07-044503

-

Upload

amrina-rosyada -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of 07-044503

-

7/28/2019 07-044503

1/8

365Bulletin o the World Health Organization | May 2008, 86 (5)

Vaccines to prevent pneumonia and improve child survivalShabir A Madhi,a Orin S Levine,b Rana Hajjeh,b Osman D Mansoor c & Thomas Cherian d

Abstract For more than 30 years, vaccines have played an important part in pneumonia prevention. Recent advances have createdopportunities or urther improving child survival through prevention o childhood pneumonia by vaccination. Maximizing routineimmunization with pertussis and measles vaccines, coupled with provision o a second opportunity or measles immunization, hasrapidly reduced childhood deaths in low-income countries especially in sub-Saharan Arica.

Vaccines against the two leading bacterial causes o child pneumonia deaths, Haemophilus infuenzae type b (Hib) andStreptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), can urther improve child survival by preventing about 1 075 000 child deaths peryear. Both Hib and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines have proven saety and eectiveness or prevention o radiologically conrmedpneumonia in children, including in low-income and industrializing countries. Both are recommended by WHO or inclusion in nationalprogrammes, and, at sharply tiered prices, these vaccines generally meet international criteria o cost-eectiveness or low-incomecountries. Vaccines only target selected pneumonia pathogens and are less than 100% eective, so they must be complemented bycurative care and other preventative strategies.

As part o a comprehensive child survival package, the particular advantages o vaccines include the ability to reach a highproportion o all children, including those who are dicult to reach with curative health services, and the ability to rapidly scale up

coverage with new vaccines. In this review, we discuss advances made in optimizing the use o established vaccines and the potentialissues related to newer bacterial conjugate vaccines in reducing childhood pneumonia morbidity and mortality.

Bulletin o the World Health Organization 2008;86:365372.

Une traduction en ranais de ce rsum fgure la fn de larticle. Al fnal del artculo se acilita una traduccin al espaol. .

a Department o Science and Technology/National Research Foundation: Vaccine Preventable Diseases, University o the Witwatersrand, Chris Hani Baragwanth Hospital,Bertsham 2013, South Arica.

b Department o International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School o Public Health, Baltimore, MD, United States o America.c Health Section, United Nations Childrens Fund (UNICEF), New York, NY, USA.d Department o Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.Correspondence to Shabir A Madhi (e-mail: [email protected]).doi:10.2471/BLT.07.044503(Submitted: 3 October 2007 Revised version received: 15 January 2008 Accepted: 24 January 2008)

Introduction

Pneumonia is the commonest causeo childhood mortality, particularly incountries with the highest child mor-

tality, and it has been identied as themajor orgotten killer o children bythe United Nations Childrens Fund(UNICEF) and WHO.1 Almost all(99.9%) child pneumonia deaths oc-cur in developing and least developedcountries, with most occurring in sub-Saharan Arica (1 022 000 cases perannum) and South Asia (702 000 casesper annum). O all pneumonia deaths,47.7% occur in the least developedcountries,1 most o which are eligible toget support or the purchase o vaccinesand development o their immuniza-tion programmes through the GAVI

Alliance.2

Although various pathogens maycause pneumonia, either singly or incombination, the available evidence,including the eectiveness o case

management, suggests that two bacte-ria are the leading causes: Haemophilusinfuenzaetype b (Hib) and Streptococcus

pneumoniae (pneumococcus).3 WHO

estimates that in 2000, Hib and pneu-mococcus together accounted or morethan 50% o pneumonia deaths amongchildren aged 1 month to 5 years.4Several eective vaccines are avail-able or the prevention o childhoodpneumonia, including two vaccinesprovided in immunization programmesin all countries, Bordetella pertussisandmeasles vaccines, and two relativelynew vaccines, Hib conjugate vaccine(HibCV) and pneumococcal conjugatevaccines (PCVs).

In this paper, we aim to contextu-alize the potential role or vaccines aspart o a package o childhood inter-ventions, aimed at reducing childhoodpneumonia morbidity and mortality.

We summarize progress in the reduc-tion o childhood pneumonia mortal-ity with measles and pertussis vaccines;

review the eectiveness o newer bacte-rial conjugate vaccines against pneumo-nia; and discuss the potential hurdlesand likely solutions to ensure that

pneumonia vaccines reach the popula-tions at the greatest risk o pneumoniamortality.

Search strategy andselection criteria

We identied publications on the roleo bacterial conjugate vaccines againstpneumonia by searches o PubMed.Search terms included pneumococcalconjugate vaccine, Hib conjugate vac-cine, radiological pneumonia, bacte-

rial conjugate vaccine, radiograph,pneumonia, child, diagnosis andvaccine. Articles were selected on thebasis o their relevance to pneumoniaassessment in children. Te summary othe role o measles and pertussis vaccinesagainst pneumonia was sourced throughthe identication o key papers.

-

7/28/2019 07-044503

2/8

Special theme Prevention and control o childhood pneumonia

Vaccines to prevent pneumonia

366

Shabir A Madhi et al.

Bulletin o the World Health Organization | May 2008, 86 (5)

Control o pertussis andmeasles

Te last ew decades have seen remark-able progress in reduction o mortalitycaused by pertussis and measles. Eec-

tive inactivated whole-cell pertussisvaccines have been available since the1950s and are included in most immu-nization programmes worldwide. As aconsequence, WHO estimates that in2003, 38.3 million cases and 607 000deaths were prevented by the use opertussis vaccination.5 However, pertus-sis is still estimated to cause 295 000390 000 childhood deaths annually,

with most deaths in countries with lowimmunization rates and high mortalityrates.6 Further gains can be made by

increasing coverage with three doses odiphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine ininancy and the provision o boosterdoses as appropriate.

Te progress in reducing measlesmortality has been even greater. Pneu-monia as a complication ollowingmeasles inection occurs in 227% ochildren in community-based stud-ies and in 1677% o hospitalizedchildren.7 Additionally, pneumoniacontributes to 5686% o all deathsattributed to measles.7 Te pathogen-

esis may be due to the virus itsel or tosuperimposed viral or bacterial inec-tions occurring in 4755% o cases.7Pneumococcus is the most commonlyidentied organism (3050% o allmicrobiologically conrmed tests).8,9In 1980, beore the widespread useo measles vaccination in developingcountries, there were more than 2.5million deaths due to measles. Tisdeclined to about 873 000 deaths in1999.10 In 2001, a measles mortal-

ity reduction strategy was begun in47 priority countries with the highestdisease burden. Tis strategy consistedo increasing coverage with the rstroutine dose o measles vaccine, provi-sion o a second opportunity, throughsupplementary immunization activi-ties, appropriate case management andimproved surveillance. Te widespreadimplementation o this strategy, espe-cially in priority countries in Arica,led to a urther 60% reduction in theestimated measles deaths rom 873 000

in 1999 to 345 000 in 2005.11

A moreambitious global goal o 90% mortalityreduction, compared with that in theyear 2000, has been set or 2010.

HibCV and PCV eectiveness

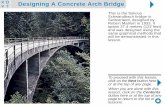

Since 1996, the eectiveness o HibCVand PCVs or the prevention o child-hood pneumonia has been establishedthrough eight clinical trials and threecasecontrol studies, and is backed bynumerous surveillance assessments(Fig. 1).1222

HibCV

Te rst studies to show the eective-ness o HibCV or prevention o pneu-monia were the randomized controlledtrials rom Chile and the Gambia.12,13Both studies showed signicant protec-tion against bacteraemic Hib pneumo-nia (80100%) and radiologically con-rmed pneumonia (about 22%). Tese

studies also showed that the incidenceo culture-negative pneumonia casesprevented was 5 to 10 times greater thanthe incidence o culture-conrmed casesprevented, supporting the observationsthat most bacterial pneumonia goes un-detected by routine diagnostic methodsand that vaccine trials are the most robustapproach to the estimation o the burdeno bacterial pneumonia.

More recently, additional clinicaltrials and casecontrol studies withHibCV have extended our knowledge

to other geographic regions. A random-ized controlled trial rom Lombok inIndonesia helped to uncover the burdeno Hib disease in Asia.14 However, thisstudy showed a signicant reduction inthe risk o clinical pneumonia but noreduction in the risk o radiologicallyconrmed pneumonia among vacci-nated compared with unvaccinatedchildren. Rates o clinical meningitispreventable by the vaccine were similarto rates observed in Arica and otherhigh-risk areas. Consistent with theother studies, the burden o pneu-monia prevented was about 10 timesgreater than the burden o meningitisprevented.

Casecontrol studies provideadditional evidence o the eective-ness o HibCV or prevention opneumonia.1921 A recent casecontrolstudy rom Bangladesh showed thatHib vaccination was associated with a3444% reduction in the risk o radio-logically conrmed pneumonia.21 In

this study, HibCV was distributed byuse o a quasi-randomized approachand adjustments were made or keyconounders. Estimates o high eec-

tiveness o vaccines against radiologi-cally conrmed pneumonia have alsobeen reported rom casecontrol stud-ies rom Brazil (31%) and Colombia(4755%).19,20

All o the studies that evaluated the

eectiveness o HibCV against pneu-monia used a primary series o threedoses o vaccine during inancy, albeitwith dierent starting age and intervalsbetween doses, and without an addi-tional booster dose o vaccine providedduring the second year o lie. Onlysome o the later studies used a stan-dardized approach or the interpreta-tion o chest radiographs, which makesit dicult to compare studies.

PCVs

PCVs provide another eective methodor pneumonia prevention in childrenand their amilies. Data are currentlyavailable rom ve randomized con-trolled trials o PCVs or preventiono pneumonia in children. 1518,22Te comparison o studies is acilitatedby the act that each study used astandard interpretation o chest ra-diographs.23 All children in each studyreceived HibCV so the proportionatereductions in radiologically conrmedpneumonia were in addition to preven-

tion due to HibCV. Te two studies inthe United States o America (USA)used seven-valent vaccine, and the twoin Arica used a nine-valent vaccine andan 11-valent ormulation was used inthe Philippines. Te studies representa diverse range o epidemiological set-tings including rural Arica with a highinant mortality rate, urban Arica witha high HIV prevalence, periurban Asiawith a high rate o antibiotic use, a Na-tive American and a typical Americanhealth-maintenance-organization

population. Tese studies oundreductions (2037%) o radiologi-cally conrmed pneumonia thatconrmed the importance o thepneumococcal vaccine serotypes asa cause o pneumonia. 1517,22 LikeHibCV, the large raction o prevent-able disease is undetected by routinediagnostic methods. Te ecacy oPCVs against vaccine-serotype bacter-aemic pneumonia is high (6787%),15,16but comparisons to the incidenceo X-ray conrmed pneumonia or

clinical pneumonia show that up to20 times more culture-negative casesare prevented compared with culturepositive cases.24

-

7/28/2019 07-044503

3/8

Special theme Prevention and control o childhood pneumonia

Vaccines to prevent pneumonia

367

Shabir A Madhi et al.

Bulletin o the World Health Organization | May 2008, 86 (5)

Fig. 1. Global distribution o PCV and HibCV studies against radiologically conrmed pneumoniaa,b

Navajo, USA (rural)(K OBrien, personal

correspondence)American Indians

PCV-7 cluster randomizedVE: 2%; P> 0.05

Northern Caliornia,USA15

PCV-7 DBRCTVE: 30%; 95% CI: 1146

Colombia (urban)20

HibCV casecontrol studyVE: 55%; 95% CI: 778

Chile (urban)13

HibCV RCT (retrospective)VE: 22%; 95% CI: 743;

VAR: 1.1

Brazil (urban)19

HibCV casecontrol studyVE: 31%; 95% CI: 957

South Arica (urban)16

PCV-9 DBRCTHIV inected children:

VE: 9%; 95% CI: 1527;VAR: 9.1

HIV non-inected children:VE: 25%; 95% CI: 440;

VAR: 1.0

Indonesia (rural)14

HibCV DBRCTVE: 12%; P> 0.05

Philippines (rural)22

PCV-11 DBRCTVE: 22.9%;

95% CI: 141

Bangladesh (urban)21

HibCV casecontrol studyVE hospital controls:34%; 95% CI: 644;

VE community controls:44%; 95% CI: 2061

The Gambia (semi-urban)12

HibCV DBRCTVE: 22%; 95% CI: 239;

VAR: 0.8

The Gambia (rural)17

PCV-9 DBRCTVE: 35%; 95% CI: 2643;

VAR: 14.9

CI, condence interval ; DBRCT, double-blind randomized controlled tria l; HibCV, Haemophilus infuenzaetype b conjugate vaccine; PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; USA,United States o America; VAR, vaccine attributable reduction per 1000 child years o observation; VE, vaccine ecacy based against radiologically conrmed pneumonia by useo per-protocol analysis when available.a All the studies evaluating PCV, as well as the HibCV studies in Indonesia and Bangladesh, used the WHO recommendations or interpreting and reporting on chest radiographs.23b The study rom Colombia used an algorithm score which included radiologically conrmed pneumonia as one o the criteria.

Te use o a case-denition thatis not specic or vaccine serotypedisease (e.g. radiologically conrmedpneumonia, which can also be due tonon-vaccine serotype pneumococci orother pathogens) will provide a more

accurate estimate o the number ocases prevented, but may underesti-mate the proportionate reduction invaccine-type pneumococcal pneu-monia.25 Radiologically conrmedpneumonia, although consistently usedas an outcome measure to assess PCVecacy, may nevertheless vary in itssensitivity (76.5% in the Gambia versus58.1% in South Arica) across diversesettings.17,24 In the USA, 3 years aterPCV introduction, a 39% (95% con-dence interval, CI: 2252) reduction

in pneumonia hospitalizations amongchildren less than 2 years old was ob-served.26 Te absolute rate reduction orclinical pneumonia was 30 times greater

than the reduction in pneumococcalpneumonia (506 versus 17 episodesprevented per 100 000 child-years)as per physician discharge diagnosis,again highlighting the diculties in thediagnosis o pneumococcal pneumo-

nia, even in industrialized countries,and the substantial eect o vaccinationthat can be missed by culture-baseddiagnoses. Te higher than expected de-cline in clinical pneumonia in the USA,ater the introduction o PCV, mayhave been due to PCV preventing thecomplication o a superimposed pneu-mococcal inection in children who hadbeen inected by respiratory viruses.Such superimposed pneumococcal dis-ease in children with respiratory viralinections was prevalent in almost a

third o children hospitalized with se-vere pneumonia in the prevaccine era.27

Te important role o pneumococ-cus in children with viral pneumonia

was demonstrated in the South Aricanvaccine ecacy trial, in which childrenvaccinated with nine-valent PCV were31% (95% CI: 1543) less likely to behospitalized or pneumonia in which arespiratory virus was identied, includ-

ing 45% (95% CI: 1464) less likely to behospitalized with pneumonia associatedwith infuenza type A/B viruses.28 Vacci-nation o children with PCV may play animportant part in reducing the severityo respiratory viral associated pneumoniamorbidity as well as in preparedness ora uture infuenza pandemic, becausepneumococcal pneumonia commonlyollows infuenza illness.29 Unlike Hibdisease, which aects mainly childrenless than 2 years o age, pneumococ-cal disease also occurs among older

children and adults. As a consequence,PCV immunization o children mayconer protection to unvaccinated popu-lations through herd protection.30,31

-

7/28/2019 07-044503

4/8

Special theme Prevention and control o childhood pneumonia

Vaccines to prevent pneumonia

368

Shabir A Madhi et al.

Bulletin o the World Health Organization | May 2008, 86 (5)

In the USA, this indirect eect o vacci-nation has prevented two to three timesas many cases o invasive pneumococcaldisease as through the direct eect o vac-cinating young children.32 Te indirecteect is probably the cause o the 26%

(95% CI: 443) reduction in pneumo-nia hospitalizations among those aged1839 years, 3 years ater introductiono seven-valent PCV in the USA.26

Surveillance or culture-proveninvasive disease is valuable because itprovides the only opportunity to moni-tor the eectiveness o vaccine againstspecic serotypes and to detect changesin the distribution o serotypes causingdisease. In the USA, the experience withnon-vaccine serotype disease has variedacross populations rom the general

population where, ater 6 years, increasesin non-vaccine-type disease are observed,but remain small in relation to the declinein vaccine-type disease compared withindigenous populations in rural Alaska,

which have high rates o non-vaccine-typedisease 35 years ater vaccine use.32,33Serotype replacement in nasopharyngealcolonization and otitis media has beenobserved previously.34 Te most robustevidence o the value o PCVs or improv-ing child survival comes rom a trial inthe Gambia in which nine-valent PCVreduced all-cause mortality by 16% (95%CI: 328) in vaccine recipients an ab-solute reduction o 7.4 deaths preventedper 1000 vaccinated children.17

On the basis o disease burdenand the proven eectiveness o HibCVand PCV in diverse settings, WHOrecommends the inclusion o botho these vaccines in routine immu-nization programmes.22,35 ogether,HibCV and PCV, i applied every-

where, are expected to prevent at least

1 075 000 child deaths each year pre-dominantly in developing countries,and with herd protection additionalcases and deaths in older age groups.4

Infuenza vaccines

Recent advances in the development ointranasal cold-adapted live-attenuatedinfuenza vaccines hold potential orthe reduction o childhood infuenza.36Te eect o infuenza vaccine has beencontroversial, with one meta-analysis

suggesting relatively low eectivenessand limited data or children less than2 years o age.37 A more recent analy-sis has suggested that methodological

problems with some studies have ledto underestimates o infuenza vaccineecacy in children.38 Nevertheless, as

with subunit infuenza vaccines, whichmay prevent 87% o infuenza associ-ated pneumonia hospitalizations,39

eective vaccination against infuenzais dependent on the match betweenthe strains included in the vaccine andcirculating strains during any epidemic.Te inclusion o infuenza vaccinationas a current strategy or the reductiono childhood pneumonia in many de-veloping countries is complicated bythe need to mobilize children or vac-cination seasonally, logistical issues ocold-chain storage o the live-attenuatedvaccines, concerns regarding its reacto-genicity in very young inants, and the

need or revaccination each year.

HIV inection and vaccination

Although chi ldren with HIV com-prise less than 5% o the childhoodpopulation, even in heavily-burdenedsub-Saharan Arican countries, thesechildren suer disproportionately rompneumonia (nine times greater risk) andare susceptible to pneumonia causedby a greater variety o pathogens.24,40In South Arica, HIV-inected children

account or 45% o all childhood pneu-monia morbidity and 90% o pneumo-nia mortality.24,41 Tis high disease riskand broader array o causes complicatesdiagnosis and treatment and increasesthe importance o prevention. Data onHibCV and PCV in children inected

with HIV show no saety concerns. Teimmune responses to HibCV and PCVare, however, reduced quantitativelyand qualitatively attenuated. Antibodytitres are maintained or a shorter

duration, and memory responses areimpaired compared with HIV non-inected children.4245 Suboptimumimmune responses (2575%) have alsobeen observed against measles vaccinein children with HIV not on antiret-roviral drugs.46 For vaccinations ingeneral, reviews o the saety, immuno-genicity and eectiveness data o child-hood vaccines in HIV-inected childrenhave recently shown that the responseto vaccines is strongly aected by theuse o antiretroviral drugs.46 For ex-

ample, immune responses to PCV inchildren with HIV on antiretroviraltherapy are similar to those in childrennot inected by HIV.47

PCV and HibCV are less eectiveagainst invasive disease in childrenwith HIV not treated with antiretro-viral drugs (65% and 54%, respec-tively), compared with children withoutHIV (83% and 90%, respectively).16,48

Nevertheless, because o a 2040 timesincreased risk o illness rom these bac-teria, HIV-inected children still derivea signicant protective eect and theabsolute burden o invasive disease andpneumonia prevented by the vaccinesexceeds that o HIV non-inected chil-dren.16,48 Within this context WHO hasrecommended that countries with a highprevalence o HIV prioritize the intro-duction o PCV into their immunizationprogrammes.21

Future vaccines

Although currently available vaccinescan prevent most pneumonia deaths inchildren, additional research is neededto dene the cause o the remainingcases o pneumonia and to develop vac-cines against these pathogens. Te nextagent preventable by vaccination maybe non-typeable H. infuenzae. A newpneumococcal conjugate vaccine thatuses H. infuenzaeprotein-D as a con-jugate protects against acute otitis media

caused by H. infuenzae,49 and is cur-rently being assessed or eectivenessagainst pneumococcal and H. infuenzaepneumonia. Non-typeable H. infuenzaeis a pneumonia pathogen in Asia.50

Other pathogens or which vac-cines are currently being developedinclude respiratory syncytial virus,51which is the most common viral patho-gen (2535%) identied in childrenwith pneumonia and bronchiolitis,52,53and parainfuenza virus type 3.54 Addi-

tionally, improved vaccines to protectagainst pulmonary tuberculosis mayalso contribute to the control o theperpetual epidemic o childhood pneu-monia. Mycobacterium tube rculos iscauses pneumonia in about 8% o HIV-inected and HIV non-inected childrenhospitalized with severe pneumonia insub-Saharan Arican countries.55,56

Cost-eectiveness

Childhood vaccination is widely re-

garded as one o the most cost-eectivedisease prevention interventions.57Numerous studies show that routinevaccination in developing countries

-

7/28/2019 07-044503

5/8

Special theme Prevention and control o childhood pneumonia

Vaccines to prevent pneumonia

369

Shabir A Madhi et al.

Bulletin o the World Health Organization | May 2008, 86 (5)

with HibCV, PCV, pertussis vaccineand measles vaccine meet the criteriaor highly cost-eective health interven-tions over a range o plausible assump-tions related to ecacy, price and diseaseburden. A recent review o intervention

packages by Laxminarayan et al.57

showsthat programmes o childhood im-munization and control o pneumoniamortality in children are highly cost-eective. Te review shows a moderatecost-eectiveness o Hib containingvaccines. Laxminarayan et al. did notreport a cost-eectiveness or PCV, buta recent cost-eectiveness analysis opneumococcal vaccination in countriescovered by the GAVI Alliance estimatedthat, at a price o US$ 5 per dose, apneumococcal vaccine programme

would meet or exceed the WHO thresh-old or very cost-eective in 69 o the72 eligible countries.58 Tese ndings

were conservative in the sense that theydid not assume any herd protectionamong unvaccinated children or adultsand did not assume any direct pro-tection beyond the age o 2.5 years,although current evidence wouldsuggest that both o these benets arelikely. Previous cost-eectiveness stud-ies o HibCV and PCVs or developingcountries had similar results.59

Advantages

Newer vaccines to prevent pneumo-nia can be delivered through existingimmunization programmes, whichin 2006 provided a third dose odiphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine toabout 79% o the worlds birth cohort(WHO/IVB database). While vaccinesonly cover a ew specic pathogens andonly selected serotypes o some o the

pathogens targeted, immunization hasseveral other advantages that make it ahighly eective tool or disease control.Immunization coners durable, long-lasting protection, it requires only aew contacts to coner that protection,is rapidly scalable and capable o reach-ing populations who are hard to reachthrough curative health services. Expe-rience with introduction o hepatitisB vaccine and HibCV has shown thatcoverage with these vaccines can rapidlybe increased to the same levels as a third

dose o diphtheria-tetanus-pertussisvaccine. Even when these vaccines were

not delivered in combination withdiphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccinesand where the introduction was phased

within the country, coverage rates closeto those o a third dose o diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine were achieved

in most countries in 3 to 5 years. Incountries where combination vaccineswere introduced nationwide, coveragerates immediately increased to thoseo a third dose o diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine.

Tus, vaccines can rapidly reach ahigh proportion o the population andquickly lower disease rates. For somediseases, herd protection can extendthe benet o childhood vaccination toother age groups as well, an advantagethat ew other interventions can match.

For both HibCV and PCV, the useo regimens with three doses given ininancy is eective, and current pro-grammes in much o Arica and else-

where do not include routine deliveryo immunizations in the second year olie (i.e. booster immunizations),although close monitoring o disease isrequired to determine the need or ad-ditional doses in these settings.

Financing options

For many years, relatively high pricesand limited, short-term purchasingnance obstructed the use o new vac-cines in many developing countries.

With the creation o the GAVI Alli-ance in 2000, nancing or the poorestcountries to access vaccines improvedgreatly. Te alliance started by provid-ing countries with up to 5 years oguaranteed nancing or vaccine pro-curement and strengthening o immu-nization systems. Financing included

support or expansion o vaccines topertussis and measles, and or the pur-chase o HibCV. In 2005, the GAVI

Alliance had its unding extended or10 years, and in recent years has seen itstotal commitments increase rom aboutUS$ 750 million to over US$ 6 billion.Tis increase in unding includes morethan US$ 500 million or strengthen-ing health systems and US$ 1.5 billionor the purchase o PCVs through aninnovative mechanism known as the

Advance Market Commitment. o

build national ownership and encour-age evidence-based decisions, the GAVI

Alliance requires a small co-payment(currently between US$ 0.15 and US$0.30 per dose) rom countries or newvaccines such as HibCV and PCV. Earlyexperience with HibCV and hepatitis Bvaccines showed that overcoming the

nancial obstacles was necessary, butnot sucient, to accelerate introduc-tion. Te lack o evidence and policiesto support decision-making in countrieswas also a major obstacle. In response,the GAVI Alliance also provided solu-tions by creating the PneumococcalVaccines Accelerated Developmentand Introduction Project and the HibInitiative. Tese dedicated teams pro-vide support or surveillance, research,cost-eectiveness analyses and otheractivities to encourage better decisions

by GAVI Alliance partners, interna-tional agencies and national govern-ments. Te progress in assuring accessor low-income countries through theGAVI Alliance has not been matchedby progress in lower-middle-incomecountries. Some large countries withincome levels just above the limitor GAVI Alliance-eligibility, such asEgypt and the Philippines, have manychildren living in poverty but lack thenational nancing to access new vac-

cines on their own. Without addi-tional eorts to assure access or thesecountries, it will be dicult to avoid asituation o bimodal access to new vac-cines, in which the richest and poorestcountries have access but those in themiddle are let to lag years behind.

The road ahead

Existing and new pneumonia vaccinesare an important part o any package orthe control o pneumonia in childhood.

Indeed, each o the vaccines reviewedhere is recommended by WHO or inclu-sion in national programmes. With new,sustained nancing available to manydeveloping countries, a major obstacle tothe use o new vaccines has been largelyovercome and the expanded use o allpneumonia vaccines is largely withinreach o low-income countries. Althoughthe road ahead is smoother than beore, agreat deal remains to be done. Success willrequire political will to make pneumoniaprevention a priority, strengthening o

health systems to assure that vaccinesreach all children and continued research

-

7/28/2019 07-044503

6/8

Special theme Prevention and control o childhood pneumonia

Vaccines to prevent pneumonia

370

Shabir A Madhi et al.

Bulletin o the World Health Organization | May 2008, 86 (5)

Rsum

Vaccins destins prvenir la pneumonie et amliorer la survie des enantsDepuis plus de 30 ans, les vaccins jouent un rle important dansla prvention de la pneumonie. Des progrs rcents ont gnrdes opportunits damliorer encore la survie des enants travers la prvention par la vaccination des pneumonies inantiles.La dlivrance au plus grand nombre possible des vaccinationsanticoquelucheuse et antirougeoleuse systmatiques, associe lore dune seconde opportunit de vaccination contre la rougeole,ont permis de rduire rapidement la mortalit chez lenant dans les

pays aible revenu, et notamment en Arique subsaharienne.Les vaccins contre les deux principales causes de

mortalit inantile par pneumonie, savoir les bactriesHaemophilus infuenzaetype b (Hib) et Streptococcus pneumoniae(pneumocoque), peuvent permettre daccrotre encore la surviedes enants, en prvenant environ 1 075 000 dcs inantilespar an. Les vaccins anti-Hib et antipneumococcique conjugusont tous deux ait la preuve de leur innocuit et de leur ecacitdans la prvention des pneumonies radiologiquement conrmeschez lenant, et notamment dans les pays aible revenu et en

cours dindustrialisation. LOMS recommande dintroduire dansles programmes nationaux de vaccination ces deux vaccinsqui, moyennant une orte modulation de leur prix, remplissentgnralement les critres internationaux de rapport cot/ecacitpour les pays aible revenu. Touteois, ils visent slectivementcertains pathognes lorigine de pneumonies et ne sont pasecaces 100 %, de sorte quils doivent tre complts par des soinscuratis et par dautres stratgies de prvention.

Dans le cadre dun ensemble complet dinterventionspour la survie de lenant, ces vaccins orent lavantage depouvoir atteindre une orte proportion des enants, y comprisceux diciles toucher par les services de sant curatis, et depermettre un largissement rapide de la couverture desnouveaux vaccins. Dans cette tude, nous examinons lesprogrs raliss vers un usage optimal des vaccins tablis etles problmes que pourrait soulever lutilisation de vaccinsantibactriens conjugus plus rcents pour rduire la morbiditet la mortalit par pneumonie chez lenant.

ResumenVacunas para prevenir la neumona y mejorar la supervivencia inantilDurante ms de 30 aos las vacunas han sido un armaundamental para la prevencin de la neumona. Algunosprogresos recientes han brindado nuevas oportunidades paraseguir mejorando la supervivencia inantil previniendo laneumona en la niez mediante vacunacin. La optimizacin dela inmunizacin sistemtica con las vacunas antitoserinosa yantisarampionosa, unida a la implementacin de una segundaoportunidad para la inmunizacin contra el sarampin, hareducido rpidamente la mortalidad en la niez en los pases deingresos bajos, sobre todo del rica subsahariana.

Las vacunas contra las dos causas bacterianas principales

de muerte por neumona en la inancia, Haemophilus infuenzaetipo b (Hib) y Streptococcus pneumoniae (neumoccico), puedenmejorar an ms la supervivencia inantil previniendo alrededorde 1 075 000 deunciones inantiles cada ao. Las vacunasconjugadas contra Hib y contra el neumococo han demostrado suseguridad y ecacia en la prevencin de la neumona conrmadaradiolgicamente en los nios, tanto en los pases de bajos

ingresos como en los nuevos pases industrializados. La OMSrecomienda la inclusin de ambas en los programas nacionales,y a precios uertemente escalonados estas vacunas satisacenen general los criterios internacionales de costoecacia paralos pases de ingresos bajos. Las vacunas actan slo contraalgunos de los agentes patgenos causantes de neumona ysu ecacia es inerior al 100%, de modo que requieren comocomplemento atencin curativa y otras estrategias de prevencin.

Componente de un paquete integral de supervivenciainantil, las vacunas presentan como ventajas particulares laposibilidad de dar alcance a un alto porcentaje de nios, incluidos

aquellos a los que los servicios de salud curativos slo consiguenllegar con grandes dicultades, y la posibilidad de expandirrpidamente la cobertura con vacunas nuevas. En este anlisisconsideramos los avances logrados para optimizar el uso delas vacunas establecidas y las cuestiones que pueden plantearlas nuevas vacunas antibacterianas conjugadas en lo tocante areducir la morbilidad y la mortalidad inantiles por neumona.

to stay ahead o the bacteria and virusesthat are already vaccine preventable and todevelop new technologies or preventingthose without vaccines. Expanded sur-veillance that allows countries to monitorthe eect o vaccines and to adapt their

programmes to respond to changes is alsoneeded.

AcknowledgementWe thank Peter Strebel or his review othe measles section o the manuscript.

Competing interests: Shabir A Madhireceived research-grant support andserved on the speakers bureau or WyethVaccines and Pediatrics. Te otherauthors do not declare any competinginterests.

.

..

-

7/28/2019 07-044503

7/8

Special theme Prevention and control o childhood pneumonia

Vaccines to prevent pneumonia

371

Shabir A Madhi et al.

Bulletin o the World Health Organization | May 2008, 86 (5)

Reerences

Pneumonia: the orgotten killer o children1. . Geneva: UNICEF/WHO; 2006.Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying2.every year? Lancet2003;361:2226-34. PMID:12842379doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8

Sazawal3. S, Black RE. Eect o pneumonia case management on mortality inneonates, inants, and preschool children: a meta-analysis o community-based trials. Lancet Inect Dis2003;3:547-56. PMID:12954560doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00737-0Vaccine4. preventable deaths and the global immunization vision and strategy,2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep2006;55:511-5. PMID:16691182Pertussis5. vaccines WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec2005;80:31-9.PMID:15717398Crowcrot6. NS, Stein C, Duclos P, Birmingham M. How best to estimate theglobal burden o pertussis? Lancet Inect Dis2003;3:413-8. PMID:12837346doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00669-8Duke7. T, Mgone CS. Measles: not just another viral exanthem. Lancet2003;361:763-73. PMID:12620751doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12661-XMorton8. R, Mee J. Measles pneumonia: lung puncture ndings in 56 casesrelated to chest X-ray changes and clinical eatures.Ann Trop Paediatr1986;

6:41-5. PMID:2428292Quiambao9. BP, Gatchal ian SR, Halonen P, Lucero M, Sombrero L, Paladin FJ,et al. Co-inection is common in measles-associated pneumonia. PediatrInect Dis J1998;17:89-93. PMID:9493801doi:10.1097/00006454-199802000-00002Progress10. in reducing global measles deaths, 1999-2004. MMWR MorbMortal Wkly Rep2006;55:247-9. PMID:16528234Wolson11. LJ, Strebel PM, Gacic-Dobo M, Hoekstra EJ, McFarland JW, Hersh BS.Has the 2005 measles mortality reduction goal been achieved? A naturalhistory modelling study.Lancet2007;369:191-200. PMID:17240285doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60107-XMulholland12. K, Hilton S, Adegbola R, Usen S, Oparaugo A, Omosigho C, et al.Randomised trial o Haemophilus infuenzae type-b tetanus protein conjugatevaccine. Lancet1997;349:1191-7. PMID:9130939doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09267-7

Levine13. OS, Lagos R, Munoz A, Villaroel J, Alvarez AM, Abrego P, et al. Deningthe burden o pneumonia in children preventable by vaccination againstHaemophilus infuenzae type b. Pediatr Inect Dis J1999;18:1060-4.PMID:10608624doi:10.1097/00006454-199912000-00006Gessner14. BD, Sutanto A, Linehan M, Djelantik IG, Fletcher T, Gerudug IK, et al.Incidences o vaccine-preventable Haemophilus infuenzae type b pneumoniaand meningitis in Indonesian children: hamlet-randomised vaccine-probetrial. Lancet2005;365:43-52. PMID:15643700doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17664-2Hansen15. J, Black S, Shineeld H, Cherian T, Benson J, Fireman B, et al.Eectiveness o heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in childrenyounger than 5 years o age or prevention o pneumonia: updatedanalysis using World Health Organization standardized interpretation ochest radiographs. Pediatr Inect Dis J2006;25:779-81. PMID:16940833doi:10.1097/01.in.0000232706.35674.2

Klugman16. KP, Madhi SA, Huebner RE, Kohberger R, Mbelle N, Pierce N. A trialo a 9-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children with and thosewithout HIV inection. N Engl J Med2003;349:1341-8. PMID:14523142doi:10.1056/NEJMoa035060

Cutts17. FT, Zaman SM, Enwere G, Jaar S, Levine OS, Okoko JB, et al. Ecacyo nine-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against pneumonia andinvasive pneumococcal disease in the Gambia: randomised, double-blind,placebo-controlled trial. Lancet2005;365:1139-46. PMID:15794968

doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71876-6O18. Brien KL, Moulton LH, Reid R, Weatherholtz R, Oski J, Brown L, et al.Ecacy and saety o seven-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine inAmerican Indian children: group randomised trial. Lancet2003;362:355-61.PMID:12907008doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14022-6de19. Andrade AL, de Andrade JG, Martelli CM, e Silva SA, de Oliveira RM,Costa MS, et al. Eectiveness o Haemophilus infuenzae b conjugate vaccineon childhood pneumonia: a case-control study in Brazil. Int J Epidemiol2004;33:173-81. PMID:15075166doi:10.1093/ije/dyh025de20. la Hoz F, Higuera AB, Di Fabio JL, Luna M, Naranjo AG, de la Luz Valencia M,et al. Eectiveness o Haemophilus infuenzae type b vaccination againstbacterial pneumonia in Colombia. Vaccine2004;23:36-42. PMID:15519705doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.05.017Baqui21. AH, El Arieen S, Saha SK, Persson L, Zaman K, Gessner BD, et al.Eectiveness o Haemophilus infuenzae type b conjugate vaccine on

prevention o pneumonia and meningitis in Bangladeshi children: a case-control study. Pediatr Inect Dis J2007;26:565-71. PMID:17596795doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e31806166a0Pneumococcal22. conjugate vaccine or childhood immunization WHO positionpaper. 22. Wkly Epidemiol Rec2007;82:93-104. PMID:17380597Cherian23. T, Mulhol land EK, Carlin JB, Ostensen H, Amin R, de Campo M,et al. Standardized interpretation o paediatric chest radiographs or thediagnosis o pneumonia in epidemiological studies. Bull World Health Organ2005;83:353-9. PMID:15976876Madhi24. SA, Kuwanda L, Cutland C, Klugman KP. The impact o a 9-valentpneumococcal conjugate vaccine on the public health burden o pneumoniain HIV-inected and -uninected children. Clin Inect Dis2005;40:1511-8.PMID:15844075doi:10.1086/429828Madhi25. SA, Klugman KP. World Health Organisation denition o radiologically-conrmed pneumonia may under-estimate the true public health

value o conjugate pneumococcal vaccines. Vaccine2007;25:2413-9.PMID:17005301doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.010Grijalva26. CG, Nuorti JP, Arbogast PG, Martin SW, Edwards KM, Grin MR.Decline in pneumonia admissions ater routine childhood immunisation withpneumococcal conjugate vaccine in the USA: a time-series analysis. Lancet2007;369:1179-86. PMID:17416262doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60564-9Michelow27. IC, Olsen K, Lozano J, Rollins NK, Duy LB, Ziegler T, et al.Epidemiology and clinical characteristics o community-acquired pneumoniain hospitalized children. Pediatrics2004;113:701-7. PMID:15060215doi:10.1542/peds.113.4.701Madhi28. SA, Klugman KP. A role or Streptococcus pneumoniae in virus-associated pneumonia. Nat Med2004;10:811-3. PMID:15247911doi:10.1038/nm1077Klugman29. KP, Madhi SA. Pneumococcal vaccines and fu preparedness.Science2007;316:49-50. PMID:17412937 doi:10.1126/

science.316.5821.49cKlugman30. KP. Ecacy o pneumococcal conjugate vaccines and their eecton carriage and antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Inect Dis2001;1:85-91.PMID:11871480doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00063-9

. 1075 000

.

.

%100.

.

.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12842379&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12954560&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00737-0http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16691182&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15717398&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12837346&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00669-8http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12620751&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12661-Xhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=2428292&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=9493801&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199802000-00002http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199802000-00002http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16528234&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17240285&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60107-Xhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=9130939&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09267-7http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09267-7http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10608624&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199912000-00006http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15643700&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17664-2http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17664-2http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16940833&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000232706.35674.2fhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=14523142&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa035060http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15794968&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71876-6http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12907008&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14022-6http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15075166&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh025http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15519705&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.05.017http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17596795&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/INF.0b013e31806166a0http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17380597&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15976876&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15844075&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1086/429828http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17005301&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.010http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17416262&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60564-9http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15060215&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.4.701http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15247911&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nm1077http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17412937&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.316.5821.49chttp://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.316.5821.49chttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11871480&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00063-9http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00063-9http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11871480&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.316.5821.49chttp://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.316.5821.49chttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17412937&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nm1077http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15247911&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.4.701http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15060215&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60564-9http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17416262&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.010http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17005301&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1086/429828http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15844075&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15976876&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17380597&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/INF.0b013e31806166a0http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17596795&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.05.017http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15519705&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh025http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15075166&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14022-6http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12907008&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71876-6http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15794968&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa035060http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=14523142&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000232706.35674.2fhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16940833&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17664-2http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17664-2http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15643700&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199912000-00006http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10608624&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09267-7http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09267-7http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=9130939&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60107-Xhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17240285&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16528234&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199802000-00002http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199802000-00002http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=9493801&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=2428292&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12661-Xhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12620751&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00669-8http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12837346&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15717398&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16691182&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00737-0http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12954560&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12842379&dopt=Abstract -

7/28/2019 07-044503

8/8

Special theme Prevention and control o childhood pneumonia

Vaccines to prevent pneumonia

372

Shabir A Madhi et al.

Bulletin o the World Health Organization | May 2008, 86 (5)

Whitney31. CG, Farley MM, Hadler J, Harrison LH, Bennett NM, Lyneld R,et al. Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease ater the introduction oprotein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. N Engl J Med2003;348:1737-46.PMID:12724479doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022823Direct32. and indirect eects o routine vaccination o children with 7-valentpneumococcal conjugate vaccine on incidence o invasive pneumococcaldisease United States, 1998-2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep2005;54:893-7. PMID:16163262Singleton33. RJ, Hennessy TW, Bulkow LR, Hammitt LL, Zulz T, Hurlburt DA, et al.Invasive pneumococcal disease caused by nonvaccine serotypes amongAlaska native children with high levels o 7-valent pneumococcal conjugatevaccine coverage. JAMA 2007;297:1784-92. PMID:17456820doi:10.1001/

jama.297.16.1784Eskola34. J, Kilpi T, Palmu A, Jokinen J, Haapakoski J, Herva E, et al. Ecacy oa pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against acute otitis media. N Engl J Med2001;344:403-9. PMID:11172176doi:10.1056/NEJM200102083440602WHO35. position paper on Haemophilus infuenzae type b conjugate vaccines(Replaces WHO position paper on Hib vaccines previously published in theWeekly Epidemiological Record). Wkly Epidemiol Rec2006;81:445-52.PMID:17124755Piedra36. PA, Gaglani MJ, Kozinetz CA, Herschler GB, Fewlass C, Harvey D, et al.Trivalent live attenuated intranasal infuenza vaccine administered during the

2003-2004 infuenza type A (H3N2) outbreak provided immediate, direct, andindirect protection in children. Pediatrics2007;120:e553-64. PMID:17698577doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2836Smith37. S, Demicheli V, Di Pietrantonj C, Harnden AR, Jeerson T, Matheson NJ,et al. Vaccines or preventing infuenza in healthy children. Cochrane DatabaseSyst Rev2006;1:CD004879. PMID:16437500Manzoli38. L, Schioppa F, Boccia A, Villar i P. The ecacy o infuenza vaccine orhealthy children: a meta-analysis evaluating potential sources o variation inecacy estimates including study quality. Pediatr Inect Dis J2007;26:97-106. PMID:17259870doi:10.1097/01.in.0000253053.01151.bdAllison39. MA, Daley MF, Crane LA, Barrow J, Beaty BL, Allred N, et al. Infuenzavaccine eectiveness in healthy 6- to 21-month-old children duringthe 2003-2004 season. J Pediatr2006;149:755-62. PMID:17137887doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.06.036Graham40. SM, Gibb DM. HIV disease and respiratory inection in children. Br

Med Bull2002;61:133-50. PMID:11997303doi:10.1093/bmb/61.1.133Zwi41. KJ, Pettior JM, Soderlund N. Paediatric hospital admissions at a SouthArican urban regional hospital: the impact o HIV, 1992-1997.Ann TropPaediatr1999;19:135-42. PMID:10690253 doi:10.1080/02724939992455Gibb42. D, Spolou V, Giacomel li A, Griths H, Masters J, Misbah S, et al.Antibody responses to Haemophilus infuenzae type b and Streptococcuspneumoniae vaccines in children with human immunodeciency virusinection. Pediatr Inect Dis J1995;14:129-35. PMID:7746695Madhi43. SA, Kuwanda L, Cutland C, Holm A, Kayhty H, Klugman KP. Quanti tativeand qualitative antibody response to pneumococcal conjugate vaccine amongArican human immunodeciency virus-inected and uninected children.Pediatr Inect Dis J2005;24:410-6. PMID:15876939doi:10.1097/01.in.0000160942.84169.14Gibb44. D, Giacomelli A, Masters J, Spoulou V, Ruga E, Griths H, et al.Persistence o antibody responses to Haemophilus infuenzae type b

polysaccharide conjugate vaccine in children with vertically acquired humanimmunodeciency virus inection. Pediatr Inect Dis J1996;15:1097-101.PMID:8970219doi:10.1097/00006454-199612000-00008Madhi45. SA, Kuwanda L, Saarinen L, Cutland C, Mothupi R, Kyhty H, et al.Immunogenicity and eectiveness o Haemophilus infuenzae type bconjugate vaccine in HIV inected and uninected Arican children. Vaccine2005;23:5517-25. PMID:16107294doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.038

Obaro46. SK, Pugatch D, Luzuriaga K. Immunogenicity and ecacy o childhoodvaccines in HIV-1-inected children. Lancet Inect Dis2004;4:510-8.PMID:15288824doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01106-5Abzug47. MJ, Pelton SI, Song LY, Fenton T, Levin MJ, Nachman SA, et al.Immunogenicity, saety, and predictors o response ater a pneumococcalconjugate and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine series in humanimmunodeciency virus-inected children receiving highly activeantiretroviral therapy. Pediatr Inect Dis J2006;25:920-9. PMID:17006288doi:10.1097/01.in.0000237830.33228.c3Madhi48. SA, Petersen K, Khoosal M, Huebner RE, Mbelle N, Mothupi R, etal. Reduced eectiveness o Haemophilus infuenzae type b conjugatevaccine in children with a high prevalence o human immunodeciency virustype 1 inection. Pediatr Inect Dis J2002;21:315-21. PMID:12075763doi:10.1097/00006454-200204000-00011Prymula49. R, Peeters P, Chrobok V, Kriz P, Novakova E, Kaliskova E, et al.Pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides conjugated to protein D orprevention o acute otitis media caused by both Streptococcus pneumoniaeand non-typable Haemophilus infuenzae: a randomised double-blind ecacystudy. Lancet2006;367:740-8. PMID:16517274 doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68304-9Shann50. F. Haemophilus infuenzae pneumonia: type b or non-type b? Lancet1999;354:1488-90. PMID:10551490doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00232-9

Wright51. PF, Karron RA, Belshe RB, Thompson J, Crowe JE Jr, Boyce TG, et al.Evaluation o a live, cold-passaged, temperature-sensitive, respiratorysyncytial virus vaccine candidate in inancy.J Inect Dis2000;182:1331-42.PMID:11010838doi:10.1086/315859Law52. BJ, Carbonell-Estrany X, Simoes EA. An update on respiratory syncytialvirus epidemiology: a developed country perspective. Respir Med2002;96Suppl B;S1-7. PMID:11996399Simoes53. EA. Respiratory syncytial virus inection. Lancet1999;354:847-52.PMID:10485741Belshe54. RB, Newman FK, Tsai TF, Karron RA, Reisinger K, Roberton D, et al.Phase 2 evaluation o parainfuenza type 3 cold passage mutant 45 liveattenuated vaccine in healthy children 6-18 months old. J Inect Dis2004;189:462-70. PMID:14745704doi:10.1086/381184Madhi55. SA, Petersen K, Madhi A, Khoosal M, Klugman KP. Increased diseaseburden and antibiotic resistance o bacteria causing severe community

acquired lower respiratory tract inections in human immunodeciency 27virus type 1-inected children. Clin Inect Dis2000;31:170-6. PMID:10913417doi:10.1086/313925Zar56. HJ, Hanslo D, Tannenbaum E, Klein M, Argent A, Eley B, et al. Aetiology andoutcome o pneumonia in human immunodeciency virus-inected childrenhospitalized in South Arica.Acta Paediatr2001;90:119-25. PMID:11236037doi:10.1080/080352501300049163Laxminarayan57. R, Mills AJ, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M,et al. Advancement o global health: key messages rom the Disease ControlPriorities Project. Lancet2006;367:1193-208. PMID:16616562doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68440-7Sinha58. A, Levine O, Knoll MD, Muhib F, Lieu TA. Cost-eectiveness opneumococcal conjugate vaccination in the prevention o child mortality: aninternational economic analysis. Lancet2007;369:389-96. PMID:17276779doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60195-0

Miller MA, McCann L. Policy analysis o the use o hepatitis B, Haemophilus59.infuenzae type b-, Streptococcus pneumoniae-conjugate and rotavirusvaccines in national immunization schedules. Health Econ2000;9:19-35.PMID:10694757doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(200001)9:13.0.CO;2-C

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12724479&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa022823http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16163262&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17456820&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.16.1784http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.16.1784http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11172176&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200102083440602http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17124755&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17698577&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2836http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16437500&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17259870&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000253053.01151.bdhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17137887&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.06.036http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11997303&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bmb/61.1.133http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10690253&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02724939992455http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=7746695&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15876939&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000160942.84169.14http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000160942.84169.14http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=8970219&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199612000-00008http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16107294&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.038http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15288824&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01106-5http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17006288&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000237830.33228.c3http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12075763&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-200204000-00011http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16517274&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68304-9http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68304-9http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10551490&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00232-9http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11010838&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1086/315859http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11996399&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10485741&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=14745704&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1086/381184http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10913417&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1086/313925http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11236037&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1080/080352501300049163http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16616562&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68440-7http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68440-7http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17276779&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60195-0http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10694757&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(200001)9%3A1%3C19%3A%3AAID-HEC487%3E3.0.CO%3B2-Chttp://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(200001)9%3A1%3C19%3A%3AAID-HEC487%3E3.0.CO%3B2-Chttp://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(200001)9%3A1%3C19%3A%3AAID-HEC487%3E3.0.CO%3B2-Chttp://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(200001)9%3A1%3C19%3A%3AAID-HEC487%3E3.0.CO%3B2-Chttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10694757&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60195-0http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17276779&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68440-7http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68440-7http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16616562&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1080/080352501300049163http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11236037&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1086/313925http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10913417&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1086/381184http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=14745704&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10485741&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11996399&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1086/315859http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11010838&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00232-9http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10551490&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68304-9http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68304-9http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16517274&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-200204000-00011http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12075763&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000237830.33228.c3http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17006288&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01106-5http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15288824&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.038http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16107294&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199612000-00008http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=8970219&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000160942.84169.14http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000160942.84169.14http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15876939&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=7746695&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02724939992455http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10690253&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bmb/61.1.133http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11997303&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.06.036http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17137887&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000253053.01151.bdhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17259870&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16437500&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2836http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17698577&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17124755&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200102083440602http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11172176&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.16.1784http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.16.1784http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17456820&dopt=Abstracthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16163262&dopt=Abstracthttp://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa022823http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12724479&dopt=Abstract