy

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum 5 (Russia12), 76; von Bothmer 1981a, 37; DeVries 1997, 450;Wiel-Marin 2005, 395, 451.

Mode of Activity: Specialist painter(?) (Type 3),because of his affiliation with the Penthesileanworkshop (see the entry for the PenthesileaPainter).

BONN-COLMAR PAINTER

Excluded from the main study but discussedin the print article (p. 503). ARV2, 35157, 1647;Paralipomena 36364; Boardman 1979b, 13435;Pinney 1981, 145; Robertson 1992, 10710. Beaz-ley and subsequent scholars recognized the BonnPainter may have been the early phase of theColmar Painter. The addition of the 19 vases at-tributed to the Bonn Painter or near him raisesthe tally for the combined Bonn-Colmar Painterto about 115 works, including recent attributionsand discounting for some uncertainty.Chronology: Before 500 B.C.E. to after 490 B.C.E.(ca. 15 years).

Mode of Activity: Specialist painter (Type 3). LikeOnesimos and the Antiphon Painter, the ColmarPainter decorated vases thrown by Euphronios,which marks him as a specialist. Separately, theBonn and Colmar Painters have only 2.0 and6.3 works per year, respectively. The combinedpainter, however, fits the typical profile of a spe-cialist with 7.7 works per year.

BOWDOINPAINTER

Beazley (ARV2, 67792, 166566, 1706; Paralipom-ena4067, 514) lists 310 secure and 36 uncertainattributions, of which 34 in the painters mannerhave been excluded. Only one of the five loutro-phoroi from the Sanctuary of Nymphe are includ-ed in the tally (ARV2, 689).

Chronology: ARV2, 678; Lasona 1969, 60; Kurtz1975, 16, 10911; Shapiro 1981, 134; TePaske-King19891991, 345; Moore 1997, 111. Although it isgenerally stated that the painter worked well intothe third quarter of the fifth century B.C.E., theend of his career is undocumented. Dated worksrange from ca. 480 to ca. 450 (CVAPalermo, Col-

lezione Mormino 1 [Italy 50], 3.Y.6; CVA Tbin-gen, Antikensammlung des ArchologischenInstituts der Universitt 5 [Germany 54], 823;Shapiro et al. 1995, 16566).

Recent Attributions (29/6): CVAAmsterdam, Al-lard Pierson Museum 4 (Netherlands 10), 1516;CVA Basel, Antikenmuseum und SammlungLudwig 4 (Switzerland 8), 38; CVA Bryn MawrCollege 1 (United States of America 13), 54; CVAKiel, Kunsthalle, Antikensammlung 1 (Germany55), 8890, 96; CVA London, British Museum 10(Great Britain 20), 70; CVA Palermo, Collezione

Mormino 1 (Italy 50), 3.1.34, 3.Y.6; CVA Sarajevo,Muse National (Yugoslavia 4), 42; CVATbingen,Antikensammlung des Archologischen Institutsder Universitt 4 (Germany 52), 22; Schauenburg1974, 149; Hornbostel 1980, 12627; Shapiro 1981,134; TePaske-King 19891991, 30; Giudice et al.

1992, 16164; Rotroff and Oakley 1992, 878; Sha-piro et al. 1995, 16566; Kunze-Gtte et al. 1999,79, 84; Panvini and Giudice 2004, 47475, 499500; Panvini 2005, 445.

Mode of Activity: Specialist painter (Type 2) (seethe entry for the Athena Painter).

BRYGOSPAINTER

Beazley (ARV2, 36885, 38790, 164950, 1701;Paralipomena 36768) lists 243 secure and fourmore possible attributions among the 53 vases inthe painters manner. These have been countedas 238 and 9, respectively, because five fragments

from the Athenian Acropolis may join others inthe list. Only seven of his 21 attributions (five un-certain) from the Athenian Acropolis are includ-ed in the tally.

Chronology: CVA London, British Museum 9(Great Britain 17), 54; Cambitoglou 1968, 14, 367;Boardman 1979b, 135; Turner 1996, 367; Neer2002, 205; Stewart 2008a, 404. Start dates for hiscareer range between 500 and 490 B.C.E. A begin-ning slightly before 495 B.C.E. is preferred here

because of the relatively high number of attri-butions, at least 12, dated between 495 and 490B.C.E. Similarly, several works are dated to ca.

470, suggesting the painter worked into the early460s B.C.E.

Recent Attributions (28/6): CVA Bochum, Kunst-sammlungen der Ruhr-Universitt 2 (Germany81), 57; CVA Cleveland, Museum of Art 2 (UnitedStates of America 35), 402; CVAMalibu, J. PaulGetty Museum 8 (United States of America 33),368; CVA St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Mu-seum 5 (Russia 12), 41; CVA Wrzburg, Mar-tin von Wagner Museum 2 (Germany 46), 523;Maffre 1982, 20812; 1984, 11516; 2001, 13438;True 1983, 7383; Giudice et al. 1992, 15455;Cahn 1993, 13; Gntner 1997, 12628; Panviniand Giudice 2004, 467; Wiel-Marin 2005, 38081,

445; Phoenix Ancient Art 2006, 503; Heissmeyer2008, 25.

Mode of Activity: Specialist painter(?) (Type 3).For works assigned to Brygos, poietes, by signa-tures or shape analysis, see AVI, nos. 1331, 3553,4473, 6490, 7018, 8111; Bloesch 1940, 815, 12829.Given his high attribution rate, the painter is un-likely to have been thepoietesBrygos but rather afaithful collaborator (Cambitoglou 1968, 7; Web-ster 1972, 13 n. 4, 33; Wegner 1973, 5, 89, 61; Im-merwahr 1990, 889; Robertson 1992, 93; Turner1996, 367; Vollkommer 2001, 125).

-

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

15/47

15

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

P.Sapirstein,Methodology,B

ibliography,andCommentaryforthePaintersintheStudy

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

CPAINTER(CHEIRON?)

Beazley (ABV, 5161, 681; Paralipomena236) lists162 secure and 21 uncertain attributions. Brijder(1983, 13941, 23646; 1991, 47879, 48586; 2000,71719; 2005, 246) catalogues 153 works by him(two in his manner are excluded here) and reas-

signs many works from Beazleys lists to a newhand, the Taras Painter. Although eight of theworks attributed to the C Painter come from theAthenian Agora, the only two with documentedcontexts do not represent a significant preserva-tion bias. Brijder lists 51 pieces from Thasos; ofthese, the 20 from the Artemision are tallied asseven.

Chronology: CVASt. Petersburg, State HermitageMuseum 8 (Russia 15), 1516; CVASt. Petersburg,State Hermitage Museum 10 (Russia 18), 1213;Boardman 1974, 313; Brijder 1983, 24; 1991, 10912; 1996, 37; 2005, 246.

Recent Attributions (6/2): Papadopoulou-Kanel-lopoulou 1997, 112; Iacobazzi 2004, 1:33. The sin-gle attribution from the Sanctuary of Nymphe istallied normally.

Mode of Activity: Potter-painter (Type 5) (Brijder1983, 23, 11014; 2005, 246). The correlation of thepotting and painting is exclusiveno other handsare associated with the potting style (ABV, 59;Brijder 1983, 237; 2005, 255; Immerwahr 1990, 22;Hemelrijk 1991, 253). The C Painter may have beennamed Cheiron, judging from an epoieseninscrip-tion on a Siana cup in the manner of the C Painterfrom the Athenian Acropolis (AVI, no. 1101).

CALLIOPEPAINTER

Beazley (ARV2, 125963, 1688, 1707; Paralipomena471) lists 95 secure and two uncertain attributions.Lezzi-Hafter (1988, 4854, 31157) catalogues 105works by the Calliope Painter and two possibly

by him. There is no adjustment for the 14 Athe-nian Acropolis fragments.

Chronology: Lezzi-Hafter 1988, 4857. The paint-ers major activity was 440420 B.C.E., althoughtwo cups might be slightly earlier (Lezzi-Hafter1988, 50, 311).

Recent Attributions (0/1): One fragment from the

Athenian Agora is possibly by the painter (Moore1997, 328).

Mode of Activity: Specialist painter (Type 2). Al-though he appears to have worked for differentpotters, the Calliope Painter remained within theworkshop of the Eretria Painter (Hoffmann 1962,2930, 47; Lezzi-Hafter 1988, 4857).

CARLSRUHEPAINTER

Beazley (ARV2, 73039; Paralipomena 412, 515)lists 171 secure and three uncertain attributions.

Chronology: CVA Amsterdam, Allard PiersonMuseum 4 (Netherlands 10), 24. The career rangein print figure 1 is approximate but reflects that apreponderance of his works are dated to 460450B.C.E. Two isolated works have been dated to ca.470 and 440 B.C.E., respectively, in early publica-

tions (CVAFogg Museum and Gallatin Collections[United States of America 8], 34; CVAKarlsruhe,Badisches Landesmuseum 1 [Germany 7], 31).

Recent Attributions (12/3): CVAAthens, Museumof Cycladic Art 1 (Greece 11), 10910; CVA Karls-ruhe, Badisches Landesmuseum 3 (Germany 60),813; CVA Moscow, Pushkin State Museum 4(Russia 4), 35, 60; CVASt. Petersburg, State Her-mitage Museum 5 (Russia 12), 7981; CVATaran-to, Museo Nazionale 4 (Italy 70), 18; CVA ViboValentia, Museo Statale Vito Capialbi (Italy 67),356; Rotroff and Oakley 1992, 88; Cahn 1993, 21;Pologiorgi 19931994, 26971; Kunze-Gtte et al.1999, 14, 150; Connor and Jackson 2000, 138.

Mode of Activity: Specialist painter (Type 2)(ABL, 180; Hoffmann 1962, 1925, 47; Webster1972, 36; Kurtz 1975, 1920, 84, 86, 104, 11112).

CENTAURPAINTER(ERGOTELES?)

Beazley (ABV, 18990, 689; Paralipomena 789)lists 28 secure and four uncertain attributions.Heesen (2009, 21112, 31124, 331) greatly ex-pands the corpus with 163 works by the painter,while 12 more in his manner have been excluded.One attribution from the Athenian Acropolis hasnot been adjusted. Only two of the four attribu-

tions from the Artemision at Thasos are tallied.Chronology: Heesen 2009, 250.

Recent Attributions: No new attributions sinceHeesen (2009) have been included.

Mode of Activity: Potter-painter (Type 5) (Heesen2009, 21114; 227; 232; 302, cat. no. 390 [a pos-sible collaboration of Tleson and the CentaurPainter]). Although the Centaur Painters workis unsigned, it is closely related to that of Tleson,as if he worked in Tlesons studio. Heesen (2009)suggests the Centaur Painter may have been Er-goteles, who is known from apoietes inscriptionas a son of Nearchos and thus a brother of Tleson.

CODRUSPAINTER

Beazley (ARV2, 126873, 75, 1689; Paralipomena472) lists 51 secure and 14 uncertain attributions.Avramidou (2005, 15, 19, 21, 27187; 2011, 256,8796) catalogues 78 works by the painter in her2005 dissertation but has reduced the total to 65secure and 12 possible attributions in her subse-quent monograph.

Chronology: New Pauly,Antiquity3:504, s.v. Co-drus Painter; Isler-Kernyi 1973, 30; Turner 1996,

-

8/12/2019 1174 Sapirstein Suppl

16/47

16

AmericanJournalofArchaeologyOctober2013(117.4

)

P.Sapirstein,Methodology,B

ibliography,andCommentaryforthePaintersintheStudy

Copyright2013bytheArchaeologicalInstituteofAmerica

512; Avramidou 2005, 15, 19, 21, 251; 2011, 56,235, 7281.

Recent Attributions: No new attributions sinceAvramidou (2011) have been included.

Mode of Activity: Potter-painter(?) (Type 5) (New

Pauly, Antiquity 3:504, s.v. Codrus Painter;Lezzi-Hafter 1988, 73, 8697; Avramidou 2011,22). The profiles of the Type B kylikes by the Co-drus Painter are distinct from related cups paint-ed by the Eretria Painter and his associates.

DIOSPHOSPAINTER