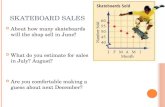

bonesbrigade.com · Web viewThey dominated contests, made hundreds of thousands of dollars, created...

Click here to load reader

Transcript of bonesbrigade.com · Web viewThey dominated contests, made hundreds of thousands of dollars, created...

NEED TO INCLUDE THESE ADS: SEX SELLS /TONY FACE PAINT/RAY BONES BURNING CAR/ MCGILL FLEXING WITH THOUGHT BUBBLE/ HAVE YOU SEEN HIM/ WHAT THEY'RE SAYING ABOUT OUR NEW 86 LINE/RAT BONES COLLAGE CIRCA 1984.NEED TO INCLUDE THE FOLLOWING IMAGES: HAWK SCREAMING CHICKEN SKULL/MCGILL'S SKULL AND SNAKE/LANCE'S FUTURE PRIMITIVE/ TOMMY'S FLAMING DAGGER/RODNEY'S CHESS/ STEVIE'S BEARING DRAGON

THE BONES BRIGADE: AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY

It's not a death metal band, an extreme diet club or historic dominoes association—the Bones Brigade was a talented gang of teenage outcasts. Unmotivated by fame or popularity, they completely dedicated their lives to a disrespected art form. For most of the 1980s, this misfit crew headed by a 1970s ex-skateboard champion blasted the industry with a mixture of art and raw talent becoming the most popular skateboarding team in history. The core unit of the Bones Brigade built an empire that covered the world. They dominated contests, made hundreds of thousands of dollars, created the modern skateboard video, reinvented endemic advertising, pushed skate progression into a new era, and set the stage for a totally new form of skating called street style. There's nothing comparable in today's skateboarding.

In 1978, a mechanical engineer who had developed new skateboard products teamed up with one of the most popular skaters of the era. George Powell and Stacy Peralta created Powell Peralta and immediately began retooling how skateboard products were made and marketed.

George, who had started developing products in his garage and kitchen oven, went on to invent innovative equipment such as double radial Bones wheels, named for their unique whiteness, and trend setting skateboard decks. Stacy recruited the skaters and handled marketing along with his longtime creative cohort Craig Stecyk III. Rejecting the expected action shot marketing, they used their young team to create esoteric images conveying the culture's sarcasm and disenfranchised dark humor. While spitballing about his stable of skaters, Stacy commented that he never wanted to call them a "team," a label that invited all kinds of jock baggage. Craig shrugged and simply said, "Bones Brigade." Powell Peralta reinterpreted a military motif, warping it with pioneering skateboard graphics more suited to biker gang tats than decks. As great a skater as Stacy was, his scouting skills surpassed any celebrated onboard skills. By 1984, Tony Hawk, Rodney Mullen, Steve Caballero, Lance Mountain, Tommy Guerrero and Mike McGill compiled the most competitively dominant skateboard team in history. On top of winning large, cheap plastic trophies, Tony Hawk and Rodney Mullen—two 13-year-olds initially ridiculed by their peers—created new ways to skate and pioneered modern technical skating.

Disgruntled at the way the skate mags played favorites, Stacy weaponized consumer VCRs by directing the Bones Brigade Video Show in 1983. The low-budget

amateur skateboard video was the first of its kind and sold a surprising 30,000 copies (including Betamax!).

At the time, skating needed all the help it could get. The 1970s "fad" that swept the country after the invention of the urethane wheel had deflated embarrassingly by 1981. Remaining participants' social status ranked below the chess club. Powell Peralta averaged an anemic 500 monthly board sales and Tony Hawk once received a royalty check for 85¢. To increase brand awareness and grow skateboarding, Stacy produced and created a new Bones Brigade video every year, showcasing his crew's varied personalities and invented maneuvers. The videos routinely featured riders crawling out of sewers, skating abandoned pools and back alleys, bombing desolate hills—essentially shredded an apocalyptic world hidden to most non-skaters.

By the mid-'80s, Brigade videos were sold all over the world and a new generation of teens discovered skating, making the Brigade international stars. The dearth of skateparks forced enthusiasts to DIY it, triggering a wooden ramp revolution. Endemic brands had started their own magazines and for the first time skaters controlled every aspect of skateboarding. Powell Peralta peaked in 1987 with $27 million in annual sales while its pro team continued to dominate contests, cash $20,000 monthly royalty checks, tour the world, occasionally cause riots and star in the ambitious The Search for Animal Chin, which remains the most successful skateboard video of all time.

But the activity's cyclical nature reaffirmed itself by the end of the decade and skateboarding descended back to the faded fad category. The industry broke apart as zeros dropped off checks and most top pros drifted away in search of second jobs. Powell Peralta dissolved over the owners' business differences and Stacy left to pursue filmmaking in Hollywood. Almost all the core Brigade members split and started their own skateboard brands just like their mentor had in 1978. George regrouped and continued making skate products under the Powell and Bones banner.

Twenty years on, the Brigade all remain in skateboarding. Although they've succeeded in separate endeavors, they continue to be bonded together as veterans of a culture war. Tony Hawk, Rodney Mullen, Lance Mountain and Steve Caballero remain skate stars while Tommy Guerrero runs a skate brand and Mike McGill owns and operates one of the most successful independent skate shops in the country. In 2001, Stacy returned to skateboarding with his award-winning documentary Dogtown and Z Boys.

TONY HAWK During the start of his reign as world champion skateboarder, a high school Tony Hawk was manhandled by jocks, spat on by skate legends and rode a sanitation ditch all the way home after matriculating. The 15-year-old pro had discovered his brother's discarded banana board only four years earlier, but his pathological determination allowed the scrawny skater to barge through obstacles unique to any pro skater. Tony outlasted and outshined his detractors, eventually winning them over with his creativity and willingness to sacrifice his body to progress skateboarding. From 1983—1999, Tony entered 103 professional skate contests, winning 73 of them and placing second in 19.

But, as the documentary points out, competitions are a mixed bag for skaters. Tony's real pleasure came from skating for himself and not a panel of judges. He spent most days during the 1980s altering skating's future at the cruddy local Del Mar skatepark or his private ramp. He developed a method of mid-air grabs allowing for greater technical precision and invented over 80 vertical maneuvers.

Along with changing how people skated transitions, Tony dismantled and rebuilt the possibilities for professional skaters. His career repeatedly rode through loserdom and fandom and he cashed chaotic monthly royalty checks ranging from 85¢ to $20,000. As the world's most recognizable skateboarder, he headed into uncharted territory attempting to fuse skate culture with mainstream companies. Tony's partnerships weren't always as successful as his contest runs, but the ones that worked cut a new path for other pros to follow.

Tony and the mainstream connected in an unprecedented way at the end of the millennium. By 1999 he'd already won a fistfuls of X Games medals but landing the first 900—arguably skateboarding's most sought-after trick—as ESPN zapped the contest all over the world changed mainstream perception. Skating broke into sports pages just as Tony's biography climbed the NYT bestseller list and the first installment of his video game series unexpectedly scaled the sales charts. (Eventually, the series raked in over a billion bucks in sales).

What does a world champion do to cash in on that string of successes? He retires from competition so he can skate how he wants to, learning whatever tricks spark his fancy. "I don't think my success has changed my outlook on skating," Tony says. "If anything, it gave me a chance to skate more the way I always wanted to."

Today Tony still skates as much as before and runs Birdhouse Projects, his skateboard company. As the most popular alternative athlete in the world, he continues to travel the world for demos, award shows, charity events and has transformed into a brand himself. Tony Hawk Incorporated fills a large office building with unusually high ceiling allowing for his custom built million-dollar ramp. He juggles photo shoots for Forbes and The Skateboard Mag and his peers still call him a skate rat regardless of the material rewards of his career. His foundation has donated over $3,000,000 to help build skateparks in low-income areas. Tony still shreds backyard pools, invents tricks and ices his hip when innovation doesn't go as planned.

RODNEY MULLEN "I struggle with isolation and skating to this day," Rodney Mullen says, but no other professional skateboarder has thrived in the woods like Rodney. Raised on a rural Floridian farm, the skate obsessed 11-year-old practiced every night with only his dog and wandering cows watching. On weekends, he'd beg his mom for a ride to Sensation Basin skatepark until it closed.

A major motivation behind the isolation was the incendiary anger of an abusive father whose hatred for skateboarding only intensified with every trophy his son dragged home. When Rodney returned from California, struggling with an oversized trophy that crowned the 13-year-old the youngest freestyle world champion, his father took him in before saying, “Good, now you can move onto something real” and made him promise to quit skateboarding.

Rodney finagled a hall pass to skate again, but the giveth and taketh pattern repeated over the years creating an unparalleled attachment between skater and his board. Stress squeezed out in unpredictable ways for the teenager fearful of losing his sole escape from the traumatic home atmosphere. While paving the best record in professional skateboarding—winning 32 of 33 professional freestyle contests over a decade—Rodney suffered from anorexic tendencies, often slept in his closet, went days without talking and battled depression while maintaining a 4.0 GPA.

The contest wins are mostly forgotten and Rodney disposed of his trophies long ago, but numerous tricks he invented on that rural farm remain as bold strikes on skateboarding's evolutionary timeline. Rodney looked outside of the flatland prison of freestyle skateboarding and invented ways to do tricks mid-air without ramps. By inventing the flatland ollie he opened up another plane for his skateboarding and quickly went berserk on his board, unleashing a flurry of tricks—kickflips, heelflips, 360 flips, impossibles. These tricks were so advanced that his freestyle peers were unable to learn them and it took a new generation of skaters to adapt them into building blocks for street skating. It wasn't until board technology advanced—and we were all allowed to cheat—that these tricks became accessible to the masses.

Alas, Rodney had picked the dodo of skate styles and for all intents and purposes, freestyle went extinct in 1990. By then he had quit Powell Peralta, literally escaped from his father's house under the cover of darkness and co-owned World Industries, the most popular skateboard brand at the time. Stubborn as a mentally ill billy goat, he simply stockpiled freestyle boards and skated alone as usual. Slowly, a close friend managed to convince him to try skating streets.

Rodney came to enjoy the challenge and years later added another level of technical proficiency to street skating. He and his partners sold World Industries in 1998, providing Rodney with enough money to "skate exactly as I wanted." Essentially, this means continuing to skate from midnight to 4 a.m. Alone.

Unlike traditional sports where jocks enjoy dominating competitions, Rodney loathed the entire process, seeing it as an exercise that hobbled progression. The most dominant freestyler competitor in the world has never entered a street contest. This didn't stop him from winning the Transworld Skater of the Year award in 2006. He gave away that trophy too.

STEVIE CABALLERO The smallest member of the Bones Brigade packed the most power. Mentor and coach Stacy Peralta once compared Cab's size-to-power ratio to that of a primate. The first recruit of the core unit of the Brigade initially didn't make such a strong impression on everyone. Stacy recruited Cab in 1978 after watching him underwhelm the judges at a contest who placed him fifth. But just like with the rest of the Brigade, Stacy recognized that Cab's power originated from a unique and explosive motivation, one that would be a game changer if detonated.

Cab was the first skater to blend the 1970s-era style emphasis with the upcoming power and technicality emphasis. "He was the innovator," Tony Hawk says. "He did switch inverts. Nobody did switch stuff back then." Cab's heat in the skate world was so unrivaled that it boosted Powell Peralta's reputation, defining it as the brand for the new

generation. In 1980, on his way to becoming a world champion, he invented his namesake Caballerial, a 360-degree no-handed aerial. This was no simple extension of another trick—Cab looked as if he'd returned from time travel with a futuristic trick and it dramatically altered how skaters thought of tricks.

Cab evoked fan-outs from everyday skaters as well as fellow Brigade mates. After joining the Brigade and desperate to make an impression, Tony Hawk infamously ate spent chewing gum from Cab's toes while soaking in a hot tub. (Tony was only 12-years-old so cut him a teeny bit of slack.)

The teenage Cab thrived through skating's early-'80s depression and submerged into skate culture more than any other professional. He squeezed a ramp into his narrow backyard and his house became the hub for the San Jose vert scene. His band The Faction helped usher in skate rock with the song "Skate and Destroy" and he spent hours publishing Skate Punk, a DIY Xerox zine to stoke the scene and act as a low-fi information portal since the major slick mags had ceased publication.

Along with the rest of the Brigade, he crowded the top five spots at contests during the 1980s and in 1988 used his power to blast a world-record backside air, boosting 11 feet above a ramp. Besides leading the way on his board, Cab was the first pro to define a new endorsement market. His signature Vans shoes revolutionized how pros made money and redefined when a skater arrived on the top shelf. Unlike his Brigade peers, the royalties from Vans allowed Cab to comfortably weather skating's last depression during the early-'90s.

Cab's signature shoe continues to thrive almost a quarter-century later, just like the skater who continues to blast out of pools and slide around tiles. Cab was the only Brigade member to stay with George when Powell Peralta disbanded. No other professional skater has stayed with a board sponsor longer. Maintaining friendships with George and Stacy, Cab played an integral part in repairing his mentors' relationship and helping resurrect the Powell Peralta brand.

LANCE MOUNTAIN Unlike Tony Hawk, Rodney Mullen and Stevie Caballero, Lance Mountain's skateboarding wasn't motivated by technical progression. Hooked on the rolling carefree freedom as a kid, Lance simply didn't want that feeling to end. "The point of skateboarding was to stay young and have fun," Lance says. "It was never, in my mind, this thing to do to get in the Olympics or be famous or win first place. Skateboarding totally stunts you. It keeps you immature. There was a fear of growing up. Still is."

Lance built his own playground in his backyard, constructing one of the earliest ramps with extended flatbottom. The Mountain Manor Ramp became an international destination and Lance often returned home to find a crew of unknown skaters babbling in a foreign language on his ramp. His love of skating pushed Lance to progress in whatever direction felt fun and he caught the attention of Variflex skateboards. During the 1980s, contests defined a pro's worth, but early on Lance proved incapable of taking them seriously and often placed last by dorking around mid-run.

Variflex turned Lance pro just as skating dropped into a depression. Cashing $14 royalty checks wasn't a problem while Lance lived at home, but around the time he graduated, Variflex quit making pro models and essentially became a toy company.

Lance's pro career was dead and he worked a variety of jobs while paying his own way to contests to skate with friends.

The skateboard world was tight during the early '80s and Lance's mom asked Stacy Peralta—as an ex-pro who remained in skateboarding—for advice. Stacy hired Lance as an intern of sorts: a quasi pro that would train to take over as Bones Brigade team manager. While the other Brigade members focused on pushing skateboarding boundaries, Lance's skating naturally expressed his fun-loving personality. "I always knew when I got on Powell exactly what I represented," Lance says. "I knew that most skaters weren't as talented as the Powell team, most of them are like me. I was a real skateboarder, not a gifted skateboarder."

Lance was told not to expect a pro model from Powell Peralta, but realized he could force the issue if he exchanged his worth into currency everybody used. "I had to make a sacrifice and some of the fun and carefree attitude kind of went out the door," he says. "I had to win contests and make a little money and prove myself and that was work." The self-described "not a gifted" skater beat the most elite pros on numerous occasions and the winning results did indeed increase his perceived worth. But it was Lance's personality that ultimately earned him a Powell Peralta pro model and turned him into a star. Stacy's first skateboard video provided a new medium that perfectly projected Lance's love of fun and The Bones Brigade Video Show instantly created a fervent fanbase.

Lance's personality burned through his contest accomplishments and he became the most beloved member of the Brigade by personifying the love of skateboarding rather than the progression. Most skaters couldn't directly relate to the technical mastery of Tony and Rodney and lacked the power of Caballero, but Lance seemed to say that it's all right as long as you love skating.

Today, Lance continues his professional career, skating for some of the most popular brands in skateboarding. His name has become shorthand for the goofy, fun-loving aspect of skating and he's still featured on the cover of skateboard magazines, travels the world skating demos and just last year was nominated for best transition skater by Transworld Skateboarding magazine. He has two pools in his backyard—one for soaking and an empty one for shredding.

TOMMY GUERRERO For a poor city kid in 1975 San Francisco, the rollercoaster hills directly outside the front door made skateboards a particularly thrilling toy. Tommy Guerrero began rolling around the hills on a hand-me-down prehistoric board with clay wheels, which was a Cadillac compared to his buddies. "A friend made a skateboard out of an old Formica table and put rollerskate wheels on it," Tommy remembers.

Tommy eventually progressed to modern equipment and by age 10 was bombing the local hills, weaving through traffic and dodging angry residents armed with garden hoses to spray the rambunctious kids who treated the bus up the infamous 9th street hill like a ski lift. He also hit the local skateparks and caught the attention of a sponsor for his inherent flowing style. Still a kid, Tommy peaked on the concrete waves just as skateboarding slumped into a massive depression in 1980. Participants moved on and virtually every skatepark in the country closed.

Feeling betrayed, Tommy cut up all his membership cards and seethed until he slowly transformed his urban surroundings into a giant skatepark. Reinterpreting everyday obstacles like ledges and curbs, Tommy skated in a manner that was uncategorizable during a time when only vertical and freestyle were recognized as legitimate styles of skateboarding.

Viewed as a lark by most professionals, San Francisco hosted the world's first "street style" contest in 1983 and even actual street skaters didn't fully understand the concept. Tommy, unfamiliar with the label and contest rules, entered against the world's best pros and cleaned up. The organizers handed Tommy a trophy sans prize money due to his amateur status and things flashed from sweet to sour. "I was pissed," Tommy says. "'What the fuck? Where's my loot? Give me the loot!'"

Powell Peralta turned Tommy pro two years later and his groundbreaking segment opened Future Primitive, the most anticipated skateboard video of the year. It was the first time any video singled out and showcased street skating. At age 19, Tommy opened his first bank account and began dumping in tens of thousands in royalties. Tommy and a handful of other street pros introduced what would become the most popular form of skateboarding. By implementing their own creativity and some of Rodney Mullen's tricks, they showed starting skaters as well as elite pros the potential in everyday streets. "Watching Tommy's part in Future Primitive and he ollies over the bushes—that was it," Tony Hawk says. "I thought, You can ollie over obstacles—you don’t need a ramp!"

Tommy was infused with a natural style on and off his board, speaking, dressing and skating differently than his fellow suburban established pros. Unlike vert skating with the hassles of available terrain and cumbersome padding up, average kids immediately connected with Tommy who simply opened his front door and started tearing it up.

Tommy is remembered as one of the premiere stylists of the streets, a trait that never ages out regardless of generational trends. After leaving the Brigade, Tommy started REAL skateboards with his friend Jim Thiebaud and it remains one of the world's most popular skate brands. A musician since his teenage years—his first band's name "Free Beer" guaranteed a crowd—Tommy established himself as a world-renowned guitarist. Besides touring the globe for gigs, he provided some of the soundtrack for Bones Brigade: An autobiography. MIKE MCGILL No skater has ever carved out such a brutal demarcation line as Mike McGill did with his McTwist. When he unveiled his mid-air, flipping 540-degree spin at a 1984 contest, he literally broke professional careers on the spot. A large portion of the professional vert world never recovered. The skaters who learned the trick spent months struggling with self-doubt and unaccustomed long-term frustration that reduced many to tears. "I remember landing it and walking over to the brick wall and smashing my board into pieces," Lance Mountain remembers. "I wasn't even happy that I made it … I was pissed it had to be that much a battle."

Raised in the stifling atmosphere of Florida, Mike tagged along with a friend on a 1979 trip to Stacy Peralta's house. Stacy gave the young teenager an old board and Mike

skated with him during a photo shoot. The tagalong scored the centerfold photo in SkateBoarder and soon began receiving brand new gear from Stacy. Mike and Stevie Caballero represented the foundation for the core unit of the Bones Brigade. A hard worker without the natural talent of a Caballero, Mike's drive and dedication overcame any genetic disadvantage. Powell Peralta turned him pro and the royalties dramatically increased with his second round of graphics. Mike's signature below a skull clenching its teeth around a twisting snake is a board that continues to sell today.

Mike consistently placed in the top five during early 1980s contests and predictably hummed along until pushing himself to make the McTwist. "It took a lot of courage because I didn't necessarily do that kind of thing," Mike says. "I didn't take that kind of risk."

Rodney Mullen's initial reaction upon witnessing the McTwist was a thankfulness for not skating vert and that is was "neck breaking material." Lance, the first vert skater to watch Mike stomp the trick, stood stunned and thought, "What the heck just happened?" One of the major skate magazines put Mike on the cover with two simple words: The Trick.

Mike was more than just a pro with a kickass trick. He involved himself in the core scene by opening McGill's Skate Shop in 1987. He also operated a skatepark—always a losing proposition—to provide a destination and safe haven for local skaters. While other vert skaters were left destitute when skating dropped in the 1990s, Mike simply downsized his career and focused on supporting skating through his shop.

Today, people continue to struggle with McTwists and amazingly, unlike other groundbreaking trick, it remains a demarcation line for skating.

George Powell The first time George Powell saw a skateboard it wasn't called a skateboard. "I saw somebody riding a two-by-four near the beach and went home and built one for myself," George says. In the mid-1950s there were no commercially available skateboards but the OG generation lit the fuse with DIY projects involving scrap lumber and mutilated rollerskates.

A decade later, George was married and studying engineering at Stanford. He hadn't rolled in years, but cashed in his books of blue chip stamps for two commercially produced skateboards. He and his wife eventually burned out on rolling around the campus and mothballed the boards.

A decade after that, George passed down his skateboard to his son, who promptly complained that his relic ride sucked compared to newer models with urethane wheels. Ever the tinkering scientist, George researched the new material and composite decks and set up a low-rent R&D lab in his garage and began baking prototype wheels in his kitchen oven. His day job revolved around the aerospace industry and he employed its high-tech approach to making aluminum skinned decks and the first double-radial wheels called "Bones" due to their rare white color.

George ran Powell Skateboards with moderate success until one of the most famous skaters of the era randomly rang him up in 1978. Stacy Peralta and George had spoken a few times before and the skater had always been impressed with Powell's

product. The engineer likewise appreciated the marketing power that the star skater provided. "I was a designer—I didn't know many skaters," George says. They formed Powell Peralta and each owned their own side of the company coin. Stacy and his creative cohort Craig Stecyk tackled marketing, quickly producing artistic and sardonic ads unlike anything seen in skateboarding. George hunkered down and focused on improving skate product. Powell Peralta found their stride at exactly the wrong moment. "Stacy had just introduced the Bones Brigade concept," George says, "we had really high-quality wheels and decks and then the market just died. Went to zero. We'd call shops for orders and they'd say they were going out of business."

Powell Peralta weathered the depression until a new generation discovered skateboarding in the mid-'80s. Sales peaked in 1987 with annual sales topping 27 million bucks, but by the end of the decade the landscape had changed and the iconic company absorbed multiple near-fatal wounds. Stacy and most of the Bones Brigade departed, but George retooled his business and brought his companies back from bankruptcy by returning to his original focus on upgrading standard skateboard components. Today, Bones Bearings and Bones wheels are among the strongest and most respected brands in skateboarding.

STACY PERALTA In 1977, Stacy Peralta was a 20-year-old champion skateboarder with the world's best-selling skateboard model. Renowned as the smoothest pro around, he starred in movies and travelled the world as an ambassador for skateboarding. Unfortunately, accomplishments like this mutated hideously when transferring outside the skateboard bubble and an adult dedicating himself to a kiddie fad made him snicker bait for non-skating peers.

"Skateboarding was considered as trivial as the pogo-stick," Stacy says. "I sometimes think how remarkable my parents were because if my son spent the greater part of his day riding a pogo-stick, I’d worry about him."

The fact that Stacy cashed monthly checks in excess of five Gs may have shifted his parent's perspective, but he soon put a stop to that. A typical 1970's-era professional skater career mimicked fireworks: blast up, blow up and fall down sputtering out. Naturally, most pros rode that ride as long as possible, but Stacy quit Gordon & Smith skateboards at his peak and partnered up with engineer George Powell to start their own brand Powell Peralta in 1978. No other pro had pulled the e-brake on his own career and it confused fans to no end. Not wanting to overshadow the young team he recruited, Stacy refused to issue himself a pro model on Powell Peralta but still won SkateBoarder magazine's skater of the year in 1979. Officially retired, Stacy surprised himself by enjoying nurturing his team even more than his own pro career.

And he kicked ass at it. Stacy had an unparalleled instinct for finding hidden talent, always bypassing obvious choices to recruit raw and "weird" skaters based on personality rather than obvious physical talent. Steve Caballero was picked after placing fifth in a contest. After bailing a trick, Tony Hawk's face full of self-disgust caught Stacy's attention. He recognized Rodney Mullen's technical precision stemmed from a desire to control something in his emotional harrowing life.

By 1983, Stacy had picked a team that dominated contests and created entirely new ways of skating. Unhappy with the way the magazines covered the Brigade, Stacy and cohort Craig Stecyk III circumvented them with newfangled VCRs and created a new propaganda weapon. After firing the non-skater he'd hired to direct, Stacy gave himself on-the-job training and created what was essentially a Powell Peralta's low-fi home movie. The Bones Brigade Video Show was the first skateboard video and it instantly rearranged skate media priorities. Expecting soft sales of perhaps 300, they sold a hundred times that and boosted Powell Peralta's market share in the process. Future Primitive: Bones Brigade Video 2, released in 1985, is often argued as the "best" skateboard video ever produced. Unlike BBVS's simple linear storyline and collection of tricks, Primitive marinated itself in skating subculture. Skaters crawl out of sewers, skate back alleys and decrepit ditches. Primitive pointedly turned away from the mainstream. Gone were the days of longing to be accepted and the Brigade reveled in skating's anointed position as cockroaches of traditional sports as they skated an apocalyptic landscape.

Stacy directed a steady string of successful videos, peaking in 1987 with the beloved cheese fest The Search for Animal Chin, an ambitious story of the Brigade's search for the elusive Chin. (Think 1970s-era porno with skating instead of sex. The acting quality was pretty much the same though.) Skating bombed out three years later and Powell Peralta crashed and burned. Stacy had held together skateboarding's most successful team for a decade—dog years in skateboard terms. The team's influence regarding contest domination, progressive tricks, marketing has never been matched. After leaving Powell Peralta, Stacy pursued his filmmaking aspirations, eventually writing feature film screenplays and becoming an award-winning director.

TONY HAWK INTERVIEW

QUESTION: What were you thoughts upon hearing that the BONES BRIGADE: AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY was going to be made?TONY HAWK: I was excited. I knew it was going to happen eventually, but I was more relieved that Stacy [Peralta] was directing it because anyone else's version wouldn't be from an inside perspective. I know Stacy is one of the best documentarians and when you combine that with the fact that he was there the whole time, it's obvious that he was the best choice. What was your reaction after seeing the first screening?TH: I was surprised at how emotional it was. It seemed like it was going to be more of a celebration of our time, not anything so deeply emotional and personal. I had a sense of it during the interview, but I had no idea how deep everyone else would go. I thought I exposed as much as I could and felt vulnerable because of it, but then I saw the other guys and realized that I didn't even get started. After seeing it, I think we all feel a bit more vulnerable and exposed as to what the days of the Bones Brigade meant to us. I think Stacy is the only one who would have gotten it out of us. We just didn't trust anyone with our story.Many TV shows have produced segments about your life—how does this film differ from them?

TH: This film is more about the psychology of what we did and why we even started trying to do it while those other TV shows highlights the accomplishments. This time we're really talking about what drew us into doing something so different.What did you think of the segment on the magazine manufactured rivalry between you and Christian Hosoi?TH: I was happy to explain it after having lived through it. I wasn't emotionally tied to it so it was pretty easy. I liked how it put it in a new light because a lot of people misperceived it as Christian and I being enemies. We weren't enemies—we were the top competitors who, by default, were pitted against each other in the eyes of the public. In reality, we were just having a blast being young and successful.During the 1980s, that success rarely transcended the skateboard bubble. In the film, there's a clip from an Italian TV show featuring you and Lance. Can you lay out the backstory to give people a sense of how you were regarded by the mainstream back then?TH: We were brought to Italy to perform on a TV show and were basically considered strange circus freaks. There was a Roller Boogie crew, a guy that juggled chainsaws, the hacky sack champions and us, as skaters. They built a ramp on stage and we explained that the ramp wasn't solid enough. Through various language barriers they told us that we'd never break this ramp. On one of my first runs, I knee slid and my knee went through the ramp. Then they tried to dress us in what amounted to painted cellophane shorts. During our practice session, my board shot off the ramp into the audience seats. They thought it was too dangerous so they taped our segment and showed it to the audience during the show. Lance and I then snuck into the audience so we were spectators to our own "demo."The Brigade went through a lot of strange times together, did that create a unique bond between you guys? TH: Absolutely. We have a strong connection that we'll always have because we did go through so much at a young age and within a short time frame. We knew we were part of something special at the time, but I don’t think we realized the resonance it would have and how formative it would be for people of the same age or interest levels. We were happy to be liked, but didn't recognize that we were inspiring people to follow their dreams. Some people saw us as examples of doing what you love despite the status quo. Many skaters have a limited sense of the history. Do you think this film shows cultural aspects that are difficult to convey to younger skaters?TH: I think it'll help enlighten kids nowadays as to what their roots are. Some of them make a lot of false assumptions about how we started skating and how we became successful. They just assume that it was always the way that it is now and you always had the opportunity to be successful and make a career out of skateboarding. None of that existed. I think we helped create that.Has this documentary experience brought you guys closer?TH: It's definitely been a catalyst for us to start working together again because we want to help promote the film, but also assess each other's interest levels in

doing reissues and how far we want to take this nostalgia. It's definitely made us question if we want to live in this nostalgia or be known for who we are now and that's a fine line to walk. It's been an ongoing conversation with all of us. The bottom line is that we want to approach this as a group with a common goal.Unfortunately, the group will be minus you in Sundance. TH: When Stacy told me the screening dates I was disappointed because I'd already committed to a tour in Australia. Had I known about Sundance earlier, I would have made it work, but it was too late: I was contractually locked in. I have a few days off during the tour and did try to figure out how to fly back for one of the screening, but it's physically impossible. Even though you’re spectacularly successful, do you still feel like that scrawny skate rat kid obsessed with something dismissed by most people?TH: I don't think my success has changed my outlook on skating. If anything, it gave me a chance to skate more the way I always wanted to. For a long time, I didn't want to compete and I wanted to be more flexible in terms of my opportunities. During the '80s, if you weren't competing as a professional skateboarder, you couldn't make a living. That was the bottom line. But once it hit in this bigger way, I was able to create a new path for myself where I could still skate actively, be progressive and be recognized without competing. If anything, this success has allowed me to pursue my dreams on my own terms. You pioneered new opportunities for professional skaters–are you still expanding those boundaries?TH: Yeah. I'm still making it up as I go along. In a lot of ways, I'm one of the guinea pigs of how far can you take this and at what age do you cease being effective or progressive. I'm still trying tricks. I've spent the last two days trying to get a new trick on video and I'm going to go out next week and do the same exact thing until I get it.

LANCE MOUNTAIN INTERVIEW

QUESTION: Do you recall the initial conversation you had with Stacy about doing a Bones Brigade documentary?LANCE MOUNTAIN: When the Dogtown and Z Boys documentary came out, I remember asking Stacy, "What next? Are people asking you to do the next one about The Bones Brigade?" He said people were already mentioning it to him and he was like, "No way! I'm not doing that." That was around ten years ago.

A lot of people were asking me when were they going to do a documentary on the 1980s, the era when I became popular. I understood why: The numbers of us who grew up idolizing Alva in the 1970s was in the hundreds of thousands but it was in the millions for the 1980s, so a lot more people were asking me about doing a film on the Bones Brigade. Q: You played a catalyst in getting the film rolling, right?LM: I just felt that it would be good and what people wanted. The main guys in the Brigade have moved on and had great lives after the Powell Peralta broke

up, but there was something about that time that was special to skateboarding. We didn't need to revisit it. Skateboarding has only grown better for all of us involved.

Skateboarding has missed a bit of what made the Bones Brigade special and that was all the necessary pieces being together and there's something to celebrate in that. I'm not sure that can be done again. Skateboarding has developed so much that it's probably not possible, so I think that story is good for skateboarding as a whole.Q: Skateboarding has so many nuances and unwritten codes. Do you think anybody who wasn’t there could tell that story?LM: No. Naw, naw, naw—it's our story. Not to bash anything, but it's like the difference between the documentary on Dogtown and the movie about Dogtown. They thought that real story wasn't interesting enough so they made some changes, made certain parts more accessible to non-skaters.

It's all about telling a story and who does that best and who has the best, most complete package to tell that story. It was the same back in the 1980s. This film doesn't say that other people or companies weren't contributing or doing innovative things but they didn't tell the story as well as Powell Peralta. Other teams and skaters were great, but their package or their storytellers were not as talented. The Bones Brigade had the best package for telling the story of that era. Stacy and Stecyk were the storytellers—they explained the story to skaters in the 1980s so why wouldn't you choose Stacy to tell the story now? He knows how to tell the story about skateboarding. Why would you go outside of that?

Skateboarding has always been a do-it-yourself activity or art form. You might be able to bring a documentarian who'll make a technically better documentary, but they won’t capture the spirit or the feeling of what skateboarding about. They'll just be documenting the facts and skateboarding has nothing to do with facts. It has to do with emotion and feeling and art and passion … it's just not facts. Skateboarding has never only been about being good only—it's about capturing someone's passion, making them love it. Skateboarding is theater. Nobody can document skateboarding better than a skateboarder.Q: Was it important for you to have this film made?LM: Yeah, because in some sense the chapter was never finished. It ended lame. It ended wrong. It ended sad. It didn't need to end that way. But, if it hadn't ended, each of us would never have gotten to the places where we are now. This film is important for skateboarding because history can change what's going on now. Skateboarding history hasn't always been available because the coverage, the articles written, were being done to market a brand. Whatever had happened was being covered up and written over to try and sell a product for tomorrow. For the longest time, skateboarding wasn't based on what had happened, it was about what was going to happen. One of the reasons that this movie could even happen is because Tony Hawk, Rodney Mullen, Steve Caballero and myself were the first skaters ever to have product on the market from the beginning of the '80s and we never left. Every other pro has had product for five years, ten years, dropped off, maybe come back decades later. This film

isn't just a look back on the glory days—we're still doing it. Now that a modern pro has a longer career, they're looking to us to figure out how to keep a career going for a long time. It's much harder for a kid starting out on a skateboard today to have a goal to do something creative, innovative, progressive—or just for fun their own way because circumstances and culture teach them the goal is to be famous.

This film shows that for anything to be of a certain value, have impact over time, it takes people being very passionate and working together combining different sets of skills. Not one of the participants on their own can overshadow the others and take whole credit for this being a thing of value. That's the story: teamwork and perseverance. It's just inspiring to skaters and non-skaters alike.

INTERVIEW WITH DIRECTOR STACY PERALTA

QUESTION: What was the most unexpected aspect of directing this film?STACY PERALTA: How emotional it made me. Being the person asking the questions, i.e. the interviewer, got me very involved with each of the characters while shooting and all of them brought so much material to the project that it really knocked me out. Lance [Mountain] broke down in his interview, which made me break down. And Rodney [Mullen] was so emotional during his entire interview … I hadn't expected that and it had a profound effect on me. During the 1980s, the guys and I shared moments of high elation and triumph together. Whenever I said good-bye to them at the airport, it was always sort of emotional because we were coming from such a rich experience, but I'd never had anything like this where it was so condensed and concentrated in such a short period of time. The interviews were conducted during one week, about six people per day, which is a very heavy schedule.You started with different expectations about what kind of film you were making?SP: Yeah, I had low expectations. Seriously. I was going to cut this film myself. I was looking to work on a little film that I could do on my own time. It wasn't until we began shooting that I realized we had something very unique and I could not make the film alone. I needed to bring in somebody who knows how to tell stories. That's why I brought in the editor Josh Altman. I really needed a partner on this film. He was the perfect person because he has a terrific sense of storytelling and a great understanding of how to connect the emotion of the story. I was too close to the material and quite a few times during post-production I told Josh, "I don’t really know what to do with this part of the film—you have to take over here. I’m just too close to it." I had so much trust in Josh. He had such a good feel for the material and characters.

What were the origins of this doc? How far back had you been planning it? SP: Around 2002 or 2003, Hawk, Cab, McGill, Lance and Tommy asked me to dinner at the LAX airport. They wanted to meet with me to talk about the possibility of a “Bones Brigade” documentary and if I would consider directing it. At that time, I was coming off of the success of Dogtown and Z Boys and didn't feel right about jumping into this field again, especially with a film where I was once again a character within the story. I felt it was too risky—way too risky. I was afraid of being looked upon as a narcissistic filmmaker. This is not to say that I didn’t feel the Bones Brigade was a viable history and potential good story. Over the years, one of the guys would reach out to remind me of it, but nothing happened until late last year when Lance called again and said something that tipped me over: “We're now older than you and Alva were when you made Dogtown.” That line made me realize now was the time. I talked to my wife at great length about the project. She knew my fears and reservations about the project and came up with the idea of calling the film "an autobiography." She figured that if anyone had any issues with me as the filmmaker or the guys making their own film in a sense, then telling them upfront should set it straight. The film is a collective autobiography. It's us telling our own story and we state that under the title of the film.From a purely physical perspective, how did the documentary evolve? SP: First thing I did was put the music soundtrack together. I do this with most of my films. I need to hear what the film sounds like, what it feels like and its emotional tenor. Once I assembled a couple of hundred pieces of music, I then began reaching out to photographers, asking them to send me their images from that era. I went through the Powell Peralta archives, which represents thousands of photos, and I looked through all the skate videos I made, including hours and hours of outtakes. I was in shock going through the old footage, especially with what Rodney and Tony were doing in the early '80s. Even though I filmed this footage myself and was there to see these tricks being introduced, it was like seeing them for the first time. They were so ahead of their time. They were laying down the tracks for future generations. And it wasn't just one or two innovations—they invented books of maneuvers. Rodney is like Chopin where he invented the studies. Both Tony and Rodney invented an entirely new vocabulary of maneuvers in skateboarding.

I put together questions as I sorted through the photos and videos. Hundreds of questions. I wrote questions for around 45 different individuals. I had to have totally different questions for Lance Mountain than I had for Tony Hawk and totally different questions for Duane Peters than I had for Craig Stecyk. It took me months to assemble these questions per each individual, subject, year, etc. It's the questions that generate the answers, which generate the narrative of the film.Did you structure the film beforehand and paint clear bulls-eyes on certain subjects?SP: As I put together the questions for each guy on the Brigade, I searched for the problems each of them may have faced during that time we were all together.

What emerged was that Rodney's father was a huge obstacle physically, psychologically and emotionally for him. Tony had an issue being accepted by people—he was spat on by skate punks back in the day and called a circus skater and many people in the skate world had issues with his father. Lance expressed huge insecurities about measuring up to the other guys on the Brigade and his interview ended up being rich with great material. On the other hand, Caballero didn't have that many issues and I struggled with him to find some. He kept saying that he went with the flow of his career and didn't fight it. He didn't have a lot of drama in his career, same with McGill. Did you realize early on that you'd have to convey the evolution of skating's disenfranchised culture for everything to make sense? SP: That's why we tried to show that skating went out of business in the early '80s. SkateBoarder magazine died. The sport died. Arena contests died. Skateparks died. The kids who wanted to keep doing it had to build backyard ramps and we decided to take skateboarding in our own hands and have professional contests in kids' backyards. At the time, none of us knew if skateboarding would ever come back or if it was gone forever. You and the core members of the Brigade shared a bond unlike any other in skateboarding. You were their boss, mentor and something of a father figure. How did that position affect how you made the movie? SP: It gave me an insight into the story. I knew the inner workings. I was there when Tony got spat on. I was there when Rodney suffered from what his father did to him. I was there when the tricks were introduced. It was a very unusual tightrope for me as a filmmaker and participant. Again, this was the reason I needed a skilled editor like Josh. He was very helpful in giving me the confidence to tell this story.Did you hesitate talking to the guys about painful issues?SP: Not really. The one thing that really moves me is that we can do a project like this and interact as if no time has passed. My relationship with these guys is so different from the Dogtown guys where a lot of ego was involved. A handful of the Dogtown guys didn't get what they wanted out of their skate careers, but everyone in the Brigade got what they wanted. They got broken up and took the bruises, but kept going until they got what they wanted. As a result there were no scores to settle or festering issues with one another to resolve. When it was over, we all walked away as friends, realizing what an amazing experience we had together.Did you schedule the interviews in a certain order or just let the skaters dictate when they were available?SP: I purposely scheduled the secondary interviewees towards the end of the week and the primary characters up front. I had Sean Mortimer come in first because I knew he'd give the general overview of the Bones Brigade experience. I started with Sean so that my crew could understand the film we were making. Sean was the first person on the first day and Rodney was the last person on that day because I knew Rodney had the potential to blow the crew away with his emotional, psychology and articulation of his experience. It's very important to me that my crew understand the film we're making, that they get

onboard and spiritually bond with it. I don’t mean spiritual in a religious way, I mean that they connect with it and that's exactly what happened by properly sequencing the interviewees.

At the end of the first day, the crew was absolutely stunned by what they'd heard. I really wanted them to think, I can't wait to come to work tomorrow. When that happens, the crew comes to work excited and creates a vibe that is tangible to people walking onto the set. The interviewees come in and feel that something special is going on. It makes a difference. Duane Peters came in and knocked his interview out of the park. Glen Friedman was amazing—everybody in the film gave amazing interviews. There was an actress working on the film as a digitizer and she wrote a letter to a friend in England saying how much they both had to change their lives after hearing these skateboarders talk about the artistic process.Even though there's lots of serious subject matter, the film is peppered with self-deprecation and the guys busting each other's balls. "Freak" is used as a compliment. And you really stick it in and break it off with your dorky early footage.SP: One thing I learned from Dogtown was that I didn't want this to be us patting ourselves on the back. I was hyper aware of that. But, if you look back, the Bones Brigade was hands down the most successful skateboard team of all time and so how do we say that … without saying it, you know? I felt there was potentially funny material from my career in the '70s and when I saw that goofy footage, I let Josh run with it. Josh understood how to take that material and cut it into the film in a way that makes those shots contextual but also funny. Glen Friedman and I were talking on the phone, months before production began, and he began ripping apart The Search for Animal Chin. He just tore it to shreds and made me laugh hysterically. We flew him out and got that on film. At the first screening, when the Chin segment came on, I could hear Rodney and Tony almost throwing up from laughing so hard. That was gratifying. There is a certain comic ownership to burning oneself. It's important to have that tonal mixture. When you have the guys tell the story about Rodney running out of the van, well, it shows that Rodney is a really unique, special guy and he's imperfect in that regard. He's extremely eccentric and he has needs. It was very, very important for me to give this film a personality that didn't resemble Dogtown in any way, either visually, physically or emotionally.Visually, it doesn't look anything like Dogtown. Most of the skating footage was shot on videotape and you emphasize that medium's inherent defects rather than treating them as problems. Josh did an amazing job with the titles, which even have that degraded tracking line going through them.SP: Josh and I worked really hard on the graphics and titles and I think it fits with that ugly '80s video look.After the first screenings, Tony Hawk commented a few times on how unexpectedly personal the film was for him.

SP: Look what Tony overcame during his early career! That says more about his character than anything else. He overcame so much adversity and that's what makes a good story. How has the experience been with the Brigade after the film? Do you think it rekindled anything within them?SP: They feel that as a unit, they had an experience in skateboarding that nobody else had during that decade. They've all told me that at different times. But, and this is very important, they did it at a time when skateboarding wasn't accepted by the mainstream. They clearly weren't doing it for the money because in the early '80s there wasn't any money to be made in skateboarding so there was a purity of intent to it. Like Lance said, their bond is similar to guys who experienced war together because at a very young age they shared one of the most meaningful and impactful experiences of their lives. Now we have it on a piece of film that we can share. Sundance seems almost like a tour redux for the Brigade. They used to travel the world together, stuffing themselves into budget vans and cheap hotel rooms. This time it's going to be full skate camp at a rented house with everybody crammed together. SP: It's going to be just like that! I only wish Tony could be there … he tried to find a way back from Australia but it wasn't feasible. He was actually trying to schedule flying in from Australia, attending a screening and then flying back. Tony called it "a global mission" in an email, but he couldn't make it work.There are around 20 million skaters worldwide and many of the Brigade remain stars. How do you think skaters will react to the film?SP: I would hope that the things these six individuals say in the film are things that other skaters and athletes and artists feel but perhaps have not been able to articulate. Non-skaters who have seen the film tell me they relate to it for the same reasons. At early screenings, I had people tell me the film isn't about skateboarding—it's about family. It's about the artistic process. It's about overcoming obstacles. Everybody is taking something different from it. The goal has always been to make the film universal and transcend the skateboard audience.Last question and this concerns the skateboarders who shredded during the '80s—will they ever be able to look at The Search for Animal Chin [The most successful skateboard video in history, released by Powell Peralta in 1987] the same way again?SP: Ha! My wife says that I've ruined it for so many middle-aged skaters and that they'll never look at Animal Chin the same way again. But another person told me that they'll actually appreciate Chin even more. I really don’t know.

RANDOM QUOTES FROM BONES BRIGADE: AN AUTOBIOGRAPHYGlen Friedman: "You couldn't find a nicer group of fucking Boy Scouts than the Bones Brigade."Stacy Peralta: "They weren't just guys who dominated competition, but they were also skateboarders who invented some of the most revolutionary maneuvers out of that entire decade."

Duane Peters: "I didn't like his [Hawk's] style. He was just an annoying little fucking kid with way too many pads on."Stacy Peralta: "Stecyk and I are spitballing ideas one day and I'm telling him that I don’t want to call this a team and I don’t want the word skateboarding in the name of it. Craig looks at me and says, 'Bones Brigade.'"Sean Mortimer: "Everybody is like: Who is this weirdo? He pops out, says some fortune cookie thing that makes no sense and then recedes back."Craig Stecyk III: "I would love to be able to tell you I'm wearing woman's underwear and I don’t know why I'm wearing woman's underwear, but I'm not."Lance Mountain: "They asked Cab, 'Could you hold this dead dog for an ad?' He said, 'Aw, I don’t want to do it.' I said, 'I'll do it!' I was Mikey that got all the cool stuff that they thought was lame."Steve Caballero: "It was the first time that I've ever had someone so serious and say, 'What's wrong with you? Don't you care about skateboarding?' I think I almost started crying."Rodney Mullen: "What makes us all do what we do at a high level is an inspiration that comes from so deep … almost a controlled desperation and if you can't tap into that then it extinguishes."Duane Peters: "I won two of the Whittiers and then I needed beer money. I didn't think I could win because I wasn't skating that much, but I knew I could get in the top 5. That was when I really noticed that Hawk was doing some shit that didn't make any sense to me."Tony Hawk: "The prize money for first at a pro contest was $150, but I was fourteen-years-old! Sign me up. I'm cashing in. I'm going to buy a Moped!"Stacy Peralta: "I learned early on from my own generation that one of the worst things you can do to a teenager is give them too much attention and money. It destroys their perception of themselves and it wrecks them." Tommy Guerrero: "We were in a van once and frightened … these kids are going to kill us! They were [screaming] 'We love you!" We were like, 'Wait a second! Let us get out of the van before you tip it over and light it on fire!'"Lance Mountain: "It sounds terrible to say, but our group of dudes pioneered the way to make money at skateboarding."Rodney Mullen: "He won everything, or close to it. That creates so much more pressure because there's no gratification in winning, there's only upholding something so you don’t lose it … it's like a Kafka short story: you build something but you can't live in the house because you sit around guarding it."Tommy Guerrero: "Rodney was fucking crazy. Completely. But in the mad genius way: He could tell you some historical fact, but then he'd be … 'Hey, how do you open this door?'"Lance Mountain: "Skateboarding has nothing to do with competition or sport. It has to do with trying to stay as immature as you can for the rest of your life. It's kind of a lame thing to say, but it really is."Craig Stecyk III: "Was there ever a skatepark designed that was as good as an average sewer or curb? No."