08 JGVR Ayta Legend Paper

-

Upload

patricia-moran -

Category

Documents

-

view

229 -

download

2

description

Transcript of 08 JGVR Ayta Legend Paper

-

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attachedcopy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial researchand education use, including for instruction at the authors institution

and sharing with colleagues.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling orlicensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party

websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of thearticle (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website orinstitutional repository. Authors requiring further informationregarding Elseviers archiving and manuscript policies are

encouraged to visit:

http://www.elsevier.com/copyright

-

Author's personal copy

A prehistoric lahar-dammed lake and eruption of Mount Pinatubo described in aPhilippine aborigine legend

Kelvin S. Rodolfo a,b,, Jesse V. Umbal a,1

a Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago, 845 W. Taylor St., Chicago Il 60607 USAb National Institute of Geological Sciences, University of the PhilippinesDiliman, Quezon City, Philippines

A B S T R A C TA R T I C L E I N F O

Article history:Accepted 24 January 2008Available online 27 May 2008

Keywords:aboriginal volcano legendAytacaldera-forming eruptionlahar-dammed lakePinatubo volcano

The prehistoric eruptions of Mount Pinatubo have followed a cycle: centuries of repose terminated by acaldera-forming eruption with large pyroclastic ows; a post-eruption aftermath of rain-triggered lahars insurrounding drainages and dome-building that lls the caldera; and then another long quiescent period.During and after the eruptions lahars descending along volcano channels may block tributaries fromwatersheds beyond Pinatubo, generating natural lakes. Since the 1991 eruption, the Mapanuepe River valleyin the southwestern sector of the volcano has been the site of a large lahar-dammed lake. Geologic evidenceindicates that similar lakes have occupied this site at least twice before. An Ayta legend collected decadesbefore Mount Pinatubo was recognized as a volcano describes what is probably the younger of these lakes,and the caldera-forming eruption that destroyed it.

2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

MountPinatubovolcanoandMountsNatib andMariveles to the southbelong to a chain of stratovolcanoes along western Luzon Island in thePhilippines, resulting from eastward subduction of South China Basinlithosphere along the Manila Trench (Fig. 1). Isolated areas in centralLuzon are inhabited by Aytadark-skinned, curly-haired aborigines ofshort stature also called Ita, Agta, and, most commonly Aeta. At Pinatubo,these people prefer to be called Ayta, as the word sounds and as itwould be correctly spelled in Pilipino. The etymology of Pinatubo ispertinent to this report; -tubo is the root in both the Pilipino (Tagalog) andAyta languages that pertains to anything concerned with growth. Here,the prex pina- creates made to grow. Pinatubo may as easily meanallowed to grow, in the same sense that not felling or pruning a treeallows it to grow. Volcanologists speculate that the namemay imply thatAytaswitnessed the post-eruption growth of a newpeak (Rodolfo,1995).Interestingly, the Ayta commonly refer to themselves as the katutubo.Shimizu (1992, p. 7) translated the term tomean theones fromthe land,but it transliterates to those who grew (or sprouted) with.

Pinatubo's cataclysmic 1991 eruption, and what is known of itsgeologic history, are described in encyclopedic detail in the 1 126-pagecompendium Fire and Mud (Newhall and Punongbayan, 1996). Beforethe 1991 eruption the Pinatubo peak was the highest point in the

Zambales Range. Standing 1745 m above sea level, it served as thebenchmark for the point where Pampanga, Zambales and Tarlacprovinces meet. Pinatubo was recognized as a volcano by only a fewgeologists before 1991, being nestled inconspicuously in surroundingophiolitic mountains that stood only 200 m or so lower. Localinhabitants had little experience or folk memory of an eruption beyondthe Ayta legend discussed in this report, due to its centuries of repose.

During the paroxysmal eruption of 15 June 1991, the volcanocollapsed to form a roughly circular, 2.5 kmwide caldera with its oorat an altitude of 820 m (Fig. 2). Pinatubo's new highest point on thesoutheastern jagged caldera rim stands only 1485 m above the sea,260 m lower than the old peak.

The eruption left more than 5 km3 of pumiceous debris on thevolcano anks. During the ensuing 5 years, torrential monsoonal rainsenhanced by typhoons mobilized great volumes of the debris intodestructive lahars that owed down all major drainages of the volcano,damaging or obliterating many villages and towns (Bautista, 1996;Spence et al., 1996). Economic losses from the eruption and its laharicaftermath are estimated at a billion US dollars (Mercado et al., 1996).Aytas were the worst affected among as many as two million peoplearound the volcano. The frequency and sizes of lahars have greatlydiminished, but voluminous lahar deposits along the volcano front maystill be remobilized by exceptional future storms (Umbal, 1997).

During and after the eruption, lahars descending along volcanodrainages dammed the conuences of tributary streams that drainareas outside the Pinatubowatershed, impounding ponds and lakes ofvariable permanence. When the impounded water overtopped thedebris dams, the released oods would generate lake-breakout

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 176 (2008) 432437

Corresponding author. E8022 BakkomRd, ViroquaWI 54665, USA. Tel.: +1608 6376159.E-mail address: [email protected] (K.S. Rodolfo).

1 Present address: Avocet Bolaang Mongondow, Jl.Kolonel Sugiono No. 24, Kotaban-gon, Kecamatan Kotamobagu, Sulawesi Utara, Indonesia.

0377-0273/$ see front matter 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2008.01.030

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research

j ourna l homepage: www.e lsev ie r.com/ locate / jvo lgeores

-

Author's personal copy

lahars, including extremely devastating events in 1991,1992, and 1994(Newhall et al., 1996). Unlike rain-triggered lahars, those generated bylake breakouts were difcult to predict, happened after typhoonswhen people had dropped their guard, and often occurred at night,thus were especially dangerous. Mapanuepe Lake in the southwesternsector of the volcano (Fig. 3; Umbal, 1994; Umbal and Rodolfo, 1996) isthe only such lahar-dammed lake large enough to survive until thiswriting.

Pinatubo eruptivity, its timing and associated events are poorlyunderstood, and clues regarding them are urgently needed. Toward thatend, folklore has been scrutinized by Gaillard et al. (2006a,b). Closerexamination of a legend transcribed in 1915 (Rodriguez, 1918), the focus

of this report, provides clear evidence that a lahar-dammed lake wasformed during the penultimate prehistoric eruption and survived until itwas destroyedby the last eruption before the1991 event. To examine thelegendproperly requires familiaritywithPinatubo's eruptive chronology,and with two of its geomorphic features: an ancient caldera and, in thesouthwestern sector of the volcano, Mapanuepe Lake and its ancestors.

2. Eruption chronology of Mount Pinatubo

Newhall et al. (1996) have cited evidence that Pinatubo's pasteruptions have followed a cycle of centuries of repose terminated by apowerful eruption with a caldera collapse, large pyroclastic ows andlahars, followed by an aftermath period of post-eruption lahars.Finally, a period of dome-building associated with eruptions ofuncertain intensity and duration lls the caldera before the volcanoenters another long quiescent period.

Fig. 1. Locations of the Philippines and Mount Pinatubo (shaded gray).

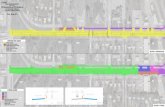

Fig. 2. The new Pinatubo caldera, and arcuate scarps A, B and C interpreted as remnantsof the Tayawan Caldera. Modied from Lagmay et al., 2007.

Fig. 3. Mapanuepe Lake in relation to the new caldera. Base: composite of Landsatphotographs 116_050_2611_2001 and 117_049_01_2001.

433K.S. Rodolfo, J.V. Umbal / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 176 (2008) 432437

-

Author's personal copy

Most of the data onwhich thismodel of cyclic eruption is basedweregathered shortly after precursory seismic activity began at Pinatubo on15 March 1991 and the rst small explosions occurred north of thesummit on 2 April (Wolfe and Hoblitt, 1996). To develop a hazard map,geologists of the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismologyimmediately began a heroic attempt to study the style andmagnitude ofpast eruptions. Theywere joined in late April by geologists of the UnitedStates Geological Survey. Given the short time before the eruption, aremarkable amount of evidence was gathered, but the data werenecessarily incomplete. Thus, drawing on radiocarbon dates of 51samples, Newhall et al. (1996) hypothesized that the modern series ofsix prehistoric eruptions began around 35 ka BP, and that eruptionsmaybe getting weaker over time after successively shorter periods of repose(Fig. 4). These authors acknowledged, however, that those trendsmaybeartifacts of the erosion or burial of older deposits. Dates for the earliestthree eruptions are each based on only one or two samples, and a gap inthe coverage was recently demonstrated by a single sample from anancient caldera-lake deposit with an uncalibrated C14 age of 14,70040yBP (Lagmayet al., 2004; Rodolfo, 2005; Lagmayet al., 2007;Gaillardet al., 2006b). The last two of the prehistoric eruptions, the Maraunotand Buag episodes that respectively occurred ca. 3.93.3 and 0.80.5 kaBP are of immediate interest here.

2.1. The prehistoric Tayawan Caldera

While Pinatubo was still regarded as extinct, Deln and his co-workers (1984, 1996) conducted the rst systematic studies of itsgeology to assess its geothermal resources. They mapped three arcuatescarps, labeledA, B andC in Fig. 2. Newhall et al. (1996) interpreted thosefeatures as remnants of an old, 3.54.5 km collapse depression, whichthey named the Tayawan Caldera and interpreted as having beenproduced by the earliest, and presumably strongest episode, the Inararoepisode ca. 35 ka BP (Fig. 4). A problem is posed by the date of 14,70040 y BP recently obtained from lacustrine deposits nowwidely exposedin the walls of the new caldera. Those sediments may have beendeposited in yet another caldera, formed after the Inararo eruption.Either that event was a previously unrecognized eruption, or ithappened late during the Sacobia eruptive period, which would havehad to last more than 2000 years longer than indicated in Fig. 4.Alternatively, if those sediments really were deposited in the TayawanCaldera, it is much younger than previously thought.

2.2. Mapanuepe Lake and its prehistoric predecessors

Before the 1991 eruption, the Mapanuepe River drained 88 km2 ofmountainous watershed south of Mount Pinatubo. It joined theMarella River descending the southwest Pinatubo ank, to form theSanto Tomas River, which follows the northern margin of its broad,235-km2 alluvial plain en route to the South China Sea. During the1991 eruption, large lahars descending along the Marella River

blocked the Mapanuepe River, transforming it into the lake thatnow bears the same name (Fig. 3). The evolution of Mapanuepe Lakewas observed and documented from its inception (Umbal, 1994;Umbal and Rodolfo,1996). At its maximum extent the lake had an areaof 6.7 km2 and a volume of about 7.5107 m3.

Sedimentary ll (Fig. 5) and geomorphology (Fig. 6) indicate thatsimilar lahar-dammed lakes occupied the site during at least twoprevious eruptions. Several terraces rim theMapanuepe catchment areaand the adjacent valley of the Santo Tomas River. One terrace, 15 mhigher than the pre-eruption oor of the Santo Tomas River at Sitio(hamlet) Dalanaoan is composed of pyroclastic-ow deposits overlainby lahar deposits that yielded charcoal samples dated at 299070 and293080 14C years, which place them in theMaraunot eruptive episodeof Newhall et al. (1996). Similar, undated pyroclastic-owdeposits occurat a site near the now-buried Sitio Aglao. There, another terrace 5 mlower than the Dalanaoan section was composed of old lahar depositscontainingyoungercharcoal, about7606014C years old, correspondingto the earlier part of the Buag episode.

3. Anthropological evidence

3.1. The Aytas

When the Spaniards conquered the Pampanga region north ofManila Bay and southeast of Mount Pinatubo in 1571, Austronesian-speaking, Muslim, Kapampangan agriculturists were already well-established there, but apparently had no tradition of a large eruption.Had the last one occurred 500 y BP, a few witnesses would still havebeen alive. This suggests that the main Buag eruption occurred earlierrather than later (Gaillard et al., 2006b), or that the later phases of itsactivity occurred away from the southern and eastern sectors.

At the time of the 1991 eruption, as many as 10,000 Aytas inhabitedPinatubo and its mountainous environs (Seitz, 2004). These aboriginessubsist by hunting, shing, gathering and swidden farming (Shimizu,1989).

The 16th century Spanish conquistadores collectively referred to theAytas and similar Philippine tribes as Negritosowing to their dark skin,curly hair, and short stature. Modern scholars include as Negritos notonly the twelve ethnically related mountain tribes isolated onmountainousareasof fourPhilippine islands, but theAndaman islandersin the eastern Bay of Bengal and tribes inwesternMalaysia and Thailandaswell. In the early 20th century the Negritoswere commonly assumedto be related to the pygmies of Africa (Waterman,1924). In the Forewordtohis 1963book, however, Garvan,whoclaimed tobe probably theonlyanthropologist who knows both the Asiatic Negritos and the AfricanPygmies by personal experience, said, Their comparison showed thatthey formby nomeans a racial or cultural unit.Omoto (1981) arrived atthe same conclusion from genetic information from blood analyses. TheNegritos are now generally regarded as the only survivors of aboriginal,pre-mongoloid Asians (Headland and Reid, 1989).

Fig. 4. Chronologies of Pinatubo eruptions (from Newhall et al., 1996; the new date from Lagmay et al., 2004, 2007; Rodolfo, 2005),the hypothesized arrival in the Philippines of theAytas and their presence at Pinatubo indicated by the legend.

434 K.S. Rodolfo, J.V. Umbal / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 176 (2008) 432437

-

Author's personal copy

The Aytas and other Philippine Negritos do not build boats (Kreiger,1942), and it is generally believed that they are descendants of peoplewho crossed land bridges from the southeast Asian mainland to thePhilippines during the last Pleistocene drop in sea level, which attainedits nadir of about 130mbelowpresent sea level some18 kaBP (Pirazzoli,1998). The scientic consensus is that the inux of Austronesian-speaking people from mainland Southeast Asia occurred about vemillennia ago, which would have been sometime between Pinatubo'sCrow Valley and Maraunot eruptive episodes (Fig. 4). It has long beenclaimed that the technologically more advanced newcomers killed theNegritos or drove them into the hills (Brinton, 1898). That, however, iscontradicted by the fact that the Aytas of western Pinatubo have losttheir original language and adopted that of the lowland Zambalnewcomers (Peralta, 1990), from whom they also borrowed manyother cultural traits (Headland and Reid, 1989). If the Aytas wereeventually forced to retreat to Pinatubo, it would have been at someconsiderable timeafter the Zambal arrival. TheAyta legend suggests thatthey were already at Pinatubo no later than during the repose periodbetween the Maraunot and Buag eruptions.

3.2. The legend

Gaillard et al. (2006a,b) discussed several legends of the lowlandKapampangan people that may suggest knowledge of Pinatubovolcanism, but these are very equivocal. Hardly less vague is theAyta tradition, before the 1991 eruption, of warning their children thatApo Pinatubo Namalyari [the god of the mountain they worship] willwake up and start throwing stones if you don't behave (Rodolfo, 1995p. 88). But an Ayta legend contains much detail that strongly indicatesfolk memory of an eruption. Collected in 1915 (Rodriguez, 1918), thelegend survives only as a somewhat garbled typewritten transcriptionon microlm in the Filipiniana collection of the main library of theUniversity of the Philippines in Diliman, Quezon City. It carries specialweight because it was collected long before geologists recognized thatPinatubo was a volcano.

Like most legends, it has several confusing elements. Its two principalprotagonists are a mighty, supernatural hero named Aglao, king of theSpirit Hunters, and a powerful, villainous spirit named Bacobaco. Thename Aglao is signicant only because it was the name of a hamlet near

Fig. 5. Stratigraphic sections near the Mapanuepe basin. Modied from Umbal (1994).

435K.S. Rodolfo, J.V. Umbal / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 176 (2008) 432437

-

Author's personal copy

theMarellaMapanuepeconuence thatwasburiedby the lake-damminglahars in 1991 following the paroxysmal eruption (Fig. 3); otherwise, it isthe name of an herb that Aytas use as a medicine for gastrointestinal ills(Fox, 1952). Bacobaco is

the terrible spirit of the sea who makes the storms and thewaves. Bacobaco was also extremely fond of deer's meat andsometimes he would transform himself into an enormous turtle;and suddenly appearing on the shore of the sea, he would sallyforth into the hunting grounds of the Spirit Hunters and gorgehimself with deer Aglao would greatly resent this, but howcould he face Bacobaco who carried his thick shield on his back,and who threw re from his mouth?

However, one day, he consultedWasi, the spirit of thewind. AndWasiwhispered into his ear, Why don't you ask Blit, my brother, to helpyou? He is the only one capable of killing Bacobaco, for if he hits [himwith] the tipofhis tail [?] ora toeof oneofhis feet, itwill kill Bacobaco.

It is unclear who Blit isan earthquake god, perhaps, judging fromhis strengthbut he joins Aglao and the other Spirit hunters, andattacks Bacobacowith arrows. Bacobaco manages to avoid being hit,but ees towardthe lake at the foot of Mount Pinatubu [sic].

Again, Bacobaco escaped injury byhiding himself under his shield. Heimmediately jumped into the lake but the water was so clear, that Blitcould see him at the bottom. Finding the lake a useless place of refuge,he climbed the Mount Pinatubu in exactly twenty-one tremendousleaps.When he had reached the top, he at once began to dig a big holeinto the mountain. Bit [sic] pieces of rock, mud, dust, and other thingsbegan to fall in the showers around themountain. During all thewhile,he howled and howled so loudly that the earth shook under the foot[sic] of Blit [and] Aglao There that escaped fromhismouth becameso thick and so hot that the pursuing party had to turn away.

For three days the turtle continued to burrow itself, throwing rocks,mud, ashes, and thunderingawayall the time in [a] deafening roar. Atthe end of the three days he stopped, and all was quiet again in themountain. But the lake, with its clear water was now lled withrocks, and mud covered everything. On the summit of the Pinatubuwas the great hole, through which Bacobaco had passed, and from

which smoke could be seen constantly coming out. This showed thatalthough he was already quiet he was still full of anger, since recontinued to come from his mouth

The legend's elements of clear volcanological interest are a pre-eruption lake of clear water at the base of Pinatubo, and a thunderouseruption with ery pyroclastic ows lasting three days that threw outgreat quantities of debris that lled the lake below and left a summitcaldera.

4. Discussion and conclusion

The chronology depicted in Fig. 4 and the salient elements of thelegend suggest that Aytas were already occupying Pinatubo after theMaraunot eruption had formed a proto-Mapanuepe Lake, andwitnessed its destruction by tephra-falls, pyroclastic ows and laharsduring the calderagenic Buag eruption. Pyroclastic ows are alsoindicated by the basal pyroclastic-ow deposits of Maraunot-episodeage at Dalanaoan, which likely correlate with similar basal deposits inthe upper Aglao stratigraphic section (Fig. 5).

Perhaps, as Newhall et al. (1996) have suggested, the Buag eruptionwas not as strong as its predecessor and produced less debris tomobilize into lahars that blocked the drainage of the Mapanuepevalley. The resulting smaller proto-Mapanuepe Lake would have beenlled in more easily and over less time by deposits that weresubsequently eroded, leaving the lower terrace (Fig. 6). Similarly, the1991 eruption and its aftermath lled the Mapanuepe valley even lessthan did the Buag event, lending weight to the conjecture thatPinatubo eruptions have become successively weaker, at least for thelast three events.

Legends commonly distort the time dimension, but a calderacollapse lasting three days equates reasonably well with the 1991counterpart event. The legend tells us nothing about whether theAytas experienced any of the pre-Buag eruptions. If these indeed werelarger than the Buag event, it would not be surprising if no witnessesever returned. Quiescent intervals lasting as long or longer than theone that preceded the 1991 eruption would have diminished thepossibility that folk memories of them would have survived.

No legend relates how dome-building eruptions lled the Buagcaldera and erected the pre-1991 summit peak. This is unfortunate,because large, lahar-generating oods expelled by dome-buildingeruptions under the present caldera lakemay pose Pinatubo's greatestfuture hazard (Lagmay et al., 2007). As described elsewhere (Rodolfo,1995), the Aytas are the most environmentally aware people we haveever had the good fortune to work among and learn from; perhaps

Fig. 6. Cartoon recreating the history of successive lacustrine inllings and incisions of the Mapanuepe area since the Maraunot eruptive episode. Modied from Umbal (1994).

436 K.S. Rodolfo, J.V. Umbal / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 176 (2008) 432437

-

Author's personal copy

loitering around Pinatubo to watch its dome grow would simply havebeen too foolhardy.

The Ayta narrator does, however, conclude the legend by fore-telling the 1991 eruption: But now, you do not see smoke coming outof the Pinatubo mountain and many believe that the terriblemonster is already dead; but I think that he is just resting after hisexertions, and that someday hewill surely come out of his hiding placeagain

References

Bautista, C.B., 1996. The Mount Pinatubo disaster and the people of Central Luzon. In:Newhall, C.G., Punongbayan, R.S. (Eds.), Fire and Mud: Eruptions and Lahars ofMount Pinatubo. University of Washington Press, Seattle, pp. 151164.

Brinton, D.G., 1898. The peoples of the Philippines. American Anthropologist XI (10),293307.

Deln, F., 1984. Geology of the Mt. Pinatubo area. Philippine National Oil CompanyTechnical Report.

Deln, F., Villarosa, H., Laguyan, D., Clemente, V., Candelaria, M., Ruaya, J., 1996.Geothermal exploration of the pre-1991 Mount Pinatubo hydrothermal system. In:Newhall, C.G., Punongbayan, R.S. (Eds.), Fire and Mud: Eruptions and Lahars ofMount Pinatubo. University of Washington Press, Seattle, pp. 197212.

Fox, R.B., 1952. The Pinatubo Negritos: their useful plants and material culture.Philippine Journal of Science 81 (34), 173394.

Gaillard, J.-C., Deln Jr., F.G., Dizon, E.Z., Larkin, J.A., Paz, V.J., Ramos, E.G., Remotigue, C.T.,Rodolfo, K.S., Siringan, F.P., Soria, J.L.A., Umbal, J.V., 2006a. A reconstruction of theca. 800500 BP. Buag eruption of Mt. Pinatubo, Philippines. In: Grattan, J.A.,Torrence, R. (Eds.), Living Under the Shadow: The Archaeological, Cultural andEnvironmental Impact of Volcanic Eruptions. University College London Press,London.

Gaillard, J.-C., Deln Jr., F.G., Dizon, E.Z., Larkin, J.A., Paz, V.J., Ramos, E.G., Remotigue, C.T.,Rodolfo, K.S., Siringan, F.P., Soria, J.L.A., Umbal, J.V., 2006b. The 800500 y BPeruption of Mt. Pinatubo and its aftermath: hypotheses from the archaeological andgeographical records. Fourth International Cities on Volcanoes Conference, Quito,Equador, January 2327.

Garvan, J.M., 1963. The Negrito of the Philippines. In: Hochegger, H. (Ed.), WienerBeitrage zur Kulturgeschichte u. Linguistik, vol. 14. Horn-Wein, Berger.

Headland, T.N., Reid, L.A., 1989. Hunter-gatherers and their neighbors from prehistory tothe present. Current Anthropology 30 (1), 4366.

Kreiger, H.W., 1942. Peoples of the Philippines. The Smithsonian Institution,Washington D.C.

Lagmay, A.M.F., Rodolfo, K.S., Siringan, F.P., Uy, H., Remotigue, C.T., Zamora, P., Lapuz, M.,Rodolfo, R., Ong, J.B., 2007. Geology and hazard implications of the Maraunot Notchin the Pinatubo caldera, Philippines. Bulletin of Volcanology. doi:10.1007/s00445-006-0110-5 13 pp.

Lagmay, A.M.F., Uy, H., Rodolfo, K.S., Siringan, F.P., Remotigue, C.T., Lapuz, M., Rodolfo, E.,Zamora, P., Ong, J., 2004. Geology and structures of the Maraunot caldera notch,Pinatubo, Philippines. General Assembly of the International Association ofVolcanology and Chemistry of the Earth's Interior, Pucon, Chile, 16 November.

Mercado, R.A., Lacsamana, B.T., Pineda, G.L., 1996. Socioeconomic impacts of the MountPinatubo eruption. In: Newhall, C.G., Punongbayan, R.S. (Eds.), Fire and Mud:

Eruptions and Lahars of Mount Pinatubo. University of Washington Press, Seattle,pp. 10631070.

Newhall, C., Daag, A., Deln Jr., F.D., Hoblitt, R., Mc Geehin, J., Pallister, J., Regalado, M.,Rubin, M., Tubianosa Jr., B., R., Umbal, J.V., 1996. Eruptive history of Mount Pinatubo.In: Newhall, C.G., Punongbayan, R.S. (Eds.), Fire and Mud: Eruptions and Lahars ofMount Pinatubo. University of Washington Press, Seattle, pp. 165196.

Newhall, C.G., Punongbayan, R.S. (Eds.), 1996. Fire and Mud: Eruptions and Lahars ofMount Pinatubo. University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Omoto, K., 1981. The genetic origins of the Philippine Negritos. Current Anthropology 22(4), 421422.

Peralta, J.T., 1990. Notes on the Buag Agta of San Marcelino, Zambales. National MuseumPapers 1 (2), 140.

Pirazzoli, P.A., 1998. Sea-level Changes: The last 20,000 years. John Wiley and Sons Ltd.,London. 211 pp.

Rodolfo, K.S., 1995. Pinatubo and the Politics of Lahar. University of the PhilippinesPress, Quezon City, Philippines.

Rodolfo, K.S., 2005. The Maraunot Fault: a major structural control of volcaniclasticsedimentation in the northwestern sector of Pinatubo Volcano. Program, AGUChapman Conference on the Effects of Basement, Structure, and StratigraphicHeritages on Volcano Behaviour, Tagaytay City, Philippines, 1620 November, p. 31.

Rodriguez, J.N., 1918. The origin of Pinatubu volcano (A Negritomyth). In: Beyer, H.O. (Ed.),Philippine folklore, social customs and beliefs (a collection of original sources)Volume XXII: Ethnography of the NegritoAyta peoples. Manila, Philippines.

Seitz, S., 2004. The Aeta at the Mt. Pinatubo, Philippines: A Minority group Coping withDisaster. Translated from the original German by Michael Bletzer. New Day Press,Quezon City, Philippines.

Shimizu, H., 1989. Pinatubo Aytas: Continuity and Change. Ateneo de Manila UniversityPress, Quezon City, Philippines.

Shimizu, H., 1992. Past, present and future of the Pinatubo Aetas. In: Shimizu, H. (Ed.),After the Eruption: Pinatubo Aetas and the Crisis of their Survival. Tokyo,Foundation for Human Rights in Asia, p. 7.

Spence, R.J.S., Pomonis, A., Baxter, P.J., Coburn, A.W., White, M., Dayrir, M., FielsEpidemiology Training Program Team, 1996. Building damage caused by the MountPinatubo eruption of June 15, 1991. In: Newhall, C.G., Punongbayan, R.S. (Eds.), FireandMud: Eruptions and Lahars of Mount Pinatubo. University of Washington Press,Seattle, pp. 10551062.

Umbal, J.V., 1994. Lahar-dammed Mapanuepe Lake: two-year evolution after the 1991eruption of Mount Pinatubo, Philippines. Master's thesis, Department of Earth andEnvironmental Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Umbal, J.V., 1997. Five years of lahars at Pinatubo Volcano: declining but still potentiallylethal hazards. Geological Society of the Philippines Journal 52, 119.

Umbal, J.V., Rodolfo, K.S., 1996. The 1991 lahars of southwestern Mount Pinatubo andevolution of the lahar-dammed Mapanuepe Lake. In: Newhall, C.G., Punongbayan,R.S. (Eds.), Fire and Mud: Eruptions and Lahars of Mount Pinatubo. University ofWashington Press, Seattle, pp. 951970.

Waterman, T.T., 1924. The subdivisions of the human race and their distribution.American Anthropologist 26, 474490.

Wolfe, E.W., Hoblitt, R.P., 1996. Overview of the eruptions. In: Newhall, C.G.,Punongbayan, R.S. (Eds.), Fire and Mud: Eruptions and Lahars of Mount Pinatubo.University of Washington Press, Seattle, pp. 320.

437K.S. Rodolfo, J.V. Umbal / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 176 (2008) 432437