العلاقات الحثيه مع قبائل الكاسكا

Transcript of العلاقات الحثيه مع قبائل الكاسكا

Anthropology of a Frontier Zone: Hittite-Kaska Relations in Late Bronze Age North-CentralAnatoliaAuthor(s): Claudia Glatz and Roger MatthewsSource: Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 339 (Aug., 2005), pp. 47-65Published by: The American Schools of Oriental ResearchStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25066902 .

Accessed: 30/04/2013 01:27

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

The American Schools of Oriental Research is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extendaccess to Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Anthropology of a Frontier Zone:

Hittite-Kaska Relations in Late Bronze Age North-Central Anatolia

Claudia Glatz

Institute of Archaeology

University College London

31-34 Gordon Square London WC1H OPY

United Kingdom

Roger Matthews

Institute of Archaeology

University College London

31-34 Gordon Square London WC1H OPY

United Kingdom

The northern and northeastern borders of the Hittite Empire of Late Bronze Age Ana

tolia hosted a loosely federated group of peoples known as the Kaska. Hittite texts tell

us much about the persistent state of hostility between the Hittites and the Kaska, but

there have been few serious attempts to understand the Kaska on their own terms. Here

we employ a flexible interpretive framework, rooted in frontier studies, in order to re

view the textual evidence for Hittite-Kaska relations before treating the Kaska as an

thropologically approachable subjects. Issues such as ceramics, diet, and subsistence

are explored by means of Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age evidence from a range

of archaeological sites. Finally, survey evidence from the Paphlagonia region is con

sidered in the light of Hittite-Kaska relations, and the importance of natural features as

frontiers, especially rivers, is underlined.

introduction:

looking north from hattusa

If we stand today on top of Yerkapi, the great

rampart that dominates the southern end of Hat

tusa, the capital of the Hittites, a sweeping view

unfolds below as we face north across the city (fig. 1). The entire town is laid out at our feet, the land

dropping dramatically some 300 m in height over a

distance of almost 2 km to the northern limit of the

city and the modern village of Bogazkale. Beyond the steep contours of the Hittite city lie banks of roll

ing hills and broad plains, today a patchwork of fer

tile fields traversed by streams, while beyond them

more rugged terrain dominates the horizon. From

this viewpoint, we are facing what for the Hittites

was a combustible and contested frontier zone, for

not far northward beyond these rolling hills lay the

territory of a group of peoples who caused more

trouble for the Hittites than any other through their

entire history?the Kaska. The loosely defined groups of peoples called the Kaska feature prominently in

political developments of the Late Bronze Age, es

pecially in its later centuries. Their significance for

the Hittites is indicated by the fact that they are men

tioned, as enemies, in every major historical work of

the Hittites, as well as in many treaties, religious in

vocations and prayers, oracle queries, letters, and in

structions to border commanders (von Sch?ler 1965:

10-11). The episode of imperial formation, consolidation,

and collapse that takes the form of the Hittite state is

the dominant political event of Anatolia in the sec

ond millennium b.c. From existing texts, principally from Hattusa but also from Ma?at H?y?k/Tapikka (Alp 1991), and from scattered archaeological in

formation, we already knew something of the nature

and scope of relations between the Hittites and their

northern neighbors, but no previous fieldwork had

been conducted specifically in order to investigate the archaeological evidence for these interactions.

Between 1997 and 2001, five seasons of extensive

and intensive archaeological survey, under the title

Project Paphlagonia (taking its name from the Ro

man province that covered this region), were con

ducted in the modern Turkish provinces of ?ankin and Karab?k with the aim of investigating long-term

47

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

48 GLATZ AND MATTHEWS BASOR 339

"H?9PK??S.W

*-\*A

Fig. 1. View of Hattusa looking north from Yerkapi

human settlement patterns in this distinctive array of

landscapes in north-central Turkey (Matthews, Pol

lard, and Ramage 1998; Matthews 2000) (fig. 2). A

major contribution of Project Paphlagonia has been to shed new light on Hittite-Kaska relations and to

generate and explore an important case study within a contested imperial frontier zone. Across the entire

survey region, covering some 8,500 km2, about 30

sites of Late Bronze Age date were located, identi

fied as such by the presence on their surfaces of ce

ramics known from excavated sites in central Tbrkey to date to that period (definitive dating of these sites

within the second millennium is in progress and will

be featured in the forthcoming final publication of

the fieldwork).

Output from these researches, as regards the Late

Bronze Age, will be tripartite: (1) a full presentation of archaeological data and interpretations in the final

report on the field project, currently being compiled and completed by a range of contributors, and to be

published as a monograph by the British Institute of

Archaeology at Ankara; (2) a study of the historical

geography of north-central Anatolia in the Hittite pe riod with reference to possible localization of known

toponyms, currently in preparation by the authors; and (3) a historical and anthropological approach to

the Hittite-Kaska frontier zone in the Late Bronze

Age. The present article addresses the third of these areas of research and has the following aims:

to construct a conceptual framework for ap

proaching north-central Anatolia in the Late

Bronze Age, to review the historical evidence for Hittite

Kaska interactions, to employ an anthropological approach to the

Kaska peoples, and to review the nature of Hittite-Kaska relations in

the light of archaeological results from Project

Paphlagonia.

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2005 ANTHROPOLOGY OF A FRONTIER ZONE 49

Fig. 2. Map of Anatolia, showing extent of Project Paph

lagonia survey region.

CONCEPTUAL AND PHYSICAL

frameworks: FRONTIER STUDIES

AND NORTH-CENTRAL ANATOLIA

Concomitant with a burgeoning interest in empire studies, frontiers and borders have received increas

ing archaeological and historical attention in recent

years, as researchers have recognized that processes of cultural definition and hybridization occurring in

such regions can shed light on broad issues of so

ciocultural practice and identity. The region of Inner

Paphlagonia, encompassed by the modern provinces of ?ankin and Karab?k, is an ideal arena for the ex

ploration and application of approaches to the study of frontier issues. At the tectonic level, the region is

traversed by still-active faults, in particular the North

Anatolian Fault Zone, which shape the associated

geology and geomorphology. Geographically, Inner

Paphlagonia spans the transition from the rolling

steppe of the Anatolian Plateau, stretching far to the

south, to the severe mountain ranges of the Pontic

region to the north (fig. 3). Several major rivers, in

cluding the Kizihrmak (Hittite Marassantiya) and

the Devrez ?ay (probably Hittite Dahara) (fig. 4), cut

through the region, further strengthening its capacity to function as a border zone. Through many periods of its past, there is ample evidence that the region fulfilled its role as a contested frontier zone. But it

is especially during the Late Bronze Age, with the

Hittite Empire at the height of its powers, that it is

possible to track the intricacies of a complex relation

ship between an imperial power and one of its imme

diate neighbors, the Kaska peoples. How best might we conceptualize and research this relationship?

Border and frontier studies have become increas

ingly sophisticated in recent years and now encompass a broad range of approaches (De Atley and Findlow

1984; Kimes, Haselgrove, and Hodder 1982). A recent

review article by Lightfoot and Martinez encourages a view of frontiers not so much as clear-cut bound

aries between neighboring communities, but rather as "zones of cross-cutting social networks" (Light foot and Martinez 1995: 471). Prominent traits of

such a framework, as identified by Lightfoot and

Martinez, include a merging and blurring of material

culture traits at boundary zones, the existence of so

cial and political networks spanning communities on

both sides of borders, and the development of seg mentai and factional groups within such communi

ties. The aim here is to demonstrate that such a model, characterized by fluidity, overlap, and persistent com

promise, most accurately encompasses the situation

of Inner Paphlagonia in the Late Bronze Age. In sub

sequent sections of this article, we consider how the

historical and archaeological evidence sits within

such a framework.

The predominance of a colonialist perspective in

frontier studies, broadly identified by Lightfoot and

Martinez (1995: 473), has hitherto been unquestioned in the case of relations between the Hittites and their

neighbors, the Kaska. One reason for this is that all

the textual, and almost all the archaeological, evi

dence originates from the Hittite side of the relation

ship. Not only are there no texts from the Kaska side, but there are almost no excavations that reveal the

nature of their settlements, cemeteries, and material

culture. It is hardly surprising, then, that terms such as "aggressive," "wild," "barbarian," and, more origi

nally, "nemesis from the north" (Gorny 1995: 80) are

routinely used to describe the Kaska in the light of

Hittite history. It is because the Kaska can only be seen through the lens of Hittite history, using Hittite

primary sources, that such terms seem appropriate. Were it possible to write a Kaska history independent of Hittite sources, doubtless the Hittites would seem

to be the aggressors, destroyers, and intruders on the

Kaska stage. Our inability to compose such a history, and to compare it with the familiar Hittite version, should not prevent us from attempting to construct a

more balanced and nuanced view of the intricacies of

the Hittite-Kaska relationship.

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

50 GLATZ AND MATTHEWS BASOR 339

<mmusmwy&

. .. jpm^BpuiaiaBiii???itaEkjaKiiJ?mHL '

Fig. 3. Paphlagonian landscape.

The Hittite historical sources make clear the spe cial nature of their frontier with the Kaska peoples,

differing in many respects from other Hittite borders

with great powers such as Egypt and Mittani. With

the Kaska, there was no possibility for the Hittites

to deal with a single, all-powerful leader for, as we

shall see, Kaska society was not structured in that

way. Furthermore, there is no indication in the Hittite sources that the Kaska ever accepted an imperial way of life dominated by Hattusa, unlike regions and

polities to the south and east. In territorial terms, the

Hittite-Kaska frontier was essentially static, a no

man's-land of constant mistrust and mutual misun

derstanding at the most basic levels. Coping with

such a frontier made exiguous demands on the po litical and military structures of the Hittite state.

THE HISTORICAL EVIDENCE

FOR HITTITE-KASKA INTERACTIONS

The Hittite state is characterized throughout its

existence by dramatic swings in its fortunes, with the

total territory under its control fluctuating wildly in

extent within sometimes brief time-spans. The em

pire appears to teeter on the brink of collapse at sev

eral points in its history before a total, irrevocable

collapse at the end of the Late Bronze Age, around

1200-1180 B.c. One undoubted factor in this impe rial fragility was the proximity of the Hittite's capi tal, Hattusa, to the vulnerable northern frontier of the

empire where the Kaska had their home, barely three

days' march away (Bittel 1970: 11). Rich textual evidence, principally from Hattusa,

supported by occasional archaeological evidence,

provides a detailed picture of the nature and range of interactions between the Hittites and the Kaska

over a period of several centuries. From the written

sources, whose appreciation is subject to the reser

vation that they originate exclusively from one party in a two-party dialectic, it is possible to reconstruct

several elements in the structure of this fraught re

lationship. First, it is clear that there was consider

able variability in the ways that the Hittites sought to

deal with the Kaska problem. Hittite approaches to

the Kaska veered from attempts at total domination,

including military conquest, to efforts to agree and

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2005 ANTHROPOLOGY OF A FRONTIER ZONE 51

mm .i;:il"i; :':! "'*' n'^<***^^;^*^fi:fi

^{;?S^?

Fig. 4. View of Devrez ?ay-Dahara River.

sign treaties establishing mutual rights and obliga tions between the two parties. Second, the well

attested frequency of Hittite campaigns against the

Kaska throughout the duration of the empire indicates an overall failure of any Hittite policy ultimately to

eradicate the Kaska problem. Third, despite that fail

ure, the Hittites did largely succeed, through tireless

campaigning and other procedures, in establishing a

delicate balance of power in north-central Anatolia

that endured for several centuries, with some fluctu

ation around a fragile equilibrium. At the base of and permeating this relationship lay

a Hittite sense of self-identity. (We can say almost

nothing about Kaska sense of self-identity, due to

the Hittite origin of the textual sources.) While argu

ably seeing themselves as strangers in a strange land

(Van De Mieroop 2000: 138; contra Gurney 1979:

153), the Hittites defined their social identity not so

much in terms of shared language, culture, or his

torical experience, but more by their physical geo

graphic context, expressed in the term "people of the

land of Hatti" (Bryce 1998: 19). Gurney (1979: 153) has pointed out that the term "Land of Hatti" may

equally be rendered "Land of the city Hattusa" as

"Hatti appears to be nothing but an Akkadian allo

graph of the name Hattusa," unequivocal evidence

for the supreme role of the capital city as an emblem

of the Hittite state. This strong sense of geographical attachment lent a singular importance to the core

region of the Hittite state as a defining context and

motif for the state. The core area included not only the capital city and its hinterland, but a broad and

ill-defined (for us and perhaps also for the Hittites) swath of territory in central Anatolia, partly en

closed by the great Marassantiya River (today the

Kizilirmak). Conceptually attached to the core re

gion, and therefore of equal significance, were adja cent frontier zones and scattered holy cities, some of

which, such as Nerik, lay well beyond the physical borders of the core region (Haas 1970; Din?ol and

Yakar 1974; Houwink ten Cate 1979; Macqueen

1980). The location of Nerik within territory almost

always under Kaska control, along with its im

mense cultic importance to the Hittites as home of

the Storm-God of Nerik (frequently a divine witness

to Hittite treaties; Beckman 1999: 7), is a fundamen

tal structuring principle of the Hittite-Kaska relation

ship, at least as perceived in royal circles, and one

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

52 GLATZ AND MATTHEWS BASOR 339

Fig. 5. View of Kizihrmak-Marassantiya River.

that can only be appreciated by accepting the signif icance of cultic practice in Hittite daily life.

The Hittites' sense of belonging to a core region manifested itself in attitudes toward non-Hittite lands.

Such lands could be either friends or enemies: "neu

trality was not an option" (Beckman 1999: 1). The

land of Hatti, the Hittite core region, lacks sharply de

fined physical boundaries. The Marassantiya can be

forded without difficulty at almost any point (fig. 5), and challenging mountain ranges occur only well

to the north, beyond effective Hittite control during most periods. The openness of the land of Hatti was

particularly significant as regards the location of Hat

tusa, hundreds of kilometers away from the sophisti cated subject territories of the south and the associated

trade routes of north Syria, Upper Mesopotamia, and

the Levant. Cultic attachment to their capital city, home to a thousand gods, and its surrounding sacred

landscape, appears to have kept the Hittites pinned down in a region open to attack from several sides, and especially from the north, the home of the Kaska.

The intention here is not to itemize and address

every textual attestation of Hittite-Kaska interac

tion (for which see von Sch?ler 1965; Klengel 1999). The aim in this section is to provide an overview of

modes of interaction, which can serve as an inter

pretive device for approaching the archaeological evidence of Paphlagonia in the Late Bronze Age. Table 1 presents a synthesis of textually documented

Hittite strategies on the Kaska frontier. More or less

constant military campaigning and pursuit of appro

priate cultic practices, including animal sacrifice, is

attested for the entire period. These activities can be broadly grouped in three

overlapping categories:

1. Military/strategic

Campaigns led by the king or his proxy from

Hattusa into Kaska territory Foundation and maintenance of garrison towns, and system of routes, outposts, and watchtowers

in the frontier zone

Capture and fortification of Kaska-held towns in

the frontier zone

Forced exaction of agricultural and other tribute

from Kaska areas under Hittite control

Attempts to recapture, rebuild, and reoccupy the

holy city of Nerik (located within Kaska territory) Fortification of Hattusa and other towns in the

core region Relocation of the capital from Hattusa to a safer

region in the south (Tarhuntassa)

2. Diplomatic

Attempts to agree on political concessions and

treaties with Kaska leaders, including safe pas

sage to Nerik for Hittite cultic processions, the

banning of Kaska from entering border towns

such as Tiliura, the granting to the Kaska of spe cific grazing rights within the frontier zone, and

the occasional acceptance of Kaska settlement

within Hittite territory

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2005 ANTHROPOLOGY OF A FRONTIER ZONE 53

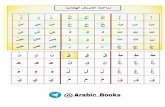

Table 1. Chronological Overview of Hittite Attempts to Deal with the Kaska

King Strategy/Events Source

Old Hittite Kingdom, 1680-1450 B.c.

Hantili I (II?) Fortification of Hattusa; "Sammeltafel" (CTH 11), Empire-period copy

Building of garrisons; Treaty of Hattusili III and Tiliura (CTH 89)

Telipinu Last king to reach towns close to Nerik; Extensive Annals of Mursili II (CTH 61)

Middle Hittite Kingdom, 1450-1380 b.c.

Tudhaliya I (II) Arnuwanda I

Tudhaliya II (III) &

prince Suppiluliuma

Military campaign;

Oaths of Kaska leaders;

Agreements with Kaska;

Instructions for officials and

Grenzherrn (border chiefs);

Instructions about civil and

military measures against Kaska,

who steal cattle and wine and

threaten Hattusa and Upper Land;

Regular military campaigns;

Repopulation of fortified frontier

towns;

Annals of Tudhaliya (CTH 142)

Prayer of Arnuwanda and Asmunikkal (CTH 375)

Oracle (CTH 137) Treaties (CTH 138-40)

(CTH 257, 260-61)

Masat texts (Alp 1991)

Deeds of Suppiluliuma (CTH 40)

Deeds of Suppiluliuma (CTH 40, frg 13)

Empire period, 1380-1200 b.c.

Suppiluliuma I Fortification of Hattusa;

Resettlement of border regions;

Mursili II Garrisons;

Resettlement of Tiliura;

Muwatalli New capital at Tarhuntassa;

Hattusili, petty king of Hakpissa;

Hattusili III Fortification and repopulation of

frontier;

Regulation of interaction

with "friendly" Kaska;

Treaties regulating Kaska access to

Hittite towns;

Use of Kaska to usurp Hittite throne

Deeds of Suppiluliuma (CTH 40, frg 28)

Ten Year Annals of Mursili II (CTH 61)

Treaty of Hattusili III and Tiliura (CTH 89, Vs II 3)

Treaty of Hattusili III and Tiliura (CTH 89)

Apology of Hattusili III (CTH 81,11)

Attempts to maintain political and military agreements with potential allies in the north-cen

tral region

Appointment of governors in buffer regions of

Pala-Tumanna

Use of "friendly" Kaska to police the frontier

zone and for internal political ends, including re

cruitment of troops from Kaska regions

3. Demographic

Slaughter of Kaska population in captured areas

Shift of Kaska population to other regions

Repopulation of abandoned towns in the frontier zone with Hittite subjects or transport?es from

elsewhere in the empire

Hittite tactics in dealing with the Kaska are illu

minated by the archive of 200 texts of early 14th

century b.c. date from Ma?at/Tapikka (Alp 1991),

mainly letters from the Hittite king to officials and

commanders living at the site. These letters are strik

ing in demonstrating the involvement of the king in

the fine detail of guarding and securing a relatively small and remote border town against the constant

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

54 GLATZ AND MATTHEWS BASOR 339

threat of attack from the Kaska. Regular activities

undertaken by the garrison commander included post

ing sentries along roads, closing gates at night, main

taining the fortifications, and providing food, water, and firewood. The letters hint at the grim realities of

life in a frontier garrison town: a commander, using a hunting term, boasts of "bagging" 16 Kaska pris oners (Hoffner 2002: 67). Some captives are de

scribed as being blinded after capture and then set

to hard labor in mills, an indication of the often se

vere consequences for the Kaska of capture by the

Hittites. Others are listed along with the ransom re

quired for their release. Thus, a certain Tamiti of

Taggasta, "who can see" (i.e., has not been blinded), has a ransom price of two boys and one man (Hoffner 2002: 67). The ransoms include animals, usually oxen and goats, but interestingly never pigs (see be

low). There can be no doubt that Hittites captured by Kaska had an equally hard time of it, and there is evi

dence for temple personnel serving as slaves for the

Kaska (von Sch?ler 1965: 72). Within military and social contexts, there is con

siderable evidence for fluidity and mobility between the Hittite and Kaska sides. An individual called

Kassu appears to be a Kaska turncoat who rose to a

position of authority in the Hittite army (?nal 1998). Texts from the reign of Hattusili III (reigned 1267

1237 B.c.) indicate that Kaska men could serve as

troops in the Hittite standing army, although there were restrictions on their movements. In that capac

ity they might serve on campaigns or be put to labor

in military construction projects such as roads or

fortification work (Beal 1992: 42-43). Hittite tex tual references indicate that the Kaska maintained a

standing force of regular troops, which could be sup

plemented by levies when required (Beal 1992: 68

69). The Hittites themselves acquired Kaska troops for the Hittite army as contributions from conquered

provinces; provinces that failed to provide agreed quotas of men were punished (Beal 1992: 82). Such

Kaska conscripts could be deployed against other

Kaska forces. Other obligations imposed by the Hit

tites on subjugated Kaska territories included a re

quirement to fight any hostile force marching through their land and to assist the Hittites in repulsing en

emy forces (Beal 1992: 124). Some Hittites fled from

the Hittite state and lived with the Kaska (von Sch?ler

1965: 72). There they must have met with Hittites al

ready held prisoner or there of their own free will.

Texts make it clear that there were "relatively close

political, commercial and social dealings between

Hittites and Kaskans in the region as a whole" (Bryce 1986-87: 92), and in treaties there seems to have

been provision for some Kaska traders to enter Hit

tite towns to conduct their business.

Within Hittite society, the overriding significance of the great king of Hatti is indisputable, "the linch

pin of the universe, the point at which the sphere of

the gods met that of human beings," as he has been

aptly characterized (Beckman 2000: 135). It is this

linchpin role, incapable of delegation, that underlies the king's intimate and exhaustive involvement in

every aspect of the attempt to keep the Kaska at bay, as the Ma?at/Tapikka letters show, and in almost

every military campaign into the harsh mountains to

the north and northeast of Hattusa on an almost an

nual basis.

It is important to stress the small window of op

portunity for military campaigning by the Hittites

(Houwink ten Cate 1984: 63). The severe weather of

the north restricted campaigns to a few months in the

late spring and summer, a season when manpower

was also in heavy demand for the annual harvest and

for mud-brick manufacture (with freshly available straw and sufficiently mild weather to dry the bricks).

Current efforts at reconstructing a section of the

city-wall at Hattusa, under the direction of Dr. J?r

gen Seeher, are shedding new light on the mechan

ics and exigencies of mud-brick manufacture and wall

construction. This annual concatenation of demands on human labor?campaigns, harvest, construction?

may help to explain the considerable evidence for a

Hittite concern with storage. The storage of large

quantities of commodities, such as water and cereal, as attested by silos and reservoirs at Hattusa and

elsewhere (Seeher 1997: 320-3), would provide an

element of flexibility in the distribution of human labor across the spectrum of tasks at any time.

Once on campaign, the Hittite army would carry with it bulk supplies of bread, flour, and other com

modities (Beal 1992: 130), which may have been

supplemented in some cases by supplies maintained

at so-called seal house cities of grain (Beal 1992:

131). Such supply centers, administered by an offi

cial (AGRIG) accountable directly to the king, ap

pear to have been restricted to the core provinces of the Hittite state, and their military, as opposed to

cultic, significance is not at all clear (Singer 1984). While hesitating to see any of the newly discovered

Late Bronze Age sites in Paphlagonia as "seal house

cities of grain," it is worth commenting on the fact

that all of them are located in close proximity to

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2005 ANTHROPOLOGY OF A FRONTIER ZONE 55

natural sources of water, in the form of springs or

streams, with ample expanses of arable land adjacent to the site. Each town would have been capable of

producing food and water and perhaps of storing these commodities for the benefit of themselves but

also of an army passing through, which might num

ber several thousand strong (Beal 1992: 283). The

Hittite army marched with a considerable baggage train, including ox- and horse-drawn carts, donkeys

carrying fodder, water, supplies, and no doubt tents

and basic domestic equipment. It was precisely such

baggage that Mursili II left behind at Altanna when

he made his night march against one element of a

major Kaska force (von Sch?ler 1965: 48). An army on the move, and led by the king, would also be

carrying with it all the paraphernalia of the royal

camp, sufficient to maintain the dignity and sacred

aloofness of the king even while on campaign (Bryce 2002: 15).

The brevity of the campaigning season and the dif

ficulty of the terrain meant that objectives in the north

had to be limited. Most annual campaigns involved

attempts solely to recover territory lost in the months

since the previous campaign and to reopen routes of

communication and supply. Only Hattusili III and

Tudhaliya IV appear to have tried to expand their

campaigns into major incursions into enemy terri

tory, attempts doomed to failure by the inability of

the Hittites to maintain adequate supply lines over

such an inhospitable and extensive landscape (Yakar and Din?ol 1974: 98).

Two historical fragments appear to refer to watch

towers, and they are frequently mentioned in the In

structions for the Commander of the Border-Guards

(Houwink ten Cate 1984: 65). One text reads, "Let

the scouts [occupy] the look[-outs] on the main road.

[As they] scanned the forefield down from the town

?[after they occupy the look-outs] let them ca[re

fully scan] the forefield [from there likewise]"

(Goetze 1960: 69; KUB XIII 1 i 12-14). Another

states, "Then let the scouts who hold look-outs re

turn to the town, bolt the gates and exits and let down

the bars" (Goetze 1960: 70; KUB XIII 1 i 23-28), and "Whereas the roads are covered, the scouts will

bring word immediately they see a sign of the enemy" (Goetze 1960: 71; KUB XIII 2 i 5-6). These refer

ences demonstrate that a systematic and careful orga nization of guards and lookout posts was an integral feature of the Hittite defensive frontier against Kaska

attack and incursion. They also reveal that scouts

were deployed at dawn in the landscape around Hit

tite border settlements before farmers and their ani

mals were given the all-clear to proceed to their

agricultural holdings for the day's labor and grazing. We can assume that lookout posts or towers, proba

bly manned day and night (Beal 1992: 270), were

situated on high ground with maximum visibility over roads and approaches to and from frontier set

tlements. Not surprisingly, lookouts were also em

ployed by Kaska forces, as the following lines from

the Annals of Mursili II make clear: "Because their

[the enemy's] lookouts were standing [at their posts], and because, if I had tried to surround Pittagga talli, Pittaggatalli's lookouts would have seen me, and he would not have waited for me, but would have

slipped away before me . . ." (Beal 1992: 265). Hittite-Kaska interactions in military and diplo

matic contexts, as textually attested, seem well de

scribed by Lightfoot and Martinez's phrase (1995:

471), "zones of cross-cutting social networks." There

is evidence for mobility between the two sides as

well as for one party recruiting factions of the other

side for its own ends. It is highly probable that other

aspects of social fluidity between Hittites and Kas

ka, such as intermarriage and peaceful cohabitation, were commonplace and, for that very reason, failed

to find their way into the highly attenuated historical

record.

AN ANTHROPOLOGY

OF THE KASKA PEOPLES

As mentioned earlier, it is difficult to construct a sense of Kaska self-identity, or even to evaluate

whether such a concept has any meaning, largely due to the Hittite origin of the relevant texts that are the

only written source for the Kaska. The potential for

bias in such a one-sided source base need hardly be

stressed, but must be kept in mind (von Sch?ler

1965: 1). With due caution, however, it is possible to glean some hints concerning Kaska society from

those same sources. In the Annals of Mursili, for

example, we learn that "Pihhuniya did not rule in the

Kaskan manner. But suddenly, where in the Kaskan

town the rule of a single man was not (customary),

Pihhuniya ruled in the manner of a king" (Bryce 1998: 215). This text suggests that the norm for

Kaska rule was through loose consensus rather than

domination by a single leader. In the late 14th-cen

tury text, the Deeds of Suppiluliuma, Mursili II de

scribes how the Kaska were organized into 12 tribes

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

56 GLATZ AND MATTHEWS BASOR 339

(G?terbock 1956: 67). Additionally, in the Hittite

view, the Kaska were grouped into three distinct re

gions (von Sch?ler 1965: 61-62): western, central, and eastern (the focus of Project Paphlagonia coin

cides with the western Kaska zone). The Kaska were capable of putting a sizable

military force into action: 5,000 to 9,000 warriors, with up to 800 chariots, are typically mentioned in

Hittite texts. Larger armies were pulled together from several tribes (von Sch?ler 1965: 73). The so

cial and political structures necessary to bring these

forces together and coordinate their arming, training, and deployment should not be underestimated. The

tendency toward cohesion among scattered Kaska

groups was doubtless stimulated and developed by the very presence of Hittite armies on a regular basis.

According to the Hittite texts, Kaska sites were often

protected by fortifications but also took advantage of the natural defenses afforded by the largely moun

tainous terrain.

The social structure of the Kaska shaped the ways in which the Hittites could deal with them, in war

and peace. In war, it proved impossible for the Hit

tites to engage a significant proportion of the Kaska

forces in battle and thus to deal a fatal blow to their

total military capability. A defeat of one Kaska force

would be followed by attack from another Kaska

force. It is notable that the only Kaska leader known

to have engaged in open battle with the Hittites, the same Pihhuniya mentioned above, was also the only

Kaska leader to rule "in the manner of a king" (Bryce 1998: 215). He thus ruled like a Hittite king and

fought in battle like a Hittite king. Unsurprisingly, he lost the battle and his kingship at one and the

same time. But Pihhuniya was the exception, and

other Kaska rulers kept wise counsel and fought their

battles at places and times of their, not the Hittites',

choosing. While not at war, treaties agreed to by the

Hittites with one element of the Kaska tribal confed

eracy need have had little currency with other ele

ments. Hattusili Ill's attempt to accommodate and

exploit some Kaska as "friendly," using them in his

usurpation of the throne, was hardly a lasting solu

tion to the problem (von Sch?ler 1965: 58-59).

Many Kaska towns are mentioned in Hittite texts

using the designate URU (town) (von Sch?ler 1965:

75). Most of them are not likely to have been major urban centers, and none of them will have remotely

approached Hattusa in scale or complexity. Kaska

towns were frequently destroyed by the Hittites but

appear to have been rapidly resettled or rebuilt else

where. This considerable flexibility in settlement lo

cation and continuity makes Kaska settlements hard

to locate archaeologically, even apart from problems in identifying Kaska material culture, as discussed

below.

Historical ignorance of Kaska identity is well

matched by the state of our archaeological knowl

edge of the Kaska. Early explorations by Burney (1956) located possibly relevant sites in the north

central region, to some extent expanded on in Sam sun province and elsewhere by Yakar and Din?ol (1974); however, work specifically targeted at issues

of Kaska archaeology has been minimal. Excavations

at Kimk-Kastamonu (Emre and ?inaroglu 1993; Gates 1997; Bilgen 1999) have revealed an inten

sive level of metal production, including metalwork

ing kilns, that may tentatively be associated with a

Kaska presence, but without publication of associ

ated pottery it is not possible to date or situate this

site precisely within a broader cultural milieu. The

famous hoard of silver items from this site (Emre and

?inaroglu 1993) need not indicate a Hittite presence, as we know from texts that the Kaska frequently looted such items from Hittite temples and carried

them off to their mountain strongholds (Goetze in

Pritchard 1969: 399-400).

Apart from the possibility of Kimk-Kastamonu, no Kaska sites have been excavated, no cemeteries

have been found (Yakar 2000: 300), and there is little

clue as to what constitutes a Kaska material culture.

As Genz (2003: 189) has recently put it, "The prob lem is that we do not know what the Late Bronze

Age pottery in the Pontic mountains looked like, whether it looked like Hittite pottery, or whether it had a tradition of its own." In fact, the position is

even bleaker: we do not even know whether the

Kaska were using pottery at all. One suggestion is

that the Kaska assumed a material culture identity from the Hittites and are therefore archaeologically

indistinguishable from them (?zsait 2003: 203), but

this argument fails to account for the lack of typical Hittite pottery over much of the Pontic region in the

Late Bronze Age, in regions known from texts to

have been inhabited by Kaska.

The lack of excavation of Kaska sites dating to

the Late Bronze Age necessitates an indirect ap

proach to the archaeological question of Kaska iden

tity. It has been reasonably argued that the Kaska were involved in the final collapse of the Hittite

Empire around 1200-1180 B.c. (Bryce 1998: 379). It

remains unclear, however, whether or not we can as

sociate traces of Early Iron Age occupation among the ruins at Hattusa, on B?y?kkaya, with an ephem

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2005 ANTHROPOLOGY OF A FRONTIER ZONE 57

eral Kaska presence at the site (Genz 2003: 189).

Perhaps the most rewarding means of approaching the Kaska of the Late Bronze Age is to accept as a

working hypothesis the interpretation that Early Iron

Age materials found at Hattusa might have some re

lation to a Kaska presence and could therefore in

form us on Kaska society. This hypothesis is at least

tentatively supported by the fact that the pottery typi cal of the Early Iron Age at Hattusa does occur in the

region to the north, in the area where we might ex

pect to find Kaska in that period (Yildinm and Sipahi 2004: 310). What might be learned about the Kaska

by approaching them through the material of the

Early Iron Age? The first concern is the pottery. Early Iron Age pot

tery at B?y?kkaya is handmade and crude. In many

respects, it is remarkably similar to pottery of a much

earlier era, the Early Bronze or even Chalcolithic

period. Either the inhabitants were reviving age-old traditions of pottery manufacture, and presumably use, after the collapse of the Hittite Empire, or those

traditions survived unchanged throughout the impe rial episode of the Late Bronze Age. In other words, a tradition of simple handmade pottery may have con

tinued in north-central Anatolia alongside the new

technology of fast wheel-made pottery introduced

and widely adopted during the Middle and Late

Bronze Ages. We may be mistaken in assigning all

simple handmade wares to the Early Bronze Age or

earlier, as the B?y?kkaya evidence clearly indicates.

It is possible that some of these wares belong to the

Middle and Late Bronze Ages and in particular that

elements of them may characterize a truly Kaska

assemblage of material culture. Without excavation

of a site deep in Kaska territory and independently datable to the Late Bronze Age, we cannot be sure

either way.

Apart from the pottery, the Early Iron Age evi

dence from B?y?kkaya has further points of inter

est. In their article on faunal remains from Late

Bronze Age and Early Iron Age levels at Hattusa, von den Driesch and P?llath (2003) delineate three

major areas of contrast between the faunal assem

blages of the two periods at the site: an increase in

the representation of pigs in the Early Iron Age lev

els; a new practice of eating equids in the Early Iron

Age; and a size reduction for both cattle and sheep in Early Iron Age levels. What might be the cultural

significance of these three developments? Let us

examine each in turn.

One of the few Hittite verbal characterizations of

the Kaska calls them "swineherds and weavers of

linen" (Plague Prayer of Mursili; see Goetze in Prit

chard 1969: 396). Other texts indicate that the Hit

tites tried to keep pigs away from cultic structures

and practices (?nal 1998: 26), and we have seen

above that pigs do not figure in the Kaska ransom

lists from Masat/Tapikka (Hoffner 2002: 67), which

suggests that the Hittites were not eager to receive

pigs as ransom. Nor are pigs listed as valued ani

mals in texts such as the Prayer of Arnuwanda and

Asmunikkal (Goetze in Pritchard 1969: 399), where

fattened oxen, cows, sheep, and goats are all men

tioned. The fact that the proportion of pig in the fau

nal assemblage at B?y?kkaya more than doubled

from the Late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age? while admittedly still only a minor representation

(up from 2.4 to 5.4 percent)?suggests a shift in at

titude to this animal. We should keep in mind other

interpretations, however, such as the different scale

and extent of the Early Iron Age settlement as com

pared with the Late Bronze Age settlement. Perhaps the Hittites did keep as many pigs, proportionally, as

the Early Iron Age inhabitants but they disposed of

them elsewhere in areas not yet excavated. Further

more, Hittite texts indicate use of pig fat or lard in

a range of ways, including as offerings to the gods (Hoffner 1995). Nevertheless, evidence from Kinet

H?y?k appears to support the B?y?kkaya shift, with a comparable increase in the proportion of pigs from

the Late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age there

(Ikram 2003: 289). The evidence from Iron Age pits at Ma?at also indicates a high degree of pig con

sumption, second only to cattle. Neonatal pig bones

at Ma?at suggest that they were being raised on site

(V. Ioannidou, personal communication, 2004). If pigs were an important part of the Late Bronze

Age Kaska economy, as the epithet "swineherds"

may suggest (contra see von Sch?ler 1965: 77), it

tells us something about their economy and life

style. Pigs are not enormously mobile animals. They thrive in damp forested regions, as commonly found

throughout the Pontic zone, but do not generally take

to seasonal transhumance. Their husbandry by the

Kaska, if a fundamental element of their subsistence,

suggests that Kaska peoples were largely sedentary and did not engage in wholesale migratory move

ments. At the same time, there is no reason to sup

pose that elements of the Kaska population did not

follow the yayla pattern of high summer pastures for sheep and goat so well attested in the Pontic re

gion today and historically. Hittite texts also show

that Kaska groups were granted special grazing rights when submitting to Hittite control (von Sch?ler 1965:

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

58 GLATZ AND MATTHEWS BASOR 339

33). It is rather notable that centuries later, during the

Byzantine Empire, Paphlagonia was renowned for its

high-quality bacon and its local inhabitants relegated from Hittite "swineherds" to Byzantine "pigs' arses"

(Magdalino 1998: 141-42). The second element of the Late Bronze Age

Early Iron Age faunal shift at Hattusa is the intro

duction of an apparently new practice: the eating of

equids. The evidence for this practice at Early Iron

Age Hattusa takes the form of cut-marks on bones

of horses, mules, and donkeys (von den Driesch and

P?llath 2003: 297). There is no evidence?textual or

archaeological, from Hattusa or elsewhere?for a

Hittite pursuit of this practice, although equid bones of Middle Bronze Age date from Acemh?y?k do

indicate deliberate butchery of equids (Nicola and Glew 1999: 108). For the Hittites, like the English in modern times, the horse appears to have been a

high-status animal with associations of social and

military standing, including its use in cavalry and

chariot contexts (Beal 1992: 133-37). Surprisingly, human sexual relations with horses and mules were

permitted, while being severely punished, by death, if with pigs, dogs, or sheep (Bryce 2002: 48). With

the deflation of this value system at the fall of the

Hittite Empire, the introduction of horse-eating may indicate an incursion of newcomers with a different

value system, the adoption of new values by surviv

ing elements of the preexisting population (some of whom apparently continued to make Hittite-style pots at the same time?see Schoop 2003: 172), or a

combination of both of these. In any case, there is

sufficient reason here to specify the culturally spe cific practice of horse-eating as a possible Kaska trait.

Good supporting evidence comes from an analysis of

the animal bones from Iron Age pits at Ma?at, where

clear butchery marks on horse bones indicate their

consumption (V. Ioannidou, personal communication,

2004). The third aspect of the Late Bronze Age-Early

Iron Age faunal shift at Hattusa noted by Von den

Driesch and P?llath is a reduction in the size of

both sheep and cattle, a feature also notable across

the same chronological span at the site of Kaman

Kaleh?y?k (Hongo 2003: 265). The authors also note

that evidence of stress traumas on cattle bones from

Early Iron Age levels at Hattusa suggests that the ani

mals were being worked harder and were less well

tended than in the Late Bronze Age (von den Driesch and P?llath 2003: 299). With regard to cattle, there

is an alternative interpretation of the two attributes,

reduction in size and increased stress traumas. A

steadily growing body of evidence, principally in the form of figurines, suggests that zebu, or humped cattle, were of increased importance in the Near East

from the late second millennium B.c. onward, per

haps in association with an episode of climatic dry ing (Matthews 2002). Late Bronze Age evidence for zebu in Anatolia is relatively scant, but a collec tion of small clay figurines from Geven Gedigi, a

shrine nearby Ku?akli-Sarissa, is associated with

pottery of Iron Age and perhaps Late Bronze Age date (Miller 1999). Zebu cattle are slightly smaller and more gracile than their non-humped or taurine cousins. In archaeological collections of faunal re

mains, it is extremely difficult to distinguish zebu

bones from taurine cattle bones. High-probability identification of zebu requires recovery of intact

thoracic vertebrae with their distinctive bifurcated

spinous processes (Epstein 1971: 198; Matthews 2002: fig. 5). Other bones of zebu closely resemble

those of taurine cattle but are smaller. Without posi tive identification of the relevant vertebrae at Hat

tusa, we cannot be sure that zebu were present there

in the Early Iron Age, but there remains the possi

bility that what is seen as a reduction in cattle size

from Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age is in fact a

replacement of taurine by zebu cattle, their gracile skeletons more prone to stress trauma in the exercise

of hard labor.

With regard to linen, the Hittite description of the Kaska as "weavers of linen" is likely to be signifi cant. The history of flax cultivation in Anatolia is

long, reaching back into the Neolithic period (Ertug 2000). Linen production is one of many uses to which the ?ax/Linum plant may be put, others including the extraction of linseed oil from flax seeds for cooking, lighting, and lubrication of wooden-wheeled carts.

Linseed oil and flax seeds are also widely attested as elements in modern folk medicine, and the residue from oil extraction may be used as animal fodder,

particularly for draft animals (Ertug 2000: 171). Pro

duction of linseed oil by villagers in Turkey ceased as recently as 20-25 years ago, the end of a millen

nia-long tradition (Ertug 2000: 174). Flax is found at

Ku?akh-Sarissa but has not been recovered at Hat tusa (Riehl and Nesbitt 2003: 301) and generally ap pears to be less common at Late Bronze Age and

Iron Age sites than in earlier prehistory, hinting at

its increasing substitution by olive and sesame oils

(Riehl and Nesbitt 2003: 306-7). Studies of names

for assorted oils in Hittite texts suggest that linseed

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2005 ANTHROPOLOGY OF A FRONTIER ZONE 59

oil may not have been significant in Hittite cuisine

and lighting, other oils and fats taking these roles

(G?terbock 1968; Hoffner 1995). Archaeobotanical studies at ?kiztepe, on the Black

Sea coast, indicate the cultivation of flax throughout the site's occupation, from the Chalcolithic to the

end of the Middle Bronze Age (Van Zeist 2003). Van

Zeist also points to a clear distinction between the

?kiztepe botanical evidence and that from contem

porary Early Bronze Age sites in north Syria, where

flax disappears from the archaeobotanical record after

a long representation from the Neolithic to the end of

the Ubaid period (Van Zeist 2003: 556). It may be

that the apparent cessation of flax cultivation at these

north Syrian sites at the start of the Late Chalcolithic, ca. 4000 b.c., correlates with a shift to wool and ol

ive production at the expense of linen and linseed

oil. In the case of rural Anatolia, the use of flax per sisted and may have become a sufficiently significant

distinguishing characteristic to be commented upon in one of the few epithets given by the Hittites to the

Kaska. Thus, differing social attitudes?conceivably rooted in an urban-rural opposition of wool/linen, olive oil/linseed oil?may have underlain the Hit

tites' characterization of the Kaska as "swineherds

and weavers of linen." It may be no coincidence

that up to modern times the Black Sea region has

been especially noted for its linen production (Ertug 2000: 176).

Apart from linen/flax, we have little idea of what

crops were grown by the Kaska. Hittite texts do not

say much even about their own crops, and archaeo

botanical investigation in Late Bronze Age Anatolia

is relatively young (Nesbitt 2002). When in control

of fertile plains in the border zone, the Hittites chan

neled agricultural produce into providing food for

troops, fodder for their animals, and cultic offerings to their deities. Kaska lands under Hittite control,

however temporarily, would also be expected to pay

agricultural tribute to Hittite temples, as the Prayer of Arnuwanda and Asmunikkal makes clear: "the

territories which were under obligation to present to

you, the gods of heaven, sacrificial loaves, libations

and tribute . . ." (Goetze in Pritchard 1969: 399). These scattered fragments of evidence allow us to

build a tentative picture of the Kaska of the Late

Bronze Age as a mobile highland people, growing an

array of crops in the fertile valleys and plains of their

land, raising cattle, sheep, goat, and pigs, and mov

ing their animals according to long-established sea

sonal patterns (see also Yakar 1980; 2000: 283-302).

Their architecture is likely to have comprised ele

ments of wood, mud-brick, and undressed stone, as

today in the region (fig. 6), and their settlements

were small and shifting. They may have used hand

made pottery and certainly would have made exten

sive use of wood and basketry for their containers.

They may have been distinguished from the Hittites

by a practice of using linen and linseed oil as against wool and olive oil. Above all, the Kaska have re

mained difficult to detect archaeologically.

THE NATURE OF HITTITE-KASKA

RELATIONS IN THE LIGHT OF

ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESULTS FROM

PROJECT PAPHLAGONIA

We have attempted to demonstrate that the rela

tionship between the Hittites and Kaska can best be

characterized as a complex, shifting web of interac

tions, maintained as a delicate balance over a period of several centuries. While the texts reveal the Hit

tites' desire to pacify and control a vulnerable fron

tier region, they also show how much flexibility was

exercised in their approach to the Kaska problem,

including being willing to identify "friendly" Kaska

elements, to recruit forces and labor from Kaska

tribes, and to make treaties with the enemy, in addi

tion to the well-tried military solutions. How might the archaeology of Paphlagonia in the Late Bronze

Age be brought to bear on this complex scenario?

This is not the place for a detailed and full presen tation of the Late Bronze Age material from the

Paphlagonia survey, but it may be useful to provide a summary of key attributes.

During the conduct of Project Paphlagonia, about

30 Late Bronze Age sites were detected, identified

by the presence of Hittite pottery on their surfaces

(fig. 7). In calling this pottery "Hittite," there is an

assumption that pottery similar to that found at Hat

tusa and other "Hittite" sites is likely to be Hittite, but it is possible that such pottery was made or used

by non-Hittite groups, including the Kaska. We still

know of no material culture items that can be col

lected from the surfaces of sites and identified as

exclusively Kaska, a situation that will remain until a Kaska site is excavated. We have referred above to

hints from Hattusa that a tradition of handmade pot

tery may have survived alongside the wheel-made

assemblages of the Late Bronze Age, and one day it

may prove possible to associate such material with

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

60 GLATZ AND MATTHEWS BASOR 339

>"? iV'-v*.

Fig. 6. Contemporary architecture in Paphlagonia.

a Kaska presence. There is also the possibility of a

rapid fluctuation of Hittites and Kaska living at the same site, with the ebb and flow of military action and treaty agreement, whereby a blurring occurs in

pottery and other aspects of material culture, as pre dicted in the Lightfoot and Martinez (1995) model

outlined above.

As regards chronology, there is a new willing ness in recent studies to accept that there are prob lems in the dating of Hittite ceramics, along with an

increased suspicion of previously accepted wisdom on the intricacies of Hittite chronology reliant on ce

ramic sequences. A new skepticism toward the glib association of scant historical records to excavated

"events," such as destruction levels, is rooted in a

healthy doubt and a determination to define and es

tablish "an archaeological chronology of Hittite culture" (Schoop 2003: 168, italics in original). The Late Bronze Age Paphlagonia pattern shows an in crease in density through the second millennium, with an increase of late Hittite over early Hittite

sites, a trend that supports a picture of increased Hit tite concern with controlling this frontier toward the end of the empire, as historically attested.

The newly located Late Bronze Age sites in Paph lagonia show attributes that strongly affirm the fron tier nature of the region. They are medium to large settlements, with no representation of sites that might be interpreted as small villages, hamlets, or isolated farmsteads. They are strategically located, normally on natural prominences at significant points in the

landscape, such as narrow passes or natural cross

roads, evincing a desire to control movement. Sites are located with ready access to fresh water, in the form of springs or streams, and to arable land, ensur

ing an ability to provide adequate supplies for the in

habitants, a garrison, and perhaps an army marching through, as mentioned above. Many of these sites have surviving traces of substantial fortifications as

well as ramps for the access of horses and perhaps chariots (fig. 8). Some of these planned and fortified sites appear to replace older traditional mounds, most

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2005 ANTHROPOLOGY OF A FRONTIER ZONE 61

Fig. 7. Distribution of Late Bronze Age sites in Paphlagonia survey region.

I?I w*ir

Fig. 8. Fortified Hittite site at Dumanli.

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

62 GLATZ AND MATTHEWS BASOR 339

??&'p4 'i.ii^-Sw^-.?f^??

Fig. 9. View of Salman West mound.

strikingly in the case of Salman West and East (fig. 9). The lack of small village sites in Paphlagonia con

trasts sharply with patterns attested in other Near

Eastern imperial impact scenarios, such as the expan sion of Assyria into southeast T\irkey, which is ac

companied by a massive increase in rural settlement

(Parker 2003). The Hittite-Kaska frontier zone was

never peaceable enough for such an expansion of un

protected settlement, nor for an attempt at intensified

rural settlement as a means of maximizing the tribu

tary agricultural production of the land.

The distribution of Late Bronze Age sites in Pa

phlagonia agrees well with a definition of the Devrez

?ay (probably Hittite Dahara, as identified by For

lanini 1977: 202-3) as a major frontier through the

Hittite period. For much of its course the Devrez runs

through severe gorges, and it would not be difficult

for either side to control movement across the river

from one zone to another, at the few points where a

traverse is possible. One small remote site at Eldi van is clearly positioned to act as a lookout site, with

clear visibility for many kilometers around and sherds

from large storage vessels.

A notable feature of the Late Bronze Age land

scape of Paphlagonia is the complete absence, as it so far seems, of Hittite carved rock monuments, such as occur in the core region and in areas to the south

of Hattusa. The landscape of Paphlagonia is dotted

with countless rock outcrops suitable for the carving of highly visible relief scenes, and their absence in

the region is not likely to be an accident but rather an

indication of the unsettled nature of this volatile bor

der zone. It is also likely that the Hittites realized that the Kaska were not likely to be a receptive audience

for their rock-cut propagandistic scenes.

The physical nature of the landscape was un

doubtedly significant in structuring the relationships between the Hittites and Kaska during their centu

ries-long drama. As mentioned above, Inner Paphlag onia straddles a truly transitional zone between the

Anatolian Plateau to the south and the Pontic Moun

tains to the north, with major routes to some extent

determined, at least encouraged, by the topography of the region. We should not underestimate the im

portance of the rivers of Inner Paphlagonia. They feature prominently in Hittite texts even if, with the

exception of Kizihrmak/Marassantiya and probably Devrez/Dahara, there are serious problems in equat

ing ancient and modern names. The study by Kimes,

Haselgrove, and Hodder (1982) of the distribution of

coins in Iron Age Britain established a strong rela

tionship between cultural boundaries and the pres ence of major rivers. It is clear that for much of the

second millennium b.c. the Devrez/Dahara formed a

natural and cultural boundary between the Hittites

and the Kaska, with territory around it a fortified

military zone, especially through the imperial pe riod. Within this frontier, a second and inner line

of Hittite defense was focused on the Kizihrmak/

Marassantiya, generally not a difficult river to cross

but still a clear boundary marker.

Another cultural feature of borders noted in the

study by Kimes, Haselgrove, and Hodder (1982: 126) is their repeated association with wastelands, barren

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2005 ANTHROPOLOGY OF A FRONTIER ZONE 63

territory often forcibly settled by outsiders. Again the

Kizilirmak/Marassantiya neatly fits this description,

especially for its passage through the Miocene salt

plateau that dominates this part of Inner Paphlagonia. The saline meadows of this region host only the most

salt-tolerant of plants, and provide little in the way of

sustenance for grazing animals and the people who

depend on them for food. And yet there are small

villages today strung along this barren terrain. They are inhabited principally by Kurdish villagers, settled

here during the 19th century a.D. by the Ottoman au

thorities. Similar settlements of peoples, sometimes

far from their homes, were made by the Hittite kings in their attempts to populate and control the other

wise barren wastelands that lay along much of this

frontier zone.

Finally, the extent to which the Kaska were in

volved in the final collapse of the Hittite Empire is

unknown, precisely because our written sources about

them cease at that very point. Assyrian references to

the Kaska as far east as the Upper Euphrates in the

early 11th century b.c. suggest that the Kaska had by then swept across the entirety of central and southern

Anatolia (Bryce 1998: 388). By that stage, the fron

tier zone of Inner Paphlagonia had dissipated, its for

tified and ramparted sites long abandoned and put to

the torch by the Kaska. In this respect we might call

them the silent victors of Late Bronze Age Anatolia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Project Paphlagonia field work was generously funded

by the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara, to whom

sincere thanks are extended. We also thank the Directorate

General of Monuments and Museums of the Republic of

Turkey for granting relevant permissions.

REFERENCES

Alp, S.

1991 Hethitische Briefe aus Masat-H?y?k. T?rk Tarin Kurumu, Series 6, no. 35. Ankara: T?rk

Tarih Kurumu.

Beal, R. H.

1992 The Organisation of the Hittite Military. Texte der Hethiter 20. Heidelberg: Winter.

Beckman, G.

1999 The City and the Country of Hatti. Pp. 161-69 in Landwirtschaft im alten Orient: Ausgew?hlte

Vortr?ge der XLI. Rencontre Assy ri?lo gique

Internationale, Berlin, 4.-8.7.1994, eds. H.

Klengel and J. Renger. Berliner Beitr?ge zum

Vorderen Orient 18. Berlin: Reimer.

2000 Hittite Chronology. Akkadica 119-120: 19-32.

Bilgen, A. N.

1999 Kastamonu Kimk Kazisi 1994-1995 Metal?rjik Buluntulan. Anadolu Arastirmalari 15: 269-93.

Bittel, K.

1970 Hattusha, the Capital of the Hittites. New

York: Oxford University.

Bryce, T. R.

1986- The Boundaries of Hatti and Hittite Border

1987 Policy. Tel Aviv 13-14: 85-102. 1998 The Kingdom of the Hittites. Oxford: Oxford

University.

2002 Life and Society in the Hittite World. Oxford: Oxford University.

Burney, C. A.

1956 Northern Anatolia before Classical Times. Anatolian Studies 6: 179-203.

CTH = Laroche, E.

1971 Catalogue des textes hittites. ?tudes et com

mentaires 75. Paris: Klincksieck.

De Atley, S. P., and Findlow, F. J.

1984 Exploring the Limits: Frontiers and Bound aries in Prehistory. BAR International Series

223. Oxford: B.A.R.

Din?ol, A. M., and Yakar, J.

1974 The Localization of Nerik Reconsidered. Belleten 37: 563-82.

Emre, K., and ?inaroglu, A.

1993 A Group of Metal Hittite Vessels from Kinik Kastamonu. Pp. 675-717 in Aspects of Art and

Iconography: Anatolia and Its Neighbors:

Studies in Honor of Nimet ?zg?c, eds. M. J.

Mellink, E. Porada, and T. ?zg?c. Ankara:

Turk Tarih Kurumu.

Epstein, H.

1971 Origin of the Domestic Animals of Africa. 2 vols. New York: Africana.

Ertug, F.

2000 Linseed Oil and Oil Mills in Central Turkey. Flax/Lmwra and Eruca, Important Oil Plants of

Anatolia. Anatolian Studies 50: 171-85.

Forlanini, M.

1977 L'Anatolia Nordoccidentale Nell'Impero Eteo. Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici 18: 197? 225.

Gates, M.-H.

1997 Archaeology in Turkey. American Journal of Archaeology 101: 241-305.

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

64 GLATZ AND MATTHEWS BASOR 339

Genz, H.

2003 The Early Iron Age in Central Anatolia. Pp. 179-91 in Identifying Changes: The Transition

from Bronze to Iron Ages in Anatolia and Its

Neighbouring Regions. Proceedings of the In

ternational Workshop, Istanbul, November 8

9, 2002, eds. B. Fischer, H. Genz, ?. Jean, and

K. K?roglu. Istanbul: Turk Eski?ag Bilimleri Enstit?s?.

Goetze, A.

1960 The Beginning of the Hittite Instructions for the Commander of the Border Guards. Journal

of Cuneiform Studies 14: 69-73.

Gorny, R. L.

1995 Hittite Imperialism and Anti-Imperial Resis tance as Viewed from Alishar H?y?k. Bulletin

of the American Schools of Oriental Research

299-300: 65-89.

Gurney, O. R.

1979 The Hittite Empire. Pp. 151-65 in Power and

Propaganda: A Symposium on Ancient Em

pires, ed. M. T. Larsen. Mesopotamia 7. Copen

hagen: Akademisk.

G?terbock, H. G.

1956 The Deeds of Suppiluliuma as Told by his Son, Mursili II. Journal of Cuneiform Studies 10:

41-68, 75-98, 107-30.

1968 Oil Plants in Hittite Anatolia. Journal of the American Oriental Society 88: 66-71.

Haas, V

1970 Der Kult von Nerik: Ein Beitrag zur hethiti schen Religionsgeschichte. Studia Pohl 4. Rome:

P?pstliches Bibelinstitut.

Hoffner, H. A., Jr.

1995 Oil in Hittite Texts. Biblical Archaeologist 58: 108-14.

2002 The Treatment and Long-Term Use of Persons

Captured in Battle according to the Ma?at Texts.

Pp. 61-72 m Recent Developments in Hittite Ar

chaeology and History: Papers in Memory of

Hans G. G?terbock, eds. K. A. Yener and H. A.

Hoffner Jr. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

Hongo, H.

2003 Continuity or Changes: Faunal Remains from

Stratum lid at Kaman-Kaleh?y?k. Pp. 257-69

in Identifying Changes: The Transition from Bronze to Iron Ages in Anatolia and Its Neigh

bouring Regions. Proceedings of the Interna

tional Workshop, Istanbul, November 8-9,

2002, eds. B. Fischer, H. Genz, E. Jean, and

K. K?roglu. Istanbul: Turk Eski?ag Bilimleri Enstit?s?.

Houwink ten Cate, P. H. J.

1979 Mursilis' Northwestern Campaigns?Addi

tional Fragments of his Comprehensive Annals

Concerning the Nerik Region. Pp. 157-67 in

Florilegium Anatolicum: M?langes offerts ?

Emmanuel Laroche. Paris: De Boccard.

1984 The History of Warfare According to Hittite Sources: The Annals of Hattusilis I (Part II).

Anatolica 11: 47-83.

Ikram, S.

2003 A Preliminary Study of Zooarchaeological Changes between the Bronze and Iron Ages at

Kinet H?y?k, Hatay. Pp. 283-94 in Identifying Changes: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

Ages in Anatolia and Its Neighbouring Regions.

Proceedings of the International Workshop,

Istanbul, November 8-9, 2002, eds. B. Fischer,

H. Genz, E. Jean, and K. K?roglu. Istanbul:

Turk Eski?ag Bilimleri Enstit?s?.

Kimes, T.; Haselgrove, C; and Hodder, I.

1982 A Method for the Identification of the Location of Regional Cultural Boundaries. Journal of

Anthropological Archaeology 1:113-31.

Kiengel, H.

1999 Geschichte des Hethitischen Reiches. Hand

buch der Orientalistik. Erste Abteilung. Der Nahe und der Mittlere Osten 34. Leiden: Brill.

KUB XIII = Keilschrifturkunden aus Boghazk?i 1925 Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorder

asiatische Abteilung.

Lightfoot, K. G., and Martinez, A.

1995 Frontiers and Boundaries in Archaeological Perspective. Annual Review of Anthropology

24: 471-92.

Macqueen, J. G.

1980 Nerik and Its "Weather-God." Anatolian Stud

ies 30: 179-87.

Magdalino, P.

1998 Paphlagonians in Byzantine High Society. Pp.

141-50 in Byzantine Asia Minor, 6th-12th

Centuries. Speros Basil Vryonis Center for the

Study of Hellenism 27. Athens: Institute for

Byzantine Research.

Matthews, R.

2000 Time with the Past in Paphlagonia. Pp. 1013

27 in Proceedings of the First International

Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient

Near East, Rome May 18th-23rd 1998, eds. P.

Matthiae, A. Enea, L. Peyronel, and F. Pinnock.

2 vols. Rome: Uni ver sita degli Studi di Roma "La Sapienza."

2002 Zebu: Harbingers of Doom in Bronze Age Western Asia? Antiquity 76: 438-46.

Matthews, R.; Pollard, T.; and Ramage, M.

1998 Project Paphlagonia: Regional Survey in North ern Anatolia. Pp. 195-206 in Ancient Anatolia:

Fifty Years' Work by the British Institute of Ar

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2005 ANTHROPOLOGY OF A FRONTIER ZONE 65

chaeology at Ankara, ed. R. Matthews. London:

British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara.

Miller, J.

1999 A Collection of Zoomorphic Terracotta from Geven Gedigi. Mitteilungen der Deutschen

Orient-Gesellschaft 131: 91-96.

Nesbitt, M.

2002 Plants and People in Ancient Anatolia. Pp. 5

18 in Across the Anatolian Plateau: Read

ings in the Archaeology of Ancient Turkey,

?d. D. C. Hopkins. Annual of the American

Schools of Oriental Research 57. Boston:

American Schools of Oriental Research.

Nicola, J., and Glew, C.

1999 Assyrian Colony Period Fauna from Acem

h?y?k Level III: A Preliminary Analysis. Pp. 93-148 in Essays on Ancient Anatolia, ed. T.

Mikasa. Bulletin of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan 11. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

?zsait, M.

2003 Les c?ramiques du fer ancien dans les r?gion

d'Amasya et de Samsun. Pp. 199-212 in Iden

tifying Changes: The Transition from Bronze to

Iron Ages in Anatolia and Its Neighbouring

Regions. Proceedings of the International

Workshop, Istanbul, November 8-9, 2002, eds.

B. Fischer, H. Genz, ?. Jean, and K. K?roglu.

Istanbul: Turk Eski?ag Bilimleri Enstit?s?.

Parker, B. J.

2003 Archaeological Manifestations of Empire: Assyria's Imprint on Southeastern Anatolia.

American Journal of Archaeology 107: 525-57.

Pritchard, J. B.

1969 Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the

Old Testament. 3rd ed. Princeton: Princeton

University.

Riehl, S., and Nesbitt, M.

2003 Crops and Cultivation in the Iron Age Near East: Change or Continuity? Pp. 301-12 in

Identifying Changes: The Transition from Bronze to Iron Ages in Anatolia and Its Neigh

bouring Regions. Proceedings of the Interna

tional Workshop, Istanbul, November 8-9,

2002, eds. B. Fischer, H. Genz, ?. Jean, and

K. K?roglu. Istanbul: Turk Eski?ag Bilimleri Enstit?s?.

Schoop, U.-D.

2003 Pottery Traditions of the Later Hittite Empire: Problems of Definition. Pp. 167-78 in Identi

fying Changes: The Transition from Bronze to

Iron Ages in Anatolia and Its Neighbouring

Regions. Proceedings of the International

Workshop, Istanbul, November 8-9, 2002, eds.

B. Fischer, H. Genz, ?. Jean, and K. K?roglu.

Istanbul: Turk Eski?ag Bilimleri Enstit?s?.

Seeher, J.

1997 Die Ausgrabungen in Bogazk?y-Hattusa 1996.

Arch?ologischer Anzeiger: 317-41.

Singer, I.

1984 The AGRIG in the Hittite Texts. Anatolian Studies 34: 97-127.

?nal, A.

1998 Hittite and Hurrian Cuneiform Tablets from Or

tak?y (?orum), Central Turkey. With Two Ex

cursuses on the "Man of the Storm God" and a

Full Edition ofKBo 23.27. Istanbul: Simurg. Van De Mieroop, M.

2000 Sargon of Agade and His Successors in Anato lia. Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici 42:133-59.

Van Zeist, W.

2003 An Archaeobotanical Study of Ikiztepe, North ern Turkey. Pp. 547-81 in From Village to Cit

ies: Early Villages in the Near East: Studies Presented to Ufuk Esin, eds. M. ?zdogan, H.

Hauptmann, and N. Bangelen. 2 vols. Istanbul:

Arkeoloji ve Sanat.

von den Driesch, A., and P?llath, N.

2003 Changes from Late Bronze Age to Early Iron

Age Animal Husbandry as Reflected in the

Faunal Remains from B?y?kkaya/Bogazk?y Hattusa. Pp. 295-99 in Identifying Changes:

The Transition from Bronze to Iron Ages in Ana

tolia and Its Neighbouring Regions. Proceed

ings of the International Workshop, Istanbul,

November 8-9, 2002, eds. B. Fischer, H. Genz,

?. Jean, and K. K?roglu. Istanbul: Turk Eski?ag

Bilimleri Enstit?s?. von Schuler, E.

1965 Die Kask?er: Ein Beitrag zur Ethnographie des alten Kleinasien. Untersuchungen zur Assyri

ologie und vorderasiatischen Arch?ologie 3.

Berlin: de Gruyter.

Yakar, J.

1980 Recent Contributions to the Historical Geogra

phy of the Hittite Empire. Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 112: 75-94.

2000 Ethnoarchaeology of Anatolia: Rural Socio

Economy in the Bronze and Iron Ages. Mono

graph Series 17. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, Institute of Archaeology.

Yakar, J., and Din?ol, A. M.

1974 Remarks on the Historical Geography of North

Central Anatolia during the Pre-Hittite and Hit

tite Periods. Tel Aviv 1: 85-99.

Yildinm, T., and Sipahi, T

2004 2002 Yih ?orum ve ?ankin ?lleri Y?zey Ara?tirmalan. Arastirma Sonu?lari Toplantisi 21: 305-14.

This content downloaded from 78.111.165.165 on Tue, 30 Apr 2013 01:27:51 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

![-- (Arabic) · Web view3.5وينبغي للدول الأعضاء أن تبذل كل مساعيها [، بالتشاور مع الجماعات الأصلية والمحلية،] من](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5e551967d822693a7f6e7126/-arabic-web-view-35-f.jpg)