schmidfilm.deschmidfilm.de/sites/schmidfilm.de/files/helnwein pressemappe in... · Created Date:...

Transcript of schmidfilm.deschmidfilm.de/sites/schmidfilm.de/files/helnwein pressemappe in... · Created Date:...

-

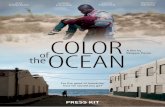

A FILM BY CLAUDIA SCHMID

THE ARTIST GOTTFRIED HELNWEIN

THE SILENCE OF INNOCENCE

-

CREDITSWRITTEN & DIRECTED BY CLAUDIA SCHMIDCAMERA SUSU GRUNENBERG SOUND JENS KRäHNKE EDITING KAWE VAKILSOUND MIxING CHRISTOF GLADECOLOUR CORRECTION DANY SCHELBYSUBTITLES RALpH SIKAU, pARABOL pICTURESpRODUCTION MANAGER MONIKA MACKpRODUCER BIRGIT SCHULzCOMMISSIONING EDITOR REINHARD WULF

pRODUCED BY BILDERSTURM FILMpRODUKTION IN COpRODUCTION WITH WESTDEUTSCHER RUNDFUNK COLOUR, pAL, 16:9, 116 MIN. ©2009

SYNOpSIS Gottfried Helnwein is an artist of clear statements, uninhibited and idiosyn-cratic. With his hyper-realistic depictions of tortured girls in the 1970s to the paintings and photographs of today, he confronts us with the dark sides of human nature. Silently but mercilessly he uses the fate of the innocent child to bring before our eyes the human capacity for suffering, making the beholder a passive, and indeed active, accomplice to injury and abuse.

It is not for nothing that Helnwein is one of the world’s best-known and at the same time most controversial German-speaking artists of the post-war period. Helnwein is an artist who thinks in political terms, analysing present and historical world events and revealing, there too, the structures of power and violence. All his life he has addressed the issue of the cruel mechanisms of the Nazi period. His pictures are an ongoing appeal against collective amnesia, deliberate or otherwise.

-

GOTTFRIED HELNWEIN “One day, during my first exhibition in the Vienna Künstlerhaus in 1971, all of my pictures were covered in yellow stickers saying ‘degenerate art’. That’s when I knew I would always have the wind in my face. It looks as if I’ve always managed to put my finger on exactly the right spot or else I wouldn’t have been able to trigger so many emotions and so much aggression and excitement as a reaction to my works. The painted picture itself cannot have been the reason because it is a fiction, two-dimensional, just a few milligrams of paint on paper or canvas, that’s all, that doesn’t hurt.

It is not my pictures people fear, it is their own pictures in their heads. My works clearly trigger something that is already present in the beholder’s subconscious. If I manage to put my finger on the right spot sometimes it makes me feel like my work has a purpose. And the day when the entire philistine society embraces me would be the day I would stop all of my artistic work. Then I’d know that I’d done something wrong.”

-

pRESS RELEASE For more than 30 years, Gottfried Helnwein has been one of the best-known and, at the same time, most controversial German-speaking artists of the post-war period. His works are in demand at the world’s most renowned museums and his exhibitions attract large numbers of visitors. Ranging from hyper-realistic depictions of tortured girls in the 1970s to the paintings and photographs of today, his work shocks, fascinates and moves a global public.

Gottfried Helnwein is an artist of clear statements, uninhibited and idiosyncratic. He almost always confronts observers with the dark sides of human nature, the manifestation of violence and power. His central theme is the child as an injured and abused being. The artist uses the fate of the child to bring before our eyes the human capacity for suffering and makes the observer a passive, and indeed active, accomplice. In his self-portraits, he represents the artist as a martyr allied with the child. His images penetrate into the subconscious and awaken the individual horror images of both the beholder’s own, and collective history. The viewer can hardly escape the fascination evoked by the detailed precision of the photography combined with the inner light of the old masters.

Gottfried Helnwein, born in 1948, grew up in the sombre Vienna of the post-war period. His childhood was marked by strict Catholicism – a world full of mises-en-scène for guilt and penitence, torture and blood, wounds and martyrdom. For him, colours initially only existed in the Catholic Church’s depictions of torture and suffering, until he discovered the colourful stories of Donald Duck and Duckburg that would change his life. Helnwein led the life of an outsider, giving repeated offence and receiving no answer to his questions about life. Society’s silence about the National Socialist period and the associated burden of guilt fascinated him even as a child. As a schoolboy, he occupied himself insistently with the National Socialist legacy and the cruel mechanisms of fascism. As an artist, he then designed an installation relating to the Kristallnacht, using children’s faces.

Gottfried Helnwein is a political artist. Confrontation with history and current politics and society pervades his entire work: global wars, Americanism, globalisation, capitalism, genetic engineering and violence in the virtual worlds are central themes in his works, which unite extreme contra-dictions: The triviality of Disney culture, for example, alter-nates with eschatological visions. The purity of the child is contrasted with horrific representations of child abuse. Despite the suffering, his later pictures exude a silence full of poetic beauty. In addition to drawing, painting, photo-graphy and installations, Helnwein has also designed stage sets and costumes for theatre and opera.

The filmmaker Claudia Schmid accompanied Gottfried Helnwein for two years and observed him in various creative processes in his castle in Ireland and his studio in Los Angeles. The film provides a sensitive insight into the intensity of the artistic process and into Helnwein’s personal environment, which also includes the friendship with the Governor of California, Arnold Schwarzenegger, who is among the collectors of his work. The combination of observation on film with discussions about art, politics and society creates a compact portrait of a radical and uncompromising free spirit of today.

-

BIOGRApHY OF FILMMAKER CLAUDIA SCHMID Claudia Schmid, born in Cologne in 1956, studied music at the Academy of Music and Performing Arts, Vienna, from 1976 to 1978, aiming at a solo career as a flautist. In 1978 she began her degree course in free art at the Academy of Applied Arts in Vienna. Four years later she transferred to the Art Academy in Düsseldorf and studied painting, sculpture and concept art under Gerhard Hoehme, Jürgen Partenheimer and Fritz Schwegler. In 1986 she was awarded the title of master pupil. Since then she has been working as a freelance artist and in 1986 she was awarded first prize, a travel grant, for her works in the context of an exhibition by the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande and Westfalen in Düsseldorf. In 1987 she received a twelve-month DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) scholarship for Italy to implement her art there, on location. In the context of various exhibitions by the Italian galleries Guenzani in Milan and Carini in Florence, she was awarded an artist symposium with project realization and exhibition in Sardinia in 1988. Back in Germany her works were also displayed by the Buchholz gallery in Cologne.

Since 1991 Claudia Schmid has been working as a freelance director and scriptwriter for WDR, Arte and 3sat. Over the years she has produced around 15 documentaries focusing on the visual arts and artist portraits. In 2003 she was awarded first prize at the Festival International du Film d’Art in Paris for her film about Werner Schroeter. She is currently working on a 60-minute film about the artist Heinz Emigholz. The film “The Silence of Innocence” is her first feature-length documentary.

CLAUDIA SCHMID – ON THE MOTIVATION TO MAKE A FILM ABOUT GOTTFRIED HELNWEIN “Already during the seventies, while I was attending university in Vienna, I noticed Gottfried Helnwein’s sketches and paintings of injured, bandaged girls. At the time I was fascinated by the technical skill and expressive power of his works, but my enthusiasm for them was held in check by the realistic manner in which he made violence and injury visible. At the time I was more interested in abstract art, which uses the translation of reality and the exploration of shape and colour. I was looking for the liberation of art from direct contents.

During the years that followed I kept visiting Helnwein’s exhibitions, but my ambivalent relationship to his works remained. It was only his 1988 installation ‘The Ninth November Night’, in which Gottfried Helnwein erected a 100-metre wall of images between the Museum Ludwig and Cologne Cathedral, that left a deep impression in me and convinced me of his approach as well as of the significance of his art. These seventeen large-scale images along the railway tracks reflected the cruelty and craziness of the extermination of the Jews in a concentrated and clear manner, so much so that this installation stayed in my memory for many years. From then on I occupied myself intensely with his entire artistic œuvre. I also gained access to his early works and recognized their radical nature.

Even though Gottfried Helnwein, who emigrated to LA and Ireland in 1996, was now world famous I hadn’t seen any exhibitions of his works for several years. When I saw a large retrospective of his works in the Wilhelm Busch Museum in Hanover and in the Ludwig Museum in Schloss Oberhausen, I was once again so fascinated by his images that I decided to make a film about him. I met the artist for the first time in his home city, Vienna, and from the moment go a deep conversation about art, politics and society unfolded. I occupied myself with Helnwein the artist and Helnwein the man for more than two years and accompanied him with my video camera during his work in the studio in Ireland and Los Angeles.”

-

Helnwein was a terrible schoolboy, who isolated himself, daydreamed and understood nothing. He was apathetic at high school too and failed every exam. He even refused to participate in art class and spent his time secretly drawing comics under his desk. As a 16-year-old he dreamed of leading a revolution to undermine the system. In 1965 he was given a “fail” and had to leave school. Since he had always been able to draw well, he attended the “Höhere Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt” (a school of draughtsmanship). During this time he was very busy drawing and livened up. However, as a protest against all norms he kept cutting his hands and face with a razor blade. He was fascinated by the “hand full of blood like a red glove” and the reactions of the people around him. He noticed that people’s behaviour changed towards those who were wounded. “The injured and the suffering are the kings of our society.” One day, during a life class he drew a portrait of Hitler, causing a great brouhaha. He was increasingly attacked and rejected by the teachers because of his stunts.

In 1969 he began his course at the Academy of Visual Arts in Vienna under Professor Hausner. Two years later he and three colleagues staged an academy rebellion. They locked professors up, set off smoke bombs, stink bombs and paint bombs and caused immense

material damage. Again and again Helnwein provoked his surroundings in order to communicate about taboo subjects, understand phenomena and find answers to his many questions.

In 1971 he founded the artist group “Zötus” and some years later the Centre for Art and Communication in Vienna. He already came to fame in his early years. During the seventies Gottfried Helnwein was mostly associated with his pictures of wounded, bandaged girls. He captivates viewers through being a master of his craft, making use of very different techniques and stylistic means. In addition to drawing, painting with watercolours, oil and acrylics and to various mixed-media techniques, photography has been one of his most important media since the 1980s. Helnwein’s pictures combine the Romantic aesthetic of Caspar David Friedrich, the radical political stance of the Viennese Actionists and the perfection of photorealists. Since the nineties he has been focusing not just on painting but also on digital photography and large-scale installations in public spaces, usually with a social or a socio-political motivation.

In the early eighties he moved from Vienna to Germany with his family and lived in a castle in the Eifel hills until 1996, whereupon he moved with his wife and four children to Ireland and Los Angeles.

BIOGRApHY OF ARTIST GOTTFRIED HELNWEIN Gottfried Helnwein, born in 1948, grew up as the son of a poor civil servant family in post-war Vienna. He felt this world to be dark and depressing: “The streets were deserted, nothing moved, nobody spoke, everything was dark and dusty, the people misshapen, bent. A world that stood still.”

He lived in a strict Catholic household in the middle of the workers’ district, which was under Soviet occupation at the time, “a Catholic island surrounded by socialists, communists and grey factories”. When he was only five he had to attend early communion and confession with his sister and received religious instruction. After confession, any childish sexuality was punished as sin. At Christmas he had to put a small stone in the manger for every bad deed and for every good one he had to stick a flower into Christ’s crown of thorns. Thereby he was “responsible for whether the baby Jesus was lying comfortably or not”. Helnwein felt Catholicism was a world full of guilt and penitence, torture, blood, wounds and martyrdom. A flagellated Christ, a Catherine broken on the wheel or a Sebastian pierced by many arrows. Holy tools of martyrdom, holy stigmata and corpses. To him colours only existed in the Catholic Church’s depictions of torture and suffering, depictions dripping in blood.

Helnwein’s parents did not play a major role in his life. He merely remembers his mother as a simple woman who spent most of her days reading Jerry Cotton novels or crime fiction on the bed and did not have much else to do with him. His grandmother on the other hand impressed and shaped him a great deal. She was clear, aristocratic, controlled everything and was almost dictatorial. She taught him through her actions not to subordinate himself and to display pride, but on the other hand she tortured him with stories of horror and war.

Gottfried Helnwein had a lonely childhood, full of fear and mental burdens, until one day his father brought him a package of Walt Disney comics. Full of excitement he absorbed the colourful stories. Donald Duck and Duckburg changed his life, stimulated his imagination and longings and were for him the only really positive counter-world.

-

It doesn’t matter how good it seems or how eloquently it was presented, it’s a position that’s non-negotiable. The problem with humans is that everything is basically negotiable and for not a lot at all. The price is incredibly low. A small reward, a small idiotic medal, any piece of praise or a raised index finger are enough and people do terrible things. Humans seem to have a great longing for a leader who tells people in black-and-white terms what to do. Then everyone can say: “That’s what I was thinking anyway,” to which the leader can respond: “I will solve this for you, we won’t put up with it any longer, we’ll put an end to them.”

Generally speaking bourgeois societies are highly satisfied when they know the mess they are living in has nothing to do with them, and they bear no responsibility. It is just that out there somewhere there are terrorists of Jews or some such group. And since people don’t generally have a memory, not a historical one, the same thing can be repeated over and over again. Nobody remembers that it only happened just recently and a lot of porcelain was smashed. Nobody knows that.

I’ve noticed that art, aesthetics, offers a way of transforming and transcending, of completely changing everything that is always part of human life, including what we think of as cruel and horrific.

GOTTFRIED HELNWEIN – INTERVIEW pASSAGES FROM THE FILM As an artist you have to seek out loneliness for yourself. That means at some point you have to overcome these conventions and go your own way. There is no way out. And for that reason artists will always be the opponents of society to a certain degree. They will always be suspicious, they will always be on the border of illegality or at least of embarrassment. That can’t be avoided. As artists live within a society and our works reflect that society, the times, the fears, the longings, the craziness, the ludicrousness, and express them through art, we still have to have one foot in society. This tightrope act, this balancing act between being outside of society in our own universe and still being in society to a certain degree is the biggest difficulty, and a Sisyphean labour every artist faces.

I believe art to be the highest form of communication that takes place through aesthetic means. This aesthetic manages to get to areas, address issues which we did not previously know existed and I think it is the job of every artist to provide an opportunity to show the world filtered through the aesthetic universe of human beings.

The fact that children are abused and tortured was something I found out relatively quickly and it really occupied me. In the sixties and seventies this was not a subject that was addressed by the media. Nobody talked or wrote about it at the time. Nevertheless I found out that thousands of children were being severely abused every year in Germany. I developed an interest in seeing the police photographs and what you see there is really terrible.

A child to me is always the chance to be someone else. When you see a child you know they are generally capable of creating and perceiving. They are incredibly sensitive. Every child is an artist.

I believe in the power of the eyes, in the magical powers every individual has to completely change reality around them. I don’t believe there is a validly defined objective condition. I think one and the same event is actually completely different events through the eyes and viewpoints of different people. It is particularly true for artists and also for children that reality can be changed all the time as you wish. If you don’t like it, you destroy it and create a new one.

The root of all evil is stupidity. The extent of human beings’ imbecility, particularly in masses, is breathtaking. Human beings know very well that it’s a crime and that it is wrong to kill. That is known. But it is very easy to convince people of the opposite. All that is needed is some ridiculous justification to drop these principles. For me there is simply never a justification or an excuse to kill or execute someone who is defenceless.

-

Over time, viewers of Gottfried’s work learn to transcend their first reading of certain pictures and to go into that magic ethereal place, and I’m impressed by how often the experience brings tears to their eyes. I’m also heartened by this strong response to the work, because even if some people claim to hate it, there is a degree of passion in their response that exposes the intensity with which they have been moved. So even people who hate the work hate it with passion. In my opinion, this is because they are challenged in a way that makes them impotent: they don’t know what to do about it, and therefore there is this reaction of anger. And anger is often the result of impotence. You are angry because you can’t do something about something.

To me, the series of works Gottfried developed called “The Angels”, in which he used images of preserved fetuses from museums in Vienna to make very large paintings and billboards, are very interesting and powerful, since we are seldom if ever exposed to that type of visual. At the same time, they are no more strange, unusual or scary than the world itself today.

I think the success of Gottfried’s work lies in its universality, meaning that there is something profound and meaningful in this work for everyone, independent of age, gender, race, location or education. There is something here that can press the hot button in everyone.

GALLERY OWNER MARTIN MULLER (MODERNISM GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCO) ON GOTTFRIED HELNWEIN To find yourself in the same room as Gottfried when he is actually painting is a fascinating experience. It is more like dance than painting. There is rhythm involved, whether he is walking backward and forward to the canvas, or sideways. It’s a choreography: all of a sudden there is syncopation and rhythm as he paints the canvas in a kind of rush and then walks away from it. So it’s really a unique experience of choreography or a dance, where the music is in your mind. And depending on the picture he is working on, and depending therefore on the type of dance, you can go from electric Miles Davis to rock’n roll to Arnold Schönberg, to all kinds of rhythms and moods and musical environments in your mind.

It is interesting to me as an art dealer to have witnessed visitors who were very angry and upset when first exposed to Gottfried’s paintings, collectors who questioned my daring in showing such works, who would then come back year after year to see the show and would finally end up purchasing a Gottfried piece. I would ask them: “What happened?” The response from a number of major art collectors has been: “Yes, at first we were horrified and challenged by the toughness of the questions raised in Gottfried’s work, but as collectors or as curators we see a lot of art, a lot of paintings every day, and somehow Gottfried’s work has always stuck in our minds, in our subconscious. We couldn’t get rid of the experience and that’s why we would revisit it over and over, until after several years or decades we slowly accessed that place, that ethereal place, that makes Gottfried’s work so unique, so powerful. And we felt the imperative to acquire one of his works.”

I think that the great genius of Gottfried’s art is its ability to transport us psychologically to a very deep inner place, both for better and for worse; a place of peace, a quiet space, where we can experience horror, pain and suffering at its worst. And I believe that one of the greatest strengths of Gottfried’s work is the ability to convey, without gratuitous shock effect, a very profound emotional experience that is triggered by the opposition or the contradiction of those two extremes evoked in the same picture plane.

-

BILDERSTURM FILMpRODUKTION GMBHFlandrische str. 250674 Kölnt +49 221 2585700F +49 221 [email protected]

WWW.BILDERSTURM-FILM.DE

CLAUDIA [email protected]

Flyer artWorK: Kathrin König • [email protected]