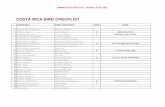

> FEATURE LOCA BIRD UIDES The importance of local bird...

Transcript of > FEATURE LOCA BIRD UIDES The importance of local bird...

O ver three days in April 2016, whilst in northern Guatemala, I saw four particularly exciting species of bird thanks to local bird

guides. Two species—Great Curassow Crax rubra and Great Tinamou Tinamus major—sparked my interest because of their global threat status (Vulnerable and Near Threatened respectively) and because of their typically elusive behaviour (partly a response to escape human hunters). The other two species were unusual (and thus exhilarating) because their migratory routes do not always include stopovers in Guatemala: Scarlet Tanager Piranga olivacea and Dickcissel Spiza americana. Just like many of you, I suspect, I might have been willing to pay US$1,500 for a one-week visit to see these birds as components of a much longer trip list. However, on this occasion, the sightings and the local bird guides, came free, because I was making a field visit to monitor a bird-based tourism project of the National Audubon Society (Audubon, a United States-based bird-conservation organisation). A lifer or two for free, whilst working: what’s not to like?!

Seeing El Petén’s star birdsA Guatemalan department well known for high-quality birding, El Petén harbours more than 300 species. These include highly sought-after regional endemics, such as Ocellated Turkey Meleagris ocellata (Near Threatened), Yucatan Jay Cyanocorax yucatanicus and Grey-throated Chat Granatellus sallaei, migratory birds that spend all or part of the winter in Guatemala such as Golden-winged Warbler Vermivora chrysoptera (Near Threatened), birds in transit that use the area as a critical stopover on their way south in autumn or north in spring such as Blackburnian Warbler Setophaga fusca, plus charismatic resident birds such as Orange-breasted Falcon Falco deiroleucus (Near Threatened).

I spent most of my visit to El Petén working—monitoring the progress of an Audubon conservation project focused on sustainable livelihoods, which educates local communities

on the importance of birds in their areas and trains local guides. This made my limited birding time all the more precious—thus raising the stakes if I wanted to see some or all of Petén’s most exciting birds. This visit, however, exceeded my expectations—thanks, in large part, to the company I held: local bird guides-in-training.

In an unfamiliar environment (such as a foreign country or even a new part of one’s own country), even the best birder may encounter some difficulty spotting birds or interpreting calls. In my view (and that of Audubon), local bird guides are invaluable in such circumstances: they are the best conduits to the birds of an area—an investment well worth the financial outlay.

Like any profession, there is clearly a spectrum of in-country bird guides. At one end there are keen novices, perhaps with very little specific bird knowledge and no English language skills. At the other end, there are fluent English-speaking birding experts, who are furthering ornithological understanding of their country or pursuing conservation projects as well as guiding foreign tourists. The former will usher you and ensure your safety, while the latter will help you get the lifers and share some insights on local culture during rest stops. Little wonder that the big bird-tour companies, with operations in numerous countries, make a beeline for such guides’ services.

Audubon is training local bird guidesOver the past year, Audubon’s International Alliances Program has been implementing a bird-based tourism initiative funded by the Multilateral Investment Fund (FOMIN) of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). The Program includes a strong focus on training community members living in and around Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs) in Guatemala, Belize, The Bahamas and Paraguay to be bird guides.

The areas where this project focuses are some of the most threatened ecosystems within the

The importance of local bird guidesSarah StewartIn the first of a series of articles by conservationists at the National Audubon Society, we learn about the US-based organisation’s programme to train local bird guides in Guatemala and beyond.

20 Neotropical Birding 19

>> FEATURE LOCAL BIRD GUIDES

selected countries. Habitat loss represents the main threat for the globally threatened species that are found within the IBAs at the selected project sites. In Guatemala, deforestation in the Maya Forest, the largest tropical rainforest north of the Amazon Basin, stretching across Belize, northern Guatemala and through Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, continues at an alarming rate, with up to 11% being lost annually (Bray et al. 2008).

Using a curriculum created by Audubon experts, regional professional guides and local partners (Bahamas National Trust, Belize Audubon Society, Vivamos Mejor, Wildlife Conservation Society–Guatemala, and Guyra Paraguay), each country is committed to improving local conservation capacity for birds through bird-based tourism by training guides to either ‘basic’ or ‘advanced’ levels (see box above), plus educating and engaging communities. The mission is two-fold: to produce incentives for conservation by creating economic opportunities through bird-based tourism and to increase community members’ awareness of the economic importance of birds and the habitats that support them. Over the long term, and on a large scale, revenue generated from bird-based tourism can secure the position of birds on the political and economic agenda of these countries, as it has already done in Costa Rica, Ecuador and elsewhere.

Birding at Tikal with Guatemala’s guidesPart of my field visit included witnessing the final session of the advanced bird-guide course in El Petén. With an average of 10 years guiding and seven years birding, the trainees (all of whom are members of Petén Birders Club; www.petenbirdersclub.com) are already accomplished in their profession. For them, progress is at the level of ‘nuances’ in bird calls and customer service. An example would be mastering the genus Empidonax or taking turns setting up and getting a telescope

on a bird then getting all nine fellow classmates onto it within one minute.

I joined course members on a short afternoon walk in the world-renowned Parque Nacional Tikal, where most of the trainees guide regularly. Tipped off about a Black-and-white Owl Ciccaba nigrolineata hanging around nearby, we went in search of it. With the guides’ awareness of the overall area as well as specific knowledge of some favourite owl resting areas in this dense forest, it didn’t take long to encounter this stunning nightbird by day. It is hard to walk away from an owl, but the guides suggested that we do since it might have been nesting—implementing ethics for birding that they had learned during their course.

Despite being Guatemala’s most-visited National Park, Tikal’s crowds thin out by late April—the end of the dry season and after the very busy Semana Santa (Holy Week). We were fortunate to be the only people on the main path when one of the guides spotted a Great Tinamou next to a large trunk about 6 m off the path. The dingy grey-brown bird merged with the similarly dusky forest floor. This large, terrestrial species may be neither fancy nor colourful, but an encounter with it is unwaveringly precious. Accordingly, we were delighted that the tinamou held its position for several minutes before striding

CONTRACTING AN AUDUBON-TRAINED BIRD GUIDE

Petén Birders Club comprises some of the best bird guides from across El Petén in northern Guatemala. They have, on average, 10 years’ experience guiding tourists in nature / Mayan archaeology and seven years’ experience birdwatching; almost all are fluent in English. Most Club members took National Audubon’s advanced bird guide course. Petén Birders Club can set up tours for individuals or groups (www.petenbirdersclub.com; e-mail: [email protected]).

BASIC VS ADVANCED LEVEL GUIDESBasic-level guide Advanced-level guide

Community level tour guide certified in his/her country to work in a single location or defined area near their community;Minimal English for communicating, but knows bird names in English for most commonly seen species; Less than 5 years birding experience; Usually guides casual birders on day trips or accompanies an advanced guide with more experienced birders.

National or regional level tour guide certified in his/her country;Fluent or advanced level English;Works independently or with tour operator;At least 5 years guiding tour groups of birders;Can guide multi-day tour groups of casual or hard-core birders.

21Neotropical Birding 19

1 Ocellated Turkey Meleagris ocellata, a colourful and Near Threatened regional endemic, is easily seen at Tikal (John Sterling).

2 Yucatan Jay Cyanocorax yucatanicus (John Sterling). Not so readily seen, this regional endemic inhabits the bajos, seasonally flooded forests of the Yucatán.

3 Grey-throated Chat Granatellus sallaei (Carlos Echeverría) occurs in dry forests in Belize, Guatemala and Mexico.

4 The eerie, drawn-out call of Great Tinamou Tinamus major (John Cahill) is regularly heard early or late in the day (or at night), but seeing this Near Threatened species is a different matter. Thanks to local guides, we succeeded!

5 Bird guides from Petén Birders Club checking out Tikal’s ‘magic tree’ (Sarah Stewart). Almost all are fluent in English, and most Club members have taken Audubon’s advanced bird-guide course.

1

2

3

4

5

22 Neotropical Birding 19

>> FEATURE LOCAL BIRD GUIDES

6 Yaxhá Mayan ruins where Audubon trains guides such as Moisés Pérez Díaz (Sarah Stewart). Yaxhá is the second most visited Mayan ruins in the Petén, and also a RAMSAR site.

7 The guides’ local knowledge helped us track down a day-roosting (and possibly breeding) Black-and-white Owl Ciccaba nigrolineata (Greg Lavaty; www.texastargetbirds.com).

8 Giant Cowbird Molothrus oryzivorus is a regular visitor to the ‘magic tree’ at Tikal. This bird (of the nominate subspecies rather than the impacificus of Guatemala) was photographed along the Transpantaneira, Mato Grosso, Brazil, August 2008 (James Lowen; jameslowen.com)

9 Rufous-tailed Jacamar Galbula ruficauda, Transpanteira, Mato Grosso, Brazil, September 2008 (James Lowen; jameslowen.com). This bird (albeit of the subspecies melanogeia) lends colour to birding at Uaxactún.

10 Advanced-level guides in Guatemala are expected to master the genus Empidonax, one example of which is Acadian Flycatcher Empidonax virescens, which migrates through the country. This bird was photographed at Dungeness, Kent, UK, in September 2015 (James Lowen; jameslowen.com).

6

7

8

9

10

23Neotropical Birding 19

silently away. Enthralled, I remained crouched until the last feather disappeared into the distance.

Granted, Great Tinamou has a large distributional range and is often heard in tropical forests, but actually setting eyes on one is nevertheless unusual. Given that tinamous are often hunted, they are rarely seen near human settlements. The local guides from El Petén are so highly attuned to Tikal’s forest environment that they filter every sound and know every corner along the trail where a particular species might be hiding out. Accordingly, despite our group numbering double figures, individual guides were able to spot birds and point them out before they were spooked.

The following day, the group of guides decided to take a look at their favourite ‘magic tree’ near the central plaza of the Tikal Mayan ruins, and took me along. In April, the tree is usually flowering. At such a time it typically attracts 20–30 bird species, such as Blue Cyanocompsa parellina, Indigo Passerina cyanea and Painted Passerina ciris (Near Threatened) buntings, Red-legged Honeycreeper Cyanerpes cyaneus, Giant Cowbird Molothrus oryzivorus, Tennessee Leiothlypis peregrina, Chestnut-sided Setophaga pensylvanica and Golden-winged warblers.

On our way to the magic tree, one of the course instructors kept saying: “Do you hear that? Do you hear that?” I confess that I couldn’t hear a thing. He imitated a very low, dull grunt. I could hear many other birds calling in the forest, but not any low notes. He assured me there was something special calling in the distance. The group of guides and the other instructor all agreed and I trusted them. Despite being able to identify common species in this type of subtropical forest, I am not familiar with all the calls. These guides have spent many years in this and other forests of the Petén, not only guiding but also doing scientific research in some cases. They know avian vocalisations well and can distinguish the variety of tones with ease.

Then a guide spotted some movement and a flash of yellow up high in the forest branches. The colour was the characteristic bill knob of a male Great Curassow perched way up on a broken branch! As with the Great Tinamou, hunting pressure in the Petén means that Great Curassows are rarely seen at close range or near inhabited areas. Seeing this cracid up high was a reminder to look at all levels in the forest for movement, even for birds that one primarily associates with the ground. Again, without local guides, I might have missed out.

We continued to the ‘magic tree’; it did not disappoint. It was dripping with tanagers and

warblers. The guides led us to one of the adjacent Mayan ruins. Here we perched on a precarious ledge that was at a great height. From here we could get a long look at the tree in all its glory. I would never have known about this particular tree had it not been for our local guides. Although close to the main plaza, the particular ruin on which we were sitting was not well visited.

Something even better came next; a great surprise. One of the guides was scanning treetops towering above adjacent nearby ruins and spotted

CASE STUDY: MOISÉS PÉREZ DÍAZHailing from Jobompiche in the Guatemalan department of El Petén, Moisés Pérez Díaz (pictured) has worked more than half his life as a park guard at Parque Nacional Yaxhá–Nakúm–Naranjo and eight years as a community tour guide. An enthusiastic participant on Audubon’s basic-level bird-guide course in Yaxhá in 2015, Moisés will easily transition to bird guiding. This will add value to his current repertoire of knowledge in Mayan archaeology and wildlife of the Reserva de la Biósfera Maya.

Moisés is a strong believer in utilising his new knowledge to increase income opportunities for himself and his family and also in sharing what he has learned with his community so they are also aware of the importance of birds to the environment. “I liked the Audubon bird guide training course, because it will strengthen my service as a community guide in Yaxhá”, he says. “If we have bird tourism here, we will have more work, more jobs. Awareness of birds is important—not only working in tourism but also in my community to convey the importance of birds so that others also get involved. If we don’t kill birds, we can keep an equilibrium and benefit economically.”

24 Neotropical Birding 19

>> FEATURE LOCAL BIRD GUIDES

something different. The guides got the scope on the bird and realised that it was a scarce passage migrant for the Atlantic slope of Guatemala—a Dickcissel. Amazingly, there was not just one—but a flock of 35. For some guides, it was a lifer and for others, it was only their second or third encounter with this Neotropical migrant. Thoroughly satisfied, the guides congratulated each other and returned back to the visitor centre to take their final exam. Birding immediately before a professional examination? That’s playing it cool!

Guides at UaxactúnTwo of the ‘advanced’ guides, a colleague and I continued to Uaxactún, a lesser known Mayan site around 45 minutes’ drive north of Tikal. Here we aimed to see how some recently trained basic-level bird guides were getting on.

Although less experienced, this particular group of aspiring guides resides within the Reserva de la Biósfera Maya and thus has on-site birding opportunities all day, every day, very close to home. One morning, we went birding without any particular objective in mind. While taking a short break on a low Mayan ruin, we saw a red bird on the top of a sparsely leaved large tree way in the distance. One of the advanced guides took a closer look and pointed out the dark wings to the aspiring guides. Again there was no doubt—this was a Scarlet Tanager. Like the Dickcissel, this is an uncommon migrant in this part of Guatemala. The local community guides that recently finished the basic level course could have dismissed it as a Summer Tanager Piranga rubra, very common in this area. The advanced guide did not.

Throughout the next two days, we spotted several uncommon species, such as Yucatan Flycatcher Myiarchus yucatanensis, Rose-throated Tanager Piranga roseogularis and Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus. The supporting cast comprised many more common colourful species such as Red-legged Honeycreeper, Baltimore Oriole Icterus galbula, Yellow-winged Tanager Thraupis abbas, Black-headed Trogon Trogon melanocephalus, and Rufous-tailed Jacamar Galbula ruficauda.

It was clear that the basic-level guides benefited from interaction with the advanced-level guides who accompanied my colleague and me. The more experienced pair served as mentors for the lower-level guides. The latter also learned by observing. By gauging the level of interest of the advanced guides in certain birds, the basic-level guides are learning differences

in the perceived ‘value’ of common versus rare birds. By understanding birding tourists’ needs (which typically relate to seeing rare birds), this continuously improving body of guides is rapidly understanding how having birds accessible to visitors might translate into income for them and their communities. And, of course, comprehending that protecting their forests is integral to that revenue stream.

Audubon and bird tourism Although I didn’t personally pay for seeing some exciting species, or indeed the 100 or so other species that complemented them, during my visit to El Petén, I was reassured about the opportunities that birds, and local birding guides in particular, provide for getting ecotourist dollars into nature conservation. Audubon’s bird-tourism program in Guatemala, Belize, The Bahamas and Paraguay is trying to explain the potential economic value of birds to local communities. Bird-guiding and related services provide tangible supporting evidence. Meanwhile, for you, as a birder, being accompanied by a local bird guide can enhance your experience and, hopefully, your life list.

Over the next few issues of Neotropical Birding, Audubon’s bird-based tourism initiative will transport you to some new birding sites in The Bahamas, Belize, Guatemala and Paraguay. Along the way, we will introduce you to some of the new professional bird guides and the high-value birds that excite them.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSI thank the Petén Birders Club and local bird guides in Uaxactún who made my visit to El Petén so enjoyably ‘birdy’, photographers who contributed images that accompany this article, and colleagues (notably Matt Jeffery and Maki Tazawa) who commented on earlier drafts of this article.

REFERENCESBray, D. B., Duran, E., Ramos, V. H., Mas, J.-F., Velazquez,

A., McNab, R. B., Barry, D. & Radachowsky, J. (2008) Tropical deforestation, community forests, and protected areas in the Maya Forest. Ecol. and Soc. 13(2): 56.

SARAH STEWARTInternational Alliances Program, National Audubon Society, 1200 18th St., NW, Suite 500, Washington, DC 20036, USAE-mail: [email protected]: www.audubon.org/conservation/international

25Neotropical Birding 19