prairiegroupuu.orgprairiegroupuu.org/images/Scheilermacher._Neely._Paper.docx · Web...

Transcript of prairiegroupuu.orgprairiegroupuu.org/images/Scheilermacher._Neely._Paper.docx · Web...

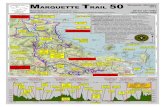

Schleiermacher’s Transient and Permanent A paper for Prairie Group 2014Pere Marquette State Park, Grafton, ILBill Neely

Introduction

“Heaven and earth shall pass away, but my word shall not pass away.” Luke 21:331

From these words of Jesus, Theodore Parker launched into “The Transient and the Permanent in

Christianity.” In this 1841 ordination sermon, he preached that the doctrines and theologies of

various forms of Christianity are transient. He preached that beliefs accepted by one generation

of Christians are mocked by future believers, and that what one is burned for in one age is what

another is admired for later on. He preached that the Testaments themselves become idolatrous

when used as the infallible and only sources of religious truth; that they then become used as

substitutes for the one truth of “absolute religion,” which is “eternal truth of God.” He preached

that these substitutes are inevitable and explainable, but can be worrisome when we mistake their

passing flickers for the eternal flame.

He preached that even if “… Jesus of Nazareth had never lived, still Christianity would stand

firm, and fear no evil.” He then preached about what an awful thing that would be; to lose the

model of Jesus of Nazareth. Yet his argument continues: the Eternal Truth rests not on the

“organ though which the infinite spoke,” nor on the “infallible authority of the New Testament.”

Rather, the Eternal Truth, and Christianity (its best expression), “is true, like the axioms of

geometry, because it is true, and it is to be tried by the oracle God places in the breast.”

Distillations of his sermon are plentiful. A common one around what comprises the “eternal truth

of God,” can be found in this often-mentioned passage which directly follows clear delineations

of the transient (“folly, uncertain wisdom, the theological notions, the impiety of man”) and the

permanent (“the eternal truth of God”):

It must be confessed, though with sorrow, that transient things form a great part of what

is commonly taught as Religion. An undue place has often been assigned to the forms and

1 Most translations use “words.”

1

doctrines, while too little stress has been laid on the divine life of the soul, love to God,

and love to man. Religious forms may be useful and beautiful. They are so, whenever

they speak to the soul, and answer a want thereof. In our present state some forms are

perhaps necessary. But they are only the accident of Christianity; not its substance. They

are the robe, not the angel, who may take another robe, quite as becoming and useful.

The robes are the forms and doctrines. Even Christianity is a robe. The angel is the divine life of

the soul, love of God, and love of humankind; which, taken as a whole, comprises the eternal

truth of God. The robes tatter and fall apart; are stained by sin and idolatry, but the angel; pristine

and holy, always, continues stirring in the heart an awareness of love of God and love of people.

Even had Jesus never existed; even had the Church never seen the light of day, these truths

would exist and be expressed in other ways.

Parker’s sermon used the transient (doctrines, dogma, forms, Jesus) to reflect on the permanent.

He exhorted the congregation to not confuse the two; to know that in the necessary forms and

human structures of religion there may be beauty, inspiration, and guidance toward moral

edification, but they would or could pass away, and/or be replaced, and God would remain.

Moreover, if they’re pure, they themselves intend to point to something beyond themselves. And

while the forms demand much attention, they should not receive our deepest devotion.

The invitation of this paper was to consider Schleiermacher along similar lines of transience and

permanence. This, we will do, staying close to Parker’s construct: permanence through the lens

of Schleiermacher’s God, and transience through the lens of Schleiermacher’s understanding of

the role and function of doctrine and dogma. Also as invited, this paper will consider how, and if,

these avenues of thought are useful in pluralistic and non-theistic contexts. Finally, any

discussion of Schleiermacher is obviously incomplete without attention paid to the physiological

foundation that he assigns to all things religious, but as that area is covered by other writers and

respondents, this paper will try to largely avoid emphasizing that feeling is everything for

Schleiermacher.

God

2

For Schleiermacher, God is all about feeling. In The Christian Faith, he delineates the

experience of God as being a feeling of absolute dependence, which he defines as “…self-

consciousness which predominately expresses a receptivity affected from some outside quarter.”

This is balanced with the feeling of freedom, which “predominately express[es] spontaneous

movement or activity.”2 Threading the two together, dependence requires some “outside

quarter,” upon which to be dependent, as well as the freedom to respond to that stimuli. Freedom

requires activity, but moreover it requires that original impulse to which we can react. Further

and broader delineation of dependence and freedom is the subject of another paper; the point

here is to begin simply by expressing the centrality of dependence and freedom not just in

Schleiermacher’s overall thought, but specifically in his doctrines of God.

God is that object; that original, constant impulse, upon which our feelings of dependence are

experienced. Our responses to that impulse are varied. “All attributes which we ascribe to God

are to be taken as denoting not something special in God, but only something special in the

manner in which the feeling of absolute dependence is to be related to Him.”3 Schleiermacher

describes this in terms of reason, arguing that if we were to believe that God had the myriad

expressions attributed to God by those feeling dependent upon that object, God’s nature would

be hopelessly contradictory and finite, just as we tend to be. This doesn’t pass Schleiermacher’s

understanding of speculative reason.

But if we hold God as constant and our responses as finite and contradictory, that simply reflects

human nature. This explains and in a way, normalizes, the diversity of approaches to how one

knows, serves, and prays to God, or that upon which one feels absolutely dependent. The

important part is that we feel absolutely dependent upon something he, and most, call God:

So that while we attribute to these definitions only the meaning stated in our preposition,

at the same time, everyone retains the liberty, without prejudice, to his assent to Christian

Doctrine, to attach himself to any form of speculation, so long as it allows an object to

which the feeling of absolute dependence can relate itself.4

2 Friedrich Schleiermacher, The Christian Faith, (London: T&T Clark, 2004), 194 and 13-14.3 Ibid., 194.4 Ibid, 196.

3

We’ll come back to this sense of “liberty” when we discuss doctrine and orthodoxy. But first,

Cobb notes the one-sided nature of this relationship: “As creatures, we are dependent on

something that is in no way dependent on us.”5 The absolute quality of our relationship with God

provides this imbalance; one that may soothe or frustrate the faithful, depending on our

temperaments and inclinations. Cobb compares this imbalance in Schleiermacher to Whitehead’s

concept of our relationship with God which, while not being egalitarian, is more creatively

mutual:

[For Whitehead] What we become in each moment depends on what we feel. But when

what we feel is actual, it not only affects what feels it, but also is affected by what it feels.

Schleiermacher recognizes this as characteristic of our feeling of other creatures.

Whitehead believes it is characteristic of our feeling of all other actual entities

whatsoever, including what he calls, “God.” Hence, the relation to God in Whitehead is

not one of absolute dependence as Schleiermacher defines this.6

Or, on a scale of absolute dependence on the left to mutual interconnectedness on the right,

Schleiermacher is firmly to the left. Whitehead is right of center. Later reformulations of

Whitehead’s process philosophy into process-relational theology move further and further to the

right. Cobb turns many things into discussions of Whitehead, but in this case the distinctions can

be particularly helpful for a faith whose constructions of God, when they exist, tend toward the

right of this imaginary scale. Schleiermacher’s doctrine of God is different.

We see this as he describes a God of four traditional doctrines: God is eternal, omnipresent,

omnipotent, and omniscient.7 In summary of his first doctrine, after considerable attention paid

to the difficulties of describing what it means to be eternal without, because of the limits of

language, placing restrictions upon God, Schleiermacher posits a God that is beyond the category

of time, to the point of not really even being able to talk about time or infinity, because it might

5 Charles Cobb, “Schleiermacher and Whitehead on Religious Pluralism.” In Schleiermacher and Whitehead, ed. Christine Helmer (New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2004), 318.6 Ibid., 319.7 Schleiermacher, Christian Faith, 203 – 232.

4

bring to mind finiteness and God is beyond categories, or it might bring to mind change, because

things change over time, and God doesn’t change.

This becomes a bit insufferable, until Schleiermacher, in what he terms to be a “postscript” to

this mess, writes, perhaps with a wicked smile, “We may do better, therefore, to take the

principle that God is unchangeable, merely as a cautionary rule to ensure that no religious

emotion shall be so interpreted, and no statement about God so understood, as to make it

necessary to assume an alteration in God of any kind.” God is eternal and/or unchangeable, and

should one be tempted by those expressions to start imagining limits, even limits that God

surpasses, resist that profane temptation.

His second doctrine affirms that God is omnipresent, or similarly beyond the categories of space;

a “spaceless causality that conditions not only all that is spatial, but space itself as well.” God is

beyond the categories of time and space. He struggles with the same concerns about language

and the perception of putting limits upon God before reaching a “ … fundamental improvement,

one that removes the spatial element all together, namely, the formula that God is in Himself; but

of course, along with this it must be asserted that the effects of his causal being-in-Himself are

everywhere.” Schleiermacher prefers this framing because it removes spatial contrasts.

In the postscript to this doctrine, he adopts the phrase, “The Immensity of God,” which he uses in

the sense of a being that is everywhere but not in the sense that it “extends” or is spatially

constructed. He concludes by equating a sense of spatiality with a sense of being less-than

absolute, and thus less-than God-related, feeling of dependence. This is his concern with

language and with constructing his doctrines of God: that doing so will lead one to confuse the

less-than-absolute; the transient, if you will, formulations, with the permanence of God, which is

beyond every category in every formula.

His third doctrine proclaims the omnipotence of God; the fourth, the omniscience of God, both

with the same exacting attention paid to how a feeling of absolute dependency cannot be

associated with a God of any kind of partiality. There’s a wholeness, a completeness, a shapeless

divine causality that is the true nature of God and the prompt of the feeling of absolute

5

dependency that is the experience of God. Just as a feeling that is less than absolutely dependent

is not the feeling of God, thoughts that are less than absolutely unrestrained in terms of God’s

eternal, omnipresent, omnipotent, and omniscient nature are not thoughts about the true nature of

God.

This consistency is not only admirable, but essential. Without it, Schleiermacher’s doctrines of

God are unremarkable, and, in his focused statements on the nature of God, they read like

somewhat predictable responses to the metaphysical philosophers of his day. But the coherency

of how he applies his new formulation (a feeling of absolute dependence) to well-established

concepts of God, is unique. It stresses how important the absolute qualifier is. It’s not just any

feeling; it’s an absolute feeling. It’s not just any construction of God; it’s one that ultimately is

beyond every constraint. For it to be of God, it must be complete beyond the conception of

complete; whole beyond the conception of wholeness; absolute beyond the conception of

absolute. Anything less is partial; transient.

Fiorenza notes that Schleiermacher’s doctrines of God are spread throughout The Christian

Faith,8 and indeed, even after this focused treatment of God’s four main “divine attributes,” he

mentions, almost in passing, three other divine attributes: the Unity, Infinity, and Simplicity of

God. His treatment of unity leads to an understanding that if one abstracts the attribute of the

unity of God, which he previously refers to as a “virtue of which there is no distinction in

essence and existence,” and if one notes that impulses or religious excitations are individual but

aroused by an abstract commonality, then those excitations are indications of One, and not many.

Or, to put it another way, unity proclaims that the fact of religious excitations means that there is

causality, which Schleiermacher considers to be a divine causality, with speculative

manifestations in excitations. Thus unity is considered not only in the God concept itself, but in

the diverse but common excitations that arise from the concept among people. We all respond

(unity) to the same thing (unity) in different ways.

Little is added by his treatment of the attribute of infinity that isn’t previously discussed. He

emphasizes again that if it has limits, it can’t be attributed to God. His use of simplicity builds on 8 Francis Schussler Fiorenza, “Schleiermacher’s Understanding of God as Triune,” in The Cambridge Companion to Friedrich Schleiermacher, ed. Jacqueline Marina (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

6

this: “[simplicity] is the unseparated and inseparable mutual inherence of all divine attributes and

activities,” and “nothing shall be adopted which belongs essentially to the sphere of contrast and

opposition.”9 Divine attributes cannot be internally contrasting, nor can various aspects be

separated from the whole, at least not in their divine essence. Our separation of them, for

theological and discernment purposes, carries the constant risk of narrowing or limiting the scope

of God so that we can think and communicate. This risk is obviously necessary, but throughout

his formal treatments of God and the more contextual assessments that fill many paragraphs

throughout The Christian Faith, Schleiermacher shows a consistent concern with mistaking our

categories, doctrines, and ways of thinking for the sum of the divine causality itself. Indeed, he

would go on and on and on about even my use of the word “sum,” as it indicates, in some or

many ways, a boundary, and with God, there aren’t any of those. This inexpressible Ultimate is

the permanent. Every expression we have of it is changeable, temporal, and ultimately

insufficient. Every human formulation is transient.

Doctrine, Etc.

We return to words cited earlier:

So that while we attribute to these definitions only the meaning stated in our preposition,

at the same time, everyone retains the liberty, without prejudice, to his assent to Christian

Doctrine, to attach himself to any form of speculation, so long as it allows an object to

which the feeling of absolute dependence can relate itself.10

This variance, or “liberty” is true for him not only in doctrines of God, but more broadly in

dogmatic theology. He writes, “A dogmatic treatment of doctrine is not possible without

personal conviction, nor is it necessary that all treatments which relate to the same period of the

same church community should agree among themselves.”11 These two statements set up an

expectation of diversity in thought about matters of theology, creating a vibrant and changing

Church. With diversity in thought typically not being a great friend of dogma, we can start to see

Schleiermacher as appreciative and expectant of new formulations, even those that change how

9 Schleiermacher, Christian Faith. 231.10 Schleiermacher, Brief Outline of the Study of Theology, (Richmond: John Knox Press, 1970), 196.11 Ibid.,73.

7

the Church sees itself and functions. Additionally, he equates dogma, which is typically more of

an institutional tool, with being the product of personal convictions, which, from the standpoint

of the institution, would likely weaken its authority.

He expands on this by lecturing about the treatment of doctrine and dogma in the context of

conservative church leadership and how change happens:

Dogmatic theology serves the leadership of the Church, to begin with, by showing in how

many ways and up to what point the principles of the present period has developed itself

on all sides, and how the germs of improved formulations still come to relate to this

principle. At the same time, it gives practical activity that norm for popular

communication, so as to guard against the recurrence of old difficulties and confusions

and to prevent the introduction of new ones.

This latter, practical interest falls entirely within the conservative function of church

leadership, and it falls from this that the gradual cultivation of dogmatics originally

proceeded … In every historical moment which can be represented separately, that within

the doctrine which flows out of the preceding epoch comes forth as having been most

determined by the Church; but that which rather opens the way for a future course

appears as due to the work of individuals.12

These are from his published lecture notes; they’re what he was teaching students about

theology. They describe the formulation of dogmatics as something that is in the interest of the

institution. Their conveyance, from epoch-to-epoch, tends to be seen by conservative church

leaders as providing strength, wisdom, and clarity in both theology and practical church

functioning. As dogma, they’re not usually receptive to change. And yet they do change when

individuals who are not, or not as, central in the organizational power of the Church as-is,

succeed in the creation and dissemination of their “improved formulations.” That this change

from what an institution protects, and in some cases authored, toward what individuals deem

true, is not decried by Schleiermacher, may be another reason to term him, “liberal.”

12 Ibid. 73.

8

Was he liberal in terms of doctrine, dogma, and institutional change? Yes, but in a balanced way.

He expresses a value for dogmatics and an understanding of their necessity in theological

growth. Much like the object upon which subjective images are painted, dogmatics are the

foundation upon which future advances in thought are built. While he’s certainly not dogmatic in

a sense of rigidity, he does frame what is dogmatically asserted as truth in that it reflects the

principles of an epoch. Thus, he wrote and lectured from a balanced perspective about the value

for, and dangers of, dogmatics and doctrine.

Brandt writes to this, summarizing this aspect of Schleiermacher’s Brief Outline of the Study of

Theology, as such: “So theology is a practical and teleological discipline existing within a

circular relation with the church and its faith. The church is at once the ground and goal of

theology: theology arises out of the church and seeks to contribute to its ongoing life by means

of careful and critical reflection on faith and its historical manifestations.”13 Schleiermacher

understands proper theological criticism to arise from within the church itself and to be offered

in the interests of the church itself. Criticism seeks to “contribute to its ongoing life,” which by

extension, means that criticism that intends to destroy the institution is to be disregarded. In this

context, theology can be seen as a hammer used to build or destroy institutions. Those swinging

away should be clear about their intentions, as should those housed within the walls of the faith.

If strengthening is intended, perhaps more can join in, until leaders are captured by new

formulations. If destruction is intended, perhaps the hammer can be taken away, or its power can

be blunted by a larger focus on positive criticism and evolving theology.

One brief side note about those subjects of “careful and critical” reflection: “faith and its

historical manifestations.” Such reflection requires knowledge, study, and awareness of said faith

and historical manifestations. It involves not only ideas about potential theological innovations,

or the interesting strategies and approaches of other faiths and institutions, but exposure to that

which has been in the history of the faith in consideration, and why. To the extent that a faith is

shallow in terms of understanding its own history and theologies, its potential to sustainably

strengthen itself is very small. To the extent that a faith is rich with awareness of its history and 13 James Brandt, All Things New: Reform of Church and Society in Schleiermacher’s Christian Ethics (Louisville, Westminster John Knox, 2001), 34.

9

patterns of thought, its ability to build new forms that bear new wisdom, is great. That richness

comes not through the rote recitation, or empty, habitual application, of creeds, catechisms,

doctrines, or principles, but through active study, discernment, and discussion of what a faith has

been, is, and is becoming.

We see Schleiermacher’s balanced approach to tradition and change in his treatment of

orthodoxy:

Every element of doctrine which is construed in the intention of holding fast to what is

already generally acknowledged, along with any inferences which may naturally follow,

is “orthodox.” Every element construed in the inclination to keep doctrine mobile and to

make room for still other modes of apprehension is “heterodox” … The two elements are

equally important, both in respect to the historical course of Christianity in general and in

respect to every significant moment as such within its history.14

“The historical course of Christianity” can be seen as a long-shifting orthodoxy. The same

person, same God, and same scriptures are at the center of the faith even among its many

institutional representations. “Every significant moment” can be seen as events of heterodoxy

within those institutions; as times when they and their doctrines have changed. And yet, while

they have changed dramatically, the core of the faith remains about a person, a God, and wisdom

gleaned from a certain set of scriptures (albeit resulting in wildly different conclusions). This is,

perhaps, an example of the healthy dynamic between orthodoxy and heterodoxy that

Schleiermacher values, and would explain why he considers the two, what was and what is, or

what is and what is becoming, to be “equally important.” What is becoming is built off of what

is, and what is, is an institution with a history, tradition, and beliefs captured doctrines and

dogma.

The might contextualize Richardson’s assertion that young Schleiermacher was more

transcendentalist (meaning less dogmatic) and older Schleiermacher was more doctrinal

(meaning more conservative).15 Young Friederich developed heterodox thoughts aligned with the 14 Schleiermacher, Brief Outline, 74.15 See bibliography.

10

free mobility of his mind. As he aged, he applied them to orthodoxies within the Church so that

they might have a larger impact. That he was not as successful, or respected, or well-known in

these efforts is arguable, but ultimately beside the point made here, which has only to do with

orthodoxy and heterodoxy. Perhaps in the beginning, he wanted to influence thought. As he

aged, he wanted the thoughts to influence institutions.

He spent a great deal of time, after all, teaching and preaching in institutions, with an eye toward

newer, better formulations of thought. He was a heterodox thinker within orthodox institutions

(the individual is always more heterodox than the institution. Even if the heterodoxy is toward a

regressive and abandoned conservatism or fundamentalism, its advocacy for a different

formulation makes it heterodox). Perhaps this dual status led him to lecture: “Every treatment of

theological subjects as such, whatever their nature, stands always within the province of church

leadership … Even the especially scientific work of the theologian must aim at promoting the

Church’s welfare, and is thereby clerical.”16 He means “clerical” in the churchy way, not the

office work-y way, although frankly, that’s often a fine line.

Again, we must emphasize that in this case, he was lecturing to students; those who would

become leaders of Christian institutions. He seemed to teach that church leadership calls for

theological reflection that refines and strengthens the church, and that this must come from a

place of affection for and belief in the institution. For Schleiermacher, orthodoxy and

heterodoxy, used properly, can both contribute to those aims of strengthening the doctrines and

evolving the life of the institution. And religious leaders are responsible for leading those efforts.

Pluralism and Non-theism

The question of using Schleiermacher in pluralistic settings was also addressed by Cobb.

Schleiermacher wrote at a time and in a context when the supremacy of Christianity was seen as

a given. The faith was believed to be more reasoned and moral than non-western faiths

(monotheism in general was seen this way), and it was imagined that the religious enlightenment

of the human race would one day reach the far shores of the world and replace the many deities

16 Schleiermacher, Brief Outline, 22.

11

with the one Abrahamic God. Schleiermacher lived in a sense of Christian pluralism, but not

multi-faith pluralism.

And even within the monotheistic traditions, Christianity was seen as having the most evolved

and refined path to the Kingdom of God. Muslims and Jews were at best correct in the sense of

who they prayed to, and loosely correct in their Abrahamic roots, but hopelessly confused about

how to end up in God’s eternal embrace. And of course, these differences, which in Parker’s

purest lens would be differences about the robe, and not the angel, led to enormous bloodshed.

Schleiermacher’s world was far different than Parkers, which was far different than ours today,

and so simply lifting Schleiermacher’s wisdom up and dropping it into a modern, pluralistic

context would be of limited use. Cobb called such a proposition, “anachronistic,” although one

must note that anachronism is often a favored and comfortable response to dealing with the

complexities of living in a changing world.

It’s not our response, though. Some questions for applying Schleiermacher in pluralistic settings

can include: can our various robes be accepted by one another, and can we agree about

something that comprises some aspect of the angel? Schleiermacher’s focus on knowing God

through a feeling of absolute dependence could lead those who feel, or think they feel, absolutely

dependent on something, to find a common ground, at least as long as that something can be

understood in some sort of ultimate context. Those who are comfortable with many robes, many

paths, many lights, many prayers, could certainly find in a pluralistic setting use in considering

diverse approaches toward knowing the source of the feeling of absolute dependence.

Schleiermacher himself allowed for various robes within Christianity; that he wasn’t focused

beyond that faith into a more pluralistic realm is no fault of his. But it is a reason to justly argue

that his insistence on the limitlessness of God, the necessity of changing doctrines in God’s

institutions, and the belief that God is known through something as potentially ubiquitous as a

feeling, can be a unifying realm for people of different beliefs, including those well beyond

Schleiermacher’s context.

The feelings themselves could be useful in a pluralistic setting, so long as, in Schleiermacher’s

construct, the feelings return one to the inexpressible Source from which they came. Should the

12

feelings be worshipped in their subjectivity; they would become idols in place of their Source.

Should they be that which builds emotional bridges between people, they would be nice for

certain types of community and relationships but exhibit a profane ingratitude for their Source.

Should anything less than, or refined from, a feeling of “absolute” dependence be applied to the

Source, we run the risk of mistaking our interpretations and understandings of the feeling for the

feeling itself, or worse, mistaking those self-made perceptions for the eternal truth of God. None

of these outcomes would be acceptable to Schleiermacher then or now.

In a religiously pluralistic setting, to make true use of the permanence in Schleiermacher’s

constructions of God, those gathered would have to have a sense that they’ve absolutely

experienced a feeling of dependence, relate that feeling to something that they believe is of the

ultimate, (thus, seeing that God as the God of everyone there), and then continually reorient their

community back to that Source, instead of living in the subjective expressions of those gathered.

This possibility extends so far as the group is willing to define a feeling as needed, attribute it as

required, and discern it in a manner that keep God as the focus.

The invitation for this paper included specifically extending Schleiermacher into non-theistic

contexts. I confess having little familiarity with this world. My family, my work, my friends, my

life exists in a sort of theistically-optional place. Many are non-theists, many are theists, many

aren’t sure, and I’m, frankly not sure how many classify themselves. I largely don’t care, unless

someone wants me to. Lest this seem lackadaisical; it’s not. I classify myself a theist, but I don’t

think God cares.

Perhaps the extension of Schleiermacher into a non-theistic world can be useful within a few

frameworks. One is to simply ignore that Schleiermacher attributes the source of the feeling of

absolute dependence to God. One could just focus on the feeling, ask others to do the same, and

they could talk about that. There’d certainly be commonality (we all feel), discernment (how do

we know if a feeling is absolute), disagreement (I don’t think that’s absolute), opportunities to

care for one another (I’m sorry you felt that), opportunities for group cohesion (we’ve all talked

about how we feel and we’re closer because of it), and opportunities for self-reflection (having

discerned this feeling, I am changed in this way). There is obvious value to this sort of use of

13

Schleiermacher in non-theistic circles, and while he would spin in his grave over this kind of use

we don’t really have to worry about that.

Cobb17 lays out some other possible beneficial uses. On the one hand, applying Schleiermacher

in a non-theistic context would allow those gathered to refine their own thoughts. This is true

broadly; one way to better understand one’s own beliefs is to better understand another’s. Agree

or not, Schleiermacher is a deep and specific thinker and writer, and engagement with his

wisdom provokes the kind of reaction that can lead to deep discernment. Schleiermacher can

help us better understand our particularities.

On the other hand, there is something universal about being dependent upon something beyond

the self for life. Theists and non-theists alike exist not because of our own will, but because of

something well beyond us: a process, a pattern, decisions of ancestors, accidents of antiquity,

that we have nothing to do with. Understanding our sense of dependence on and

interconnectedness with a system much larger than us is a common value of our non-theistic

Buddhist friends, for example. The marvels and mysteries of science and the stars, which we

seek to understand but never fully will and certainly did not create, have hushed the minds but

inspired the pens of countless humanist thinkers. These mysteries humble us all; or at least they

should, for whether that grace was given by cells in a swamp, or the eternal truth of God, or both,

we are all recipients.

It’s in this way that while a feeling of absolute dependence may be the robe on the angel for

Schleiermacher devotees, and while the insistence that that feeling relate to something Ultimate

may be the robe for those who wish to gather in the increasingly broadening theological spirit of

our friend’s wisdom, gratitude may be the robe on the angel that we can all relate to. This may be

the robe that theistic circles and non-theistic circles and circles of theist and non-theists together

can touch, and put on, and even smooth upon the shoulders of one another. It can be worn like a

stole; worn by many, to serve many, with many differences. But common in each thread, of each

color, representing each transient image and passing truth, could be the gratitude that whatever

we are dependent upon, responds with breath.

17 Charles Cobb, “Schleiermacher and Whitehead,” 330-333.

14

Afterword

Concluding with the angel image, Parker preached, “They are the robe, not the angel, who may

take another robe, quite as becoming and useful.” Being “becoming and useful” is certainly the

in the interest of the church. It was for Schleiermacher, Parker, and is for us today. These efforts

of transience can consume us; God knows they can fill an email inbox. But that of permanence

still calls forth, to Schleiermacher and Parker, to us today, to those to come, in whispers and

cries, about the soul and its divinity, and love for what is holy, and love for humanity. Even as

there is something disquieting about how easy it is to become hyper-focused on the transient,

there’s something comforting in knowing that the permanent still calls forth, moving us to look

beyond what is “becoming and useful,” and into the Eternity that speaks, always, of love.

Bibliography

Brandt, James M. All Things New: Reform of Chruch and Society in Schleiermacher’s Christian Ethics. Lousiville: Westminster John Knox, 2001.

Gockel, Matthias. Barth and Schleiermacher on the Doctrine of Election. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Helmer, Christine, ed. Schleiermacher and Whitehead. New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2004.

Hinze, Bradford E. Narrating History. Developing Doctrine: Friedrich Schleiermacher and Johann Sebastian Drey. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1993.

Kunnuthara, Abraham V. Schleiermacher on Christian Consciousness of God’s Work in History.

15

Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2008.

Marina, Jacqueline, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Friedrich Schleiermacher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Richardson, Robert. “Schleiermacher and the Transcendentalists.” In Transient and Permanent:The Transcendentalist Movement and its Contexts, eds. Charles Capper and Conrad Wright, 212-147. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1999.

Schleiermacher, Friedrich, Brief Outline of the Study of Theology. Richmond, VA: John Knox Press, 1970.

_____. The Christian Faith. London: T&T Clark, 2004.

_____. On Religion: Speeches to its Cultured Despisers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Thandeka. “Affect Theology: a Roadmap for the Continental Gathering of Unitarian UniversalistSeminarians.” Keynote Address, 2013.

Wright, Conrad, ed. Channing, Emerson, Parker: Three Prophets of Religious Liberalism. Boston: Skinner House, 1986.

16